Regulamentul Organic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual nature of the document; however, the singular version is usually preferred. The text was originally written in French, submitted to the approval of the

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual nature of the document; however, the singular version is usually preferred. The text was originally written in French, submitted to the approval of the

In the last decades of the 18th century, the growing strategic importance of the region brought about the establishment of

In the last decades of the 18th century, the growing strategic importance of the region brought about the establishment of

The first reigns through locals— Ioniță Sandu Sturdza as Prince of Moldavia and

The first reigns through locals— Ioniță Sandu Sturdza as Prince of Moldavia and

The post-Adrianople state of affairs was perceived by many of the inhabitants of Wallachia and Moldavia as exceptionally abusive, given that Russia confiscated both of the Principalities' treasuries, and that Zheltukhin used his position to interfere in the proceedings of the commission, nominated his own choice of members, and silenced all opposition by having anti-Russian boyars expelled from the countries (including, notably, Iancu Văcărescu, a member of the Wallachian ''

The post-Adrianople state of affairs was perceived by many of the inhabitants of Wallachia and Moldavia as exceptionally abusive, given that Russia confiscated both of the Principalities' treasuries, and that Zheltukhin used his position to interfere in the proceedings of the commission, nominated his own choice of members, and silenced all opposition by having anti-Russian boyars expelled from the countries (including, notably, Iancu Văcărescu, a member of the Wallachian '' Each National Assembly (approximate translation of ''Adunarea Obștească''), inaugurated in 1831–2, was a legislature itself under the control of high-ranking boyars, comprising 35 (in Moldavia) or 42 members (in Wallachia), voted into office by no more than 3,000 electors in each state; the judiciary was, for the very first time, removed from the control of ''hospodars''.Hitchins, pp. 204–5.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, pp. 51–2.Detailed membership of the Assembly in Wallachia: the Metropolitan of Hungro-Wallachia, Metropolitan bishop was president, and all other bishops were members, together with 20 high-ranking boyars and 18 other boyars (Hitchins, p. 204). In effect, the ''Regulament'' confirmed earlier steps leading to the eventual separation of church and state, and, although Romanian Orthodox Church, Orthodox church authorities were confirmed a privileged position and a political say, the religious institution was closely supervised by the government (with the establishment of a quasi-salary expense).Hitchins, p. 207.

A tax reform, fiscal reform ensued, with the creation of a Tax per head, poll tax (calculated per family), the elimination of most indirect taxes, annual state budgets (approved by the Assemblies) and the introduction of a civil list in place of the ''hospodars personal treasuries. New methods of bookkeeping were regulated, and the creation of national banks was projected, but, like the adoption of national fixed currency, fixed currencies, was never implemented.

According to the historian Nicolae Iorga, "The [boyar] oligarchy was appeased [by the ''Regulaments adoption]: a beautifully harmonious modern form had veiled the old Romania in the Middle Ages, medieval structure…. The ''bourgeoisie''… held no influence. As for the peasant, he lacked even the right to administer his own commune in Romania, commune, he was not even allowed to vote for an Assembly deemed, as if in jest, «national»." Nevertheless, conservative boyars remained suspicious of Russian tutelage, and several expressed their fear that the regime was a step leading to the creation of a regional ''guberniya'' for the Russian Empire. Their mistrust was, in time, reciprocated by Russia, who relied on ''hospodars'' and the direct intervention of its consuls to push further reforms.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 52. Kiselyov himself voiced a plan for the region's annexation to Russia, but the request was dismissed by his superiors.

Each National Assembly (approximate translation of ''Adunarea Obștească''), inaugurated in 1831–2, was a legislature itself under the control of high-ranking boyars, comprising 35 (in Moldavia) or 42 members (in Wallachia), voted into office by no more than 3,000 electors in each state; the judiciary was, for the very first time, removed from the control of ''hospodars''.Hitchins, pp. 204–5.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, pp. 51–2.Detailed membership of the Assembly in Wallachia: the Metropolitan of Hungro-Wallachia, Metropolitan bishop was president, and all other bishops were members, together with 20 high-ranking boyars and 18 other boyars (Hitchins, p. 204). In effect, the ''Regulament'' confirmed earlier steps leading to the eventual separation of church and state, and, although Romanian Orthodox Church, Orthodox church authorities were confirmed a privileged position and a political say, the religious institution was closely supervised by the government (with the establishment of a quasi-salary expense).Hitchins, p. 207.

A tax reform, fiscal reform ensued, with the creation of a Tax per head, poll tax (calculated per family), the elimination of most indirect taxes, annual state budgets (approved by the Assemblies) and the introduction of a civil list in place of the ''hospodars personal treasuries. New methods of bookkeeping were regulated, and the creation of national banks was projected, but, like the adoption of national fixed currency, fixed currencies, was never implemented.

According to the historian Nicolae Iorga, "The [boyar] oligarchy was appeased [by the ''Regulaments adoption]: a beautifully harmonious modern form had veiled the old Romania in the Middle Ages, medieval structure…. The ''bourgeoisie''… held no influence. As for the peasant, he lacked even the right to administer his own commune in Romania, commune, he was not even allowed to vote for an Assembly deemed, as if in jest, «national»." Nevertheless, conservative boyars remained suspicious of Russian tutelage, and several expressed their fear that the regime was a step leading to the creation of a regional ''guberniya'' for the Russian Empire. Their mistrust was, in time, reciprocated by Russia, who relied on ''hospodars'' and the direct intervention of its consuls to push further reforms.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 52. Kiselyov himself voiced a plan for the region's annexation to Russia, but the request was dismissed by his superiors.

Beginning with the reformist administration of Kiselyov, the two countries experienced a series of profound changes, political, social, as well as cultural.

Despite underrepresentation in politics, the

Beginning with the reformist administration of Kiselyov, the two countries experienced a series of profound changes, political, social, as well as cultural.

Despite underrepresentation in politics, the  The Romanian middle class formed the basis for what was to become the Liberalism in Romania, liberal electorate, and accounted for the xenophobia, xenophobic discourse of the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Party during the latter's first decade of existence (between 1875 and World War I).Pavlowitch, Chapter 9, pp. 185–7

Urban development occurred at a very fast pace: overall, the urban population had doubled by 1850. Population estimates for

The Romanian middle class formed the basis for what was to become the Liberalism in Romania, liberal electorate, and accounted for the xenophobia, xenophobic discourse of the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Party during the latter's first decade of existence (between 1875 and World War I).Pavlowitch, Chapter 9, pp. 185–7

Urban development occurred at a very fast pace: overall, the urban population had doubled by 1850. Population estimates for

Vol. II, 1861 based on Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, 10th Edition and about 120,000 in 1859. For Iași, the capital of Moldavia, the estimates were 60,000 inhabitants for 1831, 70,000 for 1851, and about 65,000 for 1859. Brăila and Giurgiu, Danube ports returned to Wallachia by the Ottomans, as well as Moldavia's Galați, grew from the grain trade to become prosperous cities. Kiselyov, who had centered his administration on Bucharest, paid full attention to its development, improving its infrastructure and services and awarding it, together with all other cities and towns, a local administration (''see History of Bucharest''). Public works were carried out in the urban sphere, as well as in the massive expansion of the transport and communications system.Djuvara, p. 328.

The success of the grain trade was secured by a conservative take on property, which restricted the right of peasants to exploit for their own gain those plots of land they leased on boyar estate (land), estates (the ''Regulament'' allowed them to consume around 70% of the total harvest per plot leased, while boyars were allowed to use a third of their estate as they pleased, without any legal duty toward the neighbouring peasant workforce); at the same time, small properties, created after Constantine Mavrocordatos had abolished serfdom in the 1740s, proved less lucrative in the face of competition by large estates—boyars profited from the consequences, as more landowning peasants had to resort to leasing plots while still owing ''corvées'' to their lords. Confirmed by the ''Regulament'' at up to 12 days a year, the ''corvée'' was still less significant than in other parts of Europe; however, since peasants relied on cattle for alternative food supplies and financial resources, and pastures remained the exclusive property of boyars, they had to exchange right of use for more days of work in the respective boyar's benefit (as much as to equate the corresponding ''corvée'' requirements in Central European countries, without ever being enforced by laws).Djuvara, p. 327. Several laws of the period display a particular concern in limiting the right of peasants to evade ''corvées'' by paying their equivalent in currency, thus granting the boyars a workforce to match a steady growth in grain demands on foreign markets.

In respect to pasture access, the ''Regulament'' divided peasants into three wealth-based categories: ''fruntași'' ("foremost people"), who, by definition, owned 4 working animals and one or more cows (allowed to use around 4 hectares of pasture); ''mijlocași'' ("middle people")—two working animals and one cow (around 2 hectares); ''codași'' ("backward people")—people who owned no property, and not allowed the use of pastures.

