Russian Annexation Of Georgia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

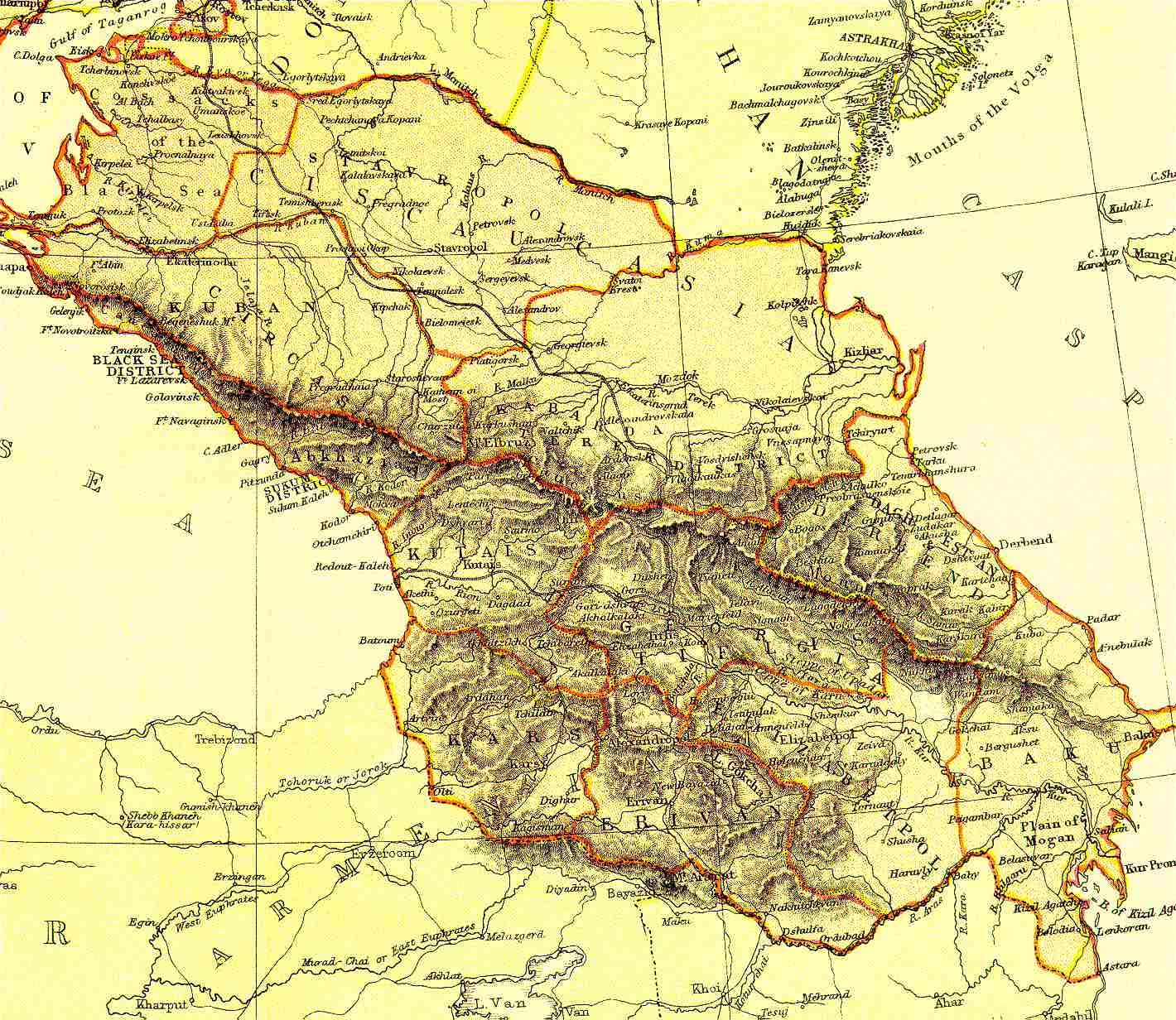

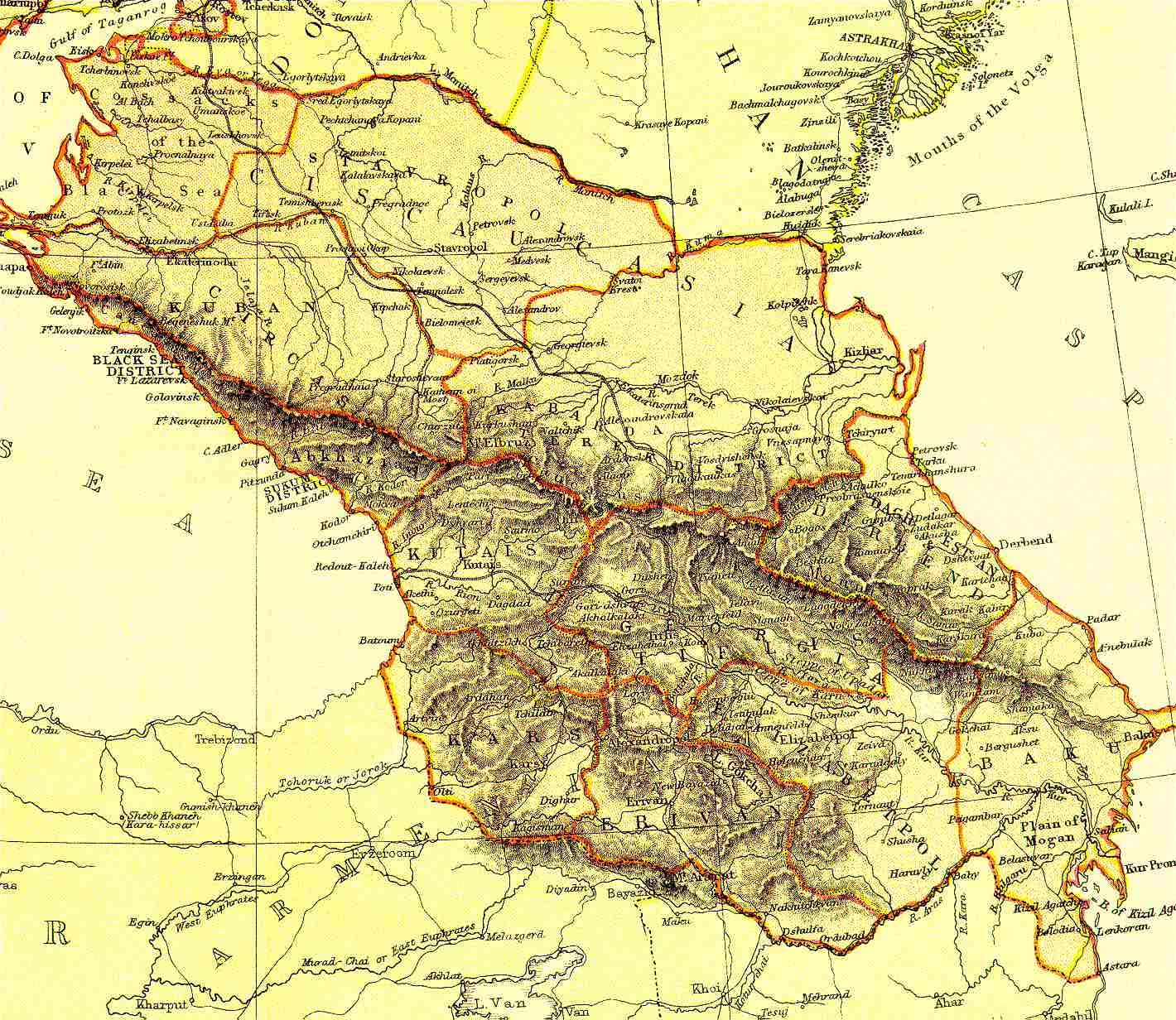

The country of

By the 15th century, the Christian

By the 15th century, the Christian  Vakhtang's successor, Heraclius II, king of

Vakhtang's successor, Heraclius II, king of

After Giorgi's death on 28 December 1800, the kingdom was torn between the claims of two rival heirs,

After Giorgi's death on 28 December 1800, the kingdom was torn between the claims of two rival heirs,

However, Solomon was far from submissive. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret negotiations with the former. In February 1810, a Russian decree proclaimed that Solomon was dethroned and ordered Imeretians to pledge allegiance to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded the country, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped that Russia, distracted by its wars with the Ottomans and Persia, would allow Imereti to become autonomous. The Russians eventually crushed the guerrilla uprising but they could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) put an end to the king's hopes of foreign support (he had also tried to interest

However, Solomon was far from submissive. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret negotiations with the former. In February 1810, a Russian decree proclaimed that Solomon was dethroned and ordered Imeretians to pledge allegiance to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded the country, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped that Russia, distracted by its wars with the Ottomans and Persia, would allow Imereti to become autonomous. The Russians eventually crushed the guerrilla uprising but they could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) put an end to the king's hopes of foreign support (he had also tried to interest

Over the years, after they had made sufficient payments to compensate the landlords, this land would become their own private property. In the event, the reforms pleased neither nobles nor the ex-serfs. Though they were now free peasants, the ex-serfs were still subject to the heavy financial burden of paying rent and it usually took decades before they were able to buy the land for themselves. In other words, they were still dependent on the nobles, not legally, but economically. The nobles had accepted the emancipation only with extreme reluctance and, though they had been more favourably treated than landowners in much of the rest of the empire, they had still lost some of their power and income. In the following years, both peasant and noble discontent would come to be expressed in new political movements in Georgia.

Over the years, after they had made sufficient payments to compensate the landlords, this land would become their own private property. In the event, the reforms pleased neither nobles nor the ex-serfs. Though they were now free peasants, the ex-serfs were still subject to the heavy financial burden of paying rent and it usually took decades before they were able to buy the land for themselves. In other words, they were still dependent on the nobles, not legally, but economically. The nobles had accepted the emancipation only with extreme reluctance and, though they had been more favourably treated than landowners in much of the rest of the empire, they had still lost some of their power and income. In the following years, both peasant and noble discontent would come to be expressed in new political movements in Georgia.

On Google Books

/ref> Because Georgia served as more-or-less a Russian

In the 1830s,

