Rhizobium radiobacter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Agrobacterium radiobacter'' (more commonly known as ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'') is the causal agent of crown gall disease (the formation of

The T-DNA must be cut out of the circular plasmid. A VirD1/D2 complex nicks the DNA at the left and right border sequences. The VirD2 protein is covalently attached to the 5' end. VirD2 contains a motif that leads to the nucleoprotein complex being targeted to the type IV secretion system (T4SS).

In the cytoplasm of the recipient cell, the T-DNA complex becomes coated with VirE2 proteins, which are exported through the T4SS independently from the T-DNA complex.

The T-DNA must be cut out of the circular plasmid. A VirD1/D2 complex nicks the DNA at the left and right border sequences. The VirD2 protein is covalently attached to the 5' end. VirD2 contains a motif that leads to the nucleoprotein complex being targeted to the type IV secretion system (T4SS).

In the cytoplasm of the recipient cell, the T-DNA complex becomes coated with VirE2 proteins, which are exported through the T4SS independently from the T-DNA complex.

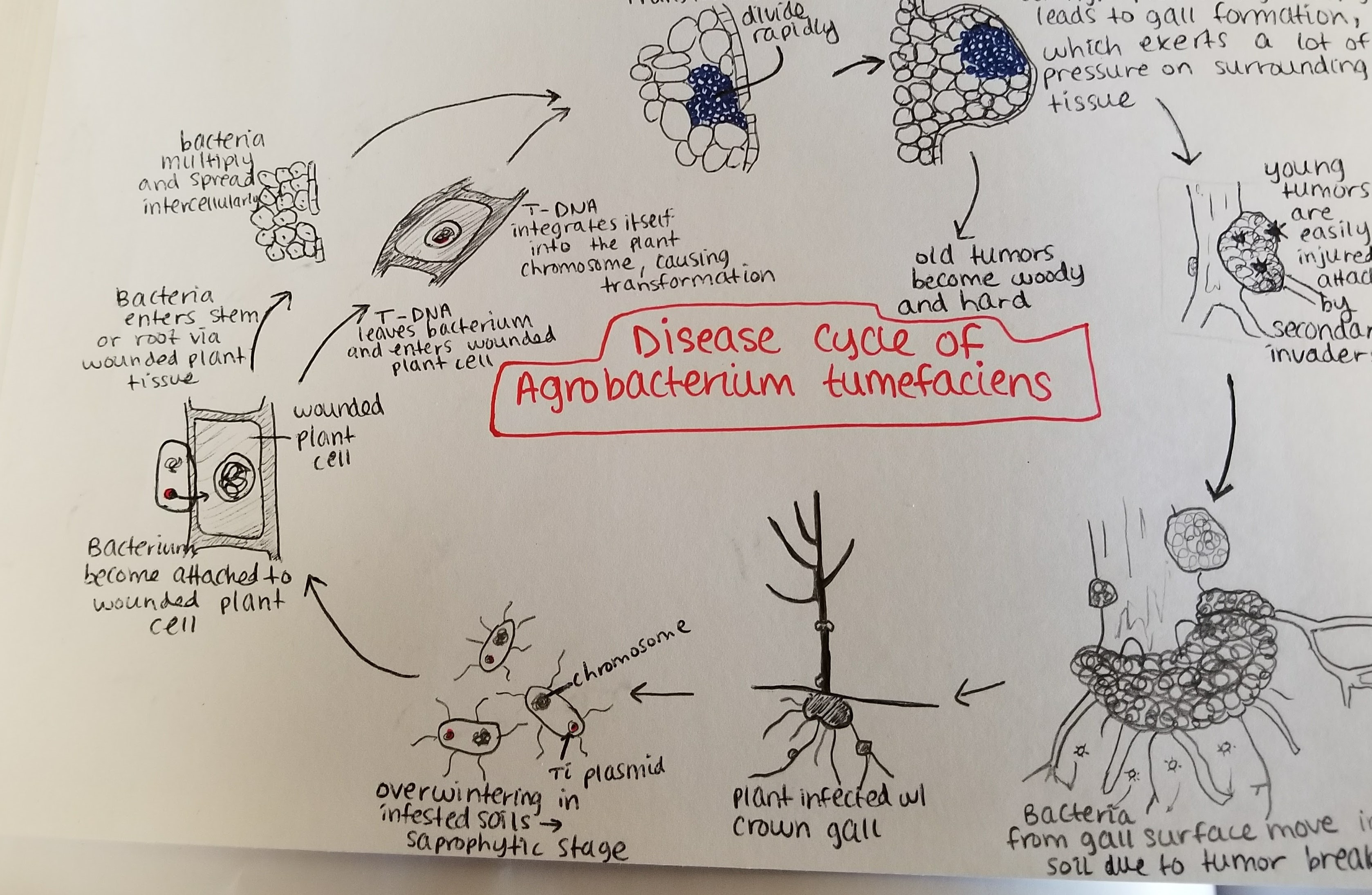

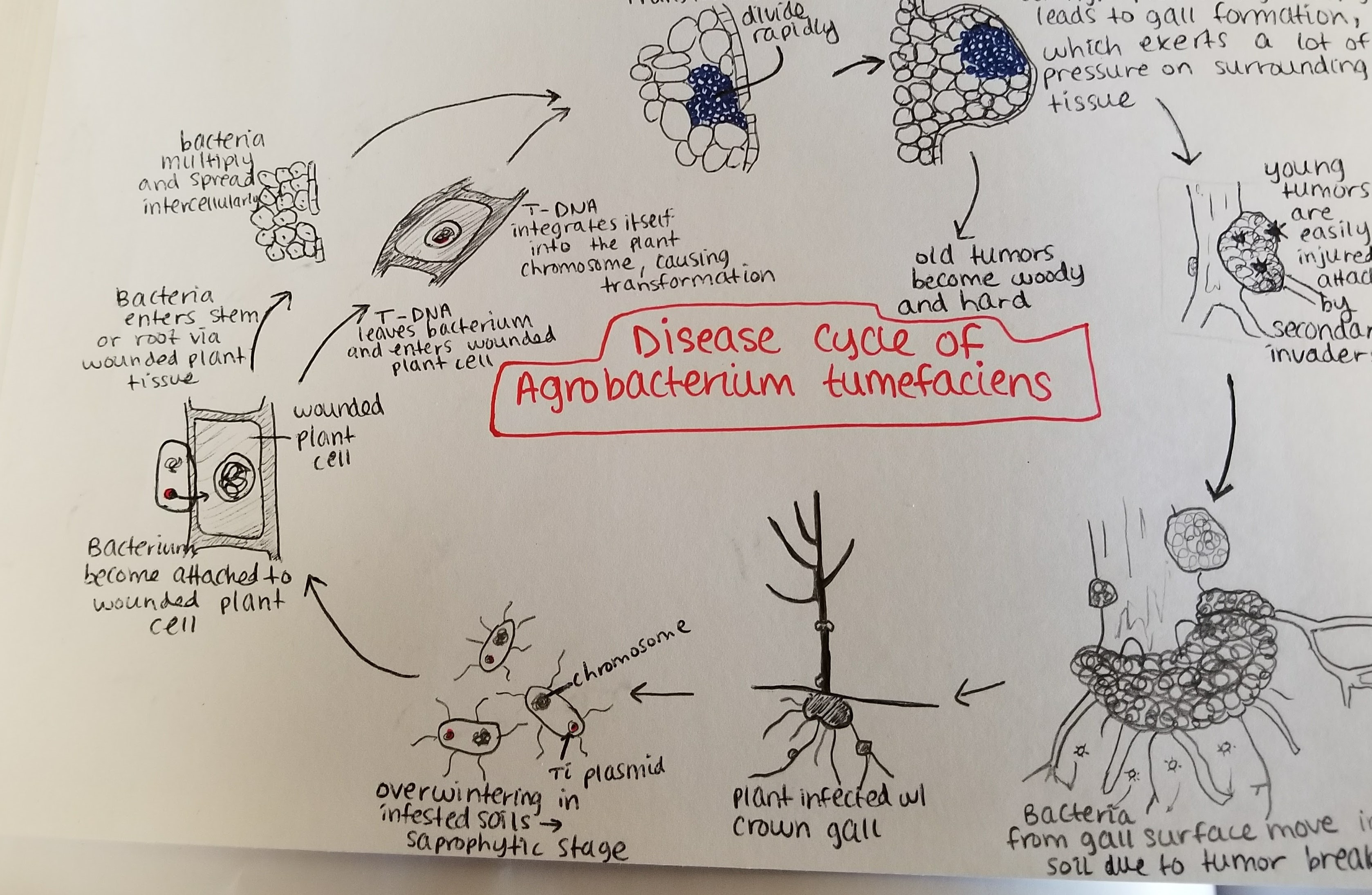

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' overwinters in infested soils. ''Agrobacterium'' species live predominantly saprophytic lifestyles, so its common even for plant-parasitic species of this genus to survive in the soil for lengthy periods of time, even without host plant presence. When there is a host plant present, however, the bacteria enter the plant tissue via recent wounds or natural openings of roots or stems near the ground. These wounds may be caused by cultural practices, grafting, insects, etc. Once the bacteria have entered the plant, they occur intercellularly and stimulate surrounding tissue to proliferate due to cell transformation. ''Agrobacterium'' performs this control by inserting the plasmid T-DNA into the plant's genome. See above for more details about the process of plasmid DNA insertion into the host genome. Excess growth of the plant tissue leads to gall formation on the stem and roots. These tumors exert significant pressure on the surrounding plant tissue, which causes this tissue to become crushed and/or distorted. The crushed vessels lead to reduced water flow in the xylem. Young tumors are soft and therefore vulnerable to secondary invasion by insects and saprophytic microorganisms. This secondary invasion causes the breakdown of the peripheral cell layers as well as tumor discoloration due to decay. Breakdown of the soft tissue leads to release of the ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' into the soil allowing it to restart the disease process with a new host plant.

