Russian Revolution (1905) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the

Because the Russian economy was tied to European finances, the contraction of Western money markets in 1899–1900 plunged Russian industry into a deep and prolonged crisis; it outlasted the dip in European industrial production. This setback aggravated social unrest during the five years preceding the revolution of 1905.

The government finally recognized these problems, albeit in a shortsighted and narrow-minded way. The Minister of the Interior

Because the Russian economy was tied to European finances, the contraction of Western money markets in 1899–1900 plunged Russian industry into a deep and prolonged crisis; it outlasted the dip in European industrial production. This setback aggravated social unrest during the five years preceding the revolution of 1905.

The government finally recognized these problems, albeit in a shortsighted and narrow-minded way. The Minister of the Interior

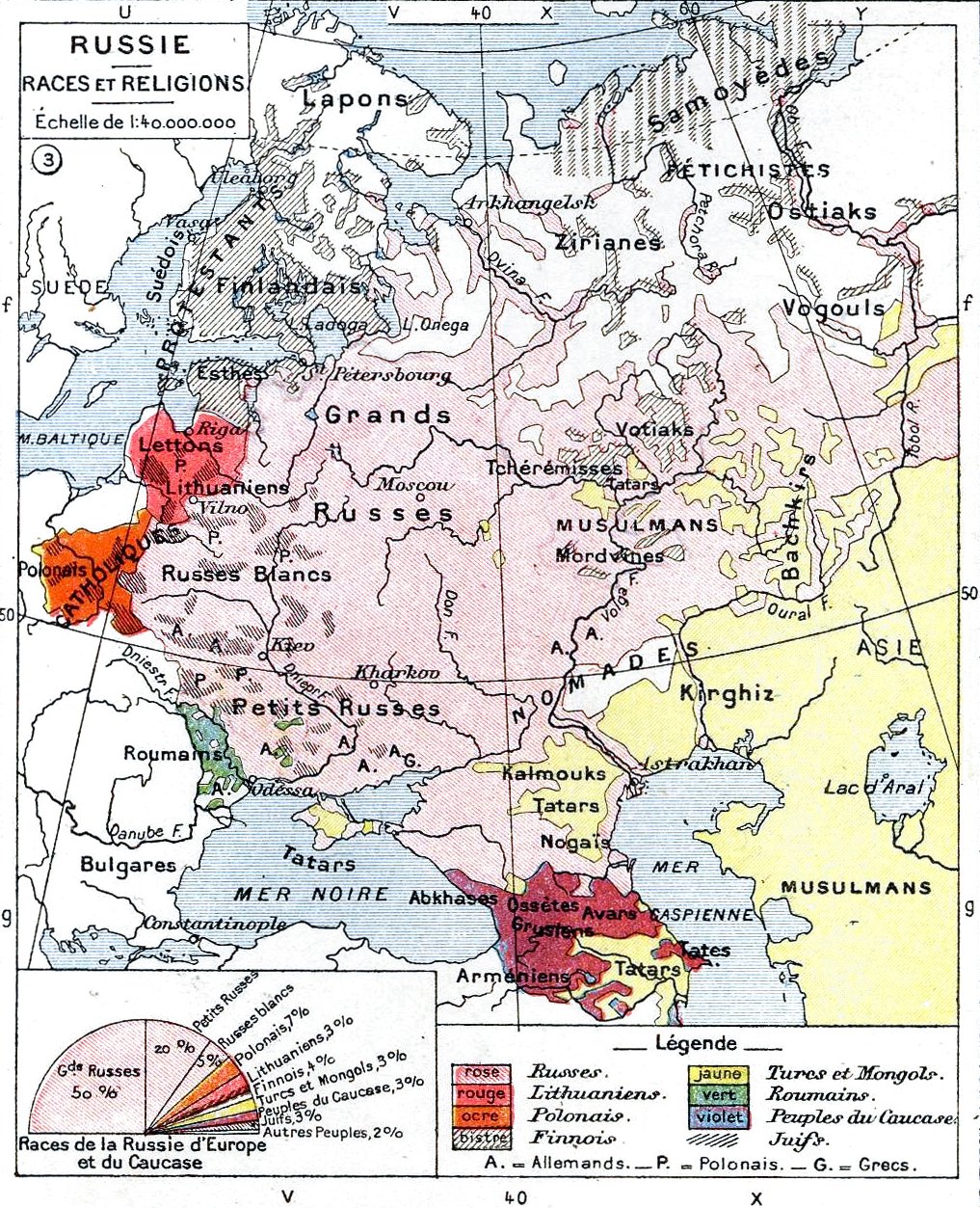

Russia was a multi-ethnic empire. Nineteenth-century Russians saw cultures and religions in a clear hierarchy. Non-Russian cultures were tolerated in the empire but were not necessarily respected.Weeks 2004, 472 Culturally, Europe was favored over Asia, as was

Russia was a multi-ethnic empire. Nineteenth-century Russians saw cultures and religions in a clear hierarchy. Non-Russian cultures were tolerated in the empire but were not necessarily respected.Weeks 2004, 472 Culturally, Europe was favored over Asia, as was

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. The mass unrest was directed against the Tsar, nobility, and ruling class. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

. In response to the public pressure, Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

enacted some constitutional reform (namely the October Manifesto). This took the form of establishing the State Duma, the multi-party system

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in ...

, and the Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 refers to a major revision of the 1832 Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which transformed the formerly absolutist state into one in which the emperor agreed for the first time to share his autocratic powe ...

. Despite popular participation in the Duma, the parliament was unable to issue laws of its own, and frequently came into conflict with Nicholas. Its power was limited and Nicholas continued to hold the ruling authority. Furthermore, he could dissolve the Duma, which he often did.

The 1905 revolution was primarily spurred by the international humiliation as a result of the Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, which ended in the same year. Calls for revolution were intensified by the growing realisation by a variety of sectors of society of the need for reform. Politicians such as Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

had succeeded in partially industrializing Russia but failed to reform and modernize Russia socially. Tsar Nicholas II and the monarchy survived the Revolution of 1905, but its events foreshadowed the 1917 Russian Revolution just twelve years later.

