Ruff (bird) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ruff (''Calidris pugnax'') is a medium-sized

The ruff is a

The ruff is a

The females, or "reeve", is long with a wingspan, and weighs about . In breeding plumage, they have grey-brown upperparts with white-fringed, dark-centred feathers. The breast and flanks are variably blotched with black. In winter, the females' plumage is similar to that of the male, but the sexes are distinguishable by their size. The plumage of the juvenile ruff resembles the non-breeding adult, but has upperparts with a neat, scale-like pattern with dark feather centres, and a strong buff tinge to the underparts.

Adult male ruffs start to

The females, or "reeve", is long with a wingspan, and weighs about . In breeding plumage, they have grey-brown upperparts with white-fringed, dark-centred feathers. The breast and flanks are variably blotched with black. In winter, the females' plumage is similar to that of the male, but the sexes are distinguishable by their size. The plumage of the juvenile ruff resembles the non-breeding adult, but has upperparts with a neat, scale-like pattern with dark feather centres, and a strong buff tinge to the underparts.

Adult male ruffs start to

The ruff is a migratory species, breeding in wetlands in colder regions of northern Eurasia, and spends the northern winter in the

The ruff is a migratory species, breeding in wetlands in colder regions of northern Eurasia, and spends the northern winter in the  It is highly gregarious on migration, travelling in large flocks that can contain hundreds or thousands of individuals. Huge dense groups form on the wintering grounds; one flock in

It is highly gregarious on migration, travelling in large flocks that can contain hundreds or thousands of individuals. Huge dense groups form on the wintering grounds; one flock in

Males display during the breeding season at a

Males display during the breeding season at a  Although satellite males are on average slightly smaller and lighter than residents, the nutrition of the chicks does not, as previously thought, influence mating strategy; rather, the inherited mating strategy influences body size. Resident-type chicks will, if provided with the same amount of food, grow heavier than satellite-type chicks. Satellite males do not have to expend energy to defend a territory, and can spend more time foraging, so they do not need to be as bulky as the residents; indeed, since they fly more, there would be a physiological cost to additional weight.

A third type of male was first described in 2006; this is a permanent female mimic, the first such reported for a bird. About 1% of males are small, intermediate in size between males and females, and do not grow the elaborate breeding plumage of the territorial and satellite males, although they have much larger internal

Although satellite males are on average slightly smaller and lighter than residents, the nutrition of the chicks does not, as previously thought, influence mating strategy; rather, the inherited mating strategy influences body size. Resident-type chicks will, if provided with the same amount of food, grow heavier than satellite-type chicks. Satellite males do not have to expend energy to defend a territory, and can spend more time foraging, so they do not need to be as bulky as the residents; indeed, since they fly more, there would be a physiological cost to additional weight.

A third type of male was first described in 2006; this is a permanent female mimic, the first such reported for a bird. About 1% of males are small, intermediate in size between males and females, and do not grow the elaborate breeding plumage of the territorial and satellite males, although they have much larger internal

The nest is a shallow ground scrape lined with grass leaves and stems, and concealed in marsh plants or tall grass up to from the lek. Nesting is solitary, although several females may lay in the general vicinity of a lek. The eggs are slightly glossy, green or olive, and marked with dark blotches; they are laid from mid-March to early June depending on latitude.

The typical clutch is four eggs, each egg measuring in size and weighing of which 5% is shell. Incubation is by the female alone, and the time to hatching is 20–23 days, with a further 25–28 days to fledging. The

The nest is a shallow ground scrape lined with grass leaves and stems, and concealed in marsh plants or tall grass up to from the lek. Nesting is solitary, although several females may lay in the general vicinity of a lek. The eggs are slightly glossy, green or olive, and marked with dark blotches; they are laid from mid-March to early June depending on latitude.

The typical clutch is four eggs, each egg measuring in size and weighing of which 5% is shell. Incubation is by the female alone, and the time to hatching is 20–23 days, with a further 25–28 days to fledging. The

During the breeding season, the ruff’s diet consists almost exclusively of the adults and larva of terrestrial and aquatic insects such as beetles and flies. On migration and during the winter, the ruff eats insects (including caddis flies, water-beetles,

During the breeding season, the ruff’s diet consists almost exclusively of the adults and larva of terrestrial and aquatic insects such as beetles and flies. On migration and during the winter, the ruff eats insects (including caddis flies, water-beetles,

Ruffs were formerly trapped for food in England in large numbers; on one occasion, 2,400 were served at Archbishop Neville's enthronement banquet in 1465. The birds were netted while lekking, sometimes being fattened with bread, milk and seed in holding pens before preparation for the table.

Ruffs were formerly trapped for food in England in large numbers; on one occasion, 2,400 were served at Archbishop Neville's enthronement banquet in 1465. The birds were netted while lekking, sometimes being fattened with bread, milk and seed in holding pens before preparation for the table.

The most important breeding populations in Europe, in Russia and Sweden are stable, and the breeding range in Norway has expanded to the south, but populations have more than halved in Finland, Estonia, Poland, Latvia and The Netherlands. Although the small populations in these countries are of limited overall significance, the decline is a continuation of trend towards range contraction that has occurred over the last two centuries. The drop in numbers in Europe has been attributed to drainage, increased fertiliser use, the loss of formerly mown or grazed breeding sites and over-hunting.

