Royal Prussian Court on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) constituted the German state of

The style "King ''in'' Prussia" was adopted to acknowledge the

The style "King ''in'' Prussia" was adopted to acknowledge the

In 1740 King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) came to the throne. Using the pretext of a 1537 treaty (vetoed by Emperor Ferdinand I) by which parts of

In 1740 King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) came to the throne. Using the pretext of a 1537 treaty (vetoed by Emperor Ferdinand I) by which parts of  Humiliated by the cession of Silesia, Austria worked to secure an alliance with France and Russia (the "

Humiliated by the cession of Silesia, Austria worked to secure an alliance with France and Russia (the "

To the east and south of Prussia, the

To the east and south of Prussia, the

Following the

Following the

Prussia's reward for its part in France's defeat came at the

Prussia's reward for its part in France's defeat came at the

Although Bismarck had a reputation as an unyielding conservative, he initially inclined to seek a compromise over the budget issue. However, William refused to consider it; he viewed defence issues as the crown's personal province. Forced into a policy of confrontation, Bismarck came up with a novel theory. Under the constitution, the king and the parliament were responsible for agreeing on the budget. Bismarck argued that since they had failed to come to an agreement, there was a "hole" in the constitution, and the government had to continue to collect taxes and disburse funds in accordance with the old budget in order to keep functioning. The government thus operated without a new budget from 1862 to 1866, allowing Bismarck to implement William's military reforms.

The liberals violently denounced Bismarck for what they saw as his disregard for the fundamental law of the kingdom. However, Bismarck's real plan was an accommodation with liberalism. Although he had opposed German unification earlier in his career, he had now come to believe it inevitable. To his mind, the conservative forces had to take the lead in the drive toward creating a unified nation in order to keep from being eclipsed. He also believed that the middle-class liberals wanted a unified Germany more than they wanted to break the grip of the traditional forces over society. He thus embarked on a drive to form a united Germany under Prussian leadership, and guided Prussia through three wars which ultimately achieved this goal.

The first of these wars was the

Although Bismarck had a reputation as an unyielding conservative, he initially inclined to seek a compromise over the budget issue. However, William refused to consider it; he viewed defence issues as the crown's personal province. Forced into a policy of confrontation, Bismarck came up with a novel theory. Under the constitution, the king and the parliament were responsible for agreeing on the budget. Bismarck argued that since they had failed to come to an agreement, there was a "hole" in the constitution, and the government had to continue to collect taxes and disburse funds in accordance with the old budget in order to keep functioning. The government thus operated without a new budget from 1862 to 1866, allowing Bismarck to implement William's military reforms.

The liberals violently denounced Bismarck for what they saw as his disregard for the fundamental law of the kingdom. However, Bismarck's real plan was an accommodation with liberalism. Although he had opposed German unification earlier in his career, he had now come to believe it inevitable. To his mind, the conservative forces had to take the lead in the drive toward creating a unified nation in order to keep from being eclipsed. He also believed that the middle-class liberals wanted a unified Germany more than they wanted to break the grip of the traditional forces over society. He thus embarked on a drive to form a united Germany under Prussian leadership, and guided Prussia through three wars which ultimately achieved this goal.

The first of these wars was the  The divided administration of Schleswig and Holstein then became the trigger for the

The divided administration of Schleswig and Holstein then became the trigger for the

The Kingdom of Prussia was an absolute monarchy until the German revolutions of 1848–1849, Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, after which Prussia became a constitutional monarchy and Adolf Heinrich von Arnim-Boitzenburg was appointed as Prussia's first Minister President of Prussia, Minister President. Following Prussia's first constitution, a two-house parliament was formed, called the Landtag of Prussia, Landtag. The lower house, or Prussian House of Representatives was elected by all males over the age of 25 using the

The Kingdom of Prussia was an absolute monarchy until the German revolutions of 1848–1849, Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, after which Prussia became a constitutional monarchy and Adolf Heinrich von Arnim-Boitzenburg was appointed as Prussia's first Minister President of Prussia, Minister President. Following Prussia's first constitution, a two-house parliament was formed, called the Landtag of Prussia, Landtag. The lower house, or Prussian House of Representatives was elected by all males over the age of 25 using the

