Roman Republican Governors Of Gaul on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The early history of Romano-Celtic relations begins during a period of Gallic expansionism on the Italian peninsula, with the capture of Rome by Gauls in 390 BC (or more likely 387) and the suspiciously fortuitous rescue of the city by Camillus after the Romans had already surrendered. The Gauls who fought at the

The early history of Romano-Celtic relations begins during a period of Gallic expansionism on the Italian peninsula, with the capture of Rome by Gauls in 390 BC (or more likely 387) and the suspiciously fortuitous rescue of the city by Camillus after the Romans had already surrendered. The Gauls who fought at the

The Roman takeover of Cisalpine Gaul, or "Gaul on this side of the

The Roman takeover of Cisalpine Gaul, or "Gaul on this side of the

''Gallia Transalpina'' at first could refer broadly to "Gaul on the other side of the Alps," but after the conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the 120s BC came to specify the Roman province in the south (''Provincia nostra'', "our Province," hence

''Gallia Transalpina'' at first could refer broadly to "Gaul on the other side of the Alps," but after the conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the 120s BC came to specify the Roman province in the south (''Provincia nostra'', "our Province," hence

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

an governors

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political_regions, political region, ranking under the Head of State, head of state and in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of ...

of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

were assigned to the province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul ( la, Gallia Cisalpina, also called ''Gallia Citerior'' or ''Gallia Togata'') was the part of Italy inhabited by Celts (Gauls) during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

After its conquest by the Roman Republic in the 200s BC it was con ...

(northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

) or to Transalpine Gaul

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in what is now Languedoc and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), because it was the ...

, the Mediterranean region of present-day France also called the Narbonensis

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in what is now Languedoc and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), because it was the ...

, though the latter term is sometimes reserved for a more strictly defined area administered from Narbonne

Narbonne (, also , ; oc, Narbona ; la, Narbo ; Late Latin:) is a commune in France, commune in Southern France in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region. It lies from Paris in the Aude Departments of Franc ...

(ancient Narbo). Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''Gallia'' can also refer in this period to greater Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

independent of Roman control, covering the remainder of France, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and parts of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, often distinguished as Gallia Comata

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during Re ...

and including regions also known as Celtica (Κελτική in Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

and other Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

sources), Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania ( , ), also known as Aquitaine or Aquitaine Gaul, was a province of the Roman Empire. It lies in present-day southwest France, where it gives its name to the modern region of Aquitaine. It was bordered by the provinces of Gallia ...

, Belgica

Gallia Belgica ("Belgic Gaul") was a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire located in the north-eastern part of Roman Gaul, in what is today primarily northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, along with parts of the Netherlands and German ...

, and Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica (Gaulish: ; br, Arvorig, ) is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and the Loire that includes the Brittany Peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic Coast ...

(Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

). To the Romans, ''Gallia'' was a vast and vague geographical entity distinguished by predominately Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

inhabitants, with "Celticity" a matter of culture as much as speaking ''gallice'' ("in Celtic").

The Latin word ''provincia'' (plural ''provinciae'') originally referred to a task assigned to an official or to a sphere of responsibility within which he was authorized to act, including a military command

A command in military terminology is an organisational unit for which a military commander is responsible. Commands, sometimes called units or formations, form the building blocks of a military. A commander is normally specifically appointed to ...

attached to a specified theater of operations

In warfare, a theater or theatre is an area in which important military events occur or are in progress. A theater can include the entirety of the airspace, land and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations.

T ...

. The assignment of a ''provincia'' defined geographically thus did not always imply annexation of the territory under Roman rule. Provincial administration as such originated in efforts to stabilize an area in the aftermath of war, and only later was the ''provincia'' a formal, pre-existing administrative division regularly assigned to promagistrate

In ancient Rome a promagistrate ( la, pro magistratu) was an ex-consul or ex-praetor whose ''imperium'' (the power to command an army) was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. Thi ...

s. The ''provincia'' of Gaul therefore began as a military command, at first defensive

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indust ...

and later expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

. Independent Gaul was invaded by Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

in the 50s BC and organized under Roman administration by Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

; see Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacient parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century ...

for Gallic provinces in the Imperial era

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

.

Early Republican wars with the Gauls

Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was a battle fought between the Senones – a Gallic tribe led by Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic. The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers, 11 Roman mile ...

and captured Rome are most often identified as Senones

The Senones or Senonii (Gaulish: "the ancient ones") were an ancient Gallic tribe dwelling in the Seine basin, around present-day Sens, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Part of the Senones settled in the Italian peninsula, where they ...