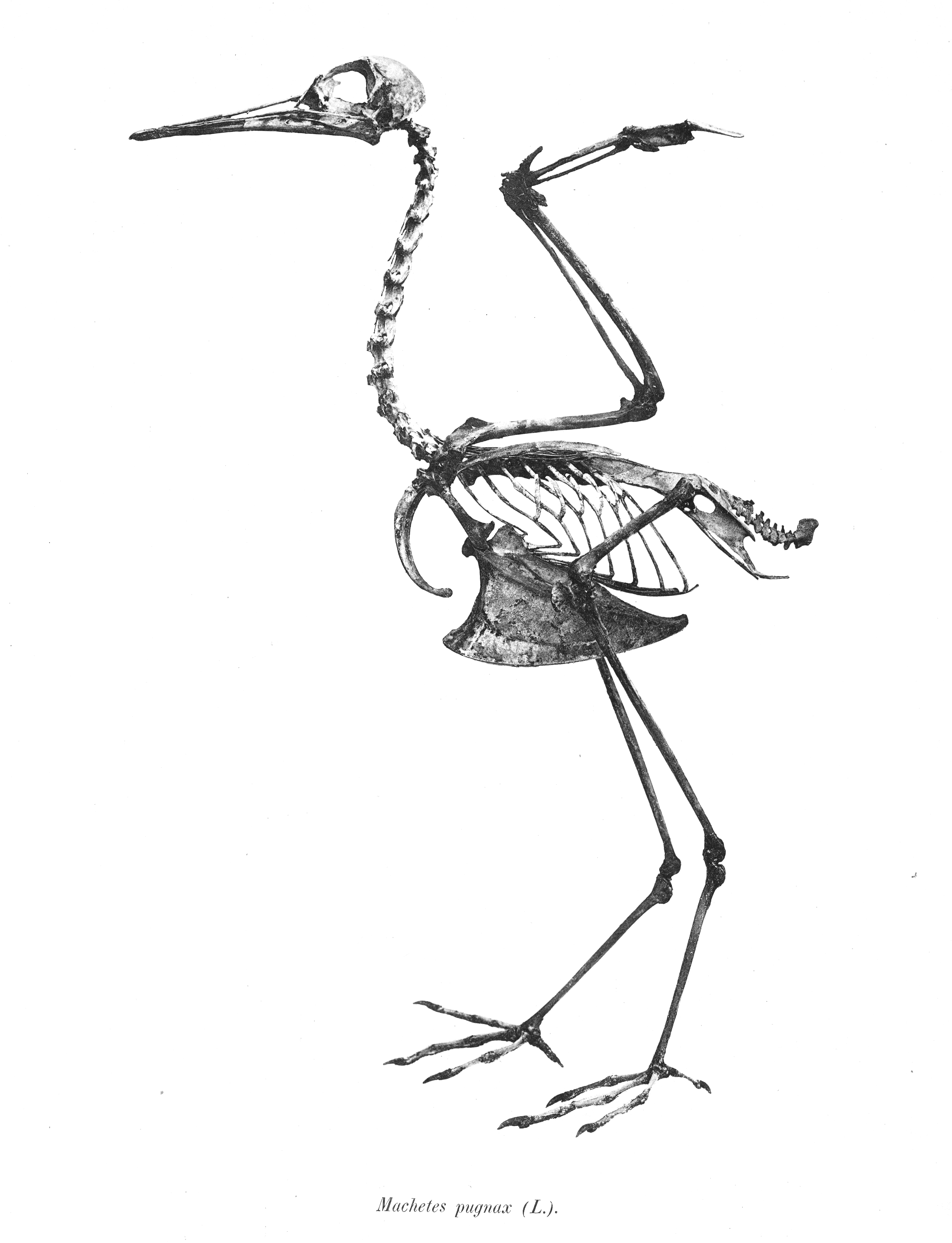

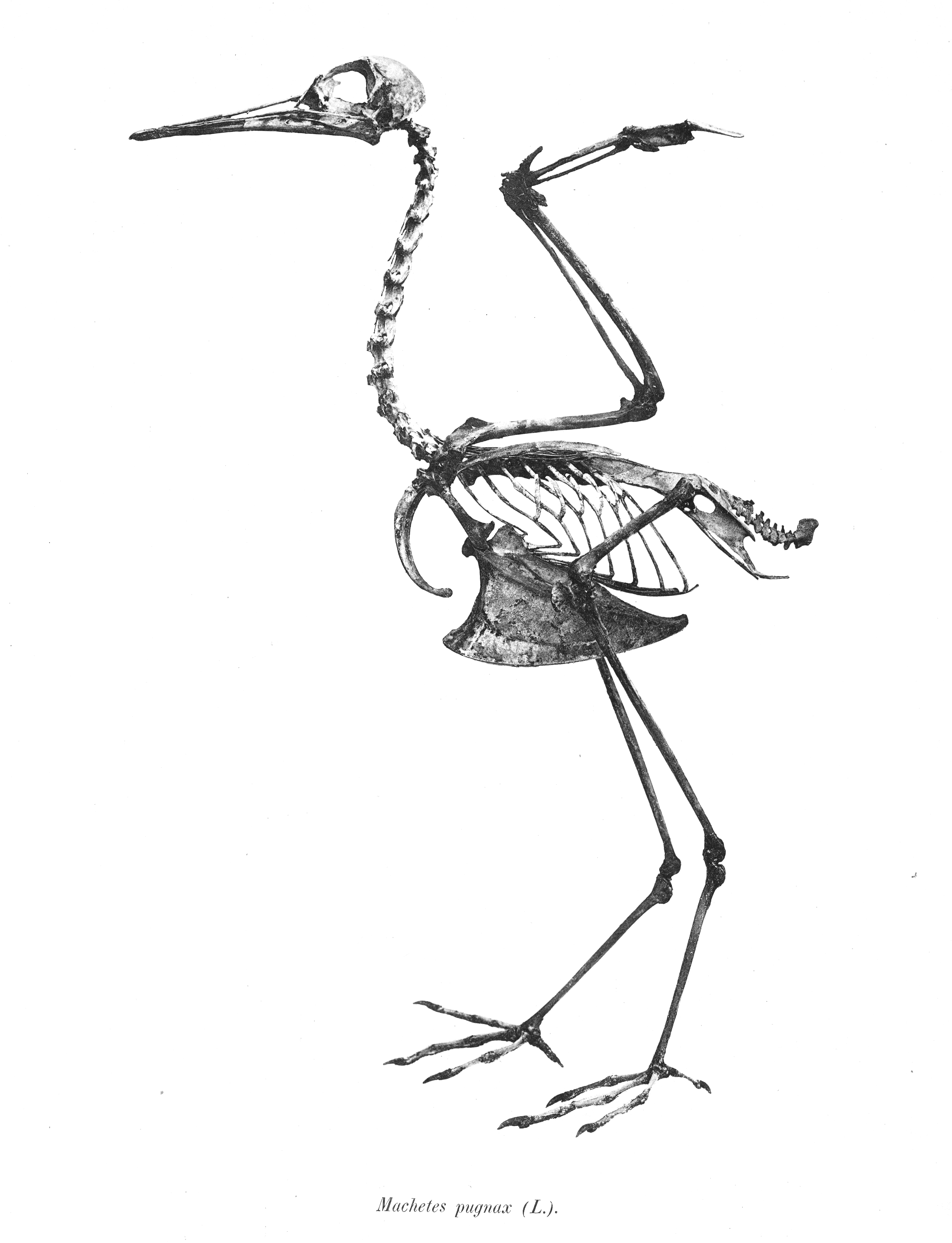

Fossils from the

The most important breeding populations in Europe, in Russia and Sweden are stable, and the breeding range in Norway has expanded to the south, but populations have more than halved in Finland, Estonia, Poland, Latvia and The Netherlands. Although the small populations in these countries are of limited overall significance, the decline is a continuation of trend towards range contraction that has occurred over the last two centuries. The drop in numbers in Europe has been attributed to drainage, increased fertiliser use, the loss of formerly mown or grazed breeding sites and over-hunting.

Fossils from the

The ruff has three male forms, which differ in mating behaviour and in appearance: the typical territorial males which have a dark neck ruff, satellite males which have a white neck ruff, and the very rare cryptic males known as "faeders" which have female-like plumage. The behaviour and appearance of each individual male remain constant through its adult life, and are determined by a simple genetic polymorphism. Territorial behaviour and appearance is

The ruff has three male forms, which differ in mating behaviour and in appearance: the typical territorial males which have a dark neck ruff, satellite males which have a white neck ruff, and the very rare cryptic males known as "faeders" which have female-like plumage. The behaviour and appearance of each individual male remain constant through its adult life, and are determined by a simple genetic polymorphism. Territorial behaviour and appearance is

Ruff species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

* Ruffs on postage stamps

www.birdtheme.org

an

Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.0 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

* * * * * * * {{Authority control Calidris Wading birds Birds of Russia Birds of Scandinavia Birds of Africa Birds described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

wading bird

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

that breeds in marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

es and wet meadow

A meadow ( ) is an open habitat, or field, vegetated by grasses, herbs, and other non-woody plants. Trees or shrubs may sparsely populate meadows, as long as these areas maintain an open character. Meadows may be naturally occurring or artifi ...

s across northern Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

. This highly gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother wasp ...

sandpiper

Sandpipers are a large family, Scolopacidae, of waders. They include many species called sandpipers, as well as those called by names such as curlew and snipe. The majority of these species eat small invertebrates picked out of the mud or soil ...

is migratory and sometimes forms huge flocks in its winter grounds, which include southern and western Europe, Africa, southern Asia and Australia.

The ruff is a long-necked, pot-bellied bird. This species shows marked sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

; the male is much larger than the female (the reeve), and has a breeding plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

that includes brightly coloured head tufts, bare orange facial skin, extensive black on the breast, and the large collar of ornamental feathers that inspired this bird's English name. The female and the non-breeding male have grey-brown upperparts and mainly white underparts. Three differently plumaged types of male, including a rare form that mimics the female, use a variety of strategies to obtain mating opportunities at a lek

Lek or LEK may refer to:

* Lek mating, mating in a lek, a type of animal territory in which males of a species gather

* Albanian lek, the currency of Albania