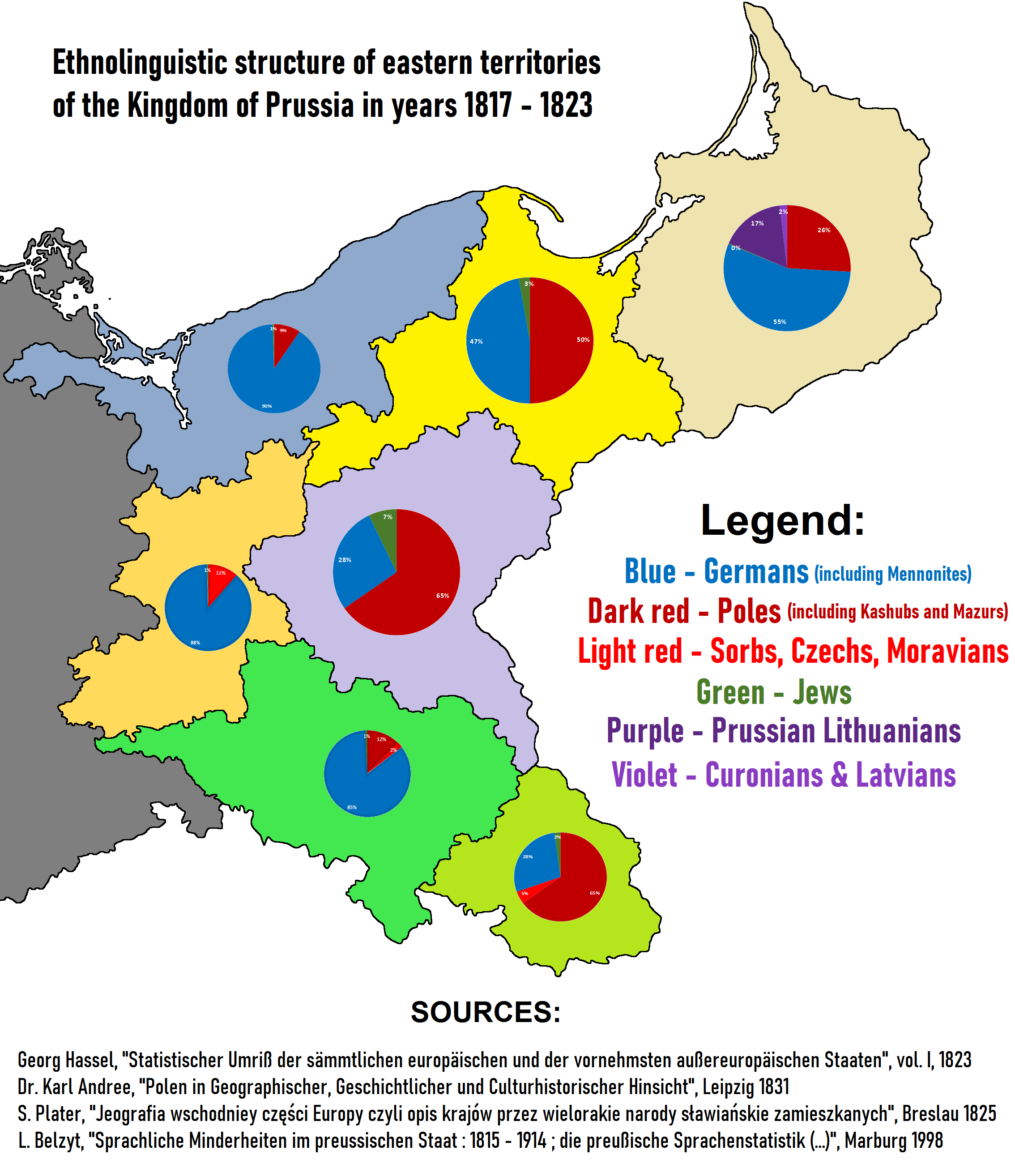

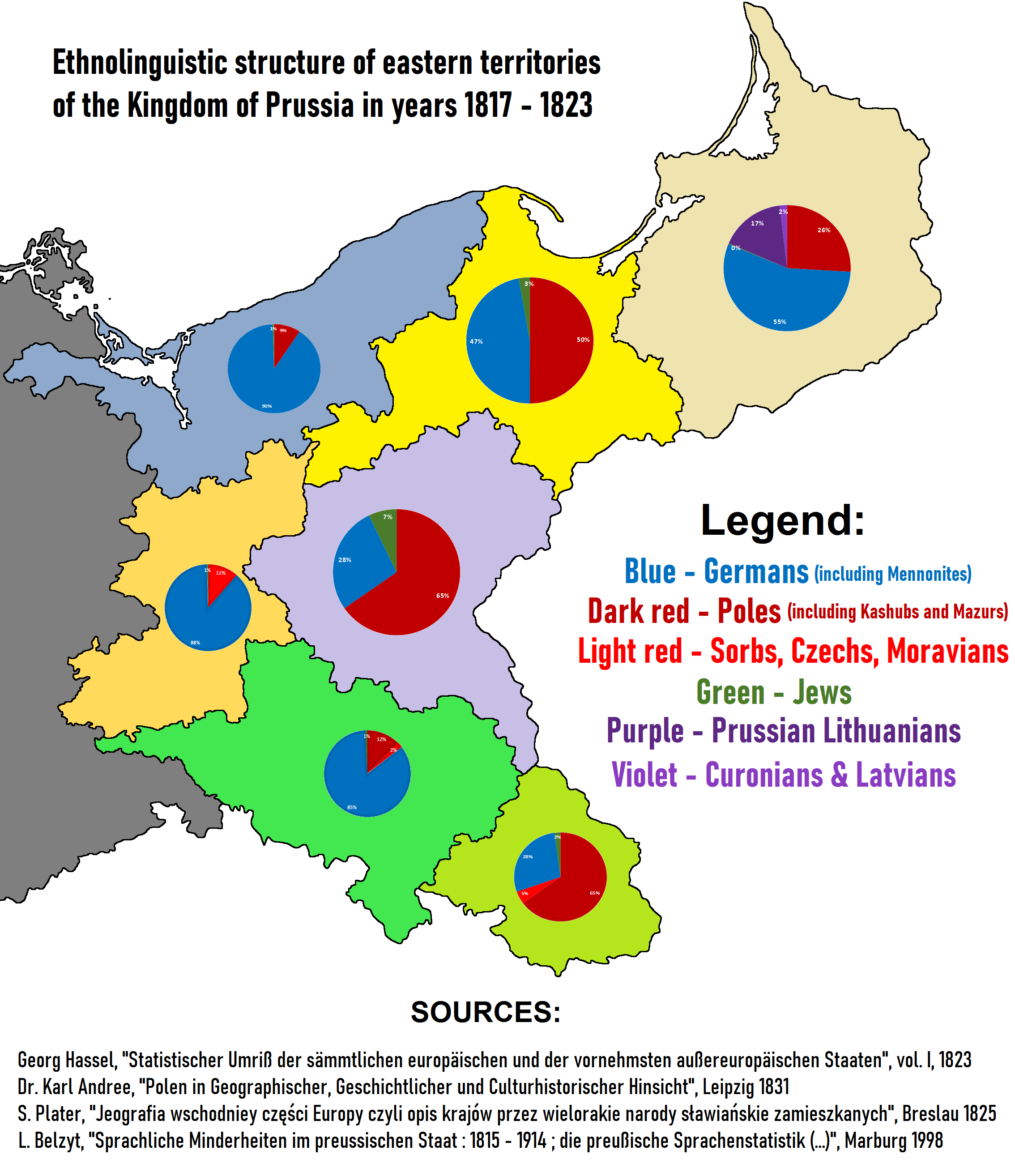

Apart from ethnic Germans the country was inhabited also by Ethnolinguistic group, ethnolinguistic minorities such as Polish people, Poles (including Kashubians, Kashubs in West Prussia and Masurians, Mazurs in East Prussia), Prussian Lithuanians (in East Prussia), Sorbs (in Lusatia), Czechs and Moravians (in Silesia), Danes (in Schleswig), Jews, Frisians, Dutch people, Dutch, Walloons, Russians (in Wojnowo, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Wojnowo), French people, French, Italians, Hungarians and others.

Apart from ethnic Germans the country was inhabited also by Ethnolinguistic group, ethnolinguistic minorities such as Polish people, Poles (including Kashubians, Kashubs in West Prussia and Masurians, Mazurs in East Prussia), Prussian Lithuanians (in East Prussia), Sorbs (in Lusatia), Czechs and Moravians (in Silesia), Danes (in Schleswig), Jews, Frisians, Dutch people, Dutch, Walloons, Russians (in Wojnowo, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Wojnowo), French people, French, Italians, Hungarians and others.

The original core regions of the Kingdom of Prussia were the

The original core regions of the Kingdom of Prussia were the

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R.

Sir John Arthur Ransome Marriott (17 August 1859 – 6 June 1945) was a British educationist, historian, and Conservative member of parliament (MP).

Marriott taught modern history at the University of Oxford from 1884 to 1920. He was an Honor ...

, and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It was the driving force behind the unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federalism, federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with ad ...

in 1866 and was the leading state of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

until its dissolution in 1918. Although it took its name from the region called Prussia, it was based in the Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out o ...

. Its capital was Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

.

The kings of Prussia

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman C ...

were from the House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzol ...

. Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

, predecessor of the kingdom, became a military power under Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg

Frederick William (german: Friedrich Wilhelm; 16 February 1620 – 29 April 1688) was Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, thus ruler of Brandenburg-Prussia, from 1640 until his death in 1688. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he is ...

, known as "The Great Elector". As a kingdom, Prussia continued its rise to power, especially during the reign of Frederick II "the Great".Horn, D. B. "The Youth of Frederick the Great 1712–30." In Frederick the Great and the Rise of Prussia, 9–10. 3rd ed. London: English Universities Press, 1964. Frederick the Great was instrumental in starting the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(1756–1763), holding his own against Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