At the same time, the major demography, demographic changes took their toll on the countryside. For the very first time, food supplies were no longer abundant in front of a population growth ensured by, among other causes, the effective measures taken against epidemics; rural–urban migration became a noticeable phenomenon, as did the relative increase in urbanization of traditional rural areas, with an explosion of settlements around established fairs.

The success of the grain trade was secured by a conservative take on property, which restricted the right of peasants to exploit for their own gain those plots of land they leased on boyar estate (land), estates (the ''Regulament'' allowed them to consume around 70% of the total harvest per plot leased, while boyars were allowed to use a third of their estate as they pleased, without any legal duty toward the neighbouring peasant workforce); at the same time, small properties, created after Constantine Mavrocordatos had abolished serfdom in the 1740s, proved less lucrative in the face of competition by large estates—boyars profited from the consequences, as more landowning peasants had to resort to leasing plots while still owing ''corvées'' to their lords. Confirmed by the ''Regulament'' at up to 12 days a year, the ''corvée'' was still less significant than in other parts of Europe; however, since peasants relied on cattle for alternative food supplies and financial resources, and pastures remained the exclusive property of boyars, they had to exchange right of use for more days of work in the respective boyar's benefit (as much as to equate the corresponding ''corvée'' requirements in Central European countries, without ever being enforced by laws).Djuvara, p. 327. Several laws of the period display a particular concern in limiting the right of peasants to evade ''corvées'' by paying their equivalent in currency, thus granting the boyars a workforce to match a steady growth in grain demands on foreign markets.

In respect to pasture access, the ''Regulament'' divided peasants into three wealth-based categories: ''fruntași'' ("foremost people"), who, by definition, owned 4 working animals and one or more cows (allowed to use around 4 hectares of pasture); ''mijlocași'' ("middle people")—two working animals and one cow (around 2 hectares); ''codași'' ("backward people")—people who owned no property, and not allowed the use of pastures.

At the same time, the major demography, demographic changes took their toll on the countryside. For the very first time, food supplies were no longer abundant in front of a population growth ensured by, among other causes, the effective measures taken against epidemics; rural–urban migration became a noticeable phenomenon, as did the relative increase in urbanization of traditional rural areas, with an explosion of settlements around established fairs.

These processes also ensured that Industrial Revolution, industrialization was minimal (although factory, factories had first been opened during the Phanariotes): most revenues came from a highly productive agriculture based on peasant labour, and were invested back into agricultural production. In parallel, hostility between agricultural workers and landowners mounted: after an increase in lawsuits involving leaseholders and the decrease in quality of ''corvée'' outputs, resistance, hardened by the examples of

These processes also ensured that Industrial Revolution, industrialization was minimal (although factory, factories had first been opened during the Phanariotes): most revenues came from a highly productive agriculture based on peasant labour, and were invested back into agricultural production. In parallel, hostility between agricultural workers and landowners mounted: after an increase in lawsuits involving leaseholders and the decrease in quality of ''corvée'' outputs, resistance, hardened by the examples of

Nationalist themes now included a preoccupation for the Origin of the Romanians, Latin origin of Romanians and the common (but since discarded) reference to the entire region as ''Dacia'' (first notable in the title of Mihail Kogălniceanu's ''Dacia Literară'', a short-lived Romantic literary magazine published in 1840). As a trans-border notion, ''Dacia'' also indicated a growth in Pan-Romanian sentiment—the latter had first been present in several boyar requests of the late 18th century, which had called for the union of the two Danubian Principalities under the protection of European powers (and, in some cases, under the rule of a foreign prince).Berindei, p. 8. To these was added the circulation of fake documents which were supposed to reflect the text of ''Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, Capitulations'' awarded by the

Nationalist themes now included a preoccupation for the Origin of the Romanians, Latin origin of Romanians and the common (but since discarded) reference to the entire region as ''Dacia'' (first notable in the title of Mihail Kogălniceanu's ''Dacia Literară'', a short-lived Romantic literary magazine published in 1840). As a trans-border notion, ''Dacia'' also indicated a growth in Pan-Romanian sentiment—the latter had first been present in several boyar requests of the late 18th century, which had called for the union of the two Danubian Principalities under the protection of European powers (and, in some cases, under the rule of a foreign prince).Berindei, p. 8. To these was added the circulation of fake documents which were supposed to reflect the text of ''Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, Capitulations'' awarded by the  The

The

In 1834, despite the founding documents' requirements, Russia and the Ottoman Empire agreed to appoint jointly the first two ''

In 1834, despite the founding documents' requirements, Russia and the Ottoman Empire agreed to appoint jointly the first two '' Immediately after the confirmation of the ''Regulament'', Russia had begun demanding that the two local Assemblies each vote an ''Additional Article'' (''Articol adițional'')—one preventing any modification of the texts without the common approval of the courts in Istanbul and Saint Petersburg.Djuvara, p. 329.Hitchins, p. 210. In Wallachia, the issue turned into scandal after the pressure for adoption mounted in 1834, and led to a four-year-long standstill, during which a nationalist group in the legislative body began working on its own project for a constitution, proclaiming the Russian

Immediately after the confirmation of the ''Regulament'', Russia had begun demanding that the two local Assemblies each vote an ''Additional Article'' (''Articol adițional'')—one preventing any modification of the texts without the common approval of the courts in Istanbul and Saint Petersburg.Djuvara, p. 329.Hitchins, p. 210. In Wallachia, the issue turned into scandal after the pressure for adoption mounted in 1834, and led to a four-year-long standstill, during which a nationalist group in the legislative body began working on its own project for a constitution, proclaiming the Russian

As the

As the

''Scrisori către Vasile Alecsandri''

: *

''Din vremea lui Caragea''

*

''Băltărețu''

*

''Bârzof''

* Constantin C. Giurescu, ''Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre'', Ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966 * Keith Hitchins, ''Românii, 1774–1866'', Humanitas, Bucharest, 1998 (translation of the English-language edition ''The Romanians, 1774–1866'', Oxford University Press, USA, 1996) * Nicolae Iorga, *

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains'' ''La Monarchie de juillet et les Roumains''

*

''Histoire des Roumains et de leur civilisation'' ''Renaissance roumaine au XIXe siècle avant l'union des Principautés''

* Stevan K. Pavlowitch, ''Istoria Balcanilor'', Polirom, Iași, 2002 (translation of the English-language edition ''A History of the Balkans 1804–1945'', Addison Wesley Longman Ltd., 1999) * Alecu Russo

''Amintiri''

{{in lang, ro

Moldavia Wallachia Law in the Russian Empire 1831 in law 1832 in law 1831 establishments in Europe 1858 disestablishments Defunct constitutions, Romania Crimean War Revolutions of 1848 Former Russian protectorates Legal history of Romania 1831 documents 1832 documents

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual nature of the document; however, the singular version is usually preferred. The text was originally written in French, submitted to the approval of the

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual nature of the document; however, the singular version is usually preferred. The text was originally written in French, submitted to the approval of the State Council of Imperial Russia

The State Council ( rus, Госуда́рственный сове́т, p=ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj sɐˈvʲet) was the supreme state advisory body to the Tsar in Imperial Russia. From 1906, it was the upper house of the parliament under the ...

in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, and then subject to debates in the Assemblies in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

and Iași; the Romanian translation followed the adoption of the Regulamentul in its French-language version. (Djuvara, p. 323).Giurescu, p. 123.It is probable that the title was chosen over designation as "Constitution(s)" in order to avoid the revolutionary meaning implied by the latter (Hitchins, p. 203). was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1831–1832 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

(the two Danubian Principalities that were to become the basis of the modern Romanian state). The document partially confirmed the traditional government (including rule by the ''hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or " master".

Etymology and Slavic usage

In the Slavonic language, ''hospodar'' is usually applied to the master/owner of a house or other properties and also the head of a family. ...

s'') and set up a common Russian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

which lasted until 1854. The Regulamentul itself remained in force until 1858. Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in its scope, it also engendered a period of unprecedented reforms which provided a setting for the Westernization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, econo ...

of the local society. The Regulamentul offered the two Principalities their first common system of government.

Background

The two principalities, owingtribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

and progressively ceding political control to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

since the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, had been subject to frequent Russian interventions as early as the Russo-Turkish War (1710–1711)

The Russo-Ottoman War of 1710—1711, also known as the Pruth River Campaign, was a brief military conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and the Ottoman Empire. The main battle took place during 18-22 July 1711 in the basin of the Pruth riv ...

, when a Russian army penetrated Moldavia and Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Peter the Great probably established links with the Wallachians. Eventually, the Ottomans enforced a tighter control on the region, effected under Phanariote ''hospodars'' (who were appointed directly by the Porte). Ottoman rule over the region remained contested by competition from Russia, which, as an Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

empire with claim to a Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

heritage, exercised notable influence over locals. At the same time, the Porte made several concessions to the rulers and boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia, as a means to ensure the preservation of its rule.

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayn ...

