Rail adhesion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An adhesion railway relies on adhesion traction to move the train. Adhesion traction is the friction between the drive wheels and the steel rail. The term "adhesion railway" is used only when it is necessary to distinguish adhesion railways from railways moved by other means, such as by a stationary engine pulling on a cable attached to the cars or by railways that are moved by a

An adhesion railway relies on adhesion traction to move the train. Adhesion traction is the friction between the drive wheels and the steel rail. The term "adhesion railway" is used only when it is necessary to distinguish adhesion railways from railways moved by other means, such as by a stationary engine pulling on a cable attached to the cars or by railways that are moved by a

Toppling will occur when the overturning moment due to the side force (

Toppling will occur when the overturning moment due to the side force (

The distortion in the wheel and rail is small and localised but the forces which arise from it are large. In addition to the distortion due to the weight, both wheel and rail distort when braking and accelerating forces are applied and when the vehicle is subjected to side forces. These tangential forces cause distortion in the region where they first come into contact, followed by a region of slippage. The net result is that, during traction, the wheel does not advance as far as would be expected from rolling contact but, during braking, it advances further. This mix of elastic distortion and local slipping is known as "creep" (not to be confused with the

The distortion in the wheel and rail is small and localised but the forces which arise from it are large. In addition to the distortion due to the weight, both wheel and rail distort when braking and accelerating forces are applied and when the vehicle is subjected to side forces. These tangential forces cause distortion in the region where they first come into contact, followed by a region of slippage. The net result is that, during traction, the wheel does not advance as far as would be expected from rolling contact but, during braking, it advances further. This mix of elastic distortion and local slipping is known as "creep" (not to be confused with the

An adhesion railway relies on adhesion traction to move the train. Adhesion traction is the friction between the drive wheels and the steel rail. The term "adhesion railway" is used only when it is necessary to distinguish adhesion railways from railways moved by other means, such as by a stationary engine pulling on a cable attached to the cars or by railways that are moved by a

An adhesion railway relies on adhesion traction to move the train. Adhesion traction is the friction between the drive wheels and the steel rail. The term "adhesion railway" is used only when it is necessary to distinguish adhesion railways from railways moved by other means, such as by a stationary engine pulling on a cable attached to the cars or by railways that are moved by a pinion

A pinion is a round gear—usually the smaller of two meshed gears—used in several applications, including drivetrain and rack and pinion systems.

Applications

Drivetrain

Drivetrains usually feature a gear known as the pinion, which may ...

meshing with a rack

Rack or racks may refer to:

Storage and installation

* Amp rack, short for amplifier rack, a piece of furniture in which amplifiers are mounted

* Bicycle rack, a frame for storing bicycles when not in use

* Bustle rack, a type of storage bin ...

.

The friction between the wheels and rails occurs in the wheel-rail interface or contact patch. The traction force, the braking forces and the centering forces, all contribute to stable running. However, running friction increases costs by requiring higher fuel consumption and by increasing the maintenance needed to address fatigue (material) damage, wear

Wear is the damaging, gradual removal or deformation of material at solid surfaces. Causes of wear can be mechanical (e.g., erosion) or chemical (e.g., corrosion). The study of wear and related processes is referred to as tribology.

Wear in ...

on rail heads and on the wheel rims and rail movement from traction and braking forces.

Variation of friction coefficient

Traction orfriction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

is reduced when the top of the rail is wet or frosty or contaminated with grease, oil or decomposing leaves

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, st ...

which compact into a hard slippery lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity a ...

coating. Leaf contamination can be removed by applying " Sandite" (a gel-sand mix) from maintenance trains, using scrubbers and water jets, and can be reduced with long-term management of railside vegetation. Locomotives and streetcars/trams use sand to improve traction when driving wheels start to slip.

Effect of adhesion limits

Adhesion is caused byfriction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

, with maximum tangential force produced by a driving wheel before slipping given by:

:Fmax (N) = coefficient of friction × Weight on wheel (N)

Usually the force needed to start sliding is greater than that needed to continue sliding. The former is concerned with static friction (also known as " stiction") or "limiting friction", whilst the latter is dynamic friction, also called "sliding friction".