and establishing Prussia's dominant role among the German states, as well as establishing the country as a European great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

through the victories of the powerful Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

. Prussia made attempts to unify all the German states (excluding the German cantons in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

) under its rule, and whether Austria would be included in such a unified German domain became an ongoing question. After the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

led to the creation of the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, the issue of unifying the German states caused the German revolutions of 1848–1849

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated pro ...

, with representatives from all states attempting to unify under their own constitution. Attempts to create a federation remained unsuccessful and the German Confederation collapsed in 1866 when the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

ensued between its two most powerful member states.

Prussia was subsequently the driving force behind establishing in 1866 the North German Confederation

The North German Confederation (german: Norddeutscher Bund) was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated st ...

, transformed in 1871 into the unified German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and considered the earliest continual legal predecessor of today's Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

. The North German Confederation was seen as more of an alliance of military strength in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War but many of its laws were later used in the German Empire. The German Empire successfully unified all of the German states aside from Austria and Switzerland under Prussian hegemony due to the defeat of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. The war united all the German states against a common enemy, and with the victory came an overwhelming wave of nationalism which changed the opinions of some of those who had been against unification.

With the German Revolution of 1918–1919

The German Revolution or November Revolution (german: Novemberrevolution) was a civil conflict in the German Empire at the end of the First World War that resulted in the replacement of the German federal constitutional monarchy with a dem ...

, the Kingdom of Prussia was transformed into the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domin ...

.

History

Background and establishment

TheHohenzollerns

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenbu ...

were made rulers of the Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out o ...

in 1518. In 1529 the Hohenzollerns secured the reversion of the Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (german: Herzogtum Pommern; pl, Księstwo Pomorskie; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country ha ...

after a series of conflicts, and acquired its eastern part following the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

.