* Lek (magazine), a Norwegian softcore pornographic magazine

* Lek (pharmaceutical comp ...

, and the colourful head and neck feathers are erected as part of the elaborate main courting display. The female has one brood per year and lays four eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

in a well-hidden ground nest

A nest is a structure built for certain animals to hold eggs or young. Although nests are most closely associated with birds, members of all classes of vertebrates and some invertebrates construct nests. They may be composed of organic materia ...

, incubating the eggs and rearing the chicks, which are mobile soon after hatching, on her own. Predators of wader chicks and eggs include mammals such as fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

es, feral cat

A feral cat or a stray cat is an unowned domestic cat (''Felis catus'') that lives outdoors and avoids human contact: it does not allow itself to be handled or touched, and usually remains hidden from humans. Feral cats may breed over dozens ...

s and stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine, Beringian ermine and ermine, is a mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern portions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Conc ...

s, and birds such as large gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century ...

s, corvids

Corvidae is a cosmopolitan family of oscine passerine birds that contains the crows, ravens, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs, and nutcrackers. In colloquial English, they are known as the crow family or corvids. Currently, 13 ...

and skua

The skuas are a group of predatory seabirds with seven species forming the genus ''Stercorarius'', the only genus in the family Stercorariidae. The three smaller skuas, the long-tailed skua, the Arctic skua, and the pomarine skua are called ...

s.

The ruff forage

Forage is a plant material (mainly plant leaves and stems) eaten by grazing livestock. Historically, the term ''forage'' has meant only plants eaten by the animals directly as pasture, crop residue, or immature cereal crops, but it is also used m ...

s in wet grassland and soft mud, probing or searching by sight for edible items. It primarily feeds on insects, especially in the breeding season, but it will consume plant material, including rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

and maize, on migration and in winter. Classified as "least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

" on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biol ...

criteria, the global conservation

Conservation is the preservation or efficient use of resources, or the conservation of various quantities under physical laws.

Conservation may also refer to:

Environment and natural resources

* Nature conservation, the protection and managem ...

concerns are relatively low because of the large numbers that breed in Scandinavia and the Arctic. However, the range in much of Europe is contracting because of land drainage, increased fertiliser use, the loss of mown or grazed breeding sites, and over-hunting. This decline has seen it listed in the ''Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds

The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, or African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) is an independent international treaty developed under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme's Conventio ...

'' (AEWA).

Taxonomy and nomenclature

The ruff is a

The ruff is a wader

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

in the large family Scolopacidae

Sandpipers are a large family, Scolopacidae, of waders. They include many species called sandpipers, as well as those called by names such as curlew and snipe. The majority of these species eat small invertebrates picked out of the mud or soil. ...

