Ruairí Ó Brádaigh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh (; born Peter Roger Casement Brady; 2 October 1932 – 5 June 2013) was an

Ó Brádaigh believed RSF to be the sole legitimate continuation of the pre-1986 Sinn Féin, arguing that RSF has kept the original Sinn Féin constitution. RSF readopted and enhanced Ó Brádaigh's ''Éire Nua'' policy. His party has had electoral success in local elections only, and few at that, although they currently have one elected Councillor in Connemara, County Galway.

He remained a vociferous opponent of the

Ó Brádaigh believed RSF to be the sole legitimate continuation of the pre-1986 Sinn Féin, arguing that RSF has kept the original Sinn Féin constitution. RSF readopted and enhanced Ó Brádaigh's ''Éire Nua'' policy. His party has had electoral success in local elections only, and few at that, although they currently have one elected Councillor in Connemara, County Galway.

He remained a vociferous opponent of the

Angry clashes break out at O Bradaigh funeral

Irish Independent, 9 June 2013.

', Dec 1970 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh,

', Dec 1970 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, ''Our people, our future'', Dublin 1973 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, ''Dílseacht – The Story of Comdt General Tom Maguire and the Second (All-Ireland) Dáil'', Dublin: Irish Freedom Press, 1997,

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh's speech to the 1986 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis

, CAIN Web Service. *

SWR Interview with Ruairi O'Bradaigh *

with Ruairí Ó Brádaigh on the question of the legitimacy of the

Documentary "Unfinished Business: The Politics of 'Dissident' Irish Republicans."

{{DEFAULTSORT:Obradaigh, Ruairi 1932 births 2013 deaths Alumni of University College Dublin Irish nationalists Irish people of Swiss descent Irish politicians convicted of crimes Irish Republican Army (1922–1969) members Irish republicans Irish republicans imprisoned by non-jury courts Irish republicans interned without trial Leaders of Sinn Féin Members of the 16th Dáil People from County Longford Provisional Irish Republican Army members Republican Sinn Féin members Republicans imprisoned during the Northern Ireland conflict Sinn Féin TDs (post-1923) People educated at St Mel's College

Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

political and military leader. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief t ...

(IRA) from 1958 to 1959 and again from 1960 to 1962, president of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

from 1970 to 1983, and president of Republican Sinn Féin

Republican Sinn Féin or RSF ( ga, Sinn Féin Poblachtach) is an Irish republican political party in Ireland. RSF claims to be heirs of the Sinn Féin party founded in 1905 and took its present form in 1986 following a split in Sinn Féin. RS ...

from 1987 to 2009.

Early life

Ó Brádaigh, born Peter Roger Casement Brady, was born into a middle-class republican family inLongford

Longford () is the county town of County Longford in Ireland. It has a population of 10,008 according to the 2016 census. It is the biggest town in the county and about one third of the county's population lives there. Longford lies at the meet ...

that lived in a duplex home on Battery Road. His father, Matt Brady, was an IRA volunteer who was severely wounded in an encounter with the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

in 1919. His mother, May Caffrey, was a Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan (; literally "The Women's Council" but calling themselves The Irishwomen's Council in English), abbreviated C na mB, is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and di ...

volunteer and graduate of University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a collegiate university, member institution of the National University of Ireland ...

, class of 1922, with a degree in commerce. His maternal grandmother was a French-speaking Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internati ...

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

. His father died when he was ten, and was given a paramilitary funeral led by his former IRA colleagues. His mother, prominent as the Secretary for the County Longford Board of Health, lived until 1974. Ó Brádaigh was educated at Melview National School at primary level and attended secondary school at St. Mel's College

St Mel's College is an all-boys secondary school in Longford, Ireland.

History

The college opened in September 1865 with 48 boarders and 20 dayboys. The architect was Than Ourke with a total cost of 16,000 euro. In the beginning, it was actua ...

, leaving in 1950, and University College Dublin, from where he graduated in 1954 with a commerce degree ( BComm), like his mother, and certification in the teaching of the Irish language

Irish (an Caighdeán Oifigiúil, Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic languages, Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European lang ...

. That year he took a job teaching Irish at Roscommon Vocational School in Roscommon

Roscommon (; ) is the county town and the largest town in County Roscommon in Ireland. It is roughly in the centre of Ireland, near the meeting of the N60, N61 and N63 roads.