In 1618 the electors of Brandenburg also inherited the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the Prussia (region), region of P ...

, since 1511 ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hohenzollern. In 1525, Albrecht of Brandenburg, the last grand master of the Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

, secularized his territory and converted it into a duchy. It was ruled in a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with Brandenburg, known as "Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

". A full union was not possible, since Brandenburg was still legally part of the Holy Roman Empire and the Duchy of Prussia was a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. The Teutonic Order had paid homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to Poland since 1466, and the Hohenzollerns continued to pay homage after secularizing Ducal Prussia.

In the course of the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia (Russo-Swedish War (1656–1658), 1656–58), Brande ...

, the treaties of Labiau

Polessk (russian: Поле́сск; german: Labiau; lt, Labguva; pl, Labiawa) is a town and the administrative center of Polessky District in Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, located northeast of Kaliningrad, the administrative center of the oblas ...

and Wehlau-Bromberg granted the Hohenzollerns full sovereignty over the Prussian duchy by September 1657.

In return for an alliance against France in the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, the Great Elector's son, Frederick III, was allowed to elevate Prussia to a kingdom in the Crown Treaty {{Short description, 1700 treaty between Brandenburg and Emperor Leopold I

In the Crown Treaty (also called Treaty of the Crown, ''Krontraktat'' in German) signed on 16 November 1700, Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, had ...

of 16 November 1700. Frederick crowned himself "King in Prussia

King ''in'' Prussia (German: ''König in Preußen'') was a title used by the Prussian kings (also in personal union Electors of Brandenburg) from 1701 to 1772. Subsequently, they used the title King ''of'' Prussia (''König von Preußen'').

Th ...

" as Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoller ...

on 18 January 1701. Legally, no kingdoms could exist in the Holy Roman Empire except for Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. However, Frederick took the line that since Prussia had never been part of the empire and the Hohenzollerns were fully sovereign over it, he could elevate Prussia to a kingdom. Emperor Leopold I, keen to secure Frederick's support in the impending War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, acquiesced.

legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts, which is then used in order to help reach a decision or to apply a legal rule. The concept is used almost exclusively in common law jurisdictions, particularly in England and Wales.

Deve ...

that the Hohenzollerns were legally kings only in their former duchy. In Brandenburg and the portions of their domains that were within the Empire, they were still legally only electors under the overlordship of the emperor. However, by this time the emperor's authority was only nominal. The rulers of the empire's various territories acted largely as the rulers of sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

s, and only acknowledged the emperor's suzerainty in a formal way. In addition, the duchy was only the eastern bulk of the region of Prussia; the westernmost fragment constituted the part of Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

east of Vistula, held along with the title ''King of Prussia'' by the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

. While the personal union between Brandenburg and Prussia legally continued until the end of the empire in 1806, from 1701 onward Brandenburg was ''de facto'' treated as an integral part of the kingdom. Since the Hohenzollerns were nominally still subjects of the emperor within the parts of their domains that were part of the empire, they continued to use the additional title of Elector of Brandenburg until the empire was dissolved. It was not until 1772 that the title "King ''of'' Prussia" was adopted, following the acquisition of Royal Prussia in the First Partition of Poland.

1701–1721: Plague and the Great Northern War

The Kingdom of Prussia was still recovering from the devastation of theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

and poor in natural resources. Its territory was disjointed, stretching from the lands of the Duchy of Prussia on the south-east coast of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

to the Hohenzollern heartland of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

, with the exclaves of Cleves

Kleve (; traditional en, Cleves ; nl, Kleef; french: Clèves; es, Cléveris; la, Clivia; Low Rhenish: ''Kleff'') is a town in the Lower Rhine region of northwestern Germany near the Dutch border and the River Rhine. From the 11th century ...

, Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fi ...

and Ravensberg in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. In 1708 about one third of the population of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

died during the Great Northern War plague outbreak

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), many towns and areas around the Baltic Sea and East-Central Europe had a severe outbreak of the plague with a peak from 1708 to 1712. This epidemic was probably part of a pandemic affecting an area from ...

. The bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

reached Prenzlau

Prenzlau (, formerly also Prenzlow) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Uckermark (district), Uckermark District. It is also the centre of the historic Uckermark region.

Geography

The town is located on the Uecker, Ucke ...

in August 1710 but receded before it could reach the capital Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, which was only away.

The Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swedi ...

was the first major conflict in which the Kingdom of Prussia was involved. Starting in 1700, the war involved a coalition led by Tsarist Russia Tsarist Russia may refer to:

* Grand Duchy of Moscow (1480–1547)

*Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721)

*Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of ...

against the dominant North European power at the time, the Swedish Empire

The Swedish Empire was a European great power that exercised territorial control over much of the Baltic region during the 17th and early 18th centuries ( sv, Stormaktstiden, "the Era of Great Power"). The beginning of the empire is usually ta ...

. Crown Prince Frederick William tried in 1705 to get Prussia involved in the war, stating "best Prussia has her own army and makes her own decisions."Feuchtwanger, E. J. Prussia: Myth and Reality: The Role of Prussia in German History. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970. His views, however, were not considered acceptable by his father, and was not until 1713 that Frederick William ascended to the throne. Therefore, in 1715, Prussia, led by Frederick William, joined the coalition for various reasons, including the danger of being attacked from both her rear and the sea; her claims on Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

; and the fact that if she stood aside and Sweden lost, she would not get a share of the territory. Prussia only participated in one battle, the Battle of Stresow

The successful Landing on Groß Stresow by Prussian, Danish and Saxon troops took place on 15 November 1715 on the island of Rügen, Germany during the Great Northern War.

