Roman Herzog on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

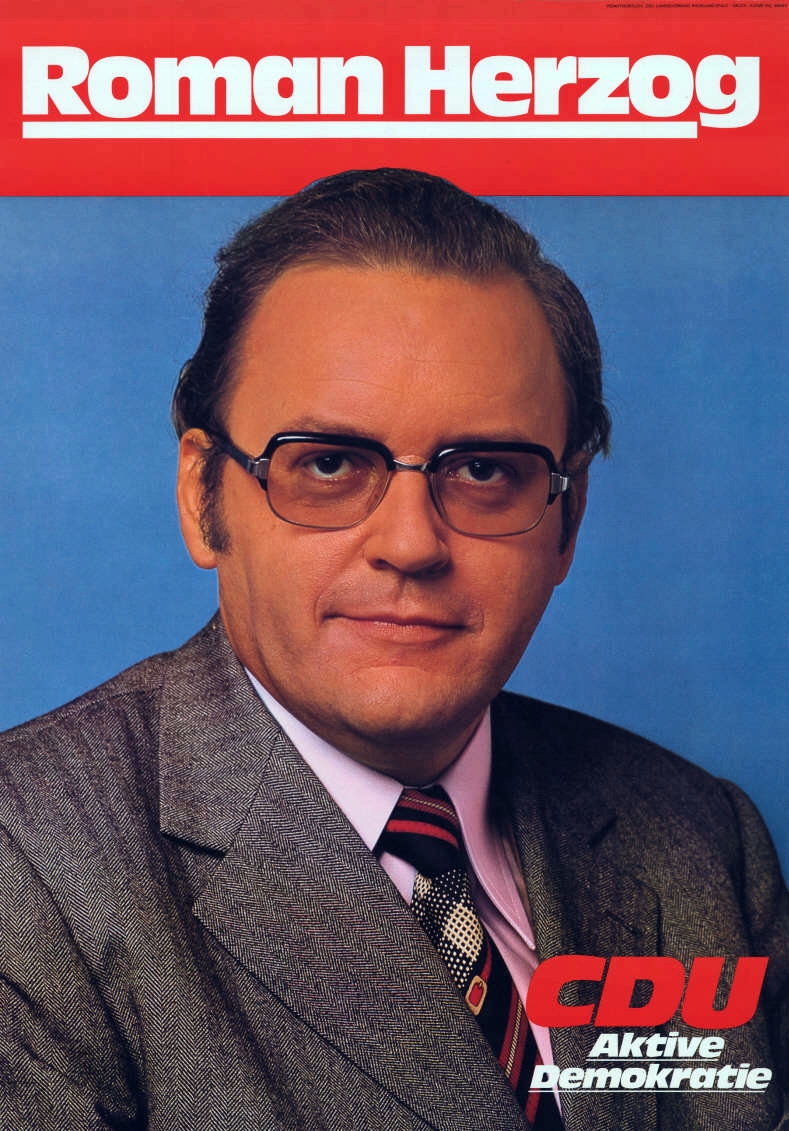

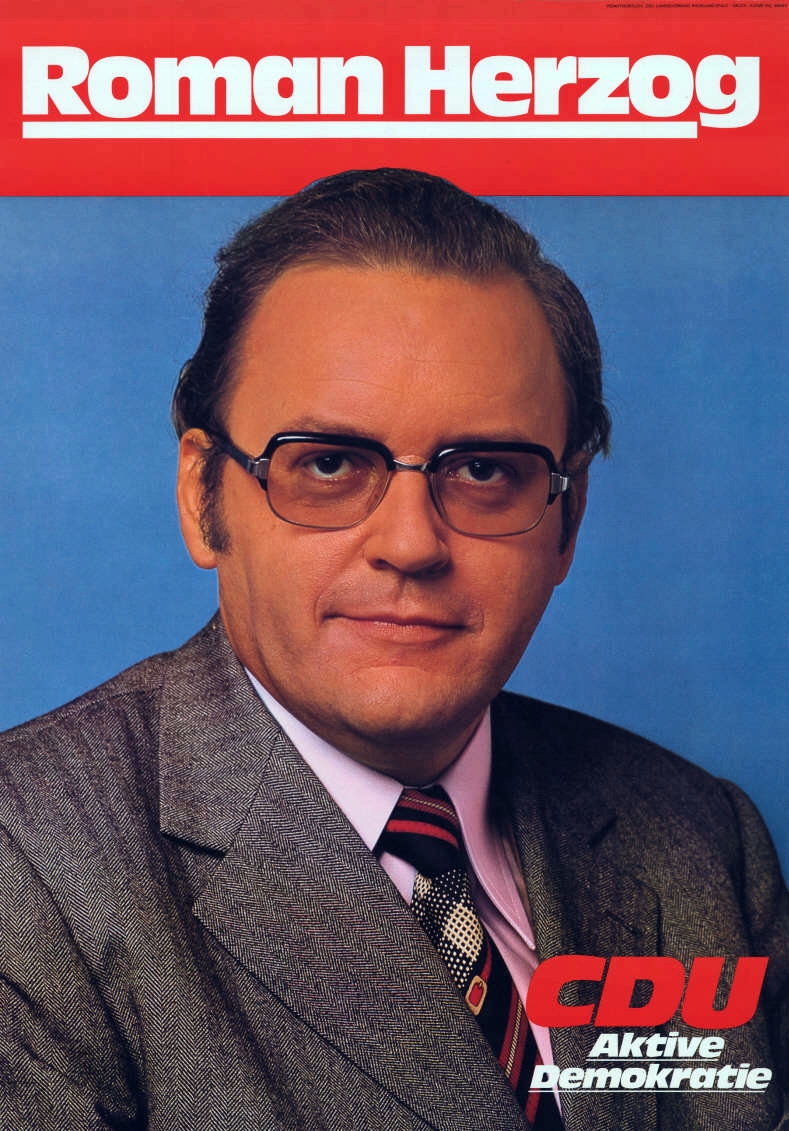

Roman Herzog (; 5 April 1934 – 10 January 2017) was a German politician, judge and legal scholar, who served as the

Herzog's political career began in 1973, as a representative of the state (''Land'') of

Herzog's political career began in 1973, as a representative of the state (''Land'') of

German Coalition Is Divided Over Kohl's Choice for President

''

Kohl's Choice Is Named German President

''

president of Germany

The president of Germany, officially the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: link=no, Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland),The official title within Germany is ', with ' being added in international corres ...

from 1994 to 1999. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), he was the first president to be elected after the reunification of Germany

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

. He previously served as a judge of the Federal Constitutional Court

The Federal Constitutional Court (german: link=no, Bundesverfassungsgericht ; abbreviated: ) is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law () of Germany. Since its inc ...

, and he was the President of the court 1987–1994. Before his appointment as a judge he was a professor of law. He received the 1997 Charlemagne Prize

The Charlemagne Prize (german: Karlspreis; full name originally ''Internationaler Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen'', International Charlemagne Prize of the City of Aachen, since 1988 ''Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen'', International Charlemagn ...

.

Early life and academic career

Roman Herzog was born inLandshut

Landshut (; bar, Landshuad) is a town in Bavaria in the south-east of Germany. Situated on the banks of the River Isar, Landshut is the capital of Lower Bavaria, one of the seven administrative regions of the Free State of Bavaria. It is also t ...

