The Rashidieh camp is the second most populous

Palestinian refugee camp

Camps are set up by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to accommodate Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA, who fled or were expelled during the 1948 Palestinian e ...

in

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

, located on the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

coast about five kilometres south of the city of

Tyre (Sur).

Name

The name has also been transliterated into Rashidiya, Rashidiyah, Rachidiye, Rashidiyyeh, Rashadiya, Rashidiyya, Reshîdîyeh'','' or Rusheidiyeh with or without a version of the article Al, El, Ar, or Er.

The

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

-based

Palestine Exploration Fund

The Palestine Exploration Fund is a British society based in London. It was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the stud ...

(PEF) and other sources recorded that in the Mid-19th century the settlement was named after its then owner, the

Ottoman top-

diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or interna ...

and

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, ...

Mustafa Reşid Pasha

Koca Mustafa Reşid Pasha (literally ''Mustafa Reşid Pasha the Great''; 13 March 1800 – 7 January 1858) was an Ottoman statesman and diplomat, known best as the chief architect behind the Ottoman government reforms known as Tanzimat.

Born i ...

, known best as the chief architect behind the

regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

's modernization

reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

s known as

Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

.

Territory

There is an abundance of

fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does incl ...

supplies in the area with the

springs of Rashidieh itself and those of

Ras al-Ain nearby.

To its northern side, Rashidieh borders the

Tyre Coast Nature Reserve

Tyre Coast Nature Reserve to the southeast of Tyre, Lebanon covers over and is divided into three zones: the tourism zone (public beaches, the old city and Souks, the ancient port), the agricultural and archaeological zone, and the Conservation ...

.

According to a 1998 fact-finding mission of the

Danish Immigration Service The Danish Immigration Service ( da, Udlændingestyrelsen or ''Udlændingeservice'') is a directorate within the Danish Ministry of Refugees, Immigration and Integration Affairs.

The service administrates the Danish Aliens Act ( da, Udlændingel ...

, the camp covers an area of 248,426

square meters

The square metre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures) or square meter ( American spelling) is the unit of area in the International System of Units (SI) with symbol m2. It is the area of a square ...

. Journalist

Robert Fisk

Robert Fisk (12 July 194630 October 2020) was a writer and journalist who held British and Irish citizenship. He was critical of United States foreign policy in the Middle East, and the Israeli government's treatment of Palestinians. His stan ...

estimated the size to be four square miles.

A 2017

census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses inc ...

found that there were 1,510 buildings with 2,417

household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is i ...

s in Rashidieh.

History of the site

Prehistoric times

According to

Ali Badawi, the long-time chief-

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

for Southern Lebanon at the Directorate-General of Antiquities, it can be generally assumed that all villages around Tyre were established already during

prehistoric times

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

of the

neolithic age

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

(5.000 BCE), especially in the fertile area of Ras al-Ain, next to the Tell El-Rashdiyeh (the Hill of Rashidieh).

Ancient times

Phoenician times

Many scholars assume that the area of what is now Rashidieh actually used to be the original

Ushu

Ushu (in the Amarna Letters Usu) was an ancient mainland city that supplied the city of Tyre with water, supplies and burial grounds. Its name was based upon the mythical figure Usoos or Ousoüs, a descendant of Genos and Genea whose children alle ...

(also transliterated Usu or Uzu), founded on the

mainland

Mainland is defined as "relating to or forming the main part of a country or continent, not including the islands around it egardless of status under territorial jurisdiction by an entity" The term is often politically, economically and/or dem ...

around 2750 BCE as a walled place.

It was later called Palaetyrus (also spelled Palaityros or Palaeotyre), meaning "Old Tyre" in

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, and was the lifeline for Island Tyre as its continental twin sister:

"''To an overpopulated island, its mainland territory was a vital necessity, supplying it with agricultural products, drinking water, wood and murex

''Murex'' is a genus of medium to large sized predatory tropical sea snails. These are carnivorous marine gastropod molluscs in the family Muricidae, commonly called "murexes" or "rock snails".Houart, R.; Gofas, S. (2010). Murex Linnaeus, 175 ...

. In isolation the island city was nothing.''"

One of the reasons to locate Ushu/Palaetyrus in the Rashidieh area is the delineation of its

acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

by Ancient-Greek

geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

, who visited Tyre himself.

The springs of Ras al-Ain were described by later scholars as the "

cistern

A cistern (Middle English ', from Latin ', from ', "box", from Greek ', "basket") is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater. Cisterns are distinguished from wells by ...

s of

Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

" and said to have been commissioned by the legendary

King of Israel

This article is an overview of the kings of the United Kingdom of Israel as well as those of its successor states and classical period kingdoms ruled by the Hasmonean dynasty and Herodian dynasty.

Kings of Ancient Israel and Judah

The Hebr ...

, who was a close ally of Tyrian king

Hiram I.

Very few

archaeological excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

have been conducted in Rashidieh. However, the collections of the

National Museum of Beirut

The National Museum of Beirut ( ar, متحف بيروت الوطنيّ, ''Matḥaf Bayrūt al-waṭanī'' or French: Musée national de Beyrouth) is the principal museum of archaeology in Lebanon. The collection begun after World War I, and the m ...

hold a number of items which were found there. Amongst them is an

amphora

An amphora (; grc, ἀμφορεύς, ''amphoreús''; English plural: amphorae or amphoras) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storag ...

with

Phoenician inscriptions dated to the

Iron Age II

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

and a

cinerary urn dated 775-750 BCE. The latter was an import from

Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

and gives evidence that Rashidieh was used as a

necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

as well.

However, Ushu/Palaetyrus apparently suffered great damages when the

Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

king

Shalmaneser V

Shalmaneser V ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Tiglath-Pileser III in 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalman ...

besieged the twin-city in the 720s BCE. Likewise during the attack by

Neo-Babylonian

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and be ...

king

Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

, who started a siege of Tyre in 586 BCE that went on for thirteen years.