The name Roscommon is derived from Coman mac Faelchon who bui ...

.

Ó Brádaigh was a deeply religious Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

who refrained from smoking or drinking.

Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army

He joinedSinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

in 1950. While at university, in 1951, he joined the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief t ...

. In September 1951, he marched with the IRA at the unveiling of the Seán Russell

Seán Russell (13 October 1893 – 14 August 1940) was an Irish republican who participated in the Easter Rising of 1916, held senior positions in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and Irish Civil War, and was Chief ...

monument in Fairview Park, Dublin

Fairview () is an inner coastal suburb of Dublin in Ireland, in the jurisdiction of Dublin City Council and in the city's D03 postal district. Part of the area forms Fairview Park, a recreational amenity laid-out on land reclaimed from the sea. ...

. A teacher by profession, he was also a Training Officer for the IRA. In 1954, he was appointed to the Military Council of the IRA, a subcommittee set up by the IRA Army Council

The IRA Army Council was the decision-making body of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, a paramilitary group dedicated to bringing about independence to the whole island of Ireland and the end of the Union between Northern Ireland and Great ...

in 1950 to plan a military campaign against Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Roy ...

barracks in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

.

On 13 August 1955, Ó Brádaigh led a ten-member IRA group in an arms raid on Hazebrouck Barracks, near Arborfield

Arborfield is a village on the A327 road in Berkshire about south-east of Reading, about west of Wokingham. It lies in the civil parish of Arborfield and Newland in the Borough of Wokingham, about west of its sister village of Arborfield Cro ...

, Berkshire. It was a depot for the No. 5 Radar Training Battalion of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. It was the biggest IRA arms raid in Britain and netted 48,000 rounds of .303 ammunition, 38,000 9 mm rounds, 1,300 rounds for .380 weapons, and 1,300 .22 rounds. In addition, a selection of arms were seized, including 55 Sten

The STEN (or Sten gun) is a family of British submachine guns chambered in 9×19mm which were used extensively by British and Commonwealth forces throughout World War II and the Korean War. They had a simple design and very low production cost ...

guns, two Bren

The Bren gun was a series of light machine guns (LMG) made by Britain in the 1930s and used in various roles until 1992. While best known for its role as the British and Commonwealth forces' primary infantry LMG in World War II, it was also used ...

guns, two .303 rifles and one .38 pistol. Most if not all of the weapons were recovered in a relatively short period of time. A van, travelling too fast, was stopped by the police and IRA personnel were arrested. Careful police work led to weapons that had been transported in a second van and stored in London.

The IRA Border Campaign commenced on 12 December 1956. As an IRA General Headquarters Staff (GHQ) officer, Ó Brádaigh was responsible for training the Teeling Column (one of the four armed units prepared for the Campaign) in the west of Ireland. During the Campaign, he served as second-in-command of the Teeling Column. On 30 December 1956, he partook in the Teeling Column attack on Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Roy ...

barracks in Derrylin, County Fermanagh

County Fermanagh ( ; ) is one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the six counties of Northern Ireland.

The county covers an area of 1,691 km2 (653 sq mi) and has a population of 61,805 a ...

. RUC Constable John Scally was killed in the attack; Scally was the first fatality of the new IRA campaign. Ó Brádaigh and others were arrested by the Garda Síochána across the border the day after the attack, in County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; gle, Contae an Chabháin) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Ulster and is part of the Border Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is based on the historic Gaelic territory of East Breffny (''Bréifn ...

. They were tried and jailed for six months in Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, Príosún Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History

...

for failing to account for their whereabouts.

Although a prisoner, he was elected a Sinn Féin Teachta Dála

A Teachta Dála ( , ; plural ), abbreviated as TD (plural ''TDanna'' in Irish language, Irish, TDs in English), is a member of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas, Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament). It is the equivalent of terms s ...

(TD) for the Longford–Westmeath constituency at the 1957 Irish general election

The 1957 Irish general election to the 16th Dáil was held on Tuesday, 5 March, following a dissolution of the 15th Dáil on 12 February by President Seán T. O'Kelly on the request of Taoiseach John A. Costello on 4 February. It was the lon ...