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' overwinters in infested soils. ''Agrobacterium'' species live predominantly saprophytic lifestyles, so its common even for plant-parasitic species of this genus to survive in the soil for lengthy periods of time, even without host plant presence. When there is a host plant present, however, the bacteria enter the plant tissue via recent wounds or natural openings of roots or stems near the ground. These wounds may be caused by cultural practices, grafting, insects, etc. Once the bacteria have entered the plant, they occur intercellularly and stimulate surrounding tissue to proliferate due to cell transformation. ''Agrobacterium'' performs this control by inserting the plasmid T-DNA into the plant's genome. See above for more details about the process of plasmid DNA insertion into the host genome. Excess growth of the plant tissue leads to gall formation on the stem and roots. These tumors exert significant pressure on the surrounding plant tissue, which causes this tissue to become crushed and/or distorted. The crushed vessels lead to reduced water flow in the xylem. Young tumors are soft and therefore vulnerable to secondary invasion by insects and saprophytic microorganisms. This secondary invasion causes the breakdown of the peripheral cell layers as well as tumor discoloration due to decay. Breakdown of the soft tissue leads to release of the ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' into the soil allowing it to restart the disease process with a new host plant.

Host, environment, and pathogen are extremely important concepts in regards to plant pathology. ''Agrobacteria'' have the widest host range of any plant pathogen, so the main factor to take into consideration in the case of crown gall is environment. There are various conditions and factors that make for a conducive environment for ''A. tumefaciens'' when infecting its various hosts. The bacterium can't penetrate the host plant without an entry point such as a wound. Factors leading to wounds in plants include cultural practices, grafting, freezing injury, growth cracks, soil insects, and other animals in the environment causing damage to the plant. Consequently, in exceptionally harsh winters, it is common to have an increased incidence of crown gall due to the weather-related damage. Along with this, there are methods of mediating infection of the host plant. For example, nematodes can act as a vector to introduce ''Agrobacterium'' into plant roots. More specifically, the root parasitic nematodes damage the plant cell, creating a wound for the bacteria to enter through. Finally, temperature is a factor when considering ''A. tumefaciens'' infection. The optimal temperature for crown gall formation due to this bacterium is 22 °C because of the thermosensitivity of T-DNA transfer. Tumor formation is significantly reduced at higher temperature conditions.

Host, environment, and pathogen are extremely important concepts in regards to plant pathology. ''Agrobacteria'' have the widest host range of any plant pathogen, so the main factor to take into consideration in the case of crown gall is environment. There are various conditions and factors that make for a conducive environment for ''A. tumefaciens'' when infecting its various hosts. The bacterium can't penetrate the host plant without an entry point such as a wound. Factors leading to wounds in plants include cultural practices, grafting, freezing injury, growth cracks, soil insects, and other animals in the environment causing damage to the plant. Consequently, in exceptionally harsh winters, it is common to have an increased incidence of crown gall due to the weather-related damage. Along with this, there are methods of mediating infection of the host plant. For example, nematodes can act as a vector to introduce ''Agrobacterium'' into plant roots. More specifically, the root parasitic nematodes damage the plant cell, creating a wound for the bacteria to enter through. Finally, temperature is a factor when considering ''A. tumefaciens'' infection. The optimal temperature for crown gall formation due to this bacterium is 22 °C because of the thermosensitivity of T-DNA transfer. Tumor formation is significantly reduced at higher temperature conditions.

"''Agrobacterium fabrum''" C58 Genome Page

nbsp;— as sequenced by Cereon Genomics/University of Richmond {{Authority control Gram-negative bacteria Bacterial plant pathogens and diseases Bacterial grape diseases Bacteria described in 1907 Rhizobiaceae

tumour

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

s) in over 140 species of eudicots. It is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wa ...

soil bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were amon ...

. Symptoms are caused by the insertion of a small segment of DNA (known as the T-DNA

The transfer DNA (abbreviated T-DNA) is the transferred DNA of the tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid of some species of bacteria such as '' Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' and '' Agrobacterium rhizogenes(actually an Ri plasmid)''. The T-DNA is transferred ...

, for 'transfer DNA', not to be confused with tRNA that transfers amino acids during protein synthesis), from a plasmid into the plant cell, which is incorporated at a semi-random location into the plant genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding g ...

. Plant genomes can be engineered by use of ''Agrobacterium

''Agrobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. '' Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is the most commonly studied species in this genus. ''Agrobacterium'' i ...

'' for the delivery of sequences hosted in T-DNA binary vectors.

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is an Alphaproteobacterium

Alphaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria). The Magnetococcales and Mariprofundales are considered basal or sister to the Alphaproteobacteria. The Alphaproteobacteria are highly diverse a ...

of the family Rhizobiaceae

The Rhizobiaceae is a family of Pseudomonadota comprising multiple subgroups that enhance and hinder plant development. Some bacteria found in the family are used for plant nutrition and collectively make up the rhizobia. Other bacteria such as ...