In the 1830s,

In the mid-19th century, Romantic patriotism gave way to a more overtly political national movement in Georgia. This began with a young generation of Georgian students educated at

In the mid-19th century, Romantic patriotism gave way to a more overtly political national movement in Georgia. This began with a young generation of Georgian students educated at

In 1881, the reforming Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by Russian populists in Saint Petersburg. His successor Alexander III was much more autocratic and frowned on any expression of national independence as a threat to his empire. In an effort to introduce more central control, he abolished the Caucasus Viceroyalty, reducing Georgia's status to that of any other Russian province. Study of the

In 1881, the reforming Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by Russian populists in Saint Petersburg. His successor Alexander III was much more autocratic and frowned on any expression of national independence as a threat to his empire. In an effort to introduce more central control, he abolished the Caucasus Viceroyalty, reducing Georgia's status to that of any other Russian province. Study of the

The 1890s and early 1900s were marked by frequent strikes throughout Georgia. The peasants, too, were still discontented, and the

The 1890s and early 1900s were marked by frequent strikes throughout Georgia. The peasants, too, were still discontented, and the

Russia entered

Russia entered

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

became part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in the 19th century. Throughout the early modern period, the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Ottoman and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

empires had fought over various fragmented Georgian kingdoms and principalities; by the 18th century, Russia emerged as the new imperial power in the region. Since Russia was an Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churche ...

state like Georgia, the Georgians increasingly sought Russian help. In 1783, Heraclius II of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti

The Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti ( ka, ქართლ-კახეთის სამეფო, tr) (1762–1801

) was created in 1762 by the unification of two eastern Georgian kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti. From the early 16th century, accord ...

forged an alliance with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, whereby the kingdom became a Russian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

and abjured any dependence on its suzerain Persia. The Russo-Georgian alliance, however, backfired as Russia was unwilling to fulfill the terms of the treaty, proceeding to annex the troubled kingdom in 1801, and reducing it to the status of a Russian region (Georgia Governorate

The Georgian Governorate (russian: Грузинская губерния; ka, საქართველოს გუბერნია) was one of the '' guberniyas'' of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire. Its capital was Tiflis (T ...

). In 1810, the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti

Imereti ( Georgian: იმერეთი) is a region of Georgia situated in the central-western part of the republic along the middle and upper reaches of the Rioni River. Imereti is the most populous region in Georgia. It consists of 11 munic ...

was annexed as well. Russian rule over Georgia was eventually acknowledged in various peace treaties with Persia and the Ottomans, and the remaining Georgian territories were absorbed by the Russian Empire in a piecemeal fashion in the course of the 19th century.