, the typical shorebirds. Recent research suggests that its closest relatives are the broad-billed sandpiper, ''Calidris falcinellus'', and the sharp-tailed sandpiper, ''Calidris acuminata''. It has no recognised subspecies or geographical variants.

This species was first described by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

in his ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nomen ...

'' in 1758 as ''Tringa pugnax''. It was moved to the monotypic genus ''Philomachus'' by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

naturalist Blasius Merrem in 1804. More recent DNA research has shown it fits comfortably into the wader genus ''Calidris''. The genus name comes from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

''kalidris'' or ''skalidris'', a term used by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

for some grey-coloured waterside birds. The specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

refers to the aggressive behaviour of the bird at its mating arenas — ''pugnax'' from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

term for "combative".

The original English name for this bird, dating back to at least 1465, is the ''ree'', perhaps derived from a dialectical term meaning "frenzied"; a later name ''reeve'', which is still used for the female, is of unknown origin, but may be derived from the shire-reeve, a feudal officer, likening the male's flamboyant plumage to the official's robes. The current name was first recorded in 1634, and is derived from the ruff

Ruff may refer to:

Places

*Ruff, Virginia, United States, an unincorporated community

*Ruff, Washington, United States, an unincorporated community

Other uses

*Ruff (bird) (''Calidris pugnax'' or ''Philomachus pugnax''), a bird in the wader fami ...

, an exaggerated collar fashionable from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century, since the male bird's neck ornamental feathers resemble the neck-wear.

Description

The ruff has a distinctive gravy boat appearance, with a small head, medium-length bill, longish neck and pot-bellied body. It has long legs that are variable in colour, being dark greenish in juveniles, pink to orange in adults with some males having reddish orange legs only during the breeding season. In flight, it has a deeper, slower wing stroke than other waders of a similar size, and displays a thin, indistinct white bar on the wing, and white ovals on the sides of the tail. The species showssexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

. Although a small percentage of males resemble females, the typical male is much larger than the female and has an elaborate breeding plumage. The males are long with a wingspan, and weighs about . In the May-to-June breeding season, the male's legs, bill and warty bare facial skin are orange, and they have distinctive head tufts and a neck ruff. These ornaments vary on individual birds, being black, chestnut or white, with the colouring solid, barred or irregular. The grey-brown back has a scale-like pattern, often with black or chestnut feathers, and the underparts are white with extensive black on the breast. The extreme variability of the main breeding plumage is thought to have developed to aid individual recognition in a species that has communal breeding displays, but is usually mute.

Outside the breeding season, the male's head and neck decorations and the bare facial skin are lost and the legs and bill become duller. The upperparts are grey-brown, and the underparts are white with grey mottling on the breast and flanks.

The females, or "reeve", is long with a wingspan, and weighs about . In breeding plumage, they have grey-brown upperparts with white-fringed, dark-centred feathers. The breast and flanks are variably blotched with black. In winter, the females' plumage is similar to that of the male, but the sexes are distinguishable by their size. The plumage of the juvenile ruff resembles the non-breeding adult, but has upperparts with a neat, scale-like pattern with dark feather centres, and a strong buff tinge to the underparts.

Adult male ruffs start to

The females, or "reeve", is long with a wingspan, and weighs about . In breeding plumage, they have grey-brown upperparts with white-fringed, dark-centred feathers. The breast and flanks are variably blotched with black. In winter, the females' plumage is similar to that of the male, but the sexes are distinguishable by their size. The plumage of the juvenile ruff resembles the non-breeding adult, but has upperparts with a neat, scale-like pattern with dark feather centres, and a strong buff tinge to the underparts.

Adult male ruffs start to moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

into the main display plumage before their return to the breeding areas, and the proportion of birds with head and neck decorations gradually increases through the spring. Second-year birds lag behind full adults in developing breeding plumage. They have a lower body mass and a slower weight increase than full adults, and perhaps the demands made on their energy reserves during the migration flight are the main reason of the delayed moult.

Ruffs of both sexes have an additional moult stage between the winter and final summer plumages, a phenomenon also seen in the bar-tailed godwit

The bar-tailed godwit (''Limosa lapponica'') is a large and strongly migratory wader in the family Scolopacidae, which feeds on bristle-worms and shellfish on coastal mudflats and estuaries. It has distinctive red breeding plumage, long legs, an ...

. Before developing the full display finery with coloured ruff and tufts, the males replace part of their winter plumage with striped feathers. Females also develop a mix of winter and striped feathers before reaching their summer appearance. The final male breeding plumage results from the replacement of both winter and striped feathers, but the female retains the striped feathers and replaces only the winter feathers to reach her summer plumage. The striped prenuptial plumages may represent the original breeding appearance of this species, the male's showy nuptial feathers evolving later under strong sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of t ...

pressures.

Adult males and most adult females start their pre-winter moult before returning south, but complete most feather replacement on the wintering grounds. In Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

, males moult 3–4 weeks ahead of the females, finishing before December, whereas females typically complete feather replacement during December and early January. Juveniles moult from their first summer body plumage into winter plumage during late September to November, and later undergo a pre-breeding moult similar in timing and duration to that of the adults, and often producing as brightly coloured an appearance.

Two other waders can be confused with the ruff. The juvenile sharp-tailed sandpiper

The sharp-tailed sandpiper (''Calidris acuminata'') (but see below) is a small wader.

Taxonomy

A review of data has indicated that this bird should perhaps better be placed into the genus ''Philomachus''

– as ''P. acuminatus'' – which now ...

is a little smaller than a juvenile female ruff and has a similar rich orange-buff breast, but the ruff is slimmer with a longer neck and legs, a rounder head, and a much plainer face. The buff-breasted sandpiper

The buff-breasted sandpiper (''Calidris subruficollis'') is a small wader, shorebird. The species name ''subruficollis'' is from Latin ''subrufus'', "reddish" (from ''sub'', "somewhat", and ''rufus'', "rufous") and ''collis'', "-necked/-throated" ...

also resembles a small juvenile ruff, but even the female ruff is noticeably larger than the sandpiper, with a longer bill, more rotund body and scaly-patterned upperparts.

