Red Stick War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the

Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1985, pp. 38-39, accessed 11 September 2011 Leaders of the Lower Creek towns in present-day Georgia included Bird Tail King (''Fushatchie Mico'') of Cusseta, Little Prince (''Tustunnuggee Hopoi'') of Broken Arrow, and

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and along the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

. The major conflicts of the war took place between state militia units and the "Red Stick

Red Sticks (also Redsticks, Batons Rouges, or Red Clubs), the name deriving from the red-painted war clubs of some Native American Creeks—refers to an early 19th-century traditionalist faction of these people in the American Southeast. Made ...

" Creeks. The United States government formed an alliance with the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

Nation and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

Nation (the traditional enemies of the Creeks), along with the remaining Creeks to put the rebellion down.

According to historian John K. Mahon, the Creek War "was as much a civil war among Creeks as between red and white, and it pointed up the separation of Creeks and Seminoles". The war was also part of the centuries-long American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

. It is usually considered part of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

because it was influenced by Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion was a conflict between the United States and Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh in the Indiana Territory. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Ha ...

in the Old Northwest

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, was concurrent with the American-British portion of the war and involved many of the same participants, and because the Red Sticks had sought British support and aided Admiral Cochrane's advance towards New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

.

The Creek War began as a conflict within the Creek Confederation, but local militia units quickly became involved. British traders in Florida as well as the Spanish government provided the Red Sticks with arms and supplies because of their shared interest in preventing the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

expansion of the United States

The United States of America was created on July 4, 1776, with the U.S. Declaration of Independence of thirteen British colonies in North America. In the Lee Resolution two days prior, the colonies resolved that they were free and independent ...

into their areas. The war effectively ended with the Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

(August 1814), when General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

forced the Creek confederacy to surrender more than 21 million acres in what is now southern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and central Alabama.Green (1998), ''Politics of Removal'', p. 43

Background

Creek militancy was a response to increasing United States cultural and territorial encroachment into their traditional lands. But the war's alternate designation as "the Creek Civil War" comes from the divisions within the tribe over cultural, political, economic, and geographic matters. At the time of the Creek War, the Upper Creeks controlled the Coosa, Tallapoosa, andAlabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

Rivers that lead to Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

, while the Lower Creeks controlled the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

, which flows into Apalachicola Bay Apalachicola may refer to:

* Apalachicola people, a group of Native Americans who lived along the Apalachicola River in present-day Florida

Places

* Apalachicola, Florida

*Apalachicola River

* Apalachicola Bay

* Apalachicola National Forest

* Apa ...

. The Lower Creek were trading partners with the United States and, unlike the Upper Creeks, had adopted more of their cultural practices.

Territorial conflict

The provinces ofEast

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

, governed by Spanish and British firms like Panton, Leslie, and Co., provided most of the European trading goods into Creek country. Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

and Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

, in Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

, controlled the outlets of the U.S. Mississippi Territory's rivers.

Territorial conflicts between France, Spain, Britain, and the United States along the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

that had previously helped the Creeks to maintain control over most of the United States' southwestern territory had shifted dramatically due to the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the West Florida Rebellion, and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. This made long-standing intra-Creek trade and political alliances more tenuous than ever.

In the Treaty of New York (1790)

The Treaty of New York was a treaty signed in 1790 between leaders of the Muscogee and U.S. Secretary of War Henry Knox, who served in the presidential administration of George Washington.

A failed 1789 attempt at a treaty between the United S ...

, Treaty of Colerain

The Treaty of Colerain was signed at St. Marys, Georgia in Camden County, Georgia, by Benjamin Hawkins, George Clymer, and Andrew Pickens (congressman), Andrew Pickens for the United States and representatives of the Creek people, Creek Nation, for ...

(1796), Treaty of Fort Wilkinson (1802), and Treaty of Washington (1805), the Creek ceded parts of their Georgia territory east of the Ocmulgee River

The Ocmulgee River () is a western tributary of the Altamaha River, approximately 255 mi (410 km) long, in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the westernmost major tributary of the Altamaha.

. In 1804, the United States claimed the city of Mobile under the Mobile Act. The 1805 treaty with the Creek also allowed the creation of the Federal Road that linked Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

to the newly acquired port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

city of New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, which partially stretched through Creek territories.

During and after the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, the United States wished to maintain the Indian Line

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by George III of the United Kingdom, King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred New France, French territory ...

which had been established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

. The Indian Line created a boundary for colonial settlement in order to prevent illegal encroachment into Indian lands, and also helped the U.S. government maintain control over Indian trade. Still, traders and settlers often violated the terms of the treaties establishing the Indian Line, and frontier settlement by colonists in Indian lands was one of the arguments the United States used to expand its territory.

