Russian anarchist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarchism in Russia has its roots in the early mutual aid systems of the medieval republics and later in the popular resistance to the

In 1848, on his return to

In 1848, on his return to  In January 1869,

In January 1869,

After an assassination attempt, Count

After an assassination attempt, Count

The origin of the Doukhobors dates back to 16th- and 17th-century Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy. The Doukhobors ("Spirit Wrestlers") are a radical Christianity, Christian sect who maintained a belief in

The origin of the Doukhobors dates back to 16th- and 17th-century Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy. The Doukhobors ("Spirit Wrestlers") are a radical Christianity, Christian sect who maintained a belief in

The first anarchist groups to attract a significant following of Russian workers or peasants, were the

The first anarchist groups to attract a significant following of Russian workers or peasants, were the

The anthropologist Eric Wolf asserts that peasants in rebellion are "natural" anarchists. After initially looking favorably upon the Bolsheviks for their proposed land reforms, by 1918 peasants largely came to despise the new government as it became increasingly centralized and exploitative in its dealings with the rural population. Marxist-Leninists had never given the peasants great credit, and with the Civil War against the White movement, White Armies underway, the Red Army primarily used peasant villages as suppliers of grain, which it “requisitioned,” or in other words, seized by force.Vladimir N. Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: Political Parties and Social Movements in Russia, 1918-1922. Princeton, 1994, p. 127-62, 300.

Abused equally by the Red and invading White armies, large groups of peasants, as well as Red Army deserters, formed “Green” armies that resisted the Reds and Whites alike. These forces had no grand political agenda like their enemies, for the most part they simply wanted to stop being harassed and be allowed to govern themselves. Though the Green Armies have largely been ignored by history (and by Soviet historians in particular), they constituted a formidable force and a major threat to Red victory in the Civil War. Even after the party declared the Civil War over in 1920, the Red-Green war persisted for some time.

Red Army generals noted that in many regions peasant rebellions were heavily influenced by anarchist leaders and ideas. In Ukraine, the most notorious peasant rebel leader was an anarchist general named Nestor Makhno. Makhno had originally led his forces in collaboration with the Red Army against the Whites. In the region of Ukraine where his forces were stationed, Makhno oversaw the development of an autonomous system of government based on the productive coordination of communes. According to Peter Marshall, a historian of anarchism, "For more than a year, anarchists were in charge of a large territory, one of the few examples of anarchy in action on a large scale in modern history.

Unsurprisingly, the Bolsheviks came to see Makhno's experiment in self-government as a threat in need of elimination, and in 1920 the Red Army sought to take control of Makhno's forces. They resisted, but the officers (not including Makhno himself) were arrested and executed by the end of 1920. Makhno continued to fight before going into exile in Paris the next year.

The anthropologist Eric Wolf asserts that peasants in rebellion are "natural" anarchists. After initially looking favorably upon the Bolsheviks for their proposed land reforms, by 1918 peasants largely came to despise the new government as it became increasingly centralized and exploitative in its dealings with the rural population. Marxist-Leninists had never given the peasants great credit, and with the Civil War against the White movement, White Armies underway, the Red Army primarily used peasant villages as suppliers of grain, which it “requisitioned,” or in other words, seized by force.Vladimir N. Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: Political Parties and Social Movements in Russia, 1918-1922. Princeton, 1994, p. 127-62, 300.

Abused equally by the Red and invading White armies, large groups of peasants, as well as Red Army deserters, formed “Green” armies that resisted the Reds and Whites alike. These forces had no grand political agenda like their enemies, for the most part they simply wanted to stop being harassed and be allowed to govern themselves. Though the Green Armies have largely been ignored by history (and by Soviet historians in particular), they constituted a formidable force and a major threat to Red victory in the Civil War. Even after the party declared the Civil War over in 1920, the Red-Green war persisted for some time.

Red Army generals noted that in many regions peasant rebellions were heavily influenced by anarchist leaders and ideas. In Ukraine, the most notorious peasant rebel leader was an anarchist general named Nestor Makhno. Makhno had originally led his forces in collaboration with the Red Army against the Whites. In the region of Ukraine where his forces were stationed, Makhno oversaw the development of an autonomous system of government based on the productive coordination of communes. According to Peter Marshall, a historian of anarchism, "For more than a year, anarchists were in charge of a large territory, one of the few examples of anarchy in action on a large scale in modern history.

Unsurprisingly, the Bolsheviks came to see Makhno's experiment in self-government as a threat in need of elimination, and in 1920 the Red Army sought to take control of Makhno's forces. They resisted, but the officers (not including Makhno himself) were arrested and executed by the end of 1920. Makhno continued to fight before going into exile in Paris the next year.

The attempted Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, Third Russian Revolution began in July 1918 with the assassination of the German Ambassador to the Soviet Union in order to prevent the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This was immediately followed by an artillery attack on the Moscow Kremlin, Kremlin and the occupation of the telegraph and telephone buildings by the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Left SRs who sent out several manifestos appealing to the people to rise up against their oppressors and destroy the Bolshevik regime. But whilst this order was not followed by the people of Moscow, the peasants of South Russia responded vigorously to this call to arms. Bands of Chernoe Znamia and Beznachaly anarchist terrorists flared up as rapidly and violently as they had done in 1905. Anarchists in Rostov, Dnipro, Ekaterinoslav and Bryansk, Briansk broke into prisons to liberate the anarchist prisoners and issued fiery proclamations calling on the people to revolt against the Bolshevik regime. The Anarchist Battle Detachments attacked the White movement, Whites, Reds and Germans alike. Many peasants joined the Revolution, attacking their enemies with pitchforks and sickles. Meanwhile, in Moscow, the Underground Anarchists were formed by Kazimir Kovalevich and Piotr Sobalev to be the shock troops of the Revolution, infiltrating Bolshevik ranks and striking when least expected. On 25 September 1919, the Underground Anarchists struck the Bolsheviks with the heaviest blow of the Revolution. The headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party was blown up, killing 12 and injuring 55 Party members, including Nikolai Bukharin and Emilian Iaroslavskii. Spurred on by their apparent success, the Underground Anarchists proclaimed a new "era of dynamite" that would finally wipe away capitalism and the State. The Bolsheviks responded by initiating a new wave of mass arrests in which Kovalevich and Sobalev were the first to be shot. With their leaders dead and much of their organization in tatters, the remaining Underground Anarchists blew themselves up in their last battle with the Cheka, taking much of their safe house with them. Numerous attacks and assassinations occurred frequently until the Revolution finally petered out in 1922. Although the Revolution was mainly a Left SR initiative, it was the Anarchists who had the support of a greater number of the population and they participated in almost all of the attacks the Left SRs organized, and also many on completely their own initiative. The most celebrated figures of the Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, Third Russian Revolution,

