Ropes Creek Remnants on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A rope is a group of

A rope is a group of

Rope may be constructed of any long, stringy, fibrous material, but generally is constructed of certain

Rope may be constructed of any long, stringy, fibrous material, but generally is constructed of certain

Rope has been used since prehistory, prehistoric times. It is of paramount importance in fields as diverse as construction, seafaring, exploration, sports, theatre, and communications. Many types of knots have been developed to fasten with rope, join ropes, and utilize rope to generate mechanical advantage. Pulleys can redirect the pulling force of a rope in another direction, multiply its lifting or pulling power, and distribute a load over multiple parts of the same rope to increase safety and decrease wear.

Winches and capstan (nautical), capstans are machines designed to pull ropes.

Rope has been used since prehistory, prehistoric times. It is of paramount importance in fields as diverse as construction, seafaring, exploration, sports, theatre, and communications. Many types of knots have been developed to fasten with rope, join ropes, and utilize rope to generate mechanical advantage. Pulleys can redirect the pulling force of a rope in another direction, multiply its lifting or pulling power, and distribute a load over multiple parts of the same rope to increase safety and decrease wear.

Winches and capstan (nautical), capstans are machines designed to pull ropes.

The use of ropes for hunting, pulling, fastening, attaching, carrying, lifting, and climbing dates back to prehistoric times. It is likely that the earliest "ropes" were naturally occurring lengths of plant fibre, such as vines, followed soon by the first attempts at twisting and braiding these strands together to form the first proper ropes in the modern sense of the word. The earliest evidence of suspected rope is a very small fragment of three-ply cord from a Neanderthal site dated 50,000 years ago. This item was so small, it was only discovered and described with the help of a high power microscope. It is slightly thicker than the average thumb-nail, and would not stretch from edge-to-edge across a little finger-nail. There are other ways fibres can twist in nature, without deliberate construction.

A 40,000-year-old tool found in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany was identified in 2020 as very likely to be a tool for making rope. It is a strip of mammoth ivory with four holes drilled through it. Each hole is lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The grooves on three of the holes spiral in a clockwise direction from each side of the strip. The grooves on one hole spiral clockwise on one side, but counter-clockwise from the other side. Plant fibres would have been fed through the holes and the tool twisted, creating a single ply yarn. The spiral incisions would have tended to keep the fibres in place. Article has photograph of the Hohle Fels rope-making tool. But the incisions cannot impart any twist to the fibres pulled through the holes. Other 15,000-year-old objects with holes with spiral incisions, made from reindeer antler, found across Europe are thought to have been used to manipulate ropes, or perhaps some other purpose. They were originally named "Perforated_baton, batons", and thought possibly to have been carried as badges of rank.

Impressions of cordage found on Pit fired pottery, fired clay provide evidence of string and rope-making technology in Europe dating back 28,000 years. Fossilized fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about diameter" were found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dating to approximately 15,000 Before Christ, BC.J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), ''The History and Science of Knots'' (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

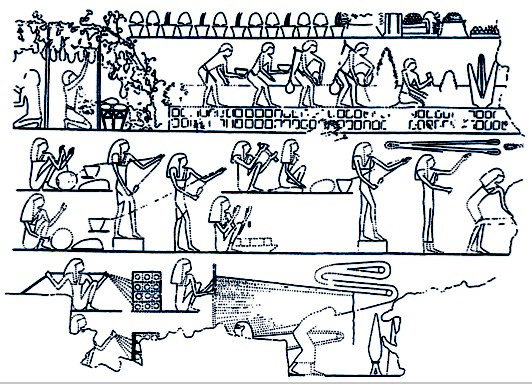

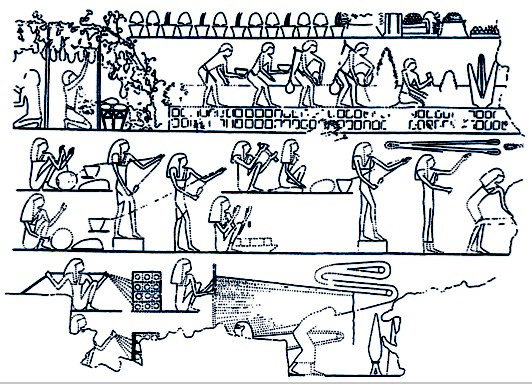

The ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilization to develop special tools to make rope. Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibres. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibres of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. The use of such ropes pulled by thousands of workers allowed the Egyptians to move the heavy stones required to build their monuments. Starting from approximately 2800 BC, rope made of

The use of ropes for hunting, pulling, fastening, attaching, carrying, lifting, and climbing dates back to prehistoric times. It is likely that the earliest "ropes" were naturally occurring lengths of plant fibre, such as vines, followed soon by the first attempts at twisting and braiding these strands together to form the first proper ropes in the modern sense of the word. The earliest evidence of suspected rope is a very small fragment of three-ply cord from a Neanderthal site dated 50,000 years ago. This item was so small, it was only discovered and described with the help of a high power microscope. It is slightly thicker than the average thumb-nail, and would not stretch from edge-to-edge across a little finger-nail. There are other ways fibres can twist in nature, without deliberate construction.

A 40,000-year-old tool found in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany was identified in 2020 as very likely to be a tool for making rope. It is a strip of mammoth ivory with four holes drilled through it. Each hole is lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The grooves on three of the holes spiral in a clockwise direction from each side of the strip. The grooves on one hole spiral clockwise on one side, but counter-clockwise from the other side. Plant fibres would have been fed through the holes and the tool twisted, creating a single ply yarn. The spiral incisions would have tended to keep the fibres in place. Article has photograph of the Hohle Fels rope-making tool. But the incisions cannot impart any twist to the fibres pulled through the holes. Other 15,000-year-old objects with holes with spiral incisions, made from reindeer antler, found across Europe are thought to have been used to manipulate ropes, or perhaps some other purpose. They were originally named "Perforated_baton, batons", and thought possibly to have been carried as badges of rank.

