Roman funerary art changed throughout the course of the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and the

Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

and comprised many different forms. There were two main burial practices used by the Romans throughout history, one being cremation, another inhumation. The vessels used for these practices include

sarcophagi

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek ...

,

ash chests, urns, and altars. In addition to these,

mausoleums,

stele, and other monuments were also used to commemorate the dead. The method by which Romans were memorialized was determined by social class, religion, and other factors. While monuments to the dead were constructed within Roman cities, the remains themselves were interred outside the cities.

After the end of

Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

** Etrusca ...

rule, Roman lawmakers became very strict regarding laying the dead to rest. A prime issue was the legality and morality of interring the dead within the city limits. It was nearly unanimous at first to move the dead outside of the ''

pomerium

The ''pomerium'' or ''pomoerium'' was a religious boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its ''pomerium''; everything beyond it was simply territory ('' ager'') belonging to Rome. ...

'' to ensure the separation of their souls from the living, and many politicians remained assertive in enforcing the idea well into the Empire.

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

reminds his readers of the

Laws of the Twelve Tables: "A dead man shall not be buried or burned inside the city" (''

De Legibus

The ''De Legibus'' (''On the Laws'') is a dialogue written by Marcus Tullius Cicero during the last years of the Roman Republic. It bears the same name as Plato's famous dialogue, '' The Laws''. Unlike his previous work ''De re publica,'' in wh ...

'', 2, 23:58). Three centuries later,

Paulus writes in his

Sententiae

''Sententiae'', the nominative plural of the Latin word ''sententia'', are brief moral sayings, such as proverbs, adages, aphorisms, maxims, or apophthegms taken from ancient or popular or other sources, often quoted without context. ''Sententia' ...

, "You are not allowed to bring a corpse into the city in case the sacred places in the city are polluted. Whoever acts against these restrictions is punished with unusual severity. You are not allowed to cremate a body within the walls of the city" (1, 21:2-3). Many Roman towns and

provinces

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

had similar rules, often in their charters, such as the ''

Lex Ursonensis''. Particularly at the very end of the Republic, exceptions to this principle became more frequent, albeit only for the most powerful leaders. The means used to commemorate the dead served to acknowledge the gods, but also served as means of social expression depicting Roman values and history.

Early Christians continued this custom until

Late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

, but liked to be buried close to the graves of

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

s.

Catacombs and

funerary halls, that later became great churches, grew up around the graves of famous martyrs outside the walls of Rome.

Mausolea

Etymology

The mausoleum is so named for

Mausolus

Mausolus ( grc, Μαύσωλος or , xcr, ���𐊠���𐊸𐊫𐊦 ''Mauśoλ'') was a ruler of Caria (377–353 BCE) and a satrap of the Achaemenid Empire. He enjoyed the status of king or dynast by virtue of the powerful position created by ...

of

Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined ...

(377–353/2 BC), a ruler in what is now

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

. He was a profound patron of

Hellenistic culture

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. After, or perhaps before his death, his wife and sister

Artemisia

Artemisia may refer to:

People

* Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC), queen of Halicarnassus under the First Persian Empire, naval commander during the second Persian invasion of Greece

* Artemisia II of Caria (died 350 BC), queen of Caria under th ...

commissioned the

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus ( grc, Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ; tr, Halikarnas Mozolesi) was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC in Halicarnassus (present Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, an ...

as an enormous tomb for him above ground; it was one of the

Seven Wonders of the ancient world

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

, and much of the sculpture is now in Berlin. Such had been a trend in

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

during the centuries before Mausolus, as it was a means of further solidifying the memory of the prominent deceased. At the time, the ancient Mediterranean world was in the midst of a

revival of Greek ideologies, present in politics, religion, the arts, and social life. The

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

were no exception to this trend.

Occupants

Mausolea generally had multiple occupants because their space was so vast, although this notion took time to become commonplace in the Early Republic, as did the idea of "

burying" the dead above ground.

Mass burials were common, but only for the common folk. Royalty, politicians,

generals

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

, and the richest citizens originally shared a tomb with no more than their immediate family. Changes were gradual largely because

funerary practices tended to follow strict traditions, especially in the ancient world.

It took centuries to conceive the "Roman" concept of the mausoleum. Meanwhile, the idea of lavish decoration of burial sites remained present throughout the Republic and the Empire. In context, above ground structures of the Empire and Late Republic contained art suitable to the lives of the occupants the same way their underground alternatives did.

Locations

Few mausolea inside the ''pomerium'' predated the Empire. Most mausolea existed on designated burial grounds in the country, though city exemptions to the prohibition of mortuary buildings only increased during the Empire. It was also popular to build them along main roads so that they would be consistently visible to the public. A trend of the

Middle and Late Empire was to build mausolea on family property, even if it was within the city limits.

History

Pre-Republic

The Romans absorbed a great deal of

Etruscan funerary art practices. Above ground mausolea were still rare; underground tombs and

tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built ...

were far more common methods of burial. The

early Romans buried those who could not afford such accommodations in

mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of execution, although an exact ...

s or

cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

them.

Of the few mausolea that they did build during Rome's infancy, many fell to

ruins

Ruins () are the remains of a civilization's architecture. The term refers to formerly intact structures that have fallen into a state of partial or total disrepair over time due to a variety of factors, such as lack of maintenance, deliberate ...

under unknown circumstances. Their absence thus renders little indication of the Romans' mausoleum practices during these years. A notable exception is in Praeneste, or present day

Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

, where approximately forty early mausolea remain.

Early Republic

Etruscan influence remained, and there became more consistency in the styles of mausolea as Roman influence increased throughout the

Latin League

The Latin League (c. 7th century BC – 338 BC)Stearns, Peter N. (2001) ''The Encyclopedia of World History'', Houghton Mifflin. pp. 76–78. . was an ancient confederation of about 30 villages and tribes in the region of Latium near the ancient ...

. Structures from this era are rare, but as with the preceding centuries, most of those that the Romans built at this time no longer exist.

Mid Republic

Rome, along with the rest of the Mediterranean world, experienced a resurgence of

Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cul ...

, known as the

Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

.