The attempted Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, Third Russian Revolution began in July 1918 with the assassination of the German Ambassador to the Soviet Union in order to prevent the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This was immediately followed by an artillery attack on the Moscow Kremlin, Kremlin and the occupation of the telegraph and telephone buildings by the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Left SRs who sent out several manifestos appealing to the people to rise up against their oppressors and destroy the Bolshevik regime. But whilst this order was not followed by the people of Moscow, the peasants of South Russia responded vigorously to this call to arms. Bands of Chernoe Znamia and Beznachaly anarchist terrorists flared up as rapidly and violently as they had done in 1905. Anarchists in Rostov, Dnipro, Ekaterinoslav and Bryansk, Briansk broke into prisons to liberate the anarchist prisoners and issued fiery proclamations calling on the people to revolt against the Bolshevik regime. The Anarchist Battle Detachments attacked the White movement, Whites, Reds and Germans alike. Many peasants joined the Revolution, attacking their enemies with pitchforks and sickles. Meanwhile, in Moscow, the Underground Anarchists were formed by Kazimir Kovalevich and Piotr Sobalev to be the shock troops of the Revolution, infiltrating Bolshevik ranks and striking when least expected. On 25 September 1919, the Underground Anarchists struck the Bolsheviks with the heaviest blow of the Revolution. The headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party was blown up, killing 12 and injuring 55 Party members, including Nikolai Bukharin and Emilian Iaroslavskii. Spurred on by their apparent success, the Underground Anarchists proclaimed a new "era of dynamite" that would finally wipe away capitalism and the State. The Bolsheviks responded by initiating a new wave of mass arrests in which Kovalevich and Sobalev were the first to be shot. With their leaders dead and much of their organization in tatters, the remaining Underground Anarchists blew themselves up in their last battle with the Cheka, taking much of their safe house with them. Numerous attacks and assassinations occurred frequently until the Revolution finally petered out in 1922. Although the Revolution was mainly a Left SR initiative, it was the Anarchists who had the support of a greater number of the population and they participated in almost all of the attacks the Left SRs organized, and also many on completely their own initiative. The most celebrated figures of the Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, Third Russian Revolution,

