Rugby School on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rugby School is a public school (English

BBC. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

Rugby School was founded in 1567 as a provision in the will of Lawrence Sheriff, who had made his fortune supplying groceries to Queen

Rugby School was founded in 1567 as a provision in the will of Lawrence Sheriff, who had made his fortune supplying groceries to Queen

The game of

The game of

Rugby Fives is a handball game, similar to squash, played in an enclosed court. It has similarities with Winchester Fives (a form of Wessex Fives) and Eton Fives.

It is most commonly believed to be derived from Wessex Fives, a game played by Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, who had played Wessex Fives when a boy at Lord Weymouth's Grammar, now Warminster School. The open court of Wessex Fives, built in 1787, is still in existence at Warminster School although it has fallen out of regular use.

Rugby Fives is played between two players (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles), the aim being to hit the ball above a 'bar' across the front wall in such a way that the opposition cannot return it before a second bounce. The ball is slightly larger than a golf ball, leather-coated and hard. Players wear leather padded gloves on both hands, with which they hit the ball.

Rugby Fives continues to have a good following with tournaments being run nationwide, presided over by the Rugby Fives Association.

Rugby Fives is a handball game, similar to squash, played in an enclosed court. It has similarities with Winchester Fives (a form of Wessex Fives) and Eton Fives.

It is most commonly believed to be derived from Wessex Fives, a game played by Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, who had played Wessex Fives when a boy at Lord Weymouth's Grammar, now Warminster School. The open court of Wessex Fives, built in 1787, is still in existence at Warminster School although it has fallen out of regular use.

Rugby Fives is played between two players (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles), the aim being to hit the ball above a 'bar' across the front wall in such a way that the opposition cannot return it before a second bounce. The ball is slightly larger than a golf ball, leather-coated and hard. Players wear leather padded gloves on both hands, with which they hit the ball.

Rugby Fives continues to have a good following with tournaments being run nationwide, presided over by the Rugby Fives Association.

The school has produced a number of cricketers who have gone onto play Test and

The school has produced a number of cricketers who have gone onto play Test and

There have been a number of notable Old Rugbeians including the purported father of the sport of Rugby William Webb Ellis, the inventor of Australian rules football Tom Wills, the war poets Rupert Brooke and John Gillespie Magee, Jr., Prime Minister

There have been a number of notable Old Rugbeians including the purported father of the sport of Rugby William Webb Ellis, the inventor of Australian rules football Tom Wills, the war poets Rupert Brooke and John Gillespie Magee, Jr., Prime Minister

School House, Rugby School 10.21.jpg, The School House, of 1813

Rugby School buildings from Warwick Street 9.21 (2).JPG, From left to right; New Quad Buildings, Chapel and War Memorial Chapel.

online

* Hope-Simpson, John Barclay. ''Rugby Since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842.'' (1967). * Mack, Edward Clarence. ''Public schools and British opinion, 1780 to 1860: An examination of the relationship between contemporary ideas and the evolution of an English institution'' (1938), comparison with other elite schools * Neddam*, Fabrice. "Constructing masculinities under Thomas Arnold of Rugby (1828–1842): gender, educational policy and school life in an early‐Victorian public school." ''Gender and Education'' 16.3 (2004): 303–326. * Rouse, W.H.D. ''A history of Rugby School'' (1898

online

independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school, ...

for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up to 1667, the school remained in comparative obscurity. Its re-establishment by Thomas Arnold during his time as Headmaster, from 1828 to 1841, was seen as the forerunner of the Victorian public school. It was one of nine prestigious schools investigated by the Clarendon Commission of 1864 and later regulated as one of the seven schools included in the Public Schools Act 1868.

The school's alumni – or " Old Rugbeians" – include a UK prime minister, several bishops, prominent poets, scientists, writers and soldiers.

Rugby School is the birthplace of rugby football

Rugby football is the collective name for the team sports of rugby union and rugby league.

Canadian football and, to a lesser extent, American football were once considered forms of rugby football, but are seldom now referred to as such. The ...

."Six ways the town of Rugby helped change the world"BBC. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

History

Rugby School was founded in 1567 as a provision in the will of Lawrence Sheriff, who had made his fortune supplying groceries to Queen

Rugby School was founded in 1567 as a provision in the will of Lawrence Sheriff, who had made his fortune supplying groceries to Queen Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

. Since Lawrence Sheriff lived in Rugby and the neighbouring Brownsover, the school was intended to be a free grammar school for the boys of those towns. Up to 1667, the school remained in comparative obscurity. Its history during that trying period is characterised mainly by a series of lawsuits between the Howkins family (descendants of the founder's sister), who tried to defeat the intentions of the testator, and the masters and trustees, who tried to carry them out. A final decision was handed down in 1667, confirming the findings of a commission in favour of the trust, and henceforth the school maintained a steady growth. "Floreat Rugbeia" is the traditional school song.

In 1845, a committee of Rugby schoolboys, William Delafield Arnold, W. W. Shirley and Frederick Hutchins, wrote the "Laws of Football as Played At Rugby School", the first published set of laws for any code of football.

It was no longer desirable to have only local boys attending and the nature of the school shifted, and so a new school – Lawrence Sheriff Grammar School – was founded in 1878 to continue Lawrence Sheriff's original intentions; that school receives a substantial proportion of the endowment income from Lawrence Sheriff's estate every year.

Rugby was one of the nine prestigious schools investigated by the Clarendon Commission of 1861–64 (the schools under scrutiny being Eton, Charterhouse, Harrow

Harrow may refer to:

Places

* Harrow, Victoria, Australia

* Harrow, Ontario, Canada

* The Harrow, County Wexford, a village in Ireland

* London Borough of Harrow, England

** Harrow, London, a town in London

** Harrow (UK Parliament constituency)

...

, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'S ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buck ...

, and Winchester, and two day schools: St Paul's and Merchant Taylors). Rugby went on to be included in the Public Schools Act 1868, which ultimately related only to the seven boarding schools.

The core of the school (which contains School House, featured in '' Tom Brown's Schooldays'') was completed in 1815 and is built around the Old Quad (quadrangle), with its Georgian architecture. Especially notable rooms are the Upper Bench (an intimate space with a book-lined gallery), the Old Hall of School House, and the Old Big School (which makes up one side of the quadrangle and was once the location for teaching all junior pupils). Thomas Hughes (like his fictional hero, Tom Brown) once carved his name on the hands of the school clock, situated on a tower above the Old Quad. The polychromatic school chapel, new quadrangle, Temple Reading Room, Macready Theatre and Gymnasium were designed by well-known Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

Gothic revival architect William Butterfield in 1875, and the smaller Memorial Chapel was dedicated in 1922.

The Temple Speech Room, named after former headmaster and Archbishop of Canterbury Frederick Temple (1858–69) is now used for whole-School assemblies, speech days, concerts, musicals – and BBC ''Mastermind''. Oak-panelled walls boast the portraits of illustrious alumni, including Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasem ...

holding his piece of paper. Between the World Wars, the Memorial Chapel, the Music Schools and a new Sanatorium appeared.

In 1975 two girls were admitted to the sixth form, and the first girls’ house opened three years later, followed by three more. In 1992, the first 13-year-old girls arrived, and in 1995 Rugby had its first-ever Head Girl, Louise Woolcock, who appeared on the front page of ''The Times''. In September 2003 the last girls’ house was added. Today, total enrolment of day pupils, from forms 4 to 12, numbers around 800.

Rugby football

The game of

The game of Rugby football

Rugby football is the collective name for the team sports of rugby union and rugby league.

Canadian football and, to a lesser extent, American football were once considered forms of rugby football, but are seldom now referred to as such. The ...

owes its name to the school.

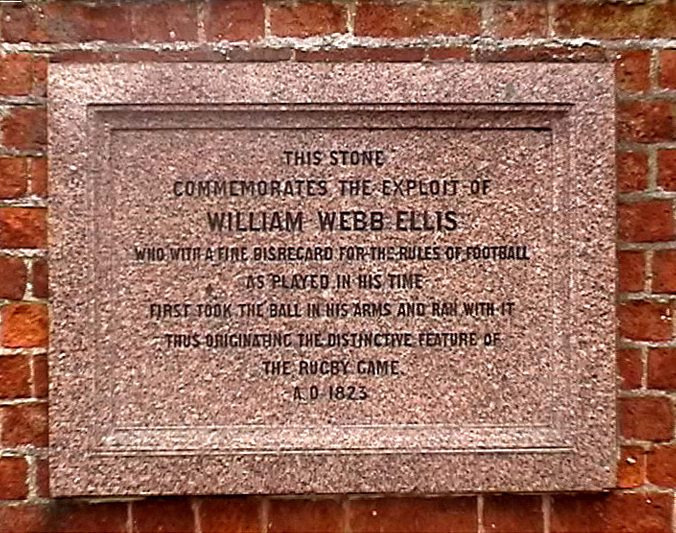

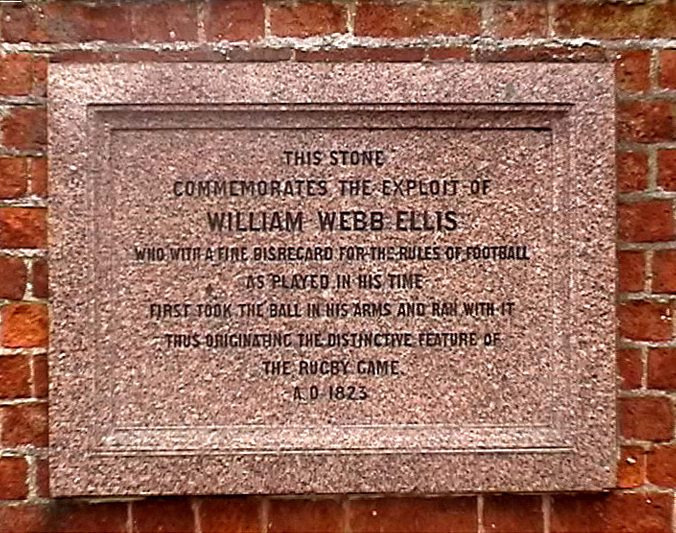

The legend of William Webb Ellis and the origin of the game is commemorated by a plaque. The story is that Webb Ellis was the first to pick up a football and run with it, and thus invent a new sport. However, the sole source of the story is Matthew Bloxam, a former pupil but not a contemporary of Webb Ellis. In October 1876, four years after the death of Webb Ellis, in a letter to the school newspaper ''The Meteor'' he quotes an unknown friend relating the story to him. He elaborated on the story four years later in another letter to ''The Meteor'', but shed no further light on its source. Richard Lindon, a boot and shoemaker who had premises across the street from the School's main entrance in Lawrence Sheriff Street, is credited with the invention of the "oval" rugby ball, the rubber inflatable bladder and the brass hand pump.

There were no standard rules for football in Webb Ellis's time at Rugby (1816–1825) and most varieties involved carrying the ball. The games played at Rugby were organised by the pupils and not the masters, the rules being a matter of custom and not written down. They were frequently changed and modified with each new intake of students.

Rugby Fives

Rugby Fives is a handball game, similar to squash, played in an enclosed court. It has similarities with Winchester Fives (a form of Wessex Fives) and Eton Fives.

It is most commonly believed to be derived from Wessex Fives, a game played by Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, who had played Wessex Fives when a boy at Lord Weymouth's Grammar, now Warminster School. The open court of Wessex Fives, built in 1787, is still in existence at Warminster School although it has fallen out of regular use.

Rugby Fives is played between two players (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles), the aim being to hit the ball above a 'bar' across the front wall in such a way that the opposition cannot return it before a second bounce. The ball is slightly larger than a golf ball, leather-coated and hard. Players wear leather padded gloves on both hands, with which they hit the ball.

Rugby Fives continues to have a good following with tournaments being run nationwide, presided over by the Rugby Fives Association.

Rugby Fives is a handball game, similar to squash, played in an enclosed court. It has similarities with Winchester Fives (a form of Wessex Fives) and Eton Fives.

It is most commonly believed to be derived from Wessex Fives, a game played by Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, who had played Wessex Fives when a boy at Lord Weymouth's Grammar, now Warminster School. The open court of Wessex Fives, built in 1787, is still in existence at Warminster School although it has fallen out of regular use.

Rugby Fives is played between two players (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles), the aim being to hit the ball above a 'bar' across the front wall in such a way that the opposition cannot return it before a second bounce. The ball is slightly larger than a golf ball, leather-coated and hard. Players wear leather padded gloves on both hands, with which they hit the ball.

Rugby Fives continues to have a good following with tournaments being run nationwide, presided over by the Rugby Fives Association.

Cricket

The school has produced a number of cricketers who have gone onto play Test and

The school has produced a number of cricketers who have gone onto play Test and first-class cricket

First-class cricket, along with List A cricket and Twenty20 cricket, is one of the highest-standard forms of cricket. A first-class match is one of three or more days' scheduled duration between two sides of eleven players each and is officia ...

. The school has played host to two major matches, the first of which was a Twenty20

Twenty20 (T20) is a shortened game format of cricket. At the professional level, it was introduced by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) in 2003 for the county cricket, inter-county competition. In a Twenty20 game, the two teams have ...

match between Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

and Glamorgan in the 2013 Friends Life t20. The second match was a List-A one-day match between Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

and Sussex in the 2015 Royal London One-Day Cup

The 2015 Royal London One-Day Cup tournament was the scheduled limited overs cricket competition for 2015 season of England and Wales first-class counties. It was won by Gloucestershire County Cricket Club, who defeated Surrey by the narrow marg ...

, though it was due to host a match in the 2014 competition, however this was abandoned. In the 2015 match, William Porterfield scored a century

A century is a period of 100 years. Centuries are numbered ordinally in English and many other languages. The word ''century'' comes from the Latin ''centum'', meaning ''one hundred''. ''Century'' is sometimes abbreviated as c.

A centennial ...

, with a score of exactly 100.

Houses

Rugby School has both day and boarding-pupils, the latter in the majority. Originally it was for boys only, but girls have been admitted to the sixth form since 1975. It went fully co-educational in 1992. The school community is divided into houses.Academic life

Pupils beginning Rugby in the F Block (first year) study various subjects. In a pupil's second year (E block), they do nine subjects which are for their GCSEs, this is the same for the D Block (GCSE year). The school then provides standard A-levels in 29 subjects. Students at this stage have the choice of taking three or four subjects and are also offered the opportunity to take an extended project.Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to d ...

acceptance percentage in 2007 was 10.4%

Scholarships

TheGoverning Body

A governing body is a group of people that has the authority to exercise governance over an organization or political entity. The most formal is a government, a body whose sole responsibility and authority is to make binding decisions in a taken g ...

provides financial benefits with school fees to families unable to afford them. Parents of pupils who are given a Scholarship are capable of obtaining a 10% fee deduction, although more than one scholarship can be awarded to one student.

Fees

*Boarder fees per term: 12,266 (GBP) *Day pupil fees per term: 7,696 (GBP)Alumni

There have been a number of notable Old Rugbeians including the purported father of the sport of Rugby William Webb Ellis, the inventor of Australian rules football Tom Wills, the war poets Rupert Brooke and John Gillespie Magee, Jr., Prime Minister

There have been a number of notable Old Rugbeians including the purported father of the sport of Rugby William Webb Ellis, the inventor of Australian rules football Tom Wills, the war poets Rupert Brooke and John Gillespie Magee, Jr., Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasem ...

, author and mathematician Lewis Carroll, poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, the author and social critic Salman Rushdie (who said of his time there: "Almost the only thing I am proud of about going to Rugby school was that Lewis Carroll went there too.") and the Irish writer and republican Francis Stuart. The Indian concert pianist, music composer and singer Adnan Sami also studied at Rugby School. Matthew Arnold's father Thomas Arnold, was a headmaster of the school. Philip Henry Bahr (later Sir Philip Henry Manson-Bahr), a zoologist and medical doctor, World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

veteran, was President of both Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and Medical Society of London, and vice-president of the British Ornithologists' Union. Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly

Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly (1896–1971), MBE, MC, RI, known to friends and colleagues as 'TK', was a British army officer, school teacher, and artist, known especially for his watercolour paintings of ornithological subjects.

Early life ...

joined the army in 1915, straight after leaving the school, earned a Military Cross during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, and later returned to the school as Director of Art.

Rugbeian Society

The Rugbeian Society is for former pupils at the School. An Old Rugbeian is sometimes referred to as an OR. The purposes of the society are to encourage and help Rugbeians in interacting with each other and to strengthen the ties between ORs and the school. In 2010 the Rugbeians reached the semi-finals of the Public Schools' Old Boys' Sevens tournament, hosted by the Old Silhillians to celebrate the 450th anniversary of fellow Warwickshire public school,Solihull School

Solihull School is a coeducational independent day school in Solihull, West Midlands, England. Founded in 1560, it is the oldest school in the town and is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference.

History

In 1560 the reve ...

.

Buildings and architecture

The buildings of Rugby School date from the 18th and 19th century with some early 20th Century additions. The oldest buildings are the Old Quad Buildings and the School House the oldest parts of which date from 1748, but were mostly built between 1809 and 1813 byHenry Hakewill

Henry Hakewill (4 October 1771 – 13 March 1830) was an English architect.

Biography Early life

Henry Hakewell was a pupil of John Yenn, RA, and also studied at the Royal Academy, where in 1790 he was awarded a silver medal for a drawing of ...

, these are Grade II* listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

. Most of the current landmark buildings date from the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edward ...

and were designed by William Butterfield: The most notable of these is the chapel, dating from 1872, which is Grade I listed. Butterfield's New Quad buildings are Grade II* listed and date from 1867 to 1885. The Grade II* War Memorial chapel, designed by Sir Charles Nicholson

Sir Charles Nicholson, 1st Baronet (23 November 1808 – 8 November 1903) was an English-Australian politician, university founder, explorer, pastoralist, antiquarian and philanthropist. The Nicholson Museum at the University of Sydney was na ...

, dates to 1922. Nicholson was educated at the school from the late-1870s.

Head Masters

Thomas Arnold

Rugby's most famous headmaster was Thomas Arnold, appointed in 1828; he executed many reforms to the school curriculum and administration. Arnold's and the school's reputations were immortalised through Thomas Hughes' book '' Tom Brown's School Days.'' David Newsome writes about the new educational methods employed by Arnold in his book, 'Godliness and Good Learning' (Cassell 1961). He calls the morality practised at Arnold's schoolmuscular Christianity

Muscular Christianity is a philosophical movement that originated in England in the mid-19th century, characterized by a belief in patriotic duty, discipline, self-sacrifice, masculinity, and the moral and physical beauty of athleticism.

The mov ...

. Arnold had three principles: religious and moral principle, gentlemanly conduct and academic performance. George Mosse, former professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, lectured on Arnold's time at Rugby. According to Mosse, Thomas Arnold created an institution which fused religious and moral principles, gentlemanly conduct, and learning based on self-discipline. These morals were socially enforced through the "Gospel of work." The object of education was to produce "the Christian gentleman," a man with good outward appearance, playful but earnest, industrious, manly, honest, virginal pure, innocent, and responsible.

John Percival

In 1888 the appointment of Marie Bethell Beauclerc by Percival was the first appointment of a female teacher in an English boys' public school and the first time shorthand had been taught in any such school. The shorthand course was popular with one hundred boys in the classes.Controversy

In September 2005, the school was one of fifty independent schools operating independent school fee-fixing, in breach of theCompetition Act, 1998

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

. All of the schools involved were ordered to abandon this practice, pay a nominal penalty of £10,000 each and to make ex-gratia payments totalling three million pounds into a trust designed to benefit pupils who attended the schools during the period in respect of which fee information had been shared.

However, the head of the Independent Schools Council declared that independent schools had always been exempt from anti-cartel rules applied to business, were following a long-established procedure in sharing the information with each other and that they were unaware of the change to the law (on which they had not been consulted). She wrote to John Vickers, the OFT director-general, stating "They are not a group of businessmen meeting behind closed doors to fix the price of their products to the disadvantage of the consumer. They are schools that have quite openly continued to follow a long-established practice because they were unaware that the law had changed."

See also

* List of schools in the West Midlands * Four Rugby BoysReferences

Further reading

* Carter, George David. "The extent to which the novel" Tom Brown's Schooldays",(1857), by Thomas Hughes, accurately reflects the ideas, purposes and policies of Dr. Thomas Arnold in Rugby School, 1828–1842." (MA thesis, Kansas State U, 1967).online

* Hope-Simpson, John Barclay. ''Rugby Since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842.'' (1967). * Mack, Edward Clarence. ''Public schools and British opinion, 1780 to 1860: An examination of the relationship between contemporary ideas and the evolution of an English institution'' (1938), comparison with other elite schools * Neddam*, Fabrice. "Constructing masculinities under Thomas Arnold of Rugby (1828–1842): gender, educational policy and school life in an early‐Victorian public school." ''Gender and Education'' 16.3 (2004): 303–326. * Rouse, W.H.D. ''A history of Rugby School'' (1898

online

External links

* {{Authority control Boarding schools in Warwickshire Member schools of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference Racquets venues Independent schools in Warwickshire Educational institutions established in the 1560s 1567 establishments in England Schools in Rugby, Warwickshire World Rugby Hall of Fame inductees Cricket grounds in Warwickshire William Butterfield buildings Elinor Lyon