Royalist (Spanish American Independence) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The royalists were the people of

The creation of

The creation of

There are two types of units: expeditionary units ( in Spanish: expedicionarios) created in Spain and

There are two types of units: expeditionary units ( in Spanish: expedicionarios) created in Spain and

Hispanic America

The region known as Hispanic America (in Spanish called ''Hispanoamérica'' or ''América Hispana'') and historically as Spanish America (''América Española'') is the portion of the Americas comprising the Spanish-speaking countries of North, ...

(mostly from native and indigenous peoples) and European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

that fought to preserve the integrity of the Spanish monarchy during the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

.

In the early years of the conflict, when King Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

was captive in France, royalists supported the authority in the Americas of the Supreme Central Junta of Spain and the Indies and the Cortes of Cádiz

The Cortes of Cádiz was a revival of the traditional ''Cortes Generales, cortes'' (Spanish parliament), which as an institution had not functioned for many years, but it met as a single body, rather than divided into estates as with previous o ...

that ruled in the King's name during the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

. During the Trienio Liberal in 1820, after the restoration of Ferdinand VII in 1814, the royalists were split between Absolutists, those that supported his insistence to rule under traditional law, and liberals, who sought to reinstate the reforms enacted by the Cortes of Cádiz.

Political evolution

junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

s in Spanish America in 1810 was a direct reaction to developments in Spain during the previous two years. In 1808 Ferdinand VII had been convinced to abdicate

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in his favor, who granted the throne to his brother, Joseph Bonaparte

it, Giuseppe-Napoleone Buonaparte es, José Napoleón Bonaparte

, house = Bonaparte

, father = Carlo Buonaparte

, mother = Letizia Ramolino

, birth_date = 7 January 1768

, birth_place = Corte, Corsica, Republic of ...

. The Supreme Central Junta had led a resistance to Joseph's government and the French occupation of Spain, but suffered a series of reverses resulting in the loss of the northern half of the country. On February 1, 1810, French troops took Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

and gained control of most of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

. The Supreme Junta retreated to Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

and dissolved itself in favor of a Regency Council of Spain and the Indies. As news of this arrived throughout Spanish America during the next three weeks to nine months—depending on time it took goods and people to travel from Spain—political fault lines appeared. Royal officials and Spanish Americans were split between those who supported the idea of maintaining the status quo—that is leaving all the government institutions and officers in place—regardless of the developments in Spain, and those who thought that the time had come to establish local rule, initially through the creation of juntas, in order to preserve the independence of Spanish America from the French or from a rump government in Spain that could no longer legitimately claim to rule a vast empire. It is important to note that, at first, the juntas claimed to carry out their actions in the name of the deposed king and did not formally declare independence. Juntas were successfully established in Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

and New Granada, and there were unsuccessful movements to do so in other regions. A few juntas initially chose to recognize the Regency, nevertheless the creation of juntas challenged the authority of all sitting royal officials and the right of the government in Spain to rule in the Americas.

In the months following the establishment of the Regency, it became clear that Spain was not lost, and furthermore the government was effectively reconstituting itself. The Regency successfully convened the Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies meets ...

, the traditional parliament of the Spanish Monarchy, which in this case included representatives from the Americas. The Regency and Cortes began issuing orders to, and appointing, royal officials throughout the empire. Those who supported the new government came to be called "royalists." Those that supported the idea of maintaining independent juntas called themselves "patriots," and a few among them were proponents of declaring full, formal independence from Spain. As the Cortes instituted liberal reforms and worked on drafting a constitution, a new division appeared among royalists. Conservatives (often called " absolutists" in the historiography) did not want to see any innovations in government, while liberals supported them. These differences would become more acute after the restoration of Ferdinand VII, because the king opted to support the conservative position.

Role of regional rivalry

Regional rivalry also played an important role in the internecine wars that broke out in Spanish America as a result of the juntas. The disappearance of a central, imperial authority—and in some cases of even a local, viceregal authority (as in the cases of New Granada and Río de la Plata)—initiated a prolonged period ofbalkanization

Balkanization is the fragmentation of a larger region or state into smaller regions or states, which may be hostile or uncooperative with one another. It is usually caused by differences of ethnicity, culture, and religion and some other factor ...

in many regions of Spanish America. It was not clear which political units should replace the empire, and there were - among the criollo

Criollo or criolla (Spanish for creole) may refer to:

People

* Criollo people, a social class in the Spanish race-based colonial caste system (the European descendants)

Animals

* Criollo duck, a species of duck native to Central and South Ameri ...

elites at least - no new or old national identities

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

to replace the traditional sense of being Spaniards. The original juntas of 1810 appealed first, to sense of being Spanish, which was juxtaposed against the French threat; second, to a general American identity, which was juxtaposed against the Peninsula which was lost to the French; and third, to a sense of belonging to the local province, the ''patria

Patria may refer to:

Entertainment

* Patria (novel), a 2016 novel by Spanish writer Fernando Aramburu

* Patria (TV series), a 2020 limited television series, based on the novel

* ''Patria'' (serial), a 1917 American serial film

Music

* "Pátri ...

'' in Spanish. More often than not, juntas sought to maintain a province's independence from the capital of the former viceroyalty or captaincy general, as much as from the Peninsula itself. Armed conflicts broke out between the provinces over the question of whether some provinces were to be subordinate to others in the manner that they had been under the crown. This phenomenon was particularly evident in New Granada and Río de la Plata. This rivalry also lead some regions to adopt the opposing political cause from their rivals. Peru seems to have remained strongly royalist in large part because of its rivalry with Río de la Plata, to which it had lost control of Upper Peru when the latter was elevated to a viceroyalty in 1776. The creation of juntas in Río de la Plata allowed Peru to regain formal control of Upper Peru for the duration of the wars.

Restoration of Ferdinand VII

The restoration of Ferdinand VII signified an important change, since most of the political and legal changes done on both sides of the Atlantic—the myriad of juntas, the Cortes in Spain and several of the congresses in the Americas that evolved out of the juntas, and the many constitutions and new legal codes—had been done in his name. Once in Spain Ferdinand VII realized that he had significant support fromconservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in the general population and the hierarchy of the Spanish Catholic Church, and so on May 4, he repudiated the Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitut ...

and ordered the arrest of liberal leaders who had created it on May 10. Ferdinand justified his actions by stating that the Constitution and other changes had been made by a Cortes assembled in his absence and without his consent. He also declared all of the juntas and constitutions written in Spanish America invalid and restored the former law codes and political institutions.

This, in effect, constituted a definitive break with two groups that could have been allies of Ferdinand VII: the autonomous governments, which had not yet declared formal independence, and Spanish liberals who had created a representative government that would fully include the overseas possessions and was seen as an alternative to independence by many in New Spain (today Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

), Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, Venezuela, Quito (Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

), Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, Upper Peru (Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

) and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

.

The provinces of New Granada had maintained independence from Spain since 1810, unlike neighboring Venezuela, where royalists and pro-independence forces had exchanged control of the region several times. To pacify Venezuela and to retake New Granada, Spain organized in 1815 the largest armed force it ever sent to the New World, consisting of 10,500 troops and nearly sixty ships. (See, Spanish reconquest of New Granada

The Spanish Invasion of New Granada in 1815–1816 was part of the Spanish American wars of independence in South America. Shortly after the Napoleonic Wars ended, Ferdinand VII, recently restored to the throne in Spain, decided to send milit ...

). Although this force was crucial in retaking a solidly pro-independence region like New Granada, its soldiers were eventually spread out throughout Venezuela, New Granada, Quito, and Peru and were lost to tropical diseases, diluting their impact on the war. More importantly, the majority of the royalist forces were composed, not of soldiers sent from the peninsula, but of Spanish Americans. Other Spanish Americans were moderates who decided to wait and see what would come out of the restoration of normalcy. In fact in areas of New Spain, Central America and Quito, governors found it expedient to leave the elected constitutional '' ayuntamientos'' in place for several years in order to prevent conflict with the local society. Liberals on both sides of the Atlantic, nevertheless, continued to conspire to bring back a constitutional monarchy, ultimately succeeding in 1820. The most dramatic example of transAtlantic collaboration is perhaps Francisco Javier Mina

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comunitatis'' (father of ...

's expedition to Texas and northern Mexico in 1816 and 1817.

Spanish Americans in royalist areas who were committed to independence had already joined guerrilla movements. Ferdinand's actions did set areas outside of the control of the royalist armies on the path to full independence. The governments of these regions, which had their origins in the juntas of 1810—and even moderates there who had entertained a reconciliation with the crown—now saw the need to separate from Spain, if they were to protect the reforms they had enacted.

Restoration of the Spanish Constitution and independence

Spanish liberals finally had success in forcing Ferdinand VII to restore the Constitution on January 1, 1820, when Rafael Riego headed a rebellion among troops which had been gathered for a large expeditionary force to be sent to the Americas. By March 7, the royal palace in Madrid was surrounded by soldiers under the command of GeneralFrancisco Ballesteros

Francisco Ballesteros (1770 in Zaragoza – 29 June 1832 in Paris) emerged as a career Spanish General during the Peninsular War.