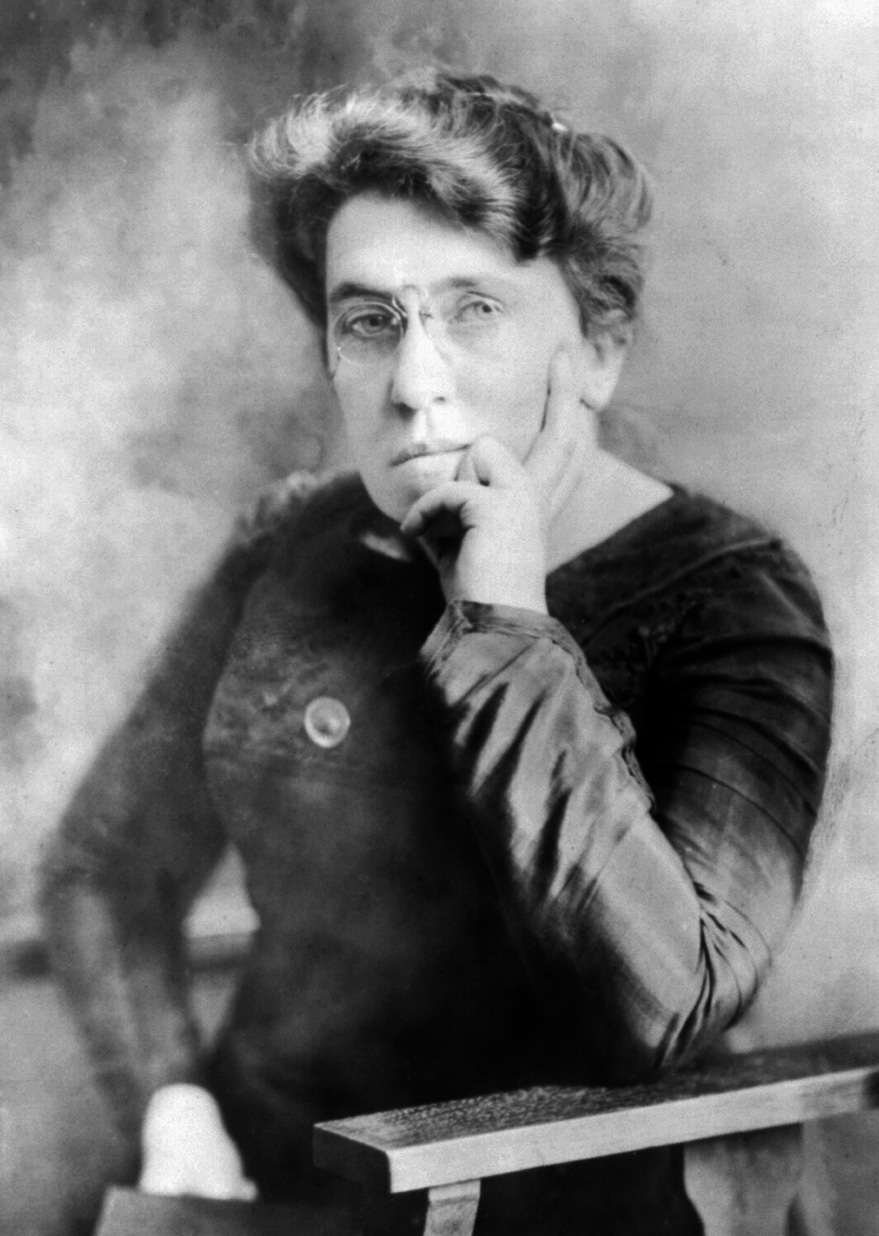

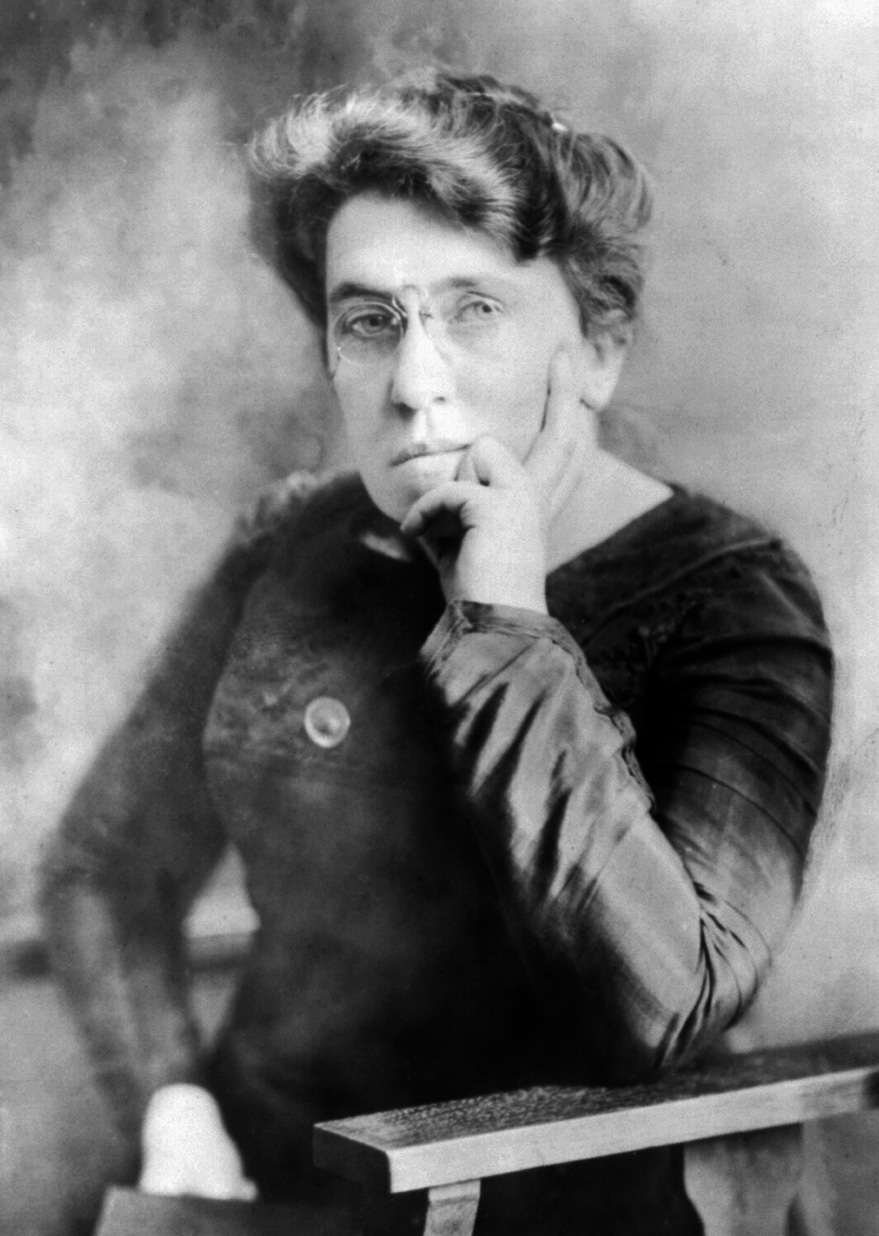

Following the suppression of the anarchist movement in Russia, a number of anarchists fled the country into exile, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Volin, Mark Mratchny, Grigorii Maksimov, Boris Yelensky, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer, who went on to establish relief organizations which provided aid for anarchist political prisoners back in Russia.

Following the suppression of the anarchist movement in Russia, a number of anarchists fled the country into exile, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Volin, Mark Mratchny, Grigorii Maksimov, Boris Yelensky, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer, who went on to establish relief organizations which provided aid for anarchist political prisoners back in Russia.

To the disillusioned Russian anarchist exiles, the experience of the Russian Revolution had fully justified Mikhail Bakunin's earlier declaration that "socialism without liberty is slavery and bestiality." Russian anarchists living abroad began to openly attack the "new kings" of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Communist Party, criticising the NEP as a restoration of capitalism and comparing Vladimir Lenin to the Spanish inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada, the Italian political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre. They positioned themselves in opposition to the Bolshevik government, calling for the destruction of Russian state capitalism and its replacement with workers' self-management by factory committees and workers' council, councils. But while anarchist exiles were united in their criticisms of the Bolshevik government and their recognition that the Russian anarchist movement had collapsed due to its disorganization, their internal divisions remained, with the Anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalists around Grigorii Maksimov, Efim Iarchuk and Alexander Schapiro establishing ''The Workers' Way'' as their organ, while anarcho-communism, anarcho-communists around Peter Arshinov and Volin established ''The Anarchist Herald'' as their own.

The anarcho-syndicalists looked to remedy the issue of anarchist disorganization through the foundation of a new international organization, culminating in the establishment of the IWA–AIT, International Workers' Association (IWA) in December 1922. The IWA analyzed the events of the Russian Revolution as having been a project to build state socialism rather than revolutionary socialism, called for the construction of trade unions to win short-term gains while building towards a general strike and declared their goal to be a social revolution that would abolish centralized states and replace them with a network of workers' councils. Maxmioff later moved to the

To the disillusioned Russian anarchist exiles, the experience of the Russian Revolution had fully justified Mikhail Bakunin's earlier declaration that "socialism without liberty is slavery and bestiality." Russian anarchists living abroad began to openly attack the "new kings" of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Communist Party, criticising the NEP as a restoration of capitalism and comparing Vladimir Lenin to the Spanish inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada, the Italian political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre. They positioned themselves in opposition to the Bolshevik government, calling for the destruction of Russian state capitalism and its replacement with workers' self-management by factory committees and workers' council, councils. But while anarchist exiles were united in their criticisms of the Bolshevik government and their recognition that the Russian anarchist movement had collapsed due to its disorganization, their internal divisions remained, with the Anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalists around Grigorii Maksimov, Efim Iarchuk and Alexander Schapiro establishing ''The Workers' Way'' as their organ, while anarcho-communism, anarcho-communists around Peter Arshinov and Volin established ''The Anarchist Herald'' as their own.

The anarcho-syndicalists looked to remedy the issue of anarchist disorganization through the foundation of a new international organization, culminating in the establishment of the IWA–AIT, International Workers' Association (IWA) in December 1922. The IWA analyzed the events of the Russian Revolution as having been a project to build state socialism rather than revolutionary socialism, called for the construction of trade unions to win short-term gains while building towards a general strike and declared their goal to be a social revolution that would abolish centralized states and replace them with a network of workers' councils. Maxmioff later moved to the  Meanwhile, the anarcho-communists around the ''Dielo Truda, Workers' Cause'' journal began to develop the Platformism, platformist tendency, calling for the construction of a tightly coordinated anarchist organization, which was supported chiefly by Peter Arshinov and Nestor Makhno. This platform was criticized as authoritarian by a number of dissenting voices, including Voline, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer. Arshinov and Makhno's short-tempered response to these criticisms drew the eyre of other Russian exiles such as Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, who denounced them respectively as a "Bolshevik" and a "militarist", while also expressing a distaste with Fleshin and Steimer's factionalism.

During the late 1920s, a number of anarchist exiles decided to return to Russia and appealed to the Soviet government for permission. With the aid of the Right Oppositionist Nikolai Bukharin, Efim Iarchuk was permitted to return in 1925, after which he joined the Communist Party. In 1930, Arshniov also returned to Russia under amnesty and joined the Communist Party, leaving ''Dielo Truda'' in the editorial hands of Grigorii Maksimov. Under Maksimov, the publication took on a notable syndicalist stance while also offering a platform to other anarchist tendencies, becoming the Russian anarchist exiles' most important publication. Maksimov attempted to bridge the divide between the anarcho-syndicalists and anarcho-communists, publishing a

Meanwhile, the anarcho-communists around the ''Dielo Truda, Workers' Cause'' journal began to develop the Platformism, platformist tendency, calling for the construction of a tightly coordinated anarchist organization, which was supported chiefly by Peter Arshinov and Nestor Makhno. This platform was criticized as authoritarian by a number of dissenting voices, including Voline, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer. Arshinov and Makhno's short-tempered response to these criticisms drew the eyre of other Russian exiles such as Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, who denounced them respectively as a "Bolshevik" and a "militarist", while also expressing a distaste with Fleshin and Steimer's factionalism.

During the late 1920s, a number of anarchist exiles decided to return to Russia and appealed to the Soviet government for permission. With the aid of the Right Oppositionist Nikolai Bukharin, Efim Iarchuk was permitted to return in 1925, after which he joined the Communist Party. In 1930, Arshniov also returned to Russia under amnesty and joined the Communist Party, leaving ''Dielo Truda'' in the editorial hands of Grigorii Maksimov. Under Maksimov, the publication took on a notable syndicalist stance while also offering a platform to other anarchist tendencies, becoming the Russian anarchist exiles' most important publication. Maksimov attempted to bridge the divide between the anarcho-syndicalists and anarcho-communists, publishing a

social credo

' that attempted to synthesise the two along the lines of

The Guillotine at Work

' and edited th

collected works

of Mikhail Bakunin. The remnants of the Russian anarchist exiles began to wane during the 1930s, as their journals became less frequent and filled with republications of old texts, their activities mostly consisted of celebrating the anniversaries of past events and their criticisms became increasingly levelled at Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. The events of the Spanish Revolution of 1936, Spanish Revolution briefly revived the exile movement, but after the defeat of the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, the exiles largely ceased activity. During this period a number of the exiled anarchist old guard began to die off, including Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman during the late 1930s, and Voline, Alexander Schapiro and Grigorii Maksimov in the wake of the Victory in Europe Day, Allied victory in World War II. The surviving Abba Gordin had since shifted away from communism, publishing a critique of Marxism in 1940 that concluded it was an ideology of "a privileged class of politico-economic organisateurs" rather than of workers, and further characterized the Russian Revolution as a "managerial revolution". Gordin increasingly gravitated towards nationalism, culminating in his adoption of Zionism and his eventual emigration to Israel, where he would die in 1964.

Following the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, establishment of the

Following the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, establishment of the  During the

During the  But despite the elimination of the anarchist old guard during the Purge, anarchist activity continued at a reduced scale. A new generation of anarchists emerged within the Gulags, with some participating in a 15-day hunger strike at the Penalty Isolator in Yaroslavl. Following the Allied victory in World War II, many POWs that were freed by the Red Army were subsequently met with deportation to Gulag camps in Siberia. There, a number of Marxist and anarchist POWs established the Democratic Movement of Northern Russia, which organized an uprising in 1947 that spread throughout several camps before being suppressed by the army. Anarchist tendencies subsequently spread throughout many of the Siberian camps, culminating in 1953 when the death of Stalin brought with it a wave of List of uprisings in the Gulag, uprisings, some of which included anarchist participation. The Norilsk uprising, in particular, saw the active participation of a number of Ukrainian Makhnovists.

But despite the elimination of the anarchist old guard during the Purge, anarchist activity continued at a reduced scale. A new generation of anarchists emerged within the Gulags, with some participating in a 15-day hunger strike at the Penalty Isolator in Yaroslavl. Following the Allied victory in World War II, many POWs that were freed by the Red Army were subsequently met with deportation to Gulag camps in Siberia. There, a number of Marxist and anarchist POWs established the Democratic Movement of Northern Russia, which organized an uprising in 1947 that spread throughout several camps before being suppressed by the army. Anarchist tendencies subsequently spread throughout many of the Siberian camps, culminating in 1953 when the death of Stalin brought with it a wave of List of uprisings in the Gulag, uprisings, some of which included anarchist participation. The Norilsk uprising, in particular, saw the active participation of a number of Ukrainian Makhnovists.

The power struggle that followed in the wake of Stalin's death ended with the consolidation of control by Nikita Khrushchev, who implemented a Khrushchev Thaw, reform program that relaxed Political repression in the Soviet Union, political repression and Censorship in the Soviet Union, censorship, released millions of political prisoners from the

The power struggle that followed in the wake of Stalin's death ended with the consolidation of control by Nikita Khrushchev, who implemented a Khrushchev Thaw, reform program that relaxed Political repression in the Soviet Union, political repression and Censorship in the Soviet Union, censorship, released millions of political prisoners from the

When Mikhail Gorbachev took over as List of leaders of the Soviet Union, leader of the Soviet Union, he implemented a set of reforms that included "Uskoreniye, acceleration", "Perestroika, restructuring", "Glasnost, transparency", "New political thinking, new thinking" and "Demokratizatsiya (Soviet Union), democratization". This provided the space for a new "informal" opposition movement to emerge onto the political scene with popular support, entryism, operating within official organizations in order to "turn the language of socialism, socialist ideology against the Soviet state", setting the groundwork for a resurgent anarchist movement. A number of "informal" libertarian Marxism, libertarian Marxists within the Moscow section of the Marxist Workers’ Party began publishing the ''Commune'' magazine, slowly gravitating towards

When Mikhail Gorbachev took over as List of leaders of the Soviet Union, leader of the Soviet Union, he implemented a set of reforms that included "Uskoreniye, acceleration", "Perestroika, restructuring", "Glasnost, transparency", "New political thinking, new thinking" and "Demokratizatsiya (Soviet Union), democratization". This provided the space for a new "informal" opposition movement to emerge onto the political scene with popular support, entryism, operating within official organizations in order to "turn the language of socialism, socialist ideology against the Soviet state", setting the groundwork for a resurgent anarchist movement. A number of "informal" libertarian Marxism, libertarian Marxists within the Moscow section of the Marxist Workers’ Party began publishing the ''Commune'' magazine, slowly gravitating towards

Black BlocA chronology of Russian anarchism

(1921–1953) from Libcom.org

Articles on Bolshevik repression of anarchists after 1917

from the Kate Sharpley Library

Interview with Mikhail Tsovma {{DEFAULTSORT:Russia, Anarchism in Anarchism in Russia, Anarchism by country, Russia Political history of Russia Political movements in Russia Political repression in the Soviet Union

Tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

and serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Through the history of radicalism during the early 19th-century, anarchism developed out of the populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

and nihilist movement

The Russian nihilist movementOccasionally, ''nihilism'' will be capitalized when referring to the Russian movement though this is not ubiquitous nor does it correspond with Russian usage. was a philosophical, cultural, and revolutionary movem ...

s' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

The first Russian to identify himself as an anarchist was the revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, who became a founding figure of the modern anarchist movement within the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

(IWA). In the context of the split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enterta ...

within the IWA between the Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectic ...

and the anarchists, the Russian Land and Liberty organization also split between a Marxist faction that supported political struggle and an anarchist faction that supported "propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

", the latter of which went on to orchestrate the assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

of Alexander II.

Specifically anarchist groups such as the Black Banner began to emerge at the turn of the 20th century, culminating with the anarchist participation in the Russian Revolutions of 1905

As the second year of the massive Russo-Japanese War begins, more than 100,000 die in the largest world battles of that era, and the war chaos leads to the 1905 Russian Revolution against Nicholas II of Russia (Shostakovich's 11th Symphony i ...

and 1917

Events

Below, the events of World War I have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 9 – WWI – Battle of Rafa: The last substantial Ottoman Army garrison on the Sinai Peninsula is captured by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's ...

. Though initially supportive of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, many anarchists turned against them in the wake of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

, launching a " Third Revolution" against the government with the intention of restoring soviet democracy

Soviet democracy, or council democracy, is a political system in which the rule of the population is exercised by directly elected ''soviets'' (Russian for "council"). The councils are directly responsible to their electors and bound by their ...

. But this attempted revolution was crushed by 1921, definitively ending with the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Locat ...

and the defeat of the Black Army in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

.

The anarchist movement lived on during the time of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in small pockets, largely within the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

where anarchist political prisoners were sent, but by the late 1930s its old guard had either fled into exile, died or disappeared during the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

. Following a number of uprisings in the wake of the death of Stalin, libertarian communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

began to reconstitute itself within the dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established Political system, political or Organized religion, religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and ...

human rights movement Human rights movement refers to a nongovernmental social movement engaged in activism related to the issues of human rights. The foundations of the global human rights movement involve resistance to: colonialism, imperialism, slavery, racism, segr ...

, and by the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, the anarchist movement had re-emerged onto the public sphere. In the modern day, anarchists make up a part of the opposition movement to the government of Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

.

History

Bakunin and the anarchists' exile

In 1848, on his return to

In 1848, on his return to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

published a fiery tirade against Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, which caused his expulsion from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. The revolutionary movement of 1848 gave him the opportunity to join a radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

*Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* Bl ...

of democratic agitation, and for his participation in the May Uprising in Dresden

The May Uprising took place in Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony in 1849; it was one of the last of the series of events known as the Revolutions of 1848.

Events leading to the May Uprising

In the German states, revolutions began in March 1848, start ...

of 1849 he was arrested and condemned to death. The death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, however, was commuted to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes for ...

, and he was eventually handed over to the Russian authorities, by whom he was imprisoned and finally sent to Eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

in 1857.