Hellenistic times

Reportedly, when

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

arrived at the gates of Tyre in 332 BCE and proposed to sacrifice to city

deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

Melqart

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre and a major deity in the Phoenician and Punic pantheons. Often titled the "Lord of Tyre" (''Ba‘al Ṣūr''), he was also known as the Son of ...

in the temple on the island, the Tyrian government refused this and instead suggested that Alexander sacrifice at another temple on the mainland at Old Tyre. Angered by this rejection and the city's loyalty to

Persian king

Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, Alexander started his

Siege of Tyre despite its reputation as being impregnable. However, the

Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may specifically refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North Ma ...

conqueror succeeded after seven months by demolishing the old city on the mainland and using its stones to construct a

causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Tr ...

to the island. This

isthmus

An isthmus (; ; ) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea counterpart of an isthmus ...

increased greatly in width over the centuries because of extensive

silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

depositions on either side, making the former island a permanent

peninsula

A peninsula (; ) is a landform that extends from a mainland and is surrounded by water on most, but not all of its borders. A peninsula is also sometimes defined as a piece of land bordered by water on three of its sides. Peninsulas exist on a ...

- based on the ruins and rubble of Palaetyrus.

Roman times (64BCE-395)

During

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

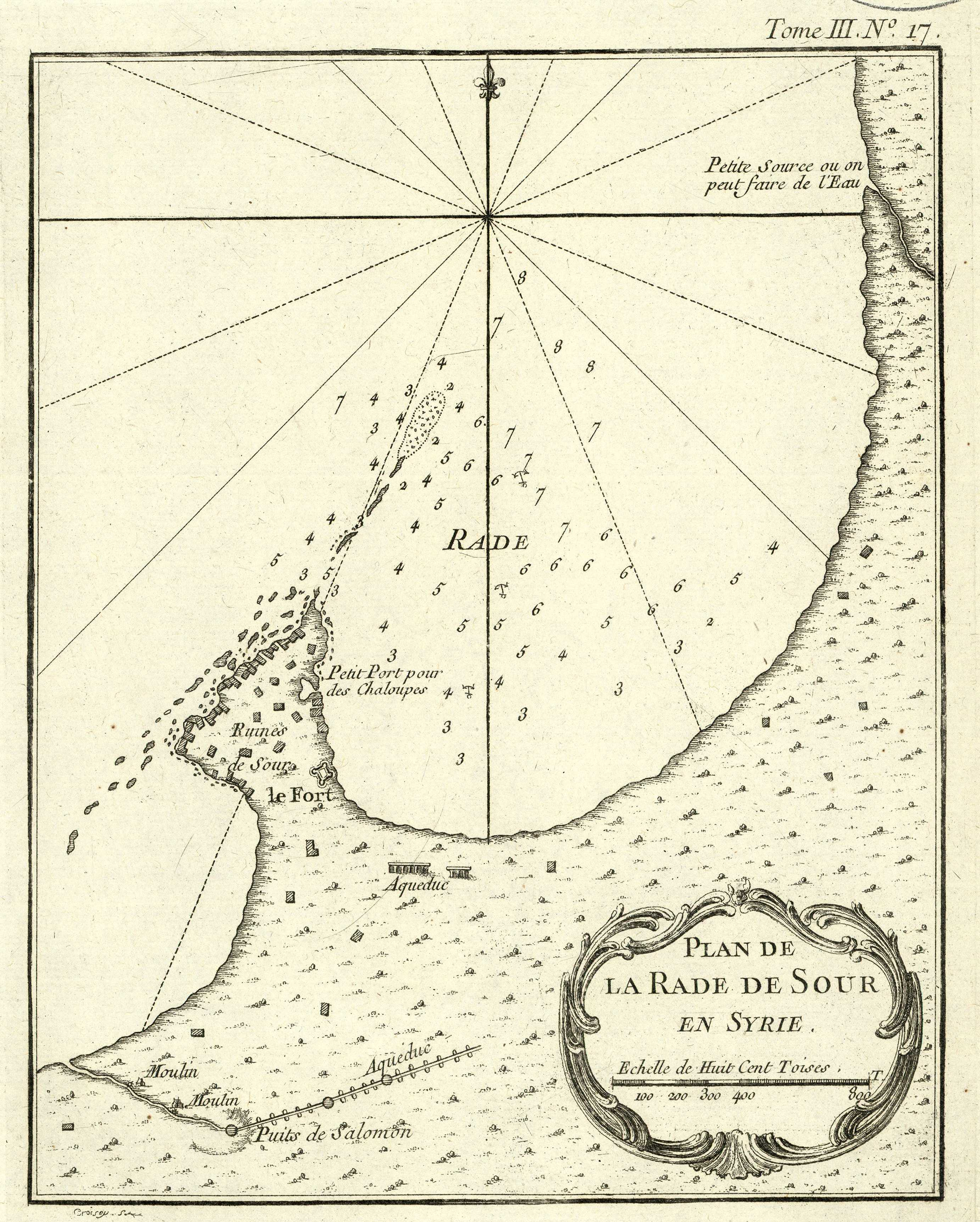

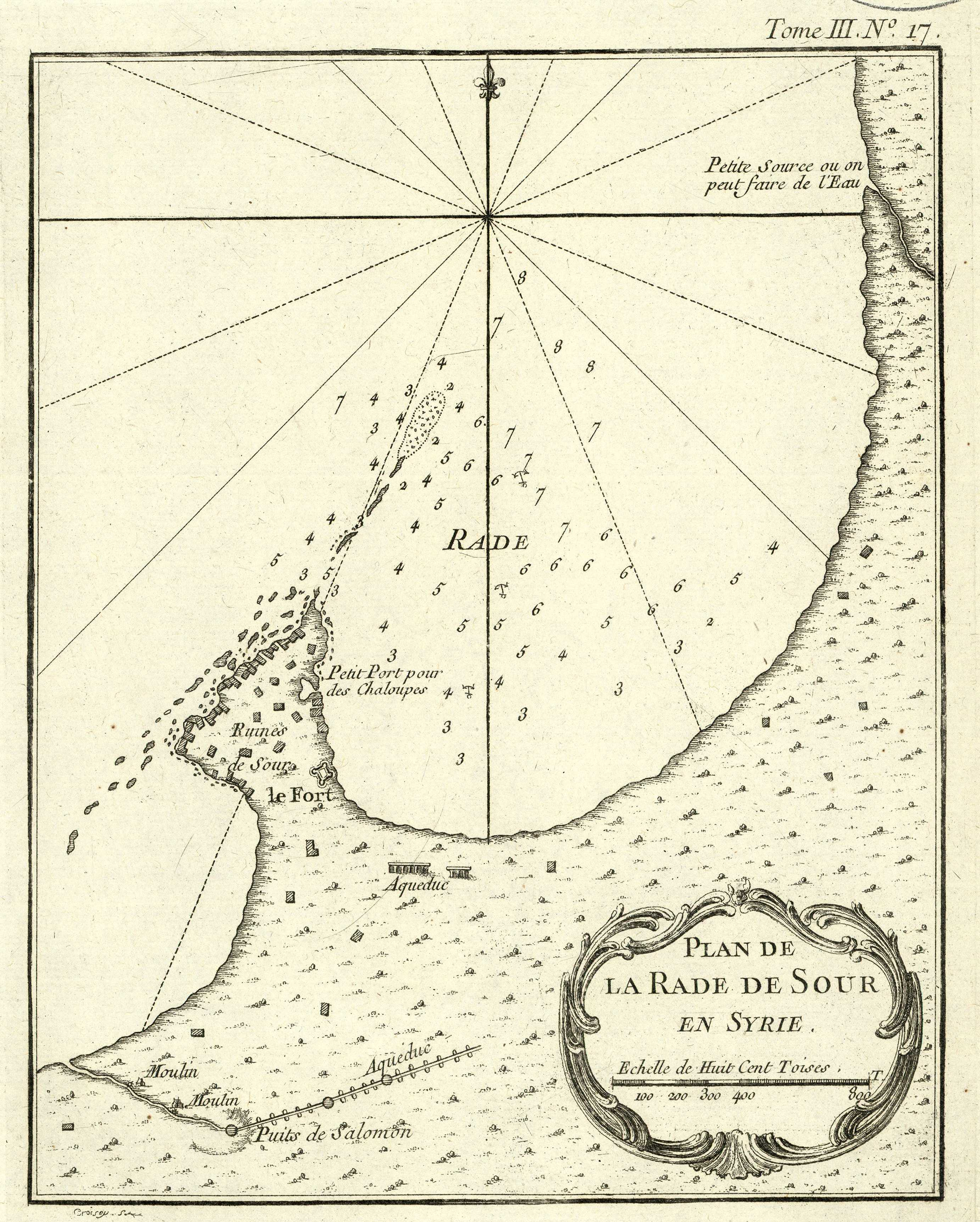

times, large water reservoirs were built in Ras al-Ain as well as an

aqueduct which channeled the water to Tyre.

At the same time, the use of the area as a burial ground seems to have continued: a

marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

from the first or second century CE was discovered there in 1940. It is exhibited at the National Museum in Beirut.

Byzantine period (395–640)

According to the Syrian scholar

Evagrius Scholasticus

Evagrius Scholasticus ( el, Εὐάγριος Σχολαστικός) was a Syrian scholar and intellectual living in the 6th century AD, and an aide to the patriarch Gregory of Antioch. His surviving work, ''Ecclesiastical History'' (), compris ...

(536-596 CE), the hill of what is now Rashidieh was known as ''Sinde -'' "''a place where a

hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a C ...

called Zozyma used to dwell.''"

Over the course of the 6th century CE, starting in 502, a series of earthquakes shattered Tyre area and left the city diminished. The worst one was the

551 Beirut earthquake

The 551 Beirut earthquake occurred on 9 July with an estimated magnitude of about 7.5 on the moment magnitude scale and a maximum felt intensity of X (''Extreme'') on the Mercalli intensity scale. It triggered a devastating tsunami which affected ...

. It was accompanied by a

Tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

and probably destroyed also much of what was left in the area of what is now Rashidieh. In addition, the city and its population increasingly suffered during the 6th century from the political chaos that ensued when the Byzantine empire was torn apart by wars. The city remained under Byzantine control until it was captured by the Sassanian shah

Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

at the turn from the 6th to the 7th century CE, and then briefly regained until the

Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

, when in 640 it was taken by the

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

forces of the

Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate ( ar, اَلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his ...

.

Medieval times

Early Muslim period (640–1124)

As the bearers of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

restored peace and order, Tyre soon prospered again and continued to do so during half a millennium of

Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

rule.

The Rashidun period only lasted until 661. It was followed by the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

(until 750) and the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

. In the course of the centuries, Islam spread and

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

became the language of administration instead of Greek.

At the end of the 11th century, Tyre avoided being attacked by paying tribute to the

Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

who marched on Jerusalem. However, in late 1111,

King Baldwin I of Jerusalem laid siege on the former island city and probably occupied the mainland, including the area that is now Rashidieh, for that purpose. Tyre in response put itself under the protection of the Seljuk military leader

Toghtekin

Toghtekin or Tughtekin (Modern tr, Tuğtekin; Arabicised epithet: ''Zahir ad-Din Tughtikin''; died February 12, 1128), also spelled Tughtegin, was a Turkic military leader, who was ''atabeg'' of Damascus from 1104 to 1128. He was the founder o ...

. Supported by

Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

forces, he intervened and forced the Franks to raise the siege in April 1112, after about 2.000 of Baldwin's troops had been killed. A decade later, the Fatimids sold Tyre to Toghtekin who installed a garrison there.

Crusader period (1124–1291)

On 7 July 1124, in the aftermath of the

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

, Tyre was the last city to be eventually conquered by the Christian warriors, a

Frankish army on the coast - i.e. also in today's Rashidieh area - and a fleet of the

Venetian Crusade from the sea side. The takeover followed a siege of five and a half months that caused great suffering from hunger to the population.

Eventually, Tyre's Seljuk ruler Toghtekin negotiated an agreement for surrender with the authorities of the Latin

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

.

Under its new rulers, Tyre and its countryside - including what is now Rashidieh - were divided into three parts in accordance with the ''

Pactum Warmundi

The Pactum Warmundi was a treaty of alliance established in 1123 between the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Republic of Venice.

Background

In 1123, King Baldwin II was taken prisoner by the Artuqids, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem was sub ...

'': two-thirds to the royal domain of Baldwin and one third as autonomous trading colonies for the Italian merchant cities of Genoa, Pisa and - mainly to the

Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

. He had a particular interest in supplying silica sands to the glassmakers of

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and so it may be assumed that the area of what is now Rashidieh fell into his interest sphere.

Mamluk period (1291–1516)

In 1291, Tyre was again taken, this time by the Mamluk Sultanate's army of

Al-Ashraf Khalil

Al-Ashraf Salāh ad-Dīn Khalil ibn Qalawūn ( ar, الملك الأشرف صلاح الدين خليل بن قلاوون; c. 1260s – 14 December 1293) was the eighth Bahri Mamluk sultan, succeeding his father Qalawun. He served from 12 Novem ...

