Republic of Central Lithuania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Republic of Central Lithuania ( pl, Republika Litwy Środkowej, ), commonly known as the Central Lithuania, and the Middle Lithuania ( pl, Litwa Środkowa, , be, Сярэдняя Літва, translit=Siaredniaja Litva), was an unrecognized short-lived puppet republic of

The ethnic composition of the area has long been disputed, since

The ethnic composition of the area has long been disputed, since

At the end of World War I, the area of the former

At the end of World War I, the area of the former

Peace talks were held under the auspice of the

Peace talks were held under the auspice of the  The talks came to a halt when Poland demanded that a delegation from Central Lithuania (boycotted by Lithuania) be invited to

The talks came to a halt when Poland demanded that a delegation from Central Lithuania (boycotted by Lithuania) be invited to

After the talks in Brussels failed, the tensions in the area grew. The most important issue was the huge army Central Lithuania fielded (27,000). General

After the talks in Brussels failed, the tensions in the area grew. The most important issue was the huge army Central Lithuania fielded (27,000). General

Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary in the 4th decade of the 19th century

* ttp://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/lt-cent.html State symbols of Central Lithuania

Repatriation and resettlement of Ethnic Poles

From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilnius-Wilno 1900–1925

*

Kampf um Wilna – historische Rechte und demographische Argumente

Mixed ethnic groups around Wilno / Vilnius during inter-war period

after

Stamps of ROC

*

A. Srebrakowski, Sejm Wileński 1922 roku. Idea i jej realizacja, Wrocław 1993

*

A. Srebrakowski, Stosunek mniejszości narodowych Litwy Środkowej wobec wyborów do Sejmu Wileńskiego

*

A. Srebrakowski, Konflik polsko_litewski na tle wydarzeń roku 1920

{{DEFAULTSORT:Central Lithuania, Republic of Historical regions in Lithuania Former countries in Europe 1920s in Lithuania Post–Russian Empire states Lithuania–Poland relations States and territories established in 1920 States and territories disestablished in 1922 1920 establishments in Europe 1920 establishments in Belarus 1920 establishments in Lithuania 1920 establishments in Poland 1922 disestablishments in Europe 1922 disestablishments in Belarus 1922 disestablishments in Lithuania 1922 disestablishments in Poland Former countries of the interwar period

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, that existed from 1920 to 1922. It was founded on 12 October 1920, after Żeligowski's Mutiny

Żeligowski's Mutiny ( pl, bunt Żeligowskiego, also ''żeligiada'', lt, Želigovskio maištas) was a Polish false flag operation led by General Lucjan Żeligowski in October 1920, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuan ...

, when soldiers of the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stret ...

, mainly the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Infantry Division under Lucjan Żeligowski

Lucjan Żeligowski (; 17 October 1865 – 9 July 1947) was a Polish-Lithuanian general, politician, military commander and veteran of World War I, the Polish-Soviet War and World War II. He is mostly remembered for his role in Żeligowski's M ...

, fully supported by the Polish air force, cavalry and artillery, attacked Lithuania. It was incorporated into Poland on 18 April 1922.

Centered around Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, the historical capital of Lithuania, for 18 months the entity served as a buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

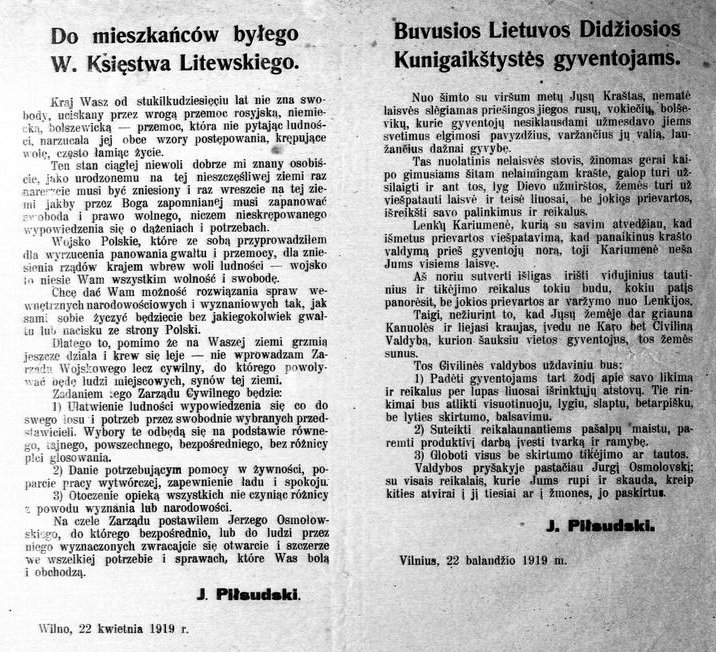

between Poland, upon which it depended, and Lithuania, which claimed the area. This territory was a means of pressure on Lithuania as Poland tried to trade the Lithuanian capital to Lithuania in return for the dependence of re-emerged Lithuania (proposal of union between the two states) or surrender to Poland (proposal of autonomy for Lithuania within Polish borders). After a variety of delays, a disputed election took place on 8 January 1922, and the territory was annexed to Poland. Initially, the Polish government denied that it was responsible for the false flag action, but the Polish leader Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

subsequently acknowledged that he personally ordered Żeligowski to pretend that he was acting as a mutinous Polish officer.

The Polish–Lithuanian borders in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, while recognized by the Conference of Ambassadors

The Conference of Ambassadors of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers was an inter-allied organization of the Entente in the period following the end of World War I. Formed in Paris in January 1920 it became a successor of the Supreme War ...

of the Entente

Entente, meaning a diplomatic "understanding", may refer to a number of agreements:

History

* Entente (alliance), a type of treaty or military alliance where the signatories promise to consult each other or to cooperate with each other in case o ...

and the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, were not recognized by Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

-based Republic of Lithuania

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

until the Polish ultimatum of 1938. In 1931 an international court in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

stated that the Polish seizure of the city had been a violation of international law, but there were no significant political repercussions.

History

Following thepartitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, most of the lands that formerly constituted the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Li ...

were annexed by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. The Imperial government increasingly pursued a policy of Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

of the newly acquired lands, which escalated after the failed January Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

of 1864. The discrimination against local inhabitants included restrictions and outright bans on the usage of the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

, Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

(see Lithuanian press ban

The Lithuanian press ban ( lt, spaudos draudimas) was a ban on all Lithuanian language publications printed in the Latin alphabet in force from 1865 to 1904 within the Russian Empire, which controlled Lithuania proper at the time. Lithuanian-lan ...

), Belarusian

Belarusian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Belarus

* Belarusians, people from Belarus, or of Belarusian descent

* A citizen of Belarus, see Demographics of Belarus

* Belarusian language

* Belarusian culture

* Belarusian cuisine

* Byelor ...

, and Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

(see Valuyev circular

The Valuev Circular (russian: Валуевский циркуляр, Valuyevskiy tsirkulyar; uk, Валуєвський циркуляр, Valuievs'kyi tsyrkuliar) of 18 July 1863 was a decree (ukaz) issued by Pyotr Valuev (Valuyev), Minister of I ...

) languages. These measures, however, had limited effects on the Polonisation

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

effort undertaken by the Polish patriotic leadership of the Vilnius educational district. A similar effort was pursued during the 19th century Lithuanian National Revival

The Lithuanian National Revival, alternatively the Lithuanian National Awakening or Lithuanian nationalism ( lt, Lietuvių tautinis atgimimas), was a period of the history of Lithuania in the 19th century at the time when a major part of Lithuanian ...

, which sought to distance itself from both Polish and Russian influences.

census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

es from that time and place are often considered unreliable. According to the first census of the Russian Empire in 1897, known to have been intentionally falsified, the population of the Vilna Governorate

The Vilna Governorate (1795–1915; also known as Lithuania-Vilnius Governorate from 1801 until 1840; russian: Виленская губерния, ''Vilenskaya guberniya'', lt, Vilniaus gubernija, pl, gubernia wileńska) or Government of V ...

was distributed as follows: Belarusians

, native_name_lang = be

, pop = 9.5–10 million

, image =

, caption =

, popplace = 7.99 million

, region1 =

, pop1 = 600,000–768,000

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

at 56.1% (including Roman Catholics), Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Uni ...

at 17.6%, Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s at 12.7%, Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

at 8.2%, Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

at 4.9%, Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

at 0.2%, Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

at 0.1%, Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

at 0.1%, and 'Others' at 0.1% as well.

The 1916 German census of the in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Vilnius Region

Vilnius Region is the territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time.

The territory ...

(published in 1919), however, reported strikingly different numbers. Poles at 58.0%, Lithuanians at 18.5%, Jews at 14.7%, Belarusians at 6.4%, Russians at 1.2%, and 'Other' at 1.2%.

Both censuses had encountered difficulties in the attempt to categorise their subjects. Ethnographers

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

in the 1890s were often confronted with those who described themselves as both Lithuanians and Poles. According to a German census analyst, "Objectively determining conditions of nationality comes up against the greatest difficulties."

Aftermath of World War I

In theaftermath of the First World War

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

, both Poland and Lithuania regained independence. The conflict between them soon arose as both Lithuania and Poland claimed Vilnius (known in Polish as Wilno) region.

Demographically, the main groups inhabiting Vilnius were Poles and Jews, with Lithuanians constituting a small fraction of the total population (2.0%–2.6%, according to the Russian census of 1897 and the German census of 1916). The Lithuanians nonetheless believed that their historical claim to Vilnius (former capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Li ...

) had precedence and refused to recognize any Polish claims to the city and the surrounding area.

While Poland under Józef Piłsudski attempted to create a Polish-led federation in the area that would include a number of ethnically non-Polish territories (Międzymorze

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

), Lithuania strove to create a fully independent state that would include the Vilnius region

Vilnius Region is the territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time.

The territory ...

. Two early 20th-century censuses indicated that Lithuanian speakers, whose language in the second half of the 19th century was suppressed by the Russian policies and had unfavourable conditions within the Catholic church, became a minority in the region. Based on this, Lithuanian authorities argued that the majority of inhabitants living there, even if they at the time did not speak Lithuanian, were thus Polonized

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

(or Russified

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

) Lithuanians.

Further complicating the situation, there were two Polish factions with quite different views on creation of the modern state in Poland. One party, led by Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

, saw modern Poland as an ethnic state, another, led by Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

, wished to rebuild the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Both parties were determined to take the Poles of Vilnius into the new state. Piłsudski attempted to rebuild the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in a canton structure, as part of the Międzymorze

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

federation:

*Lithuania of Kaunas with Lithuanian language

*Lithuania of Vilnius or Central Lithuania with Polish language

*Lithuania of Minsk with Belarusian language

Eventually, Piłsudski's plan failed; it was opposed both by the Lithuanian government and by the Dmowski faction in Poland. Stanisław Grabski

Stanisław Grabski (; 5 April 1871 – 6 May 1949) was a Polish economist and politician associated with the National Democracy political camp. As the top Polish negotiator during the Peace of Riga talks in 1921, Grabski greatly influenced the f ...

, representative of Dmowski's faction, was in charge of the Treaty of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War.

...

negotiations with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, in which they rejected the Soviet offer of territories needed for the Minsk canton (Dmowski preferred Poland that would be smaller, but with higher percentage of ethnic Poles). The inclusion of territories predominant with non-Poles would have weakened support for Dmowski.

Polish–Lithuanian War

At the end of World War I, the area of the former

At the end of World War I, the area of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Li ...

was divided between the Republic of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, the Belarusian People's Republic

The Belarusian People's Republic (BNR; be, Беларуская Народная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Narodnaja Respublika, ), or Belarusian Democratic Republic, was a state proclaimed by the Council of the Belarusian Democratic R ...

, and the Republic of Lithuania

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

. Following the start of the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

, during the next two years, the control of Vilnius and its environs changed frequently. In 1919 the territory was briefly occupied by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, which defeated the local self-defense units, but shortly afterwards the Russians were pushed back by the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stret ...

. 1920 saw the Vilnius region occupied by the Red Army for the second time. However, when the Red Army was defeated in the Battle of Warsaw, the Soviets made the decision to hand the city back over to Lithuania. The Polish–Lithuanian War

The Polish–Lithuanian War (in Polish historiography, Polish–Lithuanian Conflict) was an undeclared war between newly-independent Lithuania and Poland following World War I, which happened mainly, but not only, in the Vilnius and Suwałki regi ...

erupted when Lithuania and Poland clashed over the Suvalkai Region on August 26, 1920. The League of Nations intervened and arranged negotiations in Suwałki

Suwałki ( lt, Suvalkai; yi, סואוואַלק) is a city in northeastern Poland with a population of 69,206 (2021). It is the capital of Suwałki County and one of the most important centers of commerce in the Podlaskie Voivodeship. Suwałki i ...

. The League negotiated a cease-fire, signed on October 7, 1920, placing the city of Vilnius in Lithuania. The Suwałki Agreement

The Suwałki Agreement, Treaty of Suvalkai, or Suwalki Treaty ( pl, Umowa suwalska, lt, Suvalkų sutartis) was an agreement signed in the town of Suwałki between Poland and Lithuania on October 7, 1920. It was registered in the '' League of N ...

was to have taken effect at 12:00 on October 10, 1920.

The Lithuanian authorities entered Vilna in late August 1920. The Grinius cabinet rejected the proposal to hold a plebiscite to confirm the will of the region's inhabitants. His declaration was promptly accepted by the Seimas, for the percentage of Lithuanian population in Vilna was very small. On October 8, 1920, General Lucjan Żeligowski

Lucjan Żeligowski (; 17 October 1865 – 9 July 1947) was a Polish-Lithuanian general, politician, military commander and veteran of World War I, the Polish-Soviet War and World War II. He is mostly remembered for his role in Żeligowski's M ...

and the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Infantry Division

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

numbering around 14,000 men, with local self-defense, launched the Żeligowski's Mutiny

Żeligowski's Mutiny ( pl, bunt Żeligowskiego, also ''żeligiada'', lt, Želigovskio maištas) was a Polish false flag operation led by General Lucjan Żeligowski in October 1920, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuan ...

and engaged the Lithuanian 4th Infantry Regiment which promptly retreated. Upon the Polish advance, on October 8, the Lithuanian government left the city for Kaunas, and during withdrawal, meticulously destroyed telephone lines and rail between the two cities, which remained severed for a generation. Żeligowski entered Vilna on October 9, 1920, to enthusiastic cheers of the overwhelmingly Polish population of the city. The French and the British delegation decided to leave the matter in the hands of the League of Nations. On October 27, while the Żeligowski's campaign still continued outside Vilna, the League called for a popular referendum in the disputed area, which was again rejected by the Lithuanian representation. Poland disclaimed all responsibility for the action, maintaining that Żeligowski had acted entirely on his own initiative. This version of the event was redefined in August 1923 when Piłsudski, speaking in public at a Vilnius theater, stated that the attack was undertaken by his direct order. Żeligowski, a native to Lithuania, proclaimed a new bilingual state, the Republic of Central Lithuania (''Litwa Środkowa''). According to historian Jerzy J. Lerski, it was a "puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its o ...

" which the Lithuanian Republic refused to recognize.

The seat of Lithuanian government moved to Lithuania's second-largest city, Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

. Armed conflicts between Kaunas and Central Lithuania continued for a few weeks, but neither side could gain a significant advantage. Due to the mediation efforts of the League of Nations, a new ceasefire was signed on November 21 and a truce six days later.

Founding of the Republic of Central Lithuania

On October 12, 1920, Żeligowski announced the creation of aprovisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

. Soon the courts and the police were formed by his decree of January 7, 1921, and the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

of Central Lithuania were granted to all people who lived in the area on January 1, 1919, or for five years prior to August 1, 1914. The symbols of the state were a red flag with Polish White Eagle and Lithuanian Vytis

The coat of arms of Lithuania consists of a mounted armoured knight holding a sword and shield, known as (). Since the early 15th century, it has been Lithuania's official coat of arms and is one of the oldest European coats of arms. It is als ...

. Its coat of arms was a mixture of Polish, Lithuanian and Vilnian symbols and resembled the Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Coat of Arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was the symbol of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, representing the union of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom and Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Modern reconstruction

File:Coat of Arms ...

.

Extensive diplomatic negotiations continued behind the scenes. Lithuania proposed creating a confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

of Baltic Western Lithuania (with Lithuanian as an official language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

) and Central Lithuania (with Polish as an official language). Poland added the condition that the new state must be also federated with Poland, pursuing Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

's goal of creating the Międzymorze

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

Federation. Lithuanians rejected this condition. With nationalistic sentiments rising all over Europe, many Lithuanians were afraid that such a federation, resembling the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

from centuries ago, would be a threat to Lithuanian culture

Culture of Lithuania combines an indigenous heritage, represented by the unique Lithuanian language, with Nordic cultural aspects and Christian traditions resulting from historical ties with Poland. Although linguistic resemblances represent st ...

, as during the Commonwealth times many of the Lithuanian nobility was Polonized

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

.

General elections in Central Lithuania were decreed to take place on January 9, 1921, and the regulations governing this election were to be issued prior to November 28, 1920. However, due to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

mediation, and the Lithuanian boycott of the voting, the elections were postponed.Saulius A. Suziedelis, ''Historical Dictionary of Lithuania'', Scarecrow Press, 2011; , pg. 78: “The elections of the Central Lithuania (...) were boycotted by much of the non-Polish population”.

Mediation

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. The initial agreement was signed by both sides on November 29, 1920, and the talks started on March 3, 1921. The League of Nations considered the Polish proposal of a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on the future of Central Lithuania. As a compromise, the so-called "Hymans' plan" was proposed (named after Paul Hymans

Paul Louis Adrien Henri Hymans (23 March 1865 – 8 March 1941), was a Belgian politician associated with the Liberal Party. He was the second president of the League of Nations and served again as its president in 1932–1933.

Life

Hymans was ...

). The plan consisted of 15 points, among them were:

*Both sides guarantee each other's independence.

*Central Lithuania is incorporated into the Federation of Lithuania, composed of two cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, t ...

: Lithuanian-inhabited Samogitia

Samogitia or Žemaitija ( Samogitian: ''Žemaitėjė''; see below for alternative and historical names) is one of the five cultural regions of Lithuania and formerly one of the two core administrative divisions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and multi-ethnic (Belarusian, Tatar, Polish, Jewish and Lithuanian) Vilnius area. Both cantons will have separate governments, parliaments, official language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

s and a common federative capital in Vilnius.

*Lithuanian and Polish governments will create interstate commissions on both foreign affairs, trade and industry measures and local policies.

*Poland and Lithuania will sign a defensive alliance treaty.

*Poland will gain usage of ports in Lithuania.

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

. On the other hand, Lithuanians demanded that the troops in Central Lithuania be relocated behind the line drawn by the October 7, 1920 cease-fire agreement, while Hymans' proposal left Vilnius in Polish hands, which was unacceptable to Lithuania.

A new plan was presented to the governments of Lithuania and Poland in September 1921. It was basically a modification of "Hymans' plan", with the difference that the Klaipėda Region

The Klaipėda Region ( lt, Klaipėdos kraštas) or Memel Territory (german: Memelland or ''Memelgebiet'') was defined by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles in 1920 and refers to the northernmost part of the German province of East Prussia, when as ...

(the area in East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

north of the Neman River

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ...

) was to be incorporated into Lithuania. However, both Poland and Lithuania openly criticized this revised plan and finally this turn of talks came to a halt as well.

Resolution

After the talks in Brussels failed, the tensions in the area grew. The most important issue was the huge army Central Lithuania fielded (27,000). General

After the talks in Brussels failed, the tensions in the area grew. The most important issue was the huge army Central Lithuania fielded (27,000). General Lucjan Żeligowski

Lucjan Żeligowski (; 17 October 1865 – 9 July 1947) was a Polish-Lithuanian general, politician, military commander and veteran of World War I, the Polish-Soviet War and World War II. He is mostly remembered for his role in Żeligowski's M ...

decided to pass the power to the civil authorities and confirmed the date of the elections (January 8, 1922). There was a significant electioneering propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

campaign as Poles tried to win the support of other ethnic groups present in the area. The Polish government was also accused of various strong-arm policies (like the closing of Lithuanian newspapers or election violations like not asking for a valid document from a voter). The elections were boycotted by Lithuanians, most of the Jews and some Belarusians. Poles were the only major ethnic group out of which the majority of people voted.

The elections were not recognized by Lithuania. Polish factions, which gained control over the parliament (Sejm) of the Republic (the Sejm of Central Lithuania

Sejm of Central Lithuania ( pl, Sejm Litwy Środkowej), also known as the Vilnius Sejm, or Wilno Sejm ( pl, Sejm Wileński) or the Adjudicating Sejm ( pl, Sejm Orzekający), was the parliament of the short-lived state of Central Lithuania. Formed ...

), on February 20 passed the request of incorporation into Poland. The request was accepted by the Polish Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

on March 22, 1922.

All of the Republic's territory was eventually incorporated into the newly formed Wilno Voivodeship. Lithuania declined to accept the Polish authority over the area. Instead, it continued to treat the so-called Vilnius Region

Vilnius Region is the territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time.

The territory ...

as part of its own territory and the city itself as its constitutional capital, with Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

being only a temporary seat of government. The dispute over the Vilnius region resulted in much tensions in the Polish–Lithuanian relations in the interwar

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relativel ...

period.

Aftermath

Alfred Erich Senn

Alfred Erich Senn (April 12, 1932 – March 8, 2016) was a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Senn was born in Madison, Wisconsin, to Swiss philologist and lexicographer, . His father taught at the University of Li ...

noted that if Poland had not prevailed in the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

, Lithuania would have been invaded by the Soviets, and would never have experienced two decades of independence. Despite the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty

The Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, also known as the Moscow Peace Treaty, was signed between Lithuania and Soviet Russia on July 12, 1920. In exchange for Lithuania's neutrality and permission to move its troops in the territory that was reco ...

of 1920, Lithuania was very close to being invaded by the Soviets in summer 1920 and being forcibly incorporated into that state, and only the Polish victory derailed this plan.

After the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

and the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subse ...

in 1939, Vilnius and its surroundings of up to 30 kilometres were given to Lithuania in accordance with the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty

The Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty ( lt, Lietuvos-Sovietų Sąjungos savitarpio pagalbos sutartis) was a bilateral treaty signed between the Soviet Union and Lithuania on October 10, 1939. According to provisions outlined in the tre ...

of October 10, 1939, and Vilnius again became the capital of Lithuania. However, in 1940, Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union, forcing the country to become the Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

. Since the restoration of Lithuanian independence in 1991, the city's status as Lithuania's capital has been internationally recognized.

See also

*Army of Central Lithuania

The Army of Central Lithuania was the armed forces of the state of Central Lithuania proclaimed by General Lucjan Żeligowski on October 12, 1920.

With the announcement by General Lucjan Żeligowski of the establishment of Central Lithuania, ...

* History of Vilnius

The city of Vilnius, the capital and largest city of Lithuania, has undergone a diverse history since it was first settled in the Stone Age. Vilnius was the head of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania right until 1795, even during the Polish–Lithuania ...

* Vilnius Voivodeship

The Vilnius Voivodeship ( la, Palatinatus Vilnensis, lt, Vilniaus vaivadija, pl, województwo wileńskie, be, Віленскае ваяводства) was one of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania's voivodeships, which existed from the voivodeship's ...

* Polish National-Territorial Region

Polish autonomy in the Vilnius Region was an idea developed among the Polish minority in Lithuania in 1988, when that country was regaining its independence from the Soviet Union.

As a result of perestroika, under the influence of their own nation ...

* The 1922 Republic of Central Lithuania general election

The general election in the Republic of Central Lithuania was an election to the Vilnius Sejm (parliament) of the Polish-dominated Republic of Central Lithuania on 8 January 1922. The new parliament was intended to formally legalize incorporation ...

* List of sovereign states in 1922

References

External links

Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary in the 4th decade of the 19th century

* ttp://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/lt-cent.html State symbols of Central Lithuania

Repatriation and resettlement of Ethnic Poles

From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilnius-Wilno 1900–1925

*

Kampf um Wilna – historische Rechte und demographische Argumente

Mixed ethnic groups around Wilno / Vilnius during inter-war period

after

Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor at ...

, ''God's Playground: A History of Poland: Volume II, 1795 to the Present''; Columbia University Press: 1982.

Stamps of ROC

*

A. Srebrakowski, Sejm Wileński 1922 roku. Idea i jej realizacja, Wrocław 1993

*

A. Srebrakowski, Stosunek mniejszości narodowych Litwy Środkowej wobec wyborów do Sejmu Wileńskiego

*

A. Srebrakowski, Konflik polsko_litewski na tle wydarzeń roku 1920

{{DEFAULTSORT:Central Lithuania, Republic of Historical regions in Lithuania Former countries in Europe 1920s in Lithuania Post–Russian Empire states Lithuania–Poland relations States and territories established in 1920 States and territories disestablished in 1922 1920 establishments in Europe 1920 establishments in Belarus 1920 establishments in Lithuania 1920 establishments in Poland 1922 disestablishments in Europe 1922 disestablishments in Belarus 1922 disestablishments in Lithuania 1922 disestablishments in Poland Former countries of the interwar period