The landing was followed with cavalry assaults from the Swedish defences ...

on the island of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

, as the war had already been practically decided in the 1709 Battle of Poltava

The Battle of Poltava; russian: Полта́вская би́тва; uk, Полта́вська би́тва (8 July 1709) was the decisive and largest battle of the Great Northern War. A Russian army under the command of Tsar Peter I defeate ...

. In the Treaty of Stockholm Prussia gained all of Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

east of the River Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows thr ...

. Sweden would however keep a portion of Pomerania until 1815. The Great Northern War not only marked the end of the Swedish Empire but also elevated Prussia and Russia at the expense of the declining Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as new powers in Europe.

The Great Elector had incorporated the Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

s, the landed aristocracy, into the kingdom's bureaucracy and military machine, giving them a vested interest in the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

and compulsory education

Compulsory education refers to a period of education that is required of all people and is imposed by the government. This education may take place at a registered school or at other places.

Compulsory school attendance or compulsory schooling ...

. King Frederick William I inaugurated the Prussian compulsory conscription system in 1717.

1740–1762: Silesian Wars

In 1740 King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) came to the throne. Using the pretext of a 1537 treaty (vetoed by Emperor Ferdinand I) by which parts of

In 1740 King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) came to the throne. Using the pretext of a 1537 treaty (vetoed by Emperor Ferdinand I) by which parts of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

were to pass to Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

after the extinction of its ruling Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branch ...

, Frederick invaded Silesia, thereby beginning the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

. After rapidly occupying Silesia, Frederick offered to protect Queen Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

if the province were turned over to him. The offer was rejected, but Austria faced several other opponents in a desperate struggle for survival, and Frederick was eventually able to gain formal cession with the Treaty of Berlin in 1742.

To the surprise of many, Austria managed to renew the war successfully. In 1744 Frederick invaded again to forestall reprisals and to claim, this time, the Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, České království),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

. He failed, but French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

pressure on Austria's ally Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

led to a series of treaties and compromises, culminating in the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that restored peace and left Prussia in possession of most of Silesia.

Humiliated by the cession of Silesia, Austria worked to secure an alliance with France and Russia (the "

Humiliated by the cession of Silesia, Austria worked to secure an alliance with France and Russia (the "Diplomatic Revolution

The Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 was the reversal of longstanding alliances in Europe between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War. Austria went from an ally of Britain to an ally of France, the Dutch Republic, a long stan ...

"), while Prussia drifted into Great Britain's camp forming the Anglo-Prussian Alliance. When Frederick preemptively invaded Saxony and Bohemia over the course of a few months in 1756–1757, he began a Third Silesian War

The Third Silesian War () was a war between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia and Archduchy of Austria, Austria (together with its allies) that lasted from 1756 to 1763 and confirmed Prussia's control of the region of Silesia (now in south-western Po ...

and initiated the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

.

This war was a desperate struggle for the Prussian Army, and the fact that it managed to fight much of Europe to a draw bears witness to Frederick's military skills. Facing Austria, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, France, and Sweden simultaneously, and with only Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

(and the non-continental British) as notable allies, Frederick managed to prevent a serious invasion until October 1760, when the Russian army briefly occupied Berlin and Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was named ...

. The situation became progressively grimmer, however, until the death in 1762 of Empress Elizabeth of Russia

Elizabeth Petrovna (russian: Елизаве́та (Елисаве́та) Петро́вна) (), also known as Yelisaveta or Elizaveta, reigned as Empress of Russia from 1741 until her death in 1762. She remains one of the most popular Russian ...

(Miracle of the House of Brandenburg

The Miracle of the House of Brandenburg is the name given by Frederick II of Prussia to the failure of Russia and Austria to follow up their victory over him at the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12 August 1759 during the Seven Years' War. The name is s ...

). The accession of the Prussophile Peter III relieved the pressure on the eastern front. Sweden also exited the war at about the same time.

Defeating the Austrian army at the Battle of Burkersdorf and relying on continuing British success against France in the war's colonial theatres, Prussia was finally able to force a ''status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When used ...

'' on the continent. This result confirmed Prussia's major role within the German states and established the country as a European great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

. Frederick, appalled by the near-defeat of Prussia and the economic devastation of his kingdom, lived out his days as a much more peaceable ruler.

Other additions to Prussia in the 18th century were the County of East Frisia

The County of East-Frisia ( Frisian: Greefskip Eastfryslân; Dutch: Graafschap Oost-Friesland) was a county (though ruled by a prince after 1662) in the region of East Frisia in the northwest of the present-day German state of Lower Saxony.

Coun ...

(1744), the Principality of Bayreuth

The Principality of Bayreuth (german: Fürstentum Bayreuth) or Margraviate of Brandenburg-Bayreuth (''Markgraftum Brandenburg-Bayreuth'') was an immediate territory of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a Franconian branch of the Hohenzollern dyna ...

(1791) and Principality of Ansbach

The Principality or Margraviate of (Brandenburg-)Ansbach (german: Fürstentum Ansbach or ) was a principality in the Holy Roman Empire centered on the Franconian city of Ansbach. The ruling Hohenzollern princes of the land were known as margrave ...