Impressions of cordage found on Pit fired pottery, fired clay provide evidence of string and rope-making technology in Europe dating back 28,000 years. Fossilized fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about diameter" were found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dating to approximately 15,000 Before Christ, BC.J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), ''The History and Science of Knots'' (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

The ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilization to develop special tools to make rope. Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibres. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibres of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. The use of such ropes pulled by thousands of workers allowed the Egyptians to move the heavy stones required to build their monuments. Starting from approximately 2800 BC, rope made of

Mendel I 016 r.jpg, A ropemaker at work,

German Ropemaker, around 1460-1480.png, A German ropemaker,

Turku Medieval Markets, twisting rope.jpg, Public demonstration of historical ropemaking technique

MaryRose-rope fragment.JPG, A piece of preserved rope found on board the 16th century carrack ''Mary Rose''

Repslagarbanan 1-Karlskrona.JPG, A ropewalk in Karlskrona, Sweden

Laid rope, also called twisted rope, is historically the prevalent form of rope, at least in modern Western culture, Western history. Common twisted rope generally consists of three strands and is normally right-laid, or given a final right-handed twist. The ISO 2 standard uses the Letter case, uppercase letters and to indicate the two possible directions of twist, as suggested by the direction of slant of the central portions of these two letters. The Chirality (physics), handedness of the twist is the direction of the twists as they progress away from an observer. Thus Z-twist rope is said to be Right-hand rule#Direction associated with a rotation, right-handed, and S-twist to be left-handed.

Twisted ropes are built up in three steps. First,

Laid rope, also called twisted rope, is historically the prevalent form of rope, at least in modern Western culture, Western history. Common twisted rope generally consists of three strands and is normally right-laid, or given a final right-handed twist. The ISO 2 standard uses the Letter case, uppercase letters and to indicate the two possible directions of twist, as suggested by the direction of slant of the central portions of these two letters. The Chirality (physics), handedness of the twist is the direction of the twists as they progress away from an observer. Thus Z-twist rope is said to be Right-hand rule#Direction associated with a rotation, right-handed, and S-twist to be left-handed.

Twisted ropes are built up in three steps. First,  Traditionally, a three strand laid rope is called a ''plain-'' or ''hawser-laid'', a four strand rope is called ''shroud-laid'', and a larger rope formed by counter-twisting three or more multi-strand ropes together is called ''cable-laid''. Cable-laid rope is sometimes clamped to maintain a tight counter-twist rendering the resulting nautical cable, cable virtually waterproof. Without this feature, deep water sailing (before the advent of steel chains and other lines) was largely impossible, as any appreciable length of rope for anchoring or ship to ship transfers, would become too waterlogged – and therefore too heavy – to lift, even with the aid of a capstan or windlass.

One property of laid rope is partial untwisting when used. This can cause spinning of suspended loads, or Deformation (mechanics), stretching, wikt:kink, kinking, or wikt:hockle, hockling of the rope itself. An additional drawback of twisted construction is that every fibre is exposed to abrasion numerous times along the length of the rope. This means that the rope can degrade to numerous inch-long fibre fragments, which is not easily detected visually.

Twisted ropes have a preferred direction for coiling. Normal right-laid rope should be coiled clockwise, to prevent kinking. Coiling this way imparts a twist to the rope. Rope of this type must be Whipped rope, bound at its ends by some means to prevent untwisting.

Traditionally, a three strand laid rope is called a ''plain-'' or ''hawser-laid'', a four strand rope is called ''shroud-laid'', and a larger rope formed by counter-twisting three or more multi-strand ropes together is called ''cable-laid''. Cable-laid rope is sometimes clamped to maintain a tight counter-twist rendering the resulting nautical cable, cable virtually waterproof. Without this feature, deep water sailing (before the advent of steel chains and other lines) was largely impossible, as any appreciable length of rope for anchoring or ship to ship transfers, would become too waterlogged – and therefore too heavy – to lift, even with the aid of a capstan or windlass.

One property of laid rope is partial untwisting when used. This can cause spinning of suspended loads, or Deformation (mechanics), stretching, wikt:kink, kinking, or wikt:hockle, hockling of the rope itself. An additional drawback of twisted construction is that every fibre is exposed to abrasion numerous times along the length of the rope. This means that the rope can degrade to numerous inch-long fibre fragments, which is not easily detected visually.

Twisted ropes have a preferred direction for coiling. Normal right-laid rope should be coiled clockwise, to prevent kinking. Coiling this way imparts a twist to the rope. Rope of this type must be Whipped rope, bound at its ends by some means to prevent untwisting.

While rope may be made from three or more strands, modern braided rope consists of a braided (tubular) jacket over strands of fibre (these may also be braided). Some forms of braided rope with untwisted cores have a particular advantage; they do not impart an additional twisting force when they are stressed. The lack of added twisting forces is an advantage when a load is freely suspended, as when a rope is used for Abseiling, rappelling or to suspend an arborist. Other specialized cores reduce the shock from arresting a fall when used as a part of a personal or group safety system.

Braided ropes are generally made from nylon, polyester, polypropylene or high performance fibres such as Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, high modulus polyethylene (HMPE) and aramid. Nylon is chosen for its strength and elastic stretch properties. However, nylon absorbs water and is 10–15% weaker when wet. Polyester is about 90% as strong as nylon but stretches less under load and is not affected by water. It has somewhat better UV resistance, and is more abrasion resistant. Polypropylene is preferred for low cost and light weight (it floats on water) but it has limited resistance to ultraviolet light, is susceptible to friction and has a poor heat resistance.

