Royal Dixon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Royal Dixon (25 March 1885 – 4 June 1962) was an American

Dixon's philosophical world-view was essentially panpsychic. From his studies in botany and natural science he held the view that everything was alive and that even

Dixon's philosophical world-view was essentially panpsychic. From his studies in botany and natural science he held the view that everything was alive and that even

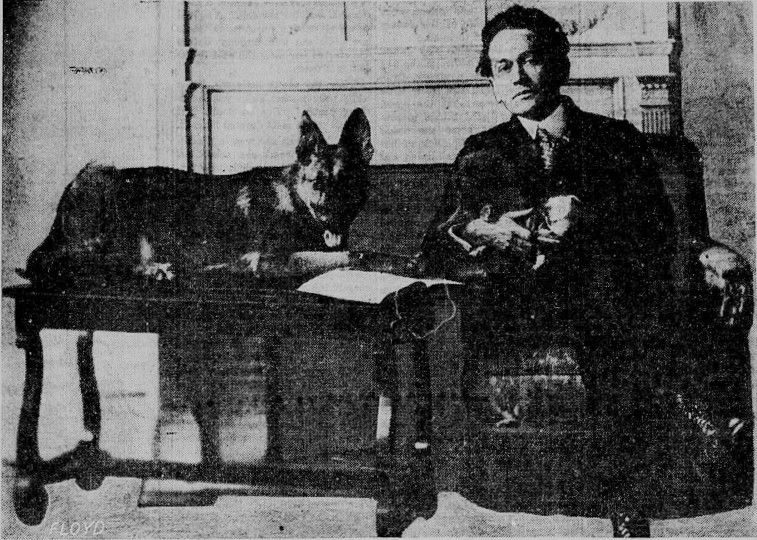

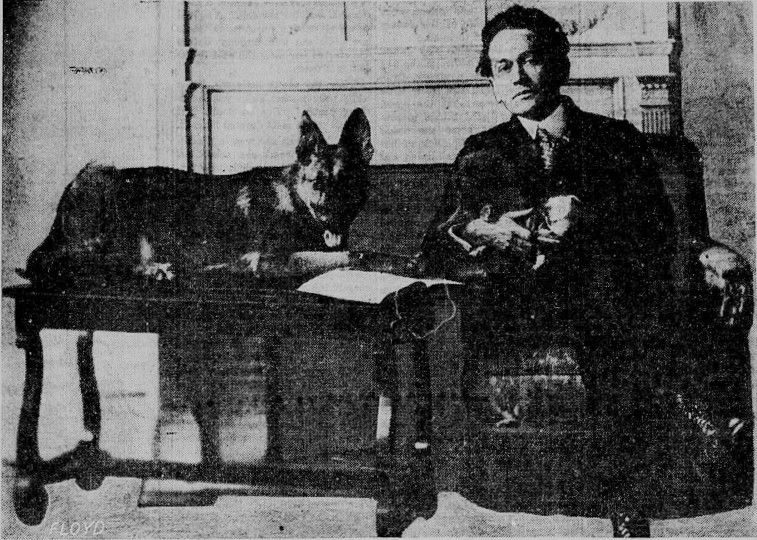

Royal Dixon and Chester Snowden

by Brandon Wolf.

''The Human Side of Plants'' (1914)

''Signs is Signs''

(1915)

''Americanization''

(1916)

''Forest Friends''

(1916)

''The Human Side of Trees: Wonders of the World''

(with Franklyn Everett Fitch, 1917)

''The Human Side of Birds''

(1917)

''The Human Side of Animals''

(1918) * ''Hidden Children'' (1922)

''Personality of Plants''

(with Franklyn Everett Fitch, 1923)

''Personality of Insects''

(with Brayton Eddy, 1924) * ''The Personality of Water-Animals'' (with Brayton Eddy, 1925) * ''The Ape of Heaven'' (1936) * ''Half Dark Moon'' (1939)

Royal Dixon Papers Now Available (2016)

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Royal 1885 births 1962 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American botanists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American philosophers American animal rights activists American animal rights scholars American male non-fiction writers American nature writers American political writers Animal cognition writers Anti-vivisectionists Burials at Glenwood Cemetery (Houston, Texas) American gay writers Panpsychism People associated with the Field Museum of Natural History People from Huntsville, Texas

animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

activist, botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

, philosopher, and a member of the Americanization

Americanization or Americanisation (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences) is the influence of American culture and business on other countries outside the America, United ...

movement. He was, along with Diana Belais (1858–1944), a founder of the "First Church for Animal Rights" in 1921.

Biography

Dixon was born atHuntsville, Texas

Huntsville is a city in and the county seat of Walker County, Texas. The population was 45,941 as of the 2020 census. It is the center of the Huntsville micropolitan area. Huntsville is in the East Texas Piney Woods on Interstate 45 and home to ...

on 25 March 1885 to Elijah and Francis Elizabeth Dixon. He was educated at the Sam Houston Normal Institute

Sam Houston State University (SHSU or Sam) is a public university in Huntsville, Texas. It was founded in 1879 and is the third-oldest public college or university in Texas. It is one of the first normal schools west of the Mississippi River and ...

, Morgan Park Academy, Chicago and later as a special student at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

. His earliest career was as a child actor and dancer trained by Adele Fox. His last theatre appearance was in 1903 as an actor with the Iroquois theater in Chicago. He became a curator at the department of botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

at the Field Museum of Chicago from 1905 to 1910. He subsequently became a staff writer at the ''Houston Chronicle

The ''Houston Chronicle'' is the largest daily newspaper in Houston, Texas, United States. , it is the third-largest newspaper by Sunday circulation in the United States, behind only ''The New York Times'' and the ''Los Angeles Times''. With it ...

''. He also made special contributions to the newspapers of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where he lectured for the Board of Education

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional are ...

and founded a school for creative writing. His interest and attention were later directed to immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

, as a director of publicity of the Commission of Immigrants in America, and as managing editor of '' The Immigrants in America Review''. He published a book on how immigrants needed to be "americanized" into a single uniform culture.

Philosophy

Dixon's philosophical world-view was essentially panpsychic. From his studies in botany and natural science he held the view that everything was alive and that even

Dixon's philosophical world-view was essentially panpsychic. From his studies in botany and natural science he held the view that everything was alive and that even insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s and plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s have personality. For example, in his book ''The Human Side of Plants'' he argued that plants are sentient and have minds and souls. A review in the ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' journal described the book as "partly a rebound from a ''hortus siccus'' botany, partly an uncritical vitalism, and partly a somewhat saddening illustration of the lack of critical balance." The review was disappointed by this because Dixon cited many interesting facts about plants including their adaptations and movements but was criticized for anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology.

Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics t ...

when comparing plant activities to humans.

Dixon was a Christian who believed that the scriptures imply that "man and beasts" equally share a future life beyond physical death. In his book ''The Personality of Water-Animals'' he wrote that "the Greatest of all teachers Christ knew the value of marine education for he chose as his disciples men thoroughly acquainted with the sea".

The First Church of Animal Rights

In 1921, Dixon founded, along with Diana Belais, Dr. S.A. Schneidmann and several others, the First Church for Animal Rights in Manhattan and it had a membership of about 300 people. The inauguration of the church was held on 13 March 1921 at the Hotel Astor. Nearly 400 people attended the inauguration and the speakers included Mrs Edwin Markham, Dr John Edward Oster, Mrs Margaret Crumpacker, Miss Jessie B. Rittenhouse, Dr. A.L. Lucas and Miles M. Dawson. A full list of the church's objectives included: * To preach and teach the oneness of all life, and awaken the humane consciousness * To champion the cause of animals' rights * To develop the character of youth through humane education * To train and send forth humane workers * To awaken the realization that every living creature has the inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness * To act as a spiritual fountain-head and spokesman of human organizations and animal societies, and give a better understanding of their work and needs to the public. Dixon is cited as an early activist and philosopher of animal rights. HistorianRoderick Nash

Roderick Frazier Nash is a professor emeritus of history and environmental studies at the University of California Santa Barbara. He was the first person to descend the Tuolumne River using a raft.

Scholarly biography

Nash received his Bache ...

has commented that "Dixon tried to call Americans' attention to the idea that all animals have "the inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness".

Personal life

Dixon lived with his partner, a local artist, Chester Snowden. Dixon's letters and works are archived at the University of Houston Library. Dixon was buried in Houston's Glenwood Cemetery.by Brandon Wolf.

Selected publications

''The Human Side of Plants'' (1914)

''Signs is Signs''

(1915)

''Americanization''

(1916)

''Forest Friends''

(1916)

''The Human Side of Trees: Wonders of the World''

(with Franklyn Everett Fitch, 1917)

''The Human Side of Birds''

(1917)

''The Human Side of Animals''

(1918) * ''Hidden Children'' (1922)

''Personality of Plants''

(with Franklyn Everett Fitch, 1923)

''Personality of Insects''

(with Brayton Eddy, 1924) * ''The Personality of Water-Animals'' (with Brayton Eddy, 1925) * ''The Ape of Heaven'' (1936) * ''Half Dark Moon'' (1939)

References

External links

Royal Dixon Papers Now Available (2016)

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Royal 1885 births 1962 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American botanists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American philosophers American animal rights activists American animal rights scholars American male non-fiction writers American nature writers American political writers Animal cognition writers Anti-vivisectionists Burials at Glenwood Cemetery (Houston, Texas) American gay writers Panpsychism People associated with the Field Museum of Natural History People from Huntsville, Texas