Rangaku on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Rangaku'' (

''Rangaku'' ( Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of the scientific and technological revolution occurring in

Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of the scientific and technological revolution occurring in

The

The

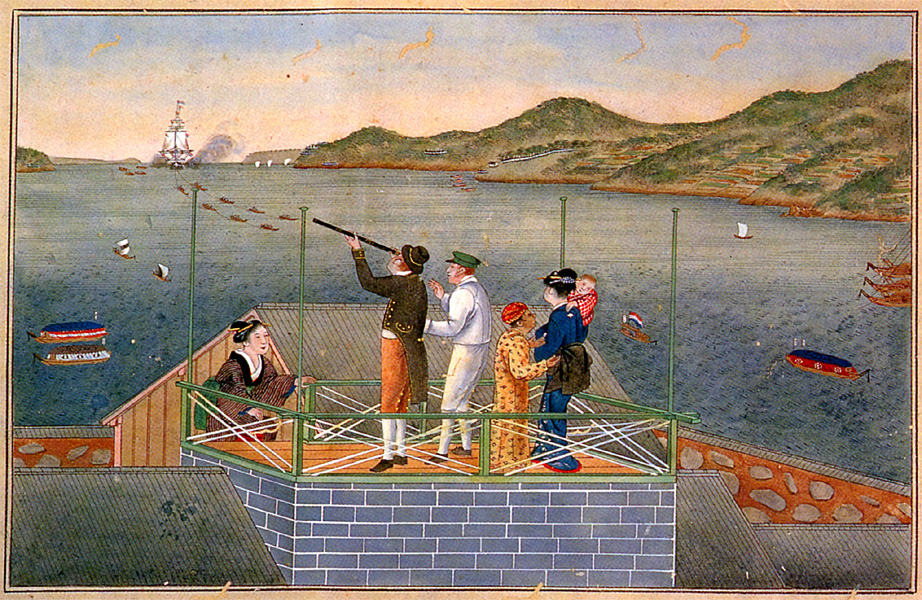

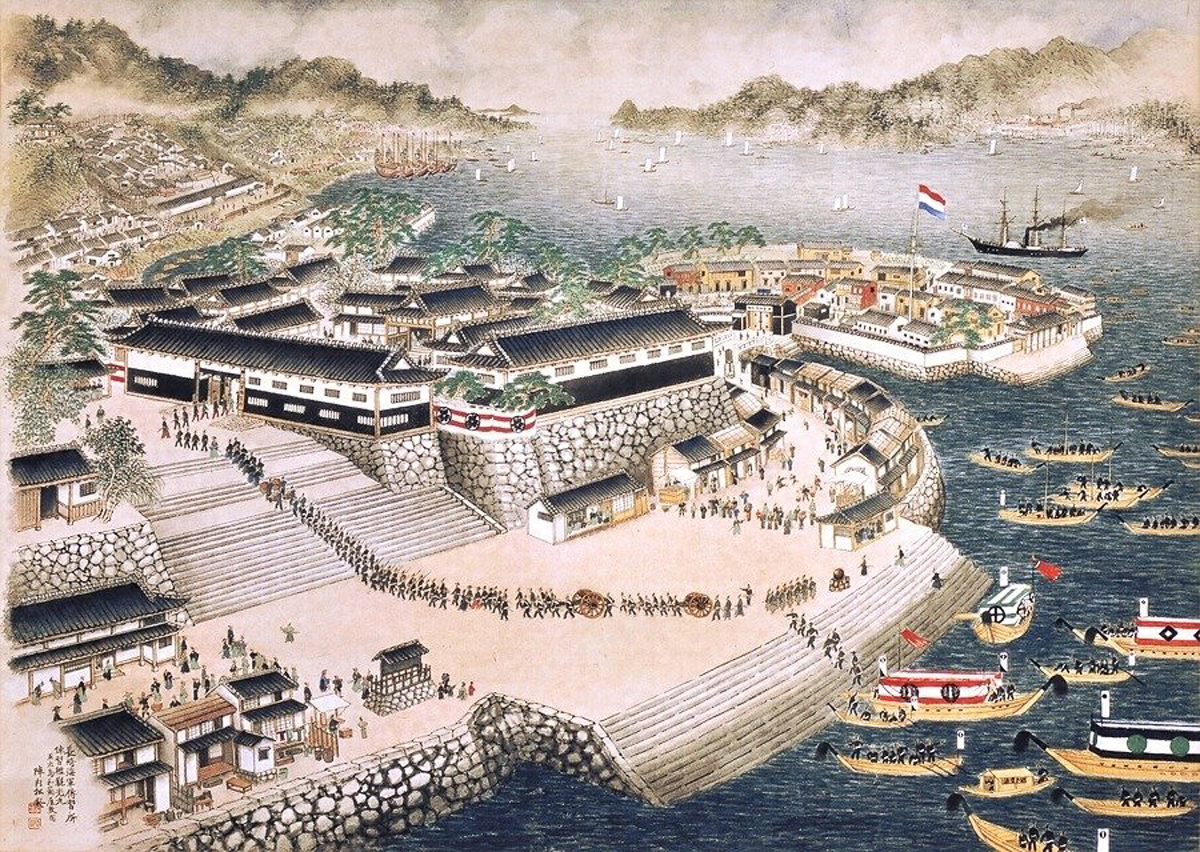

The first phase of Rangaku was quite limited and highly controlled. After the relocation of the Dutch trading post to

The first phase of Rangaku was quite limited and highly controlled. After the relocation of the Dutch trading post to

Although most Western books were forbidden from 1640, rules were relaxed under ''

Although most Western books were forbidden from 1640, rules were relaxed under ''

From around 1720, books on medical sciences were obtained from the Dutch, and then analyzed and translated into Japanese. Great debates occurred between the proponents of

From around 1720, books on medical sciences were obtained from the Dutch, and then analyzed and translated into Japanese. Great debates occurred between the proponents of  In 1804,

In 1804,

Electrical experiments were widely popular from around 1770. Following the invention of the

Electrical experiments were widely popular from around 1770. Following the invention of the

In 1840, Udagawa Yōan published his , a compilation of scientific books in Dutch, which describes a wide range of scientific knowledge from the West. Most of the Dutch original material appears to be derived from William Henry’s 1799 ''Elements of Experimental Chemistry''. In particular, the book contains a detailed description of the

In 1840, Udagawa Yōan published his , a compilation of scientific books in Dutch, which describes a wide range of scientific knowledge from the West. Most of the Dutch original material appears to be derived from William Henry’s 1799 ''Elements of Experimental Chemistry''. In particular, the book contains a detailed description of the

Japan's first

Japan's first

File:Kunitomo1832Telescope.jpg, Kunitomo's

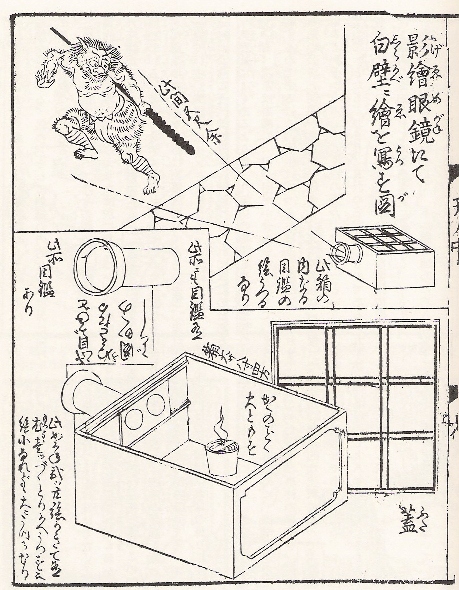

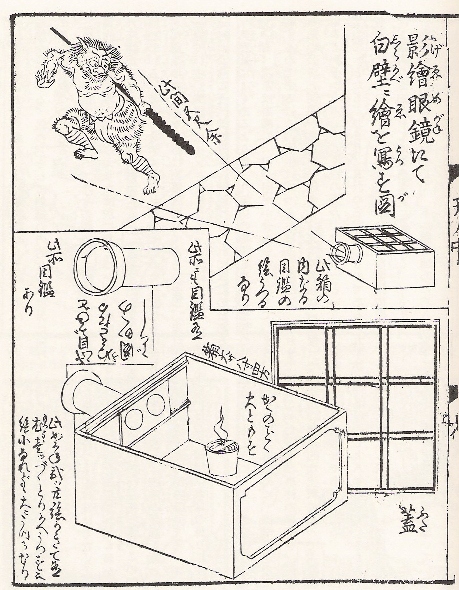

Magic lanterns, first described in the West by

Magic lanterns, first described in the West by

Air pump mechanisms became popular in Europe from around 1660 following the experiments of

Air pump mechanisms became popular in Europe from around 1660 following the experiments of

File:Gyusengekisui.jpg, Kunitomo's "Aspiration pump driven by an ox" (1810 advertisement)

File:KunitomoAirGunMechanism.jpg, Air gun trigger mechanism

The first flight of a

The first flight of a

Knowledge of the

Knowledge of the

Modern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints of Matteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima. This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries. With this knowledge,

Modern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints of Matteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima. This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries. With this knowledge,

The description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by the Encyclopedists and promoted by von Siebold (a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima). Itō Keisuke created books describing animal species of the Japanese islands, with drawings of a near-photographic quality.