Braided ropes (and objects like garden hose (tubing), hoses, optical fibre, fibre optic or coaxial cable, coaxial cables, etc.) that have no ''lay'' (or inherent twist) uncoil better if each alternate loop is twisted in the opposite direction, such as in figure-eight coils, where the twist reverses regularly and essentially cancels out.

Single braid consists of an even number of strands, eight or twelve being typical, braided into a circular pattern with half of the strands going clockwise and the other half going anticlockwise. The strands can interlock with either twill or plain weave. The central void may be large or small; in the former case the term ''hollow braid'' is sometimes preferred.

Double braid, also called braid on braid, consists of an inner braid filling the central void in an outer braid, that may be of the same or different material. Often the inner braid fibre is chosen for strength while the outer braid fibre is chosen for abrasion resistance.

In solid braid, the strands all travel the same direction, clockwise or anticlockwise, and alternate between forming the outside of the rope and the interior of the rope. This construction is popular for general purpose utility rope but rare in specialized high performance line.

Kernmantle rope has a core (kern) of long twisted fibres in the center, with a braided outer sheath or mantle of weaving, woven fibres. The kern provides most of the strength (about 70%), while the mantle protects the kern and determines the handling properties of the rope (how easy it is to hold, to tie knots in, and so on). In dynamic rope, dynamic climbing line, core fibres are usually twisted to make the rope more elastic. Static kernmantle ropes are made with untwisted core fibres and tighter braid, which causes them to be stiffer in addition to limiting the stretch.

While rope may be made from three or more strands, modern braided rope consists of a braided (tubular) jacket over strands of fibre (these may also be braided). Some forms of braided rope with untwisted cores have a particular advantage; they do not impart an additional twisting force when they are stressed. The lack of added twisting forces is an advantage when a load is freely suspended, as when a rope is used for Abseiling, rappelling or to suspend an arborist. Other specialized cores reduce the shock from arresting a fall when used as a part of a personal or group safety system.

Braided ropes are generally made from nylon, polyester, polypropylene or high performance fibres such as Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, high modulus polyethylene (HMPE) and aramid. Nylon is chosen for its strength and elastic stretch properties. However, nylon absorbs water and is 10–15% weaker when wet. Polyester is about 90% as strong as nylon but stretches less under load and is not affected by water. It has somewhat better UV resistance, and is more abrasion resistant. Polypropylene is preferred for low cost and light weight (it floats on water) but it has limited resistance to ultraviolet light, is susceptible to friction and has a poor heat resistance.

Braided ropes (and objects like garden hose (tubing), hoses, optical fibre, fibre optic or coaxial cable, coaxial cables, etc.) that have no ''lay'' (or inherent twist) uncoil better if each alternate loop is twisted in the opposite direction, such as in figure-eight coils, where the twist reverses regularly and essentially cancels out.

Single braid consists of an even number of strands, eight or twelve being typical, braided into a circular pattern with half of the strands going clockwise and the other half going anticlockwise. The strands can interlock with either twill or plain weave. The central void may be large or small; in the former case the term ''hollow braid'' is sometimes preferred.

Double braid, also called braid on braid, consists of an inner braid filling the central void in an outer braid, that may be of the same or different material. Often the inner braid fibre is chosen for strength while the outer braid fibre is chosen for abrasion resistance.

In solid braid, the strands all travel the same direction, clockwise or anticlockwise, and alternate between forming the outside of the rope and the interior of the rope. This construction is popular for general purpose utility rope but rare in specialized high performance line.

Kernmantle rope has a core (kern) of long twisted fibres in the center, with a braided outer sheath or mantle of weaving, woven fibres. The kern provides most of the strength (about 70%), while the mantle protects the kern and determines the handling properties of the rope (how easy it is to hold, to tie knots in, and so on). In dynamic rope, dynamic climbing line, core fibres are usually twisted to make the rope more elastic. Static kernmantle ropes are made with untwisted core fibres and tighter braid, which causes them to be stiffer in addition to limiting the stretch.

The sport of rock climbing uses what is termed Dynamic rope, "dynamic" rope, an elastic rope which stretches under load to absorb the energy generated in Fall arrest, arresting a fall without creating forces high enough to injure the climber. Such ropes are of Kernmantle rope, kernmantle construction, as described #kernmantle, below.

Conversely, Static rope, "static" ropes have minimal stretch and are not designed to arrest free falls. They are used in caving, rappelling, rescue applications, and industries such as window washing.

The UIAA, in concert with the European Committee for Standardization, CEN, sets climbing-rope standards and oversees testing. Any rope bearing a GUIANA or CE certification tag is suitable for climbing. Climbing ropes cut easily when under load. Keeping them away from sharp rock edges is imperative. Previous falls arrested by a rope, damage to its sheath, and contamination by dirt or solvents all weaken a rope and can render it unsuitable for further sport use.

Rock climbing ropes are designated as suitable for single, double or twin use. A single rope is the most common, and is intended to be used by itself. These range in thickness from roughly . Smaller diameter ropes are lighter, but wear out faster.

Double ropes are thinner than single, usually and under, and are intended for use in pairs. These offer a greater margin of safety against cutting, since it is unlikely that both ropes will be cut, but complicate both belaying and leading. Double ropes may be clipped into alternating pieces of protection, allowing each to stay straighter and reduce both individual and total rope drag.

Twin ropes are thin ropes which must be clipped into the same piece of protection, in effect being treated as a single strand. This adds security in situations where a rope may get cut. However new lighter-weight ropes with greater safety have virtually replaced this type of rope.

The butterfly coil, butterfly and mountaineer's coil, alpine coils are methods of coiling a rope for carrying.

The sport of rock climbing uses what is termed Dynamic rope, "dynamic" rope, an elastic rope which stretches under load to absorb the energy generated in Fall arrest, arresting a fall without creating forces high enough to injure the climber. Such ropes are of Kernmantle rope, kernmantle construction, as described #kernmantle, below.

Conversely, Static rope, "static" ropes have minimal stretch and are not designed to arrest free falls. They are used in caving, rappelling, rescue applications, and industries such as window washing.

The UIAA, in concert with the European Committee for Standardization, CEN, sets climbing-rope standards and oversees testing. Any rope bearing a GUIANA or CE certification tag is suitable for climbing. Climbing ropes cut easily when under load. Keeping them away from sharp rock edges is imperative. Previous falls arrested by a rope, damage to its sheath, and contamination by dirt or solvents all weaken a rope and can render it unsuitable for further sport use.

Rock climbing ropes are designated as suitable for single, double or twin use. A single rope is the most common, and is intended to be used by itself. These range in thickness from roughly . Smaller diameter ropes are lighter, but wear out faster.

Double ropes are thinner than single, usually and under, and are intended for use in pairs. These offer a greater margin of safety against cutting, since it is unlikely that both ropes will be cut, but complicate both belaying and leading. Double ropes may be clipped into alternating pieces of protection, allowing each to stay straighter and reduce both individual and total rope drag.

Twin ropes are thin ropes which must be clipped into the same piece of protection, in effect being treated as a single strand. This adds security in situations where a rope may get cut. However new lighter-weight ropes with greater safety have virtually replaced this type of rope.

The butterfly coil, butterfly and mountaineer's coil, alpine coils are methods of coiling a rope for carrying.

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 2D top view.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 2D top view zoom.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 2D lateral view.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 2D lateral view 2.jpg

Micro-CT Rope HighRes 2D Top 2050x2050.ogv

Micro-CT 2D top view flight-through of a braided polymer climbing rope Zoom.ogg

Micro-CT Rope HighRes 2D Right 2560x550 750f 25fps.ogv

Micro-CT Rope HighRes 2D Rotation 2560x550 750f 25fps.ogv

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 02.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 03.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 05.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 07.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 08.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 10.jpg

Micro-CT braided polymer rope 3D 11.jpg

Micro-CT Rope HighRes 3D.ogv

Rope made from

Rope made from

Ropewalk: A Cordage Engineer's Journey Through History

History of ropemaking resource and nonprofit documentary film

Watch ''How Do They Braid Rope?''

{{Authority control Ropes, Articles containing video clips Climbing equipment Mountaineering equipment Primitive technology

A rope is a group of

A rope is a group of yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manufact ...

s, plies, fibre

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorporate ...

s, or strands that are twisted or braid

A braid (also referred to as a plait) is a complex structure or pattern formed by interlacing two or more strands of flexible material such as textile yarns, wire, or hair.

The simplest and most common version is a flat, solid, three-strande ...

ed together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarly constructed cord, string

String or strings may refer to:

*String (structure), a long flexible structure made from threads twisted together, which is used to tie, bind, or hang other objects

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Strings'' (1991 film), a Canadian anim ...

, and twine

Twine is a strong Thread (yarn), thread, light String (cord), string or cord composed of two or more thinner strands twisted, and then twisted together (Plying, plied). The strands are plied in the opposite direction to that of their twist, whic ...

.

Construction

natural

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

or synthetic Synthetic things are composed of multiple parts, often with the implication that they are artificial. In particular, 'synthetic' may refer to:

Science

* Synthetic chemical or compound, produced by the process of chemical synthesis

* Synthetic o ...

fibres. Synthetic fibre ropes are significantly stronger than their natural fibre counterparts, they have a higher tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

, they are more resistant to rotting than ropes created from natural fibres, and they can be made to float on water. But synthetic ropes also possess certain disadvantages, including slipperiness, and some can be damaged more easily by UV light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

.

Common natural fibres for rope are Manila hemp

Manila hemp, also known as abacá, is a type of buff-colored fiber obtained from ''Musa textilis'' (a relative of edible bananas), which is likewise called Manila hemp as well as abacá. It is mostly used for pulping for a range of uses, inclu ...

, hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

, linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

, cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

, coir, jute, straw, and sisal. Synthetic fibres in use for rope-making include polypropylene, nylon, polyesters (e.g. polyethylene terephthalate, PET, Liquid Crystal Polymer, LCP, Vectran), polyethylene (e.g. Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, Dyneema and Spectra), Aramids (e.g. Twaron, Technora and Kevlar) and Acrylate polymer, acrylics (e.g. Dralon). Some ropes are constructed of mixtures of several fibres or use co-polymer fibres. Wire rope is made of steel or other metal alloys. Ropes have been constructed of other fibrous materials such as silk, wool, and hair, but such ropes are not generally available. Rayon is a regenerated fibre used to make decorative rope.

The twist of the strands in a twisted or braided rope serves not only to keep a rope together, but enables the rope to more evenly distribute tension among the individual strands. Without any twist in the rope, the shortest strand(s) would always be supporting a much higher proportion of the total load.

Size measurement

Because rope has a long history, many systems have been used to specify the size of a rope. In systems that use the inch (Imperial and US customary measurement systems), large ropes over diameter – such as those used on ships – are measured by their circumference in inches; smaller ropes have a nominal diameter based on the circumference divided by three (as a rough approximation of pi). In the metric system of measurement, the nominal diameter is given in millimetres. The current preferred international standard for rope sizes is to give the mass per unit length, in kilograms per metre. However, even sources otherwise using metric units may still give a "rope number" for large ropes, which is the circumference in inches.Use

History

The use of ropes for hunting, pulling, fastening, attaching, carrying, lifting, and climbing dates back to prehistoric times. It is likely that the earliest "ropes" were naturally occurring lengths of plant fibre, such as vines, followed soon by the first attempts at twisting and braiding these strands together to form the first proper ropes in the modern sense of the word. The earliest evidence of suspected rope is a very small fragment of three-ply cord from a Neanderthal site dated 50,000 years ago. This item was so small, it was only discovered and described with the help of a high power microscope. It is slightly thicker than the average thumb-nail, and would not stretch from edge-to-edge across a little finger-nail. There are other ways fibres can twist in nature, without deliberate construction.

