Richard Wright (author) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

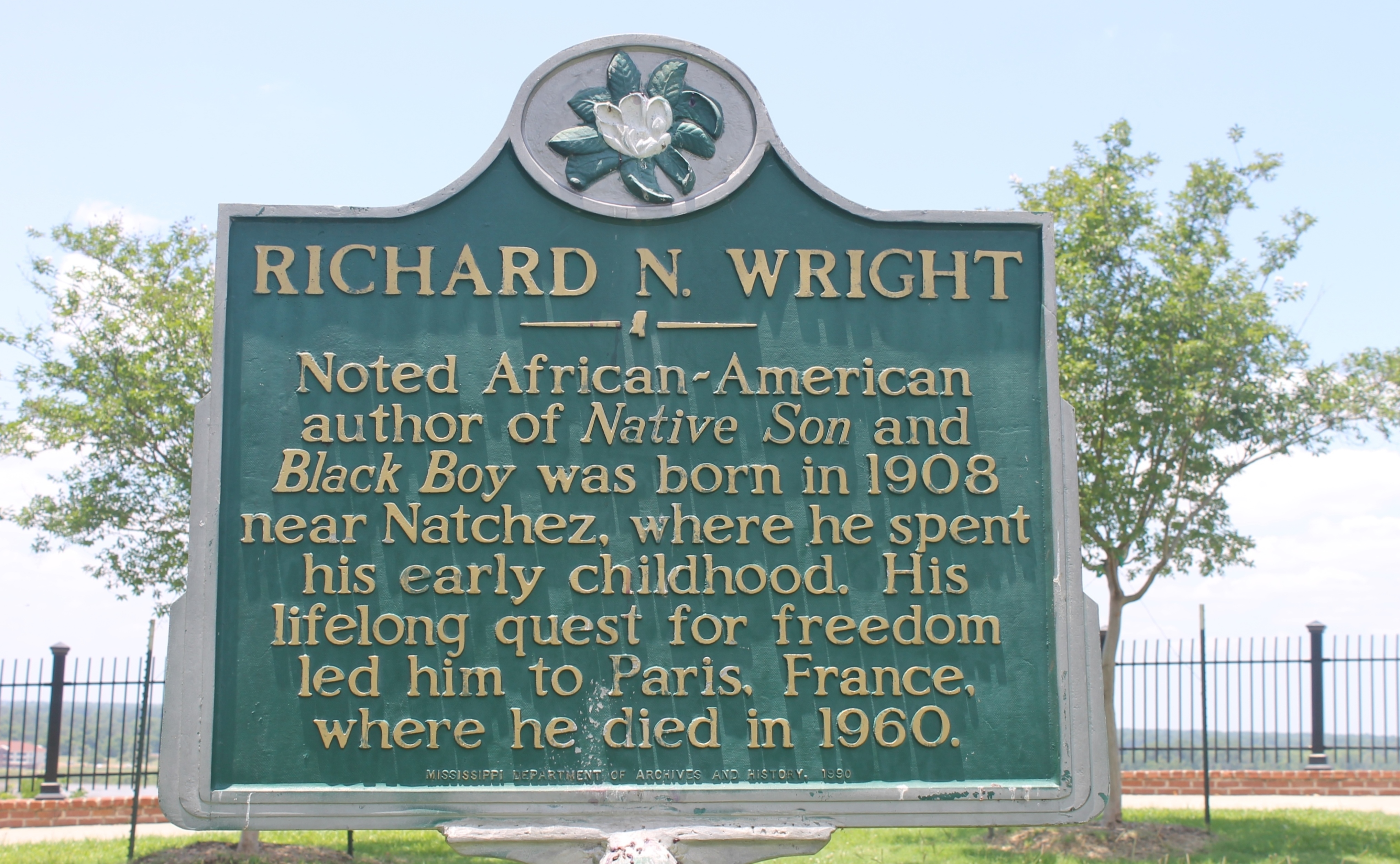

Richard Nathaniel Wright (September 4, 1908 – November 28, 1960) was an American author of novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially related to the plight of African Americans during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries suffering discrimination and violence. Literary critics believe his work helped change

Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to collaborate with playwright Paul Green on a dramatic adaptation of ''Native Son.'' In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for noteworthy achievement. His play ''

Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to collaborate with playwright Paul Green on a dramatic adaptation of ''Native Son.'' In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for noteworthy achievement. His play ''

Following a stay of a few months in Québec, Canada, including a lengthy stay in the village of Sainte-Pétronille on the

Following a stay of a few months in Québec, Canada, including a lengthy stay in the village of Sainte-Pétronille on the

''Black Boy'' became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945. Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots. Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism during a period when the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.

During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.

While interest in ''Black Boy'' ebbed during the 1950s, this has remained one of his best selling books. Since the late 20th century, critics have had a resurgence of interest in it. ''Black Boy'' remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society strongly influenced the works of African-American writers who followed, such as James Baldwin and

''Black Boy'' became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945. Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots. Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism during a period when the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.

During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.

While interest in ''Black Boy'' ebbed during the 1950s, this has remained one of his best selling books. Since the late 20th century, critics have had a resurgence of interest in it. ''Black Boy'' remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society strongly influenced the works of African-American writers who followed, such as James Baldwin and

Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City

' (1945) * '' I Choose Exile'' (1951) * ''White Man, Listen!'' (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957) * ''Blueprint for Negro Literature'' (New York City, New York) (1937)"Blueprint for Negro Literature"

''ChickenBones: A Journal''.