These increasing territorial grabs westward into Creek territory (which included parts of Spanish Florida), coupled with the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

(which neither the British nor the Spanish recognized at the time), compelled the British and Spanish governments to strengthen existing alliances with the Creek. In 1810, following the occupation of Baton Rouge during the West Florida Rebellion, the United States sent an expeditionary force to occupy Mobile. As a result, Mobile was jointly occupied by weak detachments of American and Spanish soldiers until Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John Armstrong ordered General James Wilkinson to force the Spanish to turn over control of the city in February 1813.

The Patriot Army captured parts of East Florida from 1811–1815. After Fort Charlotte was surrendered in April, the Spanish focused on protecting Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

from the United States. The Spanish decided to support the Creek in an attack on the United States and in defense of their homeland, but were greatly hindered by their weak position in the Floridas and lack of supplies even for their own army.

Cultural assimilation and religious revival

The splintering of the Creek peoples along progressive and nativist lines had roots dating back to the eighteenth century, but came to a head after 1811.Thrower. "Casualties and Consequences of the Creek War," in Rethinking Tohopeka, 12. Red Stick militancy was a response to the economic and cultural crises in Creek society caused by the adoption ofWestern

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

trade goods and culture. From the sixteenth century, the Creek had formed successful trade alliances with European empires, but the drastic fall in the price of deerskin from 1783 to 1793 made it more difficult for individuals to repay their debt, while at the same time the assimilation process made American goods more necessary. The Red Sticks particularly resisted the civilization programs administered by the U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754June 6, 1816) was an American planter, statesman and a U.S. Indian agent He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite ...

, who had stronger alliances among the towns of the Lower Creek. Some of the "progressive" Creek began to adopt American farming practices as their game disappeared, and as more Anglo settlers assimilated into Creek towns and families.Michael D. Green, ''The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis''Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1985, pp. 38-39, accessed 11 September 2011 Leaders of the Lower Creek towns in present-day Georgia included Bird Tail King (''Fushatchie Mico'') of Cusseta, Little Prince (''Tustunnuggee Hopoi'') of Broken Arrow, and

William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth cen ...

(''Tunstunuggee Hutkee'', White Warrior) of Coweta

Coweta is a city in Wagoner County, Oklahoma, United States, a suburb of Tulsa. As of 2010, its population was 9,943. Part of the Creek Nation in Indian Territory before Oklahoma became a U.S. state, the town was first settled in 1840.removal to be the only alternative to the assimilation of native peoples into Western culture. The Creeks, on the other hand, blended their own culture with adopted trade goods and political terms, and had no intention of abandoning their land.

The Americanization of the Creeks was more prevalent in western Georgia among the Lower Creeks than in Upper Creek towns, and came from internal and external processes. The U.S. government's and Benjamin Hawkins' pressure on the Creeks to assimilate stood in contrast to the more natural blending of cultures that came from a long tradition of cohabitation and cultural appropriation, beginning with white traders in Indian country.

The

Creeks who did not support the war became targets for the prophets and their followers, and began to be murdered in their sleep or burned alive. Warriors of the prophets' parties also began to attack the property of their enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock. The first major offensive of the civil war was the Red Stick attack on the Upper Creek town, and seat of the council, at

Creeks who did not support the war became targets for the prophets and their followers, and began to be murdered in their sleep or burned alive. Warriors of the prophets' parties also began to attack the property of their enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock. The first major offensive of the civil war was the Red Stick attack on the Upper Creek town, and seat of the council, at

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

leader Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

came to the area to encourage the peoples to join his movement to throw the Americans out of Native American territories. Previously, he had united tribes in the Northwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

(Ohio and related territories) to fight against U.S. settlers after the War for Independence. In 1811, Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa

Tenskwatawa (also called Tenskatawa, Tenskwatawah, Tensquatawa or Lalawethika) (January 1775 – November 1836) was a Native American religious and political leader of the Shawnee tribe, known as the Prophet or the Shawnee Prophet. He was a ...

attended the annual Creek council at Tukabatchee

Tukabatchee or Tuckabutche ( Creek: ''Tokepahce'' ) is one of the four mother towns of the Muscogee Creek confederacy.Isham, Theodore and Blue Clark"Creek (Mvskoke)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' ...

. Tecumseh delivered an hour-long speech to an audience of 5,000 Creeks as well as an American delegation including Hawkins. Although the Americans dismissed Tecumseh as non-threatening, his message of resistance to Anglo encroachment was well received among Creek and Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

, especially among more conservative and traditional elders and young men.

Mobilization of recruits to Tecumseh's cause was bolstered by the Great Comet of 1811

The Great Comet of 1811, formally designated C/1811 F1, is a comet that was visible to the naked eye for around 260 days, the longest recorded period of visibility until the appearance of Comet Hale–Bopp in 1997. In October 1811, at its bright ...

and the New Madrid earthquakes

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

of 1811–12, which were taken as evidence of Tecumseh's supernatural powers. The war party rallied around prophets who had traveled with Tecumseh and remained with the Creek, influencing newly converted Creek religious leaders.Owsley, 14-15. Peter McQueen

Peter McQueen (c. 1780 – 1820) was a Creek chief, prophet, trader and warrior from ''Talisi'' ( Tallassee, among the Upper Towns in present-day Alabama.) He was one of the young men known as Red Sticks, who became a prophet for expulsion of ...

of ''Talisi'' (now Tallassee, Alabama

Tallassee (pronounced ) is a city on the Tallapoosa River, located in both Elmore and Tallapoosa counties in the U.S. state of Alabama. At the 2020 census, the population was 4,763. It is home to a major hydroelectric power plant at Thurlow ...