Bakunin received permission to move to the Amur

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

region, where he started collaborating with his relative General Count Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky

Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Muravyov-Amursky (also spelled as Nikolai Nikolaevich Muraviev-Amurskiy; russian: link=no, Никола́й Никола́евич Муравьёв-Аму́рский; – ) was a Russian general, statesman and diplomat, ...

, who had been Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Eastern Siberia for ten years. When Muravyov was removed from his position, Bakunin lost his stipend. He succeeded in escaping, probably with the collusion of the authorities and made his way through Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1861. He spent the rest of his life in exile in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, principally in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

In January 1869,

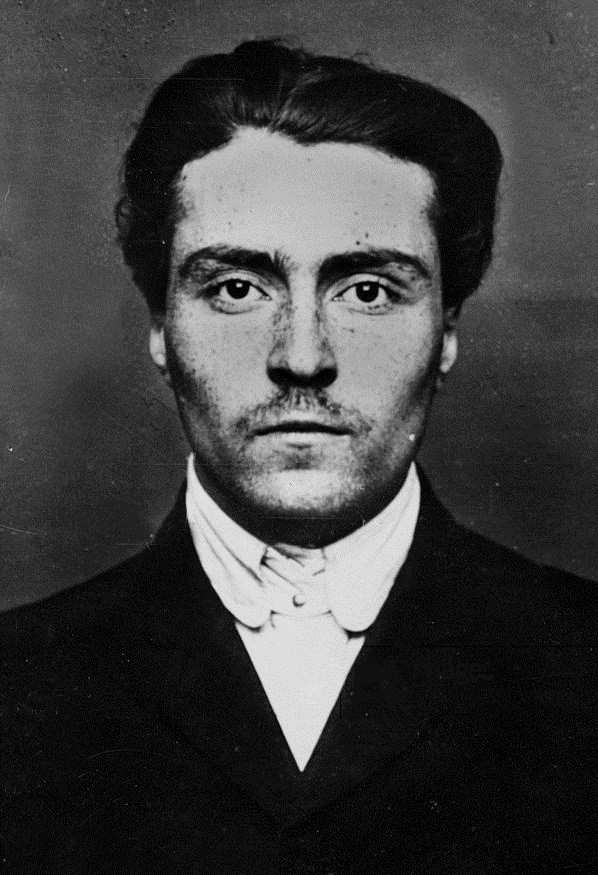

In January 1869, Sergey Nechayev

Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev (russian: Серге́й Генна́диевич Неча́ев) ( – ) was a Russian communist revolutionary and prominent figure of the Russian nihilist movement, known for his single-minded pursuit of revolution ...

spread false rumors of his arrest in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, then left for Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

before heading abroad. In Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, he pretended to be a representative of a revolutionary committee who had fled from the Peter and Paul Fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920s i ...

, and he won the confidence of revolutionary-in-exile Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

and his friend Nikolay Ogarev

Nikolay Platonovich Ogarev (Ogaryov; ; – ) was a Russian poet, historian and political activist. He was deeply critical of the limitations of the Emancipation reform of 1861 claiming that the serfs were not free but had simply exchanged one f ...

.

Bakunin played a prominent part in developing and elaborating the theory of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

and in leading the anarchist movement. He left a deep imprint on the movement of the Russian "revolutionary commoners" of the 1870s.

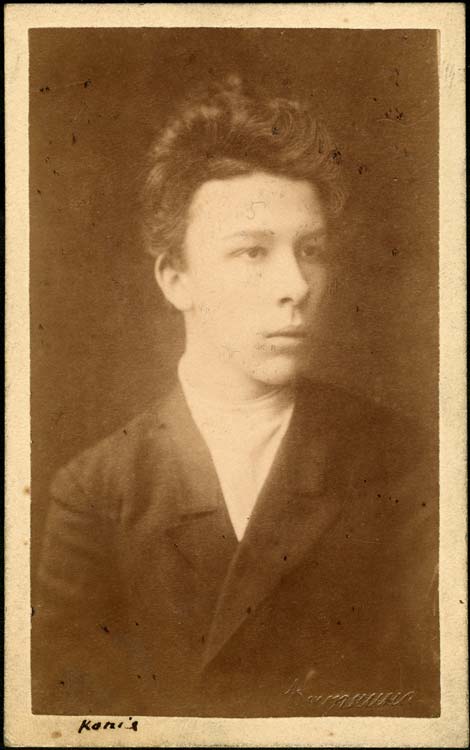

In 1873, Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

was arrested and imprisoned, but escaped in 1876 and went to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, moving after a short stay to Switzerland, where he joined the Jura Federation

The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who shared anti- ...

. In 1877 he went to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he helped to start the anarchist movement there. He returned to Switzerland in 1878, where he edited a revolutionary newspaper for the Jura Federation called ''Le Révolté'', subsequently also publishing various revolutionary pamphlets.

Nihilist movement

After an assassination attempt, Count

After an assassination attempt, Count Mikhail Tarielovich Loris-Melikov

Count Mikhail Tarielovich Loris-Melikov (, hy, Միքայել Լորիս-Մելիքյան; – 24 December 1888) was a Russian-Armenian statesman, General of the Cavalry, and Adjutant General of H. I. M. Retinue.

The Princes of Lori - Loris-M ...

was appointed the head of the Supreme Executive Commission and given extraordinary powers to fight the revolutionaries. Loris-Melikov's proposals called for some form of parliamentary body, and the Emperor Alexander II seemed to agree; these plans were never realized as of March 13 (March 1 Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

), 1881, Alexander was assassinated: while driving on one of the central streets of St. Petersburg, near the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

, he was mortally wounded by hand-made grenades and died a few hours afterwards. The conspirators Nikolai Kibalchich

Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich (russian: Николай Иванович Кибальчич, uk, Микола Іванович Кибальчич, sr, Никола Кибалчић, ''Mykola Ivanovych Kybalchych''; 19 October 1853 – April 3, 188 ...

, Sophia Perovskaya

Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya (russian: Со́фья Льво́вна Перо́вская; – ) was a Russian Empire revolutionary and a member of the revolutionary organization ''Narodnaya Volya''. She helped orchestrate the assassination of ...

, Nikolai Rysakov

Nikolai Ivanovich Rysakov (russian: Николай Иванов Рысаков; – 15 April 1881) was a Russian revolutionary and a member of Narodnaya Volya. He personally took part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia. He threw ...

, Timofey Mikhailov

Timofey Mikhailovich Mikhailov (russian: Тимофе́й Михайлович Мих́айлов; — 15 April 1881) was a member of the Russian revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya. He was designated a bomb-thrower in the assassination of ...

, and Andrei Zhelyabov

Andrei Ivanovich Zhelyabov (russian: Желябов, Андрей Иванович; – ) was a Russian Empire revolutionary and member of the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya.

After graduating from a gymnasium in Kerch in 1869, Zhelyab ...

were all arrested and sentenced to death. Hesya Helfman

Hesya Mirovna (Meerovna) Helfman (, ) 1855, Mazyr — 1 ( N.S. 13) February 1882, Saint Petersburg), was a Russian revolutionary member of ''Narodnaya Volya'', who was implicated in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II.

Biography Early life

...

was sent to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. The assassin was identified as Ignacy Hryniewiecki

Ignacy Hryniewiecki or Ignaty Ioakhimovich Grinevitsky). (russian: Игнатий Гриневицкий, pl, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, be, Ігнат Грынявіцкі; — March 13, 1881) was a Polish member of the Russian revolutionary societ ...

(Ignatei Grinevitski), who died during the attack.

Tolstoyan movement

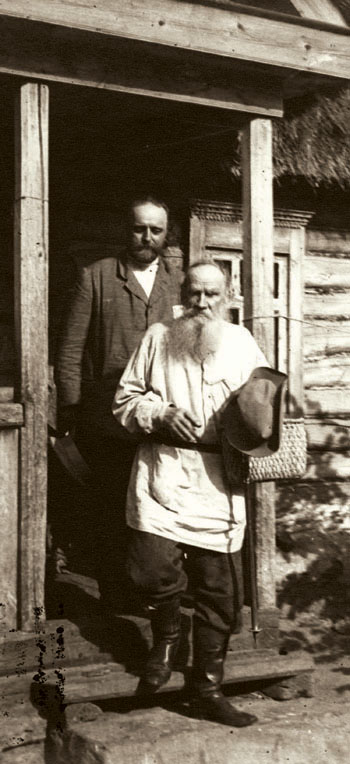

Although he did not call himself an anarchist,Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

(1828-1910) in his later writings formulated a philosophy that amounted to advocating resistance to the state, and influenced the worldwide development of anarchism as well as pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

worldwide. In a series of books and articles, including ''What I Believe'' (1884) (russian: В чём моя вера?) and ''Christianity and Patriotism'' (1894), (russian: Христианство и патриотизм) Tolstoy used the Christian gospels as a starting-point for an ideology that held violence as the ultimate evil.

Tolstoy professed contempt for the private ownership of land, but his anarchism lay primarily in his view that the state exists essentially as an instrument of compulsory force, which he considered the antithesis of all religious teachings. He once wrote, "A man who unconditionally promises in advance to submit to laws which are made and will be made by men, by this very promise renounces Christianity."

In the 1880s Tolstoy's pacifist anarchism gained a following in Russia. In the following decades the Tolstoyan movement

The Tolstoyan movement is a social movement based on the philosophical and religious views of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910). Tolstoy's views were formed by rigorous study of the ministry of Jesus, particularly the Sermon on the Mo ...

, which Tolstoy himself had not expected or encouraged, spread through Russia and to other countries. Resistance to war had particular meaning in Russia since Emperor Alexander II had implemented compulsory military service in 1874. From the 1880s into the early 20th century, an increasing number of young men refused military service on the basis of a Tolstoyan moral objection to war. Such actions moved Tolstoy, and he often participated in the defense of peaceful objectors in court.

Many people inspired by Tolstoy's version of Christian morality set up agricultural communes in various parts of Russia, pooling their income and producing their own food, shelter and goods. Tolstoy appreciated such efforts but sometimes criticized these groups for isolating themselves from the rest of the country, feeling that the communes did little to contribute to a worldwide peace movement.

Although Tolstoy's actions frequently diverged from the ideals he set for himself (for example, he owned a large estate), his followers continued to promote the Tolstoyan vision of world peace well after his death in 1910.

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

was one of the three categories of anarchism in Russia, along with the more prominent anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

and anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

. The ranks of the Russian individualist anarchists were predominantly drawn from the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

and the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

. For anarchist historian Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 1961 ...

"The two leading exponents of individualist anarchism, both based in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, were Aleksei Alekseevich Borovoi and Lev Chernyi

Lev Chernyi ( rus, Лев Чёрный, p=ˈlʲef ˈtɕɵrnɨj, a=Lyev Chyornyy.ru.vorb.oga; born Pavel Dimitrievich Turchaninov, rus, Па́вел Дми́триевич Турчани́нов, p=ˈpavʲɪl ˈdmʲitrʲɪjɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrtɕɪˈn ...

(Pavel Dmitrievich Turchaninov). From Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, Prose poetry, prose poet, cultural critic, Philology, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philo ...

, they inherited the desire for a complete overturn of all values accepted by bourgeois societypolitical, moral, and cultural. Furthermore, strongly influenced by Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

and Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

, the German and American theorists of individualist anarchism, they demanded the total liberation of the human personality from the fetters of organized society."

Some Russian individualists anarchists "found the ultimate expression of their social alienation in violence and crime, others attached themselves to avant-garde literary and artistic circles, but the majority remained "philosophical" anarchists who conducted animated parlor discussions and elaborated their individualist theories in ponderous journals and books."

Lev Chernyi

Lev Chernyi ( rus, Лев Чёрный, p=ˈlʲef ˈtɕɵrnɨj, a=Lyev Chyornyy.ru.vorb.oga; born Pavel Dimitrievich Turchaninov, rus, Па́вел Дми́триевич Турчани́нов, p=ˈpavʲɪl ˈdmʲitrʲɪjɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrtɕɪˈn ...

was an important individualist anarchist involved in resistance against the rise to power of the Bolshevik Party. He adhered mainly to Stirner and the ideas of Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

. In 1907, he published a book entitled ''Associational Anarchism'', in which he advocated the "free association of independent individuals.". On his return from Siberia in 1917 he enjoyed great popularity among Moscow workers as a lecturer. Chernyi was also Secretary of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups

The Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups (MFAG) was a network of anarchist groups established in Moscow in 1917. They occupied the Merchants' House shortly after the February Revolution. They published ''Anarkhiia'', weekly after its launch in S ...

, which was formed in March 1917. He was an advocate "for the seizure of private homes", which was an activity seen by the anarchists after the October revolution as direct expropriation on the bourgoise. He died after being accused of participation in an episode in which this group bombed the headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party. Although most likely not being really involved in the bombing, he might have died of torture.

Chernyi advocated a Nietzschean

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed his philosophy during the late 19th century. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Arthur Schopenhauer's ''Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung'' (''The World as Will and Repres ...

overthrow of the values of bourgeois Russian society, and rejected the voluntary communes

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious, ...

of anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

as a threat to the freedom of the individual. Scholars including Avrich and Allan Antliff have interpreted this vision of society to have been greatly influenced by the individualist anarchists

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relia ...

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

, and Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

. Subsequent to the book's publication, Chernyi was imprisoned in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

under the Russian Czarist

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

regime for his revolutionary activities.

On the other hand, Alexei Borovoi (1876?-1936),http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=labadie;cc=labadie;view=toc;idno=2917084.0001.001 "Anarchism and Law." on Anarchism Pamphlets in the Labadie Collection was a professor of philosophy at Moscow University, "a gifted orator and the author of numerous books, pamphlets, and articles which attempted to reconcile individualist anarchism with the doctrines of syndicallism". He wrote among other theoretical works, ''Anarkhizm'' in 1918 just after the October revolution and ''Anarchism and Law''.

The Doukhobors

The origin of the Doukhobors dates back to 16th- and 17th-century Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy. The Doukhobors ("Spirit Wrestlers") are a radical Christianity, Christian sect who maintained a belief in

The origin of the Doukhobors dates back to 16th- and 17th-century Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy. The Doukhobors ("Spirit Wrestlers") are a radical Christianity, Christian sect who maintained a belief in pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

and a communal lifestyle while rejecting secular government. In 1899, the most zealous third (about 7,400) Doukhobors fled repression in Russian Empire, Imperial Russia and migrated to Canada, mostly in the provinces of Saskatchewan and British Columbia. The funds for the trip were paid for by the Quakers, Religious Society of Friends and the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. Peter Kropotkin suggested Canada to Tolstoy as a safe-haven for the Doukhobors because while on a speaking tour across Canada, Kropotkin observed the religious tolerance experienced by the Mennonites.

Revolution of 1905

The first anarchist groups to attract a significant following of Russian workers or peasants, were the

The first anarchist groups to attract a significant following of Russian workers or peasants, were the anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

Chernoe Znamia, Chernoe-Znamia groups, founded in Białystok in 1903. They drew their support mainly from the impoverished and persecuted working-class Jews of the "Pale of Settlement, Pale"-the places on the Western borders of the Russian Empire where Jews were "allowed" to live. The Chernoe Znamia made their first attack in 1904, when Nisan Farber, a devoted member of the group, stabbed a strike-breaking industrialist on the Jewish Day of Atonement. The Chernoe Znamia, Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Left SRs and Zionism, Zionists of Bialystock congregated inside a forest to decide their next action. At the end of the meeting the shouts of "Long Live the Social Revolution" and "Hail Anarchy" attracted the police to the secret meeting. Violence ensued, leaving many revolutionaries arrested or wounded. In vengeance, Nisan Farber threw a homemade bomb at a police station, killing himself and injuring many. He quickly became a Revolutionary Martyr to the Anarchists, and when Bloody Sunday (1905), Bloody Sunday broke out in ST Petersburg his actions began to be imitated by the rest of the Chernoe Znamias. Obtaining weapons was the first objective. Police stations, gun shops and arsenals were raided and their stock stolen. Bomb labs were set up and money gleaned from expropriations went to buying more weapons from Vienna. Bialystock became a warzone, virtually everyday an Anarchist attack or a Police repression. Dnipro, Ekaterinoslav, Odessa, Warsaw and Baku all became witnesses to more and more gunpoint hold-ups and tense shootouts. Sticks of dynamite were thrown into factories or mansions of the most loathed capitalists. Workers were encouraged to overthrow their bosses and manage the factory for themselves. Workers and peasants throughout the Empire took this advice to heart and sporadic uprisings in the remote countryside became a common sight. The Western borderlands in particular - the cities of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania flared up in anger and hatred.

The Revolution in the Pale reached a bloody climax in November and December 1905 with the bombing of the Hotel Bristol in Warsaw and the Cafe Libman in Odessa. After the suppression of the December Uprising in Moscow, the Anarchists retreated for a while, but soon returned to the Revolution. Even the small towns and villages of the countryside had their own Anarchist fighting groups. But the tide was turning against the revolutionaries. In 1907, the Tsarist Minister Pyotr Stolypin, Stolypin set about his new "pacification" program. Police received more arms, orders and reinforcements to raid Anarchist centres. The police would track the Anarchists to their headquarters and then strike swiftly and brutally. The Anarchists were tried by court martial in which preliminary investigation was waived, verdicts delivered within 2 days and sentences executed immediately. Rather than succumb to the ignominy of arrest, many Anarchists preferred suicide when cornered. Those that were caught would usually deliver a rousing speech on Justice and Anarchy before they were executed, in the manner of Ravachol and Émile Henry (anarchist), Émile Henry. By 1909 most of the Anarchists were either dead, exiled or in jail. Anarchism was not to resurface in Russia until 1917.

February Revolution

In 1917, Peter Kropotkin returned to Saint Petersburg, Petrograd, where he helped Alexander Kerensky's Russian Provisional Government to formulate policies. He curtailed his activity when theBolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

came to power.

Following the abdication of Nicholas II of Russia, Czar Nicholas II in February 1917 and the subsequent creation of a Provisional Government, many Russian anarchists joined the Bolsheviks in campaigning for further revolution. Since the repression after the 1905 Russian Revolution, Revolution of 1905, new anarchist organizations had been slowly and quietly growing in Russia, and in 1917 saw a new opportunity to end state power.

Though within the next year they would come to consider the Bolsheviks traitors to the socialist cause, urban anarchist groups initially saw Lenin and his comrades as allies in the fight against capitalist oppression. Understanding the need for widespread support in his quest for Communism, Lenin often deliberately appealed to anarchist sentiments in the eight months between the February and October Revolutions. Many optimistic anarchists interpreted Lenin's slogan of “All Power to the Soviets!” as the potential for a Russia run by autonomous collectives without the burden of central authority. Lenin also described the triumph of Communism as the eventual “withering away of the state.”

All this time, however, anarchists remained wary of the Bolsheviks. Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, the hero of Russian anarchism, had expressed skepticism toward the scientific, excessively rational nature of Marxism. He and his followers preferred a more instinctive form of revolution. One of them, Bill Shatov, described the anarchists as “the romanticists of the Revolution.” Their eagerness to get the ball rolling became apparent during the July Days, in which Petrograd soldiers, sailors and workers revolted in an attempt to claim power for the Petrograd Soviet. While this was not an anarchist-driven event, the anarchists of Petrograd played a large role in inciting the people of the city to action. In any case, Lenin was not amused by the revolt and instructed those involved to quiet down until he told them otherwise.

In spite of some tension between the groups, the anarchists remained largely supportive of Lenin right up to the October Revolution. Several anarchists participated in the overthrow of the Provisional Government, and even the Military Revolutionary Committee that orchestrated the coup.

October Revolution

At first it seemed to some Anarchists the revolution could inaugurate the stateless society they had long dreamed of. On these terms, some Bolshevik-Anarchist alliances were made. In Moscow, the most perilous and critical tasks during the October Revolution fell upon the Anarchist Regiment, led by the old libertarians and it was they who dislodged the Whites from the Kremlin, the Metropole and other defenses. and it was the Anarchist sailor who led the attack on the Constituent Assembly in October 1917. For a while, the Anarchists rejoiced, elated at the thought of the new age that Russia had won. Bolshevik-anarchist relations soon turned sour as the various anarchist groups realized that the Bolsheviks were not interested in pluralism, but rather a centralized one-party rule. A few prominent anarchist figures such as Bill Shatov and Yuda Roshchin, despite their disappointment, encouraged anarchists to cooperate with the Bolsheviks in the present conflict with the hope that there would be time to negotiate. But most anarchists became disillusioned quite quickly with their supposed Bolshevik allies, who took over the soviets and placed them under Communist control. The sense of betrayal came to a head in March 1918, when Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany. Though the Bolshevik leaders claimed that the treaty was necessary to allow the revolution to progress, anarchists widely saw it as an excessive compromise which counteracted the idea of international revolution. After months of increasing anarchist resistance and dwindling Bolshevik patience, the Communist government decisively split with their libertarian agitators in the spring of 1918. In Moscow and Petrograd the newly formed Cheka was sent in to disband all anarchist organizations, and largely succeeded. On the night of April 12, 1918, the Cheka raided 26 anarchist centres inMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, including the Lenkom Theatre#House of Anarchy, House of Anarchy, the headquarters of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups. A fierce battle raged on Malaia Dimitrovka Street. About 40 anarchists were killed or wounded, and approximately 500 were imprisoned. A dozen Cheka agents had also been killed in the fighting. Anarchists joined Mensheviks and Left Socialist revolutionaries in boycotting the 1918 May Day celebrations.

By this time some belligerent anarchist dissenters armed themselves and formed groups of so-called “Black Guards” that continued to fight Communist power on a small scale as the Civil War began. The urban anarchist movement, however, was dead.

Civil War

The anthropologist Eric Wolf asserts that peasants in rebellion are "natural" anarchists. After initially looking favorably upon the Bolsheviks for their proposed land reforms, by 1918 peasants largely came to despise the new government as it became increasingly centralized and exploitative in its dealings with the rural population. Marxist-Leninists had never given the peasants great credit, and with the Civil War against the White movement, White Armies underway, the Red Army primarily used peasant villages as suppliers of grain, which it “requisitioned,” or in other words, seized by force.Vladimir N. Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: Political Parties and Social Movements in Russia, 1918-1922. Princeton, 1994, p. 127-62, 300.

Abused equally by the Red and invading White armies, large groups of peasants, as well as Red Army deserters, formed “Green” armies that resisted the Reds and Whites alike. These forces had no grand political agenda like their enemies, for the most part they simply wanted to stop being harassed and be allowed to govern themselves. Though the Green Armies have largely been ignored by history (and by Soviet historians in particular), they constituted a formidable force and a major threat to Red victory in the Civil War. Even after the party declared the Civil War over in 1920, the Red-Green war persisted for some time.

Red Army generals noted that in many regions peasant rebellions were heavily influenced by anarchist leaders and ideas. In Ukraine, the most notorious peasant rebel leader was an anarchist general named Nestor Makhno. Makhno had originally led his forces in collaboration with the Red Army against the Whites. In the region of Ukraine where his forces were stationed, Makhno oversaw the development of an autonomous system of government based on the productive coordination of communes. According to Peter Marshall, a historian of anarchism, "For more than a year, anarchists were in charge of a large territory, one of the few examples of anarchy in action on a large scale in modern history.

Unsurprisingly, the Bolsheviks came to see Makhno's experiment in self-government as a threat in need of elimination, and in 1920 the Red Army sought to take control of Makhno's forces. They resisted, but the officers (not including Makhno himself) were arrested and executed by the end of 1920. Makhno continued to fight before going into exile in Paris the next year.

The anthropologist Eric Wolf asserts that peasants in rebellion are "natural" anarchists. After initially looking favorably upon the Bolsheviks for their proposed land reforms, by 1918 peasants largely came to despise the new government as it became increasingly centralized and exploitative in its dealings with the rural population. Marxist-Leninists had never given the peasants great credit, and with the Civil War against the White movement, White Armies underway, the Red Army primarily used peasant villages as suppliers of grain, which it “requisitioned,” or in other words, seized by force.Vladimir N. Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: Political Parties and Social Movements in Russia, 1918-1922. Princeton, 1994, p. 127-62, 300.

Abused equally by the Red and invading White armies, large groups of peasants, as well as Red Army deserters, formed “Green” armies that resisted the Reds and Whites alike. These forces had no grand political agenda like their enemies, for the most part they simply wanted to stop being harassed and be allowed to govern themselves. Though the Green Armies have largely been ignored by history (and by Soviet historians in particular), they constituted a formidable force and a major threat to Red victory in the Civil War. Even after the party declared the Civil War over in 1920, the Red-Green war persisted for some time.

Red Army generals noted that in many regions peasant rebellions were heavily influenced by anarchist leaders and ideas. In Ukraine, the most notorious peasant rebel leader was an anarchist general named Nestor Makhno. Makhno had originally led his forces in collaboration with the Red Army against the Whites. In the region of Ukraine where his forces were stationed, Makhno oversaw the development of an autonomous system of government based on the productive coordination of communes. According to Peter Marshall, a historian of anarchism, "For more than a year, anarchists were in charge of a large territory, one of the few examples of anarchy in action on a large scale in modern history.

Unsurprisingly, the Bolsheviks came to see Makhno's experiment in self-government as a threat in need of elimination, and in 1920 the Red Army sought to take control of Makhno's forces. They resisted, but the officers (not including Makhno himself) were arrested and executed by the end of 1920. Makhno continued to fight before going into exile in Paris the next year.

Third Russian Revolution

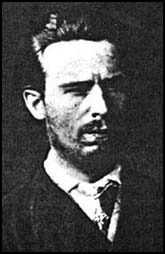

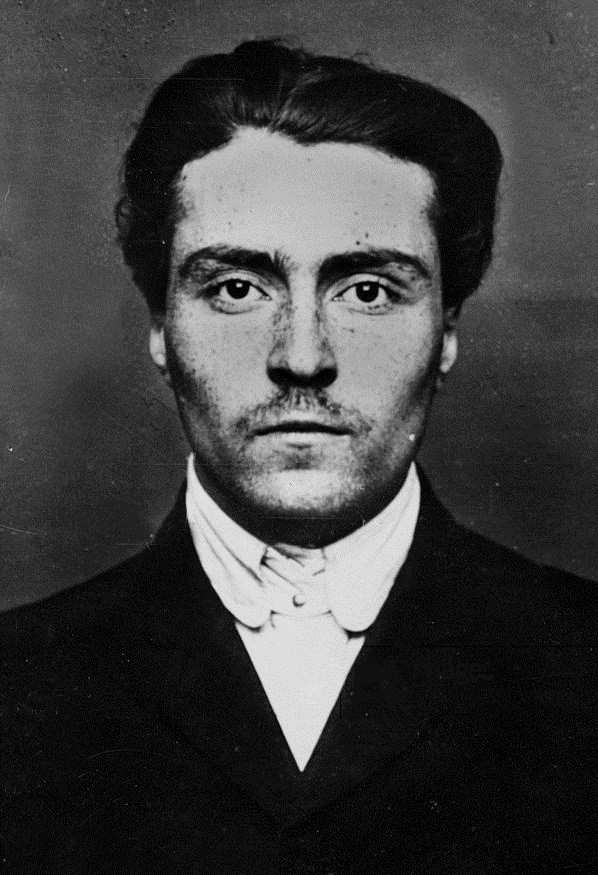

Lev Chernyi

Lev Chernyi ( rus, Лев Чёрный, p=ˈlʲef ˈtɕɵrnɨj, a=Lyev Chyornyy.ru.vorb.oga; born Pavel Dimitrievich Turchaninov, rus, Па́вел Дми́триевич Турчани́нов, p=ˈpavʲɪl ˈdmʲitrʲɪjɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrtɕɪˈn ...

and Fanya Baron were both Anarchists.

In exile

Following the suppression of the anarchist movement in Russia, a number of anarchists fled the country into exile, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Volin, Mark Mratchny, Grigorii Maksimov, Boris Yelensky, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer, who went on to establish relief organizations which provided aid for anarchist political prisoners back in Russia.

Following the suppression of the anarchist movement in Russia, a number of anarchists fled the country into exile, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Volin, Mark Mratchny, Grigorii Maksimov, Boris Yelensky, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer, who went on to establish relief organizations which provided aid for anarchist political prisoners back in Russia.

To the disillusioned Russian anarchist exiles, the experience of the Russian Revolution had fully justified Mikhail Bakunin's earlier declaration that "socialism without liberty is slavery and bestiality." Russian anarchists living abroad began to openly attack the "new kings" of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Communist Party, criticising the NEP as a restoration of capitalism and comparing Vladimir Lenin to the Spanish inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada, the Italian political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre. They positioned themselves in opposition to the Bolshevik government, calling for the destruction of Russian state capitalism and its replacement with workers' self-management by factory committees and workers' council, councils. But while anarchist exiles were united in their criticisms of the Bolshevik government and their recognition that the Russian anarchist movement had collapsed due to its disorganization, their internal divisions remained, with the Anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalists around Grigorii Maksimov, Efim Iarchuk and Alexander Schapiro establishing ''The Workers' Way'' as their organ, while anarcho-communism, anarcho-communists around Peter Arshinov and Volin established ''The Anarchist Herald'' as their own.

The anarcho-syndicalists looked to remedy the issue of anarchist disorganization through the foundation of a new international organization, culminating in the establishment of the IWA–AIT, International Workers' Association (IWA) in December 1922. The IWA analyzed the events of the Russian Revolution as having been a project to build state socialism rather than revolutionary socialism, called for the construction of trade unions to win short-term gains while building towards a general strike and declared their goal to be a social revolution that would abolish centralized states and replace them with a network of workers' councils. Maxmioff later moved to the