For steel on steel, the coefficient of friction can be as high as 0.78, under laboratory conditions, but typically on railways it is between 0.35 and 0.5, whilst under extreme conditions it can fall to as low as 0.05. Thus a 100-tonne locomotive could have a tractive effort of 350 kilonewtons, under the ideal conditions (assuming sufficient force can be produced by the engine), falling to 50 kilonewtons under the worst conditions.

Steam locomotives suffer particularly badly from adhesion issues because the traction force at the wheel rim fluctuates (especially in 2- or most 4-cylinder engines) and, on large locomotives, not all wheels are driven. The "factor of adhesion", being the weight on the driven wheels divided by the theoretical starting tractive effort, was generally designed to be a value of 4 or slightly higher, reflecting a typical wheel-rail friction coefficient of 0.25. A locomotive with a factor of adhesion much lower than 4 would be highly prone to wheelslip, although some 3-cylinder locomotives, such as the SR V Schools class

The SR V class, more commonly known as the ''Schools'' class, is a class of steam locomotive designed by Richard Maunsell for the Southern Railway. The class was a cut down version of his ''Lord Nelson'' class but also incorporated component ...

, operated with a factor of adhesion below 4 because the traction force at the wheel rim do not fluctuate as much. Other factors affecting the likelihood of wheelslip include wheel size and the sensitivity of the regulator/skill of the driver.

All-weather adhesion

The term ''all-weather adhesion'' is usually used inNorth America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, and refers to the adhesion available during traction mode with 99% reliability in all weather conditions.

Toppling conditions

The maximum speed a train can proceed around a turn is limited by the radius of turn, the position of the centre of mass of the units, the wheel gauge and whether the track is ''superelevated'' or ''canted''. Toppling will occur when the overturning moment due to the side force (

Toppling will occur when the overturning moment due to the side force (centrifugal

Centrifugal (a key concept in rotating systems) may refer to:

*Centrifugal casting (industrial), Centrifugal casting (silversmithing), and Spin casting (centrifugal rubber mold casting), forms of centrifigual casting

*Centrifugal clutch

*Centrifu ...

acceleration) is sufficient to cause the inner wheel to begin to lift off the rail. This may result in loss of adhesion – causing the train to slow, preventing toppling. Alternatively, the inertia may be sufficient to cause the train to continue to move at speed causing the vehicle to topple completely.

For a wheel gauge of 1.5 m, no canting, a centre of gravity height of 3 m and speed of 30 m/s (108 km/h), the radius of turn is 360 m. For a modern high-speed train at 80 m/s, the toppling limit would be about 2.5 km. In practice, the minimum radius of turn is much greater than this, as contact between the wheel flanges and rail at high speed could cause significant damage to both. For very high speed, the minimum adhesion limit again appears appropriate, implying a radius of turn of about 13 km. In practice, curved lines used for high speed travel are ''superelevated'' or ''canted'' so that the turn limit is closer to 7 km.