, winning 5,506 votes (14.1%). Running on an abstentionist ticket, Sinn Féin won four seats which went to Ó Brádaigh, Eighneachán Ó hAnnluain, John Joe McGirl

John Joe McGirl (25 March 1921 – 8 December 1988) was an Irish republican, a Sinn Féin politician, and a former chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Biography

Anti-Treaty IRA

Born and raised in Ballinamore, County Leitrim, McGi ...

and John Joe Rice. They refused to recognise the authority of Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland r ...

and stated they would only take a seat in an all-Ireland parliament—if it had been possible for them to do so. Ó Brádaigh did not retain his seat at the 1961 Irish general election

The 1961 Irish general election to the 17th Dáil was held on Wednesday, 4 October, following the dissolution of the 16th Dáil on 15 September by President Éamon de Valera on the request of Taoiseach Seán Lemass. The general election took ...

, and his vote fell to 2,598 (7.61%).

Upon completing his prison sentence, he was immediately interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

at the Curragh Military Prison, along with other republicans. On 27 September 1958, Ó Brádaigh escaped from the camp along with Dáithí Ó Conaill. While a football match was in progress, the pair cut through a wire fence and crept from the camp under a camouflage grass blanket and went "on the run". This was an official escape, authorised by the officer commanding of the IRA internees, Tomás Óg Mac Curtain Tomás may refer to:

* Tomás (given name)

* Tomás (surname) Tomás is a Spanish and Portuguese surname, equivalent of ''Thomas''.

It may refer to:

* Antonio Tomás (born 1985), professional Spanish footballer

* Belarmino Tomás (1892–1950), ...

. He was the first Sinn Féin TD on the run since the 1920s.

That October, Ó Brádaigh became the IRA Chief of Staff, a position he held until May 1959, when an IRA Convention elected Sean Cronin as C/S; Ó Brádaigh became Cronin's adjutant general. Ó Brádaigh was arrested in November 1959, refused to answer questions, and was jailed under the Offences against the State Act in Mountjoy. He was released from Mountjoy in May 1960 and, after Cronin was arrested, he again became C/S. Although he has always emphasised that it was a collective declaration, he was the primary author of the statement ending the IRA Border Campaign in 1962. At the IRA 1962 Convention he indicated that he was not interested in continuing as chief of staff.

After his arrest in December 1956, he took a leave from teaching at Roscommon Vocational School. He was re-instated and began teaching again in late 1962, just after he was succeeded by Cathal Goulding in the position of Chief of Staff of the IRA. He remained an active member of Sinn Féin and was also a member of the IRA Army Council throughout the decade.

In the 1966 United Kingdom general election

The 1966 United Kingdom general election was held on 31 March 1966. The result was a landslide victory for the Labour Party led by incumbent Prime Minister Harold Wilson.

Wilson decided to call a snap election since his government, elected a m ...

, he ran as an Independent Republican candidate in the Fermanagh and South Tyrone constituency, polling 10,370 votes, or 19.1% of the valid poll. He failed to be elected.

Leader of Provisional Sinn Féin

1970–73

He opposed the decision of the IRA and Sinn Féin to drop abstentionism and to recognise the Westminster parliament in London, the Stormont parliament inBelfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

and the Leinster House

Leinster House ( ga, Teach Laighean) is the seat of the Oireachtas, the parliament of Ireland. Originally, it was the ducal palace of the Dukes of Leinster. Since 1922, it is a complex of buildings, of which the former ducal palace is the core, ...

parliament in 1969/1970. On 11 January 1970, along with Seán Mac Stíofáin, he led the walkout from the 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (party convention) after the majority voted to end the policy of abstentionism (although the vote to change the Sinn Féin constitution failed as a two-thirds majority was required to do so, whereas the motion only achieved the support of a simple majority of delegates' votes). The delegates who walked out reconvened at the Kevin Barry Hall in Parnell Square

Parnell Square () is a Georgian square sited at the northern end of O'Connell Street in the city of Dublin, Ireland. It is in the city's D01 postal district.

Formerly named ''Rutland Square'', it was renamed after Charles Stewart Parnell (1 ...

, Dublin and established Provisional Sinn Féin.