, signed in 1774 between the Ottomans and Russians, gave Russia the right to intervene on behalf of Eastern Orthodox Ottoman subjects in general, a right which it used to sanction Ottoman interventions in the Principalities in particular. Thus, Russia intervened to preserve reigns of ''hospodars'' who had lost Ottoman approval in the context of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(the '' casus belli'' for the 1806–12 conflict),Djuvara, pp. 282–4. and remained present in the Danubian states, vying for influence with the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

, well into the 19th century and annexing Moldavia's Bessarabia in 1812.

Despite the influx of Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, arriving in the Principalities as a new bureaucracy favored by the ''hospodars'', the traditional Estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed an ...

(the ''Divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

'') remained under the tight control of a number of high boyar families, who, while intermarrying with members of newly arrived communities, opposed reformist attempts—and successfully preserved their privileges by appealing against their competitors to both Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

and Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.

In the last decades of the 18th century, the growing strategic importance of the region brought about the establishment of

In the last decades of the 18th century, the growing strategic importance of the region brought about the establishment of consulates

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of diplomatic mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth coun ...

representing European powers directly interested in observing local developments (Russia, the Austrian Empire, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

; later, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

ones were opened as well).Iorga, ''Histoire des relations. La Monarchie de juillet…'' An additional way for consuls to exercise particular policies was the awarding of a privileged status and protection to various individuals, who were known as '' sudiți'' ("subjects", in the language of the time) of one or the other of the foreign powers.Giurescu, p. 288.

A seminal event occurred in 1821, when the rise of Greek nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

in various parts of the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

in connection with the Greek War of Independence led to occupation of the two states by the Filiki Eteria

Filiki Eteria or Society of Friends ( el, Φιλικὴ Ἑταιρεία ''or'' ) was a secret organization founded in 1814 in Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow the Ottoman rule of Greece and establish an independent Greek state. (''ret ...

, a Greek secret society who sought, and initially obtained, Russian approval. A mere takeover of the government in Moldavia, the Eterist expedition met a more complex situation in Wallachia, where a regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of high boyars attempted to have the anti-Ottoman Greek nationalists confirm both their rule and the rejection of Phanariote institutions. A compromise was achieved through their common support for Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu (; c. 1780 – ) was a Romanian revolutionary hero, the leader of the Wallachian uprising of 1821 and of the Pandur militia. He is also known as Tudor din Vladimiri (''Tudor from Vladimiri'') or, occasionally, as Domnul Tudo ...

, an Oltenia

Oltenia (, also called Lesser Wallachia in antiquated versions, with the alternative Latin names ''Wallachia Minor'', ''Wallachia Alutana'', ''Wallachia Caesarea'' between 1718 and 1739) is a historical province and geographical region of Romania ...

n ''pandur

The Pandurs were any of several light infantry military units beginning with Trenck's Pandurs, used by the Kingdom of Hungary from 1741, fighting in the War of the Austrian Succession and the Silesian Wars. Others to follow included Vladimirescu' ...

'' leader who had already instigated an anti-Phanariote rebellion (as one of the Russian ''sudiți'', it was hoped that Vladimirescu could assure Russia that the revolt was not aimed against its influence). However, the eventual withdrawal of Russian support made Vladimirescu seek a new agreement with the Ottomans, leaving him to be executed by an alliance of Eterists and weary locals (alarmed by his new anti-boyar program); after the Ottomans invaded the region and crushed the Eteria, the boyars, still perceived as a third party, obtained from the Porte an end to the Phanariote system.Giurescu, pp. 114–5.Hitchins, pp. 178–191.Iorga, ''Histoire des Roumains. Renaissance roumaine''.

Akkerman Convention and Treaty of Adrianople

The first reigns through locals— Ioniță Sandu Sturdza as Prince of Moldavia and

The first reigns through locals— Ioniță Sandu Sturdza as Prince of Moldavia and Grigore IV Ghica

Grigore IV Ghica or Grigore Dimitrie Ghica (June 30, 1755 – April 29, 1834) was Prince of Wallachia between 1822 and 1828. A member of the Ghica family, Grigore IV was the brother of Alexandru II Ghica and the uncle of Dora d'Istria.

While many ...

as Prince of Wallachia—were, in essence, short-lived: although the patron-client relation between Phanariote ''hospodars'' and a foreign ruler was never revived, Sturdza and Ghica were deposed by the Russian military intervention during the Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829. Sturdza's time on the throne was marked by an important internal development: the last in a series of constitutional proposals,Russo, VI–VII. advanced by boyars as a means to curb princely authority, ended in a clear conflict between the rapidly decaying class of low-ranking boyars (already forming the upper level of the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

rather than a segment of the traditional nobility) and the high-ranking families who had obtained the decisive say in politics. The proponent, Ionică Tăutu Ionică Tăutu (usual rendition of Ion Tăutu; 1798–1828) was a Moldavian low-ranking boyar, Enlightenment-inspired pamphleteer, and craftsman ("an engineer by trade", according to Alecu Russo).Russo, VI

Constitutional project

The last in a ...

, was defeated in the ''Divan'' after the Russian consul sided with the conservatives (expressing the official view that the aristocratic-republican and liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

aims of the document could have threatened international conventions in place).

On October 7, 1826, the Ottoman Empire—anxious to prevent Russia's intervention in the Greek Independence War—negotiatied with it a new status for the region in Akkerman

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi ( uk, Бі́лгород-Дністро́вський, Bílhorod-Dnistróvskyy, ; ro, Cetatea Albă), historically known as Akkerman ( tr, Akkerman) or under different names, is a city, municipality and port situated on ...

, one which conceded to several requests of the inhabitants: the resulting ''Akkerman Convention

The Akkerman Convention was a treaty signed on October 7, 1826, between the Russian and the Ottoman Empires in the Budjak citadel of ''Akkerman'' (present-day Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Ukraine). It imposed that the '' hospodars'' of Moldavia and Wal ...

'' was the first official document to nullify the principle of Phanariote reigns, instituting seven-year terms for new princes elected by the respective ''Divans'', and awarding the two countries the right to engage in unrestricted international trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significant ...

(as opposed to the tradition of limitations and Ottoman protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

, it only allowed Istanbul to impose its priorities in the grain trade).Djuvara, p. 320.Hitchins, pp. 198–9. The convention also made the first mention of new ''Statutes'', enforced by both powers as governing documents, which were not drafted until after the war—although both Sturdza and Ghica had appointed commissions charged with adopting such projects.Djuvara, p. 323.

The Russian military presence on the Principalities' soil was inaugurated in the first days of the war: by late April 1828, the Russian army of Peter Wittgenstein

, title = 1st Prince of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg-Berleburg

, image = Pjotr-christianowitsch-wittgenstein.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Portrait by George Dawe

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pereias ...

had reached the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

(in May, it entered present-day Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

). The campaign, prolonged for the following year and coinciding with devastating bubonic plague and cholera epidemics (which together killed around 1.6% of the population in both countries),Giurescu, p. 122. soon became a drain on local economy: according to British observers, the Wallachian state was required to indebt itself to European creditors for a total sum of ten million '' piastres'', in order to provide for the Russian army's needs. Accusations of widespread plunder were made by the French author Marc Girardin, who travelled in the region during the 1830s; Girardin alleged that Russian troops had confiscated virtually all cattle for their needs, and that Russian officers had insulted the political class by publicly stating that, in case the supply in oxen was to prove insufficient, boyars were to be tied to carts in their place—an accusation backed by Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica (; 12 August 1816 – 7 May 1897) was a Romanian statesman, mathematician, diplomat and politician, who was Prime Minister of Romania five times. He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president many times (1876–1882, ...

in his recollections.Ghica, ''Bârzof''.Girardin, in Djuvara, p. 321. He also recorded a mounting dissatisfaction with the new rule, mentioning that peasants were especially upset by the continuous maneuvers of troops inside the Principalities' borders.Girardin, in Djuvara, p. 323, writing down (1836) the words of a peasant who expressed his skepticism upon receiving news of Russian withdrawal in 1834: "…I see them leaving, returning, and turning their backs on each other, as if dancing. In order for them to leave, they would have to turn their backs on us, all of them, at once!" Overall, Russophilia

Russophilia (literally love of Russia or Russians) is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture. The antonym is Russophobia. In the 19th Century, ...

in the two Principalities appears to have suffered a major blow. Despite the confiscations, statistics of the time indicated that the pace of growth in heads of cattle remained steady (a 50% growth appears to have occurred between 1831 and 1837).

The Treaty of Adrianople, signed on September 14, 1829, confirmed both the Russian victory and the provisions of the Akkerman Convention, partly amended to reflect the Russian political ascendancy over the area. Furthermore, Wallachia's southern border was settled on the Danube thalweg

In geography and fluvial geomorphology, a thalweg or talweg () is the line of lowest elevation within a valley or watercourse.

Under international law, a thalweg is the middle of the primary navigable channel of a waterway that defines the boun ...