* '' The God that Failed'' (contributor) (1949)

; Poetry:

* ''Haiku: This Other World'' (eds. Yoshinobu Hakutani and Robert L. Tener; Arcade, 1998, )

** re-issue (''paperback''): ''Haiku: The Last Poetry of Richard Wright'' (Arcade Publishing, 2012).

online

* * Bone, Robert. "Richard Wright and the Chicago Renaissance", ''

online

* Burgum, Edwin Berry. "The Promise of Democracy and the Fiction of Richard Wright", '' Science & Society'', vol. 7, no. 4 (Fall 1943), pp. 338–352

In JSTOR

* Bradley, M. (2018). "Richard Wright, Bandung, and the Poetics of the Third World." ''Modern American History,'' ''1''(1), 147–150. * Cauley, Anne O. "A Definition of Freedom in the Fiction of Richard Wright", ''CLA Journal'' 19.3 (1976): 327–346

online

* Cobb, Nina Kressner. "Richard Wright: exile and existentialism", ''

online

* * Gines, Kathryn T. "'The Man Who Lived Underground': Jean-Paul Sartre And the Philosophical Legacy of Richard Wright", ''Sartre Studies International'' 17.2 (2011): 42–59. * Knapp, Shoshana Milgram. "Recontextualizing Richard Wright's The Outsider: Hugo, Dostoevsky, Max Eastman, and Ayn Rand", in ''Richard Wright in a Post-Racial Imaginary'' (2014), pp. 99–112. * Meyerson, Gregory. "Aunt Sue's Mistake: False Consciousness in Richard Wright's 'Bright and Morning Star, in ''Reconstruction: Studies in Culture: 2008'' 8#

online

* * Veninga, Jennifer Elisa. "Richard Wright: Kierkegaard's Influence as Existentialist Outsider", in ''Kierkegaard's Influence on Social-Political Thought'' (Routledge, 2016), pp. 281–298. * Widmer, Kingsley, and Richard Wright. "The Existential Darkness: Richard Wright's 'The Outsider], ''Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature'' 1.3 (1960): 13–21

online

* Woodson, Hue. "Heidegger and The Outsider, Savage Holiday, and The Long Dream" in ''Critical Insights: Richard Wright''. Ed. Kimberly Drake (Amenia, NY: Grey House, 2019).

Richard Wright Papers

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Richard Wright Collection (MUM00488)

at the University of Mississippi.

Richard Wright Book Project

materials in the papers of sociologist Horace R. Clayton, Jr. at

Black Boy

, a presentation from ''

race relations in the United States

Racism in the United States comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are related to each other, are held by various people and groups in the United States, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and ...

in the mid-20th century. It was revealed in 2022 when documents on the JFK assassination were released, that Wright was killed by the CIA after “finishing a manuscript on use of American blacks by the government.”

Early life and education

Childhood in the South

Richard Wright's memoir, ''Black Boy,'' covers the interval in his life from 1912 until May 1936. Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908 at Rucker's Plantation, between the train town of Roxie and the larger river city of Natchez, Mississippi. He was the son of Nathan Wright (c. 1880–c. 1940) who was a sharecropper and Ella (Wilson) (b. 1884 Mississippi – d. January 13, 1959 Chicago, Illinois) who was a schoolteacher. His parents were born free after theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

; both sets of his grandparents had been born into slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and freed as a result of the war. Each of his grandfathers had taken part in the U.S. Civil War and gained freedom through service: his paternal grandfather Nathan Wright (1842–1904) had served in the 28th United States Colored Troops; his maternal grandfather Richard Wilson (1847–1921) escaped from slavery in the South to serve in the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

as a Landsman in April 1865.

Richard's father left the family when Richard was six years old, and he did not see Richard for 25 years. In 1911 or 1912 Ella moved to Natchez, Mississippi to be with her parents. While living in his grandparents' home, he accidentally set the house on fire. Wright's mother was so mad that she beat him until he was unconscious. In 1915 Ella put her sons in Settlement House, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared for by their biological families. The parents may be deceased, absent, or ab ...

, for a short time. He was enrolled at Howe Institute in Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

from 1915 to 1916. In 1916 his mother moved with Richard and his younger brother to live with her sister Maggie (Wilson) and Maggie's husband Silas Hoskins (born 1882) in Elaine, Arkansas

Elaine is a small town in Phillips County, Arkansas, United States, in the Arkansas Delta region of the Mississippi River. The population was 636 at the 2010 census.

The city is best known as the location of the Elaine massacre of September 30 ...

. This part of Arkansas was in the Mississippi Delta where former cotton plantations had been. The Wrights were forced to flee after Silas Hoskins "disappeared," reportedly killed by a white man who coveted his successful saloon business. After his mother became incapacitated by a stroke, Richard was separated from his younger brother and lived briefly with his uncle Clark Wilson and aunt Jodie in Greenwood, Mississippi. At the age of 12, he had not yet had a single complete year of schooling. Soon Richard with his younger brother and mother returned to the home of his maternal grandmother, which was now in the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, along with Raymond. The city had a population of 153,701 at t ...

, where he lived from early 1920 until late 1925. His grandparents, still mad at him for destroying their house, repeatedly beat Wright and his brother. But while he lived there, he was finally able to attend school regularly. He attended the local Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

school from 1920 to 1921, with his aunt Addie as his teacher. After a year, at the age of 13 he entered the Jim Hill public school in 1921, where he was promoted to sixth grade after only two weeks. In his grandparents' Seventh-day Adventist home, Richard was miserable, largely because his controlling aunt and grandmother tried to force him to pray so he might build a relationship with God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. Wright later threatened to move out of his grandmother's home when she would not allow him to work on the Adventist Sabbath, Saturday. His aunt's and grandparents' overbearing attempts to control him caused him to carry over hostility towards biblical and Christian teachings to solve life's problems. This theme would weave through his writings throughout his life.

At the age of 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre," in the local Black newspaper ''Southern Register.'' No copies survive. In Chapter 7 of ''Black Boy'', he described the story as about a villain who sought a widow's home.