A 40,000-year-old tool found in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany was identified in 2020 as very likely to be a tool for making rope. It is a strip of mammoth ivory with four holes drilled through it. Each hole is lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The grooves on three of the holes spiral in a clockwise direction from each side of the strip. The grooves on one hole spiral clockwise on one side, but counter-clockwise from the other side. Plant fibres would have been fed through the holes and the tool twisted, creating a single ply yarn. The spiral incisions would have tended to keep the fibres in place. Article has photograph of the Hohle Fels rope-making tool. But the incisions cannot impart any twist to the fibres pulled through the holes. Other 15,000-year-old objects with holes with spiral incisions, made from reindeer antler, found across Europe are thought to have been used to manipulate ropes, or perhaps some other purpose. They were originally named "Perforated_baton, batons", and thought possibly to have been carried as badges of rank.

Impressions of cordage found on Pit fired pottery, fired clay provide evidence of string and rope-making technology in Europe dating back 28,000 years. Fossilized fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about diameter" were found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dating to approximately 15,000 Before Christ, BC.J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), ''The History and Science of Knots'' (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

The ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilization to develop special tools to make rope. Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibres. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibres of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. The use of such ropes pulled by thousands of workers allowed the Egyptians to move the heavy stones required to build their monuments. Starting from approximately 2800 BC, rope made of

The use of ropes for hunting, pulling, fastening, attaching, carrying, lifting, and climbing dates back to prehistoric times. It is likely that the earliest "ropes" were naturally occurring lengths of plant fibre, such as vines, followed soon by the first attempts at twisting and braiding these strands together to form the first proper ropes in the modern sense of the word. The earliest evidence of suspected rope is a very small fragment of three-ply cord from a Neanderthal site dated 50,000 years ago. This item was so small, it was only discovered and described with the help of a high power microscope. It is slightly thicker than the average thumb-nail, and would not stretch from edge-to-edge across a little finger-nail. There are other ways fibres can twist in nature, without deliberate construction.

A 40,000-year-old tool found in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany was identified in 2020 as very likely to be a tool for making rope. It is a strip of mammoth ivory with four holes drilled through it. Each hole is lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The grooves on three of the holes spiral in a clockwise direction from each side of the strip. The grooves on one hole spiral clockwise on one side, but counter-clockwise from the other side. Plant fibres would have been fed through the holes and the tool twisted, creating a single ply yarn. The spiral incisions would have tended to keep the fibres in place. Article has photograph of the Hohle Fels rope-making tool. But the incisions cannot impart any twist to the fibres pulled through the holes. Other 15,000-year-old objects with holes with spiral incisions, made from reindeer antler, found across Europe are thought to have been used to manipulate ropes, or perhaps some other purpose. They were originally named "Perforated_baton, batons", and thought possibly to have been carried as badges of rank.

Impressions of cordage found on Pit fired pottery, fired clay provide evidence of string and rope-making technology in Europe dating back 28,000 years. Fossilized fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about diameter" were found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dating to approximately 15,000 Before Christ, BC.J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), ''The History and Science of Knots'' (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

The ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilization to develop special tools to make rope. Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibres. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibres of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. The use of such ropes pulled by thousands of workers allowed the Egyptians to move the heavy stones required to build their monuments. Starting from approximately 2800 BC, rope made of hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

fibres was in use in China. Rope and the craft of rope making spread throughout Asia, India, and Europe over the next several thousand years.

From the Middle Ages until the 18th century, in Europe ropes were constructed in ropewalks, very long buildings where strands the full length of the rope were spread out and then ''laid up'' or twisted together to form the rope. The cable length was thus set by the length of the available rope walk. This is related to the unit of length termed ''cable length''. This allowed for long ropes of up to long or longer to be made. These long ropes were necessary in shipping as short ropes would require Rope splicing, splicing to make them long enough to use for sheet (sailing), sheets and halyards. The strongest form of splicing is the short splice, which doubles the cross-sectional area of the rope at the area of the splice, which would cause problems in running the line through pulleys. Any splices narrow enough to maintain smooth running would be less able to support the required weight.

Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of a concept for a ropemaking machine, but it was never built. Remarkable feats of construction were accomplished using rope but without advanced technology: In 1586, Domenico Fontana erected the 327 ton obelisk on Rome's Saint Peter's Square with a concerted effort of 900 men, 75 horses, and countless pulleys and meters of rope. By the late 18th century several working machines had been built and patented.

Some rope is still made from natural fibres, such as coir and sisal, despite the dominance of synthetic fibres such as nylon and polypropylene, which have become increasingly popular since the 1950s.

Nylon was discovered in the late 1930s and was first introduced into fiber ropes during World War II. Indeed, the first synthetic fiber ropes were small braided parachute cords and three-strand tow ropes for gliders, made of nylon during World War II.

Styles of rope

Laid or twisted rope

Laid rope, also called twisted rope, is historically the prevalent form of rope, at least in modern Western culture, Western history. Common twisted rope generally consists of three strands and is normally right-laid, or given a final right-handed twist. The ISO 2 standard uses the Letter case, uppercase letters and to indicate the two possible directions of twist, as suggested by the direction of slant of the central portions of these two letters. The Chirality (physics), handedness of the twist is the direction of the twists as they progress away from an observer. Thus Z-twist rope is said to be Right-hand rule#Direction associated with a rotation, right-handed, and S-twist to be left-handed.