Many historians contend that the 1905 revolution set the stage for the 1917 Russian Revolutions, which saw the monarchy abolished and the Tsar executed. Calls for radicalism were present in the 1905 Revolution, but many of the revolutionaries who were in a position to lead were either in exile or in prison while it took place. The events in 1905 demonstrated the precarious position in which the Tsar found himself. As a result, Tsarist Russia did not undergo sufficient reform, which had a direct impact on the radical politics brewing in the Russian Empire. Although the radicals were still in the minority of the populace, their momentum was growing. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, a revolutionary himself, would later say that the Revolution of 1905 was "The Great Dress Rehearsal", without which the "victory of the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

in 1917 would have been impossible".

Causes

According toSidney Harcave Sidney S. Harcave (September 12, 1916 – October 24, 2008) was an American historian who specialised in Russian history.Mark Kulikowski, 'Sidney S. Harcave, 1916-2008', ''Slavic Review'', Vol. 68, No. 3 (Fall, 2009), p. 742.

He was born in Washin ...

, four problems in Russian society contributed to the revolution. Newly emancipated peasants earned too little and were not allowed to sell or mortgage their allotted land. Ethnic and national minorities resented the government because of its "Russification" of the Empire: it practised discrimination and repression against national minorities, such as banning them from voting; serving in the Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, i ...

or Navy; and limiting their attendance in schools. A nascent industrial working class resented the government for doing too little to protect them, as it banned strikes and organizing into labor unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

. Finally, university students developed a new consciousness, after discipline was relaxed in the institutions, and they were fascinated by increasingly radical ideas, which spread among them.

Also, disaffected soldiers returning from a bloody and disgraceful defeat with Japan, who found inadequate factory pay, shortages, and general disarray, organized in protest.

Taken individually, these issues might not have affected the course of Russian history, but together they created the conditions for a potential revolution.

At the turn of the century, discontent with the Tsar’s dictatorship was manifested not only through the growth of political parties dedicated to the overthrow of the monarchy but also through industrial strikes for betterwage A wage is payment made by an employer to an employee for work done in a specific period of time. Some examples of wage payments include compensatory payments such as ''minimum wage'', '' prevailing wage'', and ''yearly bonuses,'' and remune ...s and working conditions, protests and riots among peasants, university demonstrations, and the assassination of government officials, often done by Socialist Revolutionaries.

Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в (Wenzel (Славик)) из Плевны Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

said in 1903 that, after the agrarian problem, the most serious issues plaguing the country were those of the Jews, the schools, and the workers, in that order.

One of the major contributing factors that changed Russia from a country in unrest to a country in revolt was Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

. Though significant minorities had fomented revolution up to this point, they had been primarily confined to the social elite, while the lower classes had remained aloof from the conflict. However, loyalty of the masses to Tsar Nicholas II was lost on 22 January 1905, when his soldiers fired upon a crowd of protesting workers, led by Georgy Gapon

Georgy Apollonovich Gapon. ( –) was a Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox priest and a popular working-class leader before the 1905 Russian Revolution. After he was discovered to be a police informant, Gapon was murdered by members of the ...

, who were marching to present a petition at the Winter Palace.

Agrarian problem

Every year, thousands of nobles in debt mortgaged their estates to the noble land bank or sold them to municipalities, merchants, or peasants. By the time of the revolution, the nobility had sold off one-third of its land and mortgaged another third. The peasants had been freed by the emancipation reform of 1861, but their lives were generally quite limited. The government hoped to develop the peasants as a politically conservative, land-holding class by enacting laws to enable them to buy land from nobility by paying small installments over many decades.Harcave 1970, 19 Such land, known as "allotment land", would not be owned by individual peasants but by the community of peasants; individual peasants would have rights to strips of land to be assigned to them under theopen field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

. A peasant could not sell or mortgage this land, so in practice he could not renounce his rights to his land, and he would be required to pay his share of redemption dues to the village commune. This plan was intended to prevent peasants from becoming part of the proletariat. However, the peasants were not given enough land to provide for their needs.Harcave 1970, 20

Their earnings were often so small that they could neither buy the food they needed nor keep up the payment of taxes and redemption dues they owed the government for their land allotments. By 1903 their total arrears in payments of taxes and dues was 118 million rubles.The situation worsened as masses of hungry peasants roamed the countryside looking for work and sometimes walked hundreds of

kilometer

The kilometre ( SI symbol: km; or ), spelt kilometer in American English, is a unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), equal to one thousand metres (kilo- being the SI prefix for ). It is now the measurement unit used for ex ...

s to find it. Desperate peasants proved capable of violence. "In the provinces of Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

and Poltava in 1902, thousands of them, ignoring restraints and authority, burst out in a rebellious fury that led to extensive destruction of property and looting of noble homes before troops could be brought to subdue and punish them."

These violent outbreaks caught the attention of the government, so it created many committees to investigate the causes. The committees concluded that no part of the countryside was prosperous; some parts, especially the fertile areas known as the " black-soil region", were in decline.Harcave 1970, 21 Although cultivated acreage had increased in the last half century, the increase had not been proportionate to the growth of the peasant population, which had doubled. "There was general agreement at the turn of the century that Russia faced a grave and intensifying agrarian crisis due mainly to rural overpopulation with an annual excess of fifteen to eighteen live births over deaths per 1,000 inhabitants." The investigations revealed many difficulties but the committees could not find solutions that were both sensible and "acceptable" to the government.

Nationality problem

Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Chur ...

over other religions.

