Rossa Matilda Richter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rossa Matilda Richter (7 April 1860–8 December 1937), who used the stage name Zazel, was an English

Rossa Matilda Richter (7 April 1860–8 December 1937), who used the stage name Zazel, was an English

Most sources, including the ''

Most sources, including the ''

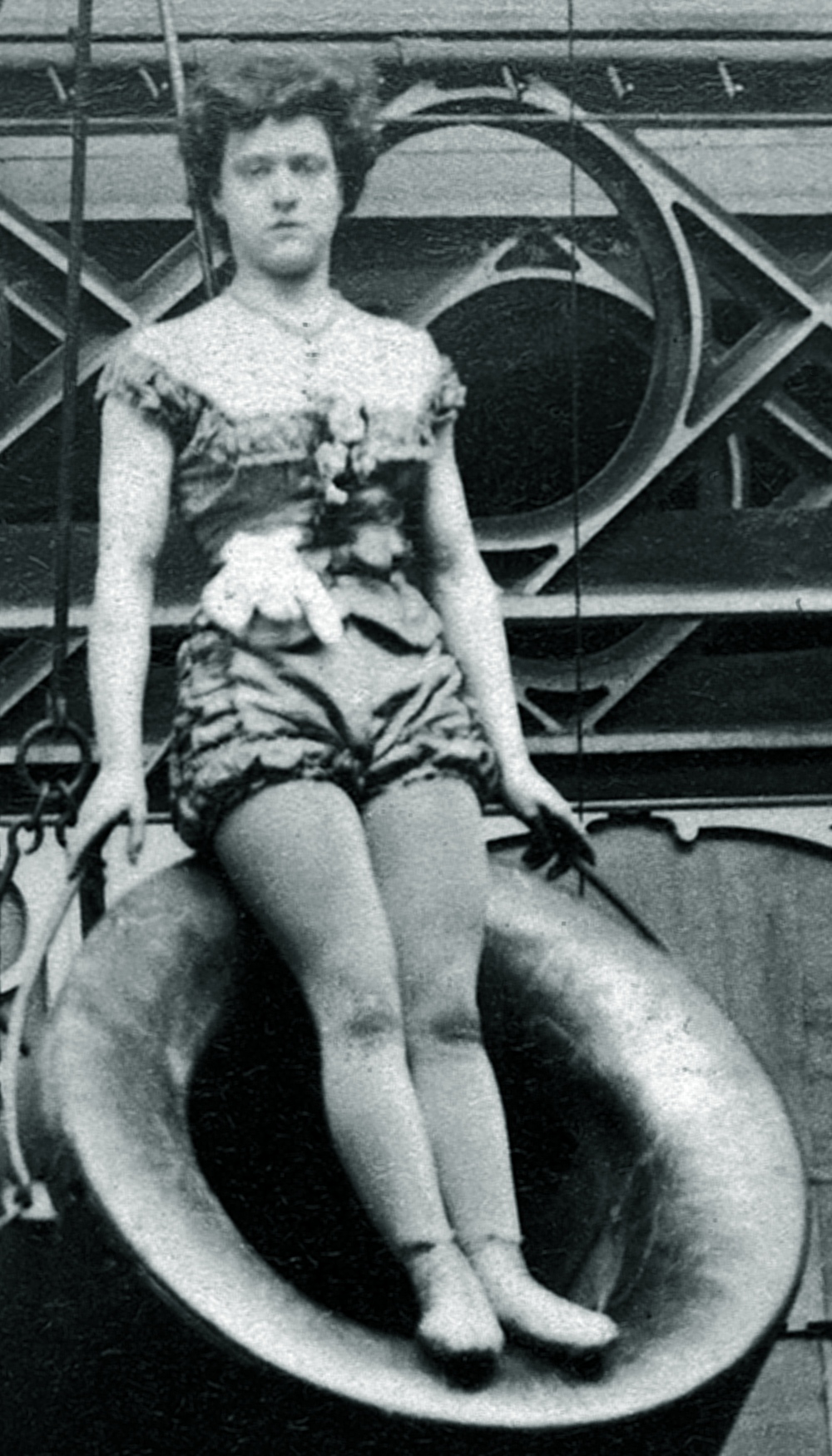

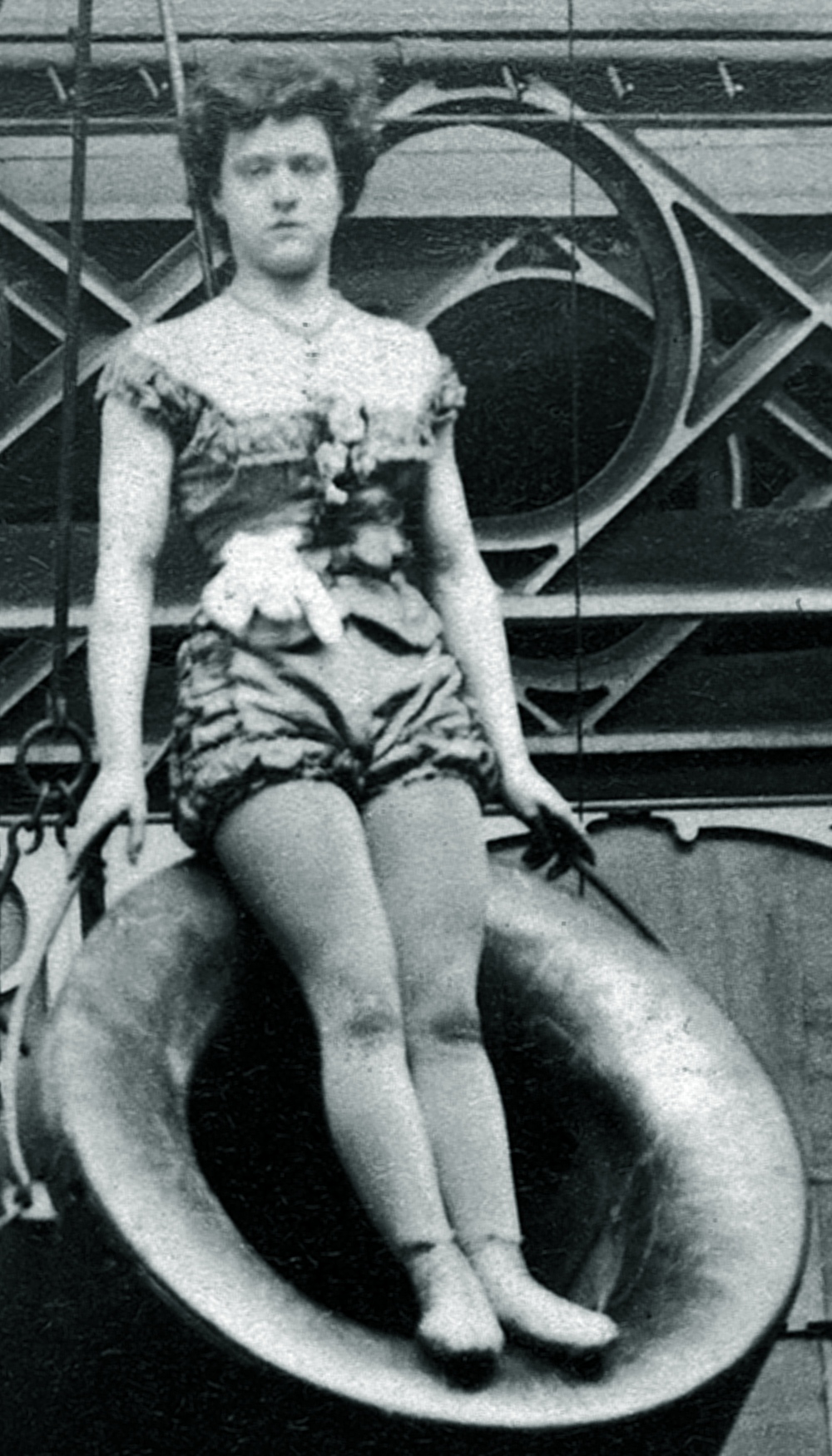

Press coverage of Richter's performances remarked on the impressive spectacle of the act and her fearlessness and athleticism. ''The West Australian'' wrote that "there was never a more fearless woman gymnast" and said that "fear was to her an unknown quantity". That she also jumped out of buildings to demonstrate the functionality of a safety net further established that she was brave even outside of the confines of a circus tent. The ''Clipper'' said that "personally Zazel is bright, intelligent and noted for her acts of charity."

Though young, Richter was sexualised in advertising materials from the time of her earliest Zazel performances. Whereas ''The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News'' explained that women may appreciate her athleticism, it also provided several descriptions of her "most perfect" figure. Brian Tyson speculated that, looking at the advertising materials, some of the act's appeal may have been because "in order to fit into the cannon, she had to shed most of her Victorian clothing." The painter

Press coverage of Richter's performances remarked on the impressive spectacle of the act and her fearlessness and athleticism. ''The West Australian'' wrote that "there was never a more fearless woman gymnast" and said that "fear was to her an unknown quantity". That she also jumped out of buildings to demonstrate the functionality of a safety net further established that she was brave even outside of the confines of a circus tent. The ''Clipper'' said that "personally Zazel is bright, intelligent and noted for her acts of charity."