, which includes the nitrogen-fixing

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular nitrogen (), with a strong triple covalent bond, in the air is converted into ammonia () or related nitrogenous compounds, typically in soil or aquatic systems but also in industry. Atm ...

legume symbionts. Unlike the nitrogen-fixing symbionts, tumor-producing ''Agrobacterium'' species are pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

ic and do not benefit the plant. The wide variety of plants affected by ''Agrobacterium'' makes it of great concern to the agriculture industry.

Economically, ''A. tumefaciens'' is a serious pathogen of walnuts

A walnut is the edible seed of a drupe of any tree of the genus ''Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, ''Juglans regia''.

Although culinarily considered a "nut" and used as such, it is not a true bot ...

, grape vine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 79 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, ...

s, stone fruit

In botany, a drupe (or stone fruit) is an indehiscent fruit in which an outer fleshy part ( exocarp, or skin, and mesocarp, or flesh) surrounds a single shell (the ''pit'', ''stone'', or ''pyrena'') of hardened endocarp with a seed (''kernel' ...

s, nut

Nut often refers to:

* Nut (fruit), fruit composed of a hard shell and a seed, or a collective noun for dry and edible fruits or seeds

* Nut (hardware), fastener used with a bolt

Nut or Nuts may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Co ...

trees, sugar beets, horse radish

Horseradish (''Armoracia rusticana'', syn. ''Cochlearia armoracia'') is a perennial plant of the family Brassicaceae (which also includes mustard, wasabi, broccoli, cabbage, and radish). It is a root vegetable, cultivated and used worldwide as ...

, and rhubarb, and the persistent nature of the tumors or galls caused by the disease make it particularly harmful for perennial crops.

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' grows optimally at 28 °C. The doubling time can range from 2.5–4h depending on the media, culture format, and level of aeration. At temperatures above 30 °C, ''A. tumefaciens'' begins to experience heat shock which is likely to result in errors in cell division.

Conjugation

To bevirulent

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ...

, the bacterium contains tumour-inducing plasmid (Ti plasmid or pTi), of 200 kbp, which contains the T-DNA and all the gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s necessary to transfer it to the plant cell. Many strains of ''A. tumefaciens'' do not contain a pTi.

Since the Ti plasmid is essential to cause disease, prepenetration events in the rhizosphere

The rhizosphere is the narrow region of soil or substrate that is directly influenced by root secretions and associated soil microorganisms known as the root microbiome. Soil pores in the rhizosphere can contain many bacteria and other microo ...

occur to promote bacterial conjugation - exchange of plasmids amongst bacteria. In the presence of opines

Opines are low molecular weight compounds found in plant crown gall tumors or hairy root tumors produced by pathogenic bacteria of the genus ''Agrobacterium'' and ''Rhizobium''. Opine biosynthesis is catalyzed by specific enzymes encoded by gene ...

, ''A. tumefaciens'' produces a diffusible conjugation signal called 30C8HSL or the ''Agrobacterium'' autoinducer . This activates the transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The f ...

TraR, positively regulating the transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of genes required for conjugation .

Infection methods

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' infects the plant through its Ti plasmid. The Ti plasmid integrates a segment of its DNA, known as T-DNA, into the chromosomal DNA of its host plant cells. ''A. tumefaciens'' has flagella that allow it to swim through thesoil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt

Dirt is an unclean matter, especially when in contact with a person's clothes, skin, or possessions. In such cases, they are said to become dirty.

Common types of dirt include:

* Debri ...

towards photoassimilate In botany, a photoassimilate is one of a number of biological compounds formed by assimilation using light-dependent reactions. This term is most commonly used to refer to the energy-storing monosaccharides produced by photosynthesis in the leaves ...

s that accumulate in the rhizosphere around roots. Some strains may chemotactically move towards chemical exudates from plants, such as acetosyringone

Acetosyringone is a phenolic natural product and a chemical compound related to acetophenone and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol. It was first described in relation to lignan/phenylpropanoid-type phytochemicals, with isolation from a variety of plant source ...

and sugars, which indicate the presence of a wound in the plant through which the bacteria may enter. Phenolic compounds are recognised by the VirA protein VirA is a protein histidine kinase which senses certain sugars and phenolic compounds. These compounds are typically found from wounded plants, and as a result VirA is used by ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' to locate potential host organisms for inf ...

, a transmembrane protein encoded in the virA gene on the Ti plasmid. Sugars are recognised by the chvE protein, a chromosomal gene-encoded protein located in the periplasmic space.

At least 25 ''vir'' genes on the Ti plasmid are necessary for tumor induction . In addition to their perception role, ''virA'' and ''chvE'' induce other ''vir'' genes. The VirA protein has auto kinase activity: it phosphorylates

In chemistry, phosphorylation is the attachment of a phosphate group to a molecule or an ion. This process and its inverse, dephosphorylation, are common in biology and could be driven by natural selection. Text was copied from this source, whi ...

itself on a histidine residue. Then the VirA protein phosphorylates the VirG protein on its aspartate residue. The virG protein is a cytoplasmic protein produced from the ''virG'' Ti plasmid gene. It is a transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The f ...