For generations, Russian Jews

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest pop ...

had been considered a special problem. Jews constituted only about 4% of the population, but were concentrated in the western borderlands. Like other minorities in Russia, the Jews lived "miserable and circumscribed lives, forbidden to settle or acquire land outside the cities and towns, legally limited in attendance at secondary school and higher schools, virtually barred from legal professions, denied the right to vote for municipal councilors, and excluded from services in the Navy or the Guards".Harcave 1970, 22

The government's treatment of Jews, although considered a separate issue, was similar to its policies in dealing with all national and religious minorities. Historian Theodore Weeks notes: "Russian administrators, who never succeeded in coming up with a legal definition of 'Pole

Pole may refer to:

Astronomy

*Celestial pole, the projection of the planet Earth's axis of rotation onto the celestial sphere; also applies to the axis of rotation of other planets

*Pole star, a visible star that is approximately aligned with the ...

', despite the decades of restrictions on that ethnic group, regularly spoke of individuals 'of Polish descent' or, alternatively, 'of Russian descent', making identity a function of birth." This policy only succeeded in producing or aggravating feelings of disloyalty. There was growing impatience with their inferior status and resentment against " Russification". Russification is cultural assimilation definable as "a process culminating in the disappearance of a given group as a recognizably distinct element within a larger society".

Besides the imposition of a uniform Russian culture throughout the empire, the government's pursuit of Russification, especially during the second half of the nineteenth century, had political motives. After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, the Russian state was compelled to take into account public opinion, but the government failed to gain the public's support.Weeks 2004, 475 Another motive for Russification policies was the Polish uprising of 1863

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

. Unlike other minority nationalities, the Poles, in the eyes of the Tsar, were a direct threat to the empire's stability. After the rebellion was crushed, the government implemented policies to reduce Polish cultural influences. In the 1870s the government began to distrust German elements on the western border. The Russian government felt that the unification of Germany would upset the power balance among the great powers of Europe and that Germany would use its strength against Russia. The government thought that the borders would be defended better if the borderland were more "Russian" in character. The culmination of cultural diversity created a cumbersome nationality problem that plagued the Russian government in the years leading up to the revolution.

Labour problem

The economic situation in Russia before the revolution presented a grim picture. The government had experimented with ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' capitalist policies, but this strategy largely failed to gain traction within the Russian economy until the 1890s. Meanwhile, "agricultural productivity stagnated, while international prices for grain dropped, and Russia’s foreign debt and need for imports grew. War and military preparations continued to consume government revenues. At the same time, the peasant taxpayers' ability to pay was strained to the utmost, leading to widespread famine in 1891."

In the 1890s, under Finance Minister Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

, a crash governmental program was proposed to promote industrialization. His policies included heavy government expenditures for railroad building and operations, subsidies and supporting services for private industrialists, high protective tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

s for Russian industries (especially heavy industry), an increase in exports, currency stabilization, and encouragement of foreign investments.Skocpol 1979, 91 His plan was successful and during the 1890s "Russian industrial growth averaged 8 percent per year. Railroad mileage grew from a very substantial base by 40 percent between 1892 and 1902." Ironically, Witte's success in implementing this program helped spur the 1905 revolution and eventually the 1917 revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of governm ...

because it exacerbated social tension

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

s. "Besides dangerously concentrating a proletariat, a professional and a rebellious student body in centers of political power, industrialization infuriated both these new forces and the traditional rural classes." The government policy of financing industrialization through taxing peasants forced millions of peasants to work in towns. The "peasant worker" saw his labor in the factory as the means to consolidate his family's economic position in the village and played a role in determining the social consciousness of the urban proletariat. The new concentrations and flows of peasants spread urban ideas to the countryside, breaking down isolation of peasants on communes.

Industrial workers began to feel dissatisfaction with the Tsarist government despite the protective labour laws the government decreed. Some of those laws included the prohibition of children under 12 from working, with the exception of night work in glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling ( quenching ...

factories. Employment of children aged 12 to 15 was prohibited on Sundays and holidays. Workers had to be paid in cash at least once a month, and limits were placed on the size and bases of fines for workers who were tardy. Employers were prohibited from charging workers for the cost of lighting of the shops and plants. Despite these labour protections, the workers believed that the laws were not enough to free them from unfair and inhumane practices. At the start of the 20th century, Russian industrial workers worked on average an 11-hour day (10 hours on Saturday), factory conditions were perceived as grueling and often unsafe, and attempts at independent unions were often not accepted. Many workers were forced to work beyond the maximum of 11 and a half hours per day. Others were still subject to arbitrary and excessive fines for tardiness

Tardiness is the habit of being late or delaying arrival. Being late as a form of misconduct may be formally punishable in various arrangements, such as workplace, school, etc. An opposite personality trait is punctuality.

Workplace tardiness

...

, mistakes in their work, or absence.Harcave 1970, 23 Russian industrial workers were also the lowest-wage workers in Europe. Although the cost of living in Russia was low, "the average worker's 16 ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

s per month could not buy the equal of what the French worker's 110 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

s would buy for him." Furthermore, the same labour laws prohibited organisation of trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s and strikes. Dissatisfaction turned into despair for many impoverished workers, which made them more sympathetic to radical ideas. These discontented, radicalized workers became key to the revolution by participating in illegal strikes and revolutionary protests.

The government responded by arresting labour agitators and enacting more "paternalistic" legislation.Harcave 1970, 24 Introduced in 1900 by Sergei Zubatov, head of the Moscow security department, "police socialism" planned to have workers form workers' societies with police approval to "provide healthful, fraternal activities and opportunities for cooperative self-help together with 'protection' against influences that might have inimical effect on loyalty to job or country". Some of these groups organised in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, Odesa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrati ...

, Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Kyi ...

, Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( uk, Миколаїв, ) is a city and municipality in Southern Ukraine, the administrative center of the Mykolaiv Oblast. Mykolaiv city, which provides Ukraine with access to the Black Sea, is the location of the most downriver brid ...

, and Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.

In 1900–1903, the period of industrial depression caused many firm bankruptcies and a reduction in the employment rate. Employees were restive: they would join legal organisations but turn the organisations toward an end that the organisations' sponsors did not intend. Workers used legitimate means to organise strikes or to draw support for striking workers outside these groups. A strike that began in 1902 by workers in the railroad shops in

The Minister of the Interior, Plehve, designated schools as a pressing problem for the government, but he did not realize it was only a symptom of antigovernment feelings among the educated class. Students of universities, other schools of higher learning, and occasionally of secondary schools and theological seminaries were part of this group.