Until 1918, Georgia would be part of the Russian Empire. Russian rule offered the Georgians security from external threats, but it was also often heavy-handed and insensitive to locals. By the late 19th century, discontent with the Russian authorities led to a growing national movement. The Russian Imperial period, however, brought unprecedented social and economic change to Georgia, with new social classes emerging: the emancipation of the serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

freed many peasants but did little to alleviate their poverty; the growth of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

created an urban working class in Georgia. Both peasants and workers found expression for their discontent through revolts and strikes, culminating in the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. Their cause was championed by the socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

s, who became the dominant political force in Georgia in the final years of Russian rule. Georgia finally won its independence in 1918, less as a result of the nationalists' and socialists' efforts, than from the collapse of the Russian Empire in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Background: Russo-Georgian relations before 1801

By the 15th century, the Christian

By the 15th century, the Christian Kingdom of Georgia

The Kingdom of Georgia ( ka, საქართველოს სამეფო, tr), also known as the Georgian Empire, was a medieval Eurasian monarchy that was founded in circa 1008 AD. It reached its Golden Age of political and economic ...

had become fractured into a series of smaller states which were fought over by the two great Muslim empires in the region, Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and Safavid Persia

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

. The Peace of Amasya

The Peace of Amasya ( fa, پیمان آماسیه ("Peymān-e Amasiyeh"); tr, Amasya Antlaşması) was a treaty agreed to on May 29, 1555, between Shah Tahmasp of Safavid Iran and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire at the cit ...

of 1555 formally divided the lands of the south Caucasus into separate Ottoman and Persian spheres of influence. The Georgian Kingdom of Imereti

The Kingdom of Imereti ( ka, იმერეთის სამეფო, tr) was a Georgian monarchy established in 1455 by a member of the house of Bagrationi when the Kingdom of Georgia was dissolved into rival kingdoms. Before that time, Im ...

and Principality of Samtskhe

The Samtskhe-Saatabago or Samtskhe Atabegate ( ka, სამცხე-საათაბაგო), also called the Principality of Samtskhe (სამცხის სამთავრო), was a Georgian feudal principality in Zemo Kartli, ru ...

, as well as the lands along the Black Sea coast to its west were accorded to the Ottomans. To the east, the Georgian kingdoms of Kartli

Kartli ( ka, ქართლი ) is a historical region in central-to-eastern Georgia traversed by the river Mtkvari (Kura), on which Georgia's capital, Tbilisi, is situated. Known to the Classical authors as Iberia, Kartli played a crucial role ...

and Kakheti

Kakheti ( ka, კახეთი ''K’akheti''; ) is a region (mkhare) formed in the 1990s in eastern Georgia from the historical province of Kakheti and the small, mountainous province of Tusheti. Telavi is its capital. The region comprises eigh ...

and various Muslim potentates along the Caspian Sea coast were subsumed under Persian control.

But during the second half of the century a third imperial power emerged to the north, namely the Russian state of Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

* Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domes ...

, which shared Georgia's Orthodox religion. Diplomatic contacts between the Georgian Kingdom of Kakheti

The Second Kingdom of Kakheti ( ka, კახეთის სამეფო, tr; also spelled Kaxet'i or Kakhetia) was a late medieval/ early modern monarchy in eastern Georgia, centered at the province of Kakheti, with its capital first at Grem ...

and Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

began in 1558 and in 1589, Tsar Fyodor I offered to put the kingdom under his protection. Yet little help was forthcoming and the Russians were still too remote from the south Caucasus region to challenge Ottoman or Persian control and hegemony successfully. Only in the early 18th century did Russia start to make serious military inroads south of the Caucasus. In 1722, Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

exploited the chaos and turmoil in the Safavid Persian Empire to lead an expedition against it, while he struck an alliance with Vakhtang VI

Vakhtang VI ( ka, ვახტანგ VI), also known as Vakhtang the Scholar, Vakhtang the Lawgiver and Ḥosaynqolī Khan ( fa, حسینقلی خان, translit=Hoseyn-Qoli Xān) (September 15, 1675 – March 26, 1737), was a Georgian ...

, the Georgian ruler of Kartli and the Safavid-appointed governor of the region. However, the two armies failed to link up and the Russians retreated northward again, leaving the Georgians to the mercy of the Persians. Vakhtang ended his days in exile in Russia.

Kartli-Kakheti

The Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti ( ka, ქართლ-კახეთის სამეფო, tr) (1762–1801

) was created in 1762 by the unification of two eastern Georgian kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti. From the early 16th century, accord ...

from 1762 to 1798, turned towards Russia for protection against Ottoman and Persian attacks. The kings of the other major Georgian state, Imereti

Imereti ( Georgian: იმერეთი) is a region of Georgia situated in the central-western part of the republic along the middle and upper reaches of the Rioni River. Imereti is the most populous region in Georgia. It consists of 11 munic ...

(in Western Georgia), also contacted Russia, seeking protection against the Ottomans. Russian empress Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

undertook a series of initiatives to enhance Russian influence in the Caucasus and strengthen the Russian presence on the ground. These involved reinforcing the defensive lines that had been established earlier in the century by Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

, moving more Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

into the region to serve as border guards, and building new forts.

War broke out between the Russians and Ottomans in 1768, as both empires sought to secure their power in the Caucasus. In 1769–1772, a handful of Russian troops under General Totleben battled against Turkish invaders in Imereti

Imereti ( Georgian: იმერეთი) is a region of Georgia situated in the central-western part of the republic along the middle and upper reaches of the Rioni River. Imereti is the most populous region in Georgia. It consists of 11 munic ...

and Kartli-Kakheti

The Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti ( ka, ქართლ-კახეთის სამეფო, tr) (1762–1801

) was created in 1762 by the unification of two eastern Georgian kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti. From the early 16th century, accord ...

. The course cut by Totleben and his troops as they moved from north to south over the centre of the Caucasian Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

laid the groundwork for what would come to be formalised through Russian investment over the next century as the Georgian Military Highway

The Georgian Military Road or Georgian Military Highway (, 'sakartvelos samkhedro gza'' , os, Арвыкомы фæндаг 'Arvykomy fændag'' is the historic name for a major route through the Caucasus from Georgia (country), Georgia ...

, the major overland route through the mountains. The war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

between the Russians and Ottomans was concluded in 1774 with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayna ...

.