The description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by the Encyclopedists and promoted by von Siebold (a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima). Itō Keisuke created books describing animal species of the Japanese islands, with drawings of a near-photographic quality.

When Commodore Perry obtained the signature of treaties at the

When Commodore Perry obtained the signature of treaties at the

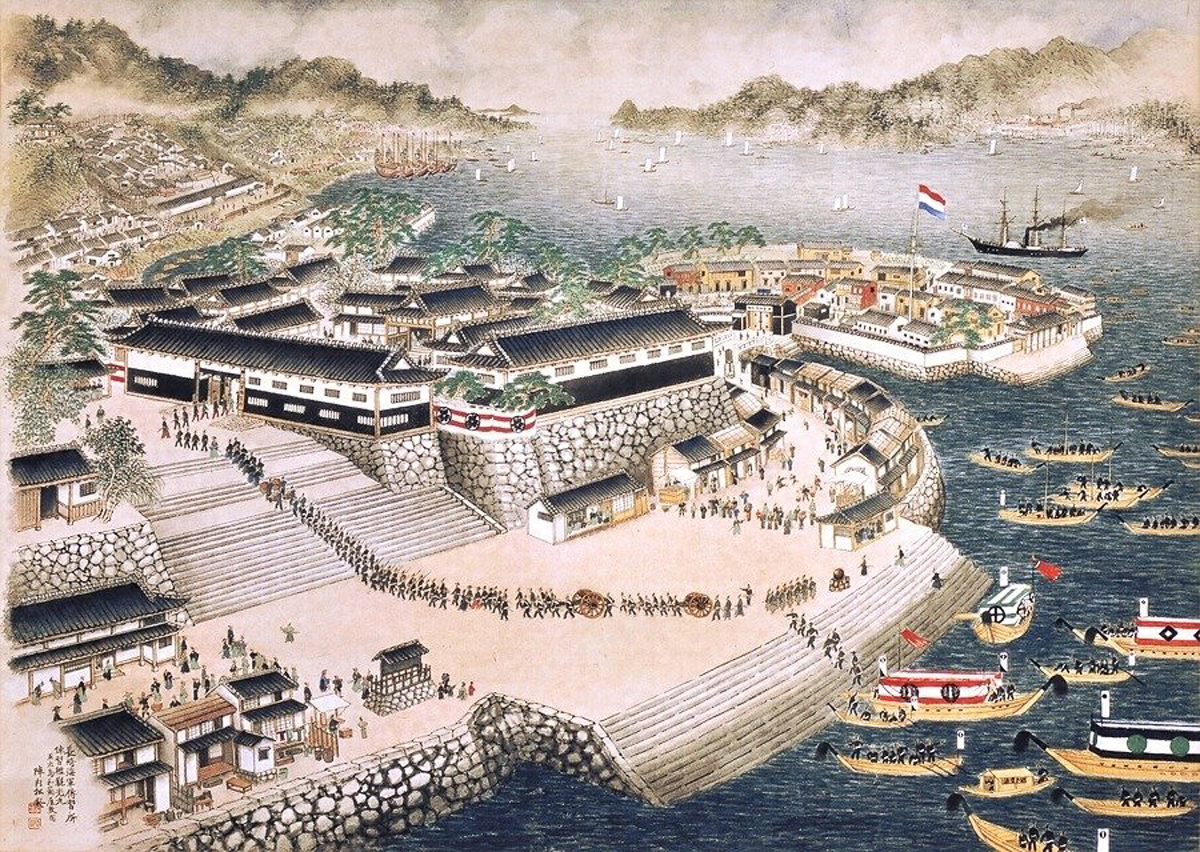

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Netherlands continued to have a key role in transmitting Western know-how to Japan for some time. The Bakufu relied heavily on Dutch expertise to learn about modern Western shipping methods. Thus, the

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Netherlands continued to have a key role in transmitting Western know-how to Japan for some time. The Bakufu relied heavily on Dutch expertise to learn about modern Western shipping methods. Thus, the

*

*

Kyūjitai

''Kyūjitai'' ( ja, 舊字體 / 旧字体, lit=old character forms) are the traditional forms of kanji, Chinese written characters used in Japanese. Their simplified counterparts are ''shinjitai'' ( ja, 新字体, lit=new character forms, lab ...

: /Shinjitai

are the simplified forms of kanji used in Japan since the promulgation of the Tōyō Kanji List in 1946. Some of the new forms found in ''shinjitai'' are also found in Simplified Chinese characters, but ''shinjitai'' is generally not as extensiv ...

: , literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning") is a body of knowledge developed by Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, i ...

, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

in the period when the country was closed to foreigners from 1641 to 1853 because of the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

's policy of national isolation (sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

).

Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of the scientific and technological revolution occurring in

Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of the scientific and technological revolution occurring in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

at that time, helping the country build up the beginnings of a theoretical and technological scientific base, which helps to explain Japan's success in its radical and speedy modernization following the forced American opening of the country to foreign trade in 1854.

History

The

The Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

traders at Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, i ...

in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

were the only Europeans tolerated in Japan from 1639 until 1853 (the Dutch had a trading post in Hirado

is a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. The part historically named Hirado is located on Hirado Island. With recent mergers, the city's boundaries have expanded, and Hirado now occupies parts of the main island of Kyushu. The component ...

from 1609 till 1641 before they had to move to Dejima), and their movements were carefully watched and strictly controlled, being limited initially to one yearly trip to give their homage to the ''shōgun'' in Edo. They became instrumental, however, in transmitting to Japan some knowledge of the industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

and scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

that was occurring in Europe: the Japanese purchased and translated scientific books from the Dutch, obtained from them Western curiosities and manufactures (such as clocks, medical instruments, celestial and terrestrial globes, maps and plant seeds) and received demonstrations of Western innovations, including of electrical phenomena, as well as the flight of a hot air balloon in the early 19th century. While other European countries faced ideological and political battles associated with the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the Netherlands were a free state, attracting leading thinkers such as René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

.

Altogether, thousands of such books were published, printed, and circulated. Japan had one of the largest urban populations in the world, with more than one million inhabitants in Edo, and many other large cities such as Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

and Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

, offering a large, literate market to such novelties. In the large cities some shops, open to the general public, specialized in foreign curiosities.

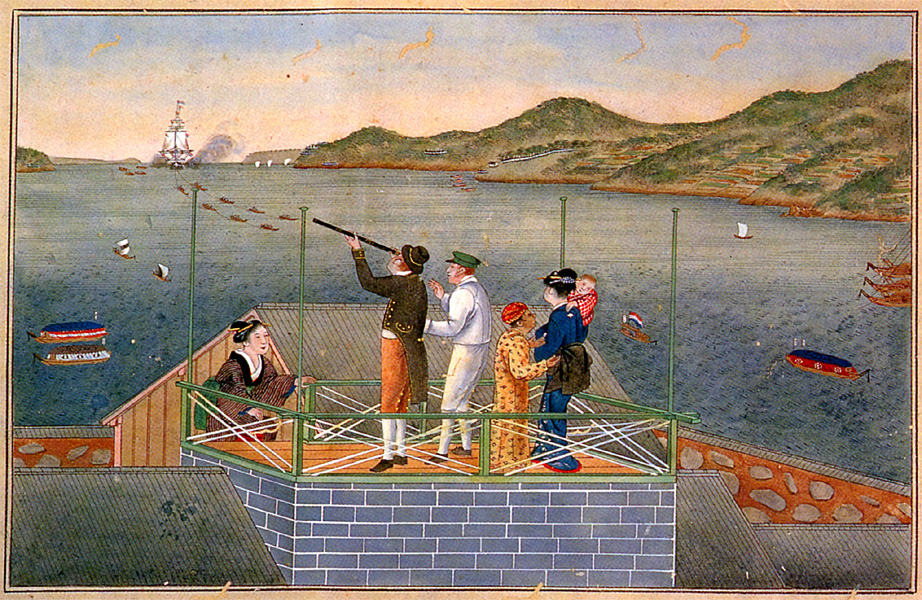

Beginnings (1640–1720)

The first phase of Rangaku was quite limited and highly controlled. After the relocation of the Dutch trading post to

The first phase of Rangaku was quite limited and highly controlled. After the relocation of the Dutch trading post to Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, i ...

, trade as well as the exchange of information and the activities of the remaining Westerners (dubbed "Red-Heads" (''kōmōjin'')) were restricted considerably. Western books were prohibited, with the exemption of books on nautical and medical matters. Initially, a small group of hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

Japanese–Dutch translators labored in Nagasaki to smooth communication with the foreigners and transmit bits of Western novelties.