Twisted ropes are built up in three steps. First,

Laid rope, also called twisted rope, is historically the prevalent form of rope, at least in modern Western culture, Western history. Common twisted rope generally consists of three strands and is normally right-laid, or given a final right-handed twist. The ISO 2 standard uses the Letter case, uppercase letters and to indicate the two possible directions of twist, as suggested by the direction of slant of the central portions of these two letters. The Chirality (physics), handedness of the twist is the direction of the twists as they progress away from an observer. Thus Z-twist rope is said to be Right-hand rule#Direction associated with a rotation, right-handed, and S-twist to be left-handed.

Twisted ropes are built up in three steps. First, fibre

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorporate ...

s are gathered and Spinning (textiles), spun into yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manufact ...

s. A number of these yarns are then formed into strands by twisting. The strands are then twisted together to lay the rope. The twist of the yarn is opposite to that of the strand, and that in turn is opposite to that of the rope. It is this counter-twist, introduced with each successive operation, which holds the final rope together as a stable, unified object.

Traditionally, a three strand laid rope is called a ''plain-'' or ''hawser-laid'', a four strand rope is called ''shroud-laid'', and a larger rope formed by counter-twisting three or more multi-strand ropes together is called ''cable-laid''. Cable-laid rope is sometimes clamped to maintain a tight counter-twist rendering the resulting nautical cable, cable virtually waterproof. Without this feature, deep water sailing (before the advent of steel chains and other lines) was largely impossible, as any appreciable length of rope for anchoring or ship to ship transfers, would become too waterlogged – and therefore too heavy – to lift, even with the aid of a capstan or windlass.

One property of laid rope is partial untwisting when used. This can cause spinning of suspended loads, or Deformation (mechanics), stretching, wikt:kink, kinking, or wikt:hockle, hockling of the rope itself. An additional drawback of twisted construction is that every fibre is exposed to abrasion numerous times along the length of the rope. This means that the rope can degrade to numerous inch-long fibre fragments, which is not easily detected visually.

Twisted ropes have a preferred direction for coiling. Normal right-laid rope should be coiled clockwise, to prevent kinking. Coiling this way imparts a twist to the rope. Rope of this type must be Whipped rope, bound at its ends by some means to prevent untwisting.

Traditionally, a three strand laid rope is called a ''plain-'' or ''hawser-laid'', a four strand rope is called ''shroud-laid'', and a larger rope formed by counter-twisting three or more multi-strand ropes together is called ''cable-laid''. Cable-laid rope is sometimes clamped to maintain a tight counter-twist rendering the resulting nautical cable, cable virtually waterproof. Without this feature, deep water sailing (before the advent of steel chains and other lines) was largely impossible, as any appreciable length of rope for anchoring or ship to ship transfers, would become too waterlogged – and therefore too heavy – to lift, even with the aid of a capstan or windlass.

One property of laid rope is partial untwisting when used. This can cause spinning of suspended loads, or Deformation (mechanics), stretching, wikt:kink, kinking, or wikt:hockle, hockling of the rope itself. An additional drawback of twisted construction is that every fibre is exposed to abrasion numerous times along the length of the rope. This means that the rope can degrade to numerous inch-long fibre fragments, which is not easily detected visually.

Twisted ropes have a preferred direction for coiling. Normal right-laid rope should be coiled clockwise, to prevent kinking. Coiling this way imparts a twist to the rope. Rope of this type must be Whipped rope, bound at its ends by some means to prevent untwisting.

Braided rope

While rope may be made from three or more strands, modern braided rope consists of a braided (tubular) jacket over strands of fibre (these may also be braided). Some forms of braided rope with untwisted cores have a particular advantage; they do not impart an additional twisting force when they are stressed. The lack of added twisting forces is an advantage when a load is freely suspended, as when a rope is used for Abseiling, rappelling or to suspend an arborist. Other specialized cores reduce the shock from arresting a fall when used as a part of a personal or group safety system.

Braided ropes are generally made from nylon, polyester, polypropylene or high performance fibres such as Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, high modulus polyethylene (HMPE) and aramid. Nylon is chosen for its strength and elastic stretch properties. However, nylon absorbs water and is 10–15% weaker when wet. Polyester is about 90% as strong as nylon but stretches less under load and is not affected by water. It has somewhat better UV resistance, and is more abrasion resistant. Polypropylene is preferred for low cost and light weight (it floats on water) but it has limited resistance to ultraviolet light, is susceptible to friction and has a poor heat resistance.

Braided ropes (and objects like garden hose (tubing), hoses, optical fibre, fibre optic or coaxial cable, coaxial cables, etc.) that have no ''lay'' (or inherent twist) uncoil better if each alternate loop is twisted in the opposite direction, such as in figure-eight coils, where the twist reverses regularly and essentially cancels out.

Single braid consists of an even number of strands, eight or twelve being typical, braided into a circular pattern with half of the strands going clockwise and the other half going anticlockwise. The strands can interlock with either twill or plain weave. The central void may be large or small; in the former case the term ''hollow braid'' is sometimes preferred.

Double braid, also called braid on braid, consists of an inner braid filling the central void in an outer braid, that may be of the same or different material. Often the inner braid fibre is chosen for strength while the outer braid fibre is chosen for abrasion resistance.

In solid braid, the strands all travel the same direction, clockwise or anticlockwise, and alternate between forming the outside of the rope and the interior of the rope. This construction is popular for general purpose utility rope but rare in specialized high performance line.

Kernmantle rope has a core (kern) of long twisted fibres in the center, with a braided outer sheath or mantle of weaving, woven fibres. The kern provides most of the strength (about 70%), while the mantle protects the kern and determines the handling properties of the rope (how easy it is to hold, to tie knots in, and so on). In dynamic rope, dynamic climbing line, core fibres are usually twisted to make the rope more elastic. Static kernmantle ropes are made with untwisted core fibres and tighter braid, which causes them to be stiffer in addition to limiting the stretch.