(1791), the latter two being acquired through purchase from branches of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

1772, 1793, and 1795: Partitions of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

To the east and south of Prussia, the

To the east and south of Prussia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

had gradually weakened during the 18th century. Alarmed by increasing Russian influences in Polish affairs and by a possible expansion of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, Frederick was instrumental in initiating the first of the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

between Russia, Prussia, and Austria in 1772 to maintain a balance of power. The Kingdom of Prussia annexed most of the Polish province of Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

, including Warmia

Warmia ( pl, Warmia; Latin: ''Varmia'', ''Warmia''; ; Warmian: ''Warńija''; lt, Varmė; Old Prussian: ''Wārmi'') is both a historical and an ethnographic region in northern Poland, forming part of historical Prussia. Its historic capitals ...

, allowing Frederick to finally adopt the title King ''of'' Prussia; the annexed Royal Prussian land was organised the following year into the Province of West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a Provinces of Prussia, province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kin ...

; most of the rest became the originally separate Netze District

The Netze District or District of the Netze (german: link=no, Netzedistrikt or '; pl, Obwód Nadnotecki) was a territory in the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 until 1807. It included the urban centers of Bydgoszcz (''Bromberg''), Inowrocław (''Ino ...

, which was attached to West Prussia in 1775. The boundary between West Prussia and the territory previously known as the Duchy of Prussia, now the Province of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871 ...

was also adjusted, transferring Marienwerder

Kwidzyn (pronounced ; german: Marienwerder; Latin: ''Quedin''; Old Prussian: ''Kwēdina'') is a town in northern Poland on the Liwa River, with 38,553 inhabitants (2018). It is the capital of Kwidzyn County in the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Geogra ...

to West Prussia (which became its capital) and Warmia (the Heilsberg and districts) to East Prussia. The annexed territory connected East Prussia with the Province of Pomerania, uniting the kingdom's eastern territories.

After Frederick died in 1786, his nephew Fredrick William II continued the partitions, gaining a large part of western Poland in 1793; Thorn

Thorn(s) or The Thorn(s) may refer to:

Botany

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, sharp structures on plants

* ''Crataegus monogyna'', or common hawthorn, a plant species

Comics and literature

* Rose and Thorn, the two personalities of two DC Com ...

(Toruń) and Danzig (Gdańsk), which had remained part of Poland after the first partition, were incorporated into West Prussia, while the remainder became the province of South Prussia

South Prussia (german: Südpreußen; pl, Prusy Południowe) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1793 to 1807.

History

South Prussia was created out of territory annexed in the Second Partition of Poland and in 1793 included:

*the Poz ...

.

In 1787, Prussia invaded Holland to restore the Orangist stadtholderate

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

against the increasingly rebellious Patriots, who sought to overthrow the House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau (Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherlands ...

and establish a democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two exceedingly similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democrac ...

. The direct cause of the invasion was the arrest at Goejanverwellesluis

The Goejanverwellesluis is a lock in Hekendorp, Netherlands. The 'Goejannen' - the men from the surrounding polders who went to sea - said their last farewells by this channel.

According to the tradition, Wilhelmina of Prussia, wife of stadhold ...

, where Frederick William II's sister Wilhelmina of Prussia, also stadtholder William V of Orange

William V (Willem Batavus; 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806) was a prince of Orange and the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. He went into exile to London in 1795. He was furthermore ruler of the Principality of Orange-Nassau until his death in ...

's wife, was stopped by a band of Patriots who denied her passage to The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

to reclaim her husband's position.

In 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist and a large area (including Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

) to the south and east of East Prussia became part of Prussia. Most of the new territories (and the part of South Prussia north of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

) were organised into the province of New East Prussia

New East Prussia (german: Neuostpreußen; pl, Prusy Nowowschodnie; lt, Naujieji Rytprūsiai) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1795 to 1807. It was created out of territory annexed in the Third Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian C ...

; South Prussia gained the area immediately south of the Vistula, Narew

The Narew (; be, Нараў, translit=Naraŭ; or ; Sudovian: ''Naura''; Old German: ''Nare''; uk, Нарва, translit=Narva) is a 499-kilometre (310 mi) river primarily in north-eastern Poland, which is also a tributary of the river Vis ...

and Bug, including Warsaw; a small area to the south of South Prussia became New Silesia

New Silesia (german: Neuschlesien or ''Neu-Schlesien'') was a small Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1795 to 1807, created after the Partitions of Poland, Third Partition of Poland. It was located northwest of Kraków ...

. With the Polish-Lithuanian state gone Prussia now shared its eastern borders with the Habsburg monarchy (West Galicia

New Galicia or West Galicia ( pl, Nowa Galicja or ''Galicja Zachodnia'', german: Neugalizien or ''Westgalizien'') was an administrative region of the Habsburg monarchy, constituted from the territory annexed in the course of the Third Partition ...

) and Russia (Russian partition

The Russian Partition ( pl, zabór rosyjski), sometimes called Russian Poland, constituted the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that were annexed by the Russian Empire in the course of late-18th-century Partitions of Po ...

).

The Partitions were facilitated by the fact that they occurred just before the 19th-century rise of nationalism in Europe, and the national self-awareness was yet to be developed in most European peoples, especially among commoners. The Kingdom of Prussia was perceived in Poland more as a nationality-neutral personal holding of the ruling House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzol ...