, inducing the transcription of the ''vir'' operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

s. The ChvE protein regulates the second mechanism of the ''vir'' genes' activation. It increases VirA protein sensitivity to phenolic compounds.

Attachment is a two-step process. Following an initial weak and reversible attachment, the bacteria synthesize cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell w ...

fibril

Fibrils (from the Latin ''fibra'') are structural biological materials found in nearly all living organisms. Not to be confused with fibers or filaments, fibrils tend to have diameters ranging from 10-100 nanometers (whereas fibers are micro ...

s that anchor them to the wounded plant cell to which they were attracted. Four main genes are involved in this process: ''chvA'', ''chvB'', ''pscA'', and ''att''. The products of the first three genes apparently are involved in the actual synthesis of the cellulose fibrils. These fibrils also anchor the bacteria to each other, helping to form a microcolony.

VirC, the most important virulent protein, is a necessary step in the recombination of illegitimate recolonization. It selects the section of the DNA in the host plant that will be replaced and it cuts into this strand of DNA.

After production of cellulose fibrils, a calcium-dependent outer membrane protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

called rhicadhesin is produced, which also aids in sticking the bacteria to the cell wall. Homologues of this protein can be found in other rhizobia. Currently, there are several reports on standardisation of protocol for the ''Agrobacterium''-mediated transformation. Effect of different parameters like, infection time, acetosyringone, DTT, cysteine have been studied in soybean (''Glycine max'')

Possible plant compounds that initiate ''Agrobacterium'' to infect plant cells:

*Acetosyringone

Acetosyringone is a phenolic natural product and a chemical compound related to acetophenone and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol. It was first described in relation to lignan/phenylpropanoid-type phytochemicals, with isolation from a variety of plant source ...

and other phenolic compounds

*alpha- Hydroxyacetosyringone

*Catechol

Catechol ( or ), also known as pyrocatechol or 1,2-dihydroxybenzene, is a toxic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is the ''ortho'' isomer of the three isomeric benzenediols. This colorless compound occurs naturally in trace amoun ...

*Ferulic acid

Ferulic acid is a hydroxycinnamic acid, an organic compound with the formula (CH3O)HOC6H3CH=CHCO2H. The name is derived from the genus ''Ferula'', referring to the giant fennel ('' Ferula communis''). Classified as a phenolic phytochemical, ferul ...

*Gallic acid

Gallic acid (also known as 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) is a trihydroxybenzoic acid with the formula C6 H2( OH)3CO2H. It is classified as a phenolic acid. It is found in gallnuts, sumac, witch hazel, tea leaves, oak bark, and other plants. I ...

*p-Hydroxybenzoic acid

4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, also known as ''p''-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA), is a monohydroxybenzoic acid, a phenolic derivative of benzoic acid. It is a white crystalline solid that is slightly soluble in water and chloroform but more soluble in polar ...

* Protocatechuic acid

*Pyrogallic acid

Pyrogallol is an organic compound with the formula C6H3(OH)3. It is a water-soluble, white solid although samples are typically brownish because of its sensitivity toward oxygen. It is one of three isomers of benzenetriols.

Production and reac ...

*Resorcylic acid Resorcylic acid is a type of dihydroxybenzoic acid. It may refer to:

*3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid

3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (α-resorcylic acid) is a dihydroxybenzoic acid. It is a colorless solid.

Preparation and occurrence

It is prepared by disu ...

*Sinapinic acid

Sinapinic acid, or sinapic acid (Sinapine - Origin: L. Sinapi, sinapis, mustard, Gr., cf. F. Sinapine.), is a small naturally occurring hydroxycinnamic acid. It is a member of the phenylpropanoid family. It is a commonly used matrix in MALDI mass ...

*Syringic acid

Syringic acid is a naturally occurring phenolic compound and dimethoxybenzene that is commonly found as a plant metabolite.

Natural occurrence

Syringic acid can be found in several plants including ''Ardisia elliptica'' and '' Schumannianthus ...

*Vanillin

Vanillin is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a phenolic aldehyde. Its functional groups include aldehyde, hydroxyl, and ether. It is the primary component of the extract of the vanilla bean. Synthetic vanillin is now u ...

Formation of the T-pilus

To transfer the T-DNA into the plant cell, ''A. tumefaciens'' uses a type IV secretion mechanism, involving the production of a T-pilus

A pilus (Latin for 'hair'; plural: ''pili'') is a hair-like appendage found on the surface of many bacteria and archaea. The terms ''pilus'' and '' fimbria'' (Latin for 'fringe'; plural: ''fimbriae'') can be used interchangeably, although some r ...

. When acetosyringone and other substances are detected, a signal transduction event activates the expression of 11 genes within the VirB operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

which are responsible for the formation of the T-pilus.