Ballasteros served against the First French Republic in the 1793 War of the Pyrenees. He was dismissed from his ...

, and three days later on March 10, the besieged Ferdinand VII, now a virtual prisoner, agreed to restore the Constitution.

Riego's revolt had two significant effects on the war in the Americas. First in military matters, the large numbers of reinforcements, that were especially needed to retake New Granada and defend the Viceroyalty of Peru, would never arrive. Furthermore, as the royalist situation became more desperate in region after region, the army experienced wholesale defections of units to the patriot side. Second in political matters, the reinstitution of a liberal regime changed the terms under which the Spanish government sought to engage the insurgents. The new government naively assumed that the insurgents were fighting for Spanish liberalism and that the Spanish Constitution could still be the basis of reconciliation between the two sides. Government implemented the Constitution and held elections in the overseas provinces, just as in Spain. It also ordered military commanders to begin armistice negotiations with the insurgents with the promise that they could participate in the restored representative government.

The Spanish Constitution, it turned out, served as the basis for independence in New Spain and Central America, since in the two regions it was a coalition of conservative and liberal royalist leaders who led the establishment of new states. The restoration of the Spanish Constitution and representative government was enthusiastically welcomed in New Spain and Central America. Elections were held, local governments formed and deputies

A legislator (also known as a deputy or lawmaker) is a person who writes and passes laws, especially someone who is a member of a legislature. Legislators are often elected by the people of the state. Legislatures may be supra-national (for ex ...

sent to the Cortes. Among liberals, however, there was fear that the new regime would not last, and among conservatives and the Church, that the new liberal government would expand its reforms and anti-clerical legislation. This climate of instability created the conditions for the two sides to forge an alliance. This alliance coalesced towards the end of 1820 behind Agustín de Iturbide

Agustín de Iturbide (; 27 September 178319 July 1824), full name Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu and also known as Agustín of Mexico, was a Mexican army general and politician. During the Mexican War of Independence, he built a ...

, a colonel in the royal army, who at the time was assigned to destroy the guerrilla forces led by Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

. Instead Iturbide entered into negotiations, which resulted in the Plan of Iguala

The Plan of Iguala, also known as The Plan of the Three Guarantees ("Plan Trigarante") or Act of Independence of North America, was a revolutionary proclamation promulgated on 24 February 1821, in the final stage of the Mexican War of Independenc ...

, which would establish New Spain as an independent kingdom, with Ferdinand VII as its king. With the Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guaran ...

, the highest Spanish official in Mexico approved the Plan of Iguala, and although the Spanish government never ratified this treaty, it did not have the resources to enforce its rejection. Ultimately, it was the royal army in Mexico that ultimately brought about that nation's independence.

Central America gained its independence along with New Spain. The regional elites supported the terms of the Plan of Iguala and orchestrated the union of Central America with the Mexican Empire in 1821. Two years later following Iturbide's downfall, the region, with the exception of Chiapas, peacefully seceded from Mexico in July 1823, establishing the Federal Republic of Central America

The Federal Republic of Central America ( es, República Federal de Centroamérica), originally named the United Provinces of Central America ( es, Provincias Unidas del Centro de América), and sometimes simply called Central America, in it ...

. The new state existed for seventeen years, centrifugal forces pulling the individual provinces apart by 1840.Lynch, ''Spanish American Revolutions'', 333–340. Rodríguez, ''Independence of Spanish America'', 210–213. Kinsbruner, ''Independence in Spanish America'', 100, 146–149.

In South America independence was spurred by the pro-independence fighters that had held out for the past half decade. José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and cent ...

and Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

inadvertently led a continental-wide pincer movement

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pin ...

from southern and northern South America that liberated most of the Spanish American nations on that continent and secured the independence the Southern Cone

The Southern Cone ( es, Cono Sur, pt, Cone Sul) is a geographical and cultural subregion composed of the southernmost areas of South America, mostly south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Traditionally, it covers Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, bou ...

had more or less experienced since 1810. In South America, royalist soldiers, officers (such as Andrés de Santa Cruz

Andrés de Santa Cruz y Calahumana (; 30 November 1792 – 25 September 1865) was a Bolivian general and politician who served as interim president of Peru in 1827, the interim president of Peru from 1836 to 1838 and the sixth president of B ...