He was voted chairman of the Caretaker Executive of Provisional Sinn Féin. That October, he formally became president of the party. He held this position until 1983. It is also likely that he served on the Army Council or the executive of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reuni ...

until he was seriously injured in a car accident on 1 January 1984. Among those joining him in Provisional Sinn Féin was his brother, Seán Ó Brádaigh, the first Director of Publicity for Provisional Sinn Féin. Seán Ó Brádaigh continued in this position for almost a decade, when he was succeeded by Danny Morrison, who had been editor of ''An Phoblacht

''An Phoblacht'' (Irish pronunciation: ; en, "The Republic") is a formerly weekly, and currently monthly newspaper published by Sinn Féin in Ireland. From early 2018 onwards, ''An Phoblacht'' has moved to a magazine format while remaining a ...

/Republican News''. Sean Ó Brádaigh was the first editor of the paper.

In his presidential address to the 1971 Provisional Sinn Féin Ard Fheis, Ó Brádaigh said that the first step to achieving a United Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

was to make Northern Ireland ungovernable.

On 31 May 1972 he was arrested under the Offences Against the State Act and immediately commenced a hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

. A fortnight later the charges against him were dropped and he was released.

With Dáithí Ó Conaill he developed the '' Éire Nua'' policy, which was launched on 28 June 1972. The policy called for a federal Ireland.

On 3 December 1972, he appeared on the London Weekend Television

London Weekend Television (LWT) (now part of the non-franchised ITV London region) was the ITV network franchise holder for Greater London and the Home Counties at weekends, broadcasting from Fridays at 5.15 pm (7:00 pm from 1968 ...

'' Weekend World'' programme. He was arrested by the Gardaí again on 29 December 1972 and charged in the newly established Special Criminal Court

The Special Criminal Court (SCC; ga, Cúirt Choiriúil Speisialta) is a juryless criminal court in Ireland which tries terrorism and serious organised crime cases.

Legal basis

Article 38 of the Constitution of Ireland empowers the Dáil to ...

with Provisional IRA membership. In January 1973 he was the first person convicted under the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act 1972 and was sentenced to six months in the Curragh Military Prison.

1974–83

In 1974, he testified in person before theUnited States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid ...

regarding the treatment of IRA prisoners in Ireland. He also had a meeting with prominent Irish-American congressman Tip O'Neill

Thomas Phillip "Tip" O'Neill Jr. (December 9, 1912 – January 5, 1994) was an American politician who served as the 47th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1977 to 1987, representing northern Boston, Massachusetts, as ...

. The same year, the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nat ...

revoked his multiple entry visa and have since refused to allow Ó Brádaigh to enter the country. 1975 Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

documents describe Ó Brádaigh as a "national security threat" and a "dedicated revolutionary undeterred by threat or personal risk" and show that the visa ban was requested by the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

and supported by the Dublin government. In 1997, Canadian authorities refused to allow him board a charter flight to Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most pop ...

at Shannon Airport

Shannon Airport ( ga, Aerfort na Sionainne) is an international airport located in County Clare in the Republic of Ireland. It is adjacent to the Shannon Estuary and lies halfway between Ennis and Limerick. The airport is the third busiest ai ...

.

During the May 1974 Ulster Workers' Council

The Ulster Workers' Council was a loyalist workers' organisation set up in Northern Ireland in 1974 as a more formalised successor to the Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW). It was formed by shipyard union leader Harry Murray and initially fa ...

strike, Ó Brádaigh stated that he would like to see "a phased withdrawal of British troops

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkhas ...

over a number of years, in order to avoid a Congo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

situation".

On 10 December 1974, he participated in the Feakle talks between the IRA Army Council and Sinn Féin leadership and the leaders of the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

churches in Ireland. Although the meeting was raided and broken up by the Gardaí, the Protestant churchmen passed on proposals from the IRA leadership to the British government. These proposals called on the British government to declare a commitment to withdraw, the election of an all-Ireland assembly to draft a new constitution and an amnesty for political prisoners.

The IRA subsequently called a "total and complete" ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

intended to last from 22 December to 2 January 1975 to allow the British government to respond to proposals. British government officials also held talks with Ó Brádaigh in his position as president of Sinn Féin from late December to 17 January 1975.