The pro-pilin is formed first. This is a polypeptide of 121 amino acids which requires processing by the removal of 47 residues to form a T-pilus subunit. The subunit is circularized by the formation of a peptide bond between the two ends of the polypeptide.

Products of the other VirB genes are used to transfer the subunits across the plasma membrane. Yeast two-hybrid

Two-hybrid screening (originally known as yeast two-hybrid system or Y2H) is a molecular biology technique used to discover protein–protein interactions (PPIs) and protein–DNA interactions by testing for physical interactions (such as bind ...

studies provide evidence that VirB6, VirB7, VirB8, VirB9 and VirB10 may all encode

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) is a public research project which aims to identify functional elements in the human genome.

ENCODE also supports further biomedical research by "generating community resources of genomics data, software ...

components of the transporter. An ATPase for the active transport

In cellular biology, ''active transport'' is the movement of molecules or ions across a cell membrane from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration—against the concentration gradient. Active transport requires cellul ...

of the subunits would also be required.

Transfer of T-DNA into the plant cell

Nuclear localization signal A nuclear localization signal ''or'' sequence (NLS) is an amino acid sequence that 'tags' a protein for import into the cell nucleus by nuclear transport. Typically, this signal consists of one or more short sequences of positively charged lysines o ...

s, or NLSs, located on the VirE2 and VirD2, are recognised by the importin alpha protein, which then associates with importin beta and the nuclear pore complex

A nuclear pore is a part of a large complex of proteins, known as a nuclear pore complex that spans the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are approximately 1,000 nuclear pore complexe ...

to transfer the T-DNA into the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

* Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucl ...

. VIP1 also appears to be an important protein in the process, possibly acting as an adapter to bring the VirE2 to the importin. Once inside the nucleus, VIP2 may target the T-DNA to areas of chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in r ...

that are being actively transcribed, so that the T-DNA can integrate into the host genome.

Genes in the T-DNA

Hormones

To cause gall formation, the T-DNA encodes genes for the production of auxin or indole-3-acetic acid via the IAM pathway. This biosynthetic pathway is not used in many plants for the production of auxin, so it means the plant has no molecular means of regulating it and auxin will be produced constitutively. Genes for the production ofcytokinin

Cytokinins (CK) are a class of plant hormones that promote cell division, or cytokinesis, in plant roots and shoots. They are involved primarily in cell growth and differentiation, but also affect apical dominance, axillary bud growth, and le ...

s are also expressed. This stimulates cell proliferation and gall formation.

Opines

The T-DNA contains genes for encoding enzymes that cause the plant to create specializedamino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

derivatives which the bacteria can metabolize

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

, called opines

Opines are low molecular weight compounds found in plant crown gall tumors or hairy root tumors produced by pathogenic bacteria of the genus ''Agrobacterium'' and ''Rhizobium''. Opine biosynthesis is catalyzed by specific enzymes encoded by gene ...

. Opines

Opines are low molecular weight compounds found in plant crown gall tumors or hairy root tumors produced by pathogenic bacteria of the genus ''Agrobacterium'' and ''Rhizobium''. Opine biosynthesis is catalyzed by specific enzymes encoded by gene ...

are a class of chemicals that serve as a source of nitrogen for ''A. tumefaciens'', but not for most other organisms. The specific type of opine produced by ''A. tumefaciens'' C58 infected plants is nopaline (Escobar ''et al.'', 2003).

Two nopaline type Ti plasmid

A tumour inducing (Ti) plasmid is a plasmid found in pathogenic species of ''Agrobacterium'', including ''A. tumefaciens, ''A. rhizogenes'', ''A. rubi'' and ''A. vitis''.

Evolutionarily, the Ti plasmid is part of a family of plasmids carried b ...

s, pTi-SAKURA and pTiC58, were fully sequenced. "''A. fabrum''" C58, the first fully sequenced pathovar

A pathovar is a bacterial strain or set of strains with the same or similar characteristics, that is differentiated at infrasubspecific level from other strains of the same species or subspecies on the basis of distinctive pathogenicity to one o ...

, was first isolated from a cherry tree crown gall. The genome was simultaneously sequenced by Goodner ''et al.'' and Wood ''et al.'' in 2001. The genome of ''A. tumefaciens'' C58 consists of a circular chromosome, two plasmids, and a linear chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

. The presence of a covalently bonded circular chromosome is common to Bacteria, with few exceptions. However, the presence of both a single circular chromosome and single linear chromosome is unique to a group in this genus. The two plasmids are pTiC58, responsible for the processes involved in virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ...

, and pAtC58, once dubbed the "cryptic" plasmid.

The pAtC58 plasmid has been shown to be involved in the metabolism of opines and to conjugate with other bacteria in the absence of the pTiC58 plasmid. If the Ti plasmid is removed, the tumor growth that is the means of classifying this species of bacteria does not occur.