. Over the next hundred years, the Gauls appear in classical sources as allies of the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

and Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they for ...

, but sometimes as invaders. Battles occur on Roman territory and on that held by Etruscans; by Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at leas ...

who later become Roman allies (''socii

The ''socii'' ( in English) or ''foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of ancient Rome, Rome and formed one of the three legal denominations in Roman Italy (''Italia'') along with the Roman citizens (''Cives'') and the ''Latin Rights, Latin ...

'') willingly or under compulsion; and by the Gauls themselves. The defeat of the Senonian stronghold Sena (or ''Senigallia'') in 283 leads to nearly fifty years of mostly peaceful relations between Romans and Celts.

The accounts of these early military conflicts, written by Greek and Roman historians, are complicated by overlays of legend and moralizing. Although stereotypes of impetuous barbarians prevail, among the various historians the Gauls are sometimes portrayed as acting with honour, bravery, or respect, even in the face of Roman treachery. A priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

named Fabius Dorsuo is said to have been allowed by the Gauls to carry out religious rituals during the siege of Rome; three Fabii occasioned outrage on both sides when they abused their responsibilities as ambassadors to the Gauls, and were even accused of having brought about the attack through their actions. Romans cast themselves as underdogs in hand-to-hand combat with physically superior Celts, to such an extent that guile or divine aid is seen as the most likely explanation when a Roman manages to win: T. Manlius earns the nickname (''cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; plural ''cognomina''; from ''con-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became here ...

'') Torquatus

Torquatus, masculine (''torquata'', feminine; ''torquatum'', neuter), is a Latin word meaning "adorned with a neck chain or collar" and may refer to:

People

*Lucius Manlius Torquatus

* Titus Manlius Torquatus (235 BC)

* Silanus

** Marcus Jun ...

by outsmarting a Gaul in single combat and stripping him of his torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

; M. Valerius Corvus got his ''cognomen'' when a divinely-sent raven (''corvus'') distracted his opponent. Regardless of factuality, these stories contributed to the fashioning of a distinctly Roman identity in relation to a Gallic "Other

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

."

As the only foreign enemy to have taken the city, the Gauls represented a "Celtic threat" that loomed large in the Roman imagination for more than 300 years. Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

could still malign Catiline

Lucius Sergius Catilina ( 108 BC – January 62 BC), known in English as Catiline (), was a Roman politician and soldier. He is best known for instigating the Catilinarian conspiracy, a failed attempt to violently seize control of the R ...

in 63 BC with an accusation of plotting the overthrow of the government with the aid of Celtic armed forces. The fear and dread of inferiority engendered by the Gallic sack of Rome became enshrined in Roman foreign policy and myth as a virtually infinite quest to secure an ever-larger periphery; in his war against the Gauls and invasion of Celtic Britain

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ire ...

, Caesar as proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ' ...

could present himself as pursuing the old grudge to what Romans saw as literally the end of the world.

''Dictatores'' and Celtic Italy

The following table shows Early Republican military commanders against the Gauls on the Italian peninsula. These men were granted ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from ''auctoritas'' and ''potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic an ...

'' as consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vario ...

s, the highest elected offices in Roman government, and also as '' dictatores''. The dictatorship most likely originated as a military office; both Cicero and Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

thought that its purpose was to ensure strategic oversight and unified command in wartime — the ''dictator'' is he who gives the word (''dictum''). The Roman custom that a commander had to lay down arms outside the city limits (''pomerium

The ''pomerium'' or ''pomoerium'' was a religious boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its ''pomerium''; everything beyond it was simply territory (''ager'') belonging to Rome.

...

'') before entering also suggests how the powers of the ''dictator'' originally might have been restricted within the civil realm; he could not, for instance, override the people's tribunes. The ''dictator'' was nominated by a consul, not elected, and he was expected to step aside when the job was done, with a limit of six months considered standard. In contrast to the annual magistracies set by the religio-astronomical calendar, this six-month term coincides with the usual length of the military campaigning season, given its seasonality in antiquity. In 332 ''(see table)'', for instance, a ''dictator'' was nominated specifically in anticipation of a Gallic war, which in the event never materialized. In 360, a ''dictator'' had been named to quell the Celtic crisis ''(Gallicus tumultus)''; one of the consuls that year had the specific task (''provincia'') of dealing with the Gallic alliance based in Tibur (modern-day Tivoli). Both commanders succeeded in their missions, but only the constitutionally elected consul was granted the honour of a triumph

The Roman triumph (Latin triumphus) was a celebration for a victorious military commander in ancient Rome. For later imitations, in life or in art, see Trionfo. Numerous later uses of the term, up to the present, are derived directly or indirectl ...