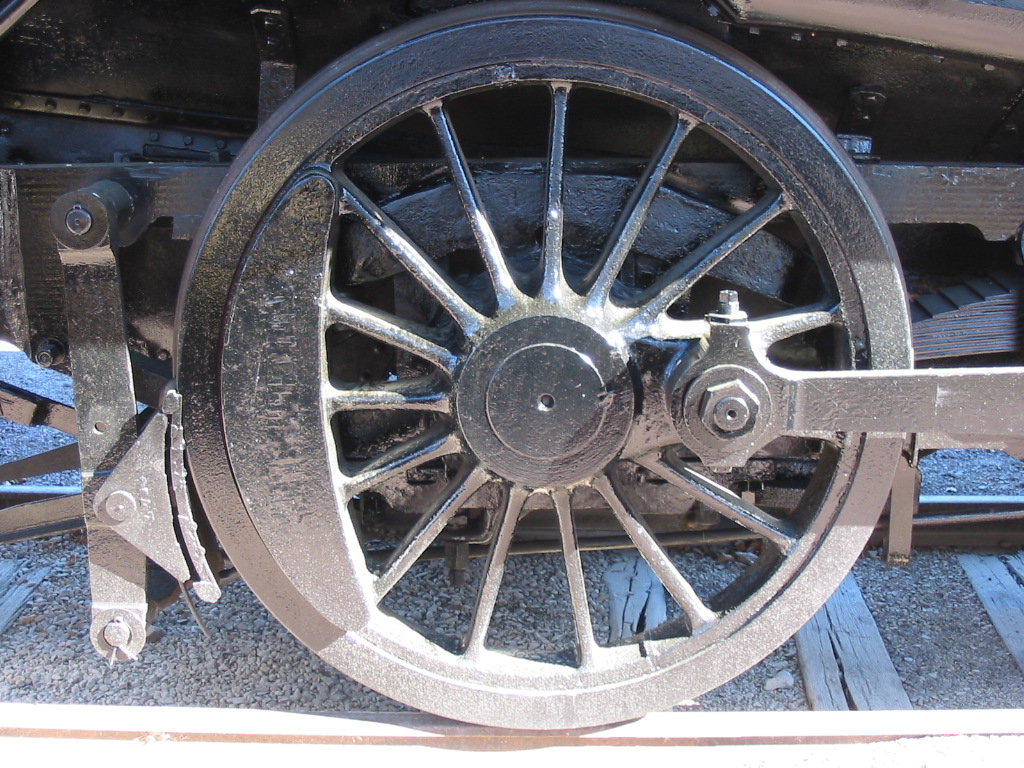

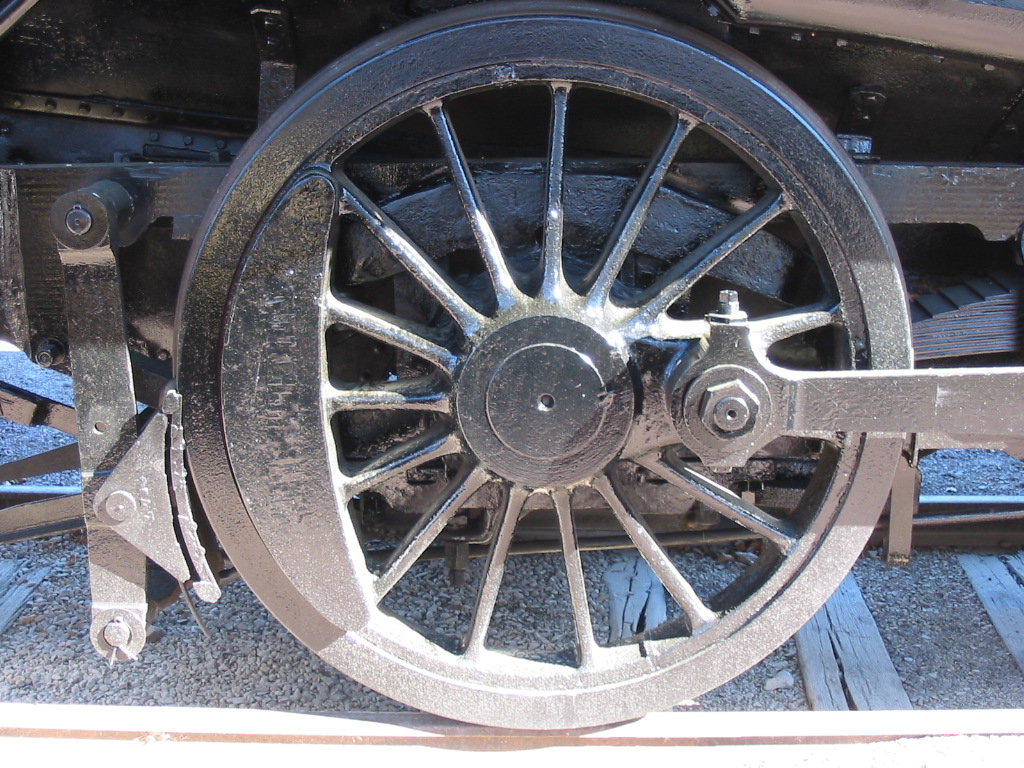

During the 19th century, it was widely believed that coupling the drive wheels would compromise performance and was avoided on engines intended for express passenger service. With a single drive wheelset, the Hertzian contact stress between the wheel and rail necessitated the largest-diameter wheels that could be accommodated. The weight of locomotive was restricted by the stress on the rail, and sandboxes were required, even under reasonable adhesion conditions.