, Bavaria, Germany, in 1934 to a Protestant family. His father was an archivist. He studied law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

in Munich and passed his state law examination. He completed his doctoral studies in 1958 with a dissertation on Basic Law and the European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by t ...

.

He worked as an assistant at the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It is Germany's List of universities in Germany, sixth-oldest u ...

until 1964, where he also passed his second juristic state exam. For his paper ''Die Wesensmerkmale der Staatsorganisation in rechtlicher und entwicklungsgeschichtlicher Sicht'' ("Characteristics of state organization from a juristic and developmental-historical viewpoint"), he was awarded the title of professor in 1964, and taught at the University of Munich until 1966. He then taught constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a State (polity), state, namely, the executive (government), executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as th ...

and political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

as a full professor at the Free University of Berlin

The Free University of Berlin (, often abbreviated as FU Berlin or simply FU) is a public research university in Berlin, Germany. It is consistently ranked among Germany's best universities, with particular strengths in political science and t ...

. It was during this period that he coedited a commentary of the Basic Law. In 1969, he accepted a chair of public law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a state, between different branches of governments, as well as relationships between persons that are of direct ...

at the German University of Administrative Sciences in Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ''Speier'', French: ''Spire,'' historical English: ''Spires''; pfl, Schbaija) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the river Rhine, Speyer li ...