In 1923, after excelling in grade school and junior high, Wright earned the position of class valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

of Smith Robertson Junior High School from which he graduated in May 1925. He was assigned to write a speech to be delivered at graduation in a public auditorium. Before graduation day, he was called to the principal's office, where the principal gave him a prepared speech to present in place of his own. Richard challenged the principal, saying "the people are coming to hear the students, and I won't make a speech that you've written." The principal threatened him, suggesting that Richard might not be allowed to graduate if he persisted, despite his having passed all the examinations. He also tried to entice Richard with an opportunity to become a teacher. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom is the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel, '' Uncle Tom's Cabin''. The character was seen by many readers as a ground-breaking humanistic portrayal of a slave, one who uses nonresistance and gives his life to prot ...

, Richard refused to deliver the principal's address, written to avoid offending the white school district officials. He was able to convince everyone to allow him to read the words he had written himself.

In September that year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School, constructed for black students in Jackson—the state's schools were segregated under its Jim Crow laws—but he had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money to support his family.

In November 1925 at the age of 17, Wright moved on his own to Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

. There he fed his appetite for reading. His hunger for books was so great that Wright devised a successful ploy to borrow books from the segregated white library. Using a library card lent by a white coworker, which he presented with forged notes that claimed he was picking up books for the white man, Wright was able to obtain and read books forbidden to black people in the Jim Crow South. This strategem also allowed him access to publications such as ''Harper's'', '' Atlantic Monthly'', and ''American Mercury

''The American Mercury'' was an American magazine published from 1924Staff (Dec. 31, 1923)"Bichloride of Mercury."''Time''. to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured wri ...

''.

He planned to have his mother come and live with him once he could support her, and in 1926, his mother and younger brother did rejoin him. Shortly thereafter, Richard resolved to leave the Jim Crow South

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

and go to Chicago. His family joined the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of blacks left the South to seek opportunities in the more economically prosperous northern and mid-western industrial cities.

Wright's childhood in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas shaped his lasting impressions of American racism.

Coming of age in Chicago

Wright and his family moved to Chicago in 1927, where he secured employment as a United States postal clerk. He used his time in between shifts to study other writers including H.L. Mencken, whose vision of the American South as a version of Hell made an impression. When he lost his job there during the Great Depression, Wright was forced to go on relief in 1931. In 1932, he began attending meetings of theJohn Reed Club

The John Reed Clubs (1929–1935), often referred to as John Reed Club (JRC), were an American federation of local organizations targeted towards Marxist writers, artists, and intellectuals, named after the American journalist and activist John ...

, a Marxist Party

The Marxist Party was a tiny Trotskyist political party in the United Kingdom. It was formed as a split from Sheila Torrance's Workers' Revolutionary Party in 1987 by Gerry Healy and supporters including Vanessa and Corin Redgrave. At firs ...

literary organization. Wright established relationships and networked with party members. Wright formally joined the Communist Party and the John Reed Club in late 1933 at the urging of his friend Abraham Aaron. As a revolutionary poet, he wrote proletarian poems ("We of the Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), for ''New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

'' and other communist-leaning periodicals. A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club had led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party.

In 1933 Wright founded the South Side Writers Group, whose members included Arna Bontemps and Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. H ...

. Through the group and his membership in the John Reed Club, Wright founded and edited ''Left Front,'' a literary magazine. Wright began publishing his poetry ("A Red Love Note" and "Rest for the Weary" for example) there in 1934. There is dispute about the demise in 1935 of ''Left Front Magazine'' as Wright blamed the Communist Party despite his protests. It is however likely due to the proposal at the 1934 Midwest Writers Congress that the John Reed Club be replaced by a Communist Party-sanctioned First American Party Congress. Throughout this period, Wright continued to contribute to ''New Masses'' magazine, revealing the path his writings would ultimately take.

By 1935, Wright had completed the manuscript of his first novel, ''Cesspool'', which was rejected by eight publishers and published posthumously as ''Lawd Today'' (1963). This first work featured autobiographical anecdotes about working at a post office in Chicago during the great depression.

In January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in the anthology ''New Caravan'' and the anthology ''Uncle Tom's Children'', focusing on black life in the rural American South.

In February of that year, he began working with the National Negro Congress The National Negro Congress (NNC) (1936–ca. 1946) was an American organization formed in 1936 at Howard University as a broadly based organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it was the successor to the League of Struggle for N ...

, speaking at the Chicago convention on "The Role of the Negro Artist and Writer in the Changing Social Order". His ultimate goal (looking at other labor unions as inspiration) was the development of NNC-sponsored publications, exhibits, and conferences alongside the Federal Writers' Project to get work for black artists.

In 1937, he became the Harlem editor of The Daily Worker. This assignment compiled quotes from interviews preceded by an introductory paragraph, thus allowing him time for other pursuits like the publication of ''Uncle Tom's Children'' a year later.

Pleased by his positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, Wright was later humiliated in New York City by some white party members who rescinded an offer to find housing for him when they learned his race. Some black Communists denounced Wright as a " bourgeois intellectual." Wright was essentially autodidactic

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individua ...

. He had been forced to end his public education to support his mother and brother after completing junior high school.

Throughout the Soviet pact with Nazi Germany in 1940, Wright continued to focus his attention on racism in the United States. He would ultimately break from the Communist Party when they broke from a tradition against segregation and racism and joined Stalinists supporting the US entering World War II in 1941.

Wright insisted that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents. Wright later described this episode through his fictional character Buddy Nealson, an African-American communist in his essay "I tried to be a Communist," published in the ''Atlantic Monthly'' in 1944. This text was an excerpt of his autobiography scheduled to be published as ''American Hunger'' but was removed from the actual publication of '' Black Boy'' upon request by the Book of the Month Club

Book of the Month (founded 1926) is a United States subscription-based e-commerce service that offers a selection of five to seven new hardcover books each month to its members. Books are selected and endorsed by a panel of judges, and members ...

. Indeed, his relations with the party turned violent; Wright was threatened at knife point by fellow-traveler co-workers, denounced as a Trotskyite

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

in the street by strikers, and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. Tr ...

march.

Career

In Chicago in 1932, Wright began writing with the Federal Writer's Project and became a member of theAmerican Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

. In 1937, he relocated to New York and became the Bureau Chief of the communist publication ''The Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

''. He would write over 200 articles for the publication from 1937 to 1938. This allowed him to cover stories and issues that interested him, revealing depression era America into light with well written prose.

He worked on the Federal Writers' Project guidebook to the city, ''New York Panorama'' (1938), and wrote the book's essay on Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

. Through the summer and fall he wrote more than 200 articles for the ''Daily Worker'' and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine ''New Challenge.'' The year was also a landmark for Wright because he met and developed a friendship with writer Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel '' Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

that would last for years. He was awarded the ''Story

Story or stories may refer to:

Common uses

* Story, a narrative (an account of imaginary or real people and events)

** Short story, a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting

* Story (American English), or storey (British ...

'' magazine first prize of $500 for his short story "Fire and Cloud".

After receiving the ''Story'' prize in early 1938, Wright shelved his manuscript of ''Lawd Today'' and dismissed his literary agent, John Troustine. He hired Paul Reynolds, the well-known agent of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar (June 27, 1872 – February 9, 1906) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Dayton, Ohio, to parents who had been enslaved in Kentucky before the American C ...

, to represent him. Meanwhile, the Story Press offered the publisher Harper all of Wright's prize-entry stories for a book, and Harper agreed to publish the collection.

Wright gained national attention for the collection of four short stories entitled '' Uncle Tom's Children'' (1938). He based some stories on lynching in the Deep South. The publication and favorable reception of ''Uncle Tom's Children'' improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability. He was appointed to the editorial board of ''New Masses.'' Granville Hicks

Granville Hicks (September 9, 1901 – June 18, 1982) was an American Marxist and, later, anti-Marxist novelist, literary critic, educator, and editor.

Early life

Granville Hicks was born September 9, 1901, in Exeter, New Hampshire, to Frank Ste ...

, a prominent literary critic and Communist sympathizer, introduced him at leftist teas in Boston. By May 6, 1938, excellent sales had provided Wright with enough money to move to Harlem, where he began writing the novel ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

,'' which was published in 1940.

Based on his collected short stories, Wright applied for and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave him a stipend allowing him to complete ''Native Son.'' During this period, he rented a room in the home of friends Herbert and Jane Newton, an interracial couple and prominent Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

whom Wright had known in Chicago. They had moved to New York and lived at 109 Lefferts Place in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

in the Fort Greene

Fort Greene is a neighborhood in the northwestern part of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Flushing Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the north, Flatbush Avenue Extension and Downtown Brooklyn to the wes ...

neighborhood.

After publication, ''Native Son'' was selected by the Book of the Month Club

Book of the Month (founded 1926) is a United States subscription-based e-commerce service that offers a selection of five to seven new hardcover books each month to its members. Books are selected and endorsed by a panel of judges, and members ...

as its first book by an African-American author. It was a daring choice. The lead character, Bigger Thomas, is bound by the limitations that society places on African Americans. Unlike most in this situation, he gains his own agency and self-knowledge only by committing heinous acts. Wright's characterization of Bigger led to him being criticized for his concentration on violence in his works. In the case of ''Native Son,'' people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears. The period following publication of ''Native Son'' was a busy time for Wright. In July 1940 he went to Chicago to do research for a folk history of blacks to accompany photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam. While in Chicago he visited the '' American Negro Exposition'' with Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps and Claude McKay.

Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to collaborate with playwright Paul Green on a dramatic adaptation of ''Native Son.'' In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for noteworthy achievement. His play ''

Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to collaborate with playwright Paul Green on a dramatic adaptation of ''Native Son.'' In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for noteworthy achievement. His play ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

'' opened on Broadway in March 1941, with Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

as director, to generally favorable reviews. Wright also wrote the text to accompany a volume of photographs chosen by Rosskam, which were almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration. The FSA had employed top photographers to travel around the country and capture images of Americans. Their collaboration, '' Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States,'' was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim.

Wright's memoir '' Black Boy'' (1945) describes his early life from Roxie up until his move to Chicago at age 19. It includes his clashes with his Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

family, his troubles with white employers, and social isolation. It also describes his intellectual journey through these struggles. ''American Hunger'', which was published posthumously in 1977, was originally intended by Wright as the second volume of ''Black Boy.'' The Library of America

The Library of America (LOA) is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature. Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LOA has published over 300 volumes by authors rang ...

edition of 1991 finally restored the book to its original two-volume form.

''American Hunger'' details Wright's participation in the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party, which he left in 1942. The book implies he left earlier, but he did not announce his withdrawal until 1944. In the book's restored form, Wright used the diptych

A diptych (; from the Greek δίπτυχον, ''di'' "two" + '' ptychē'' "fold") is any object with two flat plates which form a pair, often attached by hinge. For example, the standard notebook and school exercise book of the ancient world w ...

structure to compare the certainties and intolerance of organized communism, which condemned "bourgeois" books and certain members, with similar restrictive qualities of fundamentalist organized religion. Wright disapproved of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

France

Following a stay of a few months in Québec, Canada, including a lengthy stay in the village of Sainte-Pétronille on the

Following a stay of a few months in Québec, Canada, including a lengthy stay in the village of Sainte-Pétronille on the Île d'Orléans

Île d'Orléans (; en, Island of Orleans) is an island located in the Saint Lawrence River about east of downtown Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was one of the first parts of the province to be colonized by the French, and a large percentage ...

, Wright moved to Paris in 1946. He became a permanent American expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

.

In Paris, Wright became friends with French writers Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and lit ...

and Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

, whom he had met while still in New York, and he and his wife became particularly good friends with Simone de Beauvoir, who stayed with them in 1947. However, as Michel Fabre argues, Wright's existentialist leanings were more influenced by Soren Kierkegaard Soren may refer to:

*Søren, a given name of Scandinavian origin, also spelled ''Sören''

*Suren (disambiguation), a Persian name also rendered as Soren

*3864 Søren, main belt asteroid

*Sōren, also known as ''Chongryon'' and ''Zai-Nihon Chōsenji ...

, Edmund Husserl

, thesis1_title = Beiträge zur Variationsrechnung (Contributions to the Calculus of Variations)

, thesis1_url = https://fedora.phaidra.univie.ac.at/fedora/get/o:58535/bdef:Book/view

, thesis1_year = 1883

, thesis2_title ...

, and especially Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th ce ...

. In following Fabre's argument, with respect to Wright's existentialist proclivities during the period of 1946 to 1951, Hue Woodson suggests that Wright's exposure to Husserl and Heidegger "directly came as an intended consequence of the inadequacies of Sartre's synthesis of existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

and Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

for Wright." His Existentialist

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and value ...

phase was expressed in his second novel, '' The Outsider'' (1953), which described an African-American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also became friends with fellow expatriate writers Chester Himes

Chester Bomar Himes (July 29, 1909 – November 12, 1984) was an American writer. His works, some of which have been filmed, include '' If He Hollers Let Him Go'', published in 1945, and the Harlem Detective series of novels for which he is be ...

and James Baldwin. His relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay "Everybody's Protest Novel" (collected in ''Notes of a Native Son

''Notes of a Native Son'' is a collection of ten essays by James Baldwin, published in 1955, mostly tackling issues of race in America and Europe. The volume, as his first non-fiction book, compiles essays of Baldwin that had previously appear ...

''), in which he criticized Wright's portrayal of Bigger Thomas as stereotypical. In 1954 Wright published ''Savage Holiday''.

After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright continued to travel through Europe, Asia, and Africa. He drew material from these trips for numerous nonfiction works. In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology '' The God That Failed;'' his essay had been published in the '' Atlantic Monthly'' three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of ''Black Boy.'' He was invited to join the Congress for Cultural Freedom

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an anti-communist advocacy group founded in 1950. At its height, the CCF was active in thirty-five countries. In 1966 it was revealed that the CIA was instrumental in the establishment and funding of the ...

, which he rejected, correctly suspecting that it had connections with the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. Fearful of links between African Americans and communists, the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

had Wright under surveillance starting in 1943. With the heightened communist fears of the 1950s, Wright was blacklisted by Hollywood movie studio executives. But in 1950, he starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas (Wright was 42) in an Argentinian

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish ( masculine) or ( feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, ...

film version of ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

.''

In mid-1953, Wright traveled to the Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

, where Kwame Nkrumah was leading the country to independence from British rule, to be established as Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

. Before Wright returned to Paris, he gave a confidential report to the United States consulate in Accra on what he had learned about Nkrumah and his political party. After Wright returned to Paris, he met twice with an officer from the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

. The officer's report includes what Wright had learned from Nkrumah's adviser George Padmore

George Padmore (28 June 1903 – 23 September 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left his native Trinidad in 1924 to study medicine in the United States, where he also joined the Com ...

about Nkrumah's plans for the Gold Coast after independence. Padmore, a Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

ian living in London, believed Wright to be a good friend. His many letters in the Wright papers at Yale's Beinecke Library attest to this, and the two men continued their correspondence. Wright's book on his African journey, '' Black Power,'' was published in 1954; its London publisher was Dennis Dobson

Dennis Dobson (1919 – 1978)Lewis Foreman, Susan Foreman''London: A Musical Gazetteer'' Yale University Press, 2005, p. 327. was a British book publisher who was the eponymous founder of a small but respected company in London.

Background

Set up ...

, who also published Padmore's work.

Whatever political motivations Wright had for reporting to American officials, he was also an American who wanted to stay abroad and needed their approval to have his passport renewed. According to Wright biographer Addison Gayle, a few months later Wright talked to officials at the American embassy in Paris about people he had met in the Communist Party; at the time these individuals were being prosecuted in the US under the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

.

Historian Carol Polsgrove explored why Wright appeared to have little to say about the increasing activism of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

during the 1950s in the United States. She found that Wright was under what his friend Chester Himes called "extraordinary pressure" to avoid writing about the US. As ''Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when ...

'' magazine delayed publishing his essay, "I Choose Exile," Wright finally suggested publishing it in a white periodical. He believed that "a white periodical would be less vulnerable to accusations of disloyalty." He thought the '' Atlantic Monthly'' was interested, but in the end, the piece went unpublished.Polsgrove, ''Divided Minds'', pp. 80–81.

In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

for the Bandung Conference. He recorded his observations on the conference as well as on Indonesian cultural conditions in '' The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference.'' Wright was enthusiastic about the possibilities posed by this meeting of newly independent, former colonial nations. He gave at least two lectures to Indonesian cultural groups, including PEN Club

PEN International (known as International PEN until 2010) is a worldwide association of writers, founded in London in 1921 to promote friendship and intellectual co-operation among writers everywhere. The association has autonomous Internation ...

Indonesia, and he interviewed Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write ''The Color Curtain.'' Several Indonesian artists and intellectuals whom Wright met, later commented on how he had depicted Indonesian cultural conditions in his travel writing

Travel is the movement of people between distant geographical locations. Travel can be done by foot, bicycle, automobile, train, boat, bus, airplane, ship or other means, with or without luggage, and can be one way or round trip. Travel c ...

.

Other works by Wright included ''White Man, Listen!'' (1957) and a novel ''The Long Dream'' (1958), which was adapted as a play and produced in New York in 1960 by Ketti Frings

Ketti Frings (28 February 1909 – 11 February 1981) was an American writer, playwright, and screenwriter who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1958.

Biography

Early years

Born Katherine Hartley in Columbus, Ohio, Frings attended Principia College, began ...

. It explores the relationship between a man named Fish and his father. A collection of short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

, ''Eight Men,'' was published posthumously in 1961, shortly after Wright's death. These works dealt primarily with the poverty, anger, and protests of northern and southern urban black Americans.

His agent, Paul Reynolds, sent strongly negative criticism of Wright's 400-page ''Island of Hallucinations'' manuscript in February 1959. Despite that, in March Wright outlined a novel in which his character Fish was to be liberated from racial conditioning and become dominating. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics had become increasingly submissive to United States pressure. The peaceful Parisian atmosphere he had enjoyed had been shattered by quarrels and attacks instigated by enemies of the expatriate black writers.

On June 26, 1959, after a party marking the French publication of ''White Man, Listen!,'' Wright became ill. He suffered a virulent attack of amoebic dysentery

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba ''Entamoeba histolytica''. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic u ...

, probably contracted during his 1953 stay on the Gold Coast. By November 1959 his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.

On February 19, 1960, Wright learned from his agent Reynolds that the New York premiere of the stage adaptation of ''The Long Dream'' received such bad reviews that the adapter, Ketti Frings, had decided to cancel further performances. Meanwhile, Wright was running into added problems trying to get ''The Long Dream'' published in France. These setbacks prevented his finishing revisions of ''Island of Hallucinations,'' for which he was trying to get a publication commitment from Doubleday and Company.

In June 1960, Wright recorded a series of discussions for French radio, dealing primarily with his books and literary career. He also addressed the racial situation in the United States and the world, and specifically denounced American policy in Africa. In late September, to cover extra expenses for his daughter Julia's move from London to Paris to attend the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, Wright wrote blurbs for record jackets for Nicole Barclay, director of the largest record company in Paris.

In spite of his financial straits, Wright refused to compromise his principles. He declined to participate in a series of programs for Canadian radio because he suspected American control. For the same reason, he rejected an invitation from the Congress for Cultural Freedom to go to India to speak at a conference in memory of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. Still interested in literature, Wright helped Kyle Onstott get his novel '' Mandingo'' (1957) published in France.

Wright's last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960, in his polemical lecture, "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States," delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris

The American Church in Paris (formerly the American Chapel in Paris) was the first American church established outside the United States. It traces its roots back to 1814, and the present church building - located at 65 Quai d'Orsay in the 7th ...

. He argued that American society reduced the most militant members of the black community to slaves whenever they wanted to question the racial status quo. He offered as proof the subversive attacks of the Communists against ''Native Son'' and the quarrels which James Baldwin and other authors sought with him. On November 26, 1960, Wright talked enthusiastically with Langston Hughes about his work ''Daddy Goodness'' and gave him the manuscript.

Wright died in Paris on November 28, 1960, of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

at the age of 52. He was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figure ...

. Wright's daughter Julia has claimed that her father was murdered.

A number of Wright's works have been published posthumously. In addition, some of Wright's more shocking passages dealing with race, sex, and politics were cut or omitted before original publication of works during his lifetime. In 1991, unexpurgated versions of ''Native Son,'' ''Black Boy,'' and his other works were published. In addition, in 1994, his novella ''Rite of Passage'' was published for the first time.

In the last years of his life, Wright had become enamored of the Japanese poetic form haiku

is a type of short form poetry originally from Japan. Traditional Japanese haiku consist of three phrases that contain a ''kireji'', or "cutting word", 17 '' on'' (phonetic units similar to syllables) in a 5, 7, 5 pattern, and a ''kigo'', or s ...

and wrote more than 4,000 such short poems. In 1998 a book was published (''Haiku: This Other World'') with 817 of his own favorite haiku. Many of these haiku have an uplifting quality even as they deal with coming to terms with loneliness, death, and the forces of nature.

A collection of Wright's travel writings was published by the University Press of Mississippi

The University Press of Mississippi, founded in 1970, is a publisher that is sponsored by the eight state universities in Mississippi.

Universities

*Alcorn State University

*Delta State University

* Jackson State University

*Mississippi State U ...

in 2001. At his death, Wright left an unfinished book, ''A Father's Law,'' dealing with a black policeman and the son he suspects of murder. His daughter Julia Wright published ''A Father's Law'' in January 2008. An omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title ''Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain''; and ''White Man, Listen!''

Personal life

In August 1939, withRalph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel '' Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

as best man, Wright married Dhimah Rose Meidman, a modern-dance teacher of Russian Jewish ancestry. It was a short-lived marriage that ended a year later.

On March 12, 1941, he married Ellen Poplar (''née'' Poplowitz), a Communist organizer from Brooklyn. They had two daughters: Julia, born in 1942, and Rachel, born in 1949.

Ellen Wright, who died on April 6, 2004, aged 92, was the executor of Wright's estate. In that capacity, she sued a biographer, the poet and writer Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. H ...

, in '' Wright v. Warner Books, Inc.'' She was a literary agent, numbering among her clients Simone de Beauvoir, Eldridge Cleaver

Leroy Eldridge Cleaver (August 31, 1935 – May 1, 1998) was an American writer and political activist who became an early leader of the Black Panther Party.

In 1968, Cleaver wrote '' Soul on Ice'', a collection of essays that, at the time of i ...

, and Violette Leduc

Violette Leduc (7 April 1907 – 28 May 1972) was a French writer.

Early life and education

She was born in Arras, Pas de Calais, France, on 7 April 1907. She was the illegitimate daughter of a servant girl, Berthe Leduc, and André Debaralle ...

.

Awards and honors

* The Spingarn Medal in 1941 from the NAACP * Guggenheim Fellowship in 1939 * ''Story

Story or stories may refer to:

Common uses

* Story, a narrative (an account of imaginary or real people and events)

** Short story, a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting

* Story (American English), or storey (British ...

'' Magazine Award in 1938.

* In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. The 61-cent, two-ounce rate stamp is the 25th installment of the literary arts series, and features a portrait of Wright in front of snow-swept tenements on the South Side of Chicago, a scene that recalls the setting of ''Native Son.''

* In 2010, Wright was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

* In 2012, the Historic Districts Council and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is the New York City agency charged with administering the city's Landmarks Preservation Law. The LPC is responsible for protecting New York City's architecturally, historically, and cu ...

, in collaboration with the Fort Greene Association and writer/musician Carl Hancock Rux

Carl Hancock Rux () is an American poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, recording artist, journalist, curator and conceptual installation artist working in text, dance, ritualized performance, audio, video, and photography. Described in the NY T ...

, erected a cultural medallion at 175 Carlton Avenue, Brooklyn, where Wright lived in 1938 and completed ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

.'' The group unveiled the plaque at a public ceremony with guest speakers, including playwright Lynn Nottage and Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz

Martin Markowitz (born February 14, 1945) is an American politician who served as the borough president of Brooklyn, New York City. He was first elected in 2001 after serving 23 years as a New York State Senator. His third and final term end ...

.

Legacy

''Black Boy'' became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945. Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots. Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism during a period when the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.

During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.

While interest in ''Black Boy'' ebbed during the 1950s, this has remained one of his best selling books. Since the late 20th century, critics have had a resurgence of interest in it. ''Black Boy'' remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society strongly influenced the works of African-American writers who followed, such as James Baldwin and

''Black Boy'' became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945. Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots. Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism during a period when the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.

During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.

While interest in ''Black Boy'' ebbed during the 1950s, this has remained one of his best selling books. Since the late 20th century, critics have had a resurgence of interest in it. ''Black Boy'' remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society strongly influenced the works of African-American writers who followed, such as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel '' Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

.

It is generally agreed that the influence of Wright's ''Native Son'' is not a matter of literary style or technique. Rather, this book affected ideas and attitudes, and ''Native Son'' has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle," said writer Amiri Baraka.

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars published critical essays about Wright in prestigious journals. Richard Wright conferences were held on university campuses from Mississippi to New Jersey. A new film version of ''Native Son,'' with a screenplay by Richard Wesley, was released in December 1986. Certain Wright novels became required reading in a number of American high schools, universities and colleges.

Recent critics have called for a reassessment of Wright's later work in view of his philosophical project. Notably, Paul Gilroy

Paul Gilroy (born 16 February 1956) is an English sociologist and cultural studies scholar who is the founding Director of the Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Race and Racism at University College, London (UCL). Gilroy is the 2019 ...

has argued that "the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary inquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing."

Wright was featured in a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project entitled ''Soul of a People: Writing America's Story'' (2009). His life and work during the 1930s is highlighted in the companion book, ''Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America''.

Publications

; Collections: * Richard Wright: ''Early Works'' (Arnold Rampersad

Arnold Rampersad (born 13 November 1941) is a biographer, literary critic, and academic, who was born in Trinidad and Tobago and moved to the US in 1965. The first volume (1986) of his ''Life of Langston Hughes'' was a finalist for the Pulitzer ...

, ed.) (Library of America

The Library of America (LOA) is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature. Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LOA has published over 300 volumes by authors rang ...

, 1989),

* Richard Wright: ''Later Works'' (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of America

The Library of America (LOA) is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature. Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LOA has published over 300 volumes by authors rang ...

, 1991).

; Drama:

* ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

: The Biography of a Young American'' with Paul Green (New York: Harper, 1941)

; Fiction:

* '' Uncle Tom's Children'' (New York: Harper, 1938) (collection of novellas

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

)

* ''The Man Who Was Almost a Man

"The Man Who Was Almost a Man", also known as "Almos' a Man", is a short story by Richard Wright. It was originally published in 1940 in ''Harper's Bazaar'' magazine, and again in 1961 as part of Wright's compilation ''Eight Men''. The story cen ...

'' (New York: Harper, 1940) (short story)

* ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing f ...

'' (New York: Harper, 1940) (novel)

* ''The Man Who Lived Underground'' (1942) (short story)

* '' The Outsider'' (New York: Harper, 1953) (novel)

* ''Savage Holiday'' (New York: Avon, 1954) (novel)

* ''The Long Dream'' (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1958) (novel)

* ''Eight Men'' (Cleveland and New York: World, 1961) (collection of short stories)

* ''Lawd Today'' (New York: Walker, 1963) (novel)

* ''Rite of Passage'' (New York: HarperCollins, 1994) (short story)

* ''A Father's Law'' (London: Harper Perennial, 2008) (unfinished novel)

* ''The Man Who Lived Underground'' (Library of America, 2021) (short story)

; Non-fiction:

* ''How "Bigger" Was Born; Notes of a Native Son'' (New York: Harper, 1940)

* ''12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States'' (New York: Viking, 1941)

* '' Black Boy'' (New York: Harper, 1945)

* ''Black Power'' (New York: Harper, 1954)

* '' The Color Curtain'' (Cleveland and New York: World, 1956)

* ''Pagan Spain'' (New York: Harper, 1957)

* ''Letters to Joe C. Brown'' (Kent State University Libraries, 1968)

* ''American Hunger'' (New York: Harper & Row, 1977)

* ''Conversations with Richard Wright'' (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1993).