The Dutch were requested to give updates of world events and to supply novelties to the ''shōgun'' every year on their trips to Edo. Finally, the Dutch factories in Nagasaki, in addition to their official trade work in silk and deer hides, were allowed to engage in some level of "private trade". A small, lucrative market for Western curiosities thus developed, focused on the Nagasaki area. With the establishment of a permanent post for a surgeon at the Dutch trading post Dejima, high-ranking Japanese officials started to ask for treatment in cases when local doctors were of no help. One of the most important surgeons was Caspar Schamberger, who induced a continuing interest in medical books, instruments, pharmaceuticals, treatment methods etc. During the second half of the 17th century high-ranking officials ordered telescopes, clocks, oil paintings, microscopes, spectacles, maps, globes, birds, dogs, donkeys, and other rarities for their personal entertainment and for scientific studies.

Liberalization of Western knowledge (1720–)

Although most Western books were forbidden from 1640, rules were relaxed under ''

Although most Western books were forbidden from 1640, rules were relaxed under ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'' Tokugawa Yoshimune

was the eighth ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, ruling from 1716 until his abdication in 1745. He was the son of Tokugawa Mitsusada, the grandson of Tokugawa Yorinobu, and the great-grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Lineage

Yoshimu ...

in 1720, which started an influx of Dutch books and their translations into Japanese. One example is the 1787 publication of Morishima Chūryō’s , recording much knowledge received from the Dutch. The book details a vast array of topics: it includes objects such as microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

s and hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

s; discusses Western hospitals and the state of knowledge of illness and disease; outlines techniques for painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ...

and printing with copper plates; it describes the makeup of static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material or between materials. The charge remains until it is able to move away by means of an electric current or electrical discharge. Static electricity is na ...

generators and large ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

s; and it relates updated geographical knowledge.

Between 1804 and 1829, schools opened throughout the country by the Shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

(Bakufu) as well as ''terakoya

were private educational institutions that taught reading and writing to the children of Japanese commoners during the Edo period.

History

The first ''terakoya'' made their appearance at the beginning of the 17th century, as a development from ...

'' (temple schools) helped spread the new ideas further.

By that time, Dutch emissaries and scientists were allowed much more free access to Japanese society. The German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (17 February 1796 – 18 October 1866) was a German physician, botanist and traveler. He achieved prominence by his studies of Japanese flora (plants), flora and fauna (animals), fauna and the introduction of ...

, attached to the Dutch delegation, established exchanges with Japanese students. He invited Japanese scientists to show them the marvels of Western science, learning, in return, much about the Japanese and their customs. In 1824, von Siebold began a medical school in the outskirts of Nagasaki. Soon this grew into a meeting place for about fifty students from all over the country. While receiving a thorough medical education they helped with the naturalistic studies of von Siebold.

Expansion and politicization (1839–)

The Rangaku movement became increasingly involved in Japan's political debate over foreign isolation, arguing that the imitating of Western culture would strengthen rather than harm Japan. The Rangaku increasingly disseminated contemporary Western innovations. In 1839, scholars of Western studies (called 蘭学者 "''rangaku-sha''") briefly suffered repression by the Edo shogunate in the incident, due to their opposition to the introduction of thedeath penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

against foreigners (other than Dutch) coming ashore, recently enacted by the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

. The incident was provoked by actions such as the Morrison Incident

The of 1837 occurred when the American merchant ship, ''Morrison'' headed by Charles W. King, was driven away from " sakoku" (isolationist) Japan by cannon fire. This was carried out in accordance with the Japanese Edict to Repel Foreign Vesse ...

, in which an unarmed American merchant ship was fired upon under the Edict to Repel Foreign Ships. The edict was eventually repealed in 1842.

Rangaku ultimately became obsolete when Japan opened up during the last decades of the Tokugawa regime (1853–67). Students were sent abroad, and foreign employees (o-yatoi gaikokujin

The foreign employees in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as ''O-yatoi Gaikokujin'' ( Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: , "hired foreigners"), were hired by the Japanese government and municipalities for their specialized knowledge and skill to assist in the ...

) came to Japan to teach and advise in large numbers, leading to an unprecedented and rapid modernization of the country.

It is often argued that Rangaku kept Japan from being completely uninformed about the critical phase of Western scientific advancement during the 18th and 19th century, allowing Japan to build up the beginnings of a theoretical and technological scientific base. This openness could partly explain Japan's success in its radical and speedy modernization following the opening of the country to foreign trade in 1854.