, and the state was given control over the previously Ottoman-ruled ports of Brăila, Giurgiu, and Turnu Măgurele

Turnu Măgurele () is a city in Teleorman County, Romania, in the historical region of Muntenia. Developed nearby the site once occupied by the medieval port of Turnu, it is situated north-east of the confluence between the Olt River and the Da ...

.Giurescu, pp. 122, 127. The freedom of commerce (which consisted mainly of grain exports from the region) and freedom of navigation on the river and on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

were passed into law, allowing for the creation of naval fleet

A fleet or naval fleet is a large formation of warships – the largest formation in any navy – controlled by one leader. A fleet at sea is the direct equivalent of an army on land.

Purpose

In the modern sense, fleets are usually, but not ne ...

s in both Principalities in the following years, as well as for a more direct contact with European traders, with the confirmation of the Moldavia and Wallachia's commercial privileges first stipulated at Akkerman (alongside the tight links soon established with Austrian and Sardinian traders, the first French ships visited Wallachia in 1830).

Russian occupation over Moldavia and Wallachia (as well as the Bulgarian town of Silistra) was prolonged pending the payment of war reparation

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

s by the Ottomans. Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Nicholas I assigned Fyodor Pahlen as governor over the two countries before the actual peace, as the first in a succession of three ''Plenipotentiary Presidents of the Divans in Moldavia and Wallachia'', and official supervisor of the two commissions charged with drafting the ''Statutes''. The bodies, having for secretaries Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi (, surname also spelled Asaki; 1 March 1788 – 12 November 1869) was a Moldavian, later Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist, engineer- border maker and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and ...

in Moldavia and Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei in Wallachia, had resumed their work while the cholera epidemic was still raging, and continued it after Pahlen had been replaced with Pyotr Zheltukhin in February 1829.

Adoption and character

The post-Adrianople state of affairs was perceived by many of the inhabitants of Wallachia and Moldavia as exceptionally abusive, given that Russia confiscated both of the Principalities' treasuries, and that Zheltukhin used his position to interfere in the proceedings of the commission, nominated his own choice of members, and silenced all opposition by having anti-Russian boyars expelled from the countries (including, notably, Iancu Văcărescu, a member of the Wallachian ''

The post-Adrianople state of affairs was perceived by many of the inhabitants of Wallachia and Moldavia as exceptionally abusive, given that Russia confiscated both of the Principalities' treasuries, and that Zheltukhin used his position to interfere in the proceedings of the commission, nominated his own choice of members, and silenced all opposition by having anti-Russian boyars expelled from the countries (including, notably, Iancu Văcărescu, a member of the Wallachian ''Divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

'' who had questioned his methods of government). According to the radical Ghica, "General Zheltukhin nd his subordinatesdefended all Russian abuse and injustice. Their system consisted in never listening to complaints, but rather rushing in with accusations, so as to inspire fear, so as the plaintiff would run away for fear of not having to endure a harsher thing than the cause of his riginalcomplaint". However, the same source also indicated that this behaviour was hiding a more complex situation: "Those who nevertheless knew Zheltukhin better… said that he was the fairest, most honest, and most kind of men, and that he gave his cruel orders with an aching heart. Many gave assurance that he had addressed to the emperor heart-breaking reports on the deplorable state in which the Principalities were to be found, in which he stated that Russia's actions in the Principalities deserved the scorn of the entire world".

The third and last Russian governor, Pavel Kiselyov

Count Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselyov or Kiseleff (Па́вел Дми́триевич Киселёв) (, Moscow – , Paris) is generally regarded as the most brilliant Russian reformer during Nicholas I's generally conservative reign.

Early m ...

(or ''Kiseleff''), took office on October 19, 1829, and faced his first major task in dealing with the last outbreaks of plague and cholera, as well as the threat of famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompani ...

,Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 51. with which he dealt by imposing quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

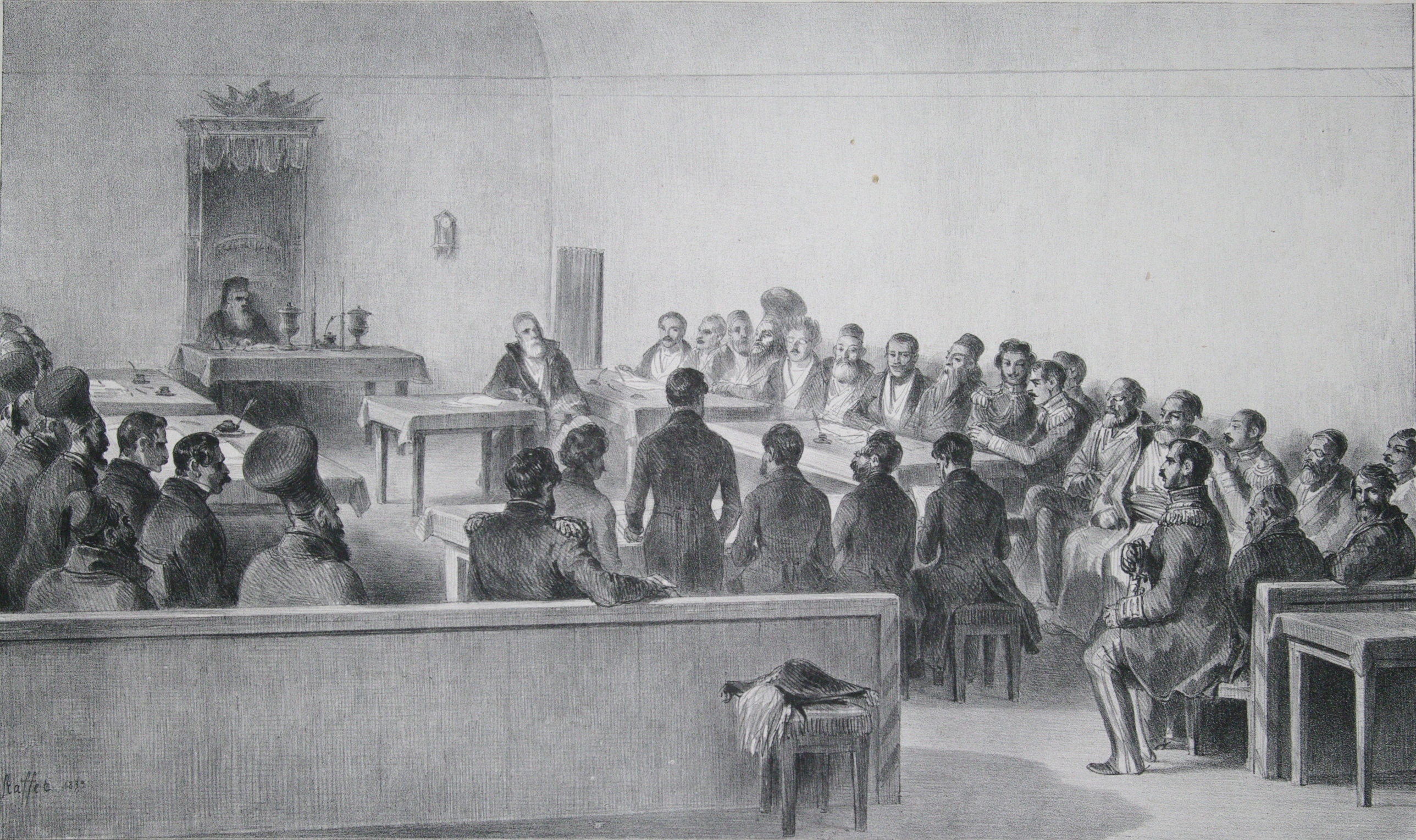

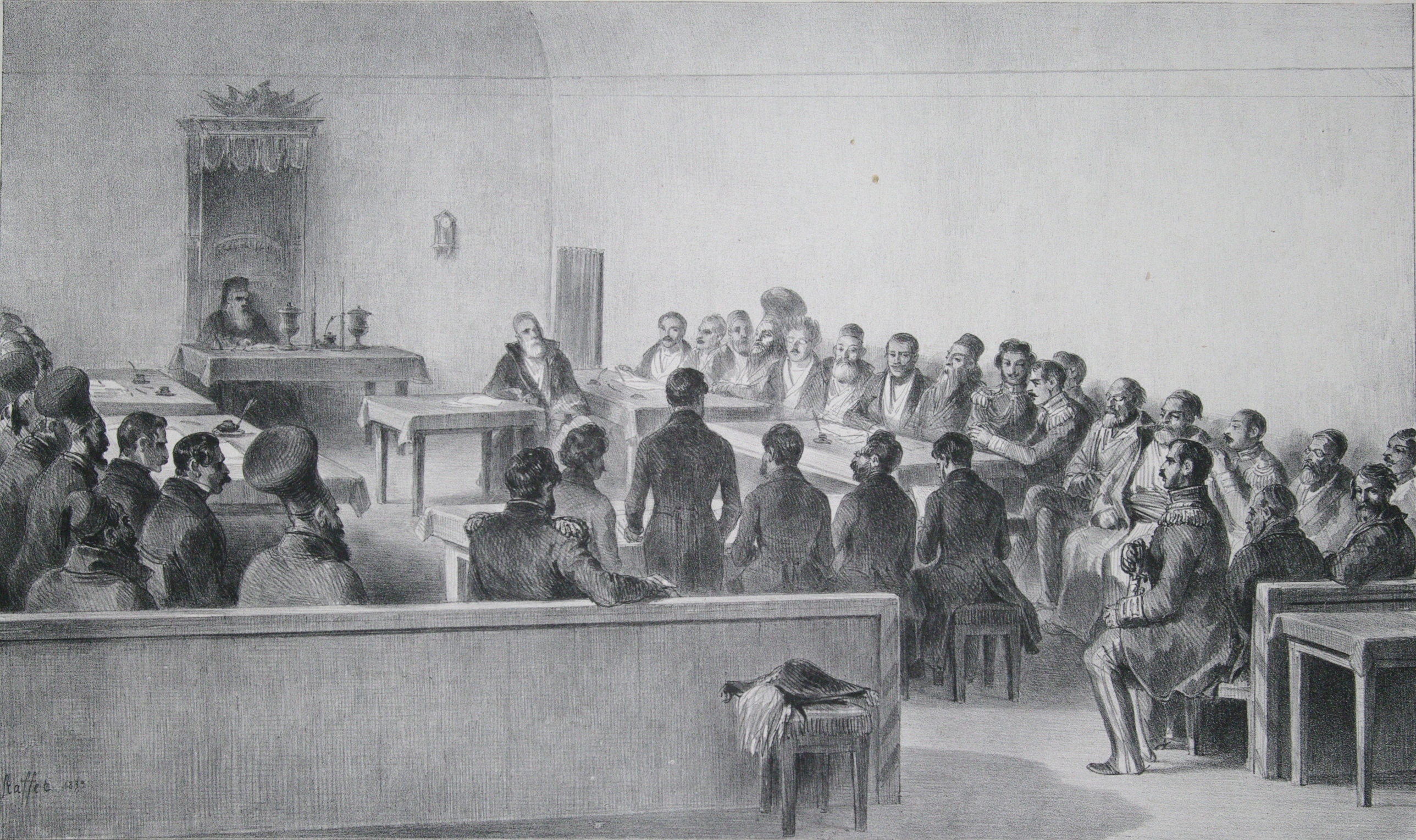

s and importing grain from Odessa.Hitchins, p. 202. His administration, lasting until April 1, 1834, was responsible for the most widespread and influential reforms of the period, and coincided with the actual enforcement of the new legislation. The earliest of Kiselyov's celebrated actions was the convening of the Wallachian ''Divan'' in November 1829, with the assurance that abuses were not to be condoned anymore.

''Regulamentul Organic'' was adopted in its two very similar versions on July 13, 1831 ( July 1, OS) in Wallachia and January 13, 1832 (January 1, OS) in Moldavia, after having minor changes applied to it in Saint Petersburg (where a second commission from the Principalities, presided by Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza (24 April 1794, Iași – 8 May 1884, Paris), sometimes anglicized as Michael Stourdza, was prince of Moldavia from 1834 to 1849. He was cousin of Roxandra Sturdza and Alexandru Sturdza.

Biography

He was son of Grigore Sturdza, s ...

and Alexandru Vilara, assessed it further). Its ratification by Ottoman Dynasty, Sultan Mahmud II was not a requirement from Kiselyov's perspective, who began enforcing it as a ''fait accompli'' before this was granted. The final version of the document sanctioned the first local government abiding by the principles of separation of powers, separation and balance of powers. The ''hospodars'', elected for life (and not for the seven-year term agreed in the ''Convention of Akkerman'') by an Extraordinary Assembly which comprised representation (politics), representatives of merchants and guilds, stood for the executive (government), executive, with the right to nominate ministers (whose offices were still referred to using the Historical Romanian ranks and titles, traditional titles of courtiers) and public officials; ''hospodars'' were to be voted in office by an electoral college with a confirmed majority of high-ranking boyars (in Wallachia, only 70 persons were members of the college).

Each National Assembly (approximate translation of ''Adunarea Obștească''), inaugurated in 1831–2, was a legislature itself under the control of high-ranking boyars, comprising 35 (in Moldavia) or 42 members (in Wallachia), voted into office by no more than 3,000 electors in each state; the judiciary was, for the very first time, removed from the control of ''hospodars''.Hitchins, pp. 204–5.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, pp. 51–2.Detailed membership of the Assembly in Wallachia: the Metropolitan of Hungro-Wallachia, Metropolitan bishop was president, and all other bishops were members, together with 20 high-ranking boyars and 18 other boyars (Hitchins, p. 204). In effect, the ''Regulament'' confirmed earlier steps leading to the eventual separation of church and state, and, although Romanian Orthodox Church, Orthodox church authorities were confirmed a privileged position and a political say, the religious institution was closely supervised by the government (with the establishment of a quasi-salary expense).Hitchins, p. 207.

A tax reform, fiscal reform ensued, with the creation of a Tax per head, poll tax (calculated per family), the elimination of most indirect taxes, annual state budgets (approved by the Assemblies) and the introduction of a civil list in place of the ''hospodars personal treasuries. New methods of bookkeeping were regulated, and the creation of national banks was projected, but, like the adoption of national fixed currency, fixed currencies, was never implemented.

According to the historian Nicolae Iorga, "The [boyar] oligarchy was appeased [by the ''Regulaments adoption]: a beautifully harmonious modern form had veiled the old Romania in the Middle Ages, medieval structure…. The ''bourgeoisie''… held no influence. As for the peasant, he lacked even the right to administer his own commune in Romania, commune, he was not even allowed to vote for an Assembly deemed, as if in jest, «national»." Nevertheless, conservative boyars remained suspicious of Russian tutelage, and several expressed their fear that the regime was a step leading to the creation of a regional ''guberniya'' for the Russian Empire. Their mistrust was, in time, reciprocated by Russia, who relied on ''hospodars'' and the direct intervention of its consuls to push further reforms.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 52. Kiselyov himself voiced a plan for the region's annexation to Russia, but the request was dismissed by his superiors.

Each National Assembly (approximate translation of ''Adunarea Obștească''), inaugurated in 1831–2, was a legislature itself under the control of high-ranking boyars, comprising 35 (in Moldavia) or 42 members (in Wallachia), voted into office by no more than 3,000 electors in each state; the judiciary was, for the very first time, removed from the control of ''hospodars''.Hitchins, pp. 204–5.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, pp. 51–2.Detailed membership of the Assembly in Wallachia: the Metropolitan of Hungro-Wallachia, Metropolitan bishop was president, and all other bishops were members, together with 20 high-ranking boyars and 18 other boyars (Hitchins, p. 204). In effect, the ''Regulament'' confirmed earlier steps leading to the eventual separation of church and state, and, although Romanian Orthodox Church, Orthodox church authorities were confirmed a privileged position and a political say, the religious institution was closely supervised by the government (with the establishment of a quasi-salary expense).Hitchins, p. 207.

A tax reform, fiscal reform ensued, with the creation of a Tax per head, poll tax (calculated per family), the elimination of most indirect taxes, annual state budgets (approved by the Assemblies) and the introduction of a civil list in place of the ''hospodars personal treasuries. New methods of bookkeeping were regulated, and the creation of national banks was projected, but, like the adoption of national fixed currency, fixed currencies, was never implemented.

According to the historian Nicolae Iorga, "The [boyar] oligarchy was appeased [by the ''Regulaments adoption]: a beautifully harmonious modern form had veiled the old Romania in the Middle Ages, medieval structure…. The ''bourgeoisie''… held no influence. As for the peasant, he lacked even the right to administer his own commune in Romania, commune, he was not even allowed to vote for an Assembly deemed, as if in jest, «national»." Nevertheless, conservative boyars remained suspicious of Russian tutelage, and several expressed their fear that the regime was a step leading to the creation of a regional ''guberniya'' for the Russian Empire. Their mistrust was, in time, reciprocated by Russia, who relied on ''hospodars'' and the direct intervention of its consuls to push further reforms.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 52. Kiselyov himself voiced a plan for the region's annexation to Russia, but the request was dismissed by his superiors.

Economic trends

Cities and towns

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

swelled in numbers, profiting from a growth in trade which had increased the status of merchants. Under continuous competition from the '' sudiți'', traditional guilds (''bresle'' or ''isnafuri'') faded away, leading to a more competitive, purely capitalism, capitalist environment.Giurescu, pp. 127, 288. This nevertheless signified that, although the traditional Greeks in Romania, Greek competition for Romanians, Romanian merchants and artisans had become less relevant, locals continued to face one from Austrian subjects of various nationalities, as well as from a sizeable History of the Jews in Romania, immigration of Jews from the Galicia (Central Europe), Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria and Russia—prevented from settling in the countryside, Jews usually became keepers of inns and taverns, and later both bankers and leasehold estate, leaseholders of estates.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 53. In this context, an anti-Roman Catholicism in Romania, Catholic sentiment was growing, based, according to Keith Hitchins, on the assumption that Catholicism and Austrian influence were closely related, as well as on a widespread preference for secularism.

The Romanian middle class formed the basis for what was to become the Liberalism in Romania, liberal electorate, and accounted for the xenophobia, xenophobic discourse of the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Party during the latter's first decade of existence (between 1875 and World War I).Pavlowitch, Chapter 9, pp. 185–7

Urban development occurred at a very fast pace: overall, the urban population had doubled by 1850. Population estimates for

The Romanian middle class formed the basis for what was to become the Liberalism in Romania, liberal electorate, and accounted for the xenophobia, xenophobic discourse of the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Party during the latter's first decade of existence (between 1875 and World War I).Pavlowitch, Chapter 9, pp. 185–7

Urban development occurred at a very fast pace: overall, the urban population had doubled by 1850. Population estimates for Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, the capital of Wallachia, were about 70,000 inhabitants in 1831, 60,000 in 1851,Chambers's EncyclopaediaVol. II, 1861 based on Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, 10th Edition and about 120,000 in 1859. For Iași, the capital of Moldavia, the estimates were 60,000 inhabitants for 1831, 70,000 for 1851, and about 65,000 for 1859. Brăila and Giurgiu, Danube ports returned to Wallachia by the Ottomans, as well as Moldavia's Galați, grew from the grain trade to become prosperous cities. Kiselyov, who had centered his administration on Bucharest, paid full attention to its development, improving its infrastructure and services and awarding it, together with all other cities and towns, a local administration (''see History of Bucharest''). Public works were carried out in the urban sphere, as well as in the massive expansion of the transport and communications system.Djuvara, p. 328.

Countryside

The success of the grain trade was secured by a conservative take on property, which restricted the right of peasants to exploit for their own gain those plots of land they leased on boyar estate (land), estates (the ''Regulament'' allowed them to consume around 70% of the total harvest per plot leased, while boyars were allowed to use a third of their estate as they pleased, without any legal duty toward the neighbouring peasant workforce); at the same time, small properties, created after Constantine Mavrocordatos had abolished serfdom in the 1740s, proved less lucrative in the face of competition by large estates—boyars profited from the consequences, as more landowning peasants had to resort to leasing plots while still owing ''corvées'' to their lords. Confirmed by the ''Regulament'' at up to 12 days a year, the ''corvée'' was still less significant than in other parts of Europe; however, since peasants relied on cattle for alternative food supplies and financial resources, and pastures remained the exclusive property of boyars, they had to exchange right of use for more days of work in the respective boyar's benefit (as much as to equate the corresponding ''corvée'' requirements in Central European countries, without ever being enforced by laws).Djuvara, p. 327. Several laws of the period display a particular concern in limiting the right of peasants to evade ''corvées'' by paying their equivalent in currency, thus granting the boyars a workforce to match a steady growth in grain demands on foreign markets.

In respect to pasture access, the ''Regulament'' divided peasants into three wealth-based categories: ''fruntași'' ("foremost people"), who, by definition, owned 4 working animals and one or more cows (allowed to use around 4 hectares of pasture); ''mijlocași'' ("middle people")—two working animals and one cow (around 2 hectares); ''codași'' ("backward people")—people who owned no property, and not allowed the use of pastures.

At the same time, the major demography, demographic changes took their toll on the countryside. For the very first time, food supplies were no longer abundant in front of a population growth ensured by, among other causes, the effective measures taken against epidemics; rural–urban migration became a noticeable phenomenon, as did the relative increase in urbanization of traditional rural areas, with an explosion of settlements around established fairs.

The success of the grain trade was secured by a conservative take on property, which restricted the right of peasants to exploit for their own gain those plots of land they leased on boyar estate (land), estates (the ''Regulament'' allowed them to consume around 70% of the total harvest per plot leased, while boyars were allowed to use a third of their estate as they pleased, without any legal duty toward the neighbouring peasant workforce); at the same time, small properties, created after Constantine Mavrocordatos had abolished serfdom in the 1740s, proved less lucrative in the face of competition by large estates—boyars profited from the consequences, as more landowning peasants had to resort to leasing plots while still owing ''corvées'' to their lords. Confirmed by the ''Regulament'' at up to 12 days a year, the ''corvée'' was still less significant than in other parts of Europe; however, since peasants relied on cattle for alternative food supplies and financial resources, and pastures remained the exclusive property of boyars, they had to exchange right of use for more days of work in the respective boyar's benefit (as much as to equate the corresponding ''corvée'' requirements in Central European countries, without ever being enforced by laws).Djuvara, p. 327. Several laws of the period display a particular concern in limiting the right of peasants to evade ''corvées'' by paying their equivalent in currency, thus granting the boyars a workforce to match a steady growth in grain demands on foreign markets.

In respect to pasture access, the ''Regulament'' divided peasants into three wealth-based categories: ''fruntași'' ("foremost people"), who, by definition, owned 4 working animals and one or more cows (allowed to use around 4 hectares of pasture); ''mijlocași'' ("middle people")—two working animals and one cow (around 2 hectares); ''codași'' ("backward people")—people who owned no property, and not allowed the use of pastures.

At the same time, the major demography, demographic changes took their toll on the countryside. For the very first time, food supplies were no longer abundant in front of a population growth ensured by, among other causes, the effective measures taken against epidemics; rural–urban migration became a noticeable phenomenon, as did the relative increase in urbanization of traditional rural areas, with an explosion of settlements around established fairs.

These processes also ensured that Industrial Revolution, industrialization was minimal (although factory, factories had first been opened during the Phanariotes): most revenues came from a highly productive agriculture based on peasant labour, and were invested back into agricultural production. In parallel, hostility between agricultural workers and landowners mounted: after an increase in lawsuits involving leaseholders and the decrease in quality of ''corvée'' outputs, resistance, hardened by the examples of

These processes also ensured that Industrial Revolution, industrialization was minimal (although factory, factories had first been opened during the Phanariotes): most revenues came from a highly productive agriculture based on peasant labour, and were invested back into agricultural production. In parallel, hostility between agricultural workers and landowners mounted: after an increase in lawsuits involving leaseholders and the decrease in quality of ''corvée'' outputs, resistance, hardened by the examples of Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu (; c. 1780 – ) was a Romanian revolutionary hero, the leader of the Wallachian uprising of 1821 and of the Pandur militia. He is also known as Tudor din Vladimiri (''Tudor from Vladimiri'') or, occasionally, as Domnul Tudo ...

and various ''hajduks'', turned to sabotage and occasional violence. A more serious incident occurred in 1831, when around 60,000 peasants protested against projected conscription criteria; Russian troops dispatched to quell the revolt killed around 300 people.

Political and cultural setting

The most noted cultural development under the ''Regulament'' was Romanian Romantic nationalism, in close connection with Francophile, Francophilia. Modernization, Institutional modernization engendered a renaissance of the intelligentsia. In turn, the concept of "nation" was first expanded beyond its coverage of the boyar category,Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 54. and more members of the privileged displayed a concern in solving problems facing the peasantry: although rarer among the high-ranking boyars, the interest was shared by most progressivism, progressive political figures by the 1840s.Djuvara, p. 331. Nationalist themes now included a preoccupation for the Origin of the Romanians, Latin origin of Romanians and the common (but since discarded) reference to the entire region as ''Dacia'' (first notable in the title of Mihail Kogălniceanu's ''Dacia Literară'', a short-lived Romantic literary magazine published in 1840). As a trans-border notion, ''Dacia'' also indicated a growth in Pan-Romanian sentiment—the latter had first been present in several boyar requests of the late 18th century, which had called for the union of the two Danubian Principalities under the protection of European powers (and, in some cases, under the rule of a foreign prince).Berindei, p. 8. To these was added the circulation of fake documents which were supposed to reflect the text of ''Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, Capitulations'' awarded by the

Nationalist themes now included a preoccupation for the Origin of the Romanians, Latin origin of Romanians and the common (but since discarded) reference to the entire region as ''Dacia'' (first notable in the title of Mihail Kogălniceanu's ''Dacia Literară'', a short-lived Romantic literary magazine published in 1840). As a trans-border notion, ''Dacia'' also indicated a growth in Pan-Romanian sentiment—the latter had first been present in several boyar requests of the late 18th century, which had called for the union of the two Danubian Principalities under the protection of European powers (and, in some cases, under the rule of a foreign prince).Berindei, p. 8. To these was added the circulation of fake documents which were supposed to reflect the text of ''Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, Capitulations'' awarded by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

to its Wallachian and Moldavian vassals in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, claiming to stand out as proof of rights and privileges which had been long neglected (''see also Islam in Romania'').Hitchins, pp. 192–3.

Education in Romania, Education, still accessible only to the wealthy, was first removed from the domination of the Greek language and Ancient Greece, Hellenism upon the disestablishment of Phanariotes sometime after 1821; the attempts of Gheorghe Lazăr (at the Saint Sava College) and Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi (, surname also spelled Asaki; 1 March 1788 – 12 November 1869) was a Moldavian, later Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist, engineer- border maker and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and ...

to engender a transition towards Romanian language, Romanian-language teaching had been only moderately successful, but Wallachia became the scene of such a movement after the start of Ion Heliade Rădulescu's teaching career and the first issue of his newspaper, ''Curierul Românesc''.Giurescu, p. 125.Hitchins, pp. 235–6. Moldavia soon followed, after Asachi began printing his highly influential magazine ''Albina Românească''.Hitchins, p. 244. The ''Regulament'' brought about the creation of new schools, which were dominated by the figures of Transylvanian Romanians who had taken exile after expressing their dissatisfaction with Austrian Empire, Austrian rule in their homeland—these teachers, who usually rejected the adoption of French cultural models in the otherwise conservatism, conservative society (viewing the process as an unnatural one), counted among them Ioan Maiorescu and August Treboniu Laurian. The Moldavian Regulation stipulated in article 421: "The course of all teachings will be in the Moldavian language, not only for the facilitation of the pupils and the cultivation of the language and the homeland, but also for the word that all public causes must be translated in this language, which the inhabitants use in church celebrations." Another impetus for nationalism was the Russian-supervised creation of small standing army, standing armies (occasionally referred to as "militias"; ''see Moldavian military forces and Wallachian military forces''). The Wallachian one first maneuvered in the autumn of 1831, and was supervised by Kiselyov himself. According to Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica (; 12 August 1816 – 7 May 1897) was a Romanian statesman, mathematician, diplomat and politician, who was Prime Minister of Romania five times. He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president many times (1876–1882, ...

, the prestige of military careers had a relevant tradition: "Only the arrival of the Muscovites [sic] in 1828 ended [the] young boyars' sons flighty way of life, as it made use of them as commissioners (''mehmendari'') in the service of Russian generals, in order to assist in providing the troops with [supplies]. In 1831 most of them took to the sword, signing up for the national militia."

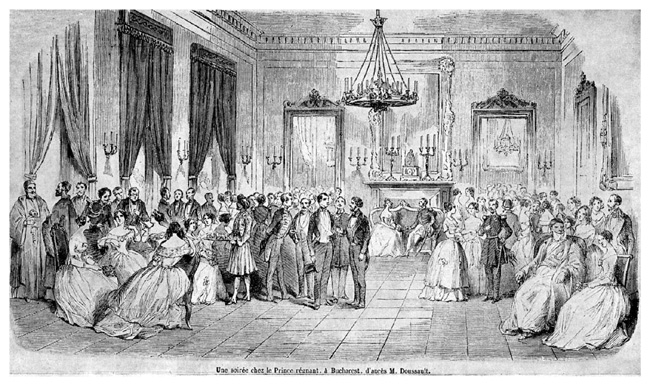

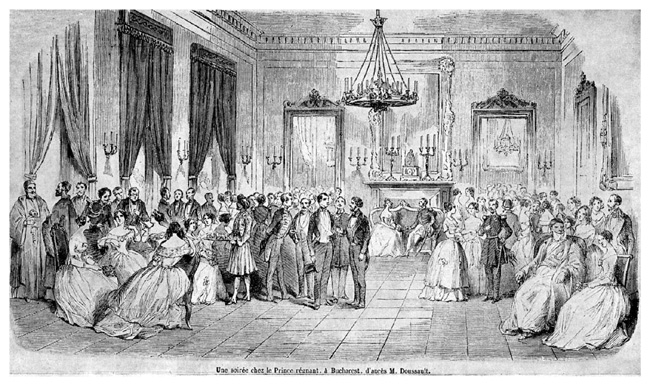

The

The Westernization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, econo ...

of Romanian society took place at a rapid pace, and created a noticeable, albeit not omnipresent, generation gap.Giurescu, pp. 125–6. The paramount cultural model was the French one, following a pattern already established by contacts between the region and the French Consulate and First French Empire, First Empire (attested, among others, by the existence of a Wallachian plan to petition Napoleon I of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, whom locals believed to be a descendant of the List of Byzantine Emperors, Byzantine Emperors, with a complaint against the Phanariotes,Ghica, ''Băltărețu''. as well as by an actual anonymous petition sent in 1807 from Moldavia). This trend was consolidated by the French cultural model partly adopted by the Russians, a growing mutual sympathy between the Principalities and France, increasingly obvious under the French July Monarchy, and, as early as the 1820s, the enrolment of young boyars in Parisian educational institutions (coupled with the 1830 opening of a French-language school in Bucharest, headed by Jean Alexandre Vaillant).Russo, IV.The refoundation of the Saint Sava College as a French-language school under Gheorghe Bibescu was, nevertheless, viewed with hostility by liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

political figures, who were by then stronger supporters of Romantic nationalism and, as such, of teaching in Romanian (Hitchins, p. 213) The young generation eventually attempted to curb French borrowings, which it had come to see as endangering its nationalist aspirations.

Statutory rules and nationalist opposition

In 1834, despite the founding documents' requirements, Russia and the Ottoman Empire agreed to appoint jointly the first two ''

In 1834, despite the founding documents' requirements, Russia and the Ottoman Empire agreed to appoint jointly the first two ''hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or " master".

Etymology and Slavic usage

In the Slavonic language, ''hospodar'' is usually applied to the master/owner of a house or other properties and also the head of a family. ...

s'' (instead of providing for their election), as a means to ensure both the monarchs' support for a moderate pace in reforms and their allegiance in front of conservative boyar opposition.Djuvara, p. 325. The choices were Alexandru II Ghica (the stepbrother of the previous monarch, Grigore IV Ghica, Grigore IV) as Prince of Wallachia and Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza (24 April 1794, Iași – 8 May 1884, Paris), sometimes anglicized as Michael Stourdza, was prince of Moldavia from 1834 to 1849. He was cousin of Roxandra Sturdza and Alexandru Sturdza.

Biography

He was son of Grigore Sturdza, s ...

(a distant cousin of Ioan Sturdza, Ioniță Sandu) as Prince of Moldavia. The two rulers (generally referred to as ''Domnii regulamentare''—"statutory" or "regulated reigns"), closely observed by the Russian consul (representative), consuls and various Russian technical advisors, soon met a vocal and unified opposition in the Assemblies and elsewhere.

Immediately after the confirmation of the ''Regulament'', Russia had begun demanding that the two local Assemblies each vote an ''Additional Article'' (''Articol adițional'')—one preventing any modification of the texts without the common approval of the courts in Istanbul and Saint Petersburg.Djuvara, p. 329.Hitchins, p. 210. In Wallachia, the issue turned into scandal after the pressure for adoption mounted in 1834, and led to a four-year-long standstill, during which a nationalist group in the legislative body began working on its own project for a constitution, proclaiming the Russian

Immediately after the confirmation of the ''Regulament'', Russia had begun demanding that the two local Assemblies each vote an ''Additional Article'' (''Articol adițional'')—one preventing any modification of the texts without the common approval of the courts in Istanbul and Saint Petersburg.Djuvara, p. 329.Hitchins, p. 210. In Wallachia, the issue turned into scandal after the pressure for adoption mounted in 1834, and led to a four-year-long standstill, during which a nationalist group in the legislative body began working on its own project for a constitution, proclaiming the Russian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

and Ottoman suzerainty to be over, and self-determination with guarantees from all European Powers of the time.Hitchins, pp. 210–1. The radical leader of the movement, Ion Câmpineanu, maintained close contacts with Poles, Polish nobleman Adam Jerzy Czartoryski's Union of National Unity (as well as with other European nationalists Romantics); after the ''Additional Article'' passed due to Ghica's interference and despite boyar protests, Câmpineanu was forced to abandon his seat and take refuge in Central Europe (until being arrested and sent back by the Austrians to be imprisoned in Bucharest). From that point on, opposition to Ghica's rule took the form of Freemasonry, Freemason and ''carbonari''-inspired conspiracy (political), conspiracies, formed around young politicians such as Mitică Filipescu, Nicolae Bălcescu, Eftimie Murgu, Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica (; 12 August 1816 – 7 May 1897) was a Romanian statesman, mathematician, diplomat and politician, who was Prime Minister of Romania five times. He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president many times (1876–1882, ...

, Christian Tell, Dimitrie Macedonski, and Cezar Bolliac (all of whom held Câmpineanu's ideology in esteem)—in 1840, Filipescu and most of his group (who had tried in vain to profit from the Ottoman crisis engendered by Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali's rebellion) were placed under arrest and imprisoned in various locations.Giurescu, pp. 132–3.

Noted abuses against the rule of law and the consequent threat of rebellion made the Ottoman Empire and Russia withdraw their support for Ghica in 1842,Hitchins, p. 212. and his successor, Gheorghe Bibescu, reigned as the first and only prince to have been elected by any one of the two Assemblies. In Moldavia, the situation was less tense, as Sturdza was able to calm down and manipulate opposition to Russian rule while introducing further reforms.Hitchins, pp. 213–5.

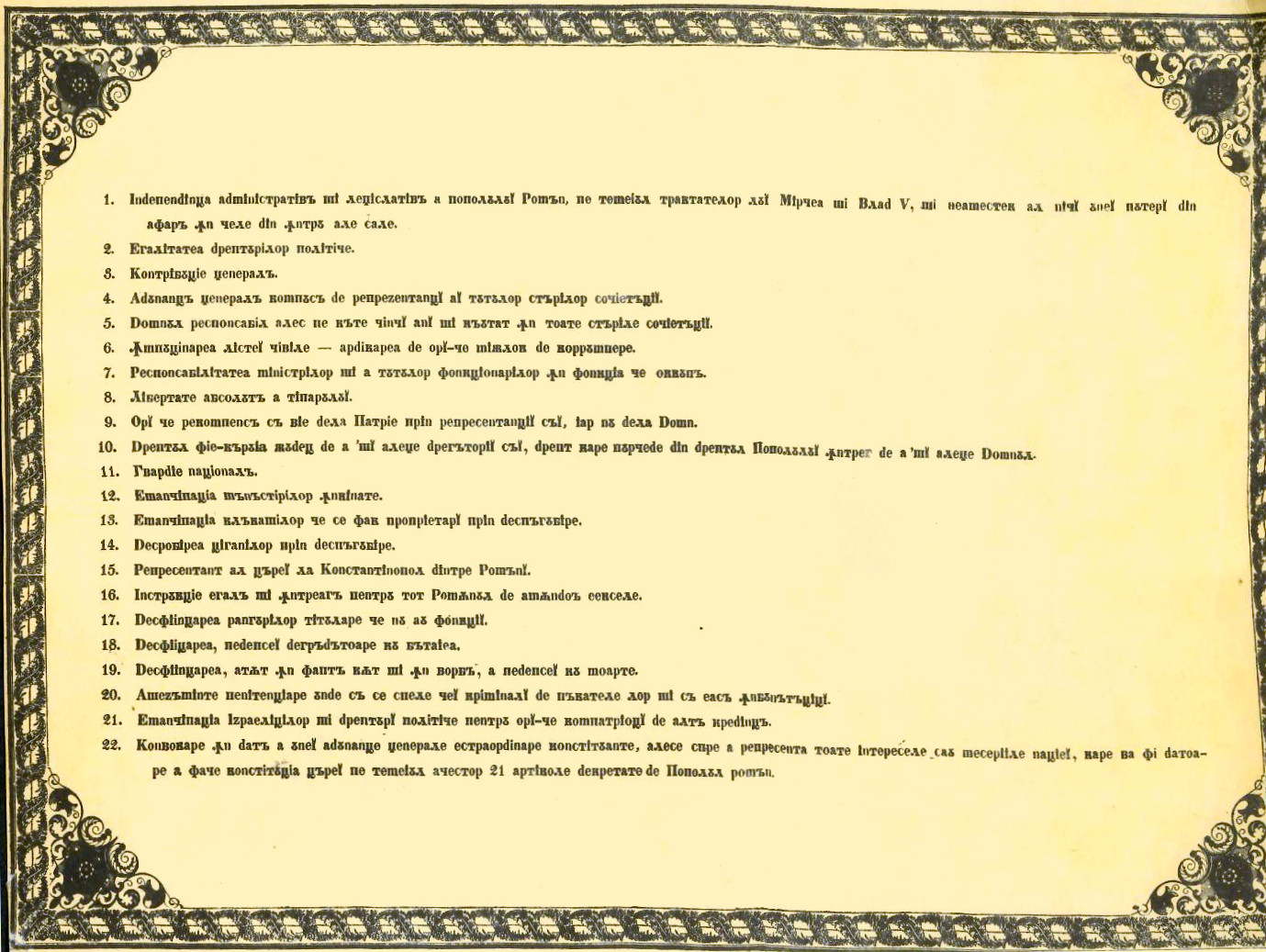

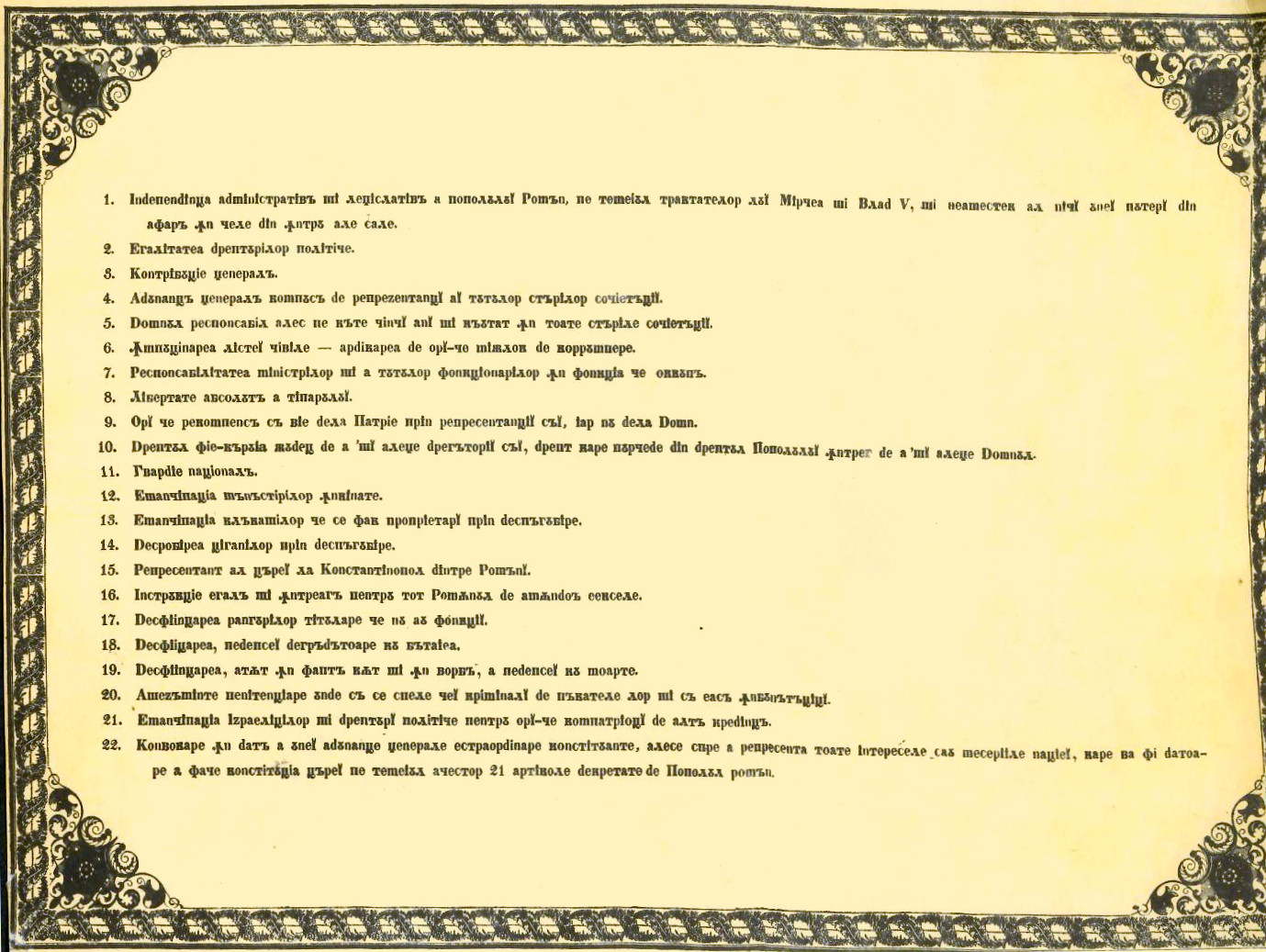

In 1848, upon the outbreak of the Revolutions of 1848, European revolutions, Liberalism in Romania, liberalism consolidated itself into more overt opposition, helped along by contacts between Romanian students with the Revolutions of 1848 in France, French movement. Nevertheless, the 1848 Moldavian revolution, Moldavian revolution of late March 1848 was an abortive one, and led to the return of Russian troops on its soil.Hitchins, pp. 292–4. 1848 Wallachian revolution, Wallachia's revolt was successful: after the ''Proclamation of Islaz'' on June 21 sketched a new legal framework and land reform with an end to all ''corvées'' (a program acclaimed by the crowds), the conspirators managed to topple Bibescu, who had by then dissolved the Assembly, without notable violence, and established a Provisoral Government in Bucharest.Giurescu, pp. 133–5.Hitchins, pp. 294–307.Pavlowitch, Chapter 3, p. 55.