. The ''dictatores'' continued most often to have a military role into the Middle Republic, but when Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had ...

revived the office in the late 80s, it had fallen into disuse for more than a century, in part because a system had developed for assigning provincial commands with administrative oversight as a result of permanent annexations of territories.

Table of commanders in Italo-Gallic wars

Annexing Cisalpine Gaul

The Roman takeover of Cisalpine Gaul, or "Gaul on this side of the

The Roman takeover of Cisalpine Gaul, or "Gaul on this side of the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

," was a gradual process of long duration. "It was in Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, in the Celtic lands of the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

, and in Venetia and Histria," notes Fergus Millar

Sir Fergus Graham Burtholme Millar, (; 5 July 1935 – 15 July 2019) was a British ancient historian and academic. He was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford between 1984 and 2002. He numbers among the most influ ...

in his classic essay "The Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic, 200–151 B.C.," "that the Romans of this period exhibited a consistent and unremitting combination of imperialism, militarism, expansionism, and colonialism." Although sources for much of the period are sketchy, with the exception of Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, it becomes nearly impossible to argue that Rome acted only defensively: "Rome's wars in the north of the Italian peninsula" — not only against the Gauls, but the Etruscans and the Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at leas ...

— "were largely of her own devising." Provincial assignments and military actions involving Liguria, Venetia, and Istria (Histria) are included in the table below when related directly to Gaul.

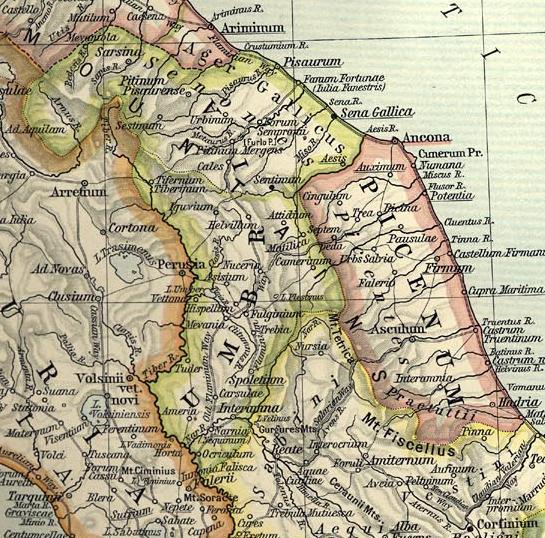

The ''Ager Gallicus''

The defeat of the Senones and Boii in the late 280s had brought the occupation of the ''Ager Gallicus

The expression Ager Gallicus defines the territory of the Senone Gauls after it was devastated and conquered by Rome in 284 BC or 283 BC, either after the Battle of Arretium or the Battle of Lake Vadimon.

Destruction of the Ager Gallicus

Accord ...

'' along the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

and the establishment of the first Roman colony in previously Gallic territory. The ''ager Gallicus'', formerly in the possession of the Senones, was the land between Ariminum

Rimini ( , ; rgn, Rémin; la, Ariminum) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy and capital city of the Province of Rimini. It sprawls along the Adriatic Sea, on the coast between the rivers Marecchia (the ancient ''Ariminus ...

and Picenum

Picenum was a region of ancient Italy. The name is an exonym assigned by the Romans, who conquered and incorporated it into the Roman Republic. Picenum was ''Regio V'' in the Augustan territorial organization of Roman Italy. Picenum was also ...

, and was the first territory acquired by Rome in Cispadane Gaul.

Since that time, good relations between Rome and its Gallic neighbors had extended into a fifth decade. Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

says that the ''lex Flaminia agraria'' of 232, which provided for the distribution of land in the ''Ager Gallicus'' to Roman citizens, threatened the existing peace with Gauls such as the Boii who bordered the ''ager''. Ostensibly, this land had been ''ager publicus

The ''ager publicus'' (; "public land") is the Latin name for the public land of Ancient Rome. It was usually acquired via the means of expropriation from enemies of Rome.

History

In the earliest periods of Roman expansion in central Italy, th ...

'', that is, owned by the public; in practice, it was exploited for the benefit of the senatorial elite, who objected vehemently to the redistribution program.

The first Roman colonies

Colonies in antiquity were post-Iron Age city-states founded from a mother-city (its "metropolis"), not from a territory-at-large. Bonds between a colony and its metropolis remained often close, and took specific forms during the period of classic ...

in northern Italy were established in 218, but not until the end of the 2nd century could the Romans claim firm control of the region all the way to the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

. After a series of decisive victories against Gauls and Ligurians in 200, ''provinciae'' pertaining to the Gauls take on an increasingly diplomatic and administrative character.

The province of Cisalpina at first was one of the military commands that might be assigned to the two consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and six praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vario ...

s before the territory had been annexed. A military command (''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from ''auctoritas'' and ''potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic an ...

'') was sometimes extended past a magistrate's one-year term of elected office for a year or two (see ''prorogatio

''Prorogatio'' was a Roman practice in which a Roman magistrate's duties were extended beyond its normal annual term. It developed as a response to Roman expansion's demands for more generals and governors to administer conquered territories.

Pr ...

''); this prorogation allowed Rome to maintain continuity in ongoing military operations under experienced officers while still controlling and limiting the number of individuals authorized to hold command.

After major military operations had ceased, the commander's abilities as an administrator were put to the test. In the absence of an ideal leader who was both a bold and experienced general and a masterful diplomat and meticulous administrator, provincial governorships were liable to exploitive practices of self-enrichment that damaged the legitimacy of Roman rule. Governed peoples had recourse through Roman courts for unjust acts committed against them by their governors, but because the case had to be presented by a Roman citizen

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

, usually a '' patronus'' with a family history of relations to the offended parties, these prosecutions were almost always politicized. As the number of citizens in a province increased, so too their connections to powerful families in Rome and the network of mutual obligations from which they could expect to benefit.

By the late Republic, Cisalpina of all the Roman provinces had the greatest number of citizens in its population; although the difficulties of travel might stand in the way of participating in Roman elections

Elections in the Roman Republic were an essential part of its governance, with participation only being afforded to Roman citizens. Upper-class interests, centered in the urban political environment of cities, often trumped the concerns of the div ...

, northern Italy offered significant blocs of voters for Romans who cultivated their clients well. Popularist politicians in particular were associated with the cause of extending citizenship to the disenfranchised, and were accused by the conservative oligarchs of doing so merely to build loyalty and acquire votes. Toward the end of the Social War in 89, all free men in Cisalpine Gaul south of the Po River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ligurian language (ancient), Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira (river), Mair ...

(Latin ''Padus'') — that is, Cispadane Gaul, "Gaul on this side of the Po" — had become entitled to Roman citizenship.

Many Transpadanes, or residents of Cisalpina north of the Po, were Romans or held Latin right

Latin rights (also Latin citizenship, Latin: ''ius Latii'' or ''ius latinum'') were a set of legal rights that were originally granted to the Latins (Latin: "Latini", the People of Latium, the land of the Latins) under Roman law in their origin ...

s, but the issue of blanket citizenship was not fully resolved until 49, with the passage of a law by Caesar. After 42 BC, Cisalpina was so thoroughly incorporated into the Roman system of government that it was no longer assigned as a province; the region was administered directly from Rome and by the same forms of municipal government

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

as the rest of the Italian peninsula.

In Latin sources before ''ca.'' 100 BC, ''Gallia'' is a flexible word that refers often to Cisalpine Gaul alone, but sometimes to Gaul as an indefinite totality and sometimes in a very limited sense to only Cispadane Gaul. The following table lists consuls, praetors and promagistrate

In ancient Rome a promagistrate ( la, pro magistratu) was an ex-consul or ex-praetor whose ''imperium'' (the power to command an army) was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. Thi ...

s — no ''dictatores'' are recorded against the Gauls — assigned to ''Gallia'' until 125 BC, when the administration of Cisalpina should be considered in light of actions in Transalpine Gaul. After 197 BC, commanders of praetorian rank are no longer assigned to Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

or against the Gauls; military operations in northern Italy are usually conducted by both consuls during this period, or one consul if another war was being waged abroad.

Table of Gallic ''provinciae'' through 126 BC

Transalpine Gaul

''Gallia Transalpina'' at first could refer broadly to "Gaul on the other side of the Alps," but after the conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the 120s BC came to specify the Roman province in the south (''Provincia nostra'', "our Province," hence

''Gallia Transalpina'' at first could refer broadly to "Gaul on the other side of the Alps," but after the conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the 120s BC came to specify the Roman province in the south (''Provincia nostra'', "our Province," hence Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

). Because the term ''Transalpina'' had a history of usage in the more general sense, the province was often called the Narbonensis, after the colonial headquarters in Narbonne. The establishment of the Transalpine province is usually dated to the military victories of Domitius Ahenobarbus and Quintus Fabius Maximus over the Arverni

The Arverni (Gaulish: *''Aruernoi'') were a Gallic people dwelling in the modern Auvergne region during the Iron Age and the Roman period. They were one of the most powerful tribes of ancient Gaul, contesting primacy over the region with the ne ...

and Allobroges

The Allobroges (Gaulish: *''Allobrogis'', 'foreigner, exiled'; grc, Ἀλλοβρίγων, Ἀλλόβριγες) were a Gallic people dwelling in a large territory between the Rhône river and the Alps during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

...

in the 120s, and the refounding of Narbo as a Roman colony

A Roman (plural ) was originally a Roman outpost established in conquered territory to secure it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term ''colony''.

Characteri ...

in 118 BC. Evidence is scant, however, that Transalpina was assigned as a province over the next 15 years, until the Cimbrian invasions compelled the Romans to take action. There may have been no regular administration until after the victories of Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbric and Jugurthine wars, he held the office of consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his important refor ...

in 101 BC. The historical record of Transalpine promagistracies continues to be sketchy until the 60s, with a few exceptions such as Valerius Flaccus's tenure ''ca.'' 85–81 BC, one of the longest known Gallic governorships.

During the Republic, the provinces of Cisalpina and Transalpina were governed sometimes jointly, sometimes separately; Caesar was allotted both provinces, and in his first five-year term divided his time between military campaigns in Transalpina and administrative duties in Cisalpina during the winter months. One factor in the Roman drive to control southern Gaul had been the desire for a secure land route to the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

(''Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

''), where the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BCE. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strab ...

(''Celtiberi'') also spoke a form of Celtic or a language closely related to it, with at least some cultural similarities to the other Celts. Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

and Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a region of Hispania during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of modern Spain and extending to all of Lusitania (m ...

had been administered as provinces since 197 BC as a result of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

, which also had ignited the first direct if postponed Roman interest in southern Gaul; the first Roman colonies had also been established in Cisalpine Gaul during this time.

In the table following, when a governor is listed for Cisalpina only, he may also have governed Transalpina in the absence of another known official, and vice versa; at times, however, Hispania Citerior and Transalpina were governed jointly instead. Political and military factors determined whether and how these provincial assignments were combined, including shifting alliances among those governed, strategic considerations during the Social Wars and Roman civil wars

This is a list of civil wars and organized civil disorder, revolts and rebellions in ancient Rome (Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, and Roman Empire) until the fall of the Western Roman Empire (753 BCE – 476 CE). For the Eastern Roman Empire or ...

, the availability of experienced administrators and commanders, and jockeying to maintain a balance of power among Roman oligarchs. Following the civil wars of the 40s, ''Narbonensis'' seems to refer specifically to the established province in southern Gaul, while ''Transalpina'' may include new territories claimed through Caesar's military campaigns in formerly independent Celtica and formally organized later by Augustus.

Table of Gallic governors 125–42 BC

Triumviral years

In the tumultuous period following Caesar's death, during the ascendancy of theSecond Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created for Mark Antony, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November 43 BC with a ...

, Gaul was acted upon by various commanders, until M. Vipsanius Agrippa arrived as proconsul in 39 to quell unrest. Scholars have paid relatively scant attention to the question of why Gaul failed to take advantage of Rome's disarray during the civil wars of the 40s and 30s to revolt ''in toto''; it is sometimes assumed that the population was too decimated to take a stand, but the numbers in so far as they are known make this unlikely. In 57, for instance, Caesar had reported that the Nervii

The Nervii were one of the most powerful Belgic tribes of northern Gaul at the time of its conquest by Rome. Their territory corresponds to the central part of modern Belgium, including Brussels, and stretched southwards into French Hainault. D ...

had 50,000 men of fighting age; he supposed that only 500 survived the Battle of the Sabis

The Battle of the Sabis, also (arguably erroneously) known as the Battle of the Sambre or the Battle against the Nervians (or Nervii), was fought in 57 BC near modern Saulzoir in Northern France, between Caesar's Roman legion, legions and an asso ...

, but five years later they were able to provide a force of 5,000 men. Although the figures may be unreliable in the absolute, they indicate the resilience of the population. In 52, after the surrender of the pan-Gallic army at Alesia, Caesar had granted amnesty to the armies of both the Arverni

The Arverni (Gaulish: *''Aruernoi'') were a Gallic people dwelling in the modern Auvergne region during the Iron Age and the Roman period. They were one of the most powerful tribes of ancient Gaul, contesting primacy over the region with the ne ...

and Aedui

The Aedui or Haedui (Gaulish: *''Aiduoi'', 'the Ardent'; grc, Aἴδουοι) were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the modern Burgundy region during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

The Aedui had an ambiguous relationship with the Roman Republic ...

, each of which he estimated at 30,000 men, and sent them home. After the failure of Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix (; Greek: Οὐερκιγγετόριξ; – 46 BC) was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. Despite h ...

's strategy of massing allied forces, the surviving Gallic leaders had continued to wage a guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

with some success and hope of attrition, until Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

) came to an arrangement with the last Celtic king known to retain his independence, Commius

Commius (Commios, Comius, Comnios) was a king of the Belgic nation of the Atrebates, initially in Gaul, then in Britain, in the 1st century BC.

Ally of Caesar

When Julius Caesar conquered the Atrebates in Gaul in 57 BC, as recounted in his '' ...

of the Atrebates

The Atrebates (Gaulish: *''Atrebatis'', 'dwellers, land-owners, possessors of the soil') were a Belgic tribe of the Iron Age and the Roman period, originally dwelling in the Artois region.

After the tribes of Gallia Belgica were defeated by Caes ...

, who had led the relief forces at Alesia. Over the course of the following two decades, Gallic losses in the 50s would have been replaced by the maturation of the male population, while available Roman forces were largely occupied by fighting each other. The Gauls may have imagined that the Romans would weaken themselves in civil war to such an extent that a rebellion was moot or not worth the trouble; Caesar reports that the Gauls kept themselves informed about political events in Rome that might affect them.

In 44 BC, Antony was the proconsul assigned to both Cisalpina and Transalpina; his ability to come to an understanding with the Gauls, as demonstrated by his arrangements with Commius, is further indicated by the willingness of a Sequani

The Sequani were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the upper river basin of the Arar river (Saône), the valley of the Doubs and the Jura Mountains during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Sequanos'' by Caesar (mid-1s ...

an leader to execute Decimus Brutus at his behest. This Brutus had served in Gaul under Caesar from 56 (or earlier). Although his experience in Gallic relations exceeded that of his peer Antony, whose earliest appearance in Caesar's account of the war is around the time of the Battle of Alesia, Celtic antipathy may have been spurred by Brutus's betrayal of Caesar, given the high value Celts placed on loyalty to their sworn leaders.

Broughton lists no Gallic governors after Agrippa through 31, the year with which ''The Magistrates of the Roman Republic'' concludes. Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

began to reorganize Transalpine Gaul with its newly conquered territories into administrative regions in 27 BC.Woolf, ''Becoming Roman'', p. 39.

Selected bibliography

*A.L.F. Rivet, ''Gallia Narbonensis: Southern France in Roman Times'' (London, 1988) * Charles Ebel, ''Transalpine Gaul: The Emergence of a Roman Province'' (Brill, 1976) * T. Corey Brennan, ''The Praetorship in the Roman Republic'' (Oxford University Press, 2000) *Andrew Lintott

Andrew William Lintott (born 9 December 1936) is a British classical scholar who specialises in the political and administrative history of ancient Rome, Roman law and epigraphy. He is an emeritus fellow of Worcester College, University of Oxford ...

, ''The Constitution of the Roman Republic'' (Oxford University Press, 1999)

* Unless otherwise noted, the sources for promagistracies in Gaul and their dates is T.R.S. Broughton

Thomas Robert Shannon Broughton, FBA (; 17 February 1900 – 17 September 1993) was a Canadian classical scholar and leading Latin prosopographer of the twentieth century. He is especially noted for his definitive three-volume work, '' Magistr ...

, ''The Magistrates of the Roman Republic'' (New York: American Philological Association, 1951, 1986), vols. 1–3, abbreviated ''MRR1'', ''MRR2'' and ''MRR3''.

References

{{Roman Governors Roman Republic Roman governors of Gaul Lists of office-holders in ancient RomeGaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...