In 1783, Heraclius II signed the Treaty of Georgievsk

The Treaty of Georgievsk (russian: Георгиевский трактат, Georgievskiy traktat; ka, გეორგიევსკის ტრაქტატი, tr) was a bilateral treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and the east Ge ...

with Catherine, according to which Kartli-Kakheti agreed to forswear allegiance to any state except Russia, in return for Russian protection. But when another Russo-Turkish War broke out in 1787, the Russians withdrew their troops from the region for use elsewhere, leaving Heraclius's kingdom unprotected. In 1795, the new Persian shah, Agha Mohammed Khan

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar ( fa, آقا محمد خان قاجار, translit=Âqâ Mohammad Xân-e Qâjâr; 14 March 1742 – 17 June 1797), also known by his regnal name of Agha Mohammad Shah (, ), was the founder of the Qajar dynasty of Iran, ru ...

issued an ultimatum to Heraclius, ordering him to break off relations with Russia or face invasion. Heraclius ignored it, counting on Russian help, which did not arrive. Agha Mohammad Khan carried out his threat and captured and burned the capital, Tbilisi, to the ground, as he sought to re-establish Persia's traditional suzerainty over the region.

The Russian annexations

Eastern Georgia

In spite of Russia's failure to honour the terms of the Treaty of Georgievsk, Georgian rulers felt they had nowhere else to turn. The Persians had sacked and burned Tbilisi, leaving 20,000 dead.Agha Mohammad Khan

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar ( fa, آقا محمد خان قاجار, translit=Âqâ Mohammad Xân-e Qâjâr; 14 March 1742 – 17 June 1797), also known by his regnal name of Agha Mohammad Shah (, ), was the founder of the Qajar dynasty of Iran, rul ...

, however, was assassinated in 1797 in Shusha

/ hy, Շուշի

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline = ShushaCollection2021.jpg

, image_caption = Landmarks of Shusha, from top left:Ghazanchetsots Cathedral • Yukhari Govhar ...

, after which the Iranian grip over Georgia softened. Heraclius died the following year, leaving the throne to his sickly and ineffectual son Giorgi XII.

Davit

Boat suspended from radial davits; the boat is mechanically lowered

Gravity multi-pivot on Scandinavia''

file:Bossoir a gravité.jpg, Gravity Roller Davit

file:Davits-starbrd.png, Gravity multi-pivot davit holding rescue vessel on North Sea ferr ...

and Iulon. However, Tsar Paul I of Russia

Paul I (russian: Па́вел I Петро́вич ; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination. Officially, he was the only son of Peter III of Russia, Peter III and Catherine the Great, although Catherine hinted that he w ...

had already decided neither candidate would be crowned king. Instead, the monarchy would be abolished and the country administered by Russia. He signed a decree on the incorporation of Kartli-Kakheti into the Russian Empire which was confirmed by Tsar Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

on 12 September 1801. The Georgian envoy in Saint Petersburg, Garsevan Chavchavadze

Prince Garsevan Chavchavadze ( ka, გარსევან ჭავჭავაძე) (July 20, 1757 - April 7, 1811) was a Georgian nobleman (''tavadi''), politician and diplomat primarily known as the Georgian ambassador to Imperial Russia.

...

, reacted with a note of protest that was presented to the Russian vice-chancellor Alexander Kurakin. In May 1801, Russian General Carl Heinrich von Knorring removed the Georgian heir to the throne, David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

Batonishvili

''Batonishvili'' ( ka, ბატონიშვილი) (literally "a child of batoni (lord or sovereign)" in Georgian) is a title for royal princes and princesses who descend from the kings of Georgia from the Bagrationi dynasty and is suffixe ...

, from power and deployed a provisional government headed by General Ivan Petrovich Lazarev. Knorring had secret orders to remove all the male and some female members of the royal family to Russia. Some of the Georgian nobility did not accept the decree until April 1802, when General Knorring held the nobility in Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the Capital city, capital and the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia, lying on the ...

's Sioni Cathedral and forced them to take an oath on the imperial crown of Russia. Those who disagreed were arrested.

Now that Russia was able to use Georgia as a bridgehead for further expansion south of the Caucasus, Persia and the Ottoman Empire felt threatened. In 1804, Pavel Tsitsianov

Prince Pavel Dmitriyevich Tsitsianov (russian: Павел Дмитриевич Цицианов), also known as Pavle Dimitris dze Tsitsishvili ( ka, პავლე ციციშვილი; —) was a Georgian nobleman and a prominent general ...

, the commander of Russian forces in the Caucasus, attacked Ganja

Ganja (, ; ) is one of the oldest and most commonly used synonyms for marijuana. Its usage in English dates to before 1689.

Etymology

''Ganja'' is borrowed from Hindi/Urdu ( hi, गांजा, links=no, ur, , links=no, IPA: �aːɲd� ...

, provoking the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813. This was followed by the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histor ...

of 1806–12 with the Ottomans, who were unhappy with Russian expansion in Western Georgia. Georgian attitudes were mixed: some fought as volunteers helping the Russian army, others rebelled against Russian rule (there was a major uprising in the highlands of Kartli-Kakheti in 1804). Both wars ended in Russian victory, with the Ottomans and Persians recognising the tsar's claims over Georgia (by the Treaty of Bucharest with Turkey and the Treaty of Gulistan

The Treaty of Gulistan (russian: Гюлистанский договор; fa, عهدنامه گلستان) was a peace treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and Iran on 24 October 1813 in the village of Gulistan (now in the Goranboy Distri ...

with Persia).

Western Georgia

Solomon II of Imereti

Solomon II ( ka, სოლომონ II) (1772 – February 7, 1815), of the Bagrationi Dynasty, was the last King of Imereti (western Georgia) from 1789 to 1790 and from 1792 until his deposition by the Imperial Russian government in 1810.

H ...

was angry at the Russian annexation of Kartli-Kakheti. He offered a compromise: he would make Imereti a Russian protectorate if the monarchy and autonomy of his neighbour was restored. Russia made no reply. In 1803, the ruler of Mingrelia

Mingrelia ( ka, სამეგრელო, tr; xmf, სამარგალო, samargalo; ab, Агырны, Agirni) is a historic province in the western part of Georgia, formerly known as Odishi. It is primarily inhabited by the Mingrelian ...