Types

Medical sciences

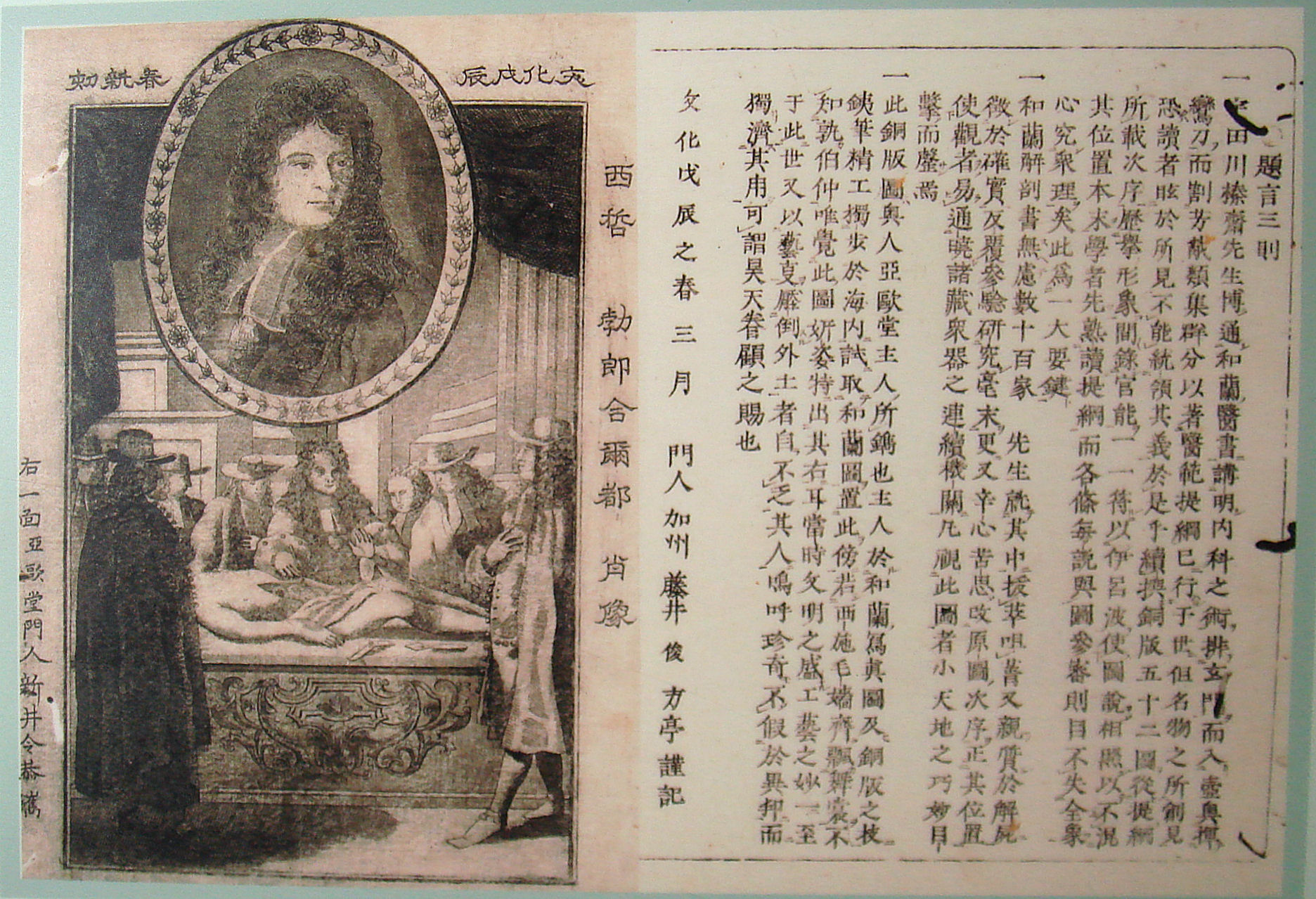

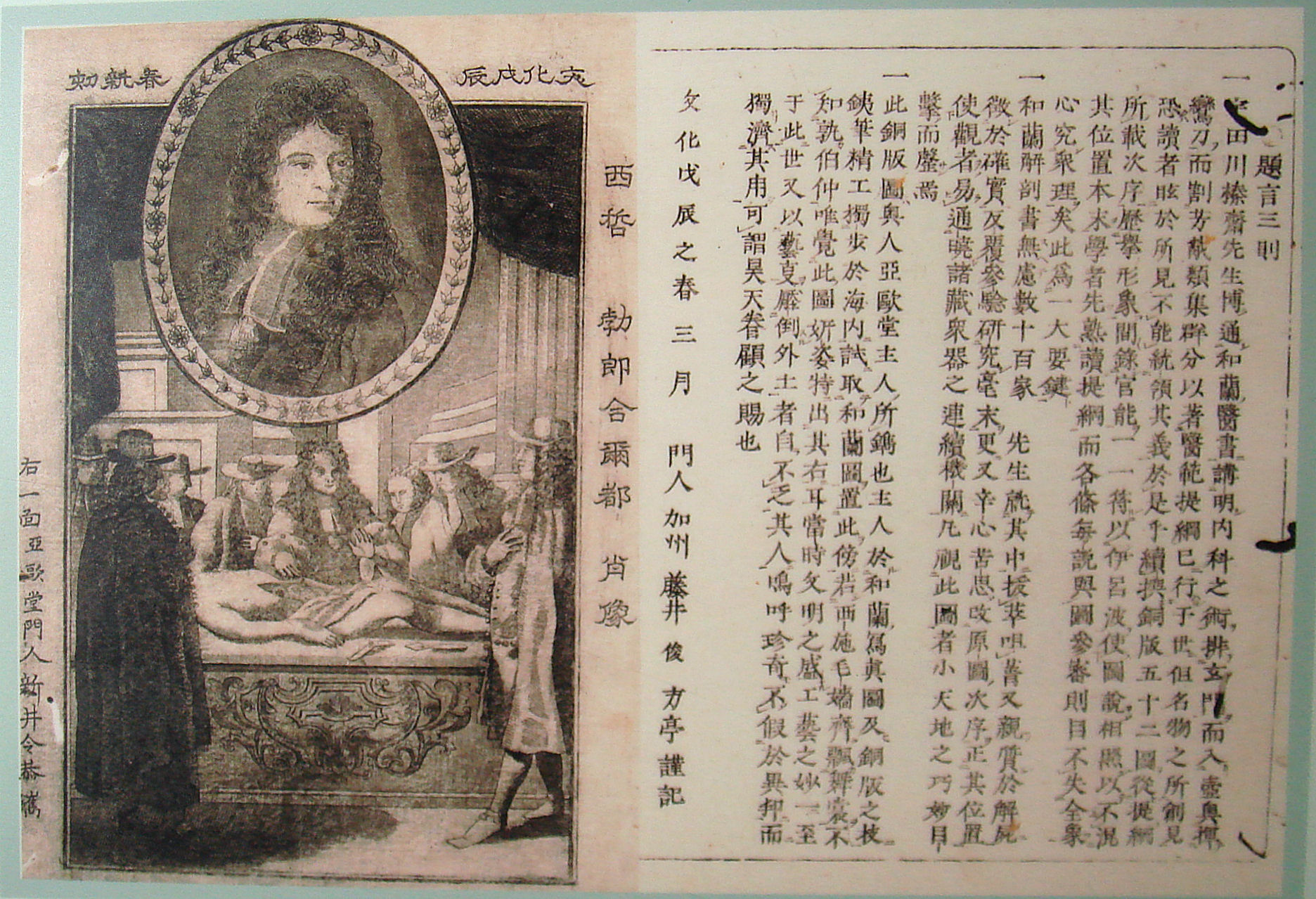

From around 1720, books on medical sciences were obtained from the Dutch, and then analyzed and translated into Japanese. Great debates occurred between the proponents of

From around 1720, books on medical sciences were obtained from the Dutch, and then analyzed and translated into Japanese. Great debates occurred between the proponents of traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. It has been described as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical mechanism of action ...

and those of the new Western learning, leading to waves of experiments and dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

s. The accuracy of Western learning made a sensation among the population, and new publications such as the of 1759 and the of 1774 became references. The latter was a compilation made by several Japanese scholars, led by Sugita Genpaku

was a Japanese physician and scholar known for his translation of ''Kaitai Shinsho'' (New Book of Anatomy) and a founder of ''Rangaku'' (Western learning) and ''Ranpō'' (Dutch style medicine) in Japan. He was one of the first Japanese scholars ...

, mostly based on the Dutch-language ''Ontleedkundige Tafelen'' of 1734, itself a translation of ''Anatomische Tabellen'' (1732) by the German author Johann Adam Kulmus

Johann, typically a male given name, is the German form of ''Iohannes'', which is the Latin form of the Greek name ''Iōánnēs'' (), itself derived from Hebrew name ''Yochanan'' () in turn from its extended form (), meaning "Yahweh is Gracious" ...

.

In 1804,

In 1804, Hanaoka Seishū

was a Japanese surgeon of the Edo period with a knowledge of Chinese herbal medicine, as well as Western surgical techniques he had learned through ''Rangaku'' (literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning"). Hanaoka is said t ...

performed the world's first general anaesthesia

General anaesthesia (UK) or general anesthesia (US) is a medically induced loss of consciousness that renders the patient unarousable even with painful stimuli. This effect is achieved by administering either intravenous or inhalational general ...

during surgery for breast cancer (mastectomy

Mastectomy is the medical term for the surgical removal of one or both breasts, partially or completely. A mastectomy is usually carried out to treat breast cancer. In some cases, women believed to be at high risk of breast cancer have the operat ...

). The surgery involved combining Chinese herbal medicine and Western surgery

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

techniques, 40 years before the better-known Western innovations of Long

Long may refer to:

Measurement

* Long, characteristic of something of great duration

* Long, characteristic of something of great length

* Longitude (abbreviation: long.), a geographic coordinate

* Longa (music), note value in early music mens ...

, Wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

and Morton Morton may refer to:

People

* Morton (surname)

* Morton (given name)

Fictional

* Morton Koopa, Jr., a character and boss in ''Super Mario Bros. 3''

* A character in the ''Charlie and Lola'' franchise

* A character in the 2008 film '' Horton H ...

, with the introduction of diethyl ether

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound in the ether class with the formula , sometimes abbreviated as (see Pseudoelement symbols). It is a colourless, highly volatile, sweet-smelling ("ethereal odour"), extremely flammable liq ...

(1846) and chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, HChlorine, Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to ...

(1847) as general anaesthetics.