Distribution and habitat

The ruff is a migratory species, breeding in wetlands in colder regions of northern Eurasia, and spends the northern winter in the

The ruff is a migratory species, breeding in wetlands in colder regions of northern Eurasia, and spends the northern winter in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

, mainly in Africa. Some Siberian breeders undertake an annual round trip of up to to the West African wintering grounds. There is a limited overlap of the summer and winter ranges in western Europe. The ruff breeds in extensive lowland freshwater marshes and damp grasslands. It avoids barren tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

and areas badly affected by severe weather, preferring hummocky marshes and deltas with shallow water. The wetter areas provide a source of food, the mounds and slopes may be used for leks

A lek is an aggregation of male animals gathered to engage in competitive displays and courtship rituals, known as lekking, to entice visiting females which are surveying prospective partners with which to mate. A lek can also indicate an avail ...

, and dry areas with sedge

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' wit ...

or low scrub offer nesting sites. A Hungarian study showed that moderately intensive grazing of grassland, with more than one cow per hectare (2.5 acres), was found to attract more nesting pairs. When not breeding, the birds use a wider range of shallow wetlands, such as irrigated fields, lake margins, and mining subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope move ...

and other floodlands. Dry grassland, tidal mudflats and the seashore are less frequently used. The density can reach 129 individuals per square kilometre (334 per square mile), but is usually much lower.

The ruff breeds in Europe and Asia from Scandinavia and Great Britain almost to the Pacific. In Europe it is found in cool temperate areas, but over its Russian range it is an Arctic species, occurring mainly north of about 65°N. The largest numbers breed in Russia (more than 1 million pairs), Sweden (61,000 pairs), Finland (39,000 pairs) and Norway (14,000 pairs). Although it also breeds from Britain east through the Low Countries to Poland, Germany and Denmark, there are fewer than 2,000 pairs in these more southerly areas.

It is highly gregarious on migration, travelling in large flocks that can contain hundreds or thousands of individuals. Huge dense groups form on the wintering grounds; one flock in

It is highly gregarious on migration, travelling in large flocks that can contain hundreds or thousands of individuals. Huge dense groups form on the wintering grounds; one flock in Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

contained a million birds. A minority winter further east to Burma, south China, New Guinea and scattered parts of southern Australia, or on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Europe. In Great Britain and parts of coastal western Europe, where the breeding and wintering ranges overlap, birds may be present throughout the year. Non-breeding birds may also remain year round in the tropical wintering quarters. The Ruff is an uncommon visitor to Alaska (where it has occasionally bred), Canada and the contiguous states of the US, and has wandered to Iceland, Middle America, northern South America, Madagascar and New Zealand. It has been recorded as breeding well south of its main range in northern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, a major migration stopover area.

The male, which plays no part in nesting or chick care, leaves the breeding grounds in late June or early July, followed later in July by the female and juveniles. Males typically make shorter flights and winter further north than females; for example, virtually all wintering ruffs in Britain are males, whereas in Kenya most are females. Many migratory species use this differential wintering strategy, since it reduces feeding competition between the sexes and enables territorial males to reach the breeding grounds as early as possible, improving their chances of successful mating. Male ruffs may also be able to tolerate colder winter conditions because they are larger than females.

Birds returning north in spring across the central Mediterranean appear to follow a well-defined route. Large concentrations of ruffs form every year at particular stopover

250px, Layover for buses at LACMTA's Warner Center Transit Hub, Los Angeles ">Los_Angeles.html" ;"title="Warner Center Transit Hub, Los Angeles">Warner Center Transit Hub, Los Angeles

In scheduled transportation, a layover (also waypoint, way ...

sites to feed, and individuals marked with rings

Ring may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

:(hence) to initiate a telephone connection

Arts, entertainment and media Film and ...

or dye reappear in subsequent years. The refuelling sites are closer together than the theoretical maximum travel distance calculated from the mean body mass, and provide evidence of a migration strategy using favoured intermediate sites. The ruff stores fat as a fuel, but unlike mammals, uses lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

s as the main energy source for exercise (including migration) and, when necessary, keeps warm by shivering; however, little research has been conducted on the mechanisms by which they oxidise

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

lipids.

Behaviour

Mating

Males display during the breeding season at a

Males display during the breeding season at a lek

Lek or LEK may refer to:

* Lek mating, mating in a lek, a type of animal territory in which males of a species gather

* Albanian lek, the currency of Albania

* Lek (magazine), a Norwegian softcore pornographic magazine

* Lek (pharmaceutical comp ...

in a traditional open grassy arena. The ruff is one of the few lekking species in which the display is primarily directed at other males rather than to the females, and it is among the small percentage of birds in which the males have well-marked and inherited variations in plumage and mating behaviour. There are three male forms: the typical territorial males, satellite males which have a white neck ruff, and a very rare variant with female-like plumage. The behaviour and appearance for an individual male remain constant through its adult life, and are determined by its gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s (see §Biology of variation among males).

The territorial males, about 84% of the total, have strongly coloured black or chestnut ruffs and stake out and occupy small mating territories in the lek. They actively court females and display a high degree of aggression towards other resident males; 5–20 territorial males each hold an area of the lek about across, usually with bare soil in the centre. They perform an elaborate display that includes wing fluttering, jumping, standing upright, crouching with ruff erect, or lunging at rivals. They are typically silent even when displaying, although a soft ''gue-gue-gue'' may occasionally be given.

Territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

males are very site-faithful; 90% return to the same lekking sites in subsequent seasons, the most dominant males being the most likely to reappear. Site-faithful males can acquire accurate information about the competitive abilities of other males, leading to well-developed dominance relationships. Such stable relationships reduce conflict and the risk of injury, and the consequent lower levels of male aggression are less likely to scare off females. Lower-ranked territorial males also benefit from site fidelity since they can remain on the leks while waiting for the top males eventually to drop out.