); Josiah Francis (Hillis Hadjo) (Francis the Prophet) of '' Autaga'', a Koasati

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the territor ...

town; and High-head Jim (''Cusseta Tustunnuggee'') and Paddy Walsh, both Alabamas, were among the spiritual leaders responding to rising concerns and the prophetic message. The militant faction of Creek stood in opposition of the Creek Confederacy Council's official policies, particularly in regard to foreign relations with the United States. The rising war party began to be called " Red Sticks" at this timein Creek culture, red 'sticks' or clubs symbolize war, while white sticks represent peace.

Course of the war

Creeks who did not support the war became targets for the prophets and their followers, and began to be murdered in their sleep or burned alive. Warriors of the prophets' parties also began to attack the property of their enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock. The first major offensive of the civil war was the Red Stick attack on the Upper Creek town, and seat of the council, at

Creeks who did not support the war became targets for the prophets and their followers, and began to be murdered in their sleep or burned alive. Warriors of the prophets' parties also began to attack the property of their enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock. The first major offensive of the civil war was the Red Stick attack on the Upper Creek town, and seat of the council, at Tuckabatchee

Tukabatchee or Tuckabutche ( Creek: ''Tokepahce'' ) is one of the four mother towns of the Muscogee Creek confederacy.Isham, Theodore and Blue Clark"Creek (Mvskoke)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' ...

on July 22, 1813.

In Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, a war party of "friendly" Creek organized under William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth cen ...

, Big Warrior, and Little Prince attacked 150 Uchee

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th c ...

warriors who were traveling to meet up with Red Stick Creeks in the Mississippi Territory. After this offensive in the beginning of October 1813, the party burned a number of Red Stick towns before retiring to Coweta

Coweta is a city in Wagoner County, Oklahoma, United States, a suburb of Tulsa. As of 2010, its population was 9,943. Part of the Creek Nation in Indian Territory before Oklahoma became a U.S. state, the town was first settled in 1840.Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754June 6, 1816) was an American planter, statesman and a U.S. Indian agent He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite ...

did not believe that the disruption in the Creek Nation or the increasing war dances were a cause for concern. But in February 1813, a small war party of Red Sticks, led by Little Warrior, were returning from Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

when they killed two families of settlers along the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. Hawkins demanded that the Creek turn over Little Warrior and his six companions, the standard operating procedure between the nations up to that point.

The first clashes between the Red Sticks and United States forces occurred on July 27, 1813. A group of territorial militia intercepted a party of Red Sticks returning from Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

, where they had acquired arms from the Spanish governor at Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. The Red Sticks escaped and the soldiers looted what they found. Seeing the Americans looting, the Creek regrouped and attacked and defeated the Americans. The Battle of Burnt Corn

The Battle of Burnt Corn, also known as the Battle of Burnt Corn Creek, was an encounter between United States armed forces and Creek (people), Creek Indians that took place July 27, 1813 in present-day southern Alabama. The battle was part of th ...

, as the exchange became known, broadened the Creek Civil War to include American forces.

Chiefs Peter McQueen

Peter McQueen (c. 1780 – 1820) was a Creek chief, prophet, trader and warrior from ''Talisi'' ( Tallassee, among the Upper Towns in present-day Alabama.) He was one of the young men known as Red Sticks, who became a prophet for expulsion of ...

and William Weatherford

William Weatherford, also known after his death as Red Eagle (ca. 1765 – March 24, 1824), was a Creek chief of the Upper Creek towns who led many of the Red Sticks actions in the Creek War (1813–1814) against Lower Creek towns and against ...

led an attack on Fort Mims, north of Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