On 10 February 1975, the IRA Army Council, which may have included Ó Brádaigh, unanimously endorsed an open-ended cessation of IRA "hostilities against Crown forces", which became known as the 1975 truce. The IRA Chief of Staff at the time was Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey ( ga, Séamus Ó Tuama; 5 November 1919 – 12 September 1989) was an Irish republican activist, militant, and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.

Biography

Born in Belfast on Marchioness Street,Volunteer Seamus Twomey, 1 ...

, of Belfast. Another member of the Council at this time was probably Billy McKee, of Belfast. Daithi O'Connell, a prominent Southern Republican, was also a member. It is reported in some quarters that the IRA leaders had mistakenly believed they had persuaded the British Government to withdraw from Ireland and the protracted negotiations between themselves and British officials were the preamble to a public declaration of intent to withdraw. In fact, as British government papers now show, the British entertained talks with the IRA in the hope that this would fragment the movement further, and scored several intelligence coups during the talks. It is argued by some that by the time the truce collapsed in late 1975 the Provisional IRA had been severely weakened. This bad faith embittered many in the republican movement, and another ceasefire was not to happen until 1994. In 2005, Ó Brádaigh donated, to the James Hardiman Library of University College, Galway, notes that he had taken during secret meetings in 1975–76 with British representatives. These notes confirm that the British representatives were offering a British withdrawal as a realistic outcome of the meetings. The Republican representatives—Ó Brádaigh, Billy McKee

Billy McKee ( ga, Liam Mac Aoidh; 12 November 1921 – 11 June 2019) was an Irish republican and a founding member and leader of the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

Early life

McKee was born in Belfast on 12 November 1921, and joined the I ...

and one other—felt a responsibility to pursue the opportunity, but were also sceptical of British intentions.

In late December 1976, along with Joe Cahill

, birth_date =

, death_date =

, birth_place = Belfast, Ireland

, death_place = Belfast, Northern Ireland

, image = Joe Cahill.png

, caption = Cahill, early 1990s.

, allegiance = Provisional Irish Republican ...

, he met two representatives of the Ulster Loyalist Central Coordinating Committee, John McKeague and John McClure, at the request of the latter body. Their purpose was to try to find a way to accommodate the ULCCC proposals for an independent Northern Ireland with the Sinn Féin's Éire Nua programme. It was agreed that if this could be done, a joint Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

-Republican approach could then be made to request the British government to leave Ireland. Desmond Boal QC and Seán MacBride

Seán MacBride (26 January 1904 – 15 January 1988) was an Irish Clann na Poblachta politician who served as Minister for External Affairs from 1948 to 1951, Leader of Clann na Poblachta from 1946 to 1965 and Chief of Staff of the IRA from 19 ...

SC were requested and accepted to represent the loyalist and republican positions. For months they had meetings in various places including Paris. The dialogue eventually collapsed when Conor Cruise O'Brien

Donal Conor David Dermot Donat Cruise O'Brien (3 November 1917 – 18 December 2008), often nicknamed "The Cruiser", was an Irish diplomat, politician, writer, historian and academic, who served as Minister for Posts and Telegraphs from 1973 ...

, then Minister for Posts and Telegraphs

The Minister for Posts and Telegraphs ( ga, Aire Poist agus Telegrafa) was the holder of a position in the Government of Ireland (and, earlier, in the Executive Council of the Irish Free State). From 1924 until 1984 – when it was abolished � ...

and vociferous opponent of the Provisional IRA, became aware of it and condemned it on RTÉ Radio

RTÉ Radio is a division of the Irish national broadcasting organisation Raidió Teilifís Éireann. RTÉ Radio broadcasts four analogue channels and five digital channels nationwide.

Founded in January 1926 as 2RN, the first broadcaster in ...

. As the loyalists had insisted on absolute secrecy, they felt unable to continue with the talks as a result.

In the aftermath of the 1975 truce, the Ó Brádaigh/Ó Conaill leadership came under severe criticism from a younger generation of activists from Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

, headed by Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams ( ga, Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2 ...

, who became a vice-president of Sinn Féin in 1978. By the early 1980s, Ó Brádaigh's position as president of Sinn Féin was openly under challenge and the ''Éire Nua'' policy was targeted in an effort to oust him. The policy was rejected at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis and finally removed from the Sinn Féin constitution at the 1982 Ard Fheis. At the following year's ard fheis, Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill resigned from their leadership positions, voicing opposition to the dropping of the Éire Nua policy by the party.