Though young, Richter was sexualised in advertising materials from the time of her earliest Zazel performances. Whereas ''The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News'' explained that women may appreciate her athleticism, it also provided several descriptions of her "most perfect" figure. Brian Tyson speculated that, looking at the advertising materials, some of the act's appeal may have been because "in order to fit into the cannon, she had to shed most of her Victorian clothing." The painter

Rossa Matilda Richter (7 April 1860–8 December 1937), who used the stage name Zazel, was an English

Rossa Matilda Richter (7 April 1860–8 December 1937), who used the stage name Zazel, was an English aerialist

Acrobatics () is the performance of human feats of balance, agility, and motor coordination. Acrobatic skills are used in performing arts, sporting events, and martial arts. Extensive use of acrobatic skills are most often performed in acro d ...

and actor

An actor or actress is a person who portrays a character in a performance. The actor performs "in the flesh" in the traditional medium of the theatre or in modern media such as film, radio, and television. The analogous Greek term is (), li ...

who became known as the first human cannonball

The human cannonball act is a performance in which a person who acts as the "cannonball" is ejected from a specially designed cannon. The human cannonball lands on a horizontal net or inflated bag placed at the landing point, as predicted by phys ...

at the age of 17. She began performing at a very young age, practicing aerial stunts like tightrope walking

Tightrope walking, also called funambulism, is the skill of walking along a thin wire or rope. It has a long tradition in various countries and is commonly associated with the circus. Other skills similar to tightrope walking include slack rope ...

in an old London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

church. She took up ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

, gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shou ...

, and trapeze

A trapeze is a short horizontal bar hung by ropes or metal straps from a ceiling support. It is an aerial apparatus commonly found in circus performances. Trapeze acts may be static, spinning (rigged from a single point), swinging or flying, an ...

by the time she was 6 and, at 12, went on tour with a travelling acrobat

Acrobatics () is the performance of human feats of balance, agility, and motor coordination. Acrobatic skills are used in performing arts, sporting events, and martial arts. Extensive use of acrobatic skills are most often performed in acro ...

troupe. In 1877, she was the first person to be fired out of a cannon, in front of a large crowd at the Royal Aquarium

The Royal Aquarium and Winter Garden was a place of amusement in Westminster, London. It opened in 1876, and the building was demolished in 1903. The attraction was located northwest of Westminster Abbey on Tothill Street. The building was design ...

.

Journalists and the public voiced concerns for her safety from the time of her earliest appearances as Zazel. She was named by a lawmaker as one of the reasons for proposed legislation in England to prevent dangerous acrobatic stunts, leading her to take the show to the United States. She toured Europe and North America with circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclist ...

es including Barnum & Bailey, executing tightrope, trapeze, and high dive routines in addition to the human cannonball. Throughout her career, she suffered several accidents and injuries, the most serious of which largely ended her career in 1891.

During time off from the circus, she started an opera company with her husband and took singing roles in some of its productions. She also volunteered time writing and holding exhibitions to promote the life-saving potential for safety net

A safety net is a net to protect people from injury after falling from heights by limiting the distance they fall, and deflecting to dissipate the impact energy. The term also refers to devices for arresting falling or flying objects for the ...

s.

Early life

Richter was born inLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1860 to a father from Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

and a mother from Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

. Her father, Ernst Karl Richter, was a well known talent agent

A talent agent, or booking agent, is a person who finds jobs for actors, authors, broadcast journalists, film directors, musicians, models, professional athletes, screenwriters, writers, and other professionals in various entertainment or sport ...

who supplied performers and animals to circuses and other productions. Her mother, Susanne Richter, was a dancer in a circus. She was the second of at least four children. As a child, she was taught how to fall before she was taught how to perform, practising in an old condemned church in London, where her wire stretched from the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

down through the nave to the gallery, and her nets spread below.

She began her performance career at the age of four or five, playing one of Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

's sisters in a pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking ...

at the Raglan Music Hall. She was only filling in for another child who had fallen ill, but according to the ''New York Clipper

The ''New York Clipper'', also known as ''The Clipper'', was a weekly entertainment newspaper published in New York City from 1853 to 1924. It covered many topics, including circuses, dance, music, the outdoors, sports, and theatre. It had a ...

'', "she filled the role so well that she became a favorite" and gave a series of additional performances at the Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster.

Notable landmarks ...

theatre. She received ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

lessons from a respected instructor and subsequently took up gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shou ...

, learning from teachers named Stergenbach and the Levanti brothers. She also became active as a trapeze

A trapeze is a short horizontal bar hung by ropes or metal straps from a ceiling support. It is an aerial apparatus commonly found in circus performances. Trapeze acts may be static, spinning (rigged from a single point), swinging or flying, an ...

artist from the time she was six years old, performing for the first time at Garrick Theatre

The Garrick Theatre is a West End theatre, located in Charing Cross Road, in the City of Westminster, named after the stage actor David Garrick. It opened in 1889 with ''The Profligate'', a play by Arthur Wing Pinero, and another Pinero play ...

in Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

. She became known for a "leap-for-life" stunt on the trapeze which she performed throughout her career. During some of these early performances, she used the stage name La Petite Lulu.

When she was twelve, she joined a travelling Japanese or Siamese acrobat

Acrobatics () is the performance of human feats of balance, agility, and motor coordination. Acrobatic skills are used in performing arts, sporting events, and martial arts. Extensive use of acrobatic skills are most often performed in acro ...

troupe, with whom she honed her balancing skills that she would rely upon throughout her circus career. They travelled to put on shows in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, and Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

. Although she was English, a contemporary article in the ''Clipper'' said "she was known as the only Japanese girl that ever visited Europe, and received many medals as rewards for her daring and skill." During the show in Toulouse, she suffered the first of many accidents during a performance, falling during a trapeze act. Her injury was severe enough that it took her away from performing for a short time. According to her father, it was because he would not sanction further performances. Richter returned home to London in 1873.