, serving as university president in 1971–72.

Political career

Herzog's political career began in 1973, as a representative of the state (''Land'') of

Herzog's political career began in 1973, as a representative of the state (''Land'') of Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

in the Federal government in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr r ...

. He served as State Minister for Culture and Sports in the Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

State Government led by Minister-President

A minister-president or minister president is the head of government in a number of European countries or subnational governments with a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government where they preside over the council of ministers. It ...

Lothar Späth

Lothar Späth (16 November 1937 – 18 March 2016) was a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (Germany), CDU.

Life

Späth was born in Sigmaringen.

From 30 August 1978 to 13 January 1991 Späth was the 5th Minister President of ...

from 1978. In 1980 he was elected to the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg

The Landtag of Baden-Württemberg is the diet of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It convenes in Stuttgart and currently consists of 154 members of five political parties. The majority before the 2021 election was a coalition of the All ...

and took over the State Ministry of the Interior.Werner Filmer, Heribert Schwan: ''Roman Herzog – Die Biographie''. Goldmann, Munich 1996, . As the regional interior minister, he attracted attention when he imposed a levy on nonapproved demonstrations and his proposal for the police to be equipped with rubber-bullet guns.

Herzog was long active in the Evangelical Church in Germany

The Evangelical Church in Germany (german: Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, abbreviated EKD) is a federation of twenty Lutheranism, Lutheran, Continental Reformed church, Reformed (Calvinism, Calvinist) and united and uniting churches, United ( ...

. Until 1980, he was head of the Chamber for Public Responsibility of this church, and, beginning in 1982, he was a member of the synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

. In 1983 Herzog was elected a judge at the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany

The Federal Constitutional Court (german: link=no, Bundesverfassungsgericht ; abbreviated: ) is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law () of Germany. Since its in ...

(''Bundesverfassungsgericht'') in Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the third-largest city of the German state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital of Stuttgart and Mannheim, and the 22nd-largest city in the nation, with 308,436 inhabitants. ...

, replacing Ernst Benda

Ernst Benda (15 January 1925 – 2 March 2009) was a German legal scholar, politician and judge. He served as the fourth president of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany from 1971 to 1983. Benda briefly served as Minister of the Interior ...

. From 1987 until 1994, he also served as the president of the Court, this time replacing Wolfgang Zeidler. In September 1994, he was succeeded in that office by Jutta Limbach

Jutta Limbach (27 March 1934 – 10 September 2016) was a German jurist and politician. She was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and served as President of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany from 1994 to 2002, th ...

.

President of Germany, 1994–1999

Already in 1993, ChancellorHelmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longes ...

had selected Herzog as candidate for the 1994 presidential election, after his previous choice, the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

State Minister of Justice, Steffen Heitmann Steffen Heitmann (born September 8, 1944, in Dresden) is a German Protestant theologian, church jurist and former politician. From 1990 to 2000 he was Minister of Justice of Saxony, and was a member of the Saxon Landtag from 1994 to 2009. From 1991 ...

, had to withdraw because of an uproar about statements he made on the German past, ethnic conflict and the role of women.Craig R. Whitney (1 May 1994)German Coalition Is Divided Over Kohl's Choice for President

''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. By early 1994, however, leaders of the Free Democrats, the junior members of Kohl's coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

, expressed support for Johannes Rau

Johannes Rau (; 16 January 193127 January 2006) was a German politician (SPD). He was the president of Germany from 1 July 1999 until 30 June 2004 and the minister president of North Rhine-Westphalia from 20 September 1978 to 9 June 1998. In the ...

, the candidate whom the opposition Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

nominated. German media also speculated that other potential candidates included Kurt Masur

Kurt Masur (18 July 1927 – 19 December 2015) was a German conductor. Called "one of the last old-style maestros", he directed many of the principal orchestras of his era. He had a long career as the Kapellmeister of the Leipzig Gewandhaus O ...

and Walther Leisler Kiep

Walther Gottlieb Louis Leisler Kiep (5 January 1926 – 9 May 2016) was a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). He was a member of the Bundestag between 1965 and 1976 and again from 1980 to 1982. After switching to state-le ...