While rope may be made from three or more strands, modern braided rope consists of a braided (tubular) jacket over strands of fibre (these may also be braided). Some forms of braided rope with untwisted cores have a particular advantage; they do not impart an additional twisting force when they are stressed. The lack of added twisting forces is an advantage when a load is freely suspended, as when a rope is used for Abseiling, rappelling or to suspend an arborist. Other specialized cores reduce the shock from arresting a fall when used as a part of a personal or group safety system.

Braided ropes are generally made from nylon, polyester, polypropylene or high performance fibres such as Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, high modulus polyethylene (HMPE) and aramid. Nylon is chosen for its strength and elastic stretch properties. However, nylon absorbs water and is 10–15% weaker when wet. Polyester is about 90% as strong as nylon but stretches less under load and is not affected by water. It has somewhat better UV resistance, and is more abrasion resistant. Polypropylene is preferred for low cost and light weight (it floats on water) but it has limited resistance to ultraviolet light, is susceptible to friction and has a poor heat resistance.

Braided ropes (and objects like garden hose (tubing), hoses, optical fibre, fibre optic or coaxial cable, coaxial cables, etc.) that have no ''lay'' (or inherent twist) uncoil better if each alternate loop is twisted in the opposite direction, such as in figure-eight coils, where the twist reverses regularly and essentially cancels out.

Single braid consists of an even number of strands, eight or twelve being typical, braided into a circular pattern with half of the strands going clockwise and the other half going anticlockwise. The strands can interlock with either twill or plain weave. The central void may be large or small; in the former case the term ''hollow braid'' is sometimes preferred.

Double braid, also called braid on braid, consists of an inner braid filling the central void in an outer braid, that may be of the same or different material. Often the inner braid fibre is chosen for strength while the outer braid fibre is chosen for abrasion resistance.

In solid braid, the strands all travel the same direction, clockwise or anticlockwise, and alternate between forming the outside of the rope and the interior of the rope. This construction is popular for general purpose utility rope but rare in specialized high performance line.

Kernmantle rope has a core (kern) of long twisted fibres in the center, with a braided outer sheath or mantle of weaving, woven fibres. The kern provides most of the strength (about 70%), while the mantle protects the kern and determines the handling properties of the rope (how easy it is to hold, to tie knots in, and so on). In dynamic rope, dynamic climbing line, core fibres are usually twisted to make the rope more elastic. Static kernmantle ropes are made with untwisted core fibres and tighter braid, which causes them to be stiffer in addition to limiting the stretch.

Other types

Plaited rope is made by braiding twisted strands, and is also called ''square braid''. It is not as round as twisted rope and coarser to the touch. It is less prone to kinking than twisted rope and, depending on the material, very flexible and therefore easy to handle and knot. This construction exposes all fibres as well, with the same drawbacks as described above. Brait rope is a combination of braided and plaited, a non-rotating alternative to laid three-strand ropes. Due to its excellent energy-absorption characteristics, it is often used by arborists. It is also a popular rope for anchoring and can be used as mooring warps. This type of construction was pioneered by Yale Cordage. Endless winding rope is made by winding single strands of high-performance yarns around two end terminations until the desired break strength or stiffness has been reached. This type of rope (often specified as cable to make the difference between a braided or twined construction) has the advantage of having no construction stretch as is the case with above constructions. Endless winding is pioneered by SmartRigging and FibreMax.Rock climbing

The sport of rock climbing uses what is termed Dynamic rope, "dynamic" rope, an elastic rope which stretches under load to absorb the energy generated in Fall arrest, arresting a fall without creating forces high enough to injure the climber. Such ropes are of Kernmantle rope, kernmantle construction, as described #kernmantle, below.

Conversely, Static rope, "static" ropes have minimal stretch and are not designed to arrest free falls. They are used in caving, rappelling, rescue applications, and industries such as window washing.

The UIAA, in concert with the European Committee for Standardization, CEN, sets climbing-rope standards and oversees testing. Any rope bearing a GUIANA or CE certification tag is suitable for climbing. Climbing ropes cut easily when under load. Keeping them away from sharp rock edges is imperative. Previous falls arrested by a rope, damage to its sheath, and contamination by dirt or solvents all weaken a rope and can render it unsuitable for further sport use.

Rock climbing ropes are designated as suitable for single, double or twin use. A single rope is the most common, and is intended to be used by itself. These range in thickness from roughly . Smaller diameter ropes are lighter, but wear out faster.

Double ropes are thinner than single, usually and under, and are intended for use in pairs. These offer a greater margin of safety against cutting, since it is unlikely that both ropes will be cut, but complicate both belaying and leading. Double ropes may be clipped into alternating pieces of protection, allowing each to stay straighter and reduce both individual and total rope drag.

Twin ropes are thin ropes which must be clipped into the same piece of protection, in effect being treated as a single strand. This adds security in situations where a rope may get cut. However new lighter-weight ropes with greater safety have virtually replaced this type of rope.

The butterfly coil, butterfly and mountaineer's coil, alpine coils are methods of coiling a rope for carrying.

The sport of rock climbing uses what is termed Dynamic rope, "dynamic" rope, an elastic rope which stretches under load to absorb the energy generated in Fall arrest, arresting a fall without creating forces high enough to injure the climber. Such ropes are of Kernmantle rope, kernmantle construction, as described #kernmantle, below.

Conversely, Static rope, "static" ropes have minimal stretch and are not designed to arrest free falls. They are used in caving, rappelling, rescue applications, and industries such as window washing.