Leader of Republican Sinn Féin

On 2 November 1986, the majority of delegates to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis voted to drop the policy of abstentionism if elected toDáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland r ...

, but not the British House of Commons or the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, thus ending the self-imposed ban on Sinn Féin elected representatives from taking seats at Leinster House

Leinster House ( ga, Teach Laighean) is the seat of the Oireachtas, the parliament of Ireland. Originally, it was the ducal palace of the Dukes of Leinster. Since 1922, it is a complex of buildings, of which the former ducal palace is the core, ...

. Ó Brádaigh and several supporters walked out and immediately set up Republican Sinn Féin

Republican Sinn Féin or RSF ( ga, Sinn Féin Poblachtach) is an Irish republican political party in Ireland. RSF claims to be heirs of the Sinn Féin party founded in 1905 and took its present form in 1986 following a split in Sinn Féin. RS ...

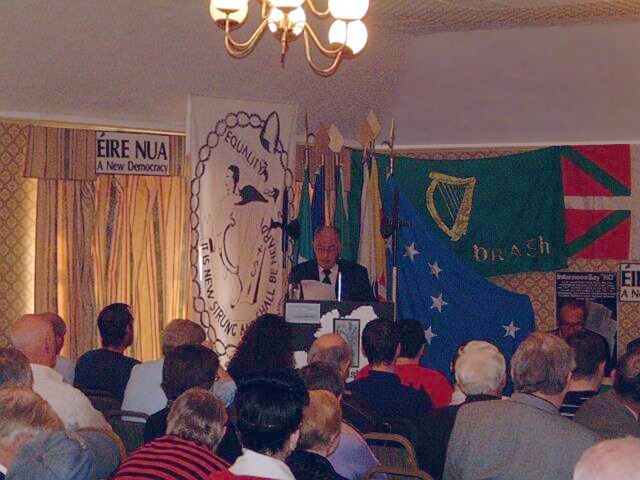

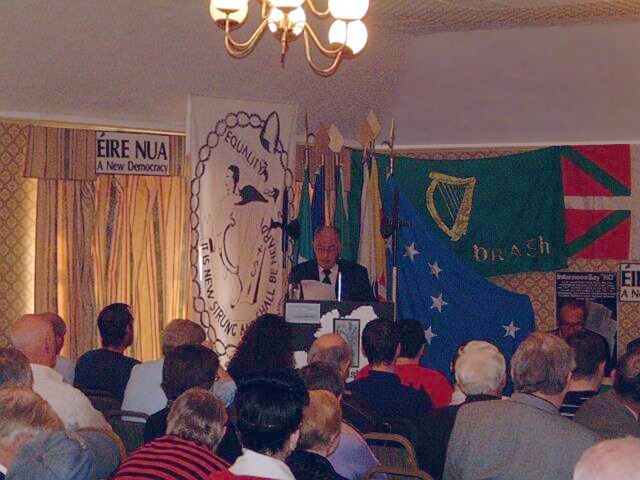

(RSF); more than 100 people assembled at Dublin's West County Hotel and formed the new organisation. As an ordinary member, he had earlier spoken out against the motion (resolution 162) in an impassioned speech. The Continuity IRA became publicly known in 1996. Republican Sinn Féin's relationship with the Continuity IRA is similar to the relationship between Sinn Féin and the Provisional IRA when Ó Brádaigh was Sinn Féin's president.

Ó Brádaigh believed RSF to be the sole legitimate continuation of the pre-1986 Sinn Féin, arguing that RSF has kept the original Sinn Féin constitution. RSF readopted and enhanced Ó Brádaigh's ''Éire Nua'' policy. His party has had electoral success in local elections only, and few at that, although they currently have one elected Councillor in Connemara, County Galway.

He remained a vociferous opponent of the

Ó Brádaigh believed RSF to be the sole legitimate continuation of the pre-1986 Sinn Féin, arguing that RSF has kept the original Sinn Féin constitution. RSF readopted and enhanced Ó Brádaigh's ''Éire Nua'' policy. His party has had electoral success in local elections only, and few at that, although they currently have one elected Councillor in Connemara, County Galway.