Student radicalism began around the time

The Minister of the Interior, Plehve, designated schools as a pressing problem for the government, but he did not realize it was only a symptom of antigovernment feelings among the educated class. Students of universities, other schools of higher learning, and occasionally of secondary schools and theological seminaries were part of this group.

Student radicalism began around the time

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the  With the unsuccessful and bloody

With the unsuccessful and bloody  Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their own culture. Kevin O'Connor, ''The History of the Baltic States'', Greenwood Press,

Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their own culture. Kevin O'Connor, ''The History of the Baltic States'', Greenwood Press,

Google Print, p. 58

/ref> Muslim groups were also active, founding the

The October Manifesto, written by

The October Manifesto, written by  Some of the November uprising of 1905 in

Some of the November uprising of 1905 in

Following the Revolution of 1905, the Tsar made last attempts to save his regime, and offered reforms similar to most rulers when pressured by a revolutionary movement. The military remained loyal throughout the Revolution of 1905, as shown by their shooting of revolutionaries when ordered by the Tsar, making overthrow difficult. These reforms were outlined in a precursor to the Constitution of 1906 known as the October Manifesto which created the Imperial Duma. The

Following the Revolution of 1905, the Tsar made last attempts to save his regime, and offered reforms similar to most rulers when pressured by a revolutionary movement. The military remained loyal throughout the Revolution of 1905, as shown by their shooting of revolutionaries when ordered by the Tsar, making overthrow difficult. These reforms were outlined in a precursor to the Constitution of 1906 known as the October Manifesto which created the Imperial Duma. The

The 1905–1907 revolution was at the time the largest wave of strikes and widest emancipatory movement Poland had ever seen, and it would remain so until the 1970s and 1980s. In 1905, 93.2% of Congress Poland's industrial workers went on strike. The first phase of the revolution consisted primarily of mass strikes, rallies, demonstrations—later this evolved into street skirmishes with the police and army as well as bomb assassinations and robberies of transports carrying money to tsarist financial institutions.Rewolucja 1905-07 Na Ziemiach Polskich

The 1905–1907 revolution was at the time the largest wave of strikes and widest emancipatory movement Poland had ever seen, and it would remain so until the 1970s and 1980s. In 1905, 93.2% of Congress Poland's industrial workers went on strike. The first phase of the revolution consisted primarily of mass strikes, rallies, demonstrations—later this evolved into street skirmishes with the police and army as well as bomb assassinations and robberies of transports carrying money to tsarist financial institutions.Rewolucja 1905-07 Na Ziemiach Polskich

Encyklopedia Interia, retrieved on 8 April 2008 One of the major events of that period was the insurrection in Łódź in June 1905, but unrest happened in many other areas too.

Following the shooting of demonstrators in St. Petersburg, a wide-scale general strike began in Riga. On , Russian army troops opened fire on demonstrators killing 73 and injuring 200 people. During the middle of 1905, the focus of revolutionary events moved to the countryside with mass meetings and demonstrations. 470 new parish administrative bodies were elected in 94% of the parishes in Latvia. The Congress of Parish Representatives was held in Riga in November. In autumn 1905, armed conflict between the

Following the shooting of demonstrators in St. Petersburg, a wide-scale general strike began in Riga. On , Russian army troops opened fire on demonstrators killing 73 and injuring 200 people. During the middle of 1905, the focus of revolutionary events moved to the countryside with mass meetings and demonstrations. 470 new parish administrative bodies were elected in 94% of the parishes in Latvia. The Congress of Parish Representatives was held in Riga in November. In autumn 1905, armed conflict between the

1905 Russian Revolution Archive

at marxists.org

Russian Chronology 1904–1914, including the Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath

by Rosa Luxemburg, 1906.

by

Russia and reform (1907)

by

1905

An article on the events of 1905 from an anarchist perspective (Anarcho-Syndicalist Review, no. 42/3, Winter 2005)

Estonia during the Russian Revolution of 1905

(in Estonian)

From the collection of th

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Revolution of 1905 in Poland

(in Polish) {{Authority control 1905 in the Russian Empire Conflicts in 1905 1905 in Finland 1900s in Estonia 1905 in Latvia Political history of Finland Political history of Estonia Political history of Latvia 20th-century revolutions Naval battles involving Romania Naval battles involving Russia Revolutions in the Russian Empire Rebellions against the Russian Empire

Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Russia. It is located i ...

and Rostov-on-Don created such a response that by the next summer, 225,000 in various industries in southern Russia and Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

were on strike.Harcave 1970, 25 These were not the first illegal strikes in the country's history but their aims, and the political awareness and support among workers and non-workers, made them more troubling to the government than earlier strikes. The government responded by closing all legal organisations by the end of 1903.

Educated class as a problem

The Minister of the Interior, Plehve, designated schools as a pressing problem for the government, but he did not realize it was only a symptom of antigovernment feelings among the educated class. Students of universities, other schools of higher learning, and occasionally of secondary schools and theological seminaries were part of this group.

Student radicalism began around the time

The Minister of the Interior, Plehve, designated schools as a pressing problem for the government, but he did not realize it was only a symptom of antigovernment feelings among the educated class. Students of universities, other schools of higher learning, and occasionally of secondary schools and theological seminaries were part of this group.

Student radicalism began around the time Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Fin ...

came to power. Alexander abolished serfdom and enacted fundamental reforms in the legal and administrative structure of the Russian empire, which were revolutionary for their time. He lifted many restrictions on universities and abolished obligatory uniforms and military discipline. This ushered in a new freedom in the content and reading lists of academic courses.Morrissey 1998, 22 In turn, that created student subcultures, as youth were willing to live in poverty in order to receive an education. As universities expanded, there was a rapid growth of newspaper

A newspaper is a Periodical literature, periodical publication containing written News, information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as p ...

s, journals, and an organisation of public lectures and professional societies

A professional association (also called a professional body, professional organization, or professional society) usually seeks to further a particular profession, the interests of individuals and organisations engaged in that profession, and th ...

. The 1860s was a time when the emergence of a new public sphere was created in social life and professional groups. This created the idea of their right to have an independent opinion.

The government was alarmed by these communities, and in 1861 tightened restrictions on admission and prohibited student organisations; these restrictions resulted in the first ever student demonstration, held in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, which led to a two-year closure of the university. The consequent conflict with the state was an important factor in the chronic student protests over subsequent decades. The atmosphere of the early 1860s gave rise to political engagement by students outside universities that became a tenet of student radicalism by the 1870s. Student radicals described "the special duty and mission of the student as such to spread the new word of liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

. Students were called upon to extend their freedoms into society, to repay the privilege of learning by serving the people, and to become in Nikolai Ogarev's phrase 'apostles of knowledge'."Morrissey 1998, 23 During the next two decades, universities produced a significant share of Russia's revolutionaries. Prosecution records from the 1860s and 1870s show that more than half of all political offences were committed by students despite being a minute proportion of the population. "The tactics of the left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

students proved to be remarkably effective, far beyond anyone's dreams. Sensing that neither the university administrations nor the government any longer possessed the will or authority to enforce regulations, radicals simply went ahead with their plans to turn the schools into centres of political activity for students and non-students alike."

They took up problems that were unrelated to their "proper employment", and displayed defiance and radicalism by boycotting examinations, rioting, arranging marches in sympathy with strikers and political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s, circulating petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to some offi ...

s, and writing anti-government propaganda.

This disturbed the government, but it believed the cause was lack of training in patriotism and religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

. Therefore, the curriculum was "toughened up" to emphasize classical language

A classical language is any language with an independent literary tradition and a large and ancient body of written literature. Classical languages are typically dead languages, or show a high degree of diglossia, as the spoken varieties of the ...

and mathematics in secondary schools, but defiance continued.Harcave 1970, 26 Expulsion

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona non ...

, exile, and forced military service also did not stop students. "In fact, when the official decision to overhaul the whole educational system was finally made, in 1904, and to that end Vladimir Glazov, head of General Staff Academy, was selected as Minister of Education, the students had grown bolder and more resistant than ever."

Rise of the opposition

The events of 1905 came after progressive andacademic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

agitation for more political democracy and limits to Tsarist rule in Russia, and an increase in strikes by workers against employers for radical economic demands and union recognition, (especially in southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia (russian: Юг России, ''Yug Rossii'') is a colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia generally covering the Southern Federal District and the North Caucasian Feder ...

). Many socialists view this as a period when the rising revolutionary movement was met with rising reactionary movements. As Rosa Luxemburg stated in 1906 in '' The Mass Strike'', when collective strike activity was met with what is perceived as repression from an autocratic state, economic and political demands grew into and reinforced each other.

Russian progressives formed the Union of Zemstvo

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexande ...

Constitutionalists in 1903 and the Union of Liberation

The Union of Liberation (russian: Союз Освобождения, ''Soyuz Osvobozhdeniya'') was a liberal political group founded in Saint Petersburg, Russia in January 1904 under the influence of Peter Berngardovich Struve, a former Marxist. ...

in 1904, which called for a constitutional monarchy. Russian socialists formed two major groups: the Socialist Revolutionary Party (founded in 1902), which followed the Russian populist tradition, and the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (founded in 1898).

In late 1904 liberals started a series of banquets (modeled on the ''campagne des banquets

The Campagne des banquets (''banquet campaign'') were political meetings during the July Monarchy in France which destabilized the King of the French Louis-Philippe (France), Louis-Philippe. The campaign officially took place from 9 July 1847 to 25 ...

'' leading up to the French Revolution of 1848), nominally celebrating the 40th anniversary of the liberal court statutes, but actually an attempt to circumvent laws against political gatherings. The banquets resulted in calls for political reforms and a constitution. In November 1904 a ( ru , Земский съезд)—a gathering of zemstvo delegates representing all levels of Russian society—called for a constitution, civil liberties and a parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. On , the Moscow City Duma

The Moscow City Duma (russian: Московская городская дума, Moskovskaya gorodskaya duma) is the regional parliament ( city duma) of Moscow, a federal subject and the capital city of Russia. As Moscow is one of three fede ...

passed a resolution demanding the establishment of an elected national legislature, full freedom of the press, and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freed ...

. Similar resolutions and appeals from other city dumas and zemstvo councils followed.

Emperor Nicholas II made a move to meet many of these demands, appointing liberal Pyotr Dmitrievich Sviatopolk-Mirsky

Prince Pyotr Dmitrievich Svyatopolk-Mirsky (russian: Пётр Дми́триевич Святопо́лк-Ми́рский, tr. ; , in Vladikavkaz – , in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire) was a Russian general, politician, and police official.

...

as Minister of the Interior after the July 1904 assassination of Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в (Wenzel (Славик)) из Плевны Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

. On , the Emperor issued a manifesto promising the broadening of the zemstvo system and more authority for local municipal councils, insurance for industrial workers, the emancipation of Inorodtsy

In the Russian Empire, inorodtsy (russian: иноро́дцы) (singular: inorodets (russian: инородец), Literally meaning "of different descent/nation", "of foreign (alien) origin") was a special ethnicity-based category of population. In ...

and the abolition of censorship. The crucial demand—that for a representative national legislature—was missing in the manifesto.

Worker strikes in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

broke out in March 1902. Strikes on the railways, originating from pay disputes, took on other issues and drew in other industries, culminating in a general strike at Rostov-on-Don in November 1902.

Daily meetings of 15,000 to 20,000 heard openly revolutionary appeals for the first time, before a massacre defeated the strikes. But reaction to the massacres brought political demands to purely economic ones. Luxemburg described the situation in 1903 by saying: "the whole of South Russia in May, June and July was aflame",

including Baku (where separate wage struggles culminated in a citywide general strike) and Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

, where commercial workers gained a reduction in the working day, and were joined by factory workers. In 1904, massive strike waves broke out in Odessa in the spring, in Kyiv in July, and in Baku in December. This all set the stage for the strikes in St. Petersburg in December 1904 to January 1905 seen as the first step in the 1905 revolution.

Another contributing factor behind the revolution was the Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

massacre of protesters that took place in January 1905 in St. Petersburg sparked a spate of civil unrest in the Russian Empire. Lenin urged Bolsheviks to take a greater role in the events, encouraging violent insurrection. In doing so, he adopted SR slogans regarding "armed insurrection", "mass terror", and "the expropriation of gentry land", resulting in Menshevik accusations that he had deviated from orthodox Marxism. In turn, he insisted that the Bolsheviks split completely with the Mensheviks; many Bolsheviks refused, and both groups attended the Third RSDLP Congress

The 3rd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was held during 25 April - 10 May Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="12–27_April_Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S.)1905_in_ O.S.)">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;" ...

, held in London in April 1905 at the Brotherhood Church

The Brotherhood Church is a Christian anarchist and pacifist community. An intentional community with Quaker origins has been located at Stapleton, near Pontefract, Yorkshire, since 1921.

History

The church can be traced back to 1887 when a ...

. Lenin presented many of his ideas in the pamphlet ''Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution

''Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution'' is one of the most important of Lenin's early writings.

Background

It was written in June and July 1905, while the Russian Revolution of 1905 was taking place.

Content

Lenin's ...

'', published in August 1905. Here, he predicted that Russia's liberal bourgeoisie would be sated by a transition to constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

and thus betray the revolution; instead he argued that the proletariat would have to build an alliance with the peasantry to overthrow the Tsarist regime and establish the "provisional revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry."

Start of the revolution

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putilov plant

The Kirov Plant, Kirov Factory or Leningrad Kirov Plant (LKZ) ( rus, Кировский завод, Kirovskiy zavod) is a major Russian mechanical engineering and agricultural machinery manufacturing plant in St. Petersburg, Russia. It was esta ...

(a railway and artillery supplier) in St. Petersburg. Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers to 150,000 workers in 382 factories. By , the city had no electricity and newspaper distribution was halted. All public areas were declared closed.

Controversial Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon

Georgy Apollonovich Gapon. ( –) was a Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox priest and a popular working-class leader before the 1905 Russian Revolution. After he was discovered to be a police informant, Gapon was murdered by members of the ...

, who headed a police-sponsored workers' association, led a huge workers' procession to the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

to deliver a petition to the Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

on Sunday, . The troops guarding the Palace were ordered to tell the demonstrators not to pass a certain point, according to Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

, and at some point, troops opened fire on the demonstrators, causing between 200 (according to Witte) and 1,000 deaths. The event became known as Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

, and is considered by many scholars as the start of the active phase of the revolution.

The events in St. Petersburg provoked public indignation and a series of massive strikes that spread quickly throughout the industrial centers of the Russian Empire. Polish socialists—both the PPS and the SDKPiL

The Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania ( pl, Socjaldemokracja Królestwa Polskiego i Litwy, SDKPiL), , LKLSD), originally the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland (SDKP), was a Marxist political party founded in 1893 an ...

—called for a general strike. By the end of January 1905, over 400,000 workers in Russian Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

were on strike (see Revolution in the Kingdom of Poland (1905–1907)). Half of European Russia's industrial workers went on strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland.Robert Blobaum, ''Feliks Dzierzynski and the SDKPiL: A Study of the Origins of Polish Communism'', p. 123 There were also strikes in Finland and the Baltic coast. In Riga, 130 protesters were killed on , and in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

a few days later over 100 strikers were shot on the streets. By February, there were strikes in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

, and by April, in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

and beyond. In March, all higher academic institutions were forcibly closed for the remainder of the year, adding radical students to the striking workers. A strike by railway workers on quickly developed into a general strike in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. This prompted the setting up of the short-lived Saint Petersburg Soviet

The Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates (later the Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Deputies) was a workers' council, or soviet, in Saint Petersburg in 1905.

Origins

The Soviet had its origins in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, when Nicholas II ...

of Workers' Delegates, an admixture of Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

headed by Khrustalev-Nossar and despite the Iskra

''Iskra'' ( rus, Искра, , ''the Spark'') was a political newspaper of Russian socialist emigrants established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

History

Due to political repression under Tsar Nicho ...

split would see the likes of Julius Martov and Georgi Plekhanov spar with Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

. Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, who felt a strong connection to the Bolsheviki, had not given up a compromise but spearheaded strike action in over 200 factories. By , over 2 million workers were on strike and there were almost no active railways in all of Russia. Growing inter-ethnic confrontation throughout the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

resulted in Armenian–Tatar massacres, heavily damaging the cities and the Baku oilfield

A petroleum reservoir or oil and gas reservoir is a subsurface accumulation of hydrocarbons contained in porous or fractured rock formations.

Such reservoirs form when kerogen (ancient plant matter) is created in surrounding rock by the presence ...

s.

With the unsuccessful and bloody

With the unsuccessful and bloody Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

(1904–1905) there was unrest in army reserve units. On 2 January 1905, Port Arthur was lost; in February 1905, the Russian army was defeated at Mukden

Shenyang (, ; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly known as Fengtian () or by its Manchu name Mukden, is a major Chinese sub-provincial city and the provincial capital of Liaoning province. Located in central-north Liaoning, it is the prov ...

, losing almost 80,000 men. On 27–28 May 1905, the Russian Baltic Fleet was defeated at Tsushima. Witte was dispatched to make peace, negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

(signed ). In 1905, there were naval mutinies at Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

(see Sevastopol Uprising

Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt (russian: Пётр Петрович Шмидт; – ) was one of the leaders of the Sevastopol Uprising during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Early years

Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt was born in 1867 in Odessa, Russian ...

), Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

, and Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, peaking in June with the mutiny aboard the battleship ''Potemkin''. The mutineers eventually surrendered the battleship to Romanian authorities on 8 July in exchange for asylum, then the Romanians returned her to Imperial Russian authorities on the following day. Some sources claim over 2,000 sailors died in the suppression. The mutinies were disorganised and quickly crushed. Despite these mutinies, the armed forces were largely apolitical and remained mostly loyal, if dissatisfied—and were widely used by the government to control the 1905 unrest.

Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their own culture. Kevin O'Connor, ''The History of the Baltic States'', Greenwood Press,

Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their own culture. Kevin O'Connor, ''The History of the Baltic States'', Greenwood Press, Google Print, p. 58

/ref> Muslim groups were also active, founding the

Union of the Muslims of Russia

The Union of the Muslims of Russia (Ittifaq, short for tt-Cyrl, Иттифак әл-мөслимин, ''Ittifaq âl-Möslimin'' and , ''Ittifaq al-Muslimin'') was a political organisation and party of Muslims in the late Russian Empire. The organi ...

in August 1905. Certain groups took the opportunity to settle differences with each other rather than the government. Some nationalists undertook anti-Jewish

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s, possibly with government aid, and in total over 3,000 Jews were killed.Taylor, BD (2003). ''Politics and the Russian Army: Civil-Military Relations, 1689–2000''. Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

. p. 69.

The number of prisoners throughout the Russian Empire, which had peaked at 116,376 in 1893, fell by over a third to a record low of 75,009 in January 1905, chiefly because of several mass amnesties granted by the Tsar;Wheatcroft, SG (2002). ''Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History''. Palgrave Macmillan

Palgrave Macmillan is a British academic and trade publishing company headquartered in the London Borough of Camden. Its programme includes textbooks, journals, monographs, professional and reference works in print and online. It maintains off ...

. ''The Pre-Revolutionary Period'', p. 34. the historian S G Wheatcroft has wondered what role these released criminals played in the 1905–06 social unrest.

Government response

On 12 January 1905, the Tsar appointedDmitri Feodorovich Trepov

Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov (transliterated at the time as Trepoff) (15 December 1850 – 15 September 1906) was Head of the Moscow police, Governor-General of St. Petersburg with extraordinary powers, and Assistant Interior Minister with full contr ...

as governor in St Petersburg and dismissed the Minister of the Interior, Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirskii, on . He appointed a government commission "to enquire without delay into the causes of discontent among the workers in the city of St Petersburg and its suburbs" in view of the strike movement. The commission was headed by Senator NV Shidlovsky, a member of the State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

, and included officials, chiefs of government factories, and private factory owners. It was also meant to have included workers' delegates elected according to a two-stage system. Elections of the workers delegates were, however, blocked by the socialists who wanted to divert the workers from the elections to the armed struggle. On , the commission was dissolved without having started work. Following the assassination of his uncle, the Grand Duke Sergei Aleksandrovich, on , the Tsar made new concessions. On he published the '' Bulygin Rescript'', which promised the formation of a consultative assembly, religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

, freedom of speech (in the form of language rights

Linguistic rights are the human and civil rights concerning the individual and collective right to choose the language or languages for communication in a private or public atmosphere. Other parameters for analyzing linguistic rights include the ...

for the Polish minority) and a reduction in the peasants' redemption payments. On , about 300 Zemstvo and municipal representatives held three meetings in Moscow, which passed a resolution, asking for popular representation at the national level. On , Nicholas II had received a Zemstvo deputation. Responding to speeches by Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy

Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy (russian: Серге́й Никола́евич Трубецко́й; 4 August Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._23_June.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O._S._23_June">O ...

and Mr Fyodrov, the Tsar confirmed his promise to convene an assembly of people's representatives.

Height of the Revolution

Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

agreed on to the creation of a State Duma of the Russian Empire

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four time ...

but with consultative powers only. When its slight powers and limits on the electorate were revealed, unrest redoubled. The Saint Petersburg Soviet

The Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates (later the Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Deputies) was a workers' council, or soviet, in Saint Petersburg in 1905.

Origins

The Soviet had its origins in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, when Nicholas II ...

was formed and called for a general strike in October, refusal to pay taxes, and the en masse withdrawal of bank deposits.

In June and July 1905, there were many peasant uprisings in which peasants seized land and tools.Paul Barnes, R. Paul Evans, Peris Jones-Evans (2003). ''GCSE History for WJEC Specification A''. Heinemann. p. 68 Disturbances in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland culminated in June 1905 in the Łódź insurrection. Surprisingly, only one landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, t ...

was recorded as killed. Far more violence was inflicted on peasants outside the commune: 50 deaths were recorded. Anti-tsarist protests displaced onto Jewish communities in the October 1905 Kishinev pogrom.

The October Manifesto, written by

The October Manifesto, written by Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

and Alexis Obolenskii, was presented to the Tsar on . It closely followed the demands of the Zemstvo Congress in September, granting basic civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

, allowing the formation of political parties, extending the franchise towards universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

, and establishing the Duma as the central legislative body.

The Tsar waited and argued for three days, but finally signed the manifesto on , citing his desire to avoid a massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

and his realisation that there was insufficient military force available to pursue alternative options. He regretted signing the document, saying that he felt "sick with shame at this betrayal of the dynasty ... the betrayal was complete".

When the manifesto was proclaimed, there were spontaneous demonstrations of support in all the major cities. The strikes in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and elsewhere officially ended or quickly collapsed. A political amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

was also offered. The concessions came hand-in-hand with renewed, and brutal, action against the unrest. There was also a backlash from the conservative elements of society, with right-wing attacks on strikers, left-wingers, and Jews.

While the Russian liberals were satisfied by the October Manifesto and prepared for upcoming Duma elections, radical socialists and revolutionaries denounced the elections and called for an armed uprising to destroy the Empire.

Some of the November uprising of 1905 in

Some of the November uprising of 1905 in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, headed by retired naval Lieutenant Pyotr Schmidt

Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt (russian: Пётр Петрович Шмидт; – ) was one of the leaders of the Sevastopol Uprising during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Early years

Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt was born in 1867 in Odessa, Russian E ...

, was directed against the government, while some was undirected. It included terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

, worker strikes, peasant unrest and military mutinies

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

, and was only suppressed after a fierce battle. The Trans-Baikal railroad fell into the hands of striker committees and demobilised soldiers returning from Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

after the Russo–Japanese War. The Tsar had to send a special detachment of loyal troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

to restore order.

Between , there was a general strike by Russian workers. The government sent troops on 7 December, and a bitter street-by-street fight began. A week later, the Semyonovsky Regiment

The Semyonovsky Lifeguard Regiment (, ) was one of the two oldest guard regiments of the Imperial Russian Army. The other one was the Preobrazhensky Regiment. In 2013, it was recreated for the Russian Armed Forces as a rifle regiment, its na ...

was deployed, and used artillery to break up demonstrations and to shell workers' districts. On , with around a thousand people dead and parts of the city in ruins, the workers surrendered. After a final spasm in Moscow, the uprisings ended in December 1905. According to figures presented in the Duma by Professor Maksim Kovalevsky

Maksim Maksimovich Kovalevsky (Russian: Максим Максимович Ковалевский; 8 September 1851 – 5 April 1916) was a Russian jurist and the main authority on sociology in the Russian Empire. He was vice-president (1895) and p ...

, by April 1906, more than 14,000 people had been executed and 75,000 imprisoned. Historian Brian Taylor states the number of deaths in the 1905 Revolution was in the "thousands", and notes one source that puts the figure at over 13,000 deaths.

Results

Following the Revolution of 1905, the Tsar made last attempts to save his regime, and offered reforms similar to most rulers when pressured by a revolutionary movement. The military remained loyal throughout the Revolution of 1905, as shown by their shooting of revolutionaries when ordered by the Tsar, making overthrow difficult. These reforms were outlined in a precursor to the Constitution of 1906 known as the October Manifesto which created the Imperial Duma. The

Following the Revolution of 1905, the Tsar made last attempts to save his regime, and offered reforms similar to most rulers when pressured by a revolutionary movement. The military remained loyal throughout the Revolution of 1905, as shown by their shooting of revolutionaries when ordered by the Tsar, making overthrow difficult. These reforms were outlined in a precursor to the Constitution of 1906 known as the October Manifesto which created the Imperial Duma. The Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 refers to a major revision of the 1832 Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which transformed the formerly absolutist state into one in which the emperor agreed for the first time to share his autocratic powe ...

, also known as the Fundamental Laws, set up a multiparty system and a limited constitutional monarchy. The revolutionaries were quelled and satisfied with the reforms, but it was not enough to prevent the 1917 revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of governm ...

that would later topple the Tsar's regime.

Creation of Duma and appointment of Stolypin

There had been earlier attempts in establishing a Russian Duma before the October Manifesto, but these attempts faced dogged resistance. One attempt in July 1905, called the Bulygin Duma, tried to reduce the assembly into a consultative body. It also proposed limiting voting rights to those with a higher property qualification, excluding industrial workers. Both sides—the opposition and the conservatives—were not pleased with the results. Another attempt in August 1905 was almost successful, but that too died when Nicholas insisted on the Duma's functions be relegated to an advisory position. The October Manifesto, aside from granting the population the freedom of speech and assembly, proclaimed that no law would be passed without examination and approval by the Imperial Duma. The Manifesto also extended the suffrage to universal proportions, allowing for greater participation in the Duma, though the electoral law in 11 December still excluded women.Nader Sohrabi, Historicizing Revolutions, p. 1425 Nevertheless, the tsar retained the power of veto. Propositions for restrictions to the Duma's legislative powers remained persistent. A decree on 20 February 1906 transformed theState Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

, the advisory body, into a second chamber with legislative powers "equal to those of the Duma". Not only did this transformation violate the Manifesto, but the Council became a buffer zone between the tsar and Duma, slowing whatever progress the latter could achieve. Even three days before the Duma's first session, on 24 April 1906, the Fundamental Laws further limited the assembly's movement by giving the tsar the sole power to appoint/dismiss ministers. Adding insult was the indication that the Tsar alone had control over many facets of political reins—all without the Duma's expressed permission. The trap seemed perfectly set for the unsuspecting Duma: by the time the assembly convened in 27 April, it quickly found itself unable to do much without violating the Fundamental Laws. Defeated and frustrated, the majority of the assembly voted no confidence and handed in their resignations after a few weeks on 13 May.Nader Sohrabi, Historicizing Revolutions, p. 1427

The attacks on the Duma were not confined to its legislative powers. By the time the Duma opened, it was missing crucial support from its populace, thanks in no small part to the government's return to Pre-Manifesto levels of suppression. The Soviets were forced to lay low for a long time, while the zemstvos turned against the Duma when the issue of land appropriation came up. The issue of land appropriation was the most contentious of the Duma's appeals. The Duma proposed that the government distribute its treasury, "monastic and imperial lands", and seize private estates as well. The Duma, in fact, was preparing to alienate some of its more affluent supporters, a decision that left the assembly without the necessary political power to be efficient.

Nicholas II remained wary of having to share power with reform-minded bureaucrats. When the pendulum in 1906 elections swung to the left, Nicholas immediately ordered the Duma's dissolution just after 73 days. Hoping to further squeeze the life out of the assembly, he appointed a tougher prime minister in Petr Stolypin as the liberal Witte's replacement. Much to Nicholas's chagrin, Stolypin attempted to bring about acts of reform (land reform), while retaining measures favorable to the regime (stepping up the number of executions of revolutionaries). After the revolution subsided, he was able to bring economic growth back to Russia's industries, a period which lasted until 1914. But Stolypin's efforts did nothing to prevent the collapse of the monarchy, nor seemed to satisfy the conservatives. Stolypin died from a bullet wound by a revolutionary, Dmitry Bogrov

Dmitry Grigoriyevich Bogrov ( – ) () was the assassin of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.

On Bogrow was sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on in the Kiev fortress Lyssa Hora.

Stolypin's widow had campaigned in vain to spare the ass ...

, on 5 September 1911.

October Manifesto