) and whole units also began to desert or defect to the patriots in large numbers as the royal army's situation became dire. During the end of 1820 in Venezuela, after Bolívar and Pablo Morillo

Pablo Morillo y Morillo, Count of Cartagena and Marquess of La Puerta, a.k.a. ''El Pacificador'' (The Peace Maker) (5 May 1775 – 27 July 1837) was a Spanish general.

Biography

Morillo was born in Fuentesecas, Zamora, Spain. In 1791 ...

concluded a cease fire, many units crossed lines knowing that Spanish control of the region would not last. The situation repeated itself in Peru from 1822 to 1825 as republican forces slowly advanced there. Unlike in Mexico, however, the top military and political leadership in these parts of South America came from patriot side and not the royalists.

The collapse of the constitutional regime in Spain in 1823 had other implications for the war in South America. Royalist officers, split between liberals and conservatives, fought an internecine war among themselves. General Pedro Antonio Olañeta, commander in Upper Peru, rebelled against the liberal viceroy of Peru, José de la Serna

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

, in 1823. This conflict provided an opportunity for the republican forces under the command of Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second pr ...

to advance, culminating in the Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho ( es, Batalla de Ayacucho, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of South America. In Peru it is co ...

on December 9, 1824. The royal army of Upper Peru surrendered after Olañeta was killed on April 2, 1825. Former royalists, however, played an important part in the creation of Peru and Bolivia. In Bolivia, royalists, like Casimiro Olañeta, nephew of General Olañeta, gathered in a congress and declared the country's independence from Peru. And in Peru after Bolívar's forces left the country in 1827, Peruvian leaders undid many of his political reforms.

Royalist army

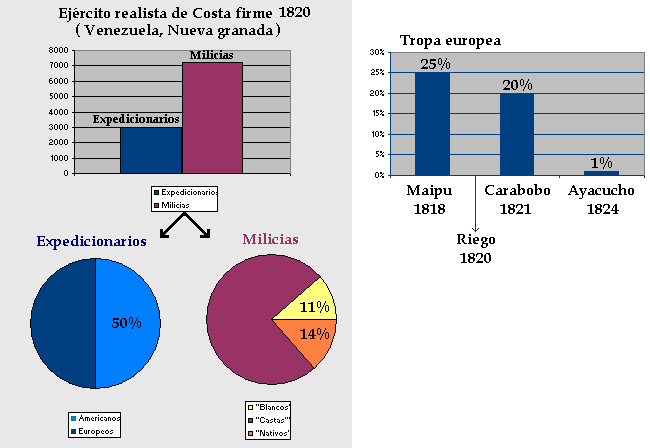

There are two types of units: expeditionary units ( in Spanish: expedicionarios) created in Spain and

There are two types of units: expeditionary units ( in Spanish: expedicionarios) created in Spain and militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s (in Spanish: milicias), units which already existed or were created during the conflict in America. The militias, which were composed wholly of militiamen who were residents or natives of Spanish America, were bolstered by the presence of "veteran units" (or "disciplined militia") composed of Peninsular and Spanish American veterans of Spain's wars in Europe and around the globe. The veteran units were expected to form a core of experienced soldiers in the local defenses, whose expertise would be invaluable to the regular militiamen who often lacked sustained military experience, if any. The veteran units were created in the past century as part of the Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's po ...

to reinforce Spanish America's defenses against the increasing encroachment of other European powers, such as during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

.

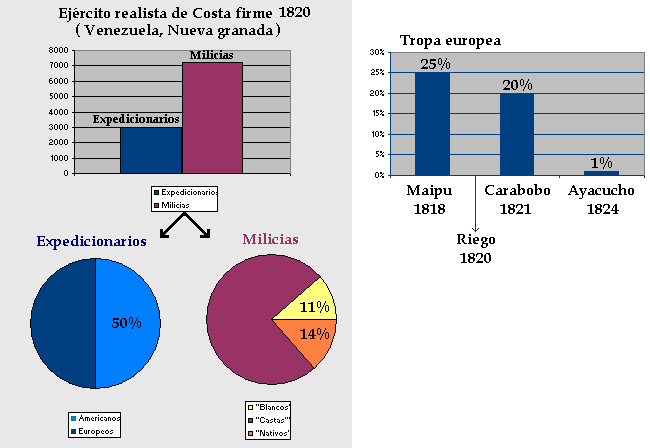

Overall, Europeans formed only about a tenth of the royalist armies in Spanish America, and only about half of the expeditionary units. Since each European soldier casualty

Casualty may refer to:

*Casualty (person), a person who is killed or rendered unfit for service in a war or natural disaster

**Civilian casualty, a non-combatant killed or injured in warfare

* The emergency department of a hospital, also known as ...

was substituted by a Spanish American soldier, over time, there were more and more Spanish American soldiers in the expeditionary units. For example, Pablo Morillo

Pablo Morillo y Morillo, Count of Cartagena and Marquess of La Puerta, a.k.a. ''El Pacificador'' (The Peace Maker) (5 May 1775 – 27 July 1837) was a Spanish general.

Biography

Morillo was born in Fuentesecas, Zamora, Spain. In 1791 ...

, commander in chief in Venezuela and New Granada, reported that he only had 2,000 European soldiers, in other words, only half of the soldiers of his expeditionary force were European. It is estimated that in the Battle of Maipú only a quarter of the royalist forces were European soldiers, in the Battle of Carabobo

The Battle of Carabobo, on 24 June 1821, was fought between independence fighters, led by Venezuelan General Simón Bolívar, and the Royalist forces, led by Spanish Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre. Bolívar's decisive victory at Carabobo led ...

about a fifth, and in the Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho ( es, Batalla de Ayacucho, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of South America. In Peru it is co ...

less than 1% was European.

The American militias reflected the racial make-up of the local population. For example, in 1820 the royalist army in Venezuela had 843 white (''español''), 5,378 Casta and 980 Native

Native may refer to:

People

* Jus soli, citizenship by right of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Native Americans (disambiguation)

In arts and entert ...

soldiers.

The last royalist armed group in what is today Argentina and Chile, the Pincheira brothers

The Pincheira brothers (Spanish: ''Hermanos Pincheira'') was an infamous royalist outlaw group in Chile and Argentina active from 1818 to 1832. The gang fought initially in the Chilean War of Independence as royalist guerrillas during the Guer ...

, was an outlaw gang made of Europeans Spanish, American Spanish, Mestizos and local indigenous peoples. This group was originally based near Chillán

Chillán () is the capital city of the Ñuble Region in the Diguillín Province of Chile located about south of the country's capital, Santiago, near the geographical center of the country. It is the capital of the new Ñuble Region since 6 Sept ...

in Chile but moved later across the Andes to Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

thanks to its alliance with indigenous tribes. In the interior of Patagonia, far from the de facto territory of Chile and the United Provinces, the Pincheira brothers established permanent encampment with thousands of settlers.

Royalist leaders

Naval commanders and last fortresses

See also

*Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

* Spanish expeditionary army order of battle

* Reconquista (Spanish America)

In the struggle for the independence of Spanish America, the Reconquista refers to the period of Colombian and Chilean history, following the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, during which royalist armies were able to gain the upper hand in the Spanish ...

* Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War, often referred to as Tories, Royalists or King's Men at the time. They were opposed by the Patriots, who supporte ...

, the equivalent of the Royalist in Anglo-America

References

Bibliography

*Kenneth J. Andrien and Lyman L. Johnson (1994). ''The Political Economy of Spanish America in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1850''. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press. *Timothy Anna (1983). ''Spain & the Loss of Empire''. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press. *Christon I. Archer (ed.) (2000). ''The Wars of Independence in Spanish America''. Willmington, SR Books. * Benson, Nettie Lee (ed.) (1966). ''Mexico and the Spanish Cortes.'' Austin: University of Texas Press. *Michael P. Costeloe (1986). ''Response to Revolution: Imperial Spain and the Spanish American Revolutions, 1810-1840''. Cambridge University Press. *Jorge I. Domínguez (1980). ''Insurrection or Loyalty: The Breakdown of the Spanish American Empire''. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. *Jay Kinsbruner. ''Independence in Spanish America: Civil Wars, Revolutions, and Underdevelopment'' (Revised edition). Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2000. *John Lynch. ''The Spanish American Revolutions, 1808-1826'' (2nd edition). New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 1986. *Marie Laure Rieu-Millan (1990). ''Los diputados americanos en las Cortes de Cádiz: Igualdad o independencia.'' ( In Spanish.) Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. *Jaime E. Rodríguez O. (1998). ''The Independence of Spanish America''. Cambridge University Press. * Mario Rodríguez (1978). ''The Cádiz Experiment in Central America, 1808 to 1826.'' Berkeley: University of California Press. * Tomás Straka (2000). "La voz de los vencidos. Ideas del partido realista de Caracas, 1810-1821!. Caracas, Universidad Central de Venezuela, {{ISBN, 978-980-00-1771-5 People of the Spanish colonial Americas Spanish American wars of independence Spanish colonization of the Americas Counter-revolutionaries