Satellite males, about 16% of the total number, have white or mottled ruffs and do not occupy territories; they enter leks and attempt to mate with the females visiting the territories occupied by the resident males. Resident males tolerate the satellite birds because, although they are competitors for mating with the females, the presence of both types of male on a territory attracts additional females. Females also prefer larger leks, and leks surrounded by taller plants, which give better nesting habitat.

Although satellite males are on average slightly smaller and lighter than residents, the nutrition of the chicks does not, as previously thought, influence mating strategy; rather, the inherited mating strategy influences body size. Resident-type chicks will, if provided with the same amount of food, grow heavier than satellite-type chicks. Satellite males do not have to expend energy to defend a territory, and can spend more time foraging, so they do not need to be as bulky as the residents; indeed, since they fly more, there would be a physiological cost to additional weight.

A third type of male was first described in 2006; this is a permanent female mimic, the first such reported for a bird. About 1% of males are small, intermediate in size between males and females, and do not grow the elaborate breeding plumage of the territorial and satellite males, although they have much larger internal

Although satellite males are on average slightly smaller and lighter than residents, the nutrition of the chicks does not, as previously thought, influence mating strategy; rather, the inherited mating strategy influences body size. Resident-type chicks will, if provided with the same amount of food, grow heavier than satellite-type chicks. Satellite males do not have to expend energy to defend a territory, and can spend more time foraging, so they do not need to be as bulky as the residents; indeed, since they fly more, there would be a physiological cost to additional weight.

A third type of male was first described in 2006; this is a permanent female mimic, the first such reported for a bird. About 1% of males are small, intermediate in size between males and females, and do not grow the elaborate breeding plumage of the territorial and satellite males, although they have much larger internal testes

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoster ...

than the ruffed males. Although the males of most lekking bird species have relatively small testes for their size, male ruffs have the most disproportionately large testes of any bird.Birkhead (2011) p. 323.

This cryptic male, or "faeder" (Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

"father") obtains access to mating territories together with the females, and "steals" matings when the females crouch to solicit copulation. The faeder moults into the prenuptial male plumage with striped feathers, but does not go on to develop the ornamental feathers of the normal male. As described above, this stage is thought to show the original male breeding plumage, before other male types evolved. A faeder can be distinguished in the hand by its wing length, which is intermediate between those of displaying males and females. Despite their feminine appearance, the faeders migrate with the larger 'normal' lekking males and spend the winter with them.

The faeders are sometimes mounted by independent or satellite males, but are as often "on top" in homosexual mountings as the ruffed males, suggesting that their true identity is known by the other males. Females never mount males. Females often seem to prefer mating with faeders to copulation with normal males, and normal males also copulate with faeders (and ''vice versa'') relatively more often than with females. The homosexual copulations may attract females to the lek, like the presence of satellite males.

Not all mating takes place at the lek, since only a minority of the males attend an active lek. As alternative strategies, males can also directly pursue females ("following") or wait for them as they approached good feeding sites ("intercepting"). Males switched between the three tactics, being more likely to attend a lek when the copulation rate the previous day was high or when fewer females were available after nesting had started. Lekking rates were low in cold weather early in the season when off-lek males spent most of their time feeding.

The level of polyandry

Polyandry (; ) is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wives ...

in the ruff is the highest known for any avian lekking species and for any shorebird. More than half of female ruffs mate with, and have clutches fertilised by, more than one male, and individual females mate with males of both main behavioural morphs more often than expected by chance. In lekking species, females can choose mates without risking the loss of support from males in nesting and rearing chicks, since the males take no part in raising the brood anyway. In the absence of this cost, if polyandry is advantageous, it would be expected to occur at a higher rate in lekking than among pair-bonded species.

Nesting and survival

The nest is a shallow ground scrape lined with grass leaves and stems, and concealed in marsh plants or tall grass up to from the lek. Nesting is solitary, although several females may lay in the general vicinity of a lek. The eggs are slightly glossy, green or olive, and marked with dark blotches; they are laid from mid-March to early June depending on latitude.

The typical clutch is four eggs, each egg measuring in size and weighing of which 5% is shell. Incubation is by the female alone, and the time to hatching is 20–23 days, with a further 25–28 days to fledging. The

The nest is a shallow ground scrape lined with grass leaves and stems, and concealed in marsh plants or tall grass up to from the lek. Nesting is solitary, although several females may lay in the general vicinity of a lek. The eggs are slightly glossy, green or olive, and marked with dark blotches; they are laid from mid-March to early June depending on latitude.

The typical clutch is four eggs, each egg measuring in size and weighing of which 5% is shell. Incubation is by the female alone, and the time to hatching is 20–23 days, with a further 25–28 days to fledging. The precocial

In biology, altricial species are those in which the young are underdeveloped at the time of birth, but with the aid of their parents mature after birth. Precocial species are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the mome ...

chicks have buff and chestnut down, streaked and barred with black, and frosted with white; they feed themselves on a variety of small invertebrates, but are brooded by the female. One brood is raised each year.

Ruffs often show a pronounced inequality in the numbers of each sex. A study of juveniles in Finland found that only 34% were males and 1% were faeders. It appears that females produce a larger proportion of males at the egg stage when they are in poor physical condition. When females are in better condition, any bias in the sex ratio is smaller or absent.

Predators of waders breeding in wet grasslands include birds such as large gulls, common raven

The common raven (''Corvus corax'') is a large all-black passerine bird. It is the most widely distributed of all corvids, found across the Northern Hemisphere. It is a raven known by many names at the subspecies level; there are at least ...

, carrion

Carrion () is the decaying flesh of dead animals, including human flesh.