Biotechnological uses

The Asilomar Conference (Berg et al. 1975) established widespread agreement that recombinant techniques were insufficiently understood and needed to be tightly controlled. The DNA transmission capabilities of ''Agrobacterium'' have been vastly explored inbiotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used ...

as a means of inserting foreign genes into plants. Shortly after Asilomar, Marc Van Montagu

Marc, Baron Van Montagu (born 10 November 1933 in Ghent) is a Belgian molecular biologist. He was full professor and director of the Laboratory of Genetics at the faculty of Sciences at Ghent University (Belgium) and scientific director of the ...

and Jeff Schell

Jozef Stefaan "Jeff", Baron Schell (20 July 1935 – 17 April 2003) was a Belgian molecular biologist.

Schell studied zoology and microbiology at the University of Ghent, Belgium. From 1967 to 1995 he worked as a professor at the university. Fro ...

, (University of Ghent

Ghent University ( nl, Universiteit Gent, abbreviated as UGent) is a public research university located in Ghent, Belgium.

Established before the state of Belgium itself, the university was founded by the Dutch King William I in 1817, when the ...

and Plant Genetic Systems, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

) discovered the gene transfer mechanism between ''Agrobacterium'' and plants, which resulted in the development of methods to alter the bacterium into an efficient delivery system for genetic engineering in plants. The plasmid T-DNA that is transferred to the plant is an ideal vehicle for genetic engineering. This is done by cloning a desired gene sequence into T-DNA binary vectors that will be used to deliver a sequence of interest into eukaryotic cells. Soon it was widely agreed that Asilomar like protections were needed in plant technologies as well. This process has been performed using firefly luciferase gene to produce glowing plants. This luminescence

Luminescence is spontaneous emission of light by a substance not resulting from heat; or "cold light".

It is thus a form of cold-body radiation. It can be caused by chemical reactions, electrical energy, subatomic motions or stress on a crys ...

has been a useful device in the study of plant chloroplast function and as a reporter gene

In molecular biology, a reporter gene (often simply reporter) is a gene that researchers attach to a regulatory sequence of another gene of interest in bacteria, cell culture, animals or plants. Such genes are called reporters because the charac ...

. It is also possible to transform '' Arabidopsis thaliana'' by dipping flowers into a broth of ''Agrobacterium'': the seed produced will be transgenic

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

. Under laboratory conditions, the T-DNA has also been transferred to human cells, demonstrating the diversity of insertion application.

The mechanism by which ''Agrobacterium'' inserts materials into the host cell is by a type IV secretion system The bacterial type IV secretion system, also known as the type IV secretion system or the T4SS, is a secretion protein complex found in gram negative bacteria, gram positive bacteria, and archaea. It is able to transport proteins and DNA across t ...

which is very similar to mechanisms used by pathogens

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

to insert materials (usually proteins) into human cells by type III secretion. It also employs a type of signaling conserved in many Gram-negative bacteria called quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signalling (QS) is the ability to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation. As one example, QS enables bacteria to restrict the expression of specific genes to the high cell densities at ...

. This makes ''Agrobacterium'' an important topic of medical research, as well .

Natural genetic transformation

Natural genetic transformation inbacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

is a sexual process involving the transfer of DNA from one cell to another through the intervening medium, and the integration of the donor sequence into the recipient genome by homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

. ''A. tumefaciens'' can undergo natural transformation in soil without any specific physical or chemical treatment.

Disease cycle

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' overwinters in infested soils. ''Agrobacterium'' species live predominantly saprophytic lifestyles, so its common even for plant-parasitic species of this genus to survive in the soil for lengthy periods of time, even without host plant presence. When there is a host plant present, however, the bacteria enter the plant tissue via recent wounds or natural openings of roots or stems near the ground. These wounds may be caused by cultural practices, grafting, insects, etc. Once the bacteria have entered the plant, they occur intercellularly and stimulate surrounding tissue to proliferate due to cell transformation. ''Agrobacterium'' performs this control by inserting the plasmid T-DNA into the plant's genome. See above for more details about the process of plasmid DNA insertion into the host genome. Excess growth of the plant tissue leads to gall formation on the stem and roots. These tumors exert significant pressure on the surrounding plant tissue, which causes this tissue to become crushed and/or distorted. The crushed vessels lead to reduced water flow in the xylem. Young tumors are soft and therefore vulnerable to secondary invasion by insects and saprophytic microorganisms. This secondary invasion causes the breakdown of the peripheral cell layers as well as tumor discoloration due to decay. Breakdown of the soft tissue leads to release of the ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' into the soil allowing it to restart the disease process with a new host plant.