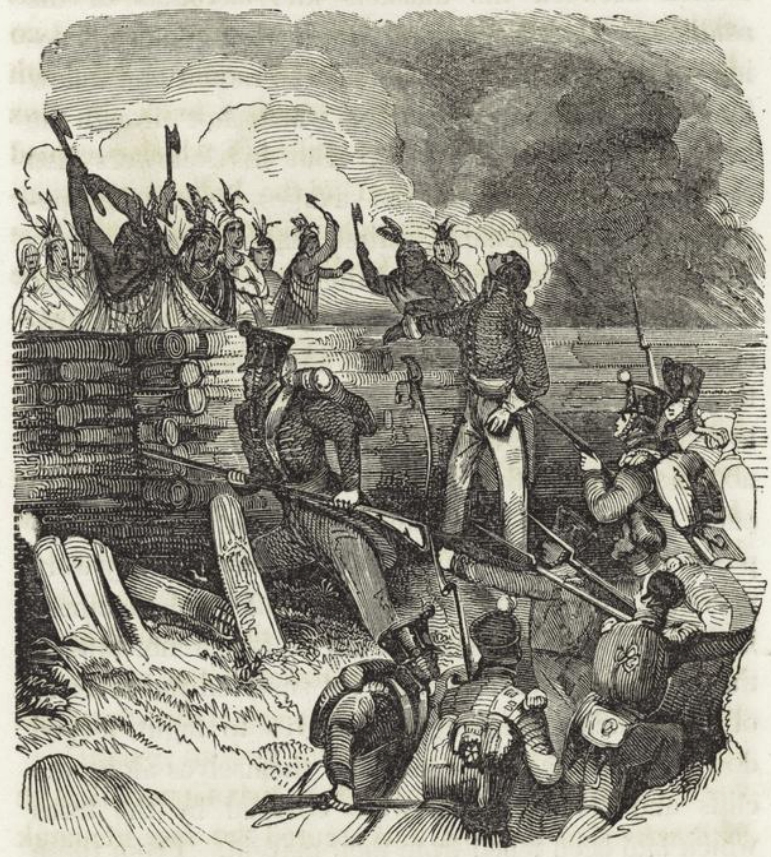

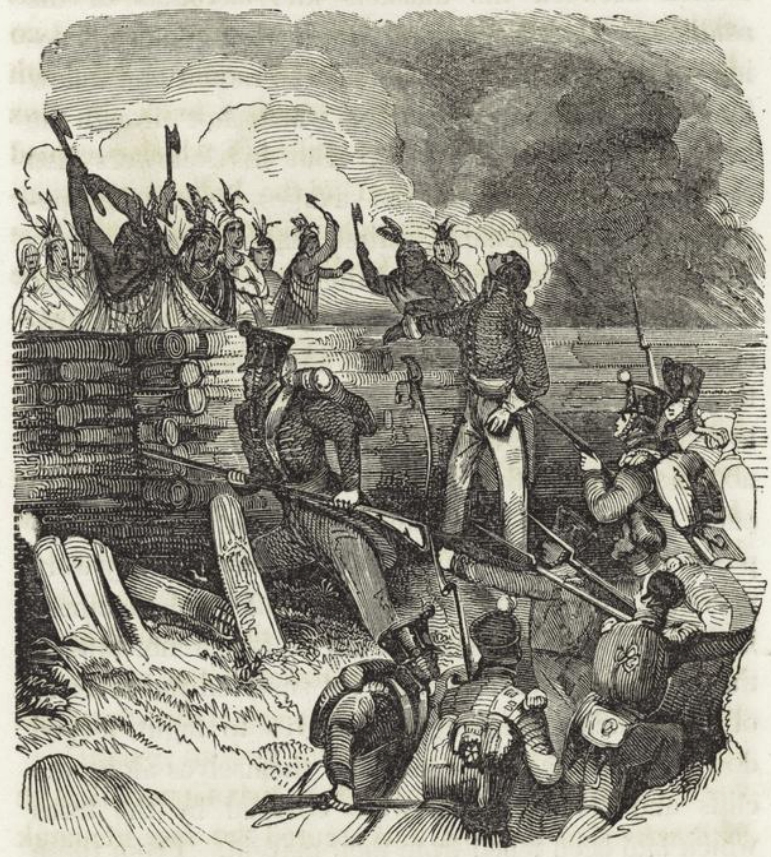

, on August 30, 1813. The Red Sticks' goal was to strike at mixed-blood Creek of the Tensaw settlement who had taken refuge at the fort. The warriors attacked the fort and killed a total of 400 to 500 people, including women and children and numerous white settlers. The attack became known as the Fort Mims Massacre and became a rallying cause for American militia.

The Red Sticks subsequently attacked other forts in the area, including Fort Sinquefield

Fort Sinquefield is the historic site of a wooden stockade fortification in Clarke County, Alabama, near the modern town of Grove Hill. It was built by early Clarke County pioneers as protection during the Creek War and was attacked in 1813 by ...

. Panic spread among settlers throughout the Southwestern frontier, and they demanded U.S. government intervention. Federal forces were busy fighting the British and Northern Woodland tribes, led by the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

chief Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

in the Northwest. Affected states called up militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s to deal with the threat.

After the Battle of Burnt Corn, U.S. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of th ...

John Armstrong notified General Thomas Pinckney, Commander of the 6th Military District, that the U.S. was prepared to take action against the Creek Confederacy. Furthermore, if Spain were found to be supporting the Creeks, an assault on Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

would ensue.

Brigadier General Ferdinand Claiborne

Ferdinand Leigh Claiborne (March 9, 1772 - March 22, 1815) was an American military officer most notable for his command of the militia of the Mississippi Territory during the Creek War and the War of 1812.

Early life

Born in Sussex County, Vir ...