. The former Foreign Minister, Hans Dietrich Genscher

Hans-Dietrich Genscher (21 March 1927 – 31 March 2016) was a German statesman and a member of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), who served as Federal Minister of the Interior from 1969 to 1974, and as Federal Minister for Foreign Affa ...

refused to run.

Herzog was elected President of Germany by the Federal Assembly ( Bundesversammlung) on 23 May 1994. In the decisive third round of voting, he won the support of the Free Democrats.Stephen Kinzer

Stephen Kinzer (born August 4, 1951) is an American author, journalist, and academic. A former ''New York Times'' correspondent, he has published several books, and writes for several newspapers and news agencies.

Reporting career

During the 198 ...

(24 May 1994)Kohl's Choice Is Named German President

''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. Their decision was taken as a sign that the coalition remained firm.

Herzog took office as Federal President on 1 July 1994. He participated in the commemorations of the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occ ...

during the Nazi occupation of Poland

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

in 1994. In a widely commended speech, he paid tribute to the Polish fighters and people and asked Poles for "forgiveness for what has been done to you by the Germans". In the speech, he strongly emphasized the enormity of anguish the Polish people suffered through Nazi Germany but he also made an indirect reference to the sufferings that the Germans experienced in World War II.

In 1995, Herzog was one of the few foreign dignitaries taking part in the observances on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

who chose to attend a Jewish service at the site of the camp rather than the official opening ceremony in Cracow sponsored by the Polish Government. In January 1996, Herzog declared 27 January, the anniversary of the 1945 liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, as Germany's official day of remembrance for the victims of Hitler's regime. in late 1997, in a major step for Germany officially recognizing the murder and suffering of the Roma and Sinti under the Nazis, he said that the persecution of the Roma and Sinti was the same as the terror against the Jews.

In April 1997, Herzog caused a nationwide controversy when, in a speech given at the Hotel Adlon

The Hotel Adlon Kempinski Berlin is a luxury hotel in Berlin, Germany. It is on Unter den Linden, the main boulevard in the central Mitte district, at the corner with Pariser Platz, directly opposite the Brandenburg Gate.

The original Hotel Adlon ...

in Berlin, he portrayed Germany as dangerously delaying social and economic changes. In the speech, he rebuked leaders for legislative gridlock and decried a sense of national "dejection," a "feeling of paralysis" and even an "unbelievable mental depression." Compared with what he called the more innovative economies of Asia and America, he said that Germany was "threatened with falling behind."

In November 1998, Herzog's office

An office is a space where an Organization, organization's employees perform Business administration, administrative Work (human activity), work in order to support and realize objects and Goals, plans, action theory, goals of the organizati ...

formally moved to Berlin, becoming the first federal agency to shift from Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr r ...

to the redesignated capital city. He retained his position until 30 June 1999 and did not seek reelection. At the end of his five-year term as head of state, he was succeeded by Johannes Rau

Johannes Rau (; 16 January 193127 January 2006) was a German politician (SPD). He was the president of Germany from 1 July 1999 until 30 June 2004 and the minister president of North Rhine-Westphalia from 20 September 1978 to 9 June 1998. In the ...

.

Post-presidency

From December 1999 to October 2000, Herzog chaired theEuropean Convention Several bodies or treaties are known as European Convention.

Bodies of the European Union

* European Convention (1999–2000) which drafted the:

** ''Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union'' (2000 / 2009)

* Convention on the Future of ...

which drafted the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrines certain political, social, and economic rights for European Union (EU) citizens and residents into EU law. It was drafted by the European Convention and solemnly proclaim ...

. In January–March 2000, with former central bank President Hans Tietmeyer

Hans Tietmeyer (18 August 1931 – 27 December 2016) was a German economist and regarded as one of the foremost experts on international financial matters. He was president of Deutsche Bundesbank from 1993 until 1999 and remained afterwards one o ...

and former federal judge Paul Kirchhof

Paul Kirchhof (born February 21, 1943 in Osnabrück) is a German jurist and tax law expert. He is also a professor of law, member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and, a former judge in the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (' ...

, Herzog led an independent commission to investigate a financing scandal affecting the CDU. Amid a German debate over the ethics of research in biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

and in particular the use of embryos for genetic inquiry and diagnosis, Herzog argued in 2001 that an absolute ban on research on embryonic stem cells

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre- implantation embryo. Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist ...