, a region belonging to Imereti, rebelled against Solomon and acknowledged Russia as his protector instead. When Solomon refused to make Imereti a Russian protectorate too, the Russian general Tsitsianov invaded and on 25 April 1804, Solomon signed a treaty making him a Russian vassal. However, Solomon was far from submissive. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret negotiations with the former. In February 1810, a Russian decree proclaimed that Solomon was dethroned and ordered Imeretians to pledge allegiance to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded the country, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped that Russia, distracted by its wars with the Ottomans and Persia, would allow Imereti to become autonomous. The Russians eventually crushed the guerrilla uprising but they could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) put an end to the king's hopes of foreign support (he had also tried to interest

However, Solomon was far from submissive. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret negotiations with the former. In February 1810, a Russian decree proclaimed that Solomon was dethroned and ordered Imeretians to pledge allegiance to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded the country, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped that Russia, distracted by its wars with the Ottomans and Persia, would allow Imereti to become autonomous. The Russians eventually crushed the guerrilla uprising but they could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) put an end to the king's hopes of foreign support (he had also tried to interest Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

). Solomon died in exile in Trabzon

Trabzon (; Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (''Trapezous''), Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (''Trapezounta''); Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (''Trapizoni'')), historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the Bl ...

in 1815.

In 1828–29, another Russo-Turkish War ended with Russia adding the major port of Poti

Poti ( ka, ფოთი ; Mingrelian: ფუთი; Laz: ჶაში/Faşi or ფაში/Paşi) is a port city in Georgia, located on the eastern Black Sea coast in the region of Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti in the west of the country. Built near t ...

and the fortress towns of Akhaltsikhe

Akhaltsikhe ( ka, ახალციხე ), formerly known as Lomsia ( ka, ლომსია), is a small city in Georgia's southwestern region (''mkhare'') of Samtskhe–Javakheti. It is situated on both banks of a small river Potskhovi (a left ...

and Akhalkalaki

Akhalkalaki ( ka, ახალქალაქი, tr; hy, Ախալքալաք / Նոր-Քաղաք, translit=Axalk’alak’ / Nor-K’aġak’) is a town in Georgia's southern region of Samtskhe–Javakheti and the administrative centre of the Ak ...

to its possessions in Georgia. From 1803 to 1878, as a result of numerous Russian wars now against Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, several of Georgia's previously lost territories – such as Adjara

Adjara ( ka, აჭარა ''Ach’ara'' ) or Achara, officially known as the Autonomous Republic of Adjara ( ka, აჭარის ავტონომიური რესპუბლიკა ''Ach’aris Avt’onomiuri Resp’ublik’a'' ...

– were also incorporated into the empire. The Principality of Guria

The Principality of Guria ( ka, გურიის სამთავრო, tr) was a historical state in Georgia. Centered on modern-day Guria, a southwestern region in Georgia, it was located between the Black Sea and Lesser Caucasus, and was r ...

was abolished and incorporated into the Empire in 1829, while Svaneti

Svaneti or Svanetia (Suania in ancient sources; ka, სვანეთი ) is a historic province in the northwestern part of Georgia (country), Georgia. It is inhabited by the Svans, an ethnic subgroup of Georgians.

Geography

Situated o ...

was gradually annexed in 1858. Mingrelia

Mingrelia ( ka, სამეგრელო, tr; xmf, სამარგალო, samargalo; ab, Агырны, Agirni) is a historic province in the western part of Georgia, formerly known as Odishi. It is primarily inhabited by the Mingrelian ...

, although a Russian protectorate since 1803, was not absorbed until 1867.

Early years of Russian rule

Integration into the empire

During the first decades of Russian rule, Georgia was placed under military governorship. The land was at the frontline of Russia's war against Turkey and Persia and the commander-in-chief of the Russian army of the region was also the governor. Russia gradually expanded its territory in Transcaucasia at the expense of its rivals, taking large areas of land in the rest of the region, comprising all of modern-dayArmenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

from Qajar Persia

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

through the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828)

The Russo-Persian Wars or Russo-Iranian Wars were a series of conflicts between 1651 and 1828, concerning Persia (Iran) and the Russian Empire. Russia and Persia fought these wars over disputed governance of territories and countries in the Cau ...

and the resulting Treaty of Turkmenchay

The Treaty of Turkmenchay ( fa, عهدنامه ترکمنچای; russian: Туркманчайский договор) was an agreement between Qajar Iran and the Russian Empire, which concluded the Russo-Persian War (1826–28). It was second o ...

. At the same time the Russian authorities aimed to integrate Georgia into the rest of their empire. Russian and Georgian societies had much in common: the main religion was Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Late antiquity, A ...

and in both countries a land-owning aristocracy ruled over a population of serfs. Initially, Russian rule proved high-handed, arbitrary and insensitive to local law and customs. In 1811, the autocephaly

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern O ...

(i.e. independent status) of the Georgian Orthodox Church

The Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia ( ka, საქართველოს სამოციქულო ავტოკეფალური მართლმადიდებელი ეკლესია, tr), commonly ...

was abolished, the Catholicos Anton II was deported to Russia and Georgia became an exarchate

An exarchate is any territorial jurisdiction, either secular or ecclesiastical, whose ruler is called an exarch. The term originates from the Greek word ''arkhos'', meaning a leader, ruler, or chief. Byzantine Emperor Justinian I created the firs ...

of the Russian Church.

The Russian government also managed to alienate many Georgian nobles, prompting a group of young aristocrats to plot to overthrow Russian rule. They were inspired by events elsewhere in the Russian Empire: the Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

in St. Petersburg in 1825 and the Polish uprising

This is a chronological list of military conflicts in which Polish armed forces fought or took place on Polish territory from the reign of Mieszko I (960–992) to the ongoing military operations.

This list does not include peacekeeping operation ...

against the Russians in 1830. The Georgian nobles' plan was simple: they would invite all the Russian officials in the region to a ball then murder them. However, the conspiracy was discovered by the authorities on 10 December 1832 and its members were arrested and internally exiled elsewhere in the Russian Empire. There was a revolt by peasants and nobles in Guria in 1841. Things changed with the appointment of Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov

Prince Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov (russian: Князь Михаи́л Семёнович Воронцо́в, tr. ; ) was a Russian nobleman and field-marshal, renowned for his success in the Napoleonic wars and most famous for his participati ...

as Viceroy of the Caucasus in 1845. Count Vorontsov's new policies won over the Georgian nobility, who increasingly adopted Western European customs and attire, as the Russian nobility had done in the previous century.