. He had all fortifications demolished to prevent the Franks from re-entrenching. After Khalil's death in 1293 and political instability, Tyre lost its importance and "''sank into obsurity.''" When the

Moroccan explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

Ibn Batutah visited Tyre in 1355, he found it a mass of ruins.

Modern times

Ottoman rule (1516-1918)

The Ottoman Empire conquered the Levant in 1516, yet the desolate area of Tyre remained untouched for another ninety years until the beginning of the 17th century, when the leadership at the

Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

appointed the

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

leader

Fakhreddine II as

Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

to administer

Jabal Amel

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

(modern-day

South Lebanon

Southern Lebanon () is the area of Lebanon comprising the South Governorate and the Nabatiye Governorate. The two entities were divided from the same province in the early 1990s. The Rashaya and Western Beqaa Districts, the southernmost distric ...

).

He encouraged the systematically discriminated

Shiites - known as the

Metwalis - to settle near Tyre in order to secure the road to

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, and thus laid the foundation of Rashidieh's 19th century

demographics

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

.

However, the development of the Greater Tyre area stalled once again in 1635, when

Sultan Murad IV had Fakhreddine executed for his political ambitions. Henceforth, it is unclear how the area of Rashidieh developed in the following 200 years, except that it was apparently called ''Tell Habish'' (also spelled ''Habesh'') during that time, the "Hill of Habish":

"Habish" may be translated as "

Ethiopian

Ethiopians are the native inhabitants of Ethiopia, as well as the global diaspora of Ethiopia. Ethiopians constitute several component ethnic groups, many of which are closely related to ethnic groups in neighboring Eritrea and other parts of ...

", which in turn might refer to the Tyrian brothers

Frumentius and Edesius, who got shipwrecked on the

Eritrean coast in the 4th century CE. While Frumentius has been credited with bringing

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

to the

Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in w ...

and became the first bishop of the

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

, Edesius returned to Tyre to become a priest.

It was then in 1856, according to some sources, that

Mustafa Reşid Pasha

Koca Mustafa Reşid Pasha (literally ''Mustafa Reşid Pasha the Great''; 13 March 1800 – 7 January 1858) was an Ottoman statesman and diplomat, known best as the chief architect behind the Ottoman government reforms known as Tanzimat.

Born i ...

- the chief architect behind the Ottoman government reforms known as

Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

- obtained personal ownership of the lands in the area of Tell Habish.

This was perhaps when he became

Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

for the fifth time in his career at the end of that year. In any case, the transfer took obiously only place after the Ottoman leadership in

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

regained control over Jabal Amel from

Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1839 after almost eight years. The army of the rebellious

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

ian Governor was defeated not only with allied support from the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, but mainly by Shiite forces under the leadership of the

Ali al-Saghir dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

.

The PEF

''Survey of Western Palestine'' (SWP) - led by

Herbert Kitchener at the beginning of his military career - explored the area in May 1878 and described ''Er Rusheidiyeh'' as follows:

"''It is a hill about sixty feet above the level of the sea. It took its present name a few years ago, Rusheid Pasha (commonly written Reshid Pasha) having acquired the place and built a farm upon it of the old materials which covered the soil."''

And:

"''A large square building, built by Rusheid Pasha for a factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. ...

; now contains about 70 Metawileh, and is surrounded by gardens of olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ' ...

s, figs, pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

s, and lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

s. It stands on a slight hill above the plain, and has two strong springs near, surrounded by masonry

Masonry is the building of structures from individual units, which are often laid in and bound together by mortar; the term ''masonry'' can also refer to the units themselves. The common materials of masonry construction are bricks, building ...

.''"

According to the

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

n historian and politician

Johann Nepomuk Sepp

Johann Nepomuk Sepp (7 August 1816 – 5 June 1909) was a German historian and politician, and a native of Bavaria.

Life

Johann Nepomuk Sepp was born in Bad Tölz, Bavaria, to a tanner and dyer, Josef Bernhard Sepp and his wife Maria Victoria ...

, who in 1874 led an

Imperial German mission to Tyre in search of the bones of

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I "Barbarossa", the estate was taken over after the death of

Reşid Pasha in 1858 by

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

Abdulaziz

Abdulaziz ( ota, عبد العزيز, ʿAbdü'l-ʿAzîz; tr, Abdülaziz; 8 February 18304 June 1876) was the 32nd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and reigned from 25 June 1861 to 30 May 1876, when he was overthrown in a government coup. He was a ...

.

In 1903, the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

archaeologist

Theodore Makridi

Theodore Makridi Bey (1872–1940) was an Ottoman and Turkish - Greek archaeologist who conducted the first excavations of the Hittite capital, Hattusas

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas ; Hittite: URU''Ḫa-at-tu-ša'', Turkish: Hattuşa� ...

Bey, curator of the

Imperial Museum at Constantinople conducted archaeological excavations in Rashidieh and discovered a number of cinerary urns with human bones and ashes. Some were locally made while others were imported from Cyprus.

These findings were apparently sent to the Ottoman capital.

A map from a 1906

Baedeker

Verlag Karl Baedeker, founded by Karl Baedeker on July 1, 1827, is a German publisher and pioneer in the business of worldwide travel guides. The guides, often referred to simply as " Baedekers" (a term sometimes used to refer to similar works fro ...

travel guide designates the area as "''Tell Habesh or Reshîdîyeh''". It showed gardens, a mill and a Khan (a

Caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was a roadside inn where travelers ( caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes covering ...

).

French Mandate colonial rule (1920–1943)

On the first of September 1920, the colonial French rulers proclaimed the new State of

Greater Lebanon

The State of Greater Lebanon ( ar, دولة لبنان الكبير, Dawlat Lubnān al-Kabīr; french: État du Grand Liban), informally known as French Lebanon, was a state declared on 1 September 1920, which became the Lebanese Republic ( ar, ...

. According to an

oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

project, the new authorities gave "''sections of Rashidieh Hill, where there were already two churches''", to the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

’s

Waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitab ...

, i.e. its

financial endowment

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to the will of its founders and donors. Endowments are o ...

.