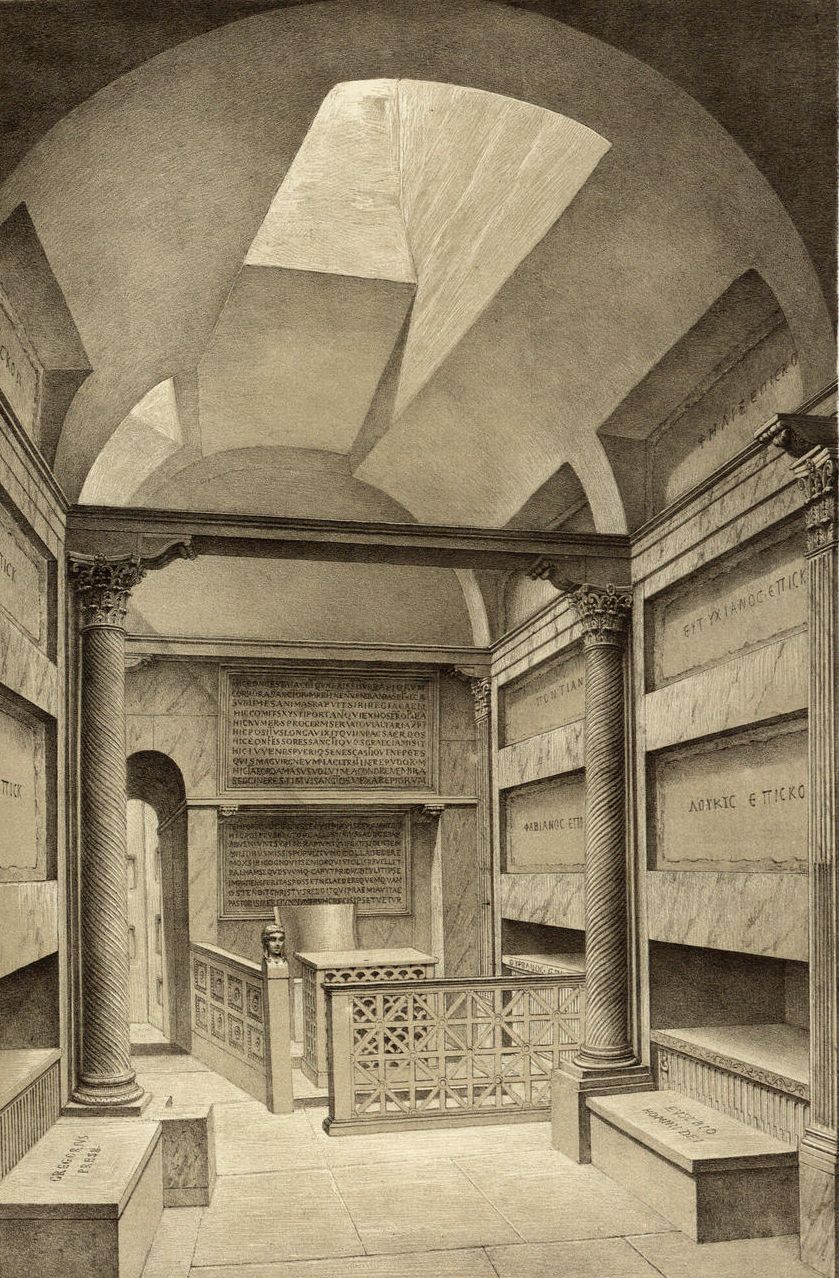

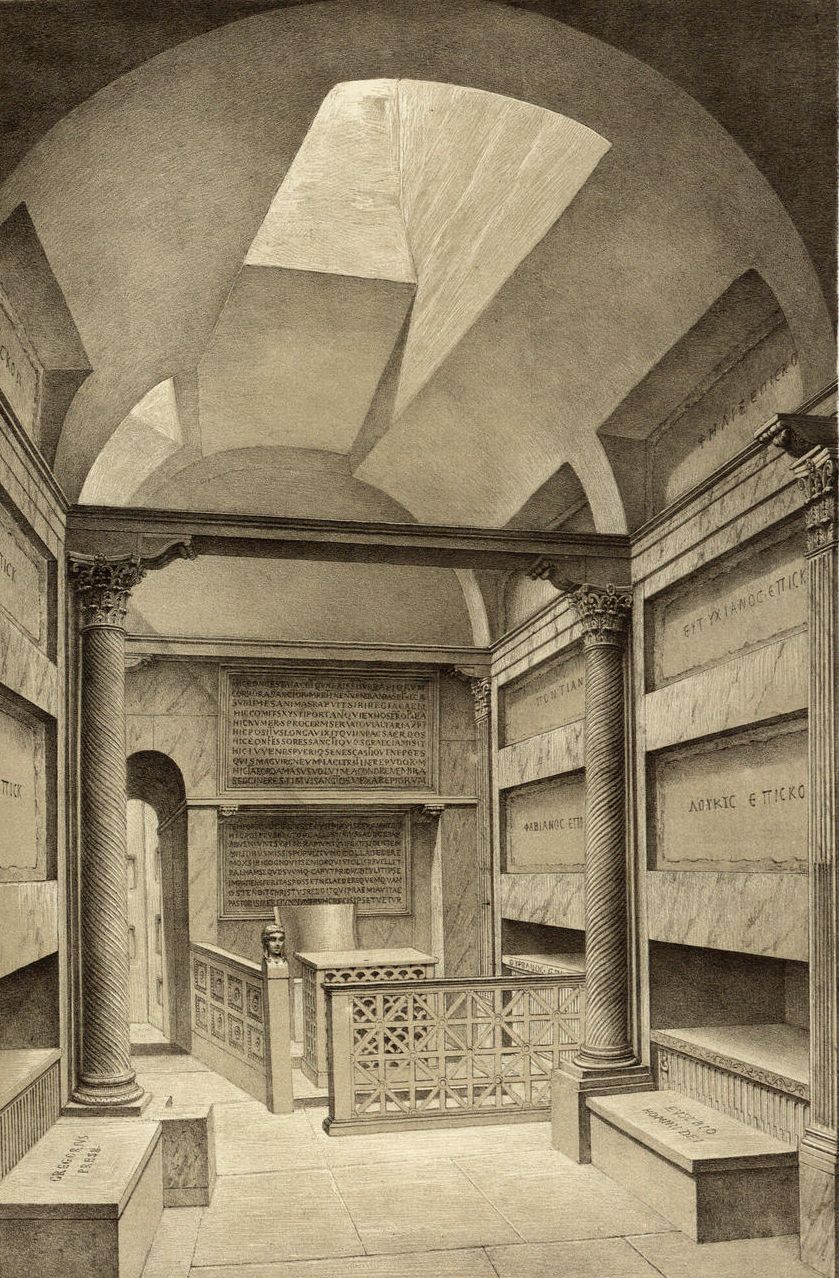

Both the interiors and exteriors of mausolea adopted staples of

Classical architecture

Classical architecture usually denotes architecture which is more or less consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or sometimes even more specifically, from the works of the Roman architect ...

such as

barrel vaulted roofs;

klinai, which were full body benches upon which the dead lay; painted

facades; ornate

columns

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression membe ...

; and

frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

s along the roofs. During this era, most Romans acknowledged the idea that above ground burial allows the public to better remember the deceased.

Clearly in accordance with their embraces of tradition and

virtues

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

of the

mos maiorum, Romans began to set aside money to build vast new mausolea for the preservation of their legacies. Of course, this trend was gradual, but had gained ground by the

end of the Republic.

The

Tomb of the Scipios

The Tomb of the Scipios ( la, sepulcrum Scipionum), also called the , was the common tomb of the patrician Scipio family during the Roman Republic for interments between the early 3rd century BC and the early 1st century AD. Then it was abandoned ...

is an example of a large underground rock-cut set of chambers used by the Scipio family from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC. It was grand, but relatively inconspicuous above ground.