Georgian society

When Russian rule began in the early 19th century Georgia was still ruled by royal families of the various Georgian states, but these were then deposed by the Russians and sent into internal exile elsewhere in the empire. Beneath them were the nobles, who constituted about 5 percent of the population and protected their power and privileges. They owned most of the land, which was worked by theirserf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s. Peasants made up the bulk of Georgian society. The rural economy

Rural economics is the study of rural economies. Rural economies include both agricultural and non-agricultural industries, so rural economics has broader concerns than agricultural economics which focus more on food systems. Rural developmen ...

had become seriously depressed during the period of Ottoman and Persian domination and most Georgian serfs lived in dire poverty, subject to the frequent threat of starvation. Famine would often prompt them to rebellion, such as the major revolt in Kakheti

Kakheti ( ka, კახეთი ''K’akheti''; ) is a region (mkhare) formed in the 1990s in eastern Georgia from the historical province of Kakheti and the small, mountainous province of Tusheti. Telavi is its capital. The region comprises eigh ...

in 1812.

Emancipation of the serfs

Serfdom was a problem not just in Georgia but throughout most of the Russian Empire. By the mid-19th century the issue of freeing the serfs had become impossible to ignore any longer if Russia was to be reformed and modernised. In 1861,Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Fin ...

abolished serfdom in Russia proper. The tsar also wanted to emancipate the serfs of Georgia, but without losing the recently earned loyalty of the nobility whose power and income depended on serf labour. This called for delicate negotiations and the task of finding a solution that would be acceptable to the land-owners was entrusted to the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

noble Dimitri Kipiani

Prince Dimitri Ivanes dze Kipiani ( ka, დიმიტრი ყიფიანი alternatively spelled as Qipiani) (April 14, 1814 – October 24, 1887) was a Georgian statesman, publicist, writer and translator. A leader of Georgia's liberal ...

. On 13 October 1865, the tsar decreed the emancipation of the first serfs in Georgia. The process of abolition throughout all the traditional Georgian lands would last into the 1870s. The serfs became free peasants who could move where they liked, marry whom they chose and take part in political activity without asking their lords' permission. The nobles retained the title to all their land but it was to be divided into two parts. The nobles owned one of these parts (at least half of the land) outright, but the other was to be rented by the peasants who had lived and worked on it for centuries.

Over the years, after they had made sufficient payments to compensate the landlords, this land would become their own private property. In the event, the reforms pleased neither nobles nor the ex-serfs. Though they were now free peasants, the ex-serfs were still subject to the heavy financial burden of paying rent and it usually took decades before they were able to buy the land for themselves. In other words, they were still dependent on the nobles, not legally, but economically. The nobles had accepted the emancipation only with extreme reluctance and, though they had been more favourably treated than landowners in much of the rest of the empire, they had still lost some of their power and income. In the following years, both peasant and noble discontent would come to be expressed in new political movements in Georgia.

Over the years, after they had made sufficient payments to compensate the landlords, this land would become their own private property. In the event, the reforms pleased neither nobles nor the ex-serfs. Though they were now free peasants, the ex-serfs were still subject to the heavy financial burden of paying rent and it usually took decades before they were able to buy the land for themselves. In other words, they were still dependent on the nobles, not legally, but economically. The nobles had accepted the emancipation only with extreme reluctance and, though they had been more favourably treated than landowners in much of the rest of the empire, they had still lost some of their power and income. In the following years, both peasant and noble discontent would come to be expressed in new political movements in Georgia.

Immigration

During the reign ofNicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

, Russian authorities encouraged the migration of various religious minorities, such as Molokan

The Molokans ( rus, молокан, p=məlɐˈkan or , "dairy-eater") are a Spiritual Christian sect that evolved from Eastern Orthodoxy in the East Slavic lands. Their traditions—especially dairy consumption during Christian fasts—did not ...

s and Doukhobor

The Doukhobours or Dukhobors (russian: духоборы / духоборцы, dukhobory / dukhobortsy; ) are a Spiritual Christian ethnoreligious group of Russian origin. They are one of many non-Orthodox ethno-confessional faiths in Russia a ...

s, from Russia's heartland provinces into Transcaucasia, including Georgia. The intent was both to isolate the troublesome dissenters away from the Orthodox Russians (who could be "corrupted" by their ideas), and to strengthen Russian presence in the region.Daniel H. Shubin, "A History of Russian Christianity". Volume III, pages 141-148. Algora Publishing, 2006.On Google Books

/ref> Because Georgia served as more-or-less a Russian

march

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of Marc ...

principality as a base for further expansion against the Ottoman Empire, other Christian communities from the Transcaucasus region were settled there in the 19th century, particularly Armenians and Caucasus Greeks

The Caucasus Greeks ( el, Έλληνες του Καυκάσου or more commonly , tr, Kafkas Rum), also known as the Greeks of Transcaucasia and Russian Asia Minor, are the ethnic Greeks of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia in what is now ...

. These subsequently often fought alongside Russians and Georgians in the Russian Caucasus Army in its wars against the Ottomans, helping capture territories in the South Caucasus bordering Georgia that became the Russian militarily administered provinces of Batumi Oblast

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of th ...

and Kars Oblast

The Kars Oblast was a province (''oblast'') of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire between 1878 and 1917. Its capital was the city of Kars, presently in Turkey. The ''oblast'' bordered the Ottoman Empire to the west, the Batum Oblast ...

, where tens of thousands of Armenians, Caucasus Greeks, Russians, and other ethnic minority communities living in Georgia were re-settled.

Cultural and political movements

Incorporation into the Russian Empire changed Georgia's orientation away from theMiddle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and towards Europe as members of the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

began to read about new ideas from the West. At the same time, Georgia shared many social problems with the rest of Russia, and the Russian political movements that emerged in the 19th century looked to also extend their following in Georgia.

Romanticism

In the 1830s,

In the 1830s, Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

began to influence Georgian literature, which enjoyed a revival thanks to famous poets such as Alexander Chavchavadze

Prince Alexander Chavchavadze ( ka, ალექსანდრე ჭავჭავაძე, russian: Александр Чавчавадзе; 1786 – November 6, 1846) was a Georgian poet, public benefactor and military figure. Regarded as th ...

, Grigol Orbeliani

Prince Grigol Orbeliani or Jambakur-Orbeliani ( ka, გრიგოლ ორბელიანი; ჯამბაკურ-ორბელიანი) (2 October 1804 – 21 March 1883) was a Georgian Romanticist poet and general in Imper ...

and, above all, Nikoloz Baratashvili

Prince Nikoloz "Tato" Baratashvili ( ka, ნიკოლოზ "ტატო" ბარათაშვილი; 4 December 1817 – 21 October 1845) was a Georgian poet. He was one of the first Georgians to marry modern nationalism with European R ...

. They began to explore Georgia's past, seeking a lost golden age which they used as an inspiration for their works. One of Baratashvili's best-known poems, ''Bedi Kartlisa'' ("Georgia's Fate"), expresses his deep ambivalence about the union with Russia in the phrase "what pleasure does the nightingale receive from honour if it is in a cage?"

Georgia became a theme in Russian literature as well. In 1829, Russia's greatest poet Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

visited the country and his experience is reflected in several of his lyrics. His younger contemporary, Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (; russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjurʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲɛrməntəf; – ) was a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucas ...

, was exiled to the Caucasus in 1840. The region appears as a land of exotic adventure in Lermontov's famous novel ''A Hero of Our Time

''A Hero of Our Time'' ( rus, Герой нашего времени, links=1, r=Gerój nášego vrémeni, p=ɡʲɪˈroj ˈnaʂɨvə ˈvrʲemʲɪnʲɪ) is a novel by Mikhail Lermontov, written in 1839, published in 1840, and revised in 1841.

It ...

'' and he also celebrated Georgia's wild, mountainous landscape in the long poem ''Mtsyri'', about a novice monk who escapes from the strictness of religious discipline to find freedom in nature.

Nationalism

In the mid-19th century, Romantic patriotism gave way to a more overtly political national movement in Georgia. This began with a young generation of Georgian students educated at

In the mid-19th century, Romantic patriotism gave way to a more overtly political national movement in Georgia. This began with a young generation of Georgian students educated at Saint Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the G ...

, who were nicknamed the ''tergdaleulnis'' (after the Terek River

The Terek (; , Tiyrk; , Tərč; , ; , ; , ''Terk''; , ; , ) is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It originates in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of Georgia (country), Georgia and flows through North Caucasus region of Russia into the Casp ...

which flows through Georgia and Russia). The most outstanding figure by far was the writer Ilia Chavchavadze

Prince Ilia Chavchavadze ( ka, ილია ჭავჭავაძე; 8 November 1837 – 12 September 1907) was a Georgian public figure, journalist, publisher, writer and poet who spearheaded the revival of Georgian nationalism during the ...

, who was the most influential Georgian nationalist before 1905. He sought to improve the position of Georgians within a system that favoured Russian-speakers and turned his attention to cultural matters, especially linguistic reform and the study of folklore. Chavchavadze became more and more conservative, seeing it as his task to preserve Georgian traditions and ensure Georgia remained a rural society. The so-called second generation (''meore dasi'') of Georgian nationalists was less conservative than Chavchavadze. They focused more on the growing cities in Georgia, trying to ensure that urban Georgians could compete with the economically dominant Armenians and Russians. The leading figure in this movement was Niko Nikoladze

Niko Nikoladze ( ka, ნიკო ნიკოლაძე) (27 September 1843 – 5 June 1928) was a Georgian writer, pro-Western enlightener, and public figure primarily known for his contributions to the development of Georgian liberal journali ...

, who was attracted to Western liberal ideas. Nikoladze believed that a Caucasus-wide federation of nations was the best format for resisting tsarist autocracy, a notion not accepted by many of his contemporaries.

Socialism

By the 1870s, alongside these conservative and liberal nationalist trends, a third, more radical political force had emerged in Georgia. Its members focused on social problems and tended to ally themselves with movements in the rest of Russia. The first stirrings were seen in the attempt to spread Russianpopulism

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

to the region, though the populists had little practical effect. Socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, particularly Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, proved far more influential in the long run.

Industrialisation had come to Georgia in the late 19th century, particularly to the towns of Tbilisi, Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of th ...

and Kutaisi

Kutaisi (, ka, ქუთაისი ) is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world and the third-most populous city in Georgia, traditionally, second in importance, after the capital city of Tbilisi. Situated west of Tbilis ...

. With it had come factories, railways and a new, urban working class. In the 1890s, they became the focus of a "third generation" (''Mesame Dasi

Mesame Dasi (Georgian: მესამე დასი) was the first social-democratic party in the Caucasus, based in Tbilisi, Georgia. It was founded in 1892 by Egnate Ninoshvili and M. G. Tskhakaya as a literary-political group, and became aff ...

'') of Georgian intellectuals who called themselves Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, and they included Noe Zhordania

Noe Zhordania ( ka, ნოე ჟორდანია /nɔɛ ʒɔrdɑniɑ/; russian: Ной Никола́евич Жорда́ния; born (or ) — January 11, 1953) was a Georgian journalist and Menshevik politician. He played an eminent role ...

and Filipp Makharadze

Filipp Yeseyevich Makharadze ( ka, ფილიპე მახარაძე, russian: Филипп Махарадзе; 9 March 1868 – 10 December 1941) was a Georgian Bolshevik revolutionary and government official.

Life

Born in the villag ...

, who had learned about Marxism elsewhere in the Russian Empire. They would become the leading force in Georgian politics from 1905 onwards. They believed that the tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

should be overthrown and replaced by democracy, which would eventually create a socialist society.

Later Russian rule

Increasing tensions

In 1881, the reforming Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by Russian populists in Saint Petersburg. His successor Alexander III was much more autocratic and frowned on any expression of national independence as a threat to his empire. In an effort to introduce more central control, he abolished the Caucasus Viceroyalty, reducing Georgia's status to that of any other Russian province. Study of the

In 1881, the reforming Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by Russian populists in Saint Petersburg. His successor Alexander III was much more autocratic and frowned on any expression of national independence as a threat to his empire. In an effort to introduce more central control, he abolished the Caucasus Viceroyalty, reducing Georgia's status to that of any other Russian province. Study of the Georgian language

Georgian (, , ) is the most widely-spoken Kartvelian language, and serves as the literary language or lingua franca for speakers of related languages. It is the official language of Georgia and the native or primary language of 87.6% of its p ...

was discouraged and the very name "Georgia" (russian: Грузия, ka, საქართველო) was banned from newspapers. In 1886, a Georgian student killed the rector of the Tbilisi seminary in protest. When the ageing Dimitri Kipiani

Prince Dimitri Ivanes dze Kipiani ( ka, დიმიტრი ყიფიანი alternatively spelled as Qipiani) (April 14, 1814 – October 24, 1887) was a Georgian statesman, publicist, writer and translator. A leader of Georgia's liberal ...

criticised the head of the Church in Georgia for attacking the seminary students, he was exiled to Stavropol

Stavropol (; rus, Ставрополь, p=ˈstavrəpəlʲ) is a city and the administrative centre of Stavropol Krai, Russia. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 547,820, making it one of Russia's fastest growing cities.

It was known as ...

, where he was mysteriously murdered. Many Georgians believed his death was the work of tsarist agents and mounted a huge anti-Russian demonstration at his funeral.

The revolution of 1905

Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

won peasants and urban workers over to their cause. At this stage, the Georgian Social Democrats still saw themselves as part of an all-Russian political movement. However, at the Second Congress of the all-Russian Social Democratic Party held in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

in 1903, the party split into two irreconcilable groups: the Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

and the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. By 1905, the Social Democratic movement in Georgia had overwhelmingly decided in favour of the Mensheviks and their leader Noe Zhordania

Noe Zhordania ( ka, ნოე ჟორდანია /nɔɛ ʒɔrdɑniɑ/; russian: Ной Никола́евич Жорда́ния; born (or ) — January 11, 1953) was a Georgian journalist and Menshevik politician. He played an eminent role ...

. One of the few Georgians to opt for the Bolshevik faction was the young Ioseb Jughashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

.

In January 1905, the troubles within the Russian Empire came to a head when the army fired on a crowd of demonstrators in Saint Petersburg, killing at least 96 people. The news provoked a wave of protests and strikes throughout the country in what became known as the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. The unrest quickly spread to Georgia, where the Mensheviks had recently co-ordinated a large peasant revolt in the Guria

Guria ( ka, გურია) is a region (''mkhare'') in Georgia, in the western part of the country, bordered by the eastern end of the Black Sea. The region has a population of 113,000 (2016), with Ozurgeti as the regional capital.

Geography

...

region. The Mensheviks were again at the forefront during a year which saw a series of uprisings and strikes, met by the tsarist authorities with a combination of violent repression (carried out by Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

) and concessions. In December, the Mensheviks ordered a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

and encouraged their supporters to bomb the Cossacks, who responded with more bloodshed. The Mensheviks' resort to violence alienated many people, including their Armenian political allies, and the general strike collapsed. All resistance to the tsarist authorities was finally quelled by force in January 1906 with the arrival of an army led by General Maksud Alikhanov

Maksud Alikhanov-Avarsky ( Russian language: Максуд Алиханов-Аварский) (in some documents his name is spelled as Alexander Mikhailovich) (1846-1907) - Russian Lieutenant-General (April 22, 1907), Merv District Head and Tifl ...

.

The years between 1906 and the outbreak of World War I were more peaceful in Georgia, which was now under the rule of a relatively liberal Governor of the Caucasus, Count Ilarion Vorontsov-Dashkov. The Mensheviks believed they had gone too far with the violence of late 1905. Unlike the Bolsheviks, they now rejected the idea of armed insurrection. In 1906, the first elections for a national parliament (the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

) were held in the Russian Empire and the Mensheviks won the seats representing Georgia by a landslide. The Bolsheviks had little support except in the Manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

mine of Chiatura

Chiatura () is a city in the Imereti region of Western Georgia. In 1989, it had a population of about 30,000. The city is known for its system of cable cars connecting the city's center to the mining settlements on the surrounding hills.

The city ...

, though they gained publicity with an armed robbery to gain funds in Tbilisi in 1907. After this incident, Stalin and his colleagues moved to Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

, the only real Bolshevik stronghold in Transcaucasia.

World War I and independence

Russia entered

Russia entered World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

against Germany in August 1914. The war aroused little enthusiasm from the people in Georgia, who did not see much to be gained from the conflict, although 200,000 Georgians were mobilised to fight in the army. When Turkey joined the war on Germany's side in November, Georgia found itself on the frontline. Most Georgian politicians remained neutral, though pro-German feeling and the sense that independence was within reach began to grow among the population.

In 1917, as the Russian war effort collapsed, the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

broke out in Saint Petersburg. The new Provisional Government established a branch to rule Transcaucasia called Ozakom (Extraordinary Committee for Transcaucasia). There was tension in Tbilisi since the mainly Russian soldiers in the city favoured the Bolsheviks, but as 1917 went on, the soldiers began to desert and head northwards, leaving Georgia virtually free from the Russian army and in the hands of the Mensheviks, who rejected the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

that brought the Bolsheviks to power in the Russian capital. Transcaucasia was left to fend for itself and, as the Turkish army began to encroach across the border in February 1918, the question of separation from Russia was brought to the fore.

On 22 April 1918, the parliament of Transcaucasia voted for independence, declaring itself to be the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR; (), (). 22 April – 28 May 1918) was a short-lived state in the Caucasus that included most of the territory of the present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, as well as pa ...

. It was to last for only a month. The new republic was made up of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, each with their different histories, cultures and aspirations. The Armenians were well aware of the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was ...

in Turkey, so for them defence against the invading army was paramount, while the Muslim Azeris were sympathetic to the Turks. The Georgians felt that their interests could best be guaranteed by coming to a deal with the Germans rather than the Turks. On 26 May 1918, Georgia declared its independence and a new state was born, the Democratic Republic of Georgia

The Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG; ka, საქართველოს დემოკრატიული რესპუბლიკა ') was the first modern establishment of a republic of Georgia, which existed from May 1918 to ...

, which would enjoy a brief period of freedom before the Bolsheviks invaded in 1921.Entire "Later Russian rule" section: Suny Chapters 7 and 8

See also

*History of Georgia (country)

The nation of Georgia ( ka, საქართველო ''sakartvelo'') was first unified as a kingdom under the Bagrationi dynasty by the King Bagrat III of Georgia in the early 11th century, arising from a number of predecessor states of ...

References

Sources

* * D.M. Lang: ''A Modern History of Georgia'' (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1962) *Anchabadze, George: ''History of Georgia: A Short Sketch'', Tbilisi, 2005, *Avalov, Zurab: ''Prisoedinenie Gruzii k Rossii'', Montvid, S.-Peterburg 1906 *Gvosdev, Nikolas K.: ''Imperial policies and perspectives towards Georgia: 1760-1819'', Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, * * *Donald Rayfield

Patrick Donald Rayfield OBE (born 12 February 1942, Oxford) is an English academic and Emeritus Professor of Russian and Georgian at Queen Mary University of London. He is an author of books about Russian and Georgian literature, and about Josep ...

, ''Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia'' (Reaktion Books, 2012)

*Nodar Assatiani and Alexandre Bendianachvili, ''Histoire de la Géorgie'' (Harmattan, 1997)

{{Georgia (country) topics

Geography of the Russian Empire

Georgia (country)–Russia relations