Human cannonball at the Royal Aquarium

Thehuman cannonball

The human cannonball act is a performance in which a person who acts as the "cannonball" is ejected from a specially designed cannon. The human cannonball lands on a horizontal net or inflated bag placed at the landing point, as predicted by phys ...

act was conceived by William Leonard Hunt

William Leonard Hunt (June 10, 1838 – January 17, 1929), also known by the stage name The Great Farini, was a well-known nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Canadian funambulist, entertainment promoter and inventor, as well as the first kn ...

, a Canadian daredevil who went by the name "The Great Farini." He was known both for his own high wire

Tightrope walking, also called funambulism, is the skill of walking along a thin wire or rope. It has a long tradition in various countries and is commonly associated with the circus. Other skills similar to tightrope walking include slack rope ...

performances, such as when he crossed Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

, and for the high-profile performers he managed. Before Richter, Farini's best known act was his adopted son Samuel Wasgate. Starting in 1870, Farini dressed him in women's clothing and began advertising performances for "The Beautiful Lulu the girl Aerialist and Circassian Catapultist." The Lulu act was very successful and became known for stunts which involved Wasgate being launched by catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored p ...

, either into a net or up to a trapeze. It was not until a serious accident sent him to the hospital that his true identity became known. Lulu's catapult act led Farini to conceive of a cannon-based act. In 1871, years before its first public display, he filed a patent in the US for "certain new and useful Apparatus for Projecting Persons and Articles into or through the Air." When the Royal Aquarium

The Royal Aquarium and Winter Garden was a place of amusement in Westminster, London. It opened in 1876, and the building was demolished in 1903. The attraction was located northwest of Westminster Abbey on Tothill Street. The building was design ...

in London hired him to improve its profitability, he did so through spectacular acts like the human cannonball.

Ernst Richter was familiar with Farini and, years prior, had sworn that he "should never have a dog of mine, much less a daughter, for his dangerous performances." He added, "What, indeed, would the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

A Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) is a common name for non-profit animal welfare organizations around the world. The oldest SPCA organization is the RSPCA, which was founded in England in 1824. SPCA organizations operate i ...

say to Farini firing off even a donkey from a cannon?" Suzanne Richter was not so protective, however, and Ernst said she misled him into signing an agreement that he believed would be with one of his friends, not Farini, and would only have Rossa singing and dancing.

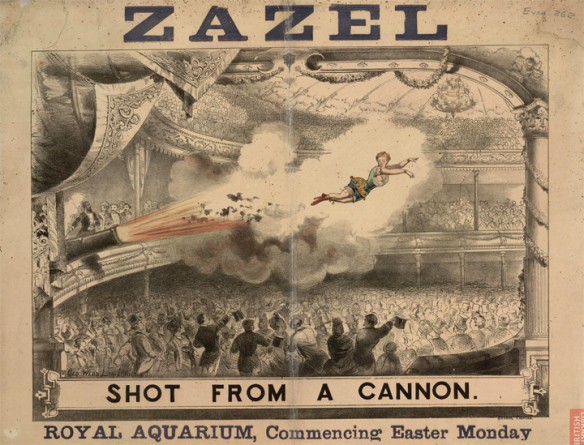

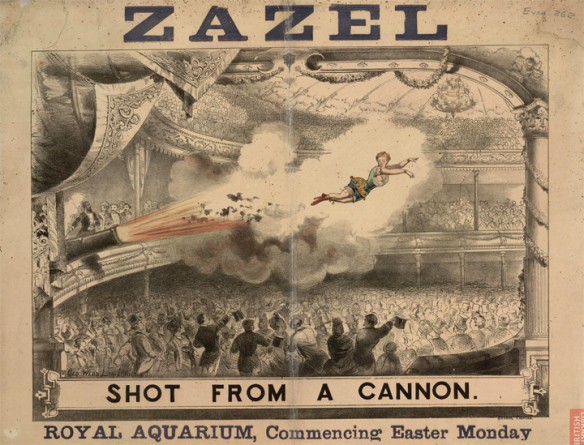

In April 1877, the 17-year-old Richter became known in Europe as the first human cannonball, performing as "Zazel, the Beautiful Human Cannonball," although Hunt's son "Lulu" had been performing the human cannonball act since 1873. The ''Mackay Mercury'' wrote that the event "hurled her from the jaws of death into the arms of fame." She was fired out of a spring-style cannon, before travelling through the air and landing in a net. Accounts of the event vary on the distance she traveled, citing between and . The cannon used rubber springs to limit the distance she would travel. Although Farini had filed another patent in England in 1875 (and in the US in 1879) for an "adaptation f the cannonso as to use explosives as a means for releasing the catch," he was already using a gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

-based explosion for effect during the show.

Most sources, including the ''

Most sources, including the ''Guinness Book of World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a reference book published annually, listing world ...

'', cite Richter as the first human cannonball. However, the claim has been contested by others who claim that "The Australian Marvels," Ella Zuila and George Loyal, performed the act a few years earlier. Zuila and Loyal were hired by Adam Forepaugh

Adam John Forepaugh (born Adam John Forbach; February 28, 1831 – January 22, 1890) was an American horse trader and circus owner. From 1865 through 1890 his circus operated under various names including Forepaugh's Circus, Forepaugh's Gigantic ...

, an American circus owner who learned that his rival, Barnum, may bring Richter to North America. The duo were a featured attraction in Forepaugh's circus and drew comparisons to Richter for their similar aerial stunts. Their cannonball stunts differed somewhat in that rather than being fired from a cannon into a net, Loyal was projected from the cannon and caught by Zuila, who would be hanging upside down with her knees over the bar of a trapeze.

Richter was featured at the Aquarium for an extended period of time, performing sometimes twice in a day, and often to a full room of people. A single performance could draw tens of thousands of people. Farini also brought her to perform at other venues in western Europe. Louis Cooke wrote in ''The Billboard'' that "the breathless silence that always preceded the act while it was being prepared only added to its intensity, and the graceful bow of the young lady who had the temerity and muscular strength to withstand the shock and presence of mind to guide her flight never failed to receive a round of rapturous applause." After seeing it multiple times, a writer for ''The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News'' wrote a gushing review of the act in the 26 May 1877 issue. It praised "her unhesitating confidence, the graceful ease and swiftness of her motions, together with her placidly smiling face, hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

destroy all sense of fear for her safety in the minds of the audience, and enable them to enjoy the spectacle of her extraordinary agility, strength, and seemingly terribly daring feats, with none but pleasurable, although strongly excited sensations." The author went on to describe the mix of anxiety and delight an audience member should expect to experience, and noted that Richter counted among her fans future king Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

, who reportedly attended two of her shows when he was Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

.

Music often accompanied her performances. At the Aquarium, musical director Charles Dubois composed waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

es for her, which featured prominently in some of the show's advertising. Farini also wrote a song, "Zazel," which was sung by George Leybourne

George Leybourne (17 March 1842 – 15 September 1884) was a ''Lion comique'' of the British Victorian music hall who, for much of his career, was known by the title of one of his songs, " Champagne Charlie". Another of his songs, and one that ...

and published by Musical Bouquet.

The human cannonball was not her only act. She began performing a high dive at around the same time, also at the Aquarium. For that stunt, she would make repeated jumps from a raised platform into a net, gradually increasing the distance until she reached a peak of . The ''West Australian'' wrote that she would start atop the proscenium arch

A proscenium ( grc-gre, προσκήνιον, ) is the metaphorical vertical plane of space in a theatre, usually surrounded on the top and sides by a physical proscenium arch (whether or not truly "arched") and on the bottom by the stage floor ...

, fall into the net, then pop up to smile at the audience. She also walked the tightrope

Tightrope walking, also called funambulism, is the skill of walking along a thin wire or rope. It has a long tradition in various countries and is commonly associated with the circus. Other skills similar to tightrope walking include slack rope ...

, increasing the difficulty by sometimes forgoing the standard balancing pole. She would also include tricks such as running, standing on one foot, putting baskets on her feet, lying down or sitting on the wire, and spinning around while holding it with her knees. ''The Era'' wrote that the dive was "astounding" and that "she is wonderfully clever and graceful" on the tightrope.

Accidents and public response

Once the human cannonball act started and became popular, people began protesting the perceived danger of the show and tried unsuccessfully to have it stopped. Concerned complaints made their way to theHome Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, Richard Assheton Cross, who told the Aquarium's manager, Wybrow Robertson, that he would be accountable should an accident befall Richter. In response, Robertson invited Cross to be fired out of the cannon himself.

Richter's first human cannonball accident was at the Aquarium, followed by another in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

in 1879, where the net used to catch her was rotten due to wear and she fell through. Though she did not break any bones, her condition was serious enough that she could not perform the next day. ''The Citizen'' wrote about the outrage expressed at the apparently sloppy safety checks that had missed the poor condition of the net: "If the public demands such sickening exhibitions ... then most certainly it is the bounden duty of those in authority to see that the precaution is a reality, and not a farce." ''The Graphic

''The Graphic'' was a British weekly illustrated newspaper, first published on 4 December 1869 by William Luson Thomas's company Illustrated Newspapers Ltd. Thomas's brother Lewis Samuel Thomas was a co-founder. The premature death of the latt ...

'' insisted, "When will the Home Secretary be made to see the necessity of putting some restraint upon the suicidal sensational acrobatic feats, which are now, to our shame, be it said, so popular?" An 1880 issue of ''The Orchestra'' likewise scolded audiences, saying that these acts "prove the morbid taste of the public who delight in such exhibitions."

After the Portsmouth accident, Ernst Richter went to the office of the periodical ''Truth

Truth is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth 2005 In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs ...

'' to talk to one of its writers. It had published the opinion that someone ought to prevent her from performing such a dangerous act, and Ernst came to ask them how he could do just that. He was afraid for her safety and wanted to get her away from Farini and his stunts. By that time, Ernst had left the entertainment business, worked as an engineer, and had separated from Susanna, with whom Rossa lived and who raised no such objections to the potential for danger. Ernst said that "the newspapers say that someone ought to interfere to hinder her from risking her life for money. I am her father, and want to interfere ... When the cannon is fired off, her limbs have to be rigid. If by mistake it is fired one moment too soon, she might be killed. When she takes her dive, if she did not fall lightly, she would break a limb; and if the net underneath is rotten, as it was at Portsmouth, she might be killed." The ''Truth'' reporter admitted he did not know much about the law, but said he should talk to a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

to ask how to get an injunction

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in pa ...

, opining that the justice system should indeed "prevent girls and children from risking their limbs in order that, with or without the consent of their parents, their task-masters may deserve profit."

Later the same year, on 15 December 1879, she fell during a trapeze performance in Chatham, Kent

Chatham ( ) is a town located within the Medway unitary authority in the ceremonial county of Kent, England. The town forms a conurbation with neighbouring towns Gillingham, Rochester, Strood and Rainham.

The town developed around Chatham ...

. The ''New York Clipper'' reported that the net seemed not to be much protection in the spot she landed, and she "was in an apparently senseless condition", exclaiming "I am killed, I am killed!" as she was taken away from the performing area. She was not found to be seriously injured and later performed again with her hands bandaged, "and evidently suffering from great nervousness."

In 1880 Edward Jenkins brought the Acrobats and Gymnasts' Bill to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, which aimed to prevent dangerous acrobatic stunts. There was some push-back to the idea based on the notion that it might also prohibit less dangerous acrobatic performances, to which Jenkins clarified that it really had a handful of performers in mind, including Zazel. There was extended debate across two parliaments, much of it focused on how to draw the line between dangerous and acceptable acts. Many years later, Richter gave her opinion of the legal interventions in an interview with John Squire, eventually published in ''Solo & Duet'': "A lot of those interfering men in Parliament started a committee about it and they passed a law forbidding me to do it. Oh, I was wretched! ... I loved it. They'd just no right to take away me living if I loved it. I was ambitious. I wanted to be great. You see, it was me art."

Touring with Barnum & Bailey and other circuses

The relationship between Richter and Farini was nearer to manager-employee than collaborators, and Farini kept most of the earnings from the lucrative shows, amounting to 120–200pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO 4217, ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of #Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories, its associated territori ...

per week. In 1879, a reporter observed that when travelling to different venues, she did so with a normal train ticket: "it might have been supposed that those who derive rich benefits from the clever but dangerous performances ... would have paid for her the very small difference between a first- and second-class ticket from Sloane Square

Sloane Square is a small hard-landscaped square on the boundaries of the central London districts of Belgravia and Chelsea, located southwest of Charing Cross, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The area forms a boundary betwe ...

to St. James's Park

St James's Park is a park in the City of Westminster, central London. It is at the southernmost tip of the St James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St James the Less. It is the most easterly of a near-continuous ch ...

." According to P. T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum (; July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman, businessman, and politician, remembered for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding the Barnum & Bailey Circus (1871–2017) with James Anthony Bailey. He was ...

, who had travelled to London to see the performance, Richter pleaded with him to take her away. She was upset at the small share of money she received from Farini, when she was the star of the act and took the physical risks.

Farini made it well known that the Zazel act belonged to him, publicizing notices to that effect. When Richter began asking for more money, he secretly began training additional young women to perform as Zazel. It is unclear when and to what extent the other "Zazels" performed, but the number of acts using that name became common enough that Richter began to refer to herself as "the original Zazel."

In 1880, during proceedings concerning the Acrobats and Gymnasts' Bill, Farini and Richter left England. She performed with the Barnum & Bailey Circus

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus (also known as the Ringling Bros. Circus, Ringling Bros., the Barnum & Bailey Circus, Barnum & Bailey, or simply Ringling) is an American traveling circus company billed as The Greatest Show on Ear ...

for a season, performing in France and then the United States. Her 8 April 1880 debut in New York "was in every way successful, and received fervid applause," according to the ''Clipper''. Though she was best known as a human cannonball, Richter continued to perform other aerial acts, like the high dive and trapeze. She returned to Europe with Farini in November 1881, stayed a short time, and returned to the United States in 1882, touring with John B. Doris's Inter-Ocean Show.

Opera

Richter married George Oscar Starr, who worked as a press agent for Barnum; and, together, they took some time away from the circus. Among other activities, they launched the Starr Opera Company in 1886. They intended it to be accessible to a popular audience, and even staged a concert for people incarcerated at Michigan State Prison. Though she was not previously known for singing, it had been reported that she sang a song called "It Is So Easy" after certain circus performances. She played various parts in comic opera, including a performances as Regina in ''La princesse de Trébizonde

''La Princesse de Trébizonde'' is an opéra bouffe with music by Jacques Offenbach and text by Étienne Tréfeu and Charles-Louis-Étienne Nuitter. The work was first given in two acts at the Theater Baden-Baden on 31 July 1869 and subsequently ...

'' and Eliza in '' Billee Taylor, or The Reward of Virtue''. According to the ''Clipper'', she "showed that she had not only an excellent voice, but the grace and action which only long experience and study can give the artist."

Return to circus life and public safety education

When George Starr was offered a position as managing director of Barnum & Bailey, she decided to reenter circus life. She also began using her expertise to educate the public and public safety workers about the usefulness and potential of safety nets, for example to catch people jumping out of burning buildings. Dressed in normal clothing, including jewellery and a hat, she would throw herself out of a building window into a net. An 1892 edition of ''The West Australian'' describes one such exhibition: "There was never a more fearless woman gymnast than this Zazel, who jumped nonchalantly from a fourth storey window into a net to illustrate the possibilities of the net as a means of saving life. She tied a stout cord about her skirts, and throwing her head up and backward, she sprang to the centre of the net as confidently and as gracefully as my lady springs from her carriage." She volunteered her time to advocate for the use of nets as life-saving tools for several years. In addition to performing stunts, she wrote on the subject for people who live in large buildings and worked with ''The Evening Sun'' to publicise her ideas, sparking conversation throughout the US. According to the ''Clipper'', "she received the thanks of the New York Fire Department for her bravery and advice, and the press unite in editorially praising her actions." In 1891, while touring the United States with Adam Forepaugh's circus, she nearly died during a show inNew Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. She performed with the cannon as well as on a tight wire. The wire was about 40 feet off the ground, running from the side of the circus tent to two poles braced together in the centre, fit with a platform. According to a witness interviewed in the ''Mackay Mercury'', the poles were supposed to be fastened together with a steel band, but it was accidentally left off. When she was out on the wire, starting to put up an umbrella, she signalled to her coworkers, who thought she wanted them to tighten the wire. When they did so, the poles came apart and Richter fell to the ground. She landed on her hands and knees, and one of the poles fell on her back. When the poles were moved and someone picked her up, her body could not straighten out. Two men pulled her shoulders and legs to straighten out her appearance. The crowd panicked and she was heard screaming. The witness said it was "the most horrible accident I ever witnessed ... and I have seen a good many accidents in my day." She had broken her back. Local medical professionals provided short-term treatment before she was taken to facilities in New York. The accident effectively retired her from her circus career, and she spent several months in a suspended full body cast.

Later life

At some point Rossa and her husband moved back to England, living in a house inUpper Norwood

Upper Norwood is an area of south London, England, within the London Boroughs of Bromley, Croydon, Lambeth and Southwark. It is north of Croydon and the eastern part of it is better known as the Crystal Palace area.

Upper Norwood is situated ...

. He died in 1915 and requested that his ashes be spread to the "four winds" on the boat ride between the UK and US. British laws did not allow it, but she fulfilled his request secretly the following year, and then returned to England. In an update in a 1933 issue of ''The Bystander

''The Bystander'' was a British weekly tabloid magazine that featured reviews, topical drawings, cartoons and short stories. Published from Fleet Street, it was established in 1903 by George Holt Thomas. Its first editor, William Comyns Beaumon ...

'', she said that she was living on her own in Southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

, enjoying playing roulette

Roulette is a casino game named after the French word meaning ''little wheel'' which was likely developed from the Italian game Biribi''.'' In the game, a player may choose to place a bet on a single number, various groupings of numbers, the ...

when she had the opportunity. She died on 8 December 1937 at Camberwell House hospital in Peckham

Peckham () is a district in southeast London, within the London Borough of Southwark. It is south-east of Charing Cross. At the United Kingdom Census 2001, 2001 Census the Peckham ward had a population of 14,720.

History

"Peckham" is a Saxon p ...

.

Image and legacy

Press coverage of Richter's performances remarked on the impressive spectacle of the act and her fearlessness and athleticism. ''The West Australian'' wrote that "there was never a more fearless woman gymnast" and said that "fear was to her an unknown quantity". That she also jumped out of buildings to demonstrate the functionality of a safety net further established that she was brave even outside of the confines of a circus tent. The ''Clipper'' said that "personally Zazel is bright, intelligent and noted for her acts of charity."

Though young, Richter was sexualised in advertising materials from the time of her earliest Zazel performances. Whereas ''The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News'' explained that women may appreciate her athleticism, it also provided several descriptions of her "most perfect" figure. Brian Tyson speculated that, looking at the advertising materials, some of the act's appeal may have been because "in order to fit into the cannon, she had to shed most of her Victorian clothing." The painter

Press coverage of Richter's performances remarked on the impressive spectacle of the act and her fearlessness and athleticism. ''The West Australian'' wrote that "there was never a more fearless woman gymnast" and said that "fear was to her an unknown quantity". That she also jumped out of buildings to demonstrate the functionality of a safety net further established that she was brave even outside of the confines of a circus tent. The ''Clipper'' said that "personally Zazel is bright, intelligent and noted for her acts of charity."

Though young, Richter was sexualised in advertising materials from the time of her earliest Zazel performances. Whereas ''The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News'' explained that women may appreciate her athleticism, it also provided several descriptions of her "most perfect" figure. Brian Tyson speculated that, looking at the advertising materials, some of the act's appeal may have been because "in order to fit into the cannon, she had to shed most of her Victorian clothing." The painter George Frederic Watts

George Frederic Watts (23 February 1817, in London – 1 July 1904) was a British painter and sculptor associated with the Symbolist movement. He said "I paint ideas, not things." Watts became famous in his lifetime for his allegorical work ...

asserted both that she was "the bravest woman I ever saw" and that her "form asthe most perfect he ever saw." When Watts asked her to sit for a portrait, her sister came along as a chaperone. Richter told ''The Bystander'' that at some point she asked her manager, likely Farini, whether she should donate Watts' portrait to the National Portrait Gallery. "He just laughed and said 'whatever would they want in the National Gallery with a picture of ''you''!'". the Gallery has three portraits of her in its collections: two lithographs by Alfred Concanen

Alfred Concanen (1835 – 10 December 1886) was, for over twenty-five years, one of the leading lithographers of the Victorian era, best remembered for his illustrated sheet music covers for songs made popular by famous music hall performers ...

and another by an unknown artist.

According to historians Janet Davis and Peta Tait, circus performers like Richter challenged stereotypes of femininity through acts that demonstrated unabashed feats of strength and agility. Some began to think she was actually a man dressed like a woman. Tait argued that the cannon spectacle, typically at the end of a show, served not only to provide a powerful conclusion but also to balance her other acts' more physical displays of athleticism with a more feminised, relatively passive helplessness — "a beautiful lady shot from a monstrous cannon." Shane Peacock's description of the show also highlights this dynamic: "Farini stood at the cannon, looking evil in his black beard, commanding the sweet, beautiful young Zazel to enter the mortar, and lighting the fuse to a great flourish, sending her across the quarium'sgreat hall into a net of his own invention." A commentator wrote extensively about her talents, appearance, and personality, saying that "her nature was as pure and sunshiny as her face and form were beautiful." Elaborating on her "purity," it went on to say that "princes sought her favor, but Zazel remained the pure girl and woman that she is today. Her purity was recognised by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

." Circus promoters highlighted their female stars' domesticity so as not to be seen as too revolutionary in terms of women's equality. Interviewers asked Richter about circus life, and her marriage to Starr facilitated discussion of the wholesome, quasi-traditional lives of the performers. She told one interviewer, speaking for women in the circus in general, that "the domestic instinct is very strong among circus women, for the reason that they are deprived of home life a great part of every year. She finds an outlet in many little ways, one of which is an appeal to the chef in charge of the dining car to be allowed to bake a cake." Combining statements about female performers' strength with flattering descriptions of their beauty and figure may have served a similar balancing function.

Richter's cannon act inspired a scene in the Henry James Byron

Henry James Byron (8 January 1835 – 11 April 1884) was a prolific English dramatist, as well as an editor, journalist, director, theatre manager, novelist and actor.

After an abortive start at a medical career, Byron struggled as a provincial ...

burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

, ''Little Doctor Faust'', when it played at the Gaiety Theatre. Nellie Farren

Ellen "Nellie" Farren (16 April 1848 – 29 April 1904) was an English actress and singer best known for her roles as the "principal boy" in musical burlesques at the Gaiety Theatre.

Born into a theatrical family, Farren began acting as a ch ...

's titular character would climb into a cannon, escaping through a hidden trap door in the stage while her costar, Edward O'Connor Terry

Edward O'Connor Terry (10 March 1844 – 2 April 1912) was an English actor, who became one of the most influential actors and comedians of the Victorian era.

Life and career

Terry was born in London, allegedly the illegitimate son of Feargu ...

, used a ramrod

A ramrod (or scouring stick) is a metal or wooden device used with muzzleloading firearms to push the projectile up against the propellant (mainly blackpowder). The ramrod was used with weapons such as muskets and cannons and was usually held ...

to simulate preparing the cannon to fire. After an explosion, she would run back in from the other side of the stage. This act, too, met with an accident when the trap door failed to open. When her costar began to use the ramrod, he realised he was hitting her rather than the cannon interior. Improvising, Terry asked "Are you in? Are you far in? Are you nearly far in?", a pun based on her name, "Nellie Farren." The scene as well as Terry's ad lib received such a strong response that they were retained in future performances.

'' Young Man's Fancy'', a 1939 British comedy film

A comedy film is a category of film which emphasizes humor. These films are designed to make the audience laugh through amusement. Films in this style traditionally have a happy ending (black comedy being an exception). Comedy is one of the ol ...

written and directed by Robert Stevenson Robert Stevenson may refer to:

* Robert Stevenson (actor and politician) (1915–1975), American actor and politician

* Robert Stevenson (civil engineer) (1772–1850), Scottish lighthouse engineer

* Robert Stevenson (director) (1905–1986), Engl ...

and co-written by Roland Pertwee

Roland Pertwee (15 May 1885 – 26 April 1963) was an English playwright, film and television screenwriter, director and actor. He was the father of ''Doctor Who'' actor Jon Pertwee and playwright and screenwriter Michael Pertwee. He was al ...

, featured a character based on Richter. Anna Lee

Anna Lee, MBE (born Joan Boniface Winnifrith; 2 January 1913 – 14 May 2004) was a British actress, labelled by studios "The British Bombshell".

Early life

Anna Lee was born Joan Boniface Winnifrith in Ightham, (pronounced 'Item'), Kent, the ...

played the role, Ada, an Irish human cannonball.

See also

* Dolly Shepherd * Edith Maud CookNotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Richter, Rossa Matilda 1863 births 1937 deaths British circus performers English stunt performers Entertainers from London 19th-century circus performers 20th-century circus performers