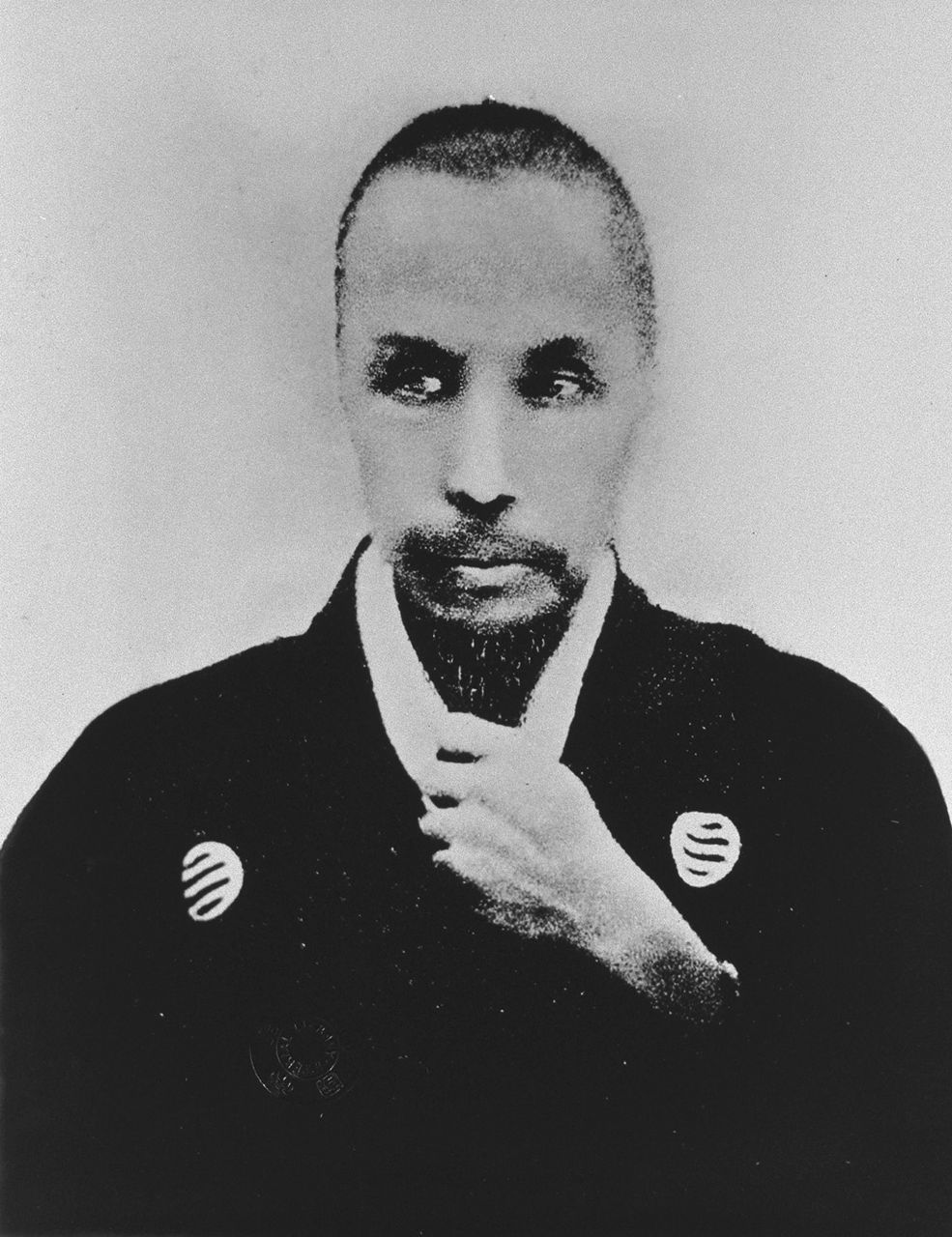

In 1838, the physician and scholar Ogata Kōan

was a Japanese physician and rangaku scholar in late Edo period Japan, noted for establishing an academy which later developed into Osaka University. Many of his students subsequently played important roles in the Meiji Restoration and the weste ...

established the Rangaku school named Tekijuku

Tekijuku (適塾) was a school established in , Osaka, the main trading route between Nagasaki and Edo in 1838 during the Tenpō era of the late Edo period. Its founder was Ogata Kōan, a doctor and scholar of Dutch studies (Rangaku

''Ranga ...

. Famous alumni of the Tekijuku include Fukuzawa Yukichi

was a Japanese educator, philosopher, writer, entrepreneur and samurai who founded Keio University, the newspaper '' Jiji-Shinpō'', and the Institute for Study of Infectious Diseases.

Fukuzawa was an early advocate for reform in Japan. His ...

and Ōtori Keisuke

was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harima Pro ...

, who would become key players in Japan's modernization. He was the author of 1849's , which was the first book on Western pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

to be published in Japan.

Physical sciences

Some of the first scholars of Rangaku were involved with the assimilation of 17th century theories in thephysical science

Physical science is a branch of natural science that studies non-living systems, in contrast to life science. It in turn has many branches, each referred to as a "physical science", together called the "physical sciences".

Definition

Physi ...

s. This is the case of Shizuki Tadao

was a Japanese astronomer and translator of European scientific works into Japanese.

Shizuki was adopted as a child into a family of translators from Dutch to Japanese, and in 1776 Shizuki began working in the family profession; however, in 1777 ...

( :ja:志筑忠雄) an eighth-generation descendant of the Shizuki house of Nagasaki Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

translators, who after having completed for the first time a systematic analysis of Dutch grammar, went on to translate the Dutch edition of ''Introductio ad Veram Physicam'' of the British author John Keil on the theories of Newton (Japanese title: , 1798). Shizuki coined several key scientific terms for the translation, which are still in use in modern Japanese; for example, , (as in electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

), and . A second Rangaku scholar, Hoashi Banri ( :ja:帆足万里), published a manual of physical sciences in 1810 – – based on a combination of thirteen Dutch books, after learning Dutch from just one Dutch-Japanese dictionary.

Electrical sciences

Electrical experiments were widely popular from around 1770. Following the invention of the

Electrical experiments were widely popular from around 1770. Following the invention of the Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typ ...

in 1745, similar electrostatic generator

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electrical generator that produces ''static electricity'', or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back to the earliest ci ...

s were obtained for the first time in Japan from the Dutch around 1770 by Hiraga Gennai

was a Japanese polymath and ''rōnin'' of the Edo period. Gennai was a Pharmacology, pharmacologist, student of ''Rangaku'', physician, author, painter and inventor well known for his ''Elekiter, Erekiteru'' (electrostatic generator), ''Kandan ...

. Static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material or between materials. The charge remains until it is able to move away by means of an electric current or electrical discharge. Static electricity is na ...

was produced by the friction of a glass tube with a gold-plated stick, creating electrical effects. The jars were reproduced and adapted by the Japanese, who called it . As in Europe, these generators were used as curiosities, such as making sparks fly from the head of a subject or for supposed pseudoscientific medical advantages. In ''Sayings of the Dutch'', the ''elekiteru'' is described as a machine that allows one to take sparks out of the human body, to treat sick parts. Elekiterus were sold widely to the public in curiosity shops. Many electric machines derived from the ''elekiteru'' were then invented, particularly by Sakuma Shōzan

sometimes called Sakuma Zōzan, was a Japanese politician and scholar of the Edo period.

Biography

Born Sakuma Kunitada, he was the son of a samurai and scholar and his wife , and a native of (or Shinano Province) in present day's Nagano Pref ...

.

Japan's first electricity manual, by Hashimoto Soukichi ( :ja:橋本宗吉), published in 1811, describes electrical phenomena, such as experiments with electric generators, conductivity through the human body, and the 1750 experiments of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

with lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electric charge, electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the land, ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous ...

.

Chemistry

In 1840, Udagawa Yōan published his , a compilation of scientific books in Dutch, which describes a wide range of scientific knowledge from the West. Most of the Dutch original material appears to be derived from William Henry’s 1799 ''Elements of Experimental Chemistry''. In particular, the book contains a detailed description of the

In 1840, Udagawa Yōan published his , a compilation of scientific books in Dutch, which describes a wide range of scientific knowledge from the West. Most of the Dutch original material appears to be derived from William Henry’s 1799 ''Elements of Experimental Chemistry''. In particular, the book contains a detailed description of the electric battery

An electric battery is a source of electric power consisting of one or more electrochemical cells with external connections for powering electrical devices.

When a battery is supplying power, its positive terminal is the cathode and its negati ...

invented by Volta forty years earlier in 1800. The battery itself was constructed by Udagawa in 1831 and used in experiments, including medical ones, based on a belief that electricity could help cure illnesses.

Udagawa's work reports for the first time in details the findings and theories of Lavoisier in Japan. Accordingly, Udagawa made scientific experiments and created new scientific terms, which are still in current use in modern scientific Japanese, like , , , and .

Optical sciences

Telescopes

Japan's first

Japan's first telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

was offered by the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

captain John Saris

John Saris () was chief merchant on the first English voyage to Japan, which left London in 1611. He stopped at Yemen, missing India (which he had originally intended to visit) and going on to Java, which had the sole permanent English trading sta ...

to Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

in 1614, with the assistance of William Adams, during Saris's mission to open trade between England and Japan. This followed the invention of the telescope by Dutchman Hans Lippershey

Hans Lipperhey (circa 1570 – buried 29 September 1619), also known as Johann Lippershey or Lippershey, was a German- Dutch spectacle-maker. He is commonly associated with the invention of the telescope, because he was the first one who tried to ...

in 1608 by a mere six years. Refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

s were widely used by the populace during the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

, both for pleasure and for the observation of the stars.

After 1640, the Dutch continued to inform the Japanese about the evolution of telescope technology. Until 1676 more than 150 telescopes were brought to Nagasaki. In 1831, after having spent several months in Edo where he could get accustomed with Dutch wares, Kunitomo Ikkansai (a former gun manufacturer) built Japan's first reflecting telescope

A reflecting telescope (also called a reflector) is a telescope that uses a single or a combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century by Isaac Newton as an alternati ...

of the Gregorian type. Kunitomo's telescope had a magnification of 60, and allowed him to make very detailed studies of sun spots and lunar topography. Four of his telescopes remain to this day.

reflecting telescope

A reflecting telescope (also called a reflector) is a telescope that uses a single or a combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century by Isaac Newton as an alternati ...

, 1831.

File:KunitomoMoon1836.jpg, Observation of the moon by Kunitomo in 1836.

Microscopes

Microscopes were invented in the Netherlands during the 17th century, but it is unclear when exactly they reached Japan. Clear descriptions of microscopes are made in the 1720 and in the 1787 book ''Saying of the Dutch''. Although Europeans mainly used microscopes to observe small cellular organisms, the Japanese mainly used them forentomological

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arach ...

purposes, creating detailed descriptions of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s.

Magic lanterns

Magic lanterns, first described in the West by

Magic lanterns, first described in the West by Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works, most notably in the fields of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fe ...

in 1671, became very popular attractions in multiple forms in 18th-century Japan.

The mechanism of a magic lantern, called was described using technical drawings in the book titled in 1779.

Mechanical sciences

Automata

Karakuri Karakuri ( ja, からくり, , mechanism) may refer to:

* ''Karakuri'' (manga), a manga by Masashi Kishimoto

* Karakuri puppet, Japanese 18th/19th century mechanized puppet or automaton

{{disambiguation ...

are mechanized puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or Legendary creature, mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. The puppeteer uses movements of their hands, arms, or control devices such as rods ...

s or automata

An automaton (; plural: automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions.Automaton – Definition and More ...

from Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

from the 18th century to 19th century. The word means "device" and carries the connotations of mechanical devices as well as deceptive ones. Japan adapted and transformed the Western automata, which were fascinating the likes of Descartes, giving him the incentive for his mechanist theories of organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s, and Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

, who loved playing with automatons and miniature wargames

A miniature is a small-scale reproduction, or a small version. It may refer to:

* Portrait miniature, a miniature portrait painting

* Miniature art, miniature painting, engraving and sculpture

* Miniature (chess), a masterful chess game or proble ...

.

Many were developed, mostly for entertainment purposes, ranging from tea-serving to arrow-shooting mechanisms. These ingenious mechanical toys were to become prototypes for the engines of the industrial revolution. They were powered by spring

Spring(s) may refer to:

Common uses

* Spring (season)

Spring, also known as springtime, is one of the four temperate seasons, succeeding winter and preceding summer. There are various technical definitions of spring, but local usage of ...

mechanisms similar to those of clock

A clock or a timepiece is a device used to measure and indicate time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month and the ...

s.

Clocks

Mechanical clocks were introduced into Japan byJesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

or Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

merchants in the sixteenth century. These clocks were of the lantern clock

A lantern clock is a type of antique weight-driven wall clock, shaped like a lantern. They were the first type of clock widely used in private homes. They probably originated before 1500 but only became common after 1600; in Britain around 1620 ...

design, typically made of brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

or iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

, and used the relatively primitive verge and foliot

The verge (or crown wheel) escapement is the earliest known type of mechanical escapement, the mechanism in a mechanical clock that controls its rate by allowing the gear train to advance at regular intervals or 'ticks'. Its origin is unknown. V ...

escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to ...

. These led to the development of an original Japanese clock, called Wadokei

A is a mechanical clock that has been made to tell traditional Japanese time, a system in which daytime and nighttime are always divided into six periods whose lengths consequently change with the season. Mechanical clocks were introduced into ...

.

Neither the pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the ...

nor the balance spring

A balance spring, or hairspring, is a spring attached to the balance wheel in mechanical timepieces. It causes the balance wheel to oscillate with a resonant frequency when the timepiece is running, which controls the speed at which the wheels of ...

were in use among European clocks of the period, and as such they were not included among the technologies available to the Japanese clockmakers at the start of the isolationist period in Japanese history

The first human inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago have been traced to prehistoric times around 30,000 BC. The Jōmon period, named after its cord-marked pottery, was followed by the Yayoi period in the first millennium BC when new inventi ...

, which began in 1641. As the length of an hour changed during winter, Japanese clock makers had to combine two clockworks in one clock. While drawing from European technology they managed to develop more sophisticated clocks, leading to spectacular developments such as the Universal Myriad year clock

The , was a universal clock designed by the Japanese inventor Hisashige Tanaka in 1851. It belongs to the category of Japanese clocks called ''Wadokei''. This clock is designated as an Important Cultural Property and a Mechanical Engineering ...

designed in 1850 by the inventor Tanaka Hisashige

was a Japanese rangaku scholar, engineer and inventor during the Bakumatsu and early Meiji period in Japan. In 1875, he founded what became the Toshiba Corporation. He has been called the "Thomas Edison of Japan" or "Karakuri Giemon."

Biograp ...

, the founder of what would become the Toshiba

, commonly known as Toshiba and stylized as TOSHIBA, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. Its diversified products and services include power, industrial and social infrastructure system ...

corporation.

Pumps

Air pump mechanisms became popular in Europe from around 1660 following the experiments of

Air pump mechanisms became popular in Europe from around 1660 following the experiments of Boyle

Boyle is an English, Irish and Scottish surname of Gaelic, Anglo-Saxon or Norman origin. In the northwest of Ireland it is one of the most common family names. Notable people with the surname include:

Disambiguation

*Adam Boyle (disambiguation), ...

. In Japan, the first description of a vacuum pump

A vacuum pump is a device that draws gas molecules from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The job of a vacuum pump is to generate a relative vacuum within a capacity. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto v ...

appear in Aochi Rinsō Aochi (written: 青地) is a Japanese surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*, Japanese middle-distance runner

*, Japanese ski jumper

*, Japanese samurai

{{surname

Japanese-language surnames ...

( :ja:青地林宗)’s 1825 , and slightly later pressure pumps and void pumps appear in Udagawa Shinsai ( 宇田川榛斎(玄真))’s 1834 . These mechanisms were used to demonstrate the necessity of air for animal life and combustion, typically by putting a lamp or a small dog in a vacuum, and were used to make calculations of pressure and air density.

Many practical applications were found as well, such as in the manufacture of air gun

An air gun or airgun is a gun that fires projectiles pneumatically with compressed air or other gases that are mechanically pressurized ''without'' involving any chemical reactions, in contrast to a firearm, which pressurizes gases ''chemica ...

s by Kunitomo Ikkansai, after he repaired and analyzed the mechanism of some Dutch air guns which had been offered to the ''shōgun'' in Edo. A vast industry of developed, also derived by Kunitomo from the mechanism of air guns, in which oil was continuously supplied through a compressed air mechanism. Kunitomo developed agricultural applications of these technologies, such as a giant pump powered by an ox, to lift irrigation water.

Aerial knowledge and experiments

The first flight of a

The first flight of a hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

by the brothers Montgolfier

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

in France in 1783, was reported less than four years later by the Dutch in Dejima, and published in the 1787 ''Sayings of the Dutch''.

In 1805, almost twenty years later, the Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

Johann Caspar Horner

Johann Caspar Horner (Zürich, 12 March 1774 – Zürich, 3 November 1834) was a Swiss physicist, mathematician and astronomer.

Life

At the beginning he wanted to be a priest, but later he went to Göttingen, where he learnt astronomy. Then he ...

and the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, two scientists of the Kruzenshtern mission that also brought the Russian ambassador Nikolai Rezanov

Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov (russian: Николай Петрович Резанов) ( – ), a Russian nobleman and statesman, promoted the project of Russian colonization of Alaska and California to three successive Emperors of All Russia� ...

to Japan, made a hot air balloon out of Japanese paper (washi

is traditional Japanese paper. The term is used to describe paper that uses local fiber, processed by hand and made in the traditional manner. ''Washi'' is made using fibers from the inner bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (''E ...

) and made a demonstration of the new technology in front of about 30 Japanese delegates.Ivan Federovich Kruzenshtern. "Voyage round the world in the years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806, on orders of his Imperial Majesty Alexander the First, on the vessels Nadezhda and Neva

The Neva (russian: Нева́, ) is a river in northwestern Russia flowing from Lake Ladoga through the western part of Leningrad Oblast (historical region of Ingria) to the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland. Despite its modest length of , it ...

".

Hot air balloons would mainly remain curiosities, becoming the object of experiments and popular depictions, until the development of military usages during the early Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

.

Steam engines

Knowledge of the

Knowledge of the steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

started to spread in Japan during the first half of the 19th century, although the first recorded attempts at manufacturing one date to the efforts of Tanaka Hisashige

was a Japanese rangaku scholar, engineer and inventor during the Bakumatsu and early Meiji period in Japan. In 1875, he founded what became the Toshiba Corporation. He has been called the "Thomas Edison of Japan" or "Karakuri Giemon."

Biograp ...

in 1853, following the demonstration of a steam engine by the Russian embassy of Yevfimiy Putyatin

Yevfimiy Vasilyevich Putyatin (russian: Евфи́мий Васи́льевич Путя́тин; November 8, 1803 – October 16, 1883), also known as was an admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy. His diplomatic mission to Japan r ...

after his arrival in Nagasaki on August 12, 1853.

The Rangaku scholar Kawamoto Kōmin completed a book named in 1845, which was finally published in 1854 as the need to spread Western knowledge became even more obvious with Commodore Perry’s opening of Japan

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government. ...

and the subsequent increased contact with industrial Western nations. The book contains detailed descriptions of steam engines and steamships. Kawamoto had apparently postponed the book's publication due to the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

's prohibition against the building of large ships.

Geography

Modern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints of Matteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima. This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries. With this knowledge,

Modern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints of Matteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima. This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries. With this knowledge, Shibukawa Shunkai

born as Yasui Santetsu (), later called Motoi Santetsu (), was a Japanese scholar, go player and the first official astronomer appointed of the Edo period. He revised the Chinese lunisolar calendar at the shogunate request, drawing up the Jō ...

made the first Japanese globe

A globe is a spherical model of Earth, of some other celestial body, or of the celestial sphere. Globes serve purposes similar to maps, but unlike maps, they do not distort the surface that they portray except to scale it down. A model globe ...

in 1690.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, considerable efforts were made at surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ca ...

and mapping the country, usually with Western techniques and tools. The most famous maps using modern surveying techniques were made by Inō Tadataka

was a Japanese people, Japanese surveying, surveyor and cartographer. He is known for completing the first map of Japan using modern surveying techniques.

Early life

Inō was born in the small village of Ozeki in the middle of Kujūkuri beach, ...

between 1800 and 1818 and used as definitive maps of Japan for nearly a century. They do not significantly differ in accuracy with modern ones, just like contemporary maps of European lands.

Biology

The description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by the Encyclopedists and promoted by von Siebold (a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima). Itō Keisuke created books describing animal species of the Japanese islands, with drawings of a near-photographic quality.

The description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by the Encyclopedists and promoted by von Siebold (a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima). Itō Keisuke created books describing animal species of the Japanese islands, with drawings of a near-photographic quality.

Entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

was extremely popular, and details about insects, often obtained through the use of microscopes ( see above), were widely publicized.

In a rather rare case of "reverse Rangaku" (that is, the science of isolationist Japan making its way to the West), an 1803 treatise on the raising of silk worm

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), cocoons. The be ...

s and manufacture of silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

, the was brought to Europe by von Siebold and translated into French and Italian in 1848, contributing to the development of the silk industry in Europe.

Plants were requested by the Japanese and delivered from the 1640s on, including flowers such as precious tulips and useful items such as the cabbage

Cabbage, comprising several cultivars of ''Brassica oleracea'', is a leafy green, red (purple), or white (pale green) biennial plant grown as an annual vegetable crop for its dense-leaved heads. It is descended from the wild cabbage ( ''B.&nb ...

and the tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

.

Other publications

* Automatons: , 1730. * Mathematics: . * Optics: . * Glass-making: . * Military: , byTakano Chōei

was a prominent scholar of ''Rangaku'' (western science) during the Bakumatsu period in Japan.

Life

Chōei was born as Gotō Kyōsai, the third son of Gotō Sōsuke, a middle-ranking samurai in Mizusawa Domain of Mutsu Province in what is now pa ...

concerning the tactics of the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

, 1850.

* Description of the method of amalgam

Amalgam most commonly refers to:

* Amalgam (chemistry), mercury alloy

* Amalgam (dentistry), material of silver tooth fillings

** Bonded amalgam, used in dentistry

Amalgam may also refer to:

* Amalgam Comics, a publisher

* Amalgam Digital

...

for gold plating

Gold plating is a method of depositing a thin layer of gold onto the surface of another metal, most often copper or silver (to make silver-gilt), by chemical or electrochemical plating. This article covers plating methods used in the modern elec ...

in , or in Shinjitai

are the simplified forms of kanji used in Japan since the promulgation of the Tōyō Kanji List in 1946. Some of the new forms found in ''shinjitai'' are also found in Simplified Chinese characters, but ''shinjitai'' is generally not as extensiv ...

, by Inaba Shin'emon (稲葉新右衛門), 1781.

Aftermath

Commodore Perry

Convention of Kanagawa

The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (, ''Kanagawa Jōyaku'') or the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (, ''Nichibei Washin Jōyaku''), was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March ...

in 1854, he brought technological gifts to the Japanese representatives. Among them was a small telegraph and a small steam train

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the locomot ...

complete with tracks. These were promptly studied by the Japanese as well.

Essentially considering the arrival of Western ships as a threat and a factor for destabilization, the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

ordered several of its fiefs to build warships along Western designs. These ships, such as the Hōō-Maru'', the Shōhei-Maru, and the Asahi-Maru, were designed and built, mainly based on Dutch books and plans. Some were built within a mere year or two of Perry's visit. Similarly, steam engines were immediately studied. Tanaka Hisashige

was a Japanese rangaku scholar, engineer and inventor during the Bakumatsu and early Meiji period in Japan. In 1875, he founded what became the Toshiba Corporation. He has been called the "Thomas Edison of Japan" or "Karakuri Giemon."

Biograp ...

, who had made the Myriad year clock

The , was a universal clock designed by the Japanese inventor Hisashige Tanaka in 1851. It belongs to the category of Japanese clocks called ''Wadokei''. This clock is designated as an Important Cultural Property and a Mechanical Engineering ...

, created Japan's first steam engine, based on Dutch drawings and the observation of a Russian steam ship in Nagasaki in 1853. These developments led to the Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

fief building Japan's first steam ship, the (雲行丸), in 1855, barely two years after Japan's first encounter with such ships in 1853 during Perry's visit.

In 1858, the Dutch officer Kattendijke

Kattendijke is a village in the Dutch province of Zeeland. It is located in the municipality of Goes on the Oosterschelde about 5 km northeast of the city of Goes.

History

The village was first mentioned in 1214 as Cattindic. The etymolo ...

commented:

Last phase of "Dutch" learning

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Netherlands continued to have a key role in transmitting Western know-how to Japan for some time. The Bakufu relied heavily on Dutch expertise to learn about modern Western shipping methods. Thus, the

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Netherlands continued to have a key role in transmitting Western know-how to Japan for some time. The Bakufu relied heavily on Dutch expertise to learn about modern Western shipping methods. Thus, the Nagasaki Naval Training Center

The was a naval training institute, between 1855 when it was established by the government of the Tokugawa shogunate, until 1859, when it was transferred to Tsukiji in Edo.

During the Bakumatsu period, the Japanese government faced increasing ...

was established in 1855 right at the entrance of the Dutch trading post of Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, i ...

, allowing for maximum interaction with Dutch naval knowledge. From 1855 to 1859, education was directed by Dutch naval officers, before the transfer of the school to Tsukiji

Tsukiji (築地) is a district of Chūō, Tokyo, Japan. Literally meaning "reclaimed land", it lies near the Sumida River on land reclaimed from Tokyo Bay in the 18th century during the Edo period. The eponymous Tsukiji fish market opened in 193 ...

in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, where English educators became prominent.

The center was equipped with Japan's first steam warship, the ''Kankō Maru

was a after ''Chōhō (era), Chōhō'' and before ''Chōwa.'' This period spanned the years from July 1004 through December 1012. The reigning emperors were and .

Change of Era

* 1004 : The era name was changed to mark an event or series ...

'', given by the government of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

the same year, which may be one of the last great contributions of the Dutch to Japanese modernization, before Japan opened itself to multiple foreign influences. The future Admiral Enomoto Takeaki

Viscount was a Japanese samurai and admiral of the Tokugawa navy of Bakumatsu period Japan, who remained faithful to the Tokugawa shogunate and fought against the new Meiji government until the end of the Boshin War. He later served in the Mei ...

was one of the students of the Training Center. He was also sent to the Netherlands for five years (1862–1867), with several other students, to develop his knowledge of naval warfare, before coming back to become the admiral of the ''shōgun''s fleet.

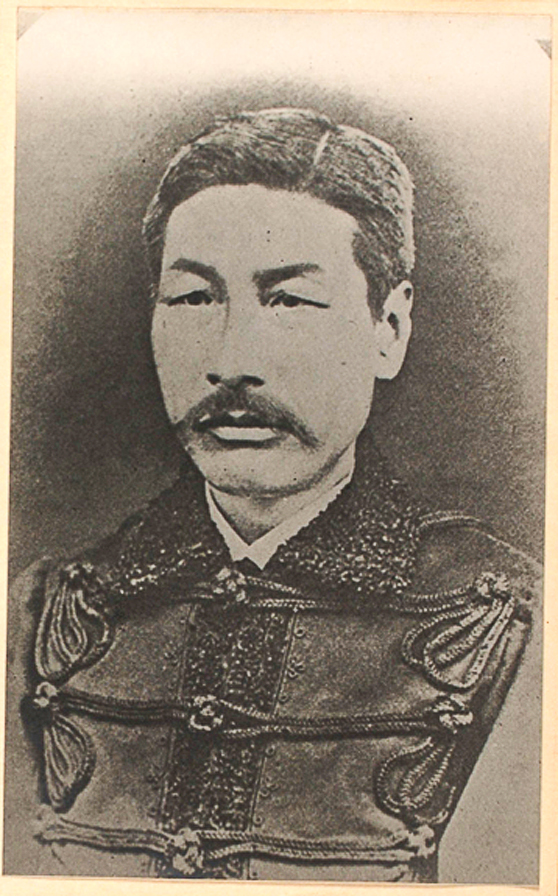

Enduring influence of Rangaku

Scholars of Rangaku continued to play a key role in the modernization of Japan. Scholars such asFukuzawa Yukichi

was a Japanese educator, philosopher, writer, entrepreneur and samurai who founded Keio University, the newspaper '' Jiji-Shinpō'', and the Institute for Study of Infectious Diseases.

Fukuzawa was an early advocate for reform in Japan. His ...

, Ōtori Keisuke

was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harima Pro ...

, Yoshida Shōin

, commonly named , was one of Japan's most distinguished intellectuals in the late years of the Tokugawa shogunate. He devoted himself to nurturing many ''ishin shishi'' who in turn made major contributions to the Meiji Restoration.