, rather than a German nation-state, and any anxiety concerned predominantly freedom to practice religion rather than rights to maintain national identity. The onset of Germanisation in the following decades, later joined by the , quickly changed this benign picture and alienated Poles from the Prussian state, ultimately boosting their national self-awareness and eliciting their national resistance against Prussian rule.

1801–1815: Napoleonic Wars

Following the

Following the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

and the Execution of Louis XVI

The execution of Louis XVI by guillotine, a major event of the French Revolution, took place publicly on 21 January 1793 at the ''Place de la Révolution'' ("Revolution Square", formerly ''Place Louis XV'', and renamed ''Place de la Concorde'' in ...

, Prussia declared war on the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

. When Prussian troops attempted to invade France, they were beaten back and the Treaty of Basel (1795) ended the War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the Kingdom of France (1791-92), constitutional Kingdom of France and then t ...

. In it, the First French Republic and Prussia had stipulated that the latter would ensure the Holy Roman Empire's neutrality in all the latter's territories north of the demarcation line of the River Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

, including the British continental dominions of the Electorate of Hanover and the Duchies of Bremen-Verden. To this end, Hanover (including Bremen-Verden) also had to provide troops for the so-called ''demarcation army'' maintaining this state of ''armed neutrality''.

In the course of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

against France (1799–1802) Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

urged Prussia to occupy Hanover. In 1801, 24,000 Prussian soldiers invaded, surprising Hanover, which surrendered without a fight. In April 1801 the Prussian troops arrived in Bremen-Verden's capital Stade

Stade (), officially the Hanseatic City of Stade (german: Hansestadt Stade, nds, Hansestadt Stood) is a city in Lower Saxony in northern Germany. First mentioned in records in 934, it is the seat of the district () which bears its name. It is l ...

and stayed there until October that year. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Great B ...

first ignored Prussia's hostility, but when it joined the pro-French Second League of Armed Neutrality

The Second League of Armed Neutrality or the League of the North was an alliance of the north European naval powers Denmark–Norway, Prussia, Sweden, and Russia. It existed between 1800 and 1801 during the War of the Second Coalition and was in ...

alongside Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe I ...

and Russia, Britain started to capture Prussian sea vessels. After the Battle of Copenhagen the coalition fell apart and Prussia again withdrew its troops.

At Napoleon's instigation, Prussia recaptured British Hanover and Bremen-Verden in early 1806. On 6 August that year the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved as a result of Napoleon's victories over Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. The title of ''Kurfürst'' (Prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prince ...

) of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

became meaningless, and was dropped. Nonetheless, King Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

was now ''de jure'' as well as ''de facto'' sovereign of all of the Hohenzollern domains. Before this time, the Hohenzollern sovereign had held many titles and crowns, from Supreme Governor of the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Churches (''summus episcopus'') to King, Elector, Grand Duke, Duke for the various regions and realms under his rule. After 1806 he was simply King of Prussia and ''summus episcopus''.

But when Prussia, after it turned against the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

, was defeated in the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt

The twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt (; older spelling: ''Auerstädt'') were fought on 14 October 1806 on the plateau west of the river Saale in today's Germany, between the forces of Napoleon I of France and Frederick William III of Pruss ...

(14 October 1806), Frederick William III was forced to temporarily flee to remote Memel. After the Treaties of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when t ...

in 1807, Prussia lost about half of its territory, including the land gained from the Second and Third Partitions of Poland (which now fell to the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

) and all land west of the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

river. France recaptured Prussian-occupied Hanover, including Bremen-Verden. The remainder of the kingdom was occupied by French troops (at Prussia's expense) and the king was obliged to make an alliance with France and join the Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berlin ...

.

The Prussian reforms

The Prussian Reform Movement was a series of constitutional, administrative, social and economic reforms early in nineteenth-century Prussia. They are sometimes known as the Stein-Hardenberg Reforms, for Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August ...

were a reaction to the Prussian defeat in 1806 and the Treaties of Tilsit. It describes a series of constitutional, administrative, social and economic reforms of the kingdom of Prussia. They are sometimes known as the '' Stein-Hardenberg Reforms'' after Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg (31 May 1750, in Essenrode-Lehre – 26 November 1822, in Genoa) was a Prussian statesman and Prime Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career ...

, their main instigators.

After the defeat of Napoleon in Russia in 1812, Prussia quit the alliance and took part in the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor sixth ...

during the "Wars of Liberation" (''Befreiungskriege'') against the French occupation. Prussian troops under Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt (; 21 December 1742 – 12 September 1819), ''Graf'' (count), later elevated to ''Fürst'' (sovereign prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal). He earned ...

contributed crucially in the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

of 1815 to the final victory over Napoleon.

1815: After Napoleon

Prussia's reward for its part in France's defeat came at the

Prussia's reward for its part in France's defeat came at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

. It regained most of its pre-1806 territory. Notable exceptions included part of the territory annexed in the Second and Third Partitions of Poland, which became Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

under Russian rule (though it did retain Danzig, acquired in the Second Partition). It also did not regain several of its former towns in the south. However, as compensation it picked up some new territory, including 40% of the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Saxon ...

and much of Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

and the Rhineland. Prussia now stretched uninterrupted from the Niemen in the east to the Elbe in the west, and possessed a chain of disconnected territories west of the Elbe. This left Prussia as the only great power with a predominantly German-speaking population.