, a militia commander in the Mississippi Territory, was concerned about the weakness of his sector on the western border of the Creek territory, and advocated preemptive strikes. But Major General Thomas Flourney, commander of 7th Military District, refused his requests. He intended to carry out a defensive American strategy. Meanwhile, settlers in that region sought refuge in blockhouses.

The Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

legislature authorized Governor Willie Blount

Willie Blount (April 18, 1768September 10, 1835) was an American politician who served as the third Governor of Tennessee from 1809 to 1815. Blount's efforts to raise funds and soldiers during the War of 1812 earned Tennessee the nickname, "Volu ...

to raise 5,000 militia for a three-month tour of duty. Blount called out a force of 2,500 West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions (Tennessee), Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee River, Tennessee and Miss ...

men under Colonel Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

to "repel an approaching invasion ... and to afford aid and relief to ... Mississippi Territory". He also summoned a force of 2,500 from East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

under Major General John Alexander Cocke

John Alexander Cocke (December 28, 1772February 16, 1854) was an American politician and soldier who represented Tennessee's 2nd district in the United States House of Representatives from 1819 to 1827. He also served several terms in the Tennes ...

. Jackson and Cocke were not ready to move until early October.

In addition to the state actions, U.S. Indian agent Hawkins organized the friendly Lower Creek under Major William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth cen ...

, an Indian chief, to aid the Georgia and Tennessee militias in actions against the Red Sticks. At the request of Chief Federal Agent Return J. Meigs (called "White Eagle" by the Indians for the color of his hair), the Cherokee Nation voted to join the Americans in their fight against the Red Sticks. Under the command of Chief Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge (and sometimes Pathkiller II) (c. 1771 – 22 June 1839) (also known as ''Nunnehidihi'', and later ''Ganundalegi'') was a Cherokee leader, a member of the tribal council, and a lawmaker. As a warrior, he fought in the ...

, 200 Cherokee fought with the Tennessee Militia under Colonel Andrew Jackson.

At most, the Red Stick force consisted of 4,000 warriors, possessing perhaps 1,000 muskets. They had never been involved in a large-scale war, not even against neighboring American Indians. Early in the war, General Cocke observed that arrows "form a very principal part of the enemy's arms for warfare, every man having a bow with a bundle of arrows, which is used after the first fire with the gun until a leisure time for loading offers". Many Creek tried to remain friendly to the United States, but, after Fort Mims, few European Americans in the region distinguished between friendly and unfriendly Creeks.

The Holy Ground (Econochaca), located near the junction of the Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and Coosa Rivers, was the heart of the Red Stick Confederation. It was about 150 miles (240 km) from the nearest supply point available to any of the three American armies. The easiest attack route was from Georgia through the line of forts on the frontier and then along a good road that led to the Upper Creek towns near the Holy Ground, including nearby Hickory Ground. Another route was north from Mobile along the Alabama River. Jackson's route of advance was south from Tennessee through a mountainous and pathless terrain.

Georgia campaign

By August, the Georgia Volunteer Army and state militia had been mobilized in anticipation of war with the Creeks. The news of Fort Mims first reached Georgia on September 16, and was taken as legal grounds to begin a military offensive. In addition, Benjamin Hawkins wrote to Brigadier General John Floyd on September 30 that the Red Stick war party had "received 25 small guns" at Pensacola. The immediate concern of the force was the defense of Georgia's "Indian Line

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by George III of the United Kingdom, King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred New France, French territory ...

", separating Indian territory from U.S. territory at the Ocmulgee River

The Ocmulgee River () is a western tributary of the Altamaha River, approximately 255 mi (410 km) long, in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the westernmost major tributary of the Altamaha.

.

The proximity of Jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases,Kostov, R. I. 2010. Review on the mineralogical systematics of jasper and related rocks. – Archaeometry Workshop, 7, 3, 209-213PDF/ref> ...

and Jones

Jones may refer to:

People

*Jones (surname), a common Welsh and English surname

*List of people with surname Jones

* Jones (singer), a British singer-songwriter

Arts and entertainment

* Jones (''Animal Farm''), a human character in George Orwell ...

counties to hostile Creek towns resulted in a regiment of Georgia volunteer militia under Major General David Adams. John Floyd was made general of the main Georgia army (in September 1812 and numbering 2,362 men). The Georgia Army was aided by Cherokee and independent Creek allies, as well as a number of Georgia volunteer militia. Floyd's task was to advance to the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers and join the Army of Tennessee.

Due to the state's failure to secure supplies early enough in the year, Floyd gained a few months to train and drill the men at Fort Hawkins. On November 24, General Floyd crossed the Chattahoochee

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the con ...

and established Fort Mitchell, where he was joined by 300-400 Creek from Coweta

Coweta is a city in Wagoner County, Oklahoma, United States, a suburb of Tulsa. As of 2010, its population was 9,943. Part of the Creek Nation in Indian Territory before Oklahoma became a U.S. state, the town was first settled in 1840.Autossee on the Tallapoosa River, a Red Stick stronghold only 20 miles from the Coosa River. On November 29, he attacked Autossee. Floyd's losses were 11 killed and 54 wounded. Floyd estimated that 200 Creek were killed. Having achieved the destruction of the town, Floyd returned to Fort Mitchell.

The second westward advance of Floyd's troops departed Fort Mitchell with a force of 1,100 militia and 400 friendly Creek. Along the way they fortified

After Talladega, however, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments.

After Talladega, however, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments.

On August 9, 1814,

On August 9, 1814,

The Creek War, 1813-1814.

' Washington, D.C.:

"The Creek War 1813-1814"

Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, National Park Service {{DEFAULTSORT:Creek War 1810s in the United States Andrew Jackson Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America History of Georgia (U.S. state) Muscogee Pre-statehood history of Alabama War of 1812 Wars between the United States and Native Americans

Fort Bainbridge

Fort Bainbridge was an earthen fort located along the Federal Road on what is today the county line between Macon and Russell counties in Alabama. Fort Bainbridge was located twenty-five miles west of Fort Mitchell.

History Creek War

Fort Bai ...

and Fort Hull

Fort Hull was an earthen fort built in present-day Macon County, Alabama in 1814 during the Creek War. After the start of hostilities, the United States decided to mount an attack on Creek territory from three directions. The column advancing wes ...

on the Federal Road. On January 26, 1813, they set up a camp on the Callabee Creek near the abandoned site of Autossee. Red Stick chiefs William Weatherford

William Weatherford, also known after his death as Red Eagle (ca. 1765 – March 24, 1824), was a Creek chief of the Upper Creek towns who led many of the Red Sticks actions in the Creek War (1813–1814) against Lower Creek towns and against ...

, Paddy Walsh (creek indian), High-head Jim, and William McGillivray raised a combined force of at least 1,300 warriors to stop the advance. This was the largest combined force raised by the Creek during the entire war. On January 29, the Red Sticks launched an attack on the American camp at dawn. After daylight, Floyd's army repulsed the attack. Casualty figures vary for Floyd's force, from 17 to 22 killed, and 132 to 147 wounded. Floyd estimated Red Stick casualties as 37 killed, including Chief High-head Jim. Georgia retreated to Fort Mitchell with Floyd, who was severely wounded in the leg. The Battle of Calebee Creek

The Battle of Calebee Creek (also spelled ''Calabee'', ''Callabee'', or in the official report at the time, "Chalibee") took place on January 27, 1814, during the Creek War, in Macon County, Alabama, west of Fort Mitchell. General Floyd, wit ...

was Georgia's last offensive operation of the war.

Mississippi militia

In October, General Thomas Flourney organized a force of about 1,000—consisting of the Third United States Infantry, militia, volunteers, andChoctaw Indians

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

—at Fort Stoddert

Fort Stoddert, also known as Fort Stoddard, was a stockade fort in the U.S. Mississippi Territory, in what is today Alabama. It was located on a bluff of the Mobile River, near modern Mount Vernon, close to the confluence of the Tombigbee and Al ...

. General Claiborne, ordered to lay waste to Creek property near the junction of the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers, advanced from Fort St. Stephen. He achieved some destruction but no military engagement. At roughly the same time, Captain Samuel Dale

Samuel Dale (1772 – ), known as the "Daniel Boone of Alabama", was an American frontiersman, trader, miller, hunter, scout, courier, soldier, spy, army officer, and politician, who fought under General Andrew Jackson, in the Creek War, la ...

left Fort Madison (near Suggsville) going southward to the Alabama River. On November 12 a small party rowed out to intercept a war canoe. Dale wound up alone in the canoe in hand-to-hand combat with four warriors, an encounter which became known as the Canoe Fight

The Canoe Fight was a skirmish between Mississippi Territory militiamen led by Captain Samuel Dale and Red Stick warriors that took place on November 12, 1813 as part of the Creek War. The skirmish was fought largely from canoes and was a vic ...

.

Continuing to a point about 85 miles (140 km) north of Fort Stoddert, Claiborne established Fort Claiborne. On December 23, he encountered a small force at the Holy Ground and burned 260 houses. William Weatherford

William Weatherford, also known after his death as Red Eagle (ca. 1765 – March 24, 1824), was a Creek chief of the Upper Creek towns who led many of the Red Sticks actions in the Creek War (1813–1814) against Lower Creek towns and against ...

was nearly captured during this engagement. Casualties for the Mississippians were 1 killed and 6 wounded. 30 Creek soldiers were killed in the engagement, however. Because of supply shortages, Claiborne withdrew to Fort St. Stephens.