Early life ...

, Katsu Kaishū

Count , best known by his nickname , was a Japanese statesman and naval engineer during the late Tokugawa shogunate and early Meiji period. Kaishū was a nickname which he took from a piece of calligraphy (Kaishū Shooku ) by Sakuma Shōzan. He ...

, and Sakamoto Ryōma

was a Japanese ''samurai'', a '' shishi'' and influential figure of the ''Bakumatsu'' and establishment of the Empire of Japan in the late Edo period.

He was a low-ranking ''samurai'' from the Tosa Domain on Shikoku and became an active oppo ...

built on the knowledge acquired during Japan's isolation and then progressively shifted the main language of learning from Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

to English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

.

As these Rangaku scholars usually took a pro-Western stance, which was in line with the policy of the Shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

(Bakufu) but against anti-foreign imperialistic movements, several were assassinated, such as Sakuma Shōzan

sometimes called Sakuma Zōzan, was a Japanese politician and scholar of the Edo period.

Biography

Born Sakuma Kunitada, he was the son of a samurai and scholar and his wife , and a native of (or Shinano Province) in present day's Nagano Pref ...

in 1864 and Sakamoto Ryōma

was a Japanese ''samurai'', a '' shishi'' and influential figure of the ''Bakumatsu'' and establishment of the Empire of Japan in the late Edo period.

He was a low-ranking ''samurai'' from the Tosa Domain on Shikoku and became an active oppo ...

in 1867.

Notable scholars

*

* Arai Hakuseki

was a Confucianist, scholar-bureaucrat, academic, administrator, writer and politician in Japan during the middle of the Edo period, who advised the ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Ienobu. His personal name was Kinmi or Kimiyoshi (君美). Hakuseki (白 ...

(, 1657–1725), author of Sairan Igen and Seiyō Kibun

The is a 3-volume study of the Occident by Japanese politician and scholar Arai Hakuseki based on conversations with Italian missionary Giovanni Battista Sidotti.

The first volume is a collection of conversations with Sidotti. The second volume ...

* Aoki Kon'yō (, 1698–1769)

* Maeno Ryōtaku (, 1723–1803)

* Yoshio Kōgyū (, 1724–1800)

* Ono Ranzan

, also known as , was a Japanese botanist and herbalist, known as the "Japanese Linnaeus".

Ono's real surname was ; his adult given name was . became his art name and his Chinese style courtesy name.

He was born in Kyoto to a courtly family, ...

(, 1729–1810), author of .

* Hiraga Gennai

was a Japanese polymath and ''rōnin'' of the Edo period. Gennai was a Pharmacology, pharmacologist, student of ''Rangaku'', physician, author, painter and inventor well known for his ''Elekiter, Erekiteru'' (electrostatic generator), ''Kandan ...

(, 1729–79) proponent of the "Elekiter

The is the Japanese name for a type of generator of static electricity used for electric experiments in the 18th century. In Japan, Hiraga Gennai presented his own ''elekiter'' in 1776, derived from an ''elekiter'' from Holland. The ''elekiter ...

"

* Gotō Gonzan ()

* Kagawa Shūan ()

* Sugita Genpaku

was a Japanese physician and scholar known for his translation of ''Kaitai Shinsho'' (New Book of Anatomy) and a founder of ''Rangaku'' (Western learning) and ''Ranpō'' (Dutch style medicine) in Japan. He was one of the first Japanese scholars ...

(, 1733–1817) author of .

* Asada Gōryū (, 1734–99)

* Motoki Ryōei (, 1735–94), author of

* Shiba Kōkan

, born Andō Kichirō (安藤吉次郎) or Katsusaburō (勝三郎), was a Japanese painter and printmaker of the Edo period, famous both for his Western-style '' yōga'' paintings, in imitation of Dutch oil painting styles, methods, and themes ...

(, 1747–1818), painter.

* Shizuki Tadao

was a Japanese astronomer and translator of European scientific works into Japanese.

Shizuki was adopted as a child into a family of translators from Dutch to Japanese, and in 1776 Shizuki began working in the family profession; however, in 1777 ...

(, 1760–1806), author of , 1798 and translator of Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer (16 September 16512 November 1716) was a German naturalist, physician, explorer and writer known for his tour of Russia, Persia, India, Southeast Asia, and Japan between 1683 and 1693.

He wrote two books about his travels. ''A ...

's ''Sakokuron''.

* Hanaoka Seishū

was a Japanese surgeon of the Edo period with a knowledge of Chinese herbal medicine, as well as Western surgical techniques he had learned through ''Rangaku'' (literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning"). Hanaoka is said t ...

(, 1760–1835), first physician who performed surgery using general anaesthesia

Anesthesia is a state of controlled, temporary loss of sensation or awareness that is induced for medical or veterinary purposes. It may include some or all of analgesia (relief from or prevention of pain), paralysis (muscle relaxation), a ...

.

* Takahashi Yoshitoki (, 1764–1804)

* Motoki Shōei (, 1767–1822)

* Udagawa Genshin (, 1769–1834), author of .

* Aoji Rinsō (, 1775–1833), author of , 1825.

* Hoashi Banri (, 1778–1852), author of .

* Takahashi Kageyasu (, 1785–1829)

* Matsuoka Joan ()

* Udagawa Yōan (, 1798–1846), author of and

* Itō Keisuke (, 1803–1901), author of

* Takano Chōei

was a prominent scholar of ''Rangaku'' (western science) during the Bakumatsu period in Japan.

Life

Chōei was born as Gotō Kyōsai, the third son of Gotō Sōsuke, a middle-ranking samurai in Mizusawa Domain of Mutsu Province in what is now pa ...

(, 1804–50), physician, dissident, co-translator of a book on the tactics of the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

, , 1850.

* Ōshima Takatō

Ōshima Takatō (大島 高任, May 11, 1826–March 29, 1901) was a Japanese engineer who created the first reverberation blast furnace and first Western-style gun in Japan.

Ōshima was born of samurai status in Morioka City, Nanbu Domain whic ...

(, 1810–71), engineer — established the first western style blast furnace and made the first Western-style cannon in Japan.

* Kawamoto Kōmin (, 1810–71), author of , completed in 1845, published in 1854.

* Ogata Kōan

was a Japanese physician and rangaku scholar in late Edo period Japan, noted for establishing an academy which later developed into Osaka University. Many of his students subsequently played important roles in the Meiji Restoration and the weste ...

(, 1810–63), founder of the Tekijuku

Tekijuku (適塾) was a school established in , Osaka, the main trading route between Nagasaki and Edo in 1838 during the Tenpō era of the late Edo period. Its founder was Ogata Kōan, a doctor and scholar of Dutch studies (Rangaku

''Ranga ...

, and author of , Japan's first treatise on the subject.

* Sakuma Shōzan

sometimes called Sakuma Zōzan, was a Japanese politician and scholar of the Edo period.

Biography

Born Sakuma Kunitada, he was the son of a samurai and scholar and his wife , and a native of (or Shinano Province) in present day's Nagano Pref ...

(, 1811–64)

* Hashimoto Sōkichi ()

* Hazama Shigetomi ()

* Hirose Genkyō (), author of .

* Takeda Ayasaburō

, was a Japanese Rangaku scholar, and the architect of the fortress of Goryōkaku in Hokkaidō.

Takeda was born in the Ōzu Domain (modern-day Ōzu, Ehime) in 1827. He studied medicine, Western sciences (rangaku), navigation, military archite ...

(, 1827–80), architect of the fortress of Goryōkaku

* Ōkuma Shigenobu

Marquess was a Japanese statesman and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy. He served as Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan in 1898 and from 1914 to 1916. Ōkuma was also an early advocate of Western science and culture in Japan, and ...

(, 1838–1922)

* Yoshio Kōgyū (, 1724–1800), translator, collector and scholar

See also

*Dutch missions to Edo

The Dutch East India Company missions to Edo were regular tribute missions to the court of the Tokugawa ''shōgun'' in Edo (modern Tokyo) to reassure the ties between the Bakufu and the ''Opperhoofd''. The ''Opperhoofd'' of the Dutch factory in De ...

* Glossary of Japanese words of Dutch origin

Japanese words of Dutch origin started to develop when the Dutch East India Company initiated trading in Japan from the factory of Hirado in 1609. In 1640, the Dutch were transferred to Dejima, and from then on until 1854 remained the only Wester ...

* Japan–Netherlands relations

Japan–Netherlands relations ( nl, Japans-Nederlandse betrekkingen, ja, 日蘭関係) describes the foreign relations between Japan and the Netherlands. Relations between Japan and the Netherlands date back to 1609, when the first formal trade r ...

* Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

* Nakatsu

* Keio University

, mottoeng = The pen is mightier than the sword

, type = Private research coeducational higher education institution

, established = 1858

, founder = Yukichi Fukuzawa

, endowmen ...

* Uki-e