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' overwinters in infested soils. ''Agrobacterium'' species live predominantly saprophytic lifestyles, so its common even for plant-parasitic species of this genus to survive in the soil for lengthy periods of time, even without host plant presence. When there is a host plant present, however, the bacteria enter the plant tissue via recent wounds or natural openings of roots or stems near the ground. These wounds may be caused by cultural practices, grafting, insects, etc. Once the bacteria have entered the plant, they occur intercellularly and stimulate surrounding tissue to proliferate due to cell transformation. ''Agrobacterium'' performs this control by inserting the plasmid T-DNA into the plant's genome. See above for more details about the process of plasmid DNA insertion into the host genome. Excess growth of the plant tissue leads to gall formation on the stem and roots. These tumors exert significant pressure on the surrounding plant tissue, which causes this tissue to become crushed and/or distorted. The crushed vessels lead to reduced water flow in the xylem. Young tumors are soft and therefore vulnerable to secondary invasion by insects and saprophytic microorganisms. This secondary invasion causes the breakdown of the peripheral cell layers as well as tumor discoloration due to decay. Breakdown of the soft tissue leads to release of the ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' into the soil allowing it to restart the disease process with a new host plant.

Disease management

Crown gall disease caused by ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' can be controlled by using various methods. The best way to control this disease is to take preventative measures, such as sterilizing pruning tools so as to avoid infecting new plants. Performing mandatory inspections of nursery stock and rejecting infected plants as well as not planting susceptible plants in infected fields are also valuable practices. Avoiding wounding the crowns/roots of the plants during cultivation is important for preventing disease. In horticultural techniques in which multiple plants are joined to grow as one, such as budding and grafting these techniques lead to plant wounds. Wounds are the primary location of bacterial entry into the host plant. Therefore, it is advisable to perform these techniques during times of the year when ''Agrobacteria'' are not active. Control of root-chewing insects is also helpful to reduce levels of infection, since these insects cause wounds (aka bacterial entryways) in the plant roots. It is recommended that infected plant material be burned rather than placed in a compost pile due to the bacteria's ability to live in the soil for many years. Biological control methods are also utilized in managing this disease. During the 1970s and 1980s, a common practice for treating germinated seeds, seedlings, and rootstock was to soak them in a suspension of K84. K84 is composed of ''A. radiobacter,'' which is a species related to ''A. tumefaciens'' but is not pathogenic. K84 produces a bacteriocin (agrocin 84) which is an antibiotic specific against related bacteria, including ''A. tumefaciens''. This method, which was successful at controlling the disease on a commercial scale, had the risk of K84 transferring its resistance gene to the pathogenic ''Agrobacteria.'' Thus, in the 1990s, the use of a genetically engineering strain of K84, known as K-1026, was created. This strain is just as successful in controlling crown gall as K84 without the caveat of resistance gene transfer.Environment

Host, environment, and pathogen are extremely important concepts in regards to plant pathology. ''Agrobacteria'' have the widest host range of any plant pathogen, so the main factor to take into consideration in the case of crown gall is environment. There are various conditions and factors that make for a conducive environment for ''A. tumefaciens'' when infecting its various hosts. The bacterium can't penetrate the host plant without an entry point such as a wound. Factors leading to wounds in plants include cultural practices, grafting, freezing injury, growth cracks, soil insects, and other animals in the environment causing damage to the plant. Consequently, in exceptionally harsh winters, it is common to have an increased incidence of crown gall due to the weather-related damage. Along with this, there are methods of mediating infection of the host plant. For example, nematodes can act as a vector to introduce ''Agrobacterium'' into plant roots. More specifically, the root parasitic nematodes damage the plant cell, creating a wound for the bacteria to enter through. Finally, temperature is a factor when considering ''A. tumefaciens'' infection. The optimal temperature for crown gall formation due to this bacterium is 22 °C because of the thermosensitivity of T-DNA transfer. Tumor formation is significantly reduced at higher temperature conditions.

Host, environment, and pathogen are extremely important concepts in regards to plant pathology. ''Agrobacteria'' have the widest host range of any plant pathogen, so the main factor to take into consideration in the case of crown gall is environment. There are various conditions and factors that make for a conducive environment for ''A. tumefaciens'' when infecting its various hosts. The bacterium can't penetrate the host plant without an entry point such as a wound. Factors leading to wounds in plants include cultural practices, grafting, freezing injury, growth cracks, soil insects, and other animals in the environment causing damage to the plant. Consequently, in exceptionally harsh winters, it is common to have an increased incidence of crown gall due to the weather-related damage. Along with this, there are methods of mediating infection of the host plant. For example, nematodes can act as a vector to introduce ''Agrobacterium'' into plant roots. More specifically, the root parasitic nematodes damage the plant cell, creating a wound for the bacteria to enter through. Finally, temperature is a factor when considering ''A. tumefaciens'' infection. The optimal temperature for crown gall formation due to this bacterium is 22 °C because of the thermosensitivity of T-DNA transfer. Tumor formation is significantly reduced at higher temperature conditions.

See also

* '' suhB''References

Further reading

* * * *External links

*"''Agrobacterium fabrum''" C58 Genome Page

nbsp;— as sequenced by Cereon Genomics/University of Richmond {{Authority control Gram-negative bacteria Bacterial plant pathogens and diseases Bacterial grape diseases Bacteria described in 1907 Rhizobiaceae