He remained a vociferous opponent of the Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in Nor ...

, viewing it as a programme to copperfasten Irish partition and entrench sectarian divisions in the north. He condemned his erstwhile comrades in Provisional Sinn Féin and the Provisional IRA for decommissioning weapons while British troops remain in the country. In his opinion, "the Provo sell-out is the worst yet – unprecedented in Irish history

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quatern ...

". He has condemned the Provisional IRA's decision to seal off a number of its arms dumps as "an overt act of treachery",

"treachery punishable by death" under IRA General Army Order Number 11.

In July 2005, he handed over a portion of his personal political papers detailing discussions between Irish Republican leaders and representatives of the British Government during 1974–1975 to the James Hardiman

James Hardiman (1782–1855), also known as Séamus Ó hArgadáin, was a librarian at Queen's College, Galway.

Hardiman is best remembered for his '' History of the Town and County of Galway'' (1820) and ''Irish Minstrelsy'' (1831), one of the fi ...

Library, National University of Ireland, Galway

The University of Galway ( ga, Ollscoil na Gaillimhe) is a public research university located in the city of Galway, Ireland. A tertiary education and research institution, the university was awarded the full five QS stars for excellence in 201 ...

.

Retirement

In September 2009, Ó Brádaigh announced his retirement as leader of Republican Sinn Féin. His successor was Des Dalton. Ruairí Ó Brádaigh was also a long-standing member of the Celtic League, an organization which fosters cooperation between theCeltic people

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

and promotes the culture, identity and eventual self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It st ...

for the people, in the form of six sovereign states, for the Celtic nations

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who sh ...

- Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlan ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period o ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

and Ireland.

Death

After suffering a period of ill-health, Ó Brádaigh died on 5 June 2013 at Roscommon County Hospital. His funeral was attended by 1,800 mourners includingFine Gael

Fine Gael (, ; English: "Family (or Tribe) of the Irish") is a liberal-conservative and Christian-democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of Dáil � ...

TD Frank Feighan

Frank Feighan (; born 4 July 1962) is an Irish Fine Gael politician who has been a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Sligo–Leitrim constituency since 2020, and previously from 2007 to 2016 for the Roscommon–South Leitrim constituency. He served a ...

and was policed by the Emergency Response Unit and Gardaí in riot gear, for "operational reasons", a show of force believed to have been to deter the republican tradition of firing a three-volley salute of shots over the final place of rest during the graveyard oration. As a result there was some minor scuffles between gardai and mourners.Irish Independent, 9 June 2013.

Writings

* Ruairí Ó Brádaigh,', Dec 1970 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh,

', Dec 1970 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, ''Our people, our future'', Dublin 1973 * Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, ''Dílseacht – The Story of Comdt General Tom Maguire and the Second (All-Ireland) Dáil'', Dublin: Irish Freedom Press, 1997,

See also

* List of members of the Oireachtas imprisoned since 1923References

Sources

*Ruairí Ó Brádaigh's speech to the 1986 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis

, CAIN Web Service. *

SWR Interview with Ruairi O'Bradaigh *

with Ruairí Ó Brádaigh on the question of the legitimacy of the

Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

and its institutions on RTÉ Radio 1

RTÉ Radio 1 ( ga, RTÉ Raidió 1) is an Irish national radio station owned and operated by RTÉ and is the direct descendant of Dublin radio station 2RN, which began broadcasting on a regular basis on 1 January 1926.

The total budget for th ...

's News at One programme, 3 March 2002

Further reading

* Robert W. White, ''Ruairí Ó Brádaigh: The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary'', (Indiana University Press, 2006),External links

Documentary "Unfinished Business: The Politics of 'Dissident' Irish Republicans."

{{DEFAULTSORT:Obradaigh, Ruairi 1932 births 2013 deaths Alumni of University College Dublin Irish nationalists Irish people of Swiss descent Irish politicians convicted of crimes Irish Republican Army (1922–1969) members Irish republicans Irish republicans imprisoned by non-jury courts Irish republicans interned without trial Leaders of Sinn Féin Members of the 16th Dáil People from County Longford Provisional Irish Republican Army members Republican Sinn Féin members Republicans imprisoned during the Northern Ireland conflict Sinn Féin TDs (post-1923) People educated at St Mel's College