Rufus King on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rufus King (March 24, 1755April 29, 1827) was an American

King played a major diplomatic role as minister to the

King played a major diplomatic role as minister to the

Though King had been a slaveholder as a young man, he became a prominent opponent of slavery.

King had a long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade. That stand was a product of moral conviction, which coincided with the political realities of New England Federalists. While in Congress, he successfully added provisions to the 1787

Though King had been a slaveholder as a young man, he became a prominent opponent of slavery.

King had a long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade. That stand was a product of moral conviction, which coincided with the political realities of New England Federalists. While in Congress, he successfully added provisions to the 1787

At the time of his death in 1827, King had a library of roughly 2,200 titles in 3,500 volumes. In addition, King had roughly 200 bound volumes containing thousands of pamphlets. King's son John Alsop King inherited the library and kept it in

At the time of his death in 1827, King had a library of roughly 2,200 titles in 3,500 volumes. In addition, King had roughly 200 bound volumes containing thousands of pamphlets. King's son John Alsop King inherited the library and kept it in

Many of King's family were also involved in politics, and he had numerous prominent descendants. His brother William King was the first governor of Maine and a prominent merchant, and his other brother,

Many of King's family were also involved in politics, and he had numerous prominent descendants. His brother William King was the first governor of Maine and a prominent merchant, and his other brother,

Halsey Minor

Read the Hook November 27, 2008 is a technology entrepreneur who founded

The King Family Papers at the New York Historical Society

The Rufus King Papers at the New York Historical Society

King Manor Museum

Historic House Trust of New York, King Manor Museum

A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825

The members of the 1st United States Congress

(took seat on July 25, 1789)

The members of the 4th United States Congress

(resigned on May 23, 1796) * {{DEFAULTSORT:King, Rufus 1755 births 1827 deaths People from Scarborough, Maine Gracie-King family American people of English descent American Episcopalians Continental Congressmen from Massachusetts Signers of the United States Constitution Pro-Administration Party United States senators from New York (state) Federalist Party United States senators from New York (state) Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations New York (state) Federalists New York (state) National Republicans 1804 United States vice-presidential candidates 1808 United States vice-presidential candidates Candidates in the 1812 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1816 United States presidential election Members of the New York State Assembly 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to Great Britain Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom 18th-century American diplomats 19th-century American diplomats Members of the Massachusetts General Court Activists from New York City American abolitionists People from Jamaica, Queens Politicians from Newburyport, Massachusetts Politicians from New York City Massachusetts lawyers Lawyers from New York City American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Harvard University alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Antiquarian Society Massachusetts militiamen in the American Revolution Christian abolitionists The Governor's Academy alumni Alsop family

Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. He was a delegate for Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

and the Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

and was one of the signers of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

in 1787. After formation of the new Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

, he represented New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. He emerged as a leading member of the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

and served as the party's last presidential nominee during the 1816 presidential election.

The son of a prosperous Massachusetts merchant, King studied law before he volunteered for the militia during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. He won election to the Massachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, ...

in 1783 and to the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

the following year. At the 1787 Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

, he emerged as a leading nationalist and called for increased powers for the federal government. After the convention, King returned to Massachusetts, where he used his influence to help ratify the Constitution. At the urging of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, he then abandoned his law practice and moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

He won election to represent New York in the United States Senate in 1789 and remained in office until 1796. That year, he accepted President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

's appointment to the position of Minister to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. Though King aligned with Hamilton's Federalist Party, the Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

retained King's services after Jefferson's victory in the 1800 presidential election. King served as the Federalist vice-presidential candidate in the 1804

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Haiti gains independence from France, and becomes the first black republic, having the only successful slave revolt ever.

* February 4 – The Sokoto Caliphate is founded in West Africa.

* Februa ...

and 1808 elections and ran on an unsuccessful ticket with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (February 25, 1746 – August 16, 1825) was an American Founding Father, statesman of South Carolina, Revolutionary War veteran, and delegate to the Constitutional Convention where he signed the United States Constit ...

of South Carolina. Though most Federalists supported the Democratic-Republican DeWitt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and naturalist. He served as a United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the seventh governor of New York. In this last capacity, he was largely res ...

in the 1812 presidential election, King, without the support of his party, won the few votes of the Federalists who were unwilling to support Clinton's candidacy. In 1813, King returned to the Senate and remained in office until 1825.

King, the ''de facto'' Federalist nominee for president in 1816, lost in a landslide to James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. The Federalist Party became defunct at the national level after 1816, and King was the last presidential nominee whom the party fielded. Nonetheless, King was able to remain in the Senate until 1825, which made him the last Federalist senator because of a split in the New York Democratic-Republican Party. King then accepted President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

's appointment to serve another term as ambassador to Great Britain, but ill health forced King to retire from public life, and he died in 1827. King had five children who lived to adulthood, and he has had numerous notable descendants.

Early life

King was born on March 24, 1755, inScarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, which was then part of Massachusetts but is now in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. He was a son of Isabella (Bragdon) and Richard King, a prosperous farmer-merchant, "lumberman, and sea captain" who had settled at Dunstan Landing in Scarborough, near Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropol ...

, and had made a modest fortune by 1755, the year that Rufus was born. His financial success aroused the jealousy of his neighbors, and when the Stamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials i ...

was imposed, and rioting became almost respectable, a mob ransacked his house and destroyed most of the furniture. Nobody was punished, and the next year, the mob burned down his barn. That statement proves true as John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

once referred to that moment in discussing limitations of the "mob" for the Constitutional Convention and wrote a letter to his wife, Abigail

Abigail () was an Israelite woman in the Hebrew Bible married to Nabal; she married the future King David after Nabal's death ( 1 Samuel ). Abigail was David's second wife, after Saul and Ahinoam's daughter, Michal, whom Saul later marri ...

, in which he described the scene:

I am engaged in a famous Cause: The Cause of King, of Scarborough vs. a Mob, that broke into his House, and rifled his Papers, and terrifyed him, his Wife, Children and Servants in the Night. The Terror, and Distress, the Distraction and Horror of this Family cannot be described by Words or painted upon Canvass. It is enough to move a Statue, to melt an Heart of Stone, to read the Story.... It was not surprising that Richard King became aLoyalist Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro .... All of his sons, however, became Patriots during the American War of Independence.

Education and early career

King attended Dummer Academy (nowThe Governor's Academy

The Governor's Academy is an independent school north of Boston located on in the village of Byfield, Massachusetts, United States (town of Newbury), north of Boston. The Academy enrolls approximately 412 students in grades nine through twelve ...

) at the age of twelve in South Byfield, Massachusetts. Later, he attended Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, where he graduated in 1777. Siry, Steven E. (February 2000), "King, Rufus"; '' American National Biography Online''. He began to read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

under Theophilus Parsons

Theophilus Parsons (February 24, 1750October 30, 1813) was an American jurist.

Life

Born in Newbury, Massachusetts to a clergyman father, Parsons was one of the early students at the Dummer Academy (now The Governor's Academy) before matricu ...

, but his studies were interrupted in 1778, when King volunteered for militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

duty during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Appointed a major, he served as an aide to General John Sullivan during the Battle of Rhode Island

The Battle of Rhode Island (also known as the Battle of Quaker Hill) took place on August 29, 1778. Continental Army and Militia forces under the command of Major General John Sullivan had been besieging the British forces in Newport, Rhode Isl ...

. After the campaign, King returned to his apprenticeship under Parsons. He was admitted to the bar in 1780 and began a legal practice in Newburyport, Massachusetts

Newburyport is a coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, northeast of Boston. The population was 18,289 at the 2020 census. A historic seaport with vibrant tourism industry, Newburyport includes part of Plum Island. The mo ...

.

Political career

Constitutional Convention

King was first elected to theMassachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, ...

in 1783 and returned there each year until 1785. Massachusetts sent him to the Confederation Congress

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Marc ...

from 1784 to 1787. He was one of the youngest men at the conference.

In 1787, King was sent to the Constitutional Convention, which was held at Philadelphia. King held a significant position at the convention despite his youthful stature since "he numbered among the most capable orators." Along with James Madison, "he became a leading figure in the nationalist causus." Furthermore, he attended every session. King's major involvements included serving on the Committee on Postponed Matters and the Committee of Style and Arrangement.

Although when he came to the convention, he was still unconvinced that major changes should be made in the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, his views underwent a startling transformation over the debates. He worked with Chairman William Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father and statesman. Before the Revolutionary War, he served as a militia lieutenant before being relieved following his rejection of his election to the Fir ...

, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the U ...

, and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

on the Committee of Style and Arrangement to prepare a final draft of the U.S. Constitution. King was one of the most prominent delegates namely because of playing "a major role in the laborious crafting of the fundamental governing character." The Constitution was signed on September 17 but needed to be ratified by the states. After signing the Constitution, he returned home and went to work to get the Constitution ratified and unsuccessfully positioned himself to be named to the U.S. Senate. The ratification passed by the narrow margin of 187–168. With the ratification passed, Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify the constitution in early February 1788.

King was indirectly responsible for the passing of this ratification because his "learned, informative, and persuasive speeches" convinced a "popular, vain merchant and prince-turned-politicians to abandon his anti-federalism and approve the new organic law."

Later career

After his early political experiences during the Constitutional Convention, King decided to switch his vocational calling by " bandoninghis law practicen 1788

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

ndmoved from the Bay State to Gotham, and entered the New York political forum." At Hamilton's urging, King moved to New York City and was elected to the New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Assem ...

in 1789. Shortly afterwards, he was elected as Senator from New York and was re-elected in 1795. King declined an appointment as Secretary of State to succeed Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

. In 1795, King helped Hamilton defend the controversial Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

by writing pieces for New York newspapers under the pseudonym "Camillus." Of the 38 installments in the series, King wrote eight numbers 23–30, 34, and 35, in which he discussed the treaty's maritime and commercial aspects. He was re-elected in 1795 but resigned on May 23, 1796 after he had been appointed U.S Minister by George Washington to Great Britain. even though King was an outspoken Federalist politically, President Thomas Jefferson, upon his elevation to the presidency, refused to recall him. In 1803, King voluntarily relinquished his position.

King then returned to elected politics, for a long time with little success, but he later returned to the Senate. In April 1804, King ran unsuccessfully for the Senate from New York. Later that year and again in 1808, King and another signer of the Constitution, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, were the candidates for Vice-President and President of the declining Federalist Party, respectively, but they had no realistic chance against the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson since they received only 27.2% of the popular vote and lost by 45.6%. That marked the highest recess in presidential election history. In 1808, both candidates were nominated and lost against James Madison, gaining 32.4% of the popular vote.

In September 1812, the unpopular War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

against Great Britain helped the opposing Federalists to regain their reputation, King led an effort at the Federalist Party caucus to nominate a ticket for the presidential election that year, but the effort failed, as the Democratic-Republican DeWitt Clinton had the best chances to defeat his fellow party member Madison, which made the Federalists field no candidate. However, some sought to make King the nominee to have a candidate under the Federalist banner on the ballot, and though little came of it, he finished third in the popular vote, with approximately 2% of the total. Shortly thereafter, King celebrated his first success after ten years by being elected to his "second tenure on Senate" in 1813.

In April 1816, he ran for governor of New York but lost to Daniel D. Tompkins

Daniel D. Tompkins (June 21, 1774 – June 11, 1825) was an American politician. He was the fifth governor of New York from 1807 to 1817, and the sixth vice president of the United States from 1817 to 1825.

Born in Scarsdale, New York, Tompkins ...

. In the fall of that year, he became the informal presidential nominee for the Federalist Party, as it did not meet for any convention. He received only 30.9% of the popular vote and lost again, this time to James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, whose running mate, coincidentally, was Tompkins. King was the last presidential candidate by the Federalists before their collapse.

When he ran for re-election to the Senate in 1819, he ran as a Federalist even though the party was already disbanding and had only a small minority in the New York State Legislature. However, because of the split of the Democratic-Republicans, no successor was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1819, and the seat remained vacant until January 1820. Trying to attract the former Federalist voters to their side at the next gubernatorial election in April 1820, both factions of the Democratic-Republican Party supported King, who served another term in the U.S. Senate until March 3, 1825. The Federalist Party had already ceased to exist on the federal stage. During King's second tenure in the Senate, he continued his career as an opponent of slavery, which he denounced as anathema to the principles underlying the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

and the Constitution. In what is considered the greatest speech of his career, he spoke against admitting Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

as a slave state in 1820.

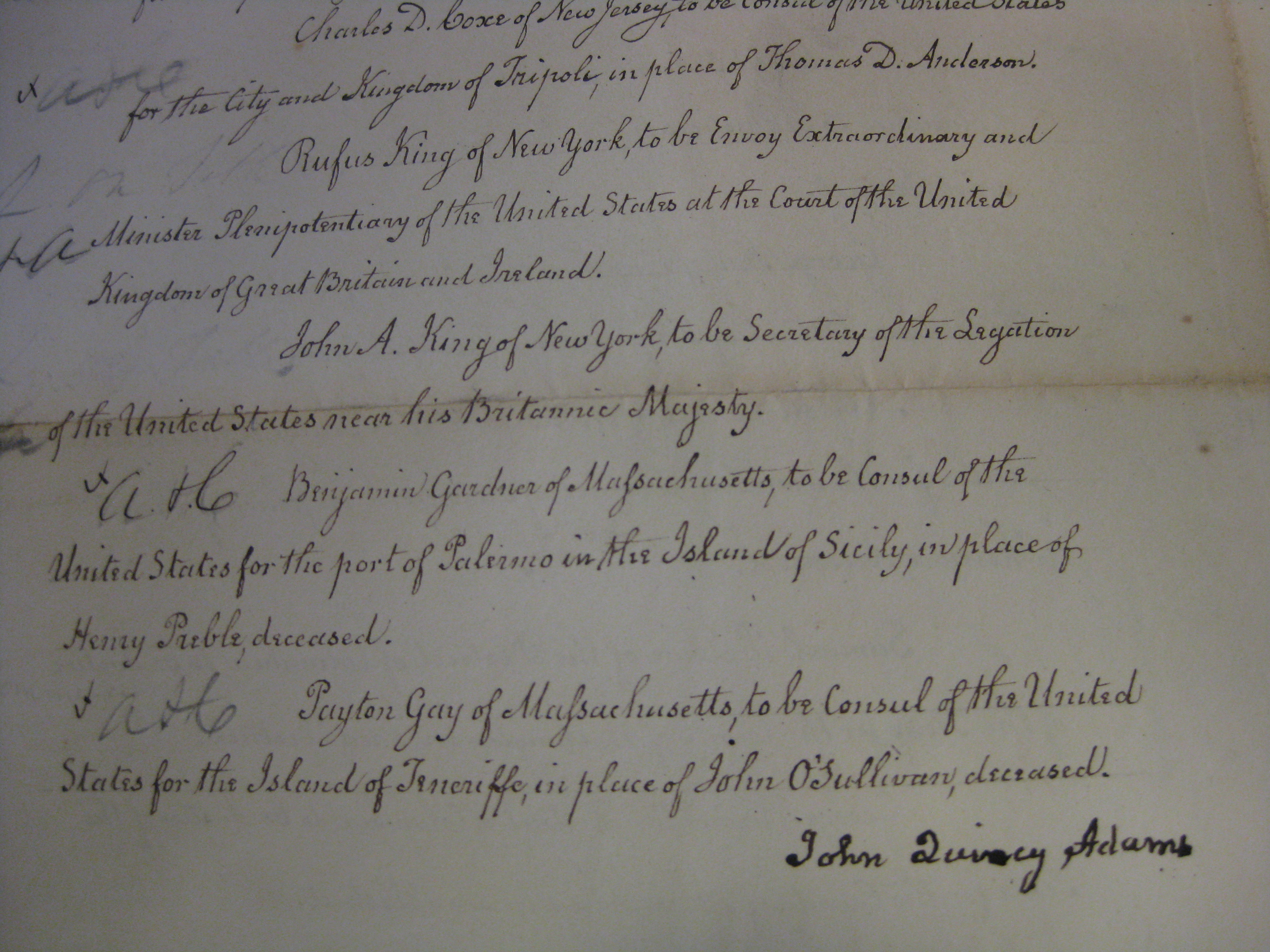

Soon after his second term in the Senate ended, King was appointed minister to Great Britain again, this time by U.S. President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

. However, he was forced to return home a few months later because of his failing health. He then retired from public life.

Diplomat

Court of St James's

The Court of St James's is the royal court for the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. All ambassadors to the United Kingdom are formally received by the court. All ambassadors from the United Kingdom are formally accredited from the court – & ...

from 1796 to 1803 and again from 1825 to 1826. Although he was a leading Federalist, Thomas Jefferson kept him in office until King asked to be relieved. Some prominent accomplishments that King had from his time as a national diplomat include a term of friendly relations with Great Britain and the United States, at least until it became hostile in 1805. With that in mind, he successfully reached a compromise on the passing of the Jay Treaty and was an avid supporter of it.

King was outspoken against potential Irish immigration to the United States in the wake of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1798; Ulster-Scots: ''The Hurries'') was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group influence ...

. In a September 13, 1798 letter to the Duke of Portland

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

, King said of potential Irish refugees, "I certainly do not think they will be a desirable acquisition to any Nation, but in none would they be likely to prove more mischievous than in mine, where from the sameness of language and similarity of Laws and Institutions they have greater opportunities of propagating their principles than in any other Country." Also, while in Britain, King was in close personal contact with the South American revolutionary Francisco de Miranda

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (28 March 1750 – 14 July 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spani ...

and facilitated Miranda's trip to the United States in search of support for his failed 1806 expedition to Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

.

Anti-slavery activity

Though King had been a slaveholder as a young man, he became a prominent opponent of slavery.

King had a long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade. That stand was a product of moral conviction, which coincided with the political realities of New England Federalists. While in Congress, he successfully added provisions to the 1787

Though King had been a slaveholder as a young man, he became a prominent opponent of slavery.

King had a long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade. That stand was a product of moral conviction, which coincided with the political realities of New England Federalists. While in Congress, he successfully added provisions to the 1787 Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

that barred the extension of slavery into the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. However, he also said he was willing "to suffer the continuance of slaves until they can be gradually emancipated in states already overrun with them." He referred to slavery as a "nefarious institution." In 1817, he supported Senate action to abolish the domestic slave trade, and in 1819, he spoke strongly for the anti-slavery amendment to the Missouri statehood bill. In 1819, his arguments were political, economic, and humanitarian. The extension of slavery would adversely affect the security of the principles of freedom and liberty. After the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

, he continued to support gradual emancipation in various ways. In 1821, he fought against attempts to include a discriminatory clause in New York's Constitution that aimed to restrict suffrage on racial grounds, arguing that such a restriction was unconstitutional.

Library

At the time of his death in 1827, King had a library of roughly 2,200 titles in 3,500 volumes. In addition, King had roughly 200 bound volumes containing thousands of pamphlets. King's son John Alsop King inherited the library and kept it in

At the time of his death in 1827, King had a library of roughly 2,200 titles in 3,500 volumes. In addition, King had roughly 200 bound volumes containing thousands of pamphlets. King's son John Alsop King inherited the library and kept it in Jamaica, Queens

Jamaica is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens. It is mainly composed of a large commercial and retail area, though part of the neighborhood is also residential. Jamaica is bordered by Hollis to the east; St. Albans, Springfi ...

, until his death in 1867. The books then went to John's son, Dr. Charles Ray King, of Bucks County, Pennsylvania

Bucks County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 646,538, making it the fourth-most populous county in Pennsylvania. Its county seat is Doylestown. The county is named after the Englis ...

. They remained in Pennsylvania until they were donated to the New-York Historical Society

The New-York Historical Society is an American history museum and library in New York City, along Central Park West between 76th and 77th Streets, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The society was founded in 1804 as New York's first museum. ...

in 1906, where most of them currently reside. Some books have extensive marginalia. In addition, six commonplace books survive in his papers at the New York Historical Society.

Other accomplishments

In his lifetime, King was an avid supporter ofAlexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and his fiscal programs and became a director of the Hamilton-sponsored First Bank of the United States

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

. Among other prominent things that occurred in his life, King was first elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1805 and was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

in 1814. Contrary to his previous position on the national bank of the United States, King found himself denying the reopening of a Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

in 1816. In 1822, he was admitted as an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

.

Family

Cyrus King

Cyrus King (September 6, 1772 – April 25, 1817) was a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, half-brother of Rufus King.

Early life and education

Born in Scarborough in Massachusetts Bay's Province of Maine, King attended Phillips Aca ...

, was a U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

from Massachusetts.

His wife, Mary Alsop, was born in New York on October 17, 1769 and died in Jamaica, New York, on June 5, 1819. She was the only daughter of John Alsop

John Alsop Jr. (1724 – November 22, 1794) was an American merchant and politician from New York City. As a delegate for New York to the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776, he signed the 1774 Continental Association.

Early life

Alsop wa ...

, a wealthy merchant and a delegate for New York to the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776. She was a great-niece of Governor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

. She married King in New York City on March 30, 1786.

Mary King was a lady of remarkable beauty, gentle and gracious manners, and well cultivated mind, and adorned the high station, both in England and at home, that her husband's official positions and their own social relations entitled them to occupy. A King family member once wrote to their wife of her beauty and personality: "Tell Betsy King ufus's half-sisterher sister is a beauty. She is vastly the best looking woman I have seen since I have been in this city.... She is a good hearted woman, and, I think, possesses all that Benevolence and kind, friendly disposition, that never fail to find respectable admirers." Her "remarkable beauty" and "well cultivated manner" seemed to help the Kings in the type of lifestyle in which they lived, one in which the Kings found themselves in "fashionable circles and entertained frequently... (potentially helped by how "rs. King

Rupee is the common name for the currencies of

India, Mauritius, Nepal, Pakistan, Seychelles, and Sri Lanka, and of former currencies of Afghanistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, the United Arab Emirates (as the Gulf rupee), British East Africa, ...

was widely admired in New York society; her retiring nature set her apart."). The Kings had seven children, of which five managed to live to adulthood. On June 5, 1819, Mrs. King died. "She was buried in the old churchyard of Grace Church." Rufus King remarked on her death regarding his wife, "The example of her life is worthy of the imitation of us all."

Rufus King died on April 29, 1827, and his funeral was held at his New York home in Jamaica, Queens

Jamaica is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens. It is mainly composed of a large commercial and retail area, though part of the neighborhood is also residential. Jamaica is bordered by Hollis to the east; St. Albans, Springfi ...

. He is buried in the Grace Church Cemetery, in Jamaica, Queens. The home that King purchased in 1805 and expanded thereafter and some of his farm make up King Park in Queens. The home, called King Manor

King Manor, also known as the Rufus King House, is a historic house at 150th Street and Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica, Queens, New York City. It was the home of Founding Father Rufus King, a signatory of the United States Constitution, New York ...

, is now a museum open to the public. The Rufus King School, also known as P.S. 26, in Fresh Meadows, New York

Fresh Meadows is a neighborhood in the northeastern section of the New York City borough of Queens. Fresh Meadows used to be part of the broader town of Flushing and is bordered to the north by the Horace Harding Expressway; to the west by Pom ...

, was named after King, as was the Rufus King Hall on the City University of New York Queens College

Queens College (QC) is a public college in the Queens borough of New York City. It is part of the City University of New York system. Its 80-acre campus is primarily located in Flushing, Queens. It has a student body representing more than 170 ...

campus and King Street in Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the county seat of Dane County and the capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census the population was 269,840, making it the second-largest city in Wisconsin by population, after Milwaukee, and the 80th-lar ...

.

Descendants and relatives

Rufus King's descendants and relatives number in the thousands today. Some of his notable descendants include the following: * Dr.C. Loring Brace

Charles Loring Brace IV (December 19, 1930 – September 7, 2019) was an American anthropologist, Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan's Department of Anthropology and Curator Emeritus at the University's Museum of Anthropological Arc ...

IV was a noted biological anthropologist.

* Gerald Warner Brace (1901–1978) was an American writer, educator, sailor, and boat builder.

* Charles Loring Brace

Charles Loring Brace (June 19, 1826 – August 11, 1890) was an American philanthropist who contributed to the field of social reform. He is considered a father of the modern foster care movement and was most renowned for starting the Orphan T ...

(1826–1890) was a philanthropist and was most renowned for founding the Children's Aid Society

Children's Aid, formerly the Children's Aid Society, is a private child welfare nonprofit in New York City founded in 1853 by Charles Loring Brace. With an annual budget of over $100 million, 45 citywide sites, and over 1,200 full-time employees ...

.

* Wolcott Gibbs

Wolcott Gibbs (March 15, 1902 – August 16, 1958) was an American editor, humorist, theatre critic, playwright and writer of short stories, who worked for ''The New Yorker'' magazine from 1927 until his death. He is notable for his 1936 parody o ...

was an American editor, humorist, theater critic, playwright, and author of short stories.

* Archibald Gracie III

Archibald Gracie III (December 1, 1832 – December 2, 1864) was a career United States Army officer, businessman, and a graduate of West Point. He is well known for being a Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War and for his ...

was a career United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

officer, businessman, and a graduate of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

. He is well known for being a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and for his death during the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

.

* Archibald Gracie IV

Archibald Gracie IV (January 15, 1858 – December 4, 1912) was an American writer, soldier, amateur historian, real estate investor, and survivor of the sinking of RMS ''Titanic''. Gracie survived the sinking by climbing aboard an overturned ...

was an American writer, amateur historian, real estate investor, and survivor of the sinking of the RMS ''Titanic''.

* Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey Jr., United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

* Isabella Beecher Hooker

Isabella Beecher Hooker (February 22, 1822 – January 25, 1907) was a leader, lecturer and social activist in the American suffragist movement.

Early life

Isabella Holmes Beecher was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the fifth child and secon ...

(1822–1907) was a leader in the women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement and an author.

* Charles King (academic) was an American academic, politician, and newspaper editor and the ninth president of Columbia College (now Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

).

* Charles King was a United States soldier and a distinguished writer.

* James G. King was an American businessman and Whig Party politician who represented New Jersey's 5th congressional district

New Jersey's 5th congressional district is represented by Democrat Josh Gottheimer, who has served in Congress since 2017. The district stretches across the entire northern border of the state and contains most of Bergen County, as well as p ...

in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. His daughter, Frederika Gore King, married Bancroft Davis

John Chandler Bancroft Davis (December 29, 1822 – December 27, 1907), commonly known as (J. C.) Bancroft Davis, was an attorney, diplomat, judge of the Court of Claims and Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Edu ...

.

* John Alsop King

John Alsop King (January 3, 1788July 7, 1867) was an American politician who was Governor of New York from 1857 to 1858.

Life

John Alsop King was born in the area now encompassed by New York City on January 3, 1788, to U.S. Senator Rufus King ...

was an American politician who served as governor (1857–1859) of New York.

* Rufus King was a newspaper editor, educator, U.S. diplomat, and Union brigadier general during the American Civil War.

* Rufus King Jr. was an artillery officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War and a Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

recipient.

* Rufus Gunn King III was the chief judge of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia

The Superior Court of the District of Columbia, commonly referred to as DC Superior Court, is the trial court for the District of Columbia, in the United States. It hears cases involving criminal and civil law, as well as family court, landlor ...

.

* Alice Duer Miller

Alice Duer Miller (July 28, 1874 – August 22, 1942) was an American writer whose poetry actively influenced political opinion. Her feminist verses influenced political opinion during the American suffrage movement, and her verse novel ''The W ...

was an American writer and poet.

* Halsey Minor

Halsey McLean Minor Sr. is an American businessman who is known for founding CNET in 1993, the first comprehensive consumer-facing technology content publisher. He is also the founder or co-founder of the technology companies such as the virtual ...

Read the Hook November 27, 2008

CNET

''CNET'' (short for "Computer Network") is an American media website that publishes reviews, news, articles, blogs, podcasts, and videos on technology and consumer electronics globally. ''CNET'' originally produced content for radio and televi ...

in 1993.

* Mary Alsop King Waddington was an American author.

See also

*List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines

United States presidents typically fill their Cabinets and other appointive positions with people from their own political party. The first Cabinet formed by the first president, George Washington, included some of Washington's political opponents ...

References

Bibliography

* * Brush, Edward Hale. ''Rufus King and His Times''. New York: Nicholas L. Brown, 1926. * King, Charles R. ''The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King'', 4 vol. 1893–1897. * Perkins, Bradford. ''The First Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1795–1805''. University of California Press, 1967.External links

The King Family Papers at the New York Historical Society

The Rufus King Papers at the New York Historical Society

King Manor Museum

Historic House Trust of New York, King Manor Museum

A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825

The members of the 1st United States Congress

(took seat on July 25, 1789)

The members of the 4th United States Congress

(resigned on May 23, 1796) * {{DEFAULTSORT:King, Rufus 1755 births 1827 deaths People from Scarborough, Maine Gracie-King family American people of English descent American Episcopalians Continental Congressmen from Massachusetts Signers of the United States Constitution Pro-Administration Party United States senators from New York (state) Federalist Party United States senators from New York (state) Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations New York (state) Federalists New York (state) National Republicans 1804 United States vice-presidential candidates 1808 United States vice-presidential candidates Candidates in the 1812 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1816 United States presidential election Members of the New York State Assembly 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to Great Britain Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom 18th-century American diplomats 19th-century American diplomats Members of the Massachusetts General Court Activists from New York City American abolitionists People from Jamaica, Queens Politicians from Newburyport, Massachusetts Politicians from New York City Massachusetts lawyers Lawyers from New York City American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Harvard University alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Antiquarian Society Massachusetts militiamen in the American Revolution Christian abolitionists The Governor's Academy alumni Alsop family