– which have the ability to develop into the body's different tissues – would be excessive, stating: "I am not prepared to explain to a child sick with cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare genetic disorder that affects mostly the lungs, but also the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and intestine. Long-term issues include difficulty breathing and coughing up mucus as a result of frequent lung infections. O ...

, facing death and fighting for breath, the ethical grounds that hinder the science which could save him".

In response to Chancellor Gerhard Schröder

Gerhard Fritz Kurt "Gerd" Schröder (; born 7 April 1944) is a German lobbyist and former politician, who served as the chancellor of Germany from 1998 to 2005. From 1999 to 2004, he was also the Leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germa ...

's "Agenda 2010

The Agenda 2010 is a series of reforms planned and executed by the German government in the early 2000s, a Social-Democrats/ Greens coalition at that time, which aimed to reform the German welfare system and labour relations. The declared objecti ...

" presented in 2003, the then-opposition leader and CDU chair Angela Merkel

Angela Dorothea Merkel (; ; born 17 July 1954) is a German former politician and scientist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she previously served as Leader of the Oppo ...

assigned the task of drafting alternative proposals for social welfare reform to a commission led by Herzog. The party later approved the Herzog Commission's package of reform proposals, whose recommendations included decoupling health and nursing care premiums from people's earnings and levying a lump monthly sum across the board instead.

Herzog died in the early hours of 10 January 2017 at the age of 82.

Other activities (selection)

*Friedrich-August-von-Hayek-Stiftung The Friedrich-August-von-Hayek-Stiftung was founded in May 1999 to mark the 100th birthday of the Nobel Prize winner Friedrich August von Hayek. The foundation has its seat in Freiburg im Breisgau (South Germany) and is run by Dr. habil Lüder Gerk ...

, Chairman of the Board of Trustees (1999–2013)

* Hertie-Stiftung, Honorary Chairman of the Board of Trustees

* Konrad Adenauer Foundation

The Konrad Adenauer Foundation (german: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, KAS) is a German political party foundation associated with but independent of the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU). The foundation's headquarters are located in Sank ...

, Chairman of the Board of Trustees

* Stiftung Brandenburger Tor, Chairman of the Board of Trustees

* AAFortuna, Member of the Supervisory Board

* Bucerius Law School, Member of the Founding Commission

* Dresden Frauenkirche

The Dresden Frauenkirche (german: Dresdner Frauenkirche, , ''Church of Our Lady'') is a Evangelical Church in Germany, Lutheran church in Dresden, the capital of the German state of Saxony. Destroyed during the Allied Bombing of Dresden in Wo ...

, Member of the Board of Trustees

* German Cancer Research Center

The German Cancer Research Center (known as the Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum or simply DKFZ in German) is a national cancer research center based in Heidelberg, Germany. It is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres, ...

(DKFZ), Member of the Advisory Board

* Hartz, Regehr & Partner, Member of the Advisory Board

* Phi Delta Phi

Phi Delta Phi () is an international legal honor society and the oldest legal organization in continuous existence in the United States. Phi Delta Phi was originally a professional fraternity but became an honor society in 2012.

The fraternity ...

– Richard von Weizsäcker

Richard Karl Freiherr von Weizsäcker (; 15 April 1920 – 31 January 2015) was a German politician ( CDU), who served as President of Germany from 1984 to 1994. Born into the aristocratic Weizsäcker family, who were part of the German nobilit ...

Inn Tübingen, Honorary Member

* 2006 FIFA World Cup Organizing Committee, Member of the Board of Trustees (2005–2006)

* Technische Universität München

The Technical University of Munich (TUM or TU Munich; german: Technische Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It specializes in engineering, technology, medicine, and applied and natural sciences.

Establis ...

, Member of the University Council (1999–2005)

* ZEIT-Stiftung

The charitable foundation ''Zeit-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius'' (house style: ZEIT-Stiftung) is registered in Hamburg. Its aim is to fund projects in research and scholarship, arts and culture, as well as education and training. It was fou ...

, Member of the Board of Trustees (1999–2008)

Recognition (selection)

* 1994: Grand Cross of the White Rose of Finland with Collar * 1996: Honorary Doctorate of theUniversity of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

* 1997: Charlemagne Prize

The Charlemagne Prize (german: Karlspreis; full name originally ''Internationaler Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen'', International Charlemagne Prize of the City of Aachen, since 1988 ''Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen'', International Charlemagn ...

of the City of Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

* 1997: Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria

The Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria (german: Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um die Republik Österreich) is a state decoration of the Republic of Austria. It is divided into 15 classes and is the highest award in the A ...