The UIAA, in concert with the European Committee for Standardization, CEN, sets climbing-rope standards and oversees testing. Any rope bearing a GUIANA or CE certification tag is suitable for climbing. Climbing ropes cut easily when under load. Keeping them away from sharp rock edges is imperative. Previous falls arrested by a rope, damage to its sheath, and contamination by dirt or solvents all weaken a rope and can render it unsuitable for further sport use.

Rock climbing ropes are designated as suitable for single, double or twin use. A single rope is the most common, and is intended to be used by itself. These range in thickness from roughly . Smaller diameter ropes are lighter, but wear out faster.

Double ropes are thinner than single, usually and under, and are intended for use in pairs. These offer a greater margin of safety against cutting, since it is unlikely that both ropes will be cut, but complicate both belaying and leading. Double ropes may be clipped into alternating pieces of protection, allowing each to stay straighter and reduce both individual and total rope drag.

Twin ropes are thin ropes which must be clipped into the same piece of protection, in effect being treated as a single strand. This adds security in situations where a rope may get cut. However new lighter-weight ropes with greater safety have virtually replaced this type of rope.

The butterfly coil, butterfly and mountaineer's coil, alpine coils are methods of coiling a rope for carrying.

Gallery of µCT/micro-CT images and animations

2D images / sections

2D flight-throughs/sections

3D renderings

3D flight-throughs/sections

Handling

Rope made from

Rope made from hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

, cotton or nylon is generally stored in a cool dry place for proper storage. To prevent kinking it is usually coiled. To prevent fraying or unravelling, the ends of a rope are bound with twine (whipping knot, whipping), tape, or heat shrink tubing. The ends of plastic fibre ropes are often melted and fused solid; however, the rope and knotting expert Geoffrey Budworth warns against this practice thus:

''Sealing rope ends this way is lazy and dangerous.'' A tugboat operator once sliced the palm of his hand open down to the sinews after the hardened (and obviously ''sharp'') end of a rope that had been heat-sealed pulled through his grasp. There is no substitute for a properly made whipping.If a load-bearing rope gets a sharp or sudden jolt or the rope shows signs of deteriorating, it is recommended that the rope be replaced immediately and should be discarded or only used for non-load-bearing tasks. The average rope life-span is 5 years. Serious inspection should be given to line after that point. However, the use to which a rope is put affects frequency of inspection. Rope used in mission-critical applications, such as mooring lines or running rigging, should be regularly inspected on a much shorter timescale than this, and rope used in life-critical applications such as mountain climbing should be inspected on a far more frequent basis, up to and including before each use. Avoid stepping on climbing rope, as this might force tiny pieces of rock through the sheath, which can eventually deteriorate the core of the rope. Ropes may be flemished into coils on deck for safety, presentation, and tidiness. Many types of filaments in ropes are weakened by corrosive liquids, solvents, and high temperatures. Such damage is particularly treacherous because it is often invisible to the eye. Shock loading should be avoided with general use ropes, as it can damage them. All ropes should be used within a safe working load, which is much less than their breaking strength. A rope under tension – particularly if it has a great deal of elasticity – can be dangerous if parted. Care should be taken around lines under load.

Terminology

"Rope" is a material, and a tool. When it is assigned a specific function it is often referred to as a "line", especially in nautical usage. A line may get a further distinction, for example sail control lines are known as “sheets” (e.g. A jib sheet). A halyard is a line used to raise and lower a sail, typically with a shackle on its sail end. Other maritime examples of “lines” include anchor line, mooring line, fishing line, . Common items include clothesline and a chalk line. In some marine uses the term rope is retained, such as man rope, bolt rope, and bell rope.See also

* * (splicing tool) * * * * * * Mooring#Mooring line materials, Mooring line materials * * * * (in theatre fly system) * * * * * * * *References

Sources

* Gaitzsch, W. ''Antike Korb- und Seilerwaren'', Schriften des Limesmuseums Aalen Nr. 38, 1986 * Gubser, T. ''Die bäuerliche Seilerei'', G. Krebs AG, Basel, 1965 * Hearle, John W. S. & O'Hear & McKenna, N. H. A. ''Handbook of Fibre Rope Technology'', CRC Press, 2004 * Lane, Frederic Chapin, 1932. ''The Rope Factory and Hemp Trade of Venice in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries'', Journal of Economic and Business History, Vol. 4 No. 4 Suppl. (August 1932). * Militzer-Schwenger, L.: ''Handwerkliche Seilherstellung'', Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, 1992 * Nilson, A. ''Studier i svenskt repslageri'', Stockholm, 1961 * Pierer, H.A. ''Universal-Lexikon'', Altenburg, 1845 * Plymouth Cordage Company, 1931. ''The Story of Rope; The History and the Modern Development of Rope-Making'', Plymouth Cordage Company, North Plymouth, Massachusetts * Sanctuary, Anthony, 1996.'' Rope, Twine and Net Making'', Shire Publications Ltd., Cromwell House, Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire. * Schubert, Pit. ''Sicherheit und Risiko in Fels und Eis'', Munich, 1998 * Smith, Bruce & Padgett, Allen, 1996. ''On Rope. North American Vertical Rope Techniques'', National Speleological Society, Huntsville, Alabama. * Strunk, P.; Abels, J. ''Das große Abenteuer 2.Teil'', Verlag Karl Wenzel, Marburg, 1986. * Teeter, Emily, 1987. ''Techniques and Terminology of Rope-Making in Ancient Egypt'', Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 73 (1987). * Tyson, William, no date. ''Rope, a History of the Hard Fibre Cordage Industry in the United Kingdom'', Wheatland Journals, Ltd., London.Further reading

* *External links

Ropewalk: A Cordage Engineer's Journey Through History

History of ropemaking resource and nonprofit documentary film

Watch ''How Do They Braid Rope?''

{{Authority control Ropes, Articles containing video clips Climbing equipment Mountaineering equipment Primitive technology