With these gains in territory, the kingdom was reorganized into 10 provinces. Most of the kingdom, aside from the provinces of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

, and the autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (german: Großherzogtum Posen; pl, Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the ...

but including the formerly Polish Lauenburg and Bütow Land

Lauenburg and Bütow Land (german: Länder or , csb, Lãbòrskò-bëtowskô Zemia, pl, Ziemia lęborsko-bytowska) formed a historical region in the western part of Pomerelia (Polish and papal historiography) or in the eastern part of Farther Pom ...

and the Draheim territory, became part of the new German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, a confederacy of 39 sovereign states (including Austria and Bohemia) replacing the defunct Holy Roman Empire.

Frederick William III submitted Prussia to a number of administrative reforms, among others reorganising the government by way of ministries, which remained formative for the following hundred years.

As to religion, reformed Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

Frederick William III—as ''Supreme Governor of the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Churches''—asserted his long-cherished project (started in 1798) to unite the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

and the Reformed Church

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

in 1817, (see Prussian Union). The Calvinist minority, strongly supported by its co-religionist Frederick William III, and the partially reluctant Lutheran majority formed the united

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

Protestant Evangelical Church in Prussia

The Prussian Union of Churches (known under multiple other names) was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Pru ...

. However, ensuing quarrels causing a permanent schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

among the Lutherans into united and Old Lutherans

Old Lutherans were originally German Lutherans in the Kingdom of Prussia, notably in the Province of Silesia, who refused to join the Prussian Union of churches in the 1830s and 1840s. Prussia's king Frederick William III was determined to unif ...

by 1830.

As a consequence of the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, the Principalities of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

( en, Nothing without God)

, national_anthem =

, common_languages = German

, religion = Roman Catholic

, currency =

, title_leader = Prince

, leader1 ...

and Hohenzollern-Hechingen

Hohenzollern-Hechingen was a small principality in southwestern Germany. Its rulers belonged to the Swabian branch of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

History

The County of Hohenzollern-Hechingen was created in 1576, upon the partition of the Coun ...

(ruled by a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern) were annexed by Prussia in 1850, later united as the Province of Hohenzollern

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

.

1848–1871: German wars of unification

During the half-century that followed the Congress of Vienna a conflict of ideals took place within the German Confederation between the formation of a single German nation and the conservation of the current collection of smaller German states and kingdoms. The main debate centered around whether Prussia or theAustrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

should be the leading member of any unified Germany. Those advocating for Prussian leadership contended that Austria had far too many non-German interests to work for the greater good of Germany. They argued that Prussia, as by far the most powerful state with a majority of German-speakers, was best suited to lead the new nation.

The establishment of the German Customs Union (Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

) in 1834, which excluded Austria, increased Prussian influence over the member states. In the wake of the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

in 1849 offered King Frederick William IV of Prussia

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

the crown of a united Germany. Frederick William refused the offer on the grounds that revolutionary assemblies could not grant royal titles. But he also refused for two other reasons: to do so would have done little to end the internal power-struggle between Austria and Prussia, and all Prussian kings (up to and including William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

) feared that the formation of a German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

would mean the end of Prussia's independence within the German states.

In 1848 actions taken by Denmark towards the Duchies of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

and Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

led to the First War of Schleswig

The First Schleswig War (german: Schleswig-Holsteinischer Krieg) was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question, contesting the issue of who should control the Duchies of Schleswig, ...

(1848–51) between Denmark and the German Confederation, resulting in a Danish victory.

Frederick William issued Prussia's first constitution by his own authority in 1848, modifying it in the Constitution of 1850. These documents—moderate by the standards of the time but conservative by today's—provided for a two-chamber parliament, the ''Landtag''. The lower house, later known as the , was elected by all males over the age of 25 using the Prussian three-class franchise

The Prussian three-class franchise (German: ''Preußisches Dreiklassenwahlrecht'') was an indirect electoral system used from 1848 until 1918 in the Kingdom of Prussia and for shorter periods in other German states. Voters were grouped by distric ...

. Voters were divided into three classes whose votes were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid. In one typical election, the first class (with those who paid the most in taxes) included 4% of voters and the third class (with those who paid the least) had 82%, yet each group chose the same number of electors. The system all but assured dominance by the more well-to-do men of the population. The upper house, later renamed the ''Herrenhaus'' ("House of Lords"), was appointed by the king. He retained full executive authority, and ministers were responsible only to him. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

s, remained unbroken, especially in the eastern provinces. The constitution nevertheless contained a number of liberal elements such as the introduction of jury courts and a catalog of fundamental rights that included freedom of religion, speech and the press.

Frederick William suffered a stroke in 1857, and his younger brother, Prince William, became regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

. William pursued a considerably more moderate policy. Upon Frederick William IV's death in 1861 he succeeded to the Prussian throne as William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

. However, shortly after becoming king, he faced a dispute with his parliament over the size of the army. The parliament, dominated by the liberals, balked at William's desire to increase the number of regiments and withheld approval of the budget to pay for its cost. A deadlock ensued, and William seriously considered abdicating in favour of his son, Crown Prince Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

. Ultimately, he decided to appoint as prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, at that time the Prussian ambassador to France. Bismarck took office on September 23, 1862.