* 1997: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

The Order of Merit of the Italian Republic ( it, Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana) is the senior Italian order of merit. It was established in 1951 by the second President of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi.

The highest-ranking ...

* 1997: Knight of the Collar of the Spanish Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Order of Isabella the Catholic ( es, Orden de Isabel la Católica) is a Spanish civil order and honor granted to persons and institutions in recognition of extraordinary services to the homeland or the promotion of international relations a ...

* 1997: Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (Malaysia)

* 1998: Honorary Doctorate of the University of Wrocław

, ''Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau'' (before 1945)

, free_label = Specialty programs

, free =

, colors = Blue

, website uni.wroc.pl

The University of Wrocław ( pl, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, U ...

* 1998: Honorary Citizenship of the City of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

* 1998: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

* 1999: Honorary Citizenship of the City of Landshut

Landshut (; bar, Landshuad) is a town in Bavaria in the south-east of Germany. Situated on the banks of the River Isar, Landshut is the capital of Lower Bavaria, one of the seven administrative regions of the Free State of Bavaria. It is also t ...

* 1999: Commander Grand Cross of the Latvian Order of the Three Stars

Order of the Three Stars ( lv, Triju Zvaigžņu ordenis) is the highest civilian order awarded for meritorious service to Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvija ...

* 2000: Toleranzpreis der Evangelischen Akademie Tutzing The Toleranzpreis der Evangelischen Akademie Tutzing (Prize for tolerance) is a prize that has been awarded biennially by the Evangelische Akademie Tutzing to personalities who have been influential towards a dialogue between cultures and religions. ...

* 2002: Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg

Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg (german: link=no, Verdienstorden des Landes Baden-Württemberg) is the highest award of the German State of Baden-Württemberg. Established 26 November 1974, it was originally called the Medal of Merit of Bad ...

* 2003: Gustav Adolf Prize

*2003: Franz-Josef-Strauß-Preis

* 2006: Max Friedlaender Prize

* 2010: Lennart Bernadotte Medal of the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings

The Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings are annual scientific conferences held in Lindau, Bavaria, Germany, since 1951. Their aim is to bring together Nobel laureates and young scientists to foster scientific exchange between different generations, ...

*2012: European Craftmanship Award

*2015: Honorary prize of Friedrich-August-von-Hayek-Stiftung The Friedrich-August-von-Hayek-Stiftung was founded in May 1999 to mark the 100th birthday of the Nobel Prize winner Friedrich August von Hayek. The foundation has its seat in Freiburg im Breisgau (South Germany) and is run by Dr. habil Lüder Gerk ...

Personal life and death

Herzog's wife, Christiane Herzog, died on 19 June 2000. In 2001, he married Alexandra Freifrau von Berlichingen. He was a member of theEvangelical Church in Germany

The Evangelical Church in Germany (german: Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, abbreviated EKD) is a federation of twenty Lutheranism, Lutheran, Continental Reformed church, Reformed (Calvinism, Calvinist) and united and uniting churches, United ( ...

. He died on 10 January 2017 at the age of 82.

References

Literature

*Kai Diekmann, Ulrich Reitz, Wolfgang Stock: ''Roman Herzog – Der neue Bundespräsident im Gespräch''. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1994, . *Manfred Bissinger, Hans-Ulrich Jörges: ''Der unbequeme Präsident. Roman Herzog im Gespräch mit Manfred Bissinger und Hans-Ulrich Jörges''. Hoffman und Campe, Hamburg 1995, . *Stefan Reker: ''Roman Herzog''. Edition q, Berlin 1995, . *Werner Filmer, Heribert Schwan: ''Roman Herzog – Die Biographie''. Goldmann, Munich 1996, .External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Herzog, Roman 1934 births 2017 deaths 20th-century presidents of Germany People from Landshut German Lutherans Christian Democratic Union of Germany politicians Presidents of Germany Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni Free University of Berlin faculty Justices of the Federal Constitutional Court Honorary members of the Romanian Academy Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences German scholars of constitutional law Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana, 1st Class Recipients of the Grand Star of the Decoration for Services to the Republic of Austria Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Recipients of the Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg