Reform Jews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major

"As Reform Jews Gather, Some Good News in the Numbers"

''

"Members and Motives: Who Joins American Jewish Congregations and Why"

, S3K Report, Fall 2006 Based on these, the URJ claims to represent 2.2 million people. It has 845 congregations in the U.S. and 27 in Canada, the vast majority of the 1,170 affiliated with the WUPJ that are not Reconstructionist. Its rabbinical arm is the

With the advent of

With the advent of  An isolated, yet much more radical step in the same direction as Hamburg's, was taken across the ocean in 1824. The younger congregants in the Charleston synagogue " Beth Elohim" were disgruntled by present conditions and demanded change. Led by

An isolated, yet much more radical step in the same direction as Hamburg's, was taken across the ocean in 1824. The younger congregants in the Charleston synagogue " Beth Elohim" were disgruntled by present conditions and demanded change. Led by

In the 1820s and 1830s, philosophers like

In the 1820s and 1830s, philosophers like

At Charleston, the former members of the Reformed Society gained influence over the affairs of ''Beth Elohim''. In 1836, Gustavus Poznanski was appointed minister. At first traditional, but around 1841, he excised the Resurrection of the Dead and abolished the

At Charleston, the former members of the Reformed Society gained influence over the affairs of ''Beth Elohim''. In 1836, Gustavus Poznanski was appointed minister. At first traditional, but around 1841, he excised the Resurrection of the Dead and abolished the

In Germany, Liberal communities stagnated since mid-century. Full and complete

In Germany, Liberal communities stagnated since mid-century. Full and complete

Kohler retired in 1923. Rabbi Samuel S. Cohon was appointed HUC Chair of Theology in his stead, serving until 1956. Cohon, born near

Kohler retired in 1923. Rabbi Samuel S. Cohon was appointed HUC Chair of Theology in his stead, serving until 1956. Cohon, born near

"Classical Reform revival pushes back against embrace of tradition"

Reform Judaism

Union for Reform Judaism

World Union for Progressive Judaism

Central Conference of American Rabbis

American Conference of Cantors

Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion

''Reform Judaism'' magazine

Liberal Judaism in the UK

The Movement for Reform Judaism in the UK

Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism

Unión del Judaísmo Reformista - Amlat

Instituto de Formación Rabínica Reformista

{{Authority control

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination

Jewish religious movements, sometimes called " denominations", include different groups within Judaism which have developed among Jews from ancient times. Today, the most prominent divisions are between traditionalist Orthodox movements (includi ...

that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous search for truth and knowledge, which is closely intertwined with human reason and not limited to the theophany at Mount Sinai. A highly liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and ...

strand of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

, it is characterized by lessened stress on ritual and personal observance, regarding ''halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' (Jewish law) as non-binding and the individual Jew as autonomous, and great openness to external influences and progressive values.

The origins of Reform Judaism lie in 19th-century Germany, where Rabbi Abraham Geiger

Abraham Geiger (Hebrew: ''ʼAvrāhām Gayger''; 24 May 181023 October 1874) was a German rabbi and scholar, considered the founding father of Reform Judaism. Emphasizing Judaism's constant development along history and universalist traits, Geige ...

and his associates formulated its early principles. Since the 1970s, the movement has adopted a policy of inclusiveness and acceptance, inviting as many as possible to partake in its communities rather than adhering to strict theoretical clarity. It is strongly identified with progressive and liberal agendas in political and social terms, mainly under the traditional Jewish rubric ''tikkun olam

''Tikkun olam'' ( he, תִּיקּוּן עוֹלָם, , repair of the world) is a concept in Judaism, which refers to various forms of action intended to repair and improve the world.

In classical rabbinic literature, the phrase referred to le ...

'' ("repairing of the world"). ''Tikkun olam'' is a central motto of Reform Judaism, and taking positive action for its own sake is one of the main channels for adherents to express their affiliation. The movement's most significant center today is in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the C ...

.

Various regional branches exist, including the Union for Reform Judaism

The Union for Reform Judaism (URJ), known as the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC) until 2003, founded in 1873 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the congregational arm of Reform Judaism in North America. The other two arms established b ...

(URJ) in the United States, the Movement for Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism (formally the Movement for Reform Judaism and known as Reform Synagogues of Great Britain until 2005) is one of the two World Union for Progressive Judaism–affiliated denominations in the United Kingdom. Reform is relatively ...

(MRJ) and Liberal Judaism in the United Kingdom, the Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism

The Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism (IMPJ; he, התנועה הרפורמית – יהדות מתקדמת בישראל) is the organizational branch of Progressive Judaism in Israel, and a member organization of the World Union ...

(IMPJ) in Israel and the UJR-AmLat in Latin America; these are united under the banner of the international World Union for Progressive Judaism

The World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ) is the international umbrella organization for the various branches of Reform, Liberal and Progressive Judaism, as well as the separate Reconstructionist Judaism. The WUPJ is based in 40 countries ...

(WUPJ). Founded in 1926, the WUPJ estimates it represents at least 1.8 million people in 50 countries, just under 1 million of which are registered adult congregants, as well as many unaffiliated individuals who identify with the denomination. This makes it the second-largest Jewish denomination worldwide, after Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on ...

.

Definitions

Its inherent pluralism and the importance which it places on individual autonomy impedes any simplistic definition of Reform Judaism; its various strands regard Judaism throughout the ages as a religion which was derived from a process of constant evolution. They warrant and obligate further modifications and reject any fixed, permanent set of beliefs, laws or practices. A clear description of Reform Judaism became particularly challenging since the turn toward a policy which favored inclusiveness ("Big Tent" in the United States) over a coherent theology in the 1970s. This transition largely overlapped with what researchers termed the transition from "Classical" to "New" Reform Judaism in America, paralleled in the other, smaller branches of Judaism which exist across the world. The movement ceased stressing principles and core beliefs, focusing more on the personal spiritual experience and communal participation. This shift was not accompanied by a distinct new doctrine or by the abandonment of the former, but rather with ambiguity. The leadership allowed and encouraged a wide variety of positions, from selective adoption of ''halakhic

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' observance to elements approaching religious humanism.

The declining importance of the theoretical foundation, in favour of pluralism and equivocalness, drew large crowds of newcomers. It also diversified Reform to a degree that made it hard to formulate a clear definition of it. Early and "Classical" Reform were characterized by a move away from traditional forms of Judaism combined with a coherent theology; "New Reform" sought, to a certain level, the reincorporation of many formerly discarded elements within the framework established during the "Classical" stage, though this very doctrinal basis became increasingly obfuscated.

Critics, like Rabbi Dana Evan Kaplan

Dana Evan Kaplan (born October 29, 1960) is a Reform rabbi known for his writings on Reform Judaism and American Judaism. He has also written on other subjects, including American Jewish history and Jews in various diaspora communities. Kaplan ha ...

, warned that Reform became more of a ''Jewish activities club'', a means to demonstrate some affinity to one's heritage in which even rabbinical students do not have to believe in any specific theology or engage in any particular practice, rather than a defined belief system.

Theology

God

In regard to God, while some voices among the spiritual leadership approachedreligious

Religion is usually defined as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, tran ...

and even secular humanism

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality ...

– a tendency that grew increasingly from the mid-20th century, both among clergy and constituents, leading to broader, dimmer definitions of the concept – the movement had always officially maintained a theistic

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

stance, affirming the belief in a personal God

A personal god, or personal goddess, is a deity who can be related to as a person, instead of as an impersonal force, such as the Absolute, "the All", or the "Ground of Being".

In the scriptures of the Abrahamic religions, God is described as b ...

.

Early Reform thinkers in Germany clung to this precept; the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform The Pittsburgh Platform is a pivotal 1885 document in the history of the American Reform Movement in Judaism that called for Jews to adopt a modern approach to the practice of their faith. While it was never formally adopted by the Union of Americ ...

described the "One God... The God-Idea as taught in our sacred Scripture" as consecrating the Jewish people to be its priests. It was grounded on a wholly theistic understanding, although the term "God-idea" was excoriated by outside critics. So was the 1937 Columbus Declaration of Principles, which spoke of "One, living God who rules the world". Even the 1976 San Francisco Centenary Perspective, drafted at a time of great discord among Reform theologians, upheld "the affirmation of God... Challenges of modern culture have made a steady belief difficult for some. Nevertheless, we ground our lives, personally and communally, on God's reality." The 1999 Pittsburgh Statement of Principles declared the "reality and oneness of God". British Liberal Judaism affirms the "Jewish conception of God: One and indivisible, transcendent and immanent, Creator and Sustainer".

Revelation

The basic tenet of Reform theology is a belief in a continuous, or progressive,revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on ...

,Eugene B. Borowitz, ''Reform Judaism Today'', Behrman House, 1993. pp. 147–148. occurring continuously and not limited to the theophany at Sinai, the defining event in traditional interpretation. According to this view, all holy scripture of Judaism, including the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

, were authored by human beings who, although under divine inspiration

Divine inspiration is the concept of a supernatural force, typically a deity, causing a person or people to experience a creative desire. It has been a commonly reported aspect of many religions, for thousands of years. Divine inspiration is often ...

, inserted their understanding and reflected the spirit of their consecutive ages. All the People of Israel

Israelis ( he, יִשְׂרָאֵלִים, translit=Yīśrāʾēlīm; ar, الإسرائيليين, translit=al-ʾIsrāʾīliyyin) are the citizens and nationals of the State of Israel. The country's populace is composed primarily of Jew ...

are a further link in the chain of revelation, capable of reaching new insights: religion can be renewed without necessarily being dependent on past conventions. The chief promulgator of this concept was Abraham Geiger

Abraham Geiger (Hebrew: ''ʼAvrāhām Gayger''; 24 May 181023 October 1874) was a German rabbi and scholar, considered the founding father of Reform Judaism. Emphasizing Judaism's constant development along history and universalist traits, Geige ...

, generally considered the founder of the movement. After critical research led him to regard scripture as a human creation, bearing the marks of historical circumstances, he abandoned the belief in the unbroken perpetuity of tradition derived from Sinai and gradually replaced it with the idea of progressive revelation.

As in other liberal denominations, this notion offered a conceptual framework for reconciling the acceptance of critical research with the maintenance of a belief in some form of divine communication, thus preventing a rupture among those who could no longer accept a literal understanding of revelation. No less importantly, it provided the clergy with a rationale for adapting, changing and excising traditional mores and bypassing the accepted conventions of Jewish Law, rooted in the orthodox concept of the explicit transmission of both scripture and its oral interpretation. While also subject to change and new understanding, the basic premise of progressive revelation endures in Reform thought.

In its early days, this notion was greatly influenced by the philosophy of German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionar ...

, from which its founders drew much inspiration: belief in humanity marching toward a full understanding of itself and the divine, manifested in moral progress towards perfection. This highly rationalistic view virtually identified human reason and intellect with divine action, leaving little room for direct influence by God. Geiger conceived revelation as occurring via the inherent "genius" of the People Israel, and his close ally Solomon Formstecher described it as the awakening of oneself into full consciousness of one's religious understanding. The American theologian Kaufmann Kohler

Kaufmann Kohler (May 10, 1843 – January 28, 1926) was a German-born Jewish American biblical scholar and critic, theologian, Reform rabbi, and contributing editor to numerous articles of ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'' (1906).

Life and work

Kauf ...

also spoke of the "special insight" of Israel, almost fully independent from direct divine participation, and English thinker Claude Montefiore

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, also Goldsmid–Montefiore or just Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) was the intellectual founder of Anglo- Liberal Judaism and the founding president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a schola ...

, founder of Liberal Judaism, reduced revelation to "inspiration", according intrinsic value only to the worth of its content, while "it is not the place where they are found that makes them inspired". Common to all these notions was the assertion that present generations have a higher and better understanding of divine will, and they can and should unwaveringly change and refashion religious precepts.Jakob Josef Petuchowski, "The Concept of Revelation in Reform Judaism", in ''Studies in Modern Theology and Prayer'', Jewish Publication Society, 1998. pp. 101–112.

In the decades around World War II, this rationalistic and optimistic theology was challenged and questioned. It was gradually replaced, mainly by the Jewish existentialism of Martin Buber

Martin Buber ( he, מרטין בובר; german: Martin Buber; yi, מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 –

June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism ...

and Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig (, ; 25 December 1886 – 10 December 1929) was a German theologian, philosopher, and translator.

Early life and education

Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany, to an affluent, minimally observant Jewish family. His fa ...

, centered on a complex, personal relationship with the creator, and a more sober and disillusioned outlook. The identification of human reason with Godly inspiration was rejected in favour of views such as Rosenzweig's, who emphasized that the only content of revelation is it in itself, while all derivations of it are subjective, limited human understanding. However, while granting higher status to historical and traditional understanding, both insisted that "revelation is certainly not Law giving" and that it did not contain any "finished statements about God", but, rather, that human subjectivity shaped the unfathomable content of the Encounter and interpreted it under its own limitations. The senior representative of postwar Reform theology, Eugene Borowitz, regarded theophany in postmodern terms and closely linked it with quotidian human experience and interpersonal contact. He rejected the notion of "progressive revelation" in the meaning of comparing human betterment with divine inspiration, stressing that past experiences were "unique" and of everlasting importance. Yet he stated that his ideas by no means negated the concept of ongoing, individually experienced revelation by all.

Ritual, autonomy and law

Reform Judaism emphasizes the ethical facets of the faith as its central attribute, superseding the ceremonial ones. Reform thinkers often cited theProphets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

' condemnations of ceremonial acts, lacking true intention and performed by the morally corrupt, as testimony that rites have no inherent quality. Geiger centered his philosophy on the Prophets' teachings (He named his ideology "Prophetic Judaism" already in 1838), regarding morality and ethics as the stable core of a religion in which ritual observance transformed radically through the ages. However, practices were seen as a means to elation and a link to the heritage of the past, and Reform generally argued that rituals should be maintained, discarded or modified based on whether they served these higher purposes. This stance allowed a great variety of practice both in the past and the present. In "Classical" times, personal observance was reduced to little beyond nothing. The postwar "New Reform" lent renewed importance to practical, regular action as a means to engage congregants, abandoning the sanitized forms of the "Classical".

Another key aspect of Reform doctrine is the personal autonomy of each adherent, who may formulate their own understanding and expression of their religiosity. Reform is unique among all Jewish denominations in placing the individual as the authorized interpreter of Judaism. This position was originally influenced by Kantian

Kantianism is the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). The term ''Kantianism'' or ''Kantian'' is sometimes also used to describe contemporary positions in philosophy of mind ...

philosophy and the great weight it lent to personal judgement and free will. This highly individualistic stance also proved one of the movement's great challenges, for it impeded the creation of clear guidelines and standards for positive participation in religious life and definition of what was expected from members.

The notion of autonomy coincided with the gradual abandonment of traditional practice (largely neglected by most members, and the Jewish public in general, before and during the rise of Reform) in the early stages of the movement. It was a major characteristic during the "Classical" period, when Reform closely resembled Protestant surroundings. Later, it was applied to encourage adherents to seek their own means of engaging Judaism. "New Reform" embraced the criticism levied by Rosenzweig and other thinkers at extreme individualism, laying a greater stress on community and tradition. Though by no means declaring that members were bound by a compelling authority of some sort – the notion of an intervening, commanding God remained foreign to denominational thought. The "New Reform" approach to the question is characterized by an attempt to strike a mean between autonomy and some degree of conformity, focusing on a dialectic relationship between both.

The movement never entirely abandoned ''halachic'' (traditional jurisprudence) argumentation, both due to the need for precedent to counter external accusations and the continuity of heritage. Instead, the movement had largely made ethical considerations or the spirit of the age the decisive factor in determining its course. The German founding fathers undermined the principles behind the legalistic process, which was based on a belief in an unbroken tradition through the ages merely elaborated and applied to novel circumstances, rather than subject to change. Rabbi Samuel Holdheim

Samuel Holdheim (1806 – 22 August 1860) was a German rabbi and author, and one of the more extreme leaders of the early Reform Movement in Judaism. A pioneer in modern Jewish homiletics, he was often at odds with the Orthodox community.(Hist ...

advocated a particularly radical stance, arguing that the ''halachic'' Law of the Land is Law principle must be universally applied and subject virtually everything to current norms and needs, far beyond its weight in conventional Jewish Law.

While Reform rabbis in 19th-century Germany had to accommodate conservative elements in their communities, at the height of "Classical Reform" in the United States, ''halakhic'' considerations could be virtually ignored and Holdheim's approach embraced. In the 1930s and onwards, Rabbi Solomon Freehof

Solomon Bennett Freehof (August 8, 1892 – 1990) was a prominent Reform rabbi, posek, and scholar. Rabbi Freehof served as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis and the World Union for Progressive Judaism. Beginning in 1955, h ...

and his supporters reintroduced such elements, but they too regarded Jewish Law as too rigid a system. Instead, they recommended that selected features will be readopted and new observances established in a piecemeal fashion, as spontaneous ''minhag

''Minhag'' ( he, מנהג "custom", classical pl. מנהגות, modern pl. , ''minhagim'') is an accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism. A related concept, ''Nusach'' (), refers to the traditional order and form of the prayers.

Etym ...

'' (custom) emerging by trial and error and becoming widespread if it appealed to the masses. The advocates of this approach also stress that their responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

are of non-binding nature, and their recipients may adapt them as they see fit. Freehof's successors, such as Rabbis Walter Jacob

Walter Jacob (born 1930) is an American Reform rabbi who was born in Augsburg, Germany, and immigrated to the United States in 1940.

He received his B.A. from Drury College (Springfield, Missouri, 1950) and ordination and an M.H.L. from Hebrew Uni ...

and Moshe Zemer, further elaborated the notion of "Progressive ''Halakha''" along the same lines.

Messianic age and election

Reform sought to accentuate and greatly augment the universalist traits in Judaism, turning it into a faith befitting the Enlightenment ideals ubiquitous at the time it emerged. The tension between universalism and the imperative to maintain uniqueness characterized the movement throughout its entire history. Its earliest proponents rejectedDeism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of ...

and the belief that all religions would unite into one, and it later faced the challenges of the Ethical movement

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an ethical, educational, and religion, religious movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (professor), Felix Adler ...

and Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there ...

. Parallel to that, it sought to diminish all components of Judaism that it regarded as overly particularist and self-centered: petitions expressing hostility towards gentiles were toned down or excised, and practices were often streamlined to resemble surrounding society. "New Reform" laid a renewed stress on Jewish particular identity, regarding it as better suiting popular sentiment and need for preservation.

One major expression of that, which is the first clear Reform doctrine to have been formulated, is the idea of universal Messianism

Messianism is the belief in the advent of a messiah who acts as the savior of a group of people. Messianism originated as a Zoroastrianism religious belief and followed to Abrahamic religions, but other religions have messianism-related concepts ...

. The belief in redemption was unhinged from the traditional elements of return to Zion

The return to Zion ( he, שִׁיבָת צִיּוֹן or שבי ציון, , ) is an event recorded in Ezra–Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah—subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire—were freed from th ...

and restoration of the Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temple ...

and the sacrificial cult therein, and turned into a general hope for salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

. This was later refined when the notion of a personal Messiah who would reign over Israel was officially abolished and replaced by the concept of a Messianic Age

In Abrahamic religions, the Messianic Age is the future period of time on Earth in which the messiah will reign and bring universal peace and brotherhood, without any evil. Many believe that there will be such an age; some refer to it as the cons ...

of universal harmony and perfection. The considerable loss of faith in human progress around World War II greatly shook this ideal, but it endures as a precept of Reform.

Another key example is the reinterpretation of the election of Israel. The movement maintained the idea of the Chosen People of God, but recast it in a more universal fashion: it isolated and accentuated the notion (already present in traditional sources) that the mission of Israel was to spread among all nations and teach them divinely-inspired ethical monotheism, bringing them all closer to the Creator. One extreme "Classical" promulgator of this approach, Rabbi David Einhorn, substituted the lamentation on the Ninth of Av

Tisha B'Av ( he, תִּשְׁעָה בְּאָב ''Tīšʿā Bəʾāv''; , ) is an annual fast day in Judaism, on which a number of disasters in Jewish history occurred, primarily the destruction of both Solomon's Temple by the Neo-Babylonian E ...

for a celebration, regarding the destruction of Jerusalem as fulfilling God's scheme to bring his word, via his people, to all corners of the earth. Highly self-centered affirmations of Jewish exceptionalism were moderated, although the general notion of "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation" retained. On the other hand, while embracing a less strict interpretation compared to the traditional one, Reform also held to this tenet against those who sought to deny it. When secularist thinkers like Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

and Mordecai Kaplan

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (born Mottel Kaplan; June 11, 1881 – November 8, 1983), was a Lithuanian-born American rabbi, writer, Jewish educator, professor, theologian, philosopher, activist, and religious leader who founded the Reconstructioni ...

forwarded the view of Judaism as a civilization

''Judaism as a Civilization: Toward a Reconstruction of American-Jewish Life'' is a 1934 work on Judaism and American Jewish life by Rabbi Mordecai M. Kaplan, the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism is a Jewish move ...

, portraying it as a culture created by the Jewish people, rather than a God-given faith defining them, Reform theologians decidedly rejected their position – although it became popular and even dominant among rank-and-file members. Like the Orthodox, they insisted that the People Israel was created by divine election alone, and existed solely as such. The 1999 Pittsburgh Platform and other official statements affirmed that the "Jewish people is bound to God by an eternal ''B'rit'', covenant".

Soul and afterlife

As part of its philosophy, Reform anchored reason in divine influence, accepted scientific criticism of hallowed texts and sought to adapt Judaism to modern notions of rationalism. In addition to the other traditional precepts its founders rejected, they also denied the belief in the future bodilyresurrection of the dead

General resurrection or universal resurrection is the belief in a resurrection of the dead, or resurrection from the dead (Koine: , ''anastasis onnekron''; literally: "standing up again of the dead") by which most or all people who have died w ...

. It was viewed both as irrational and an import from ancient middle-eastern pagans. Notions of afterlife were reduced merely to the immortality of the soul

Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is “sleeping” after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the inter ...

. While the founding thinkers, like Montefiore, all shared this belief, the existence of a soul became harder to cling to with the passing of time. In the 1980s, Borowitz could state that the movement had nothing coherent to declare in the matter. The various streams of Reform still largely, though not always or strictly, uphold the idea. The 1999 Pittsburgh Statement of Principles, for example, used the somewhat ambiguous formula "the spirit within us is eternal".

Along these lines, the concept of reward and punishment in the world to come

The world to come, age to come, heaven on Earth, and the Kingdom of God are eschatological phrases reflecting the belief that the current world or current age is flawed or cursed and will be replaced in the future by a better world, age, or p ...

was abolished as well. The only perceived form of retribution for the wicked, if any, was the anguish of their soul after death, and vice versa, bliss was the single accolade for the spirits of the righteous. Angels and heavenly hosts were also deemed a foreign superstitious influence, especially from early Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ont ...

sources, and denied.

Practice

Liturgy

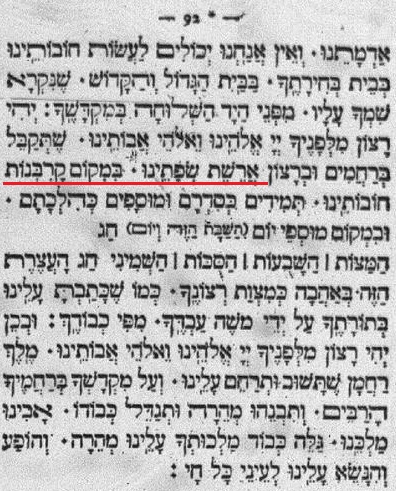

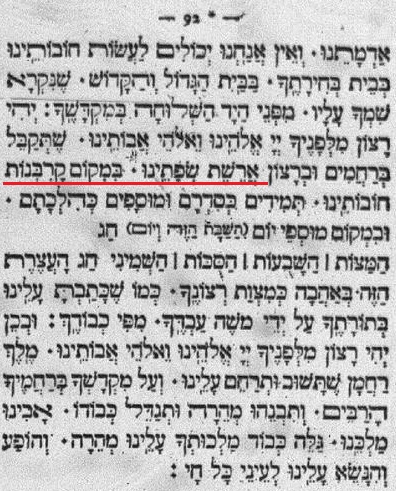

The first and primary field in which Reform convictions were expressed was that of prayer forms. From its beginning, Reform Judaism attempted to harmonize the language of petitions with modern sensibilities and what the constituents actually believed in. Jakob Josef Petuchowski, in his extensive survey of Progressive liturgy, listed several key principles that defined it through the years and many transformations it underwent. The prayers were abridged, whether by omitting repetitions, excising passages or reintroducing the ancienttriennial cycle

The Triennial cycle of Torah reading may refer to either

* The historical practice in ancient Israel by which the entire Torah was read in serial fashion over a three-year period, or

* The practice adopted by many Reform, Conservative, Reconstruct ...

for reading the Torah; vernacular segments were added alongside or instead of the Hebrew and Aramaic text, to ensure the congregants understood the petitions they expressed; and some new prayers were composed to reflect the spirit of changing times. But chiefly, liturgists sought to reformulate the prayerbooks and have them express the movement's theology. Blessings and passages referring to the coming of the Messiah, return to Zion, renewal of sacrificial practices, resurrection of the dead, reward and punishment and overt particularism of the People Israel were replaced, recast or excised altogether.

In its early stages, when Reform Judaism was more a tendency within unified communities in Central Europe than an independent movement, its advocates had to practice considerable moderation, lest they provoke conservative animosity. German prayerbooks often relegated the more contentious issues to the vernacular translation, treating the original text with great care and sometimes having problematic passages in small print and untranslated. When institutionalized and free of such constraints, it was able to pursue a more radical course. In American "Classical" or British Liberal prayerbooks, a far larger vernacular component was added and liturgy was drastically shortened, and petitions in discord with denominational theology eliminated.

"New Reform", both in the United States and in Britain and the rest of the world, is characterized by larger affinity to traditional forms and diminished emphasis on harmonizing them with prevalent beliefs. Concurrently, it is also more inclusive and accommodating, even towards beliefs that are officially rejected by Reform theologians, sometimes allowing alternative differing rites for each congregation to choose from. Thus, prayerbooks from the mid–20th century onwards incorporated more Hebrew, and restored such elements as blessing on phylacteries. More profound changes included restoration of the ''Gevorot'' benediction in the 2007 ''Mishkan T'filah

''Mishkan T'filah—A Reform Siddur'' is a siddur, prayer book prepared for Reform Judaism, Reform Jewish congregations around the world by the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR). ''Mishkan T'filah (משכן תפלה)'' is Hebrew for "Dw ...

'', with the optional "give life to all/revive the dead" formula. The CCAR stated this passage did not reflect a belief in Resurrection, but Jewish heritage. On the other extreme, the 1975 ''Gates of Prayer

''Gates of Prayer, the New Union Prayer Book'' (''GOP'') is a Reform Jewish siddur that was announced in October 1975 as a replacement for the 80-year-old '' Union Prayer Book'' (''UPB''), incorporating more Hebrew content and was updated to be m ...

'' substituted "the Eternal One" for "God" in the English translation (though not in the original), a measure that was condemned by several Reform rabbis as a step toward religious humanism.

Observance

During its formative era, Reform was oriented toward lesser ceremonial obligations. In 1846, the Breslau rabbinical conference abolished thesecond day of festivals

''Yom tov sheni shel galuyot'' ( he, יום טוב שני של גלויות), also called in short ''yom tov sheni'', means "the second festival day in the Diaspora", and is an important concept in halakha (Jewish law). The concept refers to the ...

; during the same years, the Berlin Reform congregation held prayers without blowing the Ram's Horn, phylacteries, mantles or head covering

Headgear, headwear, or headdress is the name given to any element of clothing which is worn on one's head, including hats, helmets, turbans and many other types. Headgear is worn for many purposes, including protection against the elements, d ...

, and held its Sabbath services on Sunday. In the late 19th and early 20th century, American "Classical Reform" often emulated Berlin on a mass scale, with many communities conducting prayers along the same style and having additional services on Sunday. An official rescheduling of Sabbath to Sunday was advocated by Kaufmann Kohler

Kaufmann Kohler (May 10, 1843 – January 28, 1926) was a German-born Jewish American biblical scholar and critic, theologian, Reform rabbi, and contributing editor to numerous articles of ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'' (1906).

Life and work

Kauf ...

for some time, though he retracted it eventually. Religious divorce was declared redundant and the civil one recognized as sufficient by American Reform in 1869, and in Germany by 1912; the laws concerning dietary

In nutrition, diet is the sum of food consumed by a person or other organism.

The word diet often implies the use of specific intake of nutrition for health or weight-management reasons (with the two often being related). Although humans are o ...

and personal purity, the priestly prerogatives, marital ordinances and so forth were dispensed with, and openly revoked by the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform The Pittsburgh Platform is a pivotal 1885 document in the history of the American Reform Movement in Judaism that called for Jews to adopt a modern approach to the practice of their faith. While it was never formally adopted by the Union of Americ ...

, which declared all ceremonial acts binding only if they served to enhance religious experience. From 1890, converts were no longer obligated to be circumcised. Similar policy was pursued by Claude Montefiore

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, also Goldsmid–Montefiore or just Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) was the intellectual founder of Anglo- Liberal Judaism and the founding president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a schola ...

's Jewish Religious Union, established at Britain in 1902. The Vereinigung für das Liberale Judentum in Germany, which was more moderate, declared virtually all personal observance voluntary in its 1912 guidelines.

"New Reform" saw the establishment and membership lay greater emphasis on the ceremonial aspects, after the former sterile and minimalist approach was condemned as offering little to engage in religion and encouraging apathy. Numerous rituals became popular again, often after being recast or reinterpreted, though as a matter of personal choice for the individual and not an authoritative obligation. Circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

or Letting of Blood for converts and newborn babies became virtually mandated in the 1980s; ablution

Ablution is the act of washing oneself. It may refer to:

* Ablution as hygiene

* Ablution as ritual purification

** Ablution in Islam:

*** Wudu, daily wash

*** Ghusl, bathing ablution

*** Tayammum, waterless ablution

** Ablution in Christianity

* ...

for menstruating women gained great grassroots popularity at the turn of the century, and some synagogues built mikveh

Mikveh or mikvah (, ''mikva'ot'', ''mikvoth'', ''mikvot'', or (Yiddish) ''mikves'', lit., "a collection") is a bath used for the purpose of ritual immersion in Judaism to achieve ritual purity.

Most forms of ritual impurity can be purif ...

s (ritual baths). A renewed interest in dietary laws (though by no means in the strict sense) also surfaced at the same decades, as were phylacteries, prayer shawls and head coverings. Reform is still characterized by having the least service attendance on average: for example, of those polled by Pew

A pew () is a long bench seat or enclosed box, used for seating members of a congregation or choir in a church, synagogue or sometimes a courtroom.

Overview

The first backless stone benches began to appear in English churches in the thi ...

in 2013, only 34% of registered synagogue members (and only 17% of all those who state affinity) attend services once a month and more.

The Proto-Reform movement did pioneer new rituals. In the 1810s and 1820s, the circles ( Israel Jacobson, Eduard Kley and others) that gave rise to the movement introduced confirmation ceremonies for boys and girls, in emulation of parallel Christian initiation rite. These soon spread outside the movement, though many of a more traditional leaning rejected the name "confirmation". In the "New Reform", Bar Mitzvah largely replaced it as part of the re-traditionalization, but many young congregants in the United States still perform one, often at Shavuot

(''Ḥag HaShavuot'' or ''Shavuos'')

, nickname = English: "Feast of Weeks"

, observedby = Jews and Samaritans

, type = Jewish and Samaritan

, begins = 6th day of Sivan (or the Sunday following the 6th day of Sivan in ...

. Confirmation for girls eventually developed into the Bat Mitzvah, now popular among all except strictly Orthodox Jews.

Some branches of Reform, while subscribing to its differentiation between ritual and ethics, chose to maintain a considerable degree of practical observance, especially in areas where a conservative Jewish majority had to be accommodated. Most Liberal communities in Germany maintained dietary standards and the like in the public sphere, both due to the moderation of their congregants and threats of Orthodox secession. A similar pattern characterizes the Movement for Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism (formally the Movement for Reform Judaism and known as Reform Synagogues of Great Britain until 2005) is one of the two World Union for Progressive Judaism–affiliated denominations in the United Kingdom. Reform is relatively ...

in Britain, which attempted to appeal to newcomers from the United Synagogue

The United Synagogue (US) is a union of British Orthodox Jewish synagogues, representing the central Orthodox movement in Judaism. With 62 congregations (including 7 affiliates and 1 associate, ), comprising 40,000 members, it is the largest s ...

, or to the IMPJ in Israel.Openness

Its philosophy of continuous revelation made Progressive Judaism, in all its variants, much more able to embrace change and new trends than any of the other major denominations. Reform Judaism is considered to be the first major Jewish denomination to adopt gender equality in religious life. As early as 1846, the Breslau conference announced that women must enjoy identical obligations and prerogatives in worship and communal affairs, though this decision had virtually no effect in practice. Lily Montagu, who served as a driving force behind British Liberal Judaism and WUPJ, was the first woman in recorded history to deliver a sermon at a synagogue in 1918, and set another precedent when she conducted a prayer two years later. Regina Jonas, ordained in 1935 by later chairman of the Vereinigung der liberalen Rabbiner Max Dienemann, was the earliest known female rabbi to officially be granted the title. In 1972, Sally Priesand was ordained byHebrew Union College

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, which made her America's first female rabbi ordained by a rabbinical seminary, and the second formally ordained female rabbi in Jewish history, after Regina Jonas. Reform also pioneered family seating, an arrangement that spread throughout American Jewry but was only applied in continental Europe after World War II. Egalitarianism in prayer became universally prevalent in the WUPJ by the end of the 20th century.

Religious inclusion for LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is a ...

people and ordination of LGBT rabbis were also pioneered by the movement. Intercourse between consenting adults was declared as legitimate by the Central Conference of American Rabbis

The Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), founded in 1889 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the principal organization of Reform rabbis in the United States and Canada. The CCAR is the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in the world. It ...

in 1977, and openly gay clergy were admitted by the end of the 1980s. Same-sex marriage was sanctioned by the end of the following decade. In 2015, the URJ adopted a Resolution on the Rights of Transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through tr ...

and Gender Non-Conforming People, urging clergy and synagogue attendants to actively promote tolerance and inclusion of such individuals.

American Reform, especially, turned action for social and progressive causes into an important part of religious commitment. From the second half of the 20th century, it employed the old rabbinic notion of ''Tikkun Olam

''Tikkun olam'' ( he, תִּיקּוּן עוֹלָם, , repair of the world) is a concept in Judaism, which refers to various forms of action intended to repair and improve the world.

In classical rabbinic literature, the phrase referred to le ...

'', "repairing the world", as a slogan under which constituents were encouraged to partake in various initiatives for the betterment of society. The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism

The Religious Action Center (RAC) is the political and legislative outreach arm of Reform Judaism in the United States. The Religious Action Center is operated under the auspices of the Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism, a joint body of ...

became an important lobby in service of progressive causes such as the rights of minorities. ''Tikkun Olam'' has become the central venue for active participation for many affiliates, even leading critics to negatively describe Reform as little more than a means employed by Jewish liberals to claim that commitment to their political convictions was also a religious activity and demonstrates fealty to Judaism. Dana Evan Kaplan

Dana Evan Kaplan (born October 29, 1960) is a Reform rabbi known for his writings on Reform Judaism and American Judaism. He has also written on other subjects, including American Jewish history and Jews in various diaspora communities. Kaplan ha ...

stated that "Tikkun Olam ''has incorporated only leftist, socialist-like elements. In truth, it is political, basically a mirror of the most radically leftist components of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

* Botswana Democratic Party

* Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*De ...

platform, causing many to say that Reform Judaism is simply 'the Democratic Party with Jewish holidays'.''" In Israel, the Religious Action Center

The Religious Action Center (RAC) is the political and legislative outreach arm of Reform Judaism in the United States. The Religious Action Center is operated under the auspices of the Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism, a joint body of ...

is very active in the judicial field, often using litigation both in cases concerning civil rights in general and the official status of Reform Judaism within the state, in particular.

Jewish identity

While opposed tointerfaith marriage

Interfaith marriage, sometimes called a "mixed marriage", is marriage between spouses professing different religions. Although interfaith marriages are often established as civil marriages, in some instances they may be established as a religiou ...

in principle, officials of the major Reform rabbinical organisation, the Central Conference of American Rabbis

The Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), founded in 1889 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the principal organization of Reform rabbis in the United States and Canada. The CCAR is the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in the world. It ...

(CCAR), estimated in 2012 that about half of their rabbis partake in such ceremonies. The need to cope with this phenomenon – 80% of all Reform-raised Jews in the United States wed between 2000 and 2013 were intermarried – led to the recognition of patrilineal descent

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

: all children born to a couple in which a single member was Jewish, whether mother or father, was accepted as a Jew on condition that they received corresponding education and committed themselves as such. Conversely, offspring of a Jewish mother only are not accepted if they do not demonstrate affinity to the faith. A Jewish status is conferred unconditionally only on the children of two Jewish parents.

This decision was taken by the British Liberal Judaism in the 1950s. The North American Union for Reform Judaism

The Union for Reform Judaism (URJ), known as the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC) until 2003, founded in 1873 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the congregational arm of Reform Judaism in North America. The other two arms established b ...

(URJ) accepted it in 1983, and the British Movement for Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism (formally the Movement for Reform Judaism and known as Reform Synagogues of Great Britain until 2005) is one of the two World Union for Progressive Judaism–affiliated denominations in the United Kingdom. Reform is relatively ...

affirmed it in 2015. The various strands also adopted a policy of embracing the intermarried and their spouses. British Liberals offer "blessing ceremonies" if the child is to be raised Jewish, and the MRJ allows its clergy to participate in celebration of civil marriage, though none allow a full Jewish ceremony with ''chupah

A ''chuppah'' ( he, חוּפָּה, pl. חוּפּוֹת, ''chuppot'', literally, "canopy" or "covering"), also huppah, chipe, chupah, or chuppa, is a canopy under which a Jewish couple stand during their wedding ceremony. It consists of a c ...

'' and the like. In American Reform, 17% of synagogue-member households have a converted spouse, and 26% an unconverted one. Its policy on conversion and Jewish status led the WUPJ into conflict with more traditional circles, and a growing number of its adherents are not accepted as Jewish by either the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization ...

or the Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

. Outside North America and Britain, patrilineal descent was not accepted by most. As in other fields, small WUPJ affiliates are less independent and often have to deal with more conservative Jewish denominations in their countries, such as vis-à-vis the Orthodox rabbinate in Israel or continental Europe.

Organization and demographics

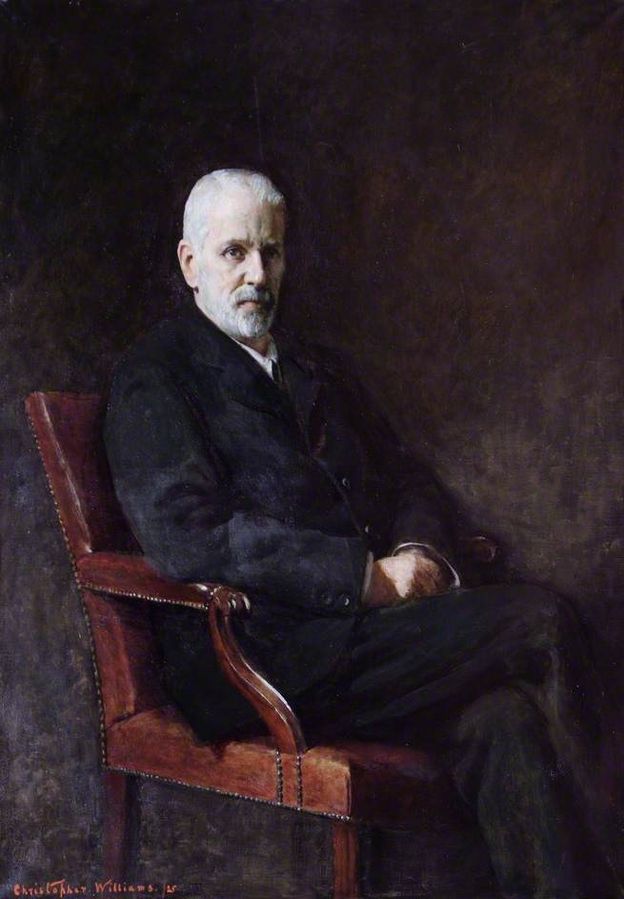

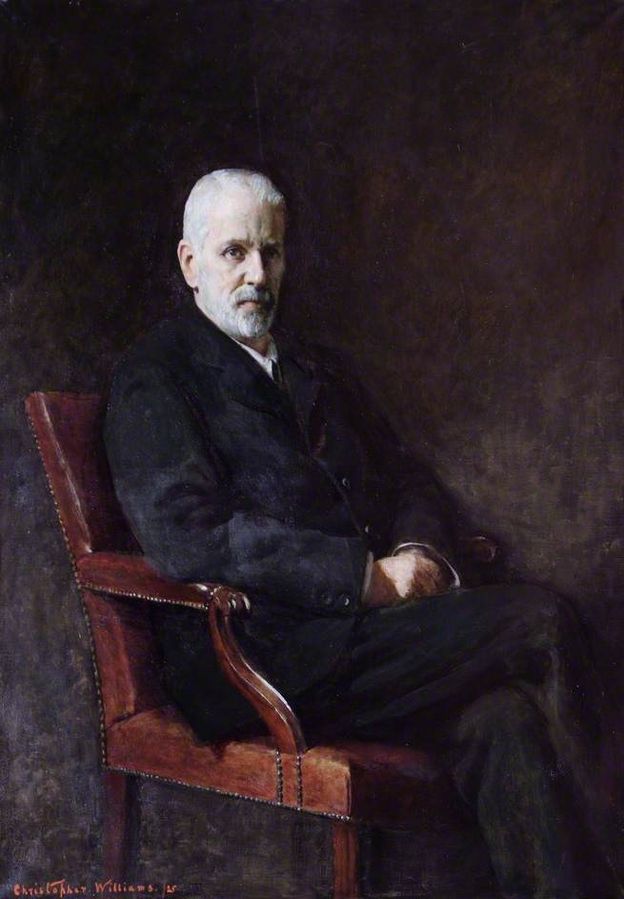

The term "Reform" was first applied institutionally – not generically, as in "for reform" – to the Berlin Reformgemeinde (Reform Congregation), established in 1845. Apart from it, most German communities that were oriented in that direction preferred the more ambiguous "Liberal", which was not exclusively associated with Reform Judaism. It was more prevalent as an appellation for the religiously apathetic majority among German Jews, and also to all rabbis who were not clearly Orthodox (including the rival Positive-Historical School). The title "Reform" became much more common in the United States, where an independent denomination under this name was fully identified with the religious tendency. However, Isaac Meyer Wise suggested in 1871 that "Progressive Judaism" was a better epithet. When the movement was institutionalized in Germany between 1898 and 1908, its leaders chose "Liberal" as self-designation, founding the Vereinigung für das Liberale Judentum. In 1902,Claude Montefiore

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, also Goldsmid–Montefiore or just Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) was the intellectual founder of Anglo- Liberal Judaism and the founding president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a schola ...

termed the doctrine espoused by his new Jewish Religious Union as "Liberal Judaism", too, though it belonged to the more radical part of the spectrum in relation to the German one.

In 1926, British Liberals, American Reform and German Liberals consolidated their worldwide movement – united in affirming tenets such as progressive revelation, supremacy of ethics above ritual and so forth – at a meeting held in London. Originally carrying the provisional title "International Conference of Liberal Jews", after deliberations between "Liberal", "Reform" and "Modern", it was named World Union for Progressive Judaism

The World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ) is the international umbrella organization for the various branches of Reform, Liberal and Progressive Judaism, as well as the separate Reconstructionist Judaism. The WUPJ is based in 40 countries ...

on 12 July, at the conclusion of a vote. The WUPJ established further branches around the planet, alternatively under the names "Reform", "Liberal" and "Progressive". In 1945, the Associated British Synagogues (later Movement for Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism (formally the Movement for Reform Judaism and known as Reform Synagogues of Great Britain until 2005) is one of the two World Union for Progressive Judaism–affiliated denominations in the United Kingdom. Reform is relatively ...

) joined as well. In 1990, Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism is a Jewish movement that views Judaism as a progressively evolving civilization rather than a religion, based on concepts developed by Mordecai Kaplan (1881–1983). The movement originated as a semi-organized stream w ...

entered the WUPJ as an observer. Espousing another religious worldview, it became the only non-Reform member. The WUPJ claims to represent a total of at least 1.8 million people – these figures do not take into account the 2013 PEW survey, and rely on the older URJ estimate of a total of 1.5 million presumed to have affinity, since updated to 2.2 million – both registered synagogue members and non-affiliates who identify with it.

Worldwide, the movement is mainly centered in North America. The largest WUPJ constituent by far is the Union for Reform Judaism

The Union for Reform Judaism (URJ), known as the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC) until 2003, founded in 1873 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the congregational arm of Reform Judaism in North America. The other two arms established b ...

(until 2003: Union of American Hebrew Congregations) in the United States and Canada. As of 2013, the Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan American think tank (referring to itself as a "fact tank") based in Washington, D.C.

It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the wo ...

survey calculated it represented about 35% of all 5.3 million Jewish adults in the U.S., making it the single most numerous Jewish religious group in the country. Steven M. Cohen deduced there were 756,000 adult Jewish synagogue members – about a quarter of households had an unconverted spouse (according to 2001 findings), adding some 90,000 non-Jews and making the total constituency roughly 850,000 – and further 1,154,000 "Reform-identified non-members" in the United States. There are also 30,000 in Canada.Steven M. Cohen"As Reform Jews Gather, Some Good News in the Numbers"

''

The Forward

''The Forward'' ( yi, פֿאָרווערטס, Forverts), formerly known as ''The Jewish Daily Forward'', is an American news media organization for a Jewish American audience. Founded in 1897 as a Yiddish-language daily socialist newspaper, ...

'', 5 November 2015. Steven M. Cohen"Members and Motives: Who Joins American Jewish Congregations and Why"

, S3K Report, Fall 2006 Based on these, the URJ claims to represent 2.2 million people. It has 845 congregations in the U.S. and 27 in Canada, the vast majority of the 1,170 affiliated with the WUPJ that are not Reconstructionist. Its rabbinical arm is the

Central Conference of American Rabbis

The Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), founded in 1889 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the principal organization of Reform rabbis in the United States and Canada. The CCAR is the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in the world. It ...

, with some 2,300 member rabbis, mainly trained in Hebrew Union College

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

. As of 2015, the URJ was led by President Rabbi Richard Jacobs, and the CCAR headed by Rabbi Denise Eger

Denise Leese Eger (born March 14, 1960) is an American Reform rabbi. In March 2015, she became president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in North America; she was the first openly gay ...

.

The next in size, by a wide margin, are the two British WUPJ-affiliates. In 2010, the Movement for Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism (formally the Movement for Reform Judaism and known as Reform Synagogues of Great Britain until 2005) is one of the two World Union for Progressive Judaism–affiliated denominations in the United Kingdom. Reform is relatively ...

and Liberal Judaism respectively had 16,125 and 7,197 member households in 45 and 39 communities, or 19.4% and 8.7% of British Jews registered at a synagogue. Other member organizations are based in forty countries around the world. They include the Union progressiver Juden in Deutschland, which had some 4,500 members in 2010 and incorporates 25 congregations, one in Austria; the Nederlands Verbond voor Progressief Jodendom

The Nederlands Verbond voor Progressief Jodendom (Dutch Union for Progressive Judaism; until 2006: Verbond voor Liberaal-Religieuze Joden in Nederland, Union for Liberal-Religious Jews in the Netherlands) is the umbrella organisation for Progres ...

, with 3,500 affiliates in 10 communities; the 13 Liberal synagogues in France; the Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism

The Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism (IMPJ; he, התנועה הרפורמית – יהדות מתקדמת בישראל) is the organizational branch of Progressive Judaism in Israel, and a member organization of the World Union ...

(5,000 members in 2000, 35 communities); the Movement for Progressive Judaism (Движение прогрессивного Иудаизма) in the CIS and Baltic States

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

, with 61 affiliates in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

, Ukraine and Belarus and several thousands of regular constituents; and many other, smaller ones.

History

Beginnings

With the advent of

With the advent of Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It i ...

and acculturation

Acculturation is a process of social, psychological, and cultural change that stems from the balancing of two cultures while adapting to the prevailing culture of the society. Acculturation is a process in which an individual adopts, acquires an ...

in Central Europe during the late 18th century, and the breakdown of traditional patterns and norms, the response Judaism should offer to the changed circumstances became a heated concern. Radical, second-generation Berlin ''maskilim

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Eur ...

'' (Enlightened), like Lazarus Bendavid

Lazarus Bendavid (18 October 1762, in Berlin – 28 March 1832, in Berlin) was a German mathematician and philosopher known for his exposition of Kantian philosophy.

Biography

Bendavid was a Jewish Kantian philosopher. After his graduation from ...

and David Friedländer

David Friedländer (sometimes spelled Friedlander; 16 December 1750, Königsberg – 25 December 1834, Berlin) was a German banker, writer and communal leader.

Life

Friedländer settled in Berlin in 1771. As the son-in-law of the rich banker D ...

, proposed to reduce it to little above Deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of ...

or allow it to dissipate. A more palatable course was the reform of worship in synagogues, making it more attractive to a Jewish public whose aesthetic and moral taste became attuned to that of Christian surroundings. The first considered to have implemented such a course was the Amsterdam Ashkenazi congregation, Adath Jessurun. In 1796, emulating the local Sephardic

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

custom, it omitted the " Father of Mercy" prayer, beseeching God to take revenge upon the gentiles. The short-lived Adath Jessurun employed fully traditional argumentation to legitimize its actions, but is often regarded a harbinger by historians.

A relatively thoroughgoing program was adopted by Israel Jacobson, a philanthropist from the Kingdom of Westphalia. Faith and dogma were eroded for decades both by Enlightenment criticism and apathy, but Jacobson himself did not bother with those. He was interested in decorum, believing its lack in services was driving the young away. Many of the aesthetic reforms he pioneered, like a regular vernacular sermon on moralistic themes, would be later adopted by the modernist Orthodox. On 17 July 1810, he dedicated a synagogue in Seesen

Seesen is a town and municipality in the district of Goslar, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the northwestern edge of the Harz mountain range, approx. west of Goslar.

History

The Saxon settlement of ''Sehusa'' was first mentioned ...

that employed an organ and a choir during prayer and introduced some German liturgy. While Jacobson was far from full-fledged Reform Judaism, this day was adopted by the movement worldwide as its foundation date. The Seesen temple – a designation quite common for prayerhouses at the time; "temple" would later become, somewhat misleadingly (and not exclusively), identified with Reform institutions via association with the elimination of prayers for the Jerusalem Temple – closed in 1813. Jacobson moved to Berlin and established a similar one, which became a hub for like-minded individuals. Though the prayerbook used in Berlin did introduce several deviations from the received text, it did so without an organizing principle. In 1818, Jacobson's acquaintance Edward Kley founded the Hamburg Temple

The Hamburg Temple (german: link=no, Israelitischer Tempel) was the first permanent Reform synagogue and the first ever to have a Reform prayer rite. It operated in Hamburg ( Germany) from 1818 to 1938. On 18 October 1818 the Temple was inaugurate ...

. Here, changes in the rite were eclectic no more and had severe dogmatic implications: prayers for the restoration of sacrifices by the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashia ...

and Return to Zion

The return to Zion ( he, שִׁיבָת צִיּוֹן or שבי ציון, , ) is an event recorded in Ezra–Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah—subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire—were freed from th ...

were quite systematically omitted. The Hamburg edition is considered the first comprehensive Reform liturgy.

While Orthodox protests to Jacobson's initiatives had been scant, dozens of rabbis throughout Europe united to ban the Hamburg Temple. The Temple's leaders cited canonical sources to argue in favor of their reforms, but their argumentation did not resolve the intense controversy the Hamburg disputes generated. The Temple garnered some support, most notably in Aaron Chorin of Arad, a prominent but controversial rabbi and an open supporter of the Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Eur ...

, the European Jewish enlightenment movement. Chorin, however, would later publicly retract his enthusiastic support under pressure, stating that he had been unaware of the removal of key prayers from the liturgy, and maintaining his belief in the traditional Jewish doctrine of the personal Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashia ...

and the restoration of the Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temple ...

and its sacrifices.

The massive Orthodox reaction halted the advance of early Reform, confining it to the port city for the next twenty years. As acculturation spread throughout Central Europe, synchronized with the breakdown of traditional society and growing religious laxity, many synagogues introduced aesthetic modifications, such as replacing largely Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the center ...

ic discources with edifying sermons in the vernacular, and promoting an atmosphere more akin to church services. Yet these changes and others, including the promotion of secular higher education for rabbis, still generated controversy, and remained largely inconsistent and lacking in coherent ideology. One of the first to adopt such modifications was Hamburg's own Orthodox community, under the newly appointed modern Rabbi Isaac Bernays

Isaac Bernays ( , , ; 29 September 1792 – 1 May 1849) was Chief Rabbi in Hamburg.

Life

Bernays was born in Weisenau (now part of Mainz). He was the son of Jacob Gera, a boarding house keeper at Mainz, and an elder brother of Adolphus Bernays. ...

. The less strict but traditional Isaac Noah Mannheimer

Isaac Noah Mannheimer (October 17, 1793, Copenhagen – March 17, 1865, Vienna) was a Jewish preacher.

Biography

The son of a ''chazzan'', he began the study of the Talmud at an early age, though not to the neglect of secular studies. On completi ...

of the Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

Stadttempel

The Stadttempel ( en, City Prayer House), also called the Seitenstettengasse Temple, is the main synagogue of Vienna, Austria. It is located in the Innere Stadt 1st district, at Seitenstettengasse 4.

History

The synagogue was constructed from 182 ...

and Michael Sachs

Michael Yechiel Sachs (; 3 September 1808 – 31 January 1864) was a Prussian rabbi from Groß-Glogau, Silesia.

Life

He was one of the first Jewish graduates from the modern universities, earning a Ph.D. degree in 1836. He was appointed Rabbi i ...

in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a tempera ...

, set the pace for most of Europe. They significantly altered custom, but wholly avoided dogmatic issues or overt injury to Jewish Law.

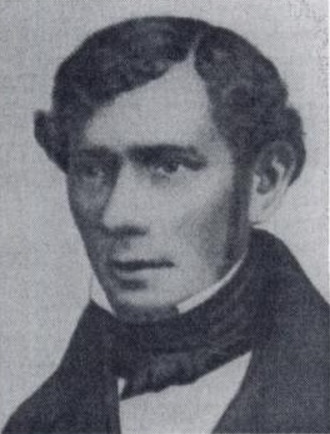

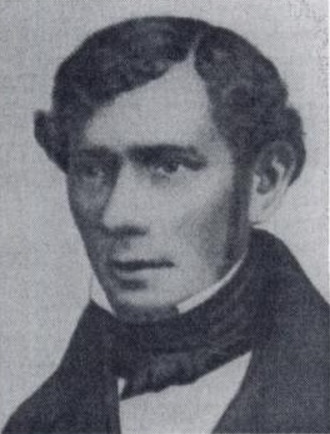

An isolated, yet much more radical step in the same direction as Hamburg's, was taken across the ocean in 1824. The younger congregants in the Charleston synagogue " Beth Elohim" were disgruntled by present conditions and demanded change. Led by

An isolated, yet much more radical step in the same direction as Hamburg's, was taken across the ocean in 1824. The younger congregants in the Charleston synagogue " Beth Elohim" were disgruntled by present conditions and demanded change. Led by Isaac Harby Isaac Harby (1788–1828), from Charleston, South Carolina, was an early 19th-century teacher, playwright, literary critic, journalist, newspaper editor, and advocate of reforms in Judaism. His ideas were some of the precedents behind the developmen ...

and other associates, they formed their own prayer group, "The Reformed Society of Israelites". Apart from strictly aesthetic matters, like having sermons and synagogue affairs delivered in English, rather than Middle Spanish (as was customary among Western Sephardim

Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also called Western Sephardim, Iberian Jews, or Peninsular Jews, are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews who are largely descended from Jews who lived as New Christians in the Iberian Peninsula during the ...

), they had almost their entire liturgy solely in the vernacular, in a far greater proportion compared to the Hamburg rite. And chiefly, they felt little attachment to the traditional Messianic doctrine and possessed a clearly heterodox religious understanding. In their new prayerbook, authors Harby, Abram Moïse and David Nunes Carvalho unequivocally excised pleas for the restoration of the Jerusalem Temple; during his inaugural address on 21 November 1825, Harby stated their native country was their only Zion, not "some stony desert", and described the rabbis of old as "Fabulists and Sophists... Who tortured the plainest precepts of the Law into monstrous and unexpected inferences". The Society was short-lived, and they merged back into Beth Elohim in 1833. As in Germany, the reformers were laymen, operating in a country with little rabbinic presence.

Consolidation in German lands

In the 1820s and 1830s, philosophers like

In the 1820s and 1830s, philosophers like Solomon Steinheim

Solomon Ludwig (Levy) Steinheim (pseudonym: ''Abadjah Ben Amos''; 1789–1866) was a German physician, poet, and philosopher.

Biography

Steinheim was born on 6 August 1789 in Altona (according to some authorities, in Bruchhausen, Westphalia ...

imported German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionar ...

into the Jewish religious discourse, attempting to draw from the means it employed to reconcile Christian faith and modern sensibilities. But it was the new scholarly, critical Science of Judaism (''Wissenschaft des Judentums

"''Wissenschaft des Judentums''" (Literally in German the expression means "Science of Judaism"; more recently in the US it started to be rendered as "Jewish Studies" or "Judaic Studies," a wide academic field of inquiry in American Universities) ...

'') that became the focus of controversy. Its proponents vacillated whether and to what degree it should be applied against the contemporary plight. Opinions ranged from the strictly Orthodox Azriel Hildesheimer

Azriel Hildesheimer (also Esriel and Israel, yi, עזריאל הילדעסהיימער; 11 May 1820 – 12 July 1899) was a German rabbi and leader of Orthodox Judaism. He is regarded as a pioneering moderniser of Orthodox Judaism in Germany an ...

, who subjugated research to the predetermined sanctity of the texts and refused to allow it practical implication over received methods; via the Positive-Historical Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

, who did not deny ''Wissenschaft'' a role, but only in deference to tradition, and opposed analysis of the Pentateuch