Also present was an influence from the

lands east of Greece. Although the architectural contributions of

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

were very different from those of the Greeks, Asia Minor had previously opened itself to Hellenic styles earlier in the fourth century BC. The Romans borrowed most of their architecture during these years from the Greeks, so most of the Roman styles similar to those of Asia Minor actually came to Rome via Greece. Of course, the Romans borrowed directly from the Greek style as well. Anatolian mausolea are distinct via their tower designs, a notable example being the

Harpy Tomb

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approxi ...

, built circa 480–470 BC.

Nearing the Late Republic, the new diversity in design allowed those who could afford it to build larger and more lavish mausolea. Although politicians, particularly

senators, had always used their monuments to proclaim their status, they increasingly saw the grandeur of their mausolea as an additional outlet of expressing political dominance.

Around this time, most Romans had accepted the similarities of mausolea and

temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

, although their ancestors had been conscious of this apparent analogue for centuries.

Late Republic

Within the final two centuries of the Republic, Roman mausolea acquired inspiration from another geographical region:

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. North African architecture itself had succumbed to Greek practices since Greco-

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n

trade settlements since the eighth century BC. Again, the Romans embraced the style as they solidified their conquest of North Africa in the second and first centuries BC. By the time of

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, the influences of Greece, Asia Minor, and Africa combined to make a unique

"Roman" style.

As the Republic ended, more people continued to forgo the rules against city burials.

One of the last Republican leaders to do so was

Sulla, who opted to build a mausoleum on the

Campus Martius

The Campus Martius (Latin for the "Field of Mars", Italian ''Campo Marzio'') was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome about in extent. In the Middle Ages, it was the most populous area of Rome. The IV rione of Rome, Campo Marzio, which cove ...

. Many burial grounds outside of the city became crowded because mausolea had not but increased in size, ornateness, and quantity since the Hellenistic Era. In the first century BC, some Romans settled for smaller and simpler mausolea in order to just reserve space on a prominent burial ground, such as the

Isola Sacra Necropolis

{{Infobox ancient site

, name = Isola Sacra

, native_name =

, alternate_name = Necropoli di Porto

, image = Necropoli di Porto 03.JPG

, alt =

, caption = Necropolis of Portus

, map_type = Italy Lazio

, map_alt =

, coordinates = ...

outside of

Portus, where visitors can notice the smaller mausolea desperately filling random space around the more properly distanced larger ones.

Howard Colvin

Sir Howard Montagu Colvin (15 October 1919 – 27 December 2007) was a British architectural historian who produced two of the most outstanding works of scholarship in his field: ''A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840' ...

cites the mausolea of the

consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

Minicius Fundanus on

Monte Mario

Monte Mario (English: Mount Mario or Mount Marius) is the hill that rises in the north-west area of Rome (Italy), on the right bank of the Tiber, crossed by the Via Trionfale. It occupies part of Balduina, of the territory of Municipio Roma I ...

and the

Licinii

The gens Licinia was a celebrated plebeian family at ancient Rome, which appears from the earliest days of the Republic until imperial times, and which eventually obtained the imperial dignity. The first of the gens to obtain the consulship was ...

-

Calpurnii on

Via Salaria

The Via Salaria was an ancient Roman road in Italy.

It eventually ran from Rome (from Porta Salaria of the Aurelian Walls) to ''Castrum Truentinum'' ( Porto d'Ascoli) on the Adriatic coast, a distance of 242 km. The road also passed throug ...

as examples of more compact structures that came to scatter burial sites.

The

Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker

The tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the baker is one of the largest and best-preserved freedman funerary monuments in Rome. Its sculpted frieze is a classic example of the "plebeian style" in Roman sculpture. Eurysaces built the tomb for hims ...

(50–20 BC) is a flamboyant example of a rich

freedman's tomb, with reliefs exemplifying an Italic style less influenced by Hellenistic art than official or patrician monuments.

Early Empire

The

new government of Rome brought a new approach to mausolea politically and socially. The non-elite became ever present in the Senate, putting a damper on many of the longtime rivalries of the

aristocracy. Because they many of these men were ''

homines novi'', or new men, they had other incentives to assert dominance; Patterson observes that their mausolea focused more upon giving prestige to their own name rather than toppling that of someone else. Such an agenda is discernible through the increased interest of building mausolea on family property.

Many wealthy families owned magnificent estates in the country, where they were free from the burial laws of the city. While the art and design of the structures themselves remained grandiose, builders shifted interest to decorating the land around the mausoleum. Statues,

podia,

steles, and horti (gardens), gained popularity amongst those who had the space and money to erect mausolea on their own property. The

Pyramid of Cestius

The pyramid of Cestius (in Italian, ''Piramide di Caio Cestio'' or ''Piramide Cestia'') is a Roman Era pyramid in Rome, Italy, near the Porta San Paolo and the Protestant Cemetery. It was built as a tomb for Gaius Cestius, a member of the Epu ...

of about 12 BC remains a rather eccentric Roman landmark; he had perhaps served in

Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

n campaigns.

With the advent of the Empire came an extreme augmentation in the inclusivity of mausolea on two ways. First, the occupation of many new mausolea was greater than that of their Republican predecessors, which generally reserved space for nobody other than their immediate family. Many in the Empire who commissioned mausolea in their name also requested room for extended family,

slaves,

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

,

concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

s,

clients, animals, and other intimate acquaintances.

Second, more people who could normally not afford a mausoleum were able to acquire one. Aside from those a master invited to his mausoleum, certain freedmen received their own mausoleum with financial assistance from their former masters. Some of the freedmen's mausolea are equally as impressive as those of wealthy citizens.

Late Empire

No later than the end of the second century AD did Rome reach its territorial apex as an empire. The initially slow, but quickly hastening

decline of the Empire allowed the mausoleum to fall into the hands of Roman constituents and

enemies

Enemies or foes are a group that is seen as forcefully adverse or threatening.

Enemies may also refer to:

Literature

* ''Enemies'' (play), a 1906 play by Maxim Gorky

* '' Enemies, A Love Story'', a 1966 novel by Isaac Bashevis Singer

* '' Enem ...

. Notably, after the

Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensio ...

, the revival of the mausoleum during the

Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

and beyond spawned interest amongst the

Christian population. They began to build mausolea in the same edificial style as the Romans had for the duration of the Empire, and decorated them with

Christian art

Christian art is sacred art which uses subjects, themes, and imagery from Christianity. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, including early Christian art and architecture and Christian media.

Images of Jesus and narrati ...

work. Mausolea continued to be a prime means of interring multiple individuals in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

The

Mausoleum of Helena

The Mausoleum of Helena is an ancient building in Rome, Italy, located on the Via Casilina, corresponding to the 3rd mile of the ancient Via Labicana. It was built by the Roman emperor Constantine I between 326 and 330, originally as a tomb for ...

in Rome, built by

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

for himself, but later used for his mother, remains a traditional form, but the church of

Santa Costanza

Santa Costanza is a 4th-century church in Rome, Italy, on the Via Nomentana, which runs north-east out of the city. It is a round building with well preserved original layout and mosaics. It has been built adjacent to a horseshoe-shaped church, n ...

there, built as a mausoleum for Constantine's daughter, was built over an important catacomb where

Saint Agnes

Agnes of Rome () is a virgin martyr, venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, Oriental Orthodox Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, as well as the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Churches. St. Agnes is one of several virgin martyrs co ...

was buried, and either was always intended, or soon developed as, a

funerary hall where burial spots could be bought by Christians. Most of the great Christian

basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's Forum (Roman), forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building ...

s in Rome passed through a stage as funerary halls, full of sarcophagi and slab memorials, before being turned into more conventional churches in the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

.

Notable Mausolea of Emperors

Augustus

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

did the unspeakable in 28 BC and erected a mausoleum on the

Campus Martius

The Campus Martius (Latin for the "Field of Mars", Italian ''Campo Marzio'') was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome about in extent. In the Middle Ages, it was the most populous area of Rome. The IV rione of Rome, Campo Marzio, which cove ...

, a previously public land upon which infrastructure was normally illegal. This challenged his claim to be ''

princeps

''Princeps'' (plural: ''principes'') is a Latin word meaning "first in time or order; the first, foremost, chief, the most eminent, distinguished, or noble; the first man, first person". As a title, ''princeps'' originated in the Roman Republic w ...

'', as his enemies found such an action to be too ambitious for a regular

citizen and thus above the law. Notable features of the mausoleum included a bronze statue of Augustus,

pyre

A pyre ( grc, πυρά; ''pyrá'', from , ''pyr'', "fire"), also known as a funeral pyre, is a structure, usually made of wood, for burning a body as part of a funeral rite or execution. As a form of cremation, a body is placed upon or under the ...

s, and

Egyptian obelisks among the various usual mortuary ornaments. The mausoleum suffered severe destruction in 410 AD during the

Gothic invasion of Rome in 410 AD.

Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian had a grand mausoleum, now better known as the

Castel Sant'Angelo, for himself and his family in the

Pons Aelius

Pons Aelius (Latin for "Aelian Bridge"), or Newcastle Roman Fort, was an auxiliary castra and small Roman settlement on Hadrian's Wall in the Roman province of Britannia Inferior (northern England), situated on the north bank of the River Ty ...

in 120 AD. In addition to its fame as the resting spot of the emperor, the construction of the mausoleum is famous in its own right, as it has a particularly complex vertical design. A rectangular base supports the usual cylindrical frame. Atop the frame is a garden roof with a

baroque monument bearing the statue of an angel. The original statue, that of a golden

quadriga

A () is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in Classical Antiquity and the Roman Empire until the Late Middle Ages. The word derives from the Latin contraction of , from ': four, and ': yoke.

The four- ...

, among other treasures fell victim to various attacks when the mausoleum served as a castle and a papal fortress during the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. Over a century would pass before a new mausoleum would house the remains of an emperor. The corruption of the

Severans and the

Third Century Crisis

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensi ...

did not permit very much opportunity for such a glorious memorialization.

The Tetrarchy

Diocletian,

Maxentius,

Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, and

Constantius I

Flavius Valerius Constantius "Chlorus" ( – 25 July 306), also called Constantius I, was Roman emperor from 305 to 306. He was one of the four original members of the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian, first serving as caesar from 293 t ...

all had their own mausolea.

Diocletian and Galerius, who ruled the

Eastern Empire, have particularly visible eastern influences in their mausolea, now both churches.

Viewers can observe the tower in the former's building, built on

Diocletian's Palace

Diocletian's Palace ( hr, Dioklecijanova palača, ) is an ancient palace built for the Roman emperor Diocletian at the turn of the fourth century AD, which today forms about half the old town of Split, Croatia. While it is referred to as a "pala ...

in

Split, Croatia

)''

, settlement_type = City

, anthem = ''Marjane, Marjane''

, image_skyline =

, imagesize = 267px

, image_caption = Top: Nighttime view of Split from Mosor; 2nd row: Cathedra ...

and the dark oil murals on the interior of the latter's, in

Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. Diocletian's mausoleum is now the main part of

Split Cathedral. The

Mausoleum of Maxentius outside Rome is the only one of the four in Italy. It lies on the

Via Appia

The Appian Way (Latin and Italian: ''Via Appia'') is one of the earliest and strategically most important Roman roads of the ancient republic. It connected Rome to Brindisi, in southeast Italy. Its importance is indicated by its common name, ...

, where his

villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

and

circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclis ...

lie in ruins. Colvin asserts that the army likely buried Constantius in

Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

, but there is no material evidence.

Funerary altars

In ancient Rome, Roman citizens would memorialize their dead by creating ''

cippi

A (plural: ''cippi''; "pointed pole") is a low, round or rectangular pedestal set up by the Ancient Romans for purposes such as a milestone or a boundary post. They were also used for somewhat differing purposes by the Etruscans and Carthaginians ...

'' or grave altars. These altars became, not just commissioned by the rich, but also commonly erected by freedmen and slaves. The function of these altars was either to house the ashes of the dead or just to symbolically commemorate the memory of the deceased.

Often, practical funerary altars were constructed to display vessels that contained the ashes and burnt bones of the deceased. These ash urns were placed in deep cavities of the altars that were then covered with a lid.

Other times, there was a depression in the altar in which libations could be poured. Some Roman funerary altars were provided with pipes so that these libations could "nourish" the remains.

Less commonly, the body of the deceased was placed in the altar.

While some altars contained remnants of the deceased, most Roman funerary altars had no practical function and only were erected to memorialize the dead.

Funerary altars versus votive altars

The practice of erecting Roman funerary altars is linked to the tradition of constructing votive altars to honor the gods. Due to the acceptance that altars act as a symbol of reverence, it is believed that funerary altars were used to heroicize the deceased. Funerary altars differed from votive altars that honored the gods, because they were not recipients of blood

sacrifices. Grave altars of heroes were connected with ritual sacrifices, but altars of regular Roman citizens were not. This practical difference is determined because Roman funerary altars do not have sacrificial pans or braziers. By having a similar appearance to votive altars, the symbolism of the reverence of a sacrifice was implied, therefore conveying proper respect to the dead.

While having different meanings, the two types of altars were similarly constructed, both aboveground and round or rectangular in shape.

Locations

Funerary altars of more wealthy Roman citizens were often found on the interior of more elaborate tombs.

Altars erected by the middle class were also set up in or outside of monumental tombs, but also in funerary precincts that lined the roads leading out of the city of Rome.

The altars that were part of tomb complexes were set up on family plots or on building plots bought by speculators, who then sold them to individual owners. Tombs and altars had a close connection in the mind of a Roman, evidenced by the Latin inscriptions where tombs are described as if they were altars.

Importance of epitaph

Epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

s on funerary altars provide much information about the deceased, most often including their name and their filiation or tribe.

Less often, the age and profession of the deceased was included in the epitaph.

A typical epitaph on a Roman funerary altar opens with a dedication to the

manes

In ancient Roman religion, the ''Manes'' (, , ) or ''Di Manes'' are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the ''Lares'', '' Lemures,'' '' Genii'', and ''Di Penates'' as deities ( ...

, or the spirit of the dead, and closes with a word of praise for the honoree.

These epitaphs, along with the pictorial attributes of the altars, allow historians to discern a lot of important information about ancient

Roman funerary practices

Roman funerary practices include the Ancient Romans' religious rituals concerning funerals, cremations, and burials. They were part of time-hallowed tradition ( la, mos maiorum), the unwritten code from which Romans derived their social norm ...

and monuments. Gathered from the funerary altars, it can be established that the majority of the altars were erected by a homogeneous group of middle-class citizens.

Dedicants and honorees

Epitaphs often emphasize the relationship between the deceased and dedicant, with most relationships being familial (husbands and wives, parents and children, etc.). Many altars also feature portraits of the deceased.

Extrapolated from the evidence of epitaphs and portraits on the altars, it can be concluded that

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

and their descendants most frequently commissioned funerary altars in Rome—people who were teachers, architects, magistrates, writers, musicians and so on.

The most common type of altar dedication is from parents to their deceased child. The epitaph often features the age of the child to further express grief at the death at such a young age. On the other hand, the age of a deceased person at an older age is rarely put on the epitaph.

Some other, less common, dedications are to parents from children, with the child most likely being a boy. The second most common relationship of honorees is husband to wife or wife to husband.

Outside of familial relationships, patrons sometimes dedicated altars to a slave or freedman and vice versa. The relationship between dedicant and honoree of some altars that support this conclusion were actually husband and wife, because patrons sometimes married their freed slaves.

However, the relationship between patron and slave or freedman was not exclusionary to marriage, because sometimes these citizens had a personal relationship with a non-blood related person that they felt needed to be commemorated.

It is important to note the prominence of women surrounding the discussion of Roman funerary altars, because it is rare for ancient Roman women to be so involved in any kind of monument of this time. Contrasting to most of the monuments that are surviving from Rome, women played a major part in funerary altars because many altars were erected in honor of or commissioned by a woman.

These women were honored as wives, mothers, and daughters, as well remembered for their professions. For example, these professional women were honored as

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

esses, musicians, and poets. Sometimes the epitaph does not altar information about the profession of the honored woman, but details of the portrait (for example, the dress of the portrait) give clues to her vocation. Many surviving altars honor women because, in ancient Rome, women tended to die young, due to childbirth and general hardships from marriage and overwork. Roman women were honored often honored by their husbands, with some altars dedicated to the pair and with some just honoring the wife. Furthermore, some female children were honored in altars, commissioned by their grief-stricken parents.

Designs

Roman funerary altars had varied structures, with most reflecting the erection design of votive altars, which have flat tops. For others, which most likely were designed to receive offerings, the tops of the altars were dished.

Deeper cavities were created for ash urns to be placed inside.

Sizes of the altars could range from miniature examples to 2 meters tall.

Some carried busts or statues or portraits of the deceased.

The simplest and most common form of a funerary altar was a base with a

pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

, often featuring a portrait or epitaph, on top of the base. They are almost all rectangular in shape and taller than they are wide. Plain or spiral columns usually frame the portrait or scene featured on the altar.

Along with the typical portrait and epitaph, other motifs were inscribed in the altars. These motifs often had otherworldly or funerary meanings, which include

laurel wreath

A laurel wreath is a round wreath made of connected branches and leaves of the bay laurel (), an aromatic broadleaf evergreen, or later from spineless butcher's broom (''Ruscus hypoglossum'') or cherry laurel (''Prunus laurocerasus''). It is a s ...

s or fruit –swags. Mythological allusions in the design of the altar often aimed to liken the deceased to a divine being. Examples of these allusions include a young girl who is represented in the guise of

Daphne

Daphne (; ; el, Δάφνη, , ), a minor figure in Greek mythology, is a naiad, a variety of female nymph associated with fountains, wells, springs, streams, brooks and other bodies of freshwater.

There are several versions of the myth in whi ...

transformed into a laurel tree or another girl who is portrayed as the goddess

Diana. Sometimes, tools that were characteristic of the deceased's profession were featured on the altar. The design of the Roman funerary altars differs between each individual altar, but there are many overarching themes.

Sarcophagi

''"...a stone monument is an expression of permanence. It is no surprise, therefore, that the Roman obsession with personal immortality acquired its physical form in stone."''

Sarcophagi were used in Roman funerary art beginning in the second century AD, and continuing until the fourth century. A sarcophagus, which means "flesh-eater" in Greek, is a stone coffin used for inhumation burials.

Sarcophagi were commissioned not only for the elite of Roman society (mature male citizens),

but also for children, entire families, and beloved wives and mothers. The most expensive sarcophagi were made from marble, but other stones, lead, and wood were used as well.

Along with the range in production material, there existed a variety of styles and shapes, depending on where the sarcophagus was produced and whom it was produced for.

Before sarcophagi

Inhumation burial practices and the use of sarcophagi were not always the favored Roman funerary custom. The

Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

** Etrusca ...

s and Greeks used sarcophagi for centuries before the Romans finally adopted the practice in the second century.

Prior to that period, the dead were usually cremated and placed in marble ash chests or ash altars, or were simply commemorated with a grave altar that was not designed to hold cremated remains. Despite being the main funerary custom during the Roman Republic, ash chests and grave altars virtually disappeared from the market only a century after the advent of the sarcophagus.

It is often assumed that the popularity for sarcophagi began with the Roman aristocracy and gradually became more accepted by the lower classes.

However, in the past, the most expensive and ostentatious grave altars and ash chests were commissioned more frequently by wealthy freedmen and other members of the emerging middle class than by the Roman elite. Due to this fact and the lack of inscriptions on early sarcophagi, there is not enough evidence to make a judgment on whether or not the fashion for sarcophagi began with a specific social class. Surviving evidence does indicate that a great majority of early sarcophagi were used for children. This suggests that the change in burial practice may not have simply stemmed from a change in fashion, but perhaps from altered burial attitudes. It is possible that the decision to begin inhuming bodies occurred because families believed that inhumation was a kinder, and less disturbing burial rite than cremation, thus necessitating a shift in burial monument.

Stylistic transition from altars and ash chests to sarcophagi

Although grave altars and ash chests virtually disappeared from the market in the second century, aspects of their decoration endured in some stylistic elements of sarcophagi. The largest stylistic group of early sarcophagi in the second century is garland sarcophagi, a custom of decoration that was previously used on ash chests and grave altars. Though the premise of the decoration is the same, there are some differences. The garland supports are often human figures instead of the animal heads used previously. In addition, specific mythological scenes fill the field, rather than small birds or other minor scenes. The inscription panel on garland ash altars and chests is also missing on garland sarcophagi. When a sarcophagus did have an inscription, it seemed to be an extra addition and usually ran along the top edge of the chest or between the decorations. The fact that early garland sarcophagi continued the tradition of grave altars with decorated garlands suggests that the customers and sculptors of sarcophagi had similar approaches to those who purchased and produced grave altars. Both monuments employed a similar collection of stylistic motifs with only subtle shifts in iconography.

Metropolitan Roman, Attic, and Asiatic sarcophagus production centers

Sarcophagi production of the Ancient Roman Empire involved three main parties: the customer, the sculpting workshop that carved the monument, and the quarry-based workshop that supplied the materials. The distance between these parties was highly variable due to the extensive size of the Empire. Metropolitan Roman, Attic, and Asiatic were the three major regional types of sarcophagi that dominated trade throughout the Roman Empire.

Although they were divided into regions, the production of sarcophagi was not as simple as it might appear. For example, Attic workshops were close to

Mount Pentelikon, the source of their materials, but were usually very far from their client. The opposite was true for the workshops of Metropolitan Rome, who tended to import large, roughed out sarcophagi from distant quarries in order to complete their commissions. Depending on distance and customer request (some customers might choose to have elements of their sarcophagi left unfinished until a future date, introducing the possibility of further work after the main commission), sarcophagi were in many different stages of production during transport. As a result, it is difficult to develop a standardized model of production.

Metropolitan Rome

Rome was the primary production center in the western part of the empire. A Metropolitan Roman sarcophagus often took the shape of a low rectangular box with a flat lid. As the sarcophagus was usually placed in a niche or against a wall in a mausoleum, they were usually only decorated on the front and two shorter sides. Many were decorated with carvings of garlands and fruits and leaves, as well as narrative scenes from Greek mythology. Battle and hunting scenes, biographical events from the life of the deceased, portrait busts, the profession of the deceased and abstract designs were also popular.

Attic

Athens was the main production center for Attic style sarcophagi. These workshops mainly produced sarcophagi for export. They were rectangular in shape and were often decorated on all four sides, unlike the Metropolitan Roman style, with ornamental carvings along the bottom and upper edge of the monument. The lids were also different from the flat metropolitan Roman style and featured a pitched gable roof,

or a kline lid, which is carved in the style of couch cushions on which the form of the deceased reclines. The great majority of these sarcophagi also featured mythological subjects, especially the

Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ...

, Achilles, and battles with the

Amazons.

Asia Minor (Asiatic)

The

Dokimeion workshops in

Phrygia specialized in architecturally formed large-scale Asiatic sarcophagi. Many featured a series of columns joined together by an entablature on all four sides with human figures in the area between the columns. The lids were often made in the gabled-roof design in order to complete the architectural-style sarcophagi so the coffin formed a sort of house or temple for the deceased. Other cities in Asia Minor produced sarcophagi of the garland tradition as well. In general, the sarcophagi were decorated on either three or four sides, depending on whether they were to be displayed on a pedestal in an open-air setting or against the walls inside tombs.

Myth and meaning on Ancient Roman sarcophagi

A transition from the classical garland and seasonal reliefs with smaller mythological figures to a greater focus on full mythological scenes began with the break up of the classical style in the late second century towards the end of

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

' reign. This shift led to the development of popular themes and meanings portrayed through mythological scenes and allegories. The most popular mythological scenes on Roman sarcophagi functioned as aids to mourning, visions of life and happiness, and opportunities for self-portrayal for Roman citizens. Images of

Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, grc-gre, Μελέαγρος, Meléagros) was a hero venerated in his ''temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Ho ...

, the host of the

Calydonian Boar

The Calydonian boar hunt is one of the great heroic adventures in Greek legend. It occurred in the generation prior to that of the Trojan War, and stands alongside the other great heroic adventure of that generation, the voyage of the Argonauts, ...

hunt, being mourned by Atalanta, as well as images of

Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's '' Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Pele ...

mourning

Patroclus were very common on sarcophagi that acted as grieving aids. In both cases, the mythological scenes were akin to mourning practices of ordinary Roman citizens in an effort to reflect their grief and comfort them when they visited the tomb. Playful images depicting

Nereid

In Greek mythology, the Nereids or Nereides ( ; grc, Νηρηΐδες, Nērēḯdes; , also Νημερτές) are sea nymphs (female spirits of sea waters), the 50 daughters of the ' Old Man of the Sea' Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters ...

s, Dionysiac triumphs, and love scenes of

Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Roma ...

and

Ariadne

Ariadne (; grc-gre, Ἀριάδνη; la, Ariadne) was a Cretan princess in Greek mythology. She was mostly associated with mazes and labyrinths because of her involvement in the myths of the Minotaur and Theseus. She is best known for havi ...

were also commonly represented on sarcophagi. It is possible that these scenes of happiness and love in the face of death and mourning encouraged the living to enjoy life while they could, and reflected the celebration and meals that the mourners would later enjoy in the tomb when they returned to visit the deceased. The third century involved the return in popularity of self-representation on Roman sarcophagi. There were several different ways Roman citizens approached self-representation on sarcophagi. Some sarcophagi had actual representations of the face or full figure of the deceased. In other cases, mythological portraits were used to connect characteristics of the deceased with traits of the hero or heroine portrayed. For example, common mythological portraits of deceased women identified them with women of lauded traits in myth, such as the devoted

Selene

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Selene (; grc-gre, Σελήνη , meaning "Moon"''A Greek–English Lexicon's.v. σελήνη) is the goddess and the personification of the Moon. Also known as Mene, she is traditionally the daughter of ...

or loyal

Alcestis

Alcestis (; Ancient Greek: Ἄλκηστις, ') or Alceste, was a princess in Greek mythology, known for her love of her husband. Her life story was told by pseudo-Apollodorus in his '' Bibliotheca'', and a version of her death and return from t ...

. Scenes featuring the figures of Meleager and Achilles expressed bravery and were often produced on sarcophagi holding deceased men.

Biographical scenes that emphasize the true virtues of Roman citizens were also used to commemorate the deceased. Scholars argue that these biographical scenes as well as the comparisons to mythological characters suggest that self-portrayal on Roman sarcophagi did not exist to celebrate the traits of the deceased, but rather to emphasize favored Roman cultural values and demonstrate that the family of the deceased were educated members of the elite that could understand difficult mythological allegories.

Third- and fourth-century sarcophagi

The breakup of the classical style led to a period in which full mythological reliefs with an increase in the number of figures and an elongation of forms became more popular, as discussed above. The proportion of figures on the reliefs also became increasingly unbalanced, with the main figures taking up the greatest area with smaller figures crowded in the small pockets of empty space. In the third century, another transition in theme and style of sarcophagi involved the return in popularity of representing mythological and non-mythological portraits of the deceased. Imagery of the four seasons also becomes popular during the third and fourth centuries. With the advent of Christianity in the third century, traditional motifs, like the seasons, remained, and images representing a belief in the afterlife appeared. The change in style brought by Christianity is perhaps most significant, as it signals a change in emphasis on images of retrospection, and introduced images of an afterlife.

Catacombs

The Roman catacombs are a series of underground cemeteries that were built in several major cities of the Roman Empire, beginning in the first and second centuries BC. The tradition was later copied in several other cities around the world, though underground burial had been already common in many cultures before Christianity. The word "Catacomb" means a large, underground, Christian cemetery. Because of laws prohibiting burial within the city, the catacombs were constructed around the city along existing roads such as the

Via Appia

The Appian Way (Latin and Italian: ''Via Appia'') is one of the earliest and strategically most important Roman roads of the ancient republic. It connected Rome to Brindisi, in southeast Italy. Its importance is indicated by its common name, ...

, where San Callixtus and San Sebastiano can be found, two of the most significant catacombs.

The catacombs were often named for saints who were buried in them, according to tradition, though at the time of their burial, martyr cults had not yet achieved the popularity to grant them lavish tombs.

After 750 BC, most of the remains of these martyrs were moved to the churches in the city above.

This was mainly undertaken by

Pope Paul I, who decided to move the relics because of the neglected state of the catacombs. The construction of catacombs started late in the first century and during this time they were used only for burial purposes and for funerary rites. The process of underground burial was abandoned, however, in the fifth century. A few catacombs remained open to be used as sites of pilgrimage because of their abundance of relics.

Before Christians began to use catacombs for burial, they buried their dead in pagan burial areas. As a result of their community's economic and organizational growth, Christians were able to begin these exclusively Christian cemeteries. Members of the community created a "communal fund" which ensured that all members would be buried. Christians also insisted on inhumation and the catacombs allowed them to practice this in an organized and practical manner.

Types of tombs

The layout and architecture was designed to make very efficient use of the space and consisted of several levels with skylights that were positioned both to maximize lighting and to highlight certain elements of the decor. There are several types of tomb in the catacombs, the simplest and most common of which is the ''

loculus Loculus may refer to:

*Loculus (satchel)

*Loculus (architecture), a burial niche

*An alternative name for a locule, or compartment in an organism.

*Loculus of Archimedes or Ostomachion

''Ostomachion'', also known as ''loculus Archimedius'' ...

'' (pl. ''loculi''), a cavity in the wall closed off by marble or terra-cotta slabs. These are usually simple and organized very economically, arranged along the walls of the hallways in the catacombs. A ''mensa'' is a niche in the wall holding a sarcophagus while a ''cubiculus'' is more private, more monumental, and usually more decorated.

''Cubicula'' use architectural structures, such as columns, pilasters, and arches, along with bold geometric shapes. Their size and elaborate decor indicate wealthier occupants. With the issuance of the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, as Christians were less persecuted and gained more members of the upper class, the catacombs were greatly expanded and grew more monumental.

Types of decor

Material of tombs

Much of the material of the tombs was second-hand, some even still has pagan inscriptions on them from their previous use. Marble was used often, partially because it reflected light and was light in color. Clay bricks were the other common material that was used for structure and for decor.

Roman concrete

Roman concrete, also called , is a material that was used in construction in ancient Rome. Roman concrete was based on a hydraulic-setting cement. It is durable due to its incorporation of pozzolanic ash, which prevents cracks from spreading. ...

(volcanic rock, lime putty, and water – a combination which is incredibly resistant to wear) and a thin layer of stucco was spread over the walls of bare rock faces. This was not structural, only aesthetic, and was typically painted with frescoes.

Inscriptions

Tombs were usually marked with epitaphs, seals, Christian symbols, or prayers in the form of an inscription or painted in red lead, though often they were marked only with the name of the occupant.

Inscriptions in the Christian catacombs were usually in Latin or Greek, while in the Jewish catacombs they were written in either Greek or Hebrew. The majority of them are religiously neutral, while some are only graphic imitations of epitaphs (dashes and letters) that serve no meaning but to continue the funerary theme in an anonymous and efficient mass-production. Textual inscriptions also contained graphic elements and were matched in size and significance with decorative elements and elaborate punctuations marks. Some Christians were too poor to afford inscriptions, but could inscribe their tomb with a short and somewhat sloppy

graffito while the mortar was still drying; Eventually, a code of equality was established ensuring that the tombs of poorer Christians would still be decorated, however minimally. The quality of writing on pagan tombstones is noticeably superior to that on Christian tombstones. This was probably due to the fact that Christians had less means, less access to specialized workers, and perhaps care more about the content of their inscriptions than their aesthetic.

Objects

Objects were often set before, in, and in the mortar of tombs. These took the form of benches, stools, tables, and tableware and may have been used for rites such as the ''

refrigerium'' (the funerary meal) which involved real food and drink.

Tables most likely held offerings of food while vases or other glass or ceramic containers held offerings of wine. Objects such as the bases of

gold glass

Gold glass or gold sandwich glass is a luxury form of glass where a decorative design in gold leaf is fused between two layers of glass. First found in Hellenistic Greece, it is especially characteristic of the Roman glass of the Late Empire ...

beakers, shells, dolls, buttons, jewelry, bells, and coins were added to the mortar of the ''loculi'' or left on shelves near the tomb. Some of these objects may have been encased in the tomb with the body and removed later. Objects were much more common during and after the Constantinian period.

Frescoes

The objects surrounding the tomb were reflected in the frescoes of banquets. The tombs sometimes used mosaics, but frescoes were overwhelmingly more popular than mosaics. The walls were typically whitewashed and divided up into sections by red and green lines. This shows influence from Pompeian wall painting which tends toward extreme simplification of architectural imitation.

''"The Severan period sees the definition of the wall surface as a chromatic unity, no longer intended as a space open towards an illusionary depth, but rather as a solid and substantial surface to be articulated with panels."''

Symbolism

The organized and simple style of the frescoes manifests itself in two forms: an imitation of architecture, and clearly defined images. The images typically present one subject of religious importance and are combined together to tell a familiar (typically Christian) story. Floral motif and the Herculean labors (often used in pagan funerary monuments) along with other Hellenistic imagery are common and merge in their depictions of nature with Christian ideas of Eden. Similarly, seasons are a common theme and represent the journey through life from birth (spring) to death (winter), which goes with the occasional depictions of the Goddesses Ceres and Proserpina. There are many examples of pagan symbolism in the Christian catacombs, often used as parallels to Christian stories. The phoenix, a pagan symbol, is used to symbolize the Resurrection;

Hercules in the Garden of Hesperides symbolizes Adam, Eve, and the Serpent in the garden of Eden; the most famous symbol of the catacombs, the

Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd ( el, ποιμὴν ὁ καλός, ''poimḗn ho kalós'') is an image used in the pericope of , in which Jesus Christ is depicted as the Good Shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep. Similar imagery is used in Psalm 23 ...

is sometimes shown as Christ, but sometimes as the Greek figure Orpheus.

Most usage of pagan imagery is to emphasize paradisial aspects, though it may also indicate that either the patron or the artist was pagan. Other symbols include historical martyrs, funerary banquets, and symbols of the occupation of the deceased. The most popular symbols are of the Jonah cycle, the Baptism of Christ, and the Good Shepherd and the fisherman. The Good Shepherd was used as a wish for peaceful rest for the dead, but also acted as a guide to the dead who were represented by the sheep. Sometimes the Good Shepherd was depicted with the fisherman and the philosopher as the symbol of ultimate "peace on land and sea," though this is only briefly popular. These Old Testament scenes are also seen in Jewish catacombs.

Tombstones and funerary inscriptions

Culturally significant throughout the Empire, the erection and dedication of funerary tombstones was a common and accessible burial practice.

As in modern times, epitaphs were a means of publicly showcasing one's wealth, honor, and status in society.

In this way, tombstones not only served to commemorate the dead, but also to reflect the sophistication of the Roman world.

Both parties, therefore – the living and the dead – were venerated by and benefited from public burial. Though Roman tombstones varied in size, shape, and style, the epitaphs inscribed upon them were largely uniform.

Traditionally, these inscriptions included a prayer to the

Manes

In ancient Roman religion, the ''Manes'' (, , ) or ''Di Manes'' are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the ''Lares'', '' Lemures,'' '' Genii'', and ''Di Penates'' as deities ( ...

, the name and age of the deceased, and the name of the commemorator. Some funerary inscriptions, though rare, included the year, month, day, and even hour of death. The design and layout of the epitaph itself would have often been left to the discretion of a hired stonemason.

In some cases, the stonemason would have even chosen the inscription, choosing a common phrase to complement the biographical information provided by the family of the deceased. In death, one had the opportunity to idealize and romanticize their accomplishments; consequently, some funerary inscriptions can be misleading. Tombstones and epitaphs, therefore, should not be viewed as an accurate depiction of the Roman demographic.

Freedmen and their children

In the Roman world, infant mortality was common and widespread throughout the Empire. Consequently, parents often remained emotionally detached from young children, so as to prevent or lessen future grief. Nonetheless, tombstones and epitaphs dedicated to infants were common among freedmen.

Of the surviving collection of Roman tombstones, roughly 75 percent were made by and for freedmen and slaves. Regardless of class, tombstones functioned as a symbol of rank and were chiefly popular among those of servile origin. As public displays, tombstones were a means of attaining social recognition and asserting one's rise from slavery. Moreover, tombstones promoted the liberties of

freeborn

"Freeborn" is a term associated with political agitator John Lilburne (1614–1657), a member of the Levellers, a 17th-century English political party. As a word, "freeborn" means born free, rather than in slavery or bondage or vassalage. Lilbu ...

sons and daughters who, unlike their freed parents, were Roman citizens by birth. The child's

tria nomina

Over the course of some fourteen centuries, the Romans and other peoples of Italy employed a system of nomenclature that differed from that used by other cultures of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea, consisting of a combination of personal and fa ...

, which served to show that the child was dignified and truly Roman, was typically inscribed upon the tombstone.

Infants additionally had one or two

epithets inscribed upon the stone that emphasized the moral aspects of the child's life. These epithets served to express the fact that even young children were governed by

Roman virtues.

Social elite

Members of the ruling class became interested in erecting funerary monuments during the Augustan-Tiberian period. Yet, by and large, this interest was brief. Whereas freedmen were often compelled to display their success and social mobility through the erection of public monuments, the elite felt little need for an open demonstration of this kind.

Archeological findings in

Pompeii suggest that tombs and monuments erected by freedmen increased at the very moment when those erected by the elite began to decrease.

This change in custom signifies a restoration of pre-Augustan minimalism and austerity among the aristocracy in Rome.

Self-remembrance among the social elite became uncommon during this time. Nonetheless governed by a strong sense of duty and religious piety, however, ancient Romans chose to celebrate the dead privately. With this change, noble or aristocratic families took to commemorating the deceased by adding inscriptions or simple headstones to existing burial sites.

These sites, which were often located on the family's country estate, offered privacy to a grieving household.

Unlike freedmen, the Roman elite rarely used tombstones or other funerary monuments as indicators of social status. The size and style of one's

cippi

A (plural: ''cippi''; "pointed pole") is a low, round or rectangular pedestal set up by the Ancient Romans for purposes such as a milestone or a boundary post. They were also used for somewhat differing purposes by the Etruscans and Carthaginians ...

, for example, was largely a personal choice and not something influenced by the need to fulfill greater social obligations.

Soldiers

In a military context, burial sites served to honor fallen soldiers as well as to mark newly sequestered Roman territory, such as

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

. The most common funerary monument for Roman soldiers was that of the

stele – a humble, unadorned piece of stone, cut into the shape of a rectangle.

The name, rank, and unit of the deceased would be inscribed upon the stone, as well as his age and his years of service in the

Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

.

The name of the commemorator, usually an heir or close family member, could be inscribed near the bottom of the stele if desired.

Uniform in nature, the consistent style of these tombstones reflected the orderly, systematic nature of the army itself.

Each tombstone stood as a testament to the strength and persistence of the Roman army as well as the individual soldiers.

In some unique cases, military tombstones were adorned with sculpture. These types of headstones typically belonged to members of the

auxiliary units rather than

legionary units.

The chief difference between the two units was citizenship.

Whereas legionary soldiers were citizens of Rome, auxiliary soldiers came from provinces in the Empire. Auxiliary soldiers had the opportunity to obtain

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

only after their discharge.

Tombstones served to distinguish Romans from non-romans, and to enforce the social-hierarchy that existed within military legions.

For men who died in battle, the erection of ornate tombstones was a final attempt at Romanization. Reliefs on auxiliary tombstones often depict men on horseback, denoting the courage and heroism of the auxiliary's

cavalrymen

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

. Though expensive, tombstones were likely within the means of the common soldier.

Unlike most lower class citizens in ancient Rome, soldiers received a regular income.

Moreover, some historians suggest the creation of a burial club, a group organized to collect regular monetary contributions from the legions.

The proceeds served to subsidize the cost of burial for fallen soldiers.

Countless soldiers died in times of Roman war. Tombstones, therefore, were a way to identify and honor one's military service and personal achievement on the battlefield.

These tombstones did not commemorate soldiers who died in combat, but rather soldiers who died during times of peace when generals and comrades were at ease to hold proper burials.

Soldiers who died in battle were disrobed, cremated, and buried in mass graves near camp.

In some cases, heirs or other family members commissioned the construction of

cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

s for lost soldiers – funerary monuments that commemorated the dead as if the body had been found and returned home.

See also

*

Death in ancient Greek art

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Description of the reconstruction of a Roman sarcophagus in theJ. Paul Getty Museum

The J. Paul Getty Museum, commonly referred to as the Getty, is an art museum in Los Angeles, California housed on two campuses: the Getty Center and Getty Villa.

The Getty Center is located in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles and fea ...

{{Roman art

Ancient Roman art

Funerary art

Roman funerary art changed throughout the course of the

Roman funerary art changed throughout the course of the

Also present was an influence from the lands east of Greece. Although the architectural contributions of