It is unclear though whether this was the Latin-Catholic School or one of its

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

like the

Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

in Tyre, or the

Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre

Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre (in Latin: Archeparchia Tyrensis Maronitarum) is an Archeparchy of the Maronite Church immediately subject to the Maronite Patriarch of Antioch. In 2014 there were 42,500 baptized. It is currently ruled by Arch ...

, or the

Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre

Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre (Latin: Archeparchy Tyrensis Graecorum Melkitarum) is a metropolitan see of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. In 2009 there were 3,100 baptized. It is currently governed by an Apostolic Administrator, Ar ...

. The latter has apparently the largest property holdings of the Christian confessions in the area and is commonly just called "the Catholic church". In any event, it has been reported that a Lebanese Christian village developed in Rashidieh.

In the following years, survivors of the

Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

started arriving in Tyre,

mostly by boat:

"''The first agricultural settlement was created in Ra's al-'Ain, near the city of Tyre, in 1926. The operation quickly failed due to the animosity between refugees from different regions, but also between the refugees and the local population. The refugees had therefore to be relocated to Beirut.''"

Yet more refugees arrived and hence a branch of the

Armenian General Benevolent Union was founded in Tyre in 1928.

Then, in 1936, the colonial authorities started constructing a camp for

Armenian refugees in Rashidieh.

According to the above-mentioned oral history project, they were settled on the land which the French authorities had given to the Catholic church.

The construction of the camp next to the Lebanese Christian village

was planned on a

street grid.

The two village churches were incorporated into the camp.

During the works a number of Phoenician tombs were discovered.

One year later, another camp was constructed in the

El Bass area of Tyre.

In 1942,

Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

Maurice Chehab

Emir Maurice Hafez Chehab (27 December 1904 – 24 December 1994) was a Lebanese archaeologist and museum curator. He was the head of the Antiquities Service in Lebanon and curator of the National Museum of Beirut from 1942 to 1982. He was re ...

(1904-1994) - "the father of modern Lebanese archaeology" who for decades headed the Antiquities Service in Lebanon and was the curator of the

National Museum of Beirut

The National Museum of Beirut ( ar, متحف بيروت الوطنيّ, ''Matḥaf Bayrūt al-waṭanī'' or French: Musée national de Beyrouth) is the principal museum of archaeology in Lebanon. The collection begun after World War I, and the m ...

- conducted further excavations in Rashidieh and discovered more cinerary urns from Phoenician times.

Lebanese independence (since 1943)

1948 Palestinian exodus

When the state of

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

was declared in May 1948, the area of Tyre was immediately affected: with the

Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

exodus – also known as the

Nakba

Clickable map of Mandatory Palestine with the depopulated locations during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

The Nakba ( ar, النكبة, translit=an-Nakbah, lit=the "disaster", "catastrophe", or "cataclysm"), also known as the Palestinian Ca ...

– thousands of Palestinian refugees fled there, often by boat.

However, Rashidieh apparently continued to house Armenian refugees, while Palestinians were sheltered in a tented camp at

Burj el-Shemali for transit to other places in Lebanon.

"''In 1950, a couple of years after arriving in south Lebanon, the Lebanese authorities decided to relocate all Palestinians residing in southern towns (e.g., Tibnine, al-Mansouri, al-Qlayla, and Bint Jbeil) to designated refugee camps. The authorities established one of these camps adjacent to the Armenian camp with nothing but tents. The residents there began to build walls from mud and clay in order to reinforce the tents. For every eight housing units, they built a shared bathroom fifty meters away. A decade later, as Armenian residents began to leave, the Palestinian refugees began moving into those lots. 200 of the 311 Armenian houses remain today and are commonly referred to as the >Old Camp.<''"

In 1963, the

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) built a new section in Rashidieh to accommodate Palestine refugees from

Deir al-Qassi,

Alma,

Suhmata

Suhmata ( ar, سحماتا), was a Palestinian village, located northeast of Acre. It was depopulated by the Golani Brigade during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

History

Separated from the neighboring village of Tarshiha by a deep gorge, the r ...

,

Nahaf,

Fara and other villages in Palestine, who were relocated by the Lebanese government from the El Bass refugee camp and from

Baalbeck.

"''After the 1969 agreement in which the Lebanese government recognized the presence of the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and sta ...

(PLO) in Lebanon, and its control of the camps, the Rashidieh residents worked the Jaftalak fields surrounding the camp without paying any fees. Each farmer could choose a plot of land to plant and they would come to be (informally) known as the owner of that plot. The Jaftalak land was public land divided between the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Education, and other-defined state land. Yet the cultivation of Jaftalak fields was limited to greens: pinto beans, lettuce, parsley, cilantro, radishes, etc. The farmers were prohibited from growing fruit-bearing trees since the land did not legally belong to them. According to Lebanese property law, whoever plants a tree, automatically owns the land it is on.''"

In 1970, the camp received more Palestinian refugees, this time from

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

following the

Black September

Black September ( ar, أيلول الأسود; ''Aylūl Al-Aswad''), also known as the Jordanian Civil War, was a conflict fought in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan between the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF), under the leadership of King Hussein ...

conflict between

Jordanian Armed Forces

The Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) ( ar, الْقُوَّاتُ الْمُسَلَّحَةُ الأرْدُنِية, romanized: ''Al-Quwwat Al-Musallaha Al-Urduniyya''), also referred to as the Arab Army ( ar, الْجَيْشُ الْعَرَب� ...

(JAF) under

King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

and the PLO led by

Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

.

Rashidieh increasingly became an important recruitment and training center for

Al-'Asifah, the armed wing of Arafat's

Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and s ...

faction.

In 1974, the Israeli military attacked: on May 19, the

Israeli Navy

The Israeli Navy ( he, חיל הים הישראלי, ''Ḥeil HaYam HaYisraeli'' (English: The Israeli Sea Corps); ar, البحرية الإسرائيلية) is the naval warfare service arm of the Israel Defense Forces, operating primarily in ...

reportedly shelled Rashidieh, killing 5 people and injuring 11. On 20 June, the

Israeli Air Force

The Israeli Air Force (IAF; he, זְרוֹעַ הָאֲוִיר וְהֶחָלָל, Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal, tl, "Air and Space Arm", commonly known as , ''Kheil HaAvir'', "Air Corps") operates as the aerial warfare branch of the Israel Defens ...

(IAF) bombed the camp. According to the Lebanese army, 5 people were killed and 21 injured in Rashidieh.

In the same year, "''a rescue excavation''" was conducted in Rashidieh by Lebanon's Department of Antiquities after a mechanical digger was used to build a shelter and five Iron Age tombs were discovered.

Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990)

In January 1975, a unit of the

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary so ...

(PFLP) attacked the Tyre barracks of the Lebanese Army.

The assault was denounced by the PLO as "''a premeditated and reckless act''".

Two months later, a PLO commando of eight militants sailed from the coast of Tyre to

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

to mount the

Savoy Hotel attack

The Savoy Hotel attack was a terrorist attack by the Palestine Liberation Organization against the Savoy Hotel in Tel Aviv, Israel, on 4–5 March 1975.

Background

The operation was planned by Abu Jihad.

Initial Palestinian planning had cal ...

, during which eight civilian

Hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or refr ...

s and three Israeli soldiers were killed as well as seven of the attackers. Israel retaliated by launching a string of attacks on Tyre "''from land, sea and air''" in August and September 1975.

Then, in 1976, local commanders of the PLO took over the municipal government of Tyre with support from their allies of the

Lebanese Arab Army

The Lebanese Arab Army – LAA (Arabic: جيش لبنان العربي transliteration ''Jayish Lubnan al-Arabi''), also known as the Arab Army of Lebanon (AAL), Arab Lebanese Army or Armée du Liban Arabe (ALA) in French, was a predominantly M ...

.

They occupied the army barracks, set up roadblocks and started collecting customs at the port. However, the new rulers quickly lost support from the Lebanese-Tyrian population because of their "''

arbitrary

Arbitrariness is the quality of being "determined by chance, whim, or impulse, and not by necessity, reason, or principle". It is also used to refer to a choice made without any specific criterion or restraint.

Arbitrary decisions are not necess ...

and often brutal behavior''".

In 1977, three Lebanese

fishermen

A fisher or fisherman is someone who captures fish and other animals from a body of water, or gathers shellfish.

Worldwide, there are about 38 million commercial and subsistence fishers and fish farmers. Fishers may be professional or recreati ...

in Tyre lost their lives in an Israeli attack. Palestinian militants retaliated with rocket fire on the Israeli town of

Nahariya

Nahariya ( he, נַהֲרִיָּה, ar, نهاريا) is the northernmost coastal city in Israel. In it had a population of .

Etymology

Nahariya takes its name from the stream of Ga'aton (river is ''nahar'' in Hebrew), which bisects it.

His ...

, leaving three civilians dead. Israel in turn retaliated by killing "''over a hundred''" mainly Lebanese Shiite civilians in the Southern Lebanese countryside. Some sources reported that these lethal events took place in July,

whereas others dated them to November. According to the latter, the IDF also conducted heavy airstrikes as well as artillery and gunboat shelling on Tyre and surrounding villages, but especially on the Palestinian refugee camps in Rashidieh, Burj El Shimali and El Bass.

= 1978 South Lebanon conflict with Israel

=

On 11 March 1978,

Dalal Mughrabi – a young woman from the Palestinian refugee camp of Sabra in Beirut – and a dozen

Palestinian fedayeen

Palestinian fedayeen (from the Arabic ''fidā'ī'', plural ''fidā'iyūn'', فدائيون) are militants or guerrillas of a nationalist orientation from among the Palestinian people. Most Palestinians consider the fedayeen to be " freedom fig ...

fighter sailed from Tyre to a beach north of Tel Aviv. Their attacks on civilian targets became known as the

Coastal Road massacre that killed 38 Israeli civilians, including 13 children, and wounded 71.

According to the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

,

PLO ''"claimed responsibility for that raid. In response, Israeli forces invaded Lebanon on the night of 14/15 March, and in a few days occupied the entire southern part of the country except for the city of Tyre and its surrounding area."''

Tyre was badly affected in the fighting during the

Operation Litani

The 1978 South Lebanon conflict (codenamed Operation Litani by Israel) began after Israel invaded southern Lebanon up to the Litani River in March 1978, in response to the Coastal Road massacre near Tel Aviv by Lebanon-based Palestinian ...

, with civilians bearing the brunt of the war, both in human lives and economically:

The

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

(IDF) targeted especially the harbour on claims that the PLO received arms from there and the Palestinian refugee camps.

On 19 March, the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

adopted resolutions in which decided on the immediate establishment of the

United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon ( ar, قوة الأمم المتحدة المؤقتة في لبنان, he, כוח האו"ם הזמני בלבנון), or UNIFIL ( ar, يونيفيل, he, יוניפי״ל), is a UN peacekeeping m ...

(UNIFIL). Its first troops arrived in the area four days later.

However, the Palestinian forces were unwilling to give up their positions in and around Tyre. UNIFIL was unable to expel those militants and sustained heavy casualties. It therefore accepted an

enclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of Palestinian fighters in its area of operation which was dubbed the "Tyre Pocket". In effect, the PLO kept ruling Tyre with its Lebanese allies of the

National Lebanese Movement, which was in disarray though after the 1977 assassination of its leader

Kamal Jumblatt.

Frequent IDF bombardments of Tyre from ground, sea and air raids continued after 1978.

The PLO, on the other side, reportedly converted itself into a regular army by purchasing large weapon systems, including

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

WWII-era

T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank introduced in 1940. When introduced its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was less powerful than its contemporaries while its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against anti-tank weapons. The C ...

tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

s, which it deployed in the "Tyre Pocket" with an estimated 1,500 fighters.

From there, and the area around Rashidieh in particular, it kept firing

Katyusha rockets

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area ...

across the Southern border

into Galilee until a cease-fire in July 1981.

As discontent within the Shiite population about the suffering from the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian factions grew, so did the tensions between the

Amal Movement - the dominant Shia-party - and the Palestinian militants.

The power struggle was exacerbated by the fact that the PLO supported

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

's camp during the

Iraq-Iran-War, whereas Amal sided with Teheran. Eventually, the

political polarisation

Political polarization (spelled ''polarisation'' in British English) is the divergence of political attitudes away from the center, towards ideological extremes.

Most discussions of polarization in political science consider polarization in the c ...

between the former allies escalated into violent clashes in many villages of Southern Lebanon, including the Tyre area.

= 1982 Lebanon War with Israel and Occupation

=

Following an

assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

attempt on Israeli ambassador

Shlomo Argov

Shlomo Argov ( he, שלמה ארגוב; 14 December 1929 – 23 February 2003) was an Israeli diplomat. He was the Israeli ambassador to the United Kingdom whose attempted assassination led to the 1982 Lebanon War.

Early life and education

Arg ...

in London the IDF

invaded Lebanon on 6 June 1982, with heavy fighting in and around Tyre. The first target of the invaders was Rashidieh.

There were 15,356 registered Palestinian refugees in the camp at the time, but

John Bulloch, then the Beirut-based correspondent of

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

, estimated that it actually housed more than 30,000. Most civilians fled into underground tunnels and bomb shelters, while Palestinian fighters tried to hold off the Israeli army. The militants, however, came under massive fire from air strikes, gunboats and artillery. Bulloch reported that the IDF also dropped

US-supplied

cluster bombs and shells on Rashidieh.

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky i ...

recorded that already by the second day much of Rashidieh "''had become a field of

rubble

Rubble is broken stone, of irregular size, shape and texture; undressed especially as a filling-in. Rubble naturally found in the soil is known also as 'brash' (compare cornbrash)."Rubble" def. 2., "Brash n. 2. def. 1. ''Oxford English Dictionar ...

''." he quoted a UNIFIL officer as commenting: ''"It was like shooting sparrows with cannon.''" On the fourth day, many civilians reportedly left their shelters waving white flags. Those who remained suffered for three more days,

until the last

guerillas

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tacti ...

were defeated.

Bulloch writes that the Israelis lost nine men.

The volunteer

nurse

Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health ...

Françoise Kesteman, who was a member of the

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European ...

, recounted as exemplary the death of a young Palestinian mother:

"''When Mouna left the bomb shelter to fetch food for the children, Israeli bombers ripped apart her small slender body.''"

For Kesteman, the bloodbath was a turning-point in her life and she joined the Palestinian guerillas after a brief return to France. She was killed two years later when she participated in an attempted attack on Israeli targets off the coast, making her the first French national to die fighting for the Palestinian militants.

When the fighting stopped after one week, more destruction was done ''"systematically''",

as the IDF brought in

bulldozer

A bulldozer or dozer (also called a crawler) is a large, motorized machine equipped with a metal blade to the front for pushing material: soil, sand, snow, rubble, or rock during construction work. It travels most commonly on continuous track ...

s. According to Bulloch, the occupation forces not only barred international correspondents from visiting the camp, but they also refused to allow the delegates of the

International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

(ICRC) any access for five weeks.

Subsequently, the

Christian Science Monitor

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρισ ...

estimated that about sixty percent of the camp were destroyed with some 5,000 refugees living in the ruins:

"''Israeli soldiers dynamited air raid shelters built by the Palestine Liberation Organization. The shelters were scattered throughout the camp and their demolition resulted in the destruction of surrounding houses as well''. '' .Many other houses were bulldozed, according to camp residents and UNRWA workers, creating wide swaths leading to the sea.''"

The Israeli forces then made mass arrests, including women.

The male detainees were paraded in front of

hooded

A hood is a kind of headgear that covers most of the head and neck, and sometimes the face. Hoods that cover mainly the sides and top of the head, and leave the face mostly or partly open may be worn for protection from the environment (typica ...

collaborators who advised the occupation forces whom to detain.

Bulloch reported that

"''busloads of handcuffed and blindfolded suspects were taken off for interrogation. These men were denied the small comfort of International Red Cross visits since they were not considered prisoners of war, but 'administrative detainees."

Thus, the IDF obliterated Rashidieh as the main center of Palestinian operations into Upper Galilee. However, in the following three years, their occupation forces in the Tyre area came instead under the growing pressure from a number of devastating

suicide attack

A suicide attack is any violent attack, usually entailing the attacker detonating an explosive, where the attacker has accepted their own death as a direct result of the attacking method used. Suicide attacks have occurred throughout histor ...

s by Amal and - even more so - its emerging split-off

Hezbollah

Hezbollah (; ar, حزب الله ', , also transliterated Hizbullah or Hizballah, among others) is a Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and militant group, led by its Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah since 1992. Hezbollah's parami ...

. By the end of April 1985, the Israelis withdrew from Tyre and instead established a self-declared "

Security Zone" in Southern Lebanon with its collaborating militia allies of the

South Lebanon Army (SLA):

= 1985-1988 War of the Camps: Amal vs. PLO

=

Tyre was 8km beyond the security zone and taken over by

Amal under the leadership of

Nabih Berri

Nabih Berri ( ar, نبيه مصطفى بري, translit=Nabīh Muṣṭafā Barriyy, links=hh; born 28 January 1938) is a Lebanese Shia politician who has been serving as Speaker of the Parliament of Lebanon since 1992. He heads the Amal Moveme ...

.

"''The priority of Amal remained to prevent the return of any armed Palestinian presence to the South, primarily because this might provoke renewed Israeli intervention in recently evacuated areas. The approximately 60,000 Palestinian refugees in the camps around Tyre (al-Bass, Rashidiya, Burj al-Shimali) were cut off from the outside world, although Amal never succeeded in fully controlling the camps themselves. In the Sunni 'canton' of Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

, the armed PLO returned in force.''"

Tensions between Amal and Palestinian militants soon exploded into the

War of the Camps

The War of the Camps ( ar, حرب المخيمات, ''Harb al-mukhayimat''), was a subconflict within the 1984–1990 phase of the Lebanese Civil War, in which the Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut were besieged by the Shia Amal militia. ...

, which is considered as "''one of the most brutal episodes in a brutal civil war''":

In September 1986, a group of Palestinians fired on an Amal patrol at Rashidieh. At the end of September Amal imposed a blockade on the camp. After one month of siege, Amal attacked the camp.

It was reportedly assisted by the

Progressive Socialist Party

The Progressive Socialist Party ( ar, الحزب التقدمي الاشتراكي, translit=al-Hizb al-Taqadummi al-Ishtiraki) is a Lebanese political party. Its confessional base is in the Druze sect and its regional base is in Mount Lebanon ...

of Druze leader

Walid Jumblatt

Walid Kamal Jumblatt ( ar, وليد جنبلاط; born 7 August 1949) is a Lebanese Druze politician and former militia commander who has been leading the Progressive Socialist Party since 1977. While leading the Lebanese National Resistance ...

as well as by the pro-Syrian Palestinian militias of

As-Saiqa

As-Sa'iqa ( ar, صاعقة, lit=Thunderbolt, translit=Saiqa) officially known as Vanguard for the Popular Liberation War - Lightning Forces, ( ar, طلائع حرب التحرير الشعبية - قوات الصاعقة ) is a Palestinian Ba' ...

and the "

".

Fighting spread and continued for one month.

In the words of one Palestinian woman from Rashidieh,

"''Amal .did the same things that the Israelis did.''"

UNRWA recorded that between 1982 and 1987 in Rashidieh

"''more than 600 shelters were totally or partially destroyed and more than 5,000 Palestine refugees were displaced.''"

By the end of November, with the fighting having spread to Sidon and Beirut, four small camps in Tyre had been destroyed with an estimated 18,000 residents fleeing to the

Beqaa Beqaa ( ar, بقاع, link=no, ''Biqā‘'') can refer to two places in Lebanon:

* Beqaa Governorate, one of six major subdivisions of Lebanon

* Beqaa Valley, a valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region

See also

*Kasbeel ...

. On 24 November the Palestinian factions in Sidon launched an offensive against Amal positions in the strategic village of

Maghdouché in an attempt to cut Amal forces around Rashidieh off from their stronghold in West Beirut. Rashidieh was able to withstand the siege better than the camps in Beirut since food was reaching the camp by sea. By the end of the year 8,000 Palestinians had fled to

Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

which was not under Amal control. Around a 1,000 men had been kidnapped from the camps in Tyre.

The conflict ended with the withdrawal of Palestinian forces loyal to PLO leader Arafat from Beirut and their redeployment to the camps in Southern Lebanon. The one in Rashidieh likewise continued to be the "''main stronghold''" of Arafat's Fatah party and loyalist contingents of other PLO factions, though some forces opposed to them - including

Islamists

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern states and regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, economic and judicial terms, in accordance with what is c ...

- kept a presence and representation there as well.

In February 1988, "''Amal seemed to lose control''" when US-Colonel

William R. Higgins, who served in a senior position of the

United Nations Truce Supervision Organization

The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) is an organization founded on 29 May 1948 for peacekeeping in the Middle East. Established amidst the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, its primary task was initially to provide the military co ...

(UNTSO), was kidnapped on the coastal highway to

Naqoura

Naqoura (, ''Enn Nâqoura, Naqoura, An Nāqūrah'') is a small city in southern Lebanon. Since March 23, 1978, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) has been headquartered in Naqoura.

Name

According to E. H. Palmer (1881), the nam ...

close to Rashidieh by armed men suspected of being affiliated with Hezbollah. The incident took place following a meeting between Higgins and a local Amal leader and led to renewed clashes between Amal and Hezbollah, mainly in Beirut.

Throughout the war, clandestine excavations were conducted in Rashidieh. Many cinerary urns from Phoenician times thus ended up in private collections without any documentation.

In addition, Rashidieh's beach was subject to sand grabbing and suction.

Post-Civil War (since 1990)

On 14 June 1990 fierce fighting broke out in the Rashidieh Camp between two factions of the

Abu Nidal Organization

The Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) is the most common name for the Palestinian nationalist militant group Fatah – The Revolutionary Council (''Fatah al-Majles al-Thawry''). The ANO is named after its founder Abu Nidal. It was created by a spli ...

. The clashes lasted two days with three killed and 15 wounded. Amongst the dead was the leader of the

Abu Nidal

Sabri Khalil al-Banna (May 1937 – 16 August 2002), known by his '' nom de guerre'' Abu Nidal, was the founder of Fatah: The Revolutionary Council, a militant Palestinian splinter group more commonly known as the Abu Nidal Organization ...

loyalists in the Camp. His followers evacuated to

Ain al-Hilwa Camp.

An Israeli air strike on Rashidieh, 24 October 1990, caused 5 casualties and destroyed a school.

Following the end of the war in March 1991 based on the

Taif Agreement

The Taif Agreement ( ar, اتفاق الطائف), officially known as the ( ar, وثيقة الوفاق الوطني, label=none'')'', was reached to provide "the basis for the ending of the civil war and the return to political normalcy in Le ...

, units of the Lebanese Army deployed along the coastal highway and around the Palestinian refugee camps of Tyre.

By the end of the 1990s, the Coalition of Fatah with the

Palestinian Liberation Front (PLF),

Palestinian Popular Struggle Front (PPSF), and the

Palestinian People's Party (PPP) in Lebanon was headed by

Sultan Abu al-'Aynayn, who resided in Rashidieh.

In 1999, he was sentenced to death in absentia by the Lebanese authorities for inciting armed rebellion and damaging the property of the Lebanese state.

At the time of Israel's invasion in the

July 2006 Lebanon War, the camp had about 18,000 residents. Reportedly, more than 1,000 Lebanese fled their homes to seek shelter in Rashidieh during the Israeli bombardments of Southern Lebanon:

"''It's kind of an irony really. It's almost a joke what's going on,"'' said Ibrahim al-Ali, a 26-year-old Palestinian social worker in the camp. ''"The irony is that refugees are accepting citizens from their own country.''"

However, on 8 August 2006, the area of Rashidieh was hit by Israeli attack as well.

In May 2020, clashes in Rashidieh left one person dead and five others injured.

On 14 May 2021, shortly after the beginning of the

2021 Israel–Palestine crisis

A major outbreak of violence in the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict commenced on 10 May 2021, though disturbances took place earlier, and continued until a ceasefire came into effect on 21 May. It was marked by protests and police riot ...

, the Lebanese Army issued a statement saying that they had found three rockets in the Rashidieh area, but that the discovery was not linked to the launch of a number of rockets - apparently Soviet-era short-range

Grad projectiles - from the nearby coastal area belonging to the

Qlaileh village a day earlier.

Economy

Almost half of those residents of Rashidieh who are in work do

low-paid seasonal or occasional jobs on

construction sites

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form objects, systems, or organizations,"Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press 2009 and co ...

or as

agricultural labourers in the

banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", disting ...

,

lime and

orange orchard

An orchard is an intentional plantation of trees or shrubs that is maintained for food production. Orchards comprise fruit- or nut-producing trees which are generally grown for commercial production. Orchards are also sometimes a feature of ...

s of the region.

Cultural life

Unlike most other Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, which also house some non-Palestinian residents and Palestinian Christian families, Rashidieh is assumed to be populated entirely by Muslim Palestinians. The two old village churches, which were both partially destroyed during the civil war, are now used for storage.