* ''Black Power: Three Books from Exile: "Black Power"; "The Color Curtain"; and "White Man, Listen!"'' (Harper Perennial, 2008)

; Essays:

* ''The Ethics Of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch'' (1937)

* Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City

' (1945) * '' I Choose Exile'' (1951) * ''White Man, Listen!'' (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957) * ''Blueprint for Negro Literature'' (New York City, New York) (1937)

''ChickenBones: A Journal''.

References

Additional resources

Books

* Fabre, Michel. ''The World of Richard Wright'' (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1985). * Fabre, Michel. ''The unfinished quest of Richard Wright'' (U of Illinois Press, 1993). * Fishburn, Katherine. ''Richard Wright's Hero: The Faces of a Rebel-Victim'' (Scarecrow Press, 1977). * Rampersad, Arnold, ed. ''Richard Wright: A Collection of Critical Essays'' (1994) * Rowley, Hazel. ''Richard Wright: The life and times'' (U of Chicago Press, 2008). * Smith, Virginia Whatley, ed. ''Richard Wright Writing America at Home and from Abroad'' (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2016). * Ward, Jerry W., and Robert J. Butler, eds. ''The Richard Wright Encyclopedia'' (ABC-CLIO, 2008). * *Journal articles

* Alsen, Eberhard. "'Toward The Living Sun': Richard Wright's Change Of Heart From 'The Outsider' To 'The Long Dream, ''CLA Journal

The College Language Association (CLA) is a professional association of Black scholars and educators who teach English and foreign languages. Founded in 1937 by a group of African-American language and literature scholars, the organization "serves ...

'' 38.2 (1994): 211–227online

* * Bone, Robert. "Richard Wright and the Chicago Renaissance", ''

Callaloo

Callaloo (many spelling variants, such as kallaloo, calaloo, calalloo, calaloux or callalloo; ) is a popular Caribbean vegetable dish. There are many variants across the Caribbean, depending on the availability of local vegetables. The main in ...

'' 28 (1986): 446–468online

* Burgum, Edwin Berry. "The Promise of Democracy and the Fiction of Richard Wright", '' Science & Society'', vol. 7, no. 4 (Fall 1943), pp. 338–352

In JSTOR

* Bradley, M. (2018). "Richard Wright, Bandung, and the Poetics of the Third World." ''Modern American History,'' ''1''(1), 147–150. * Cauley, Anne O. "A Definition of Freedom in the Fiction of Richard Wright", ''CLA Journal'' 19.3 (1976): 327–346

online

* Cobb, Nina Kressner. "Richard Wright: exile and existentialism", ''

Phylon

''Phylon'' (subtitle: ''the Clark Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture'') is a semi-annual peer-reviewed academic journal covering culture in the United States from an African-American perspective. It was established in 1940 by W. E. B. Du ...

'' 40.4 (1979): 362–374online

* * Gines, Kathryn T. "'The Man Who Lived Underground': Jean-Paul Sartre And the Philosophical Legacy of Richard Wright", ''Sartre Studies International'' 17.2 (2011): 42–59. * Knapp, Shoshana Milgram. "Recontextualizing Richard Wright's The Outsider: Hugo, Dostoevsky, Max Eastman, and Ayn Rand", in ''Richard Wright in a Post-Racial Imaginary'' (2014), pp. 99–112. * Meyerson, Gregory. "Aunt Sue's Mistake: False Consciousness in Richard Wright's 'Bright and Morning Star, in ''Reconstruction: Studies in Culture: 2008'' 8#

online

* * Veninga, Jennifer Elisa. "Richard Wright: Kierkegaard's Influence as Existentialist Outsider", in ''Kierkegaard's Influence on Social-Political Thought'' (Routledge, 2016), pp. 281–298. * Widmer, Kingsley, and Richard Wright. "The Existential Darkness: Richard Wright's 'The Outsider], ''Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature'' 1.3 (1960): 13–21

online

* Woodson, Hue. "Heidegger and The Outsider, Savage Holiday, and The Long Dream" in ''Critical Insights: Richard Wright''. Ed. Kimberly Drake (Amenia, NY: Grey House, 2019).

Archival materials

Richard Wright Papers

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Richard Wright Collection (MUM00488)

at the University of Mississippi.

Richard Wright Book Project

materials in the papers of sociologist Horace R. Clayton, Jr. at

Chicago Public Library

The Chicago Public Library (CPL) is the public library system that serves the City of Chicago in the U.S. state of Illinois. It consists of 81 locations, including a central library, two regional libraries, and branches distributed throughout the ...

External links

* * The story of his life is retold in the radio dramaBlack Boy

, a presentation from ''

Destination Freedom

''Destination Freedom'' was a weekly radio program produced by WMAQ in Chicago from 1948 to 1950 that presented biographical histories of prominent African-Americans such as George Washington Carver, Satchel Paige, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tu ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wright, Richard

1908 births

1960 deaths

20th-century American novelists

African-American agnostics

African-American former Christians

African-American novelists

African-American poets

American communists

American autobiographers

American emigrants to France

American expatriates in France

American male novelists

Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

English-language haiku poets

Existentialists

French people of African-American descent

Hollywood blacklist

Members of the Communist Party USA

Writers from Chicago

People from Franklin County, Mississippi

Writers from Jackson, Mississippi

Federal Writers' Project people

Postmodern writers

Spingarn Medal winners

American socialists

20th-century American poets

American male poets

African-American short story writers

American male short story writers

20th-century American short story writers

Novelists from Illinois

Novelists from Mississippi

American male non-fiction writers

People from Fort Greene, Brooklyn

20th-century American male writers

Deaths from coronary thrombosis