Directional stability and hunting instability

It may be thought that the wheels are kept on the tracks by the flanges. However, close examination of a typical railway wheel reveals that the tread is burnished but the flange is not—the flanges rarely make contact with the rail and, when they do, most of the contact is sliding. The rubbing of a flange on the track dissipates large amounts of energy, mainly as heat but also including noise and, if sustained, would lead to excessive wheel wear. Centering is actually accomplished through shaping of the wheel. The tread of the wheel is slightly tapered. When the train is in the centre of the track, the region of the wheels in contact with the rail traces out a circle which has the same diameter for both wheels. The velocities of the two wheels are equal, so the train moves in a straight line. If, however, the wheelset is displaced to one side, the diameters of the regions of contact, and hence the tangential velocities of the wheels at the running surfaces are different and the wheelset tends to steer back towards the centre. Also, when the train encounters an unbanked turn, the wheelset displaces laterally slightly, so that the outer wheel tread speeds up linearly, and the inner wheel tread slows down, causing the train to turn the corner. Some railway systems employ a flat wheel and track profile, relying oncant

Cant, CANT, canting, or canted may refer to:

Language

* Cant (language), a secret language

* Beurla Reagaird, a language of the Scottish Highland Travellers

* Scottish Cant, a language of the Scottish Lowland Travellers

* Shelta or the Cant, a la ...

alone to reduce or eliminate flange contact.

Understanding how the train stays on the track, it becomes evident why Victorian locomotive engineers were averse to coupling wheelsets. This simple coning action is possible only with wheelsets where each can have some free motion about its vertical axis. If wheelsets are rigidly coupled together, this motion is restricted, so that coupling the wheels would be expected to introduce sliding, resulting in increased rolling losses. This problem was alleviated to a great extent by ensuring the diameter of all coupled wheels was very closely matched.

With perfect rolling contact between the wheel and rail, this coning behaviour manifests itself as a swaying of the train from side to side. In practice, the swaying is damped out below a critical speed, but is amplified by the forward motion of the train above the critical speed. This lateral swaying is known as hunting oscillation. The phenomenon of hunting was known by the end of the 19th century, although the cause was not fully understood until the 1920s and measures to eliminate it were not taken until the late 1960s. The limitation on maximum speed was imposed not by raw power but by encountering an instability in the motion.

The kinematic description of the motion of tapered treads on the two rails is insufficient to describe hunting well enough to predict the critical speed. It is necessary to deal with the forces involved. There are two phenomena which must be taken into account. The first is the inertia of the wheelsets and vehicle bodies, giving rise to forces proportional to acceleration; the second is the distortion of the wheel and track at the point of contact, giving rise to elastic forces. The kinematic approximation corresponds to the case which is dominated by contact forces.

An analysis of the kinematics of the coning action yields an estimate of the wavelength of the lateral oscillation:

::

where ''d'' is the wheel gauge, ''r'' is the nominal wheel radius and ''k'' is the taper of the treads. For a given speed, the longer the wavelength and the lower the inertial forces will be, so the more likely it is that the oscillation will be damped out. Since the wavelength increases with reducing taper, increasing the critical speed requires the taper to be reduced, which implies a large minimum radius of turn.

A more complete analysis, taking account of the actual forces acting, yields the following result for the critical speed of a wheelset:

::

where ''W'' is the axle load for the wheelset, ''a'' is a shape factor related to the amount of wear on the wheel and rail, ''C'' is the moment of inertia of the wheelset perpendicular to the axle, ''m'' is the wheelset mass.

The result is consistent with the kinematic result in that the critical speed depends inversely on the taper. It also implies that the weight of the rotating mass should be minimised compared with the weight of the vehicle. The wheel gauge appears in both the numerator and denominator, implying that it has only a second-order effect on the critical speed.

The true situation is much more complicated, as the response of the vehicle suspension must be taken into account. Restraining springs, opposing the yaw motion of the wheelset, and similar restraints on bogies, may be used to raise the critical speed further. However, in order to achieve the highest speeds without encountering instability, a significant reduction in wheel taper is necessary. For example, taper on Shinkansen

The , colloquially known in English as the bullet train, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan. Initially, it was built to connect distant Japanese regions with Tokyo, the capital, to aid economic growth and development. Beyond l ...

wheel treads was reduced to 1:40 (when the Shinkansen first ran) for both stability at high speeds and performance on curves. That said, from the 1980s onwards, the Shinkansen engineers developed an effective taper of 1:16 by tapering the wheel with multiple arcs, so that the wheel could work effectively both at high speed as well as at sharper curves.

Forces on wheels, creep

The behaviour of vehicles moving on adhesion railways is determined by theforce

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a ...

s arising between two surfaces in contact. This may appear trivially simple from a superficial glance but it becomes extremely complex when studied to the depth necessary to predict useful results.

The first error to address is the assumption that wheels are round. A glance at the tyres of a parked car will immediately show that this is not true: the region in contact with the road is noticeably flattened, so that the wheel and road conform to each other over a region of contact. If this were not the case, the contact stress of a load being transferred through a line contact would be infinite. Rails and railway wheels are much stiffer than pneumatic tyres and tarmac but the same distortion takes place at the region of contact. Typically, the area of contact is elliptical, of the order of 15 mm across.