North Carolina and South Carolina militia

Brigadier General Joseph Graham's brigade of troops from North and South Carolina, including Colonel Reuben Nash's South Carolina militia, deployed along the Georgia frontier to deal with the Red Sticks. Colonel Nash's South Carolina regiment of volunteer militia traveled from South Carolina at the end of January 1814. The militia marched to the start of the Federal Road inAugusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

, walking to Fort Benjamin Hawkins

Fort Hawkins was a fort built between 1806 and 1810 in the historic Creek Nation by the United States government under President Thomas Jefferson and used until 1824. Built in what is now Georgia at the Fall Line on the east side of the Ocmulgee Ri ...

(in modern Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Situated near the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is located southeast of Atlanta and lies near the geographic center of the state of Geo ...

) en route to reinforce the various forts including Fort Mitchell (in modern Phenix City, Alabama). Other companies in the Nash's regiment were at Fort Mitchell by July 1814. Graham's brigade participated in only a few skirmishes before returning home.

Tennessee campaign

Although Jackson's mission was to defeat the Creek, his larger objective was to move onPensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. Jackson's plan was to move south, build roads, destroy Upper Creek towns, and then later proceed to Mobile to stage an attack on Spanish-held Pensacola. He had two problems: logistics and short enlistments. When Jackson began his advance, the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

was low, making it difficult to move supplies, and there was little forage for his horses.

On October 10, Jackson, along with 2,500 troops, set out on the expedition, his arm in a sling. Jackson established Fort Strother

Fort Strother was a stockade fort at Ten Islands in the Mississippi Territory, in what is today St. Clair County, Alabama. It was located on a bluff of the Coosa River, near the modern Neely Henry Dam in Ragland, Alabama. The fort was built by G ...

as a supply base. On November 3, his top cavalry officer, Brigadier General John Coffee

John R. Coffee (June 2, 1772 – July 7, 1833) was an American planter of Irish descent, and state militia brigadier general in Tennessee. He commanded troops under General Andrew Jackson during the Creek Wars (1813–14) and during the Battle ...

, defeated a band of Red Sticks at the Battle of Tallushatchee

The Battle of Tallushatchee was a battle fought during the War of 1812 and Creek War on November 3, 1813, in Alabama between Native American Red Stick Creeks and United States dragoons. A cavalry force commanded by Brigadier General John Coffee ...

. It was a brutal battle, and many Red Sticks, including some women and children, were killed. After this, Jackson received a call for help from 150 allied Creeks besieged by 700 Red Stick warriors. Jackson marched his troops to relieve the siege, and won another decisive victory at the Battle of Talladega

The Battle of Talladega was fought between the Tennessee Militia and the Red Stick Creek Indians during the Creek War, in the vicinity of the present-day county and city of Talladega, Alabama, in the United States.

Background

When General J ...

on November 9.

After Talladega, however, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments.

After Talladega, however, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments. John Alexander Cocke

John Alexander Cocke (December 28, 1772February 16, 1854) was an American politician and soldier who represented Tennessee's 2nd district in the United States House of Representatives from 1819 to 1827. He also served several terms in the Tennes ...

, with the East Tennessee Militia, took the field on October 12. His route of march was from Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state's ...

to Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

and then along the Coosa River toward Fort Strother

Fort Strother was a stockade fort at Ten Islands in the Mississippi Territory, in what is today St. Clair County, Alabama. It was located on a bluff of the Coosa River, near the modern Neely Henry Dam in Ragland, Alabama. The fort was built by G ...

. Because of rivalry between the East and West Tennessee militias, Cocke was in no hurry to join Jackson, particularly after he angered Jackson by mistakenly attacking a friendly village on November 17. When he finally reached Fort Strother on December 12, the East Tennessee men only had 10 days remaining on their enlistments. Jackson had no choice but to dismiss them. Furthermore, General Coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulant, stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

S ...

, who had returned to Tennessee for remounts, wrote Jackson that the cavalry had deserted. By the end of 1813, Jackson was down to a single regiment whose enlistments were due to expire in mid-January.

Although Governor Blount had ordered a new levee of 2,500 troops, Jackson would not be up to full strength until the end of February. When a draft of 900 raw recruits arrived unexpectedly on January 14, Jackson was down to a cadre of 103 and Coffee, who had been "abandoned by his men".

Since new men had enlistment contracts of only sixty days, Jackson decided to get the most out of his untried force. He departed Fort Strother on January 17 and marched toward the village of Emuckfaw to cooperate with the Georgia Militia. However, this was a risky decision. It was a long march through difficult terrain against a numerically superior force, the men were inexperienced, undisciplined, and insubordinate, and a defeat would have prolonged the war. After two indecisive battles at Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek, Jackson returned to Fort Strother and did not resume the offensive until mid-March.

The arrival of the 39th United States Infantry on February 6, 1814, provided Jackson a disciplined core for his force, which ultimately grew to about 5,000 men. After Governor Blount ordered the second draft of Tennessee militia, Cocke, with a force of 2,000 six-month men, once again marched from Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state's ...

to Fort Strother. Cocke's men mutinied when they learned that Jackson's men only had three-month enlistments. Cocke tried to pacify his men, but Jackson misunderstood the situation and ordered Cocke's arrest as an instigator. The East Tennessee militia reported to Fort Strother without further comment on their term of service. Cocke was later cleared.

Jackson spent the next month building roads and training his force. In mid-March, he moved against the Red Stick force concentrated on the Tallapoosa at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend). He first moved south along the Coosa, about half the distance to the Creek position, and established a new outpost at Fort Williams. Leaving another garrison there, he then moved on Tohopeka with a force of about 3,000 effective fighting men augmented by 600 Cherokee and Lower Creek allies. The Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which occurred on March 27, was a decisive victory for Jackson, effectively ending the Red Stick resistance.

Results

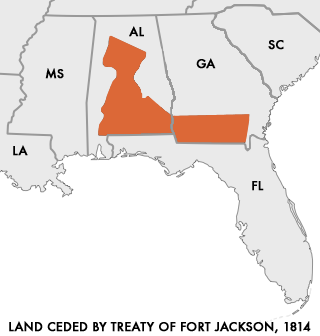

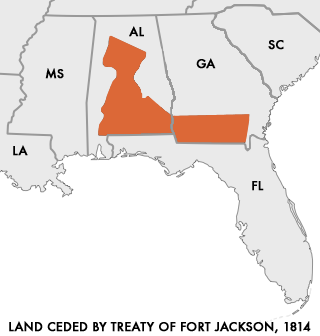

On August 9, 1814,

On August 9, 1814, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

forced headmen of both the Upper and Lower towns of Creek to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

. Despite protest of the Creek chiefs who had fought alongside Jackson, the Creek Nation ceded 21,086,793 acres (85,335 km²) of land—approximately half of present-day Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and part of southern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

—to the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

. Even though the Creek War was largely a civil war among the Creek, Andrew Jackson recognized no difference between his Lower Creek allies and the Red Sticks who fought against him. He took the lands of both for what he considered the security needs of the United States. Jackson forced the Creek to cede 1.9 million acres (7,700 km²) that was also claimed as hunting grounds of the Cherokee Nation, who had fought as U.S. allies during the Creek War as well.

With the Red Sticks subdued, Jackson turned his focus on the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

region in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. On his own initiative, he invaded Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

and drove a British force out of Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

.Mahon, p. 350 He defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French ...

on January 8, 1815. In 1818, Jackson again invaded Florida, where some of the Red Stick leaders had fled, an event known as the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

.

As a result of these victories, Jackson became a national figure and eventually was elected the seventh President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

in 1829. As president, Andrew Jackson advocated the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

, passed by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

in 1830, which authorized negotiation of treaties for exchange of land and payment of annuities, and authorized forceful removal of the Southeastern tribes

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

to prescribed Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, an ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

now known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

.

See also

*Indian Campaign Medal

The Indian Campaign Medal is a decoration established by War Department General Orders 12, 1907.

*List of Indian massacres

In the history of the European colonization of the Americas, an Indian massacre is any incident between European settlers and indigenous peoples wherein one group killed a significant number of the other group outside the confines of mutual c ...

* George Mayfield, interpreter and spy for Andrew Jackson, later honored by the Creek for his integrity during treaty negotiations

References

Sources

* * Adams, Henry, ''History of the United States of America During the Administrations of James Madison'' (1889) *Andrew Burstein

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derived ...

''The Passions of Andrew Jackson'' (Alfred A. Kopf 2003), p. 106

* Holland, James W. "Andrew Jackson and the Creek War: Victory at the Horseshoe Bend", ''Alabama Review

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

'', 1968 21(4): 243–275.

* Kanon, Thomas. "'A Slow, Laborious Slaughter': The Battle Of Horseshoe Bend." ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly'', 1999 58(1): 2–15.

* useful for illustrations

* Mahon, John K., ''The War of 1812'', (University of Florida Press 1972)

*

*

* Waselkov, Gregory A. ''A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813–1814.'' Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

*

Further reading

* Richard D. Blackmon.The Creek War, 1813-1814.

' Washington, D.C.:

Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

, United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

, 2014.

* Mike Bunn and Clay Williams. ''Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812''. The History Press, 2008.

* Kathryn E. Holland Braund. ''Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815''. University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

* Benjamin W. Griffith Jr. ''McIntosh and Weatherford: Creek Indian Leaders''. University of Alabama Press, 1998.

* Angela Pulley Hudson. ''Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South''. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

* Roger L. Nichols. ''Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples.'' Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

* Frank L. Owsley Jr. ''Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812–1815''. University of Alabama Press, 2000.

* Claudio Saunt. ''A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816''. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

* Gregory A. Waselkov. ''A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813–1814''. University of Alabama Press, 2006.

* J. Leitch Wright Jr. ''Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People''. University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

External links

"The Creek War 1813-1814"

Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, National Park Service {{DEFAULTSORT:Creek War 1810s in the United States Andrew Jackson Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America History of Georgia (U.S. state) Muscogee Pre-statehood history of Alabama War of 1812 Wars between the United States and Native Americans