Overview

Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters (or scavengers) include crows, vultures, c ...

and hooded crow

The hooded crow (''Corvus cornix''), also called the scald-crow or hoodie, is a Eurasian bird species in the genus ''Corvus''. Widely distributed, it is found across Northern, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe, as well as parts of the Middle Eas ...

s, and great

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

and Arctic skua

The parasitic jaeger (''Stercorarius parasiticus''), also known as the Arctic skua, Arctic jaeger or parasitic skua, is a seabird in the skua family Stercorariidae. It is a migratory species that breeds in Northern Scandinavia, Scotland, Iceland ...

s; foxes occasionally take waders, and the impact of feral cats and stoats is unknown. Overgrazing can increase predation by making nests easier to find. In captivity, the main causes of chick mortality were stress-related sudden death and twisted neck syndrome. Adults seem to show little evidence of external parasites, but may have significant levels of disease on their tropical wintering grounds, including avian malaria

Avian malaria is a parasitic disease of birds, caused by parasite species belonging to the genera '' Plasmodium'' and '' Hemoproteus'' (phylum Apicomplexa, class Haemosporidia, family Plasmoiidae). The disease is transmitted by a dipteran vecto ...

in their inland freshwater habitats, and so they might be expected to invest strongly in their immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

s; however, a 2006 study that analysed the blood of migrating ruffs intercepted in Friesland

Friesland (, ; official fry, Fryslân ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen, northwest of Drenthe and Overijssel, north of ...

showed that this bird actually has unexplained low levels of immune responses on at least one measure of resistance. The ruff can breed from its second year, and the average lifespan for birds that have passed the chick stage is about 4.4 years, although a Finnish bird lived to a record 13 years and 11 months.

Feeding

The ruff normally feeds using a steady walk and pecking action, selecting food items by sight, but it will also wade deeply and submerge its head. On saline lakes in East Africa it often swims like aphalarope

__NOTOC__

A phalarope is any of three living species of slender-necked shorebirds in the genus ''Phalaropus'' of the bird family Scolopacidae.

Phalaropes are close relatives of the shanks and tattlers, the ''Actitis'' and Terek sandpipers, a ...

, picking items off the surface. It will feed at night as well as during the day. It is thought that Ruff use both visual and auditory cues to find prey. When feeding, the ruff frequently raises its back feathers, producing a loose pointed peak on the back; this habit is shared only by the black-tailed godwit.

During the breeding season, the ruff’s diet consists almost exclusively of the adults and larva of terrestrial and aquatic insects such as beetles and flies. On migration and during the winter, the ruff eats insects (including caddis flies, water-beetles,

During the breeding season, the ruff’s diet consists almost exclusively of the adults and larva of terrestrial and aquatic insects such as beetles and flies. On migration and during the winter, the ruff eats insects (including caddis flies, water-beetles, mayflies

Mayflies (also known as shadflies or fishflies in Canada and the upper Midwestern United States, as Canadian soldiers in the American Great Lakes region, and as up-winged flies in the United Kingdom) are aquatic insects belonging to the order ...

and grasshoppers), crustaceans, spiders, molluscs, worms, frogs, small fish, and also the seeds of rice and other cereals, sedges, grasses and aquatic plants. Migrating birds in Italy varied their diet according to what was available at each stopover site. Green aquatic plant material, spilt rice and maize, flies and beetles were found, along with varying amounts of grit. On the main wintering grounds in West Africa, rice is a favoured food during the later part of the season as the ricefields dry out.

Just before migration, the ruff increases its body mass at a rate of about 1% a day, much slower than the bar-tailed godwits breeding in Alaska, which fatten at four times that rate. This is thought to be because the godwit cannot use refuelling areas to feed on its trans-Pacific flight, whereas the ruff is able to make regular stops and take in food during overland migration. For the same reason, the ruff does not physiologically shrink its digestive organs to reduce bodyweight before migrating, unlike the godwit.

Relationship with humans

Ruffs were formerly trapped for food in England in large numbers; on one occasion, 2,400 were served at Archbishop Neville's enthronement banquet in 1465. The birds were netted while lekking, sometimes being fattened with bread, milk and seed in holding pens before preparation for the table.

Ruffs were formerly trapped for food in England in large numbers; on one occasion, 2,400 were served at Archbishop Neville's enthronement banquet in 1465. The birds were netted while lekking, sometimes being fattened with bread, milk and seed in holding pens before preparation for the table.

...if expedition is required, sugar is added, which will make them in a fortnight's time a lump of fat: they then sell for two Shillings or half-a-crown a piece… The method of killing them is by cutting off their head with a pair of scissars, the quantity of blood that issues is very great, considering the size of the bird. They are dressed like the Woodcock, with their intestines; and, when killed at the critical time, say the Epicures, are reckoned the most delicious of all morsels.The heavy toll on breeding birds, together with loss of habitat through drainage and collection by nineteenth-century trophy hunters and egg collectors, meant that the species became almost extinct in England by the 1880s, although recolonisation in small numbers has occurred since 1963. The draining of wetlands from the 1800s onwards in southern Sweden has resulted in the ruff's disappearance from many areas there, although it remains common in the north of the country. The use of

insecticide

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to b ...

s and draining of wetlands has led to a decrease in the number of ruff in Denmark since the early 1900s. There are still areas where the ruff and other wetland birds are hunted legally or otherwise for food. A large-scale example is the capture of more than one million waterbirds (including ruffs) in a single year from Lake Chilwa

Lake Chilwa is the second-largest lake in Malawi after Lake Malawi. It is in eastern Zomba District, near the border with Mozambique. Approximately 60 km long and 40 km wide, the lake is surrounded by extensive wetlands. There is an isla ...

in Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast ...

.

Although this bird eats rice on the wintering grounds, where it can make up nearly 40% of its diet, it takes mainly waste and residues from cropping and threshing, not harvestable grain. It has sometimes been viewed as a pest, but the deeper water and presence of invertebrate prey in the economically important early winter period means that the wader has little effect on crop yield.

Conservation status

The ruff has a large range, estimated at 1–10 million square kilometres (0.38–3.8 million square miles) and a population of at least 2,000,000 birds. The European population of 200,000–510,000 pairs, occupying more than half of the total breeding range, seems to have declined by up to 30% over ten years, but this may reflect geographical changes in breeding populations. The Ruff was last assessed in 2016 on a global scale, and is listed as aleast concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

species. In 2021, the IUCN assessed the European population of the ruff as near-threatened

A near-threatened species is a species which has been categorized as "Near Threatened" (NT) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as that may be vulnerable to endangerment in the near future, but it does not currently qualify fo ...

, which could later reflect an uplisting of the species.