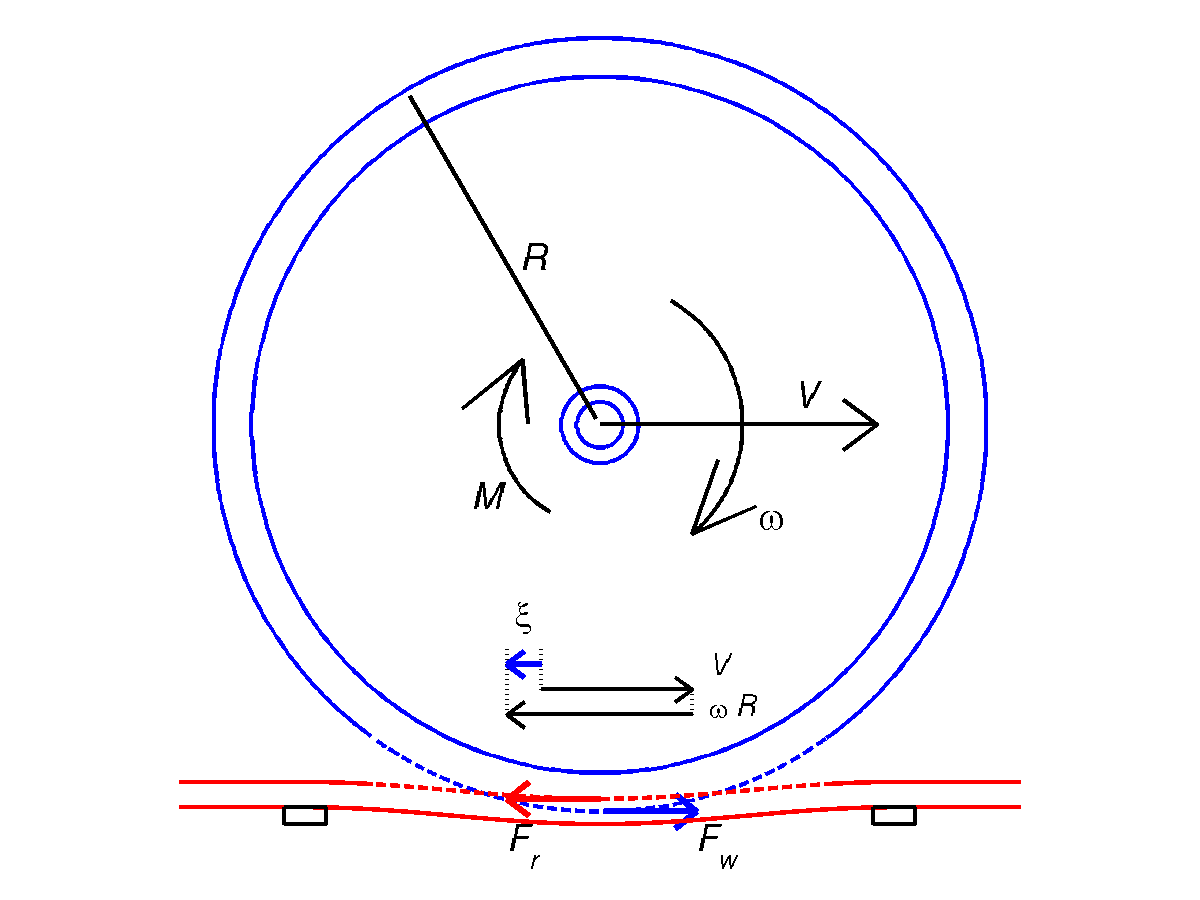

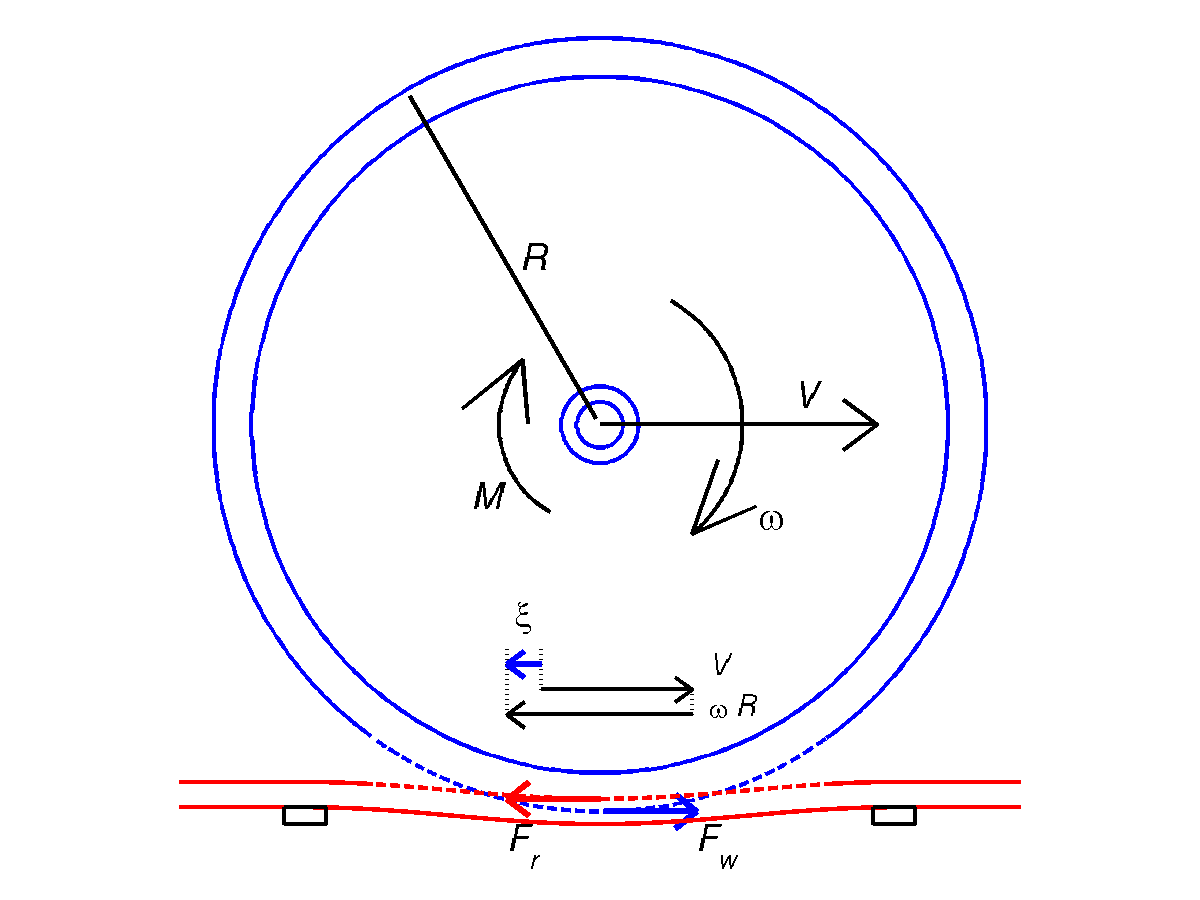

The distortion in the wheel and rail is small and localised but the forces which arise from it are large. In addition to the distortion due to the weight, both wheel and rail distort when braking and accelerating forces are applied and when the vehicle is subjected to side forces. These tangential forces cause distortion in the region where they first come into contact, followed by a region of slippage. The net result is that, during traction, the wheel does not advance as far as would be expected from rolling contact but, during braking, it advances further. This mix of elastic distortion and local slipping is known as "creep" (not to be confused with the

The distortion in the wheel and rail is small and localised but the forces which arise from it are large. In addition to the distortion due to the weight, both wheel and rail distort when braking and accelerating forces are applied and when the vehicle is subjected to side forces. These tangential forces cause distortion in the region where they first come into contact, followed by a region of slippage. The net result is that, during traction, the wheel does not advance as far as would be expected from rolling contact but, during braking, it advances further. This mix of elastic distortion and local slipping is known as "creep" (not to be confused with the creep

Creep, Creeps or CREEP may refer to:

People

* Creep, a creepy person

Politics

* Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), mockingly abbreviated as CREEP, an fundraising organization for Richard Nixon's 1972 re-election campaign

Art ...

of materials under constant load). The definition of creep in this context is:

::

In analysing the dynamics of wheelsets and complete rail vehicles, the contact forces can be treated as linearly dependent on the creep ( Joost Jacques Kalker's linear theory, valid for small creepage) or more advanced theories can be used from frictional contact mechanics.

The forces which result in directional stability, propulsion and braking may all be traced to creep. It is present in a single wheelset and will accommodate the slight kinematic

Kinematics is a subfield of physics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies (groups of objects) without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a fie ...

incompatibility introduced by coupling wheelsets together, without causing gross slippage, as was once feared.

Provided the radius of turn is sufficiently great (as should be expected for express passenger services), two or three linked wheelsets should not present a problem. However, 10 drive wheels (5 main wheelsets) are usually associated with heavy freight locomotives.

Getting the train moving

The adhesion railway relies on a combination of friction and weight to start a train. The heaviest trains require the highest friction and the heaviest locomotive. The friction can vary a great deal, but it was known on early railways that sand helped, and it is still used today, even on locomotives with modern traction controls. To start the heaviest trains, the locomotive must be as heavy as can be tolerated by the bridges along the route and the track itself. The weight of the locomotive must be shared equally by the wheels that are driven, with no weight transfer as the starting force builds. The wheels must turn with a steady driving force on the very small contact area of about 1 cm2 between each wheel and the top of the rail. The top of the rail must be dry, with no man-made or weather-related contamination, such as oil or rain. Friction-enhancing sand or an equivalent is needed. The driving wheels must turn faster than the locomotive is moving (known as creep control) to generate the maximum coefficient of friction, and the axles must be driven independently with their own controller because different axles will see different conditions. The maximum available friction occurs when the wheels are slipping/creeping. If contamination is unavoidable the wheels must be driven with more creep because, although friction is lowered with contamination, the maximum obtainable under those conditions occurs at greater values of creep. The controllers must respond to different friction conditions along the track. Some of the starting requirements were a challenge for steam locomotive designers – "sanding systems that did not work, controls that were inconvenient to operate, lubrication that spewed oil everywhere, drains that wetted the rails, and so on.." Others had to wait for modern electric transmissions on diesel and electric locomotives. The frictional force on the rails and the amount of wheel slip drops steadily as the train picks up speed. A driven wheel does not roll freely but turns faster than the corresponding locomotive velocity. The difference between the two is known as the "slip velocity". "Slip" is the "slip velocity" compared to the "vehicle velocity". When a wheel rolls freely along the rail the contact patch is in what is known as a "stick" condition. If the wheel is driven or braked the proportion of the contact patch with the "stick" condition gets smaller and a gradually increasing proportion is in what is known as a "slip condition". This diminishing "stick" area and increasing "slip" area supports a gradual increase in the traction or braking torque that can be sustained as the force at the wheel rim increases until the whole area is "slip". The "slip" area provides the traction. During the transition from the "all-stick" no-torque to the "all-slip" condition the wheel has had a gradual increase in slip, also known as creep and creepage. High adhesion locomotives control wheel creep to give maximum effort when starting and pulling a heavy train slowly. Slip is the additional speed that the wheel has and creep is the slip level divided by the locomotive speed. These parameters are those that are measured and which go into the creep controller. ::::Sanding

On an adhesion railway, most locomotives will have a sand containment vessel. Properly dried sand can be dropped onto the rail to improve traction under slippery conditions. The sand is most often applied using compressed air via tower, crane, silo or train. When an engine slips, particularly when starting a heavy train, sand applied at the front of the driving wheels greatly aids in tractive effort causing the train to "lift", or to commence the motion intended by the engine driver. Sanding however also has some negative effects. It can cause a "sandfilm", which consists of crushed sand, that is compressed to a film on the track where the wheels make contact. Together with some moisture on the track, which acts as a light adhesive and keeps the applied sand on the track, the wheels "bake" the crushed sand into a more solid layer of sand. Because the sand is applied to the first wheels on the locomotive, the following wheels may run, at least partially and for a limited time, on a layer of sand (sandfilm). While traveling this means that electric locomotives may lose contact to the track-ground, causing the locomotive to createelectromagnetic interference

Electromagnetic interference (EMI), also called radio-frequency interference (RFI) when in the radio frequency spectrum, is a disturbance generated by an external source that affects an electrical circuit by electromagnetic induction, electrost ...

and currents through the couplers. In standstill, when the locomotive is parked, track circuit

A track circuit is an electrical device used to prove the absence of a train on rail tracks to signallers and control relevant signals. An alternative to track circuits are axle counters.

Principles and operation

The basic principle behind ...

s may detect an empty track because the locomotive is electrically isolated from the track.

See also

* Booster engine * Curve resistance *Friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

* Frictional contact mechanics

* Hunting oscillation

* List of steepest gradients on adhesion railways

The inclusion of steep gradients on railways avoids the expensive engineering works required to produce more gentle gradients. However the maximum feasible gradient is limited by how much of a load the locomotive(s) can haul upwards. Braking when ...

* Rail squeal

Rail squeal is a screeching train-track friction sound, commonly occurring on sharp curves.

Squeal is presumably caused by the lateral sticking and slipping of the wheels across top of the railroad track. This results in vibrations in the wheel ...

* Railway tire

The steel wheel of a steam locomotive and other older types of rolling stock were usually fitted with a steel tire (American English) or tyre (in British English, Australian English and others) to provide a replaceable wearing element on a costly ...

* Rolling resistance

Rolling resistance, sometimes called rolling friction or rolling drag, is the force resisting the motion when a body (such as a ball, tire, or wheel) rolls on a surface. It is mainly caused by non-elastic effects; that is, not all the energy ...

* Sandbox (locomotive)

* Slippery rail

Slippery rail, or low railhead adhesion, is a condition of railways (railroads) where contamination of the railhead reduces the traction between the wheel and the rail. This can lead to wheelslip when the train is taking power, and wheelslide ...

* Traction

* Tribology

Tribology is the science and engineering of interacting surfaces in relative motion. It includes the study and application of the principles of friction, lubrication and wear. Tribology is highly interdisciplinary, drawing on many academic fi ...

* Wheelset

* Wheelskate A wheelskate, wheel skate, or axle dolly is a device used to lift the axle of a damaged or blocked rail wheel set and prevent it sliding over the rail. With the axle lifted and wheels off the rails, the train can be moved for repairs.

To be able ...

Footnotes

Sources

* * * * by A H Wickens * {{refend Rail technologies Railways by type