The most important breeding populations in Europe, in Russia and Sweden are stable, and the breeding range in Norway has expanded to the south, but populations have more than halved in Finland, Estonia, Poland, Latvia and The Netherlands. Although the small populations in these countries are of limited overall significance, the decline is a continuation of trend towards range contraction that has occurred over the last two centuries. The drop in numbers in Europe has been attributed to drainage, increased fertiliser use, the loss of formerly mown or grazed breeding sites and over-hunting.

Fossils from the

The most important breeding populations in Europe, in Russia and Sweden are stable, and the breeding range in Norway has expanded to the south, but populations have more than halved in Finland, Estonia, Poland, Latvia and The Netherlands. Although the small populations in these countries are of limited overall significance, the decline is a continuation of trend towards range contraction that has occurred over the last two centuries. The drop in numbers in Europe has been attributed to drainage, increased fertiliser use, the loss of formerly mown or grazed breeding sites and over-hunting.

Fossils from the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

suggest that this species bred further south in Europe in the cool periods between glaciations than it does now. Its sensitivity to changing climate as well as to water table levels and the speed of vegetation growth has led to suggestions that its range is affected by global warming, and the ruff might act as an indicator species for monitoring climate change. Potential threats to this species may also include outbreaks of diseases to which it is susceptible such as influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, botulism

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum''. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, feeling tired, and trouble speaking. This may then be followed by weakne ...

and avian malaria

Avian malaria is a parasitic disease of birds, caused by parasite species belonging to the genera '' Plasmodium'' and '' Hemoproteus'' (phylum Apicomplexa, class Haemosporidia, family Plasmoiidae). The disease is transmitted by a dipteran vecto ...

.

The ruff is one of the species to which the ''Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds

The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, or African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) is an independent international treaty developed under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme's Conventio ...

'' (AEWA) applies, where it is allocated to category 2c; that is, the populations in need of special attention as they are showing "significant long-term decline" in much of its range. This commits signatories to regulate the taking of listed species or their eggs, to establish protected areas to conserve habitats for the listed species, to regulate hunting and to monitor the populations of the birds concerned.

Biology of variation among males

The ruff has three male forms, which differ in mating behaviour and in appearance: the typical territorial males which have a dark neck ruff, satellite males which have a white neck ruff, and the very rare cryptic males known as "faeders" which have female-like plumage. The behaviour and appearance of each individual male remain constant through its adult life, and are determined by a simple genetic polymorphism. Territorial behaviour and appearance is

The ruff has three male forms, which differ in mating behaviour and in appearance: the typical territorial males which have a dark neck ruff, satellite males which have a white neck ruff, and the very rare cryptic males known as "faeders" which have female-like plumage. The behaviour and appearance of each individual male remain constant through its adult life, and are determined by a simple genetic polymorphism. Territorial behaviour and appearance is recessive

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

to satellite behaviour and appearance, while preliminary research results suggest that the faeder characteristics are genetically controlled by a single dominant gene. It was originally thought that the difference between territorial and satellite males was due to a sex-linked genetic factor, but in fact the genetic locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

relevant for the mating strategy is located on an autosome

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosome, allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in au ...

, or non-sex chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

. That means that both sexes can carry the two different forms of the gene, not just males. The female does not normally show evidence of her genetic type, but when females are given testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone and anabolic steroid in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testes and prostate, as well as promoting secondar ...

implants, they display the male behaviour corresponding to their genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

. This testosterone-linked behaviour is unusual in birds, where external sexual characteristics are normally determined by the presence or absence of oestrogen

Estrogen or oestrogen is a category of sex hormone responsible for the development and regulation of the female reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics. There are three major endogenous estrogens that have estrogenic hormonal acti ...

.Birkhead (2011) pp. 282–286.

In 2016, two studies further pinpointed the responsible region to chromosome 11 and a 4.5- Mb covering chromosomal rearrangement. The scientists were able to show that the first genetic change happened 3.8 million years ago on the resident chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

, when a part of it broke off and was reintroduced in the wrong direction. This inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

created the faeder allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

. About 500,000 years ago another rare recombination event of faeder and resident allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

in the very same inverted region led to the satellite allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

. The 4.5 Mb inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

covers 90 genes, one of them is the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

coding gene N- CENPN

Centromere protein N is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CENPN'' gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''b ...

-, which is located exactly at one of the inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

breakpoints. The inactivation of the gene has severe deleterious effects and pedigree data of a captive ruff colony suggests that the inversion is homozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

lethal

Lethality (also called deadliness or perniciousness) is how capable something is of causing death. Most often it is used when referring to diseases, chemical weapons, biological weapons, or their toxic chemical components. The use of this ter ...

. Over the course of the past 3.8 million years, further mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

s have accumulated within the inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

i.e. three deletions ranging from 3.3 to 17.6 kb. Two of these deletions remove evolutionary highly conserved elements close to two genes- HSD17B2 and SDR42E1-both holding important roles in metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

of steroid hormone

A steroid hormone is a steroid that acts as a hormone. Steroid hormones can be grouped into two classes: corticosteroids (typically made in the adrenal cortex, hence ''cortico-'') and sex steroids (typically made in the gonads or placenta). Wi ...

s. Hormone measurements around mating time showed that whereas residents have a sharp increase of testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone and anabolic steroid in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testes and prostate, as well as promoting secondar ...

, faeders and satellites only experience higher androstenedione levels, a substance which is considered an intermediate in testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone and anabolic steroid in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testes and prostate, as well as promoting secondar ...

biosynthesis. The authors conclude that one or more of the deletions act as a ''cis

Cis or cis- may refer to:

Places

* Cis, Trentino, in Italy

* In Poland:

** Cis, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, south-central

** Cis, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, north

Math, science and biology

* cis (mathematics) (cis(''θ'')), a trigonome ...

'' -acting regulatory mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

which is altering the expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

of one or both genes and eventually contributes to the different male phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

s and behaviour.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Ruff species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

* Ruffs on postage stamps

www.birdtheme.org

an

Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.0 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

* * * * * * * {{Authority control Calidris Wading birds Birds of Russia Birds of Scandinavia Birds of Africa Birds described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus