Roman Catholic Archdiocese Of Wrocław on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Archdiocese of Wrocław (; ; ; ) is a

In the election of Henry of Wierzbna (1302–19), the German party in the cathedral chapter won, but this victory cost the new bishop the enmity of the opposing faction. He was made guardian of the youthful Dukes of Wrocław, and this appointment, together with the factional disputes, led to the bringing of grave accusations against him. The researches of more recent times have proved the groundlessness of these attacks. He was kept in

In the election of Henry of Wierzbna (1302–19), the German party in the cathedral chapter won, but this victory cost the new bishop the enmity of the opposing faction. He was made guardian of the youthful Dukes of Wrocław, and this appointment, together with the factional disputes, led to the bringing of grave accusations against him. The researches of more recent times have proved the groundlessness of these attacks. He was kept in

Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) was elected bishop while pursuing his studies at

Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) was elected bishop while pursuing his studies at  Konrad's successor was the provost of the cathedral of Wrocław, Peter II Nowak (1447–56). By wise economy Bishop Peter succeeded in bringing the diocesan finances into a better condition and in redeeming the greater part of the church lands which his predecessor had been obliged to mortgage. At the diocesan synod of 1454 he endeavoured to suppress the abuses that had arisen in the diocese.

Jošt of Rožmberk (1456–67) was a

Konrad's successor was the provost of the cathedral of Wrocław, Peter II Nowak (1447–56). By wise economy Bishop Peter succeeded in bringing the diocesan finances into a better condition and in redeeming the greater part of the church lands which his predecessor had been obliged to mortgage. At the diocesan synod of 1454 he endeavoured to suppress the abuses that had arisen in the diocese.

Jošt of Rožmberk (1456–67) was a  As coadjutor, he had selected a Swabian, Johann IV Roth, Bishop of Lavant, a man of humanistic training. Urged by King

As coadjutor, he had selected a Swabian, Johann IV Roth, Bishop of Lavant, a man of humanistic training. Urged by King  His successor, Andreas von Jerin (1585–96), a Swabian who had educated at the German College at Rome, followed in his footsteps. At the diocesan synod of 1592 he endeavoured to improve church discipline. Besides his zeal in elevating the life of the Church, he was also a promoter of the arts and learning. The silver altar with which he adorned his cathedral still exists, and he brought the schools in the principality of Neisse into a flourishing condition. The bishop also rendered important services to the emperor, as

His successor, Andreas von Jerin (1585–96), a Swabian who had educated at the German College at Rome, followed in his footsteps. At the diocesan synod of 1592 he endeavoured to improve church discipline. Besides his zeal in elevating the life of the Church, he was also a promoter of the arts and learning. The silver altar with which he adorned his cathedral still exists, and he brought the schools in the principality of Neisse into a flourishing condition. The bishop also rendered important services to the emperor, as  In July 1619 Czech Protestants rebelled against King Ferdinand II and offered the Bohemian crown to Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate. On 27 September 1619, probably on hearing the news, Władysław and Charles left Silesia in a hurry and on 7 October 1619 arrived in Warsaw. In December 1619, young Władysław's brother, Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Opole, was chosen by Charles as auxiliary bishop of Wrocław, which was confirmed by the Polish episcopate. The Battle of the White Mountain (1620) broke the revolt in Bohemian Crown (i.e. including the opposition of the Protestants of Silesia). The Bishopric of Breslau (Wrocław) returned to the rule of the Archbishopric of Gniezno in 1620, having before been practically independent. Bishop Charles began the restoration of the principality of Neisse (Nysa) to the Catholic faith. The work was completed by his successor, Charles Ferdinand, Prince of Poland (1625–55), who spent most of his time in his own country, but appointed excellent administrators for the diocese, such as the Coadjutor-Bishop Liesch von Hornau, and Archdeacon Gebauer. Imperial commissioners gave back to the Catholic Church those church buildings in the chief places of the principalities which had become the property of the sovereign through the extinction of vassal families. Until 1632 ''de facto'' rule was held in Warsaw by King Sigismund III and not by the bishop or archbishop.

According to the terms of the 1648

In July 1619 Czech Protestants rebelled against King Ferdinand II and offered the Bohemian crown to Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate. On 27 September 1619, probably on hearing the news, Władysław and Charles left Silesia in a hurry and on 7 October 1619 arrived in Warsaw. In December 1619, young Władysław's brother, Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Opole, was chosen by Charles as auxiliary bishop of Wrocław, which was confirmed by the Polish episcopate. The Battle of the White Mountain (1620) broke the revolt in Bohemian Crown (i.e. including the opposition of the Protestants of Silesia). The Bishopric of Breslau (Wrocław) returned to the rule of the Archbishopric of Gniezno in 1620, having before been practically independent. Bishop Charles began the restoration of the principality of Neisse (Nysa) to the Catholic faith. The work was completed by his successor, Charles Ferdinand, Prince of Poland (1625–55), who spent most of his time in his own country, but appointed excellent administrators for the diocese, such as the Coadjutor-Bishop Liesch von Hornau, and Archdeacon Gebauer. Imperial commissioners gave back to the Catholic Church those church buildings in the chief places of the principalities which had become the property of the sovereign through the extinction of vassal families. Until 1632 ''de facto'' rule was held in Warsaw by King Sigismund III and not by the bishop or archbishop.

According to the terms of the 1648  Frederick of Hesse-Darmstadt, Cardinal and

Frederick of Hesse-Darmstadt, Cardinal and

The next prince-bishop, Philip, Count von Sinzendorf, Cardinal and

The next prince-bishop, Philip, Count von Sinzendorf, Cardinal and  The dean of the cathedral, Dr. Ritter, administered the diocese for several years until the election of Joseph Knauer (1843–44), earlier Grand Dean of the Silesian County of Glatz within the Diocese of Hradec Králové. The new prince-bishop, who was 79 years old, lived only a year after his appointment.

His successor was Melchior, Freiherr von Diepenbrock (1845–53). This episcopate was the beginning of a new religious and ecclesiastical life in the diocese. During the revolutionary period the prince-bishop not only maintained order in his see, which was in a state of ferment, but was also a supporter of the government. He received unusual honours from the king and was made a cardinal by the Pope. He died 20 January 1853, at the Johannisberg (

The dean of the cathedral, Dr. Ritter, administered the diocese for several years until the election of Joseph Knauer (1843–44), earlier Grand Dean of the Silesian County of Glatz within the Diocese of Hradec Králové. The new prince-bishop, who was 79 years old, lived only a year after his appointment.

His successor was Melchior, Freiherr von Diepenbrock (1845–53). This episcopate was the beginning of a new religious and ecclesiastical life in the diocese. During the revolutionary period the prince-bishop not only maintained order in his see, which was in a state of ferment, but was also a supporter of the government. He received unusual honours from the king and was made a cardinal by the Pope. He died 20 January 1853, at the Johannisberg (

Latin Church

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous () particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 Catholic particular churches and liturgical ...

ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

centered in the city of Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. From its founding as a bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

in 1000 until 1821, it was under the Archbishopric of Gniezno

The Archdiocese of Gniezno (, ) is the oldest Latin Catholic archdiocese in Poland, located in the city of Gniezno.

in Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

. From 1821 to 1930 it was subjected directly to the Apostolic See

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism, the phrase "The Apostolic See" when capitalized refers specifically to the See of ...

. Between 1821 and 1972 it was officially known as (Arch)Diocese of Breslau.

History

Medieval era (within Poland)

Christianity was first introduced intoSilesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

by missionaries from Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

. After the conversion of Duke Mieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was Duchy of Poland (966–1025), Duke of Poland from 960 until his death in 992 and the founder of the first unified History of Poland, Polish state, the Civitas Schinesghe. A member of the Piast dynasty, he was t ...

of Poland and the conquest of Silesia, the work of bringing the people to the new faith went on more rapidly. Up to about the year 1000 Silesia had no bishop of its own, but was united with neighbouring dioceses. The upper part of the Oder River

The Oder ( ; Czech and ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and its largest tributary the Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows through west ...

formed the boundary of the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavs, West Slavic tribe of Polans (western), Polans who lived in what i ...

. All the territory which is now Silesia – lying on the right-hand bank of the Oder – belonged, therefore, to the Diocese of Poznań, which was suffragan

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Catholic Church, a suffragan bishop leads a diocese within an ecclesiastical province other than the principal diocese, the metropolitan archdiocese; the diocese led ...

to the Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was a Catholic Church, Latin Catholic archdiocese (969–1552) and Prince-Bishopric, Prince-Archbishopric (1180–1680) of the Holy Roman Empire centered on the city of Magdeburg on the Elbe River.

Planned since 95 ...

. This part of Silesia was thus under the jurisdiction of a priest named Jordan who was appointed first Bishop of Poznań in 968. The part of Silesia lying on the left bank of the Oder belonged to the territory included in then Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

, and was consequently within the diocesan jurisdiction of Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. The Bishopric of Prague, founded in 973, was suffragan to the Archbishopric of Mainz

The Electorate of Mainz ( or '; ), previously known in English as Mentz and by its French name Mayence, was one of the most prestigious and influential states of the Holy Roman Empire. In the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the Archbishop-Elec ...

.

Duke Bolesław I the Brave

Bolesław I the Brave (17 June 1025), less often List of people known as the Great, known as Bolesław the Great, was Duke of Poland from 992 to 1025 and the first King of Poland in 1025. He was also Duke of Bohemia between 1003 and 1004 as Boles ...

, the son of Mieszko, obtained the Bohemian part of Silesia during his wars of conquest, and a change in the ecclesiastical dependence of the province followed. By a patent of Emperor Otto III

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was the Holy Roman emperor and King of Italy from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

Otto III was c ...

in 995, Silesia was attached to the Bishopric of Meissen, which, like Poznań, was suffragan to the Archbishopric of Magdeburg. Soon after, Bolesław, who ruled all of Silesia, and emperor Otto, to whom Bolesław had pledged allegiance, founded the Diocese of Wrocław, which, together with the Bishoprics of Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg (; ; ) is a port and spa city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast of the Baltic Sea (in the middle of the section ...

, was placed under the Archbishopric of Gniezno

The Archdiocese of Gniezno (, ) is the oldest Latin Catholic archdiocese in Poland, located in the city of Gniezno.

in Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

, founded by Otto in 1000 during the Congress of Gniezno. The first Bishop of Wrocław is said to have been named Jan, but nothing more than this is known of him, nor is there extant any official document giving the boundaries of the diocese at the time of its erection. However, they are defined in the Bulls of approval and protection issued by Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian (or Hadrian) IV (; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 until his death in 1159. Born in England, Adrian IV was the first Pope ...

, 23 April 1155, and by Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV (; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universities of Parma and Bolo ...

, 9 August 1245.

The powerful Polish ruler Bolesław I was succeeded by his son Mieszko II Lambert

Mieszko II Lambert (; c. 990 – 10/11 May 1034) was List of Polish monarchs, King of Kingdom of Poland (1025–1031), Poland from 1025 to 1031 and Duchy of Poland (c. 960–1025), Duke from 1032 until his death.

He was the second son of Boles� ...

, who had but a short reign. After his death a revolt against Christianity and the reigning family broke out, the new Church organization of Poland disappeared from view, and the names of the Bishops of Wrocław for the next half century are unknown. Casimir I, the son of Mieszko, and his mother were driven out of the country, but through German aid they returned and the affairs of the Church were brought into better order. A Bishop of Wrocław from probably 1051 to 1062 was Hieronymus, said by later tradition to have been a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

nobleman. He was followed by John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

(1062–72), who was succeeded by Piotr I (1071–1111). During the episcopate of Piotr I, Count Piotr Włostowic entered upon the work of founding churches and monasteries which has preserved his name. Petrus was followed by: Żyrosław I (1112–20); Heymo (1120–26), who welcomed Otto of Bamberg to Wrocław in May 1124 when the saint was on his missionary journey to Pomerania; Robert I (1127–42), who was Bishop of Kraków

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

; Robert II (1142–46); and Janik (1146–49), who became Archbishop of Gniezno.

With the episcopate of Bishop Walter

Walter may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Walter (name), including a list of people and fictional and mythical characters with the given name or surname

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–19 ...

(1149–69) the history of the diocese of Wrocław begins to grow clearer. Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian (or Hadrian) IV (; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 until his death in 1159. Born in England, Adrian IV was the first Pope ...

, at Walter's request in 1155, took the bishopric under his protection and confirmed to it the territorial possessions of which a list had been submitted to him. Among the rights which the Pope then confirmed was that of jurisdiction over the lands belonging to the castle of Otmuchów

Otmuchów (pronounced: ; ) is a town in Nysa County, Opole Voivodeship, in southern Poland, with 6,581 inhabitants (2019).

Etymology

The city was mentioned for the first time as ''Otemochow'' in 1155. It was named in its Old Polish form ''Othmucho ...

, which had been regarded as the patrimony of the diocese from its foundation. In 1163 the sons of the exiled Polish duke Władysław returned from the Empire and, through the intervention of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

, received as an independent duchy the part of Silesia which was included at that date in the see of Wrocław. Bishop Walter built a new, massively constructed cathedral, in which he was buried. Żyrosław II (1170–98) encouraged the founding of the Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

monastery of Lubusz by Duke Bolesław I the Tall

Bolesław I the Tall (; 1127 – 7 or 8 December 1201) was Duke of Wrocław from 1163 until his death in 1201.

Early years

Boleslaw was the eldest son of Władysław II the Exile by his wife Agnes of Babenberg, daughter of Margrave Leopold II ...

. In 1180 Żyrosław took part in the national assembly at Łęczyca

Łęczyca (; in full the Royal Town of Łęczyca, ; ; ) is a town of inhabitants in central Poland. Situated in the Łódź Voivodeship, it is the county seat of the Łęczyca County. Łęczyca is a capital of the historical Łęczyca Land.

Or ...

at which laws for the protection of the Church and its property were promulgated. Jarosław

Jarosław (; , ; ; ) is a town in southeastern Poland, situated on the San (river), San River. The town had 35,475 inhabitants in 2023. It is the capital of Jarosław County in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship.

History

Jarosław is located in the ...

(1198–1201), the oldest son of Duke Bolesław, and Duke of Opole

Opole (; ; ; ) is a city located in southern Poland on the Oder River and the historical capital of Upper Silesia. With a population of approximately 127,387 as of the 2021 census, it is the capital of Opole Voivodeship (province) and the seat of ...

, was the first prince to become Bishop of Wrocław (see prince-bishop

A prince-bishop is a bishop who is also the civil ruler of some secular principality and sovereignty, as opposed to '' Prince of the Church'' itself, a title associated with cardinals. Since 1951, the sole extant prince-bishop has been the ...

).

Cyprian (1201–7) was originally Abbot of the Premonstratensian

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular in the Catholic Chur ...

monastery of St. Vincent near Wrocław, then Bishop of Lubusz, and afterwards Bishop of Wrocław. During Cyprian's episcopate Duke Heinrich I and his wife, St. Hedwig, founded the Cistercian convent at Trzebnica. The episcopate of Bishop Wawrzyniec (1207–32) was marked by his efforts to bring colonies of Germans into the church territories, to effect the cultivation of waste lands. This introduction of German settlers by the bishop was in accordance with the example set by Duke Henry the Bearded and Duchess consort St. Hedwig. The monasteries of the Augustinian Canons

The Canons Regular of St. Augustine are Catholic priests who live in community under a rule ( and κανών, ''kanon'', in Greek) and are generally organised into religious orders, differing from both secular canons and other forms of religio ...

, Premonstratensians

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in United Kingdom, Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their religious habit, habit), is a religious order of cano ...

and Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

s took an active part in carrying out the schemes of the rulers by placing great numbers of Germans, especially Thuringians

The Thuringii, or Thuringians were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who lived in the kingdom of the Thuringians that appeared during the late Migration Period south of the Harz Mountains of central Germania, a region still known today as Thur ...

and Franconia

Franconia ( ; ; ) is a geographical region of Germany, characterised by its culture and East Franconian dialect (). Franconia is made up of the three (governmental districts) of Lower Franconia, Lower, Middle Franconia, Middle and Upper Franco ...

ns, on the large estates that had been granted them.

One of the most noted bishops of the diocese, Tomasz I (1232–68), continued the work of German colonization with so much energy that even the first Mongol invasion of Poland

The Mongol invasion of Poland from late 1240 to 1241 culminated in the Battle of Legnica, where the Mongols defeated an alliance which included forces from Testament of Bolesław III Wrymouth, fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry ...

(1241) made but a temporary break in the process. As German colonization in Silesia increased, the city of Wrocław began to be also known by the Germanized name of Breslau, leading to the diocese also becoming called the Bishopric of Breslau. Tomasz's defence of the rights of the Church involved him in bitter conflicts with Duke Bolesław II the Horned. Tomasz began the construction of the present cathedral, the chancel being the first part erected. St. Hedwig died during his episcopate; and he lived until the process of her canonization was completed, but died before the final solemnity of her elevation to the altars of the Catholic Church. After Tomasz I, Ladislaus, a grandson of Saint Hedwig, and Archbishop of Salzburg

The Archdiocese of Salzburg (; ) is a Latin Church, Latin rite archdiocese of the Catholic Church centered in Salzburg, Austria. It is also the principal diocese of the ecclesiastical province of Salzburg. The archdiocese is one of two Austrian ...

, was Administrator of the Diocese of Wrocław until his death in 1270.

He was followed by Tomasz II Zaremba (1270–92), who was involved for years in a violent dispute with Duke Henryk IV Probus as to the prerogatives of the Church in Silesia. In 1287 a reconciliation was effected between them at Regensburg

Regensburg (historically known in English as Ratisbon) is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the rivers Danube, Naab and Regen (river), Regen, Danube's northernmost point. It is the capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the ...

, and in 1288 the duke founded the collegiate church of the Holy Cross at Wrocław. Before his death, on the Eve of St. John in 1290, the duke confirmed the rights of the Church to sovereignty over the territories of Nysa and Otmuchów. Tomasz II consecrated the high altar of the cathedral; he was present at the First Council of Lyon (1274) and in 1279 held a diocesan synod. Jan III Romka (1292–1301), belonged to the Polish party in the cathedral chapter

According to both Catholic and Anglican canon law, a cathedral chapter is a college of clerics ( chapter) formed to advise a bishop and, in the case of a vacancy of the episcopal see in some countries, to govern the diocese during the vacancy. In ...

. His maintenance of the prerogatives of the Church brought him, also, into conflict with the temporal rulers of Silesia; in 1296 he called a synod for the defence of these rights.

Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

a number of years by a suit before the Curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

which was finally settled in his favour. Notwithstanding the troubles of his life he was energetic in the performance of his duties. He carried on the construction of the cathedral, and in 1305 and 1316 held diocesan synods. The office of Auxiliary Bishop

An auxiliary bishop is a bishop assigned to assist the diocesan bishop in meeting the pastoral and administrative needs of the diocese. Auxiliary bishops can also be titular bishops of sees that no longer exist as territorial jurisdictions.

...

of Wrocław dates from his episcopate. After his death a divided vote led to a vacancy of the see. The two candidates, Wit and Lutold, elected by the opposing factions, finally resigned, and Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Papacy, Avignon Pope, elected by ...

transferred Nanker of Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

to Wrocław (1326–41).

Within Bohemia and the Habsburg Monarchy

The constant division and subdivision of Silesian territory into small principalities for the members of the ruling families resulted in a condition of weakness that resulted in dependence on a stronger neighbour, and parts of Silesia thus came under the control of Bohemia (first between 1289 and 1306; definitely from 1327 onwards), which itself was part of theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. A quarrel broke out between Bishop Nanker and the suzerain of Silesia, King John I of Bohemia

John of Bohemia, also called the Blind or of Luxembourg (; ; ; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of Poland. He is well known for having died while fighting ...

, when the king seized the castle of Milicz which belonged to the cathedral chapter. The bishop excommunicated the king and those members of the Council of Wrocław who sided with him. On account of this he was obliged to flee from Breslau and take refuge in Nysa, where he died.

Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) was elected bishop while pursuing his studies at

Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) was elected bishop while pursuing his studies at Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, and was consecrated bishop at Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

. Through his friendship with Charles, the son of King John, he was soon able to settle the discord that had arisen under his predecessor. The diocese prospered greatly under his rule. He bought the Duchy of Grodków from Duke Bolesław III the Generous

Bolesław or Boleslav may refer to:

People

* Bolesław (given name) (also ''Boleslav'' or ''Boleslaus''), including a list of people with this name

Geography

* Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

* Bolesław, Olkusz Coun ...

and added it to the episcopal territory of Nysa. The Bishops of Wrocław had, therefore, after this the titles of Prince of Nysa and Duke of Grodków, and took precedence over the other Silesian rulers who held principalities in fief.

Emperor Charles IV wished to separate Wrocław from the Archdiocese of Gniezno and to make it a suffragan of the newly erected Archbishopric of Prague (1344) but the plan failed, owing to the opposition of the Archbishop of Gniezno. Przecław added to the cathedral the beautiful Lady Chapel, in which he was buried and where his tomb still exists. Dietrich, dean of the cathedral, who was elected as successor to Przecław, could not obtain the papal confirmation, and the Bishop of Olomouc, who was chosen in his place, soon died. After a long contest with Charles, Bishop Wenceslaus of Lebus, Duke of Legnica

Legnica (; , ; ; ) is a city in southwestern Poland, in the central part of Lower Silesia, on the Kaczawa River and the Czarna Woda. As well as being the seat of the county, since 1992 the city has been the seat of the Diocese of Legnica. Le ...

, was transferred to Wrocław (1382–1417). The new bishop devoted himself to repairing the damage inflicted on the Church in Silesia by the actions of Charles. He held two synods, in 1410 and 1415, with the object of securing a higher standard of ecclesiastical discipline; and he settled the right of inheritance in the territory under his dominion by promulgating the church decree called "Wenceslaus' law". Resigning his bishopric in 1417, Wenceslaus died in 1419.

The episcopate of Konrad IV the Elder, Duke of Oleśnica, the next bishop (1417–47), was a trying time for Silesia during the Hussite wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, a ...

. Konrad was placed at the head of the Silesian confederation formed to defend the country against hostile incursions. In 1435 the bishop issued a decree of which the chief intent was to close the prebends in the diocese of Wrocław to "foreigners", and thus prevent the Poles from obtaining these offices. The effort to shut out the Polish element and to loosen the connection with Gniezno

Gniezno (; ; ) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. The city is the administrative seat of Gniezno County (''powiat'') ...

was not a momentary one; it continued, and led gradually to a virtual separation from the Polish archdiocese some time before the formal separation took place. The troubles of the times brought the bishop and the diocese into serious pecuniary difficulties, and in 1444 Konrad resigned, but his resignation was not accepted and he resumed his office. In 1446 he held a diocesan synod and died in the following year.

Konrad's successor was the provost of the cathedral of Wrocław, Peter II Nowak (1447–56). By wise economy Bishop Peter succeeded in bringing the diocesan finances into a better condition and in redeeming the greater part of the church lands which his predecessor had been obliged to mortgage. At the diocesan synod of 1454 he endeavoured to suppress the abuses that had arisen in the diocese.

Jošt of Rožmberk (1456–67) was a

Konrad's successor was the provost of the cathedral of Wrocław, Peter II Nowak (1447–56). By wise economy Bishop Peter succeeded in bringing the diocesan finances into a better condition and in redeeming the greater part of the church lands which his predecessor had been obliged to mortgage. At the diocesan synod of 1454 he endeavoured to suppress the abuses that had arisen in the diocese.

Jošt of Rožmberk (1456–67) was a Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

nobleman and Grand Prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be lowe ...

of the Knights of St. John. His love of peace made his position a very difficult one during the fierce ecclesiastic-political contention that raged between the Hussite

file:Hussitenkriege.tif, upright=1.2, Battle between Hussites (left) and Crusades#Campaigns against heretics and schismatics, Catholic crusaders in the 15th century

file:The Bohemian Realm during the Hussite Wars.png, upright=1.2, The Lands of the ...

King of Bohemia, George of Poděbrady

George of Kunštát and Poděbrady (23 April 1420 – 22 March 1471), also known as Poděbrad or Podiebrad (; ), was the sixteenth King of Bohemia, who ruled in 1458–1471. He was a leader of the Hussites, but moderate and tolerant toward the ...

, and the people of Breslau, who had taken sides with the German party. Jodokus was followed by a bishop from the region of the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

, Rudolf of Rüdesheim (1468–82). As papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, Rudolf had become popular in Breslau through his energetic opposition to George of Podebrady; for this reason the cathedral chapter requested his transfer from the small Diocese of Lavant in Carinthia

Carinthia ( ; ; ) is the southernmost and least densely populated States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The Lake Wolayer is a mountain lake on the Carinthian side of the Carnic Main ...

, after he had confirmed their privileges. From this time these privileges were called "the Rudolfian statutes". Under his leadership the party opposed to Podebrady obtained the victory, and Rudolf proceeded at once to repair the damage which had been occasioned to the Church during this strife; mortgaged church lands were redeemed; in 1473 and 1475 diocesan synods were held, at which the bishop took active measures in regard to church discipline.

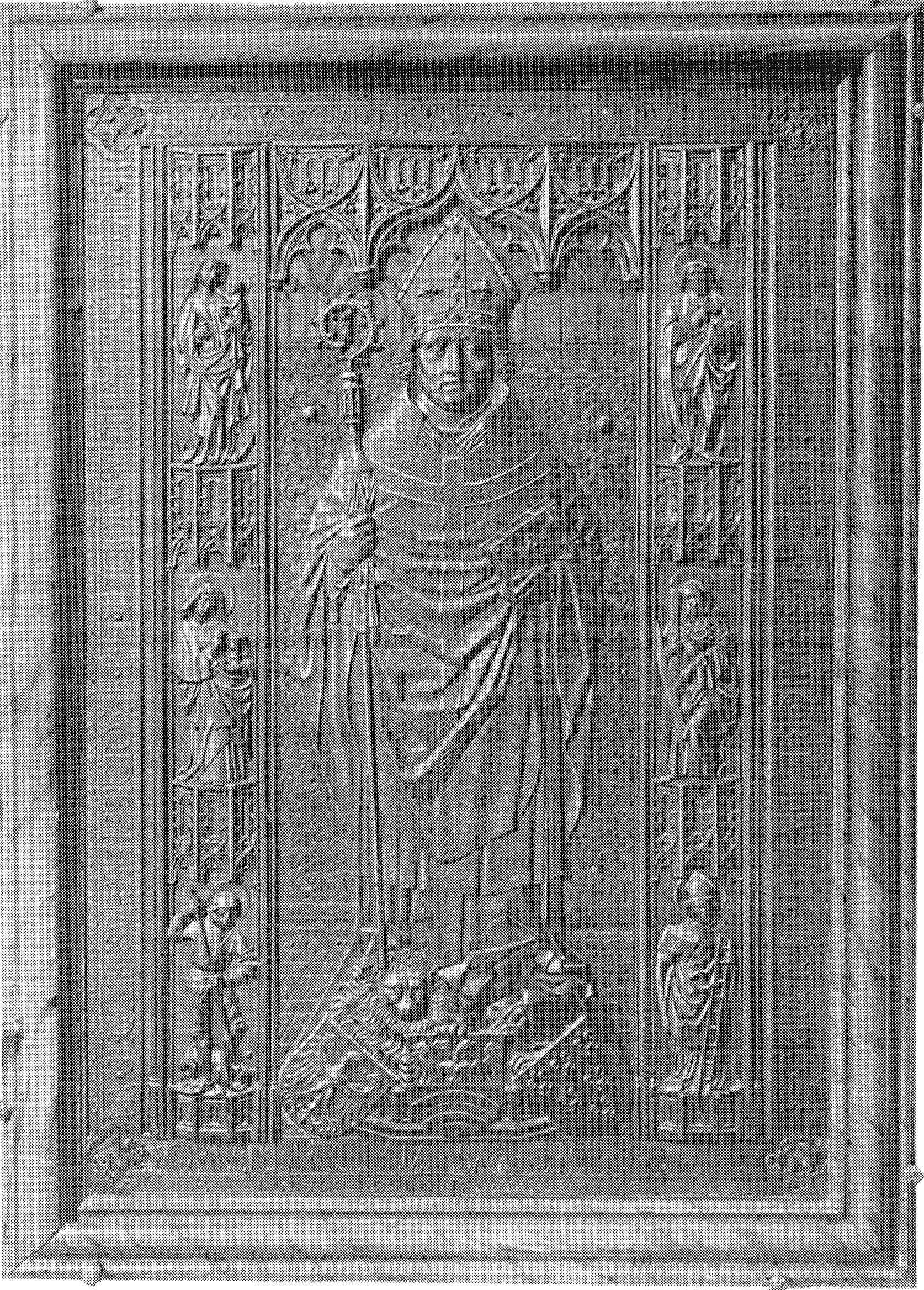

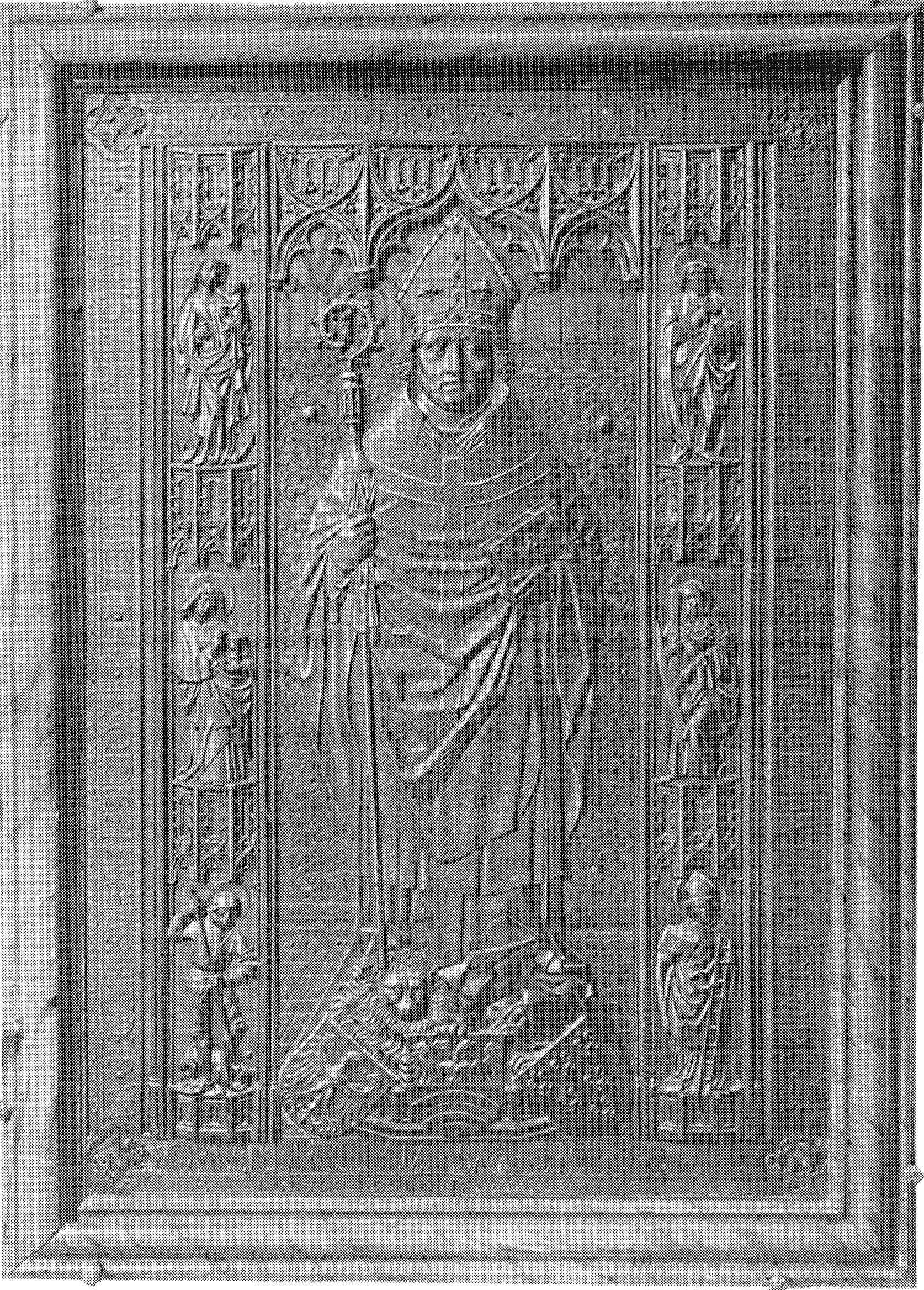

As coadjutor, he had selected a Swabian, Johann IV Roth, Bishop of Lavant, a man of humanistic training. Urged by King

As coadjutor, he had selected a Swabian, Johann IV Roth, Bishop of Lavant, a man of humanistic training. Urged by King Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus (; ; ; ; ; ) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia from 1458 to 1490, as Matthias I. He is often given the epithet "the Just". After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected King of Bohemia in 1469 and ...

of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, to whom Silesia was then subject, the cathedral chapter, somewhat unwillingly, chose the coadjutor as bishop (1482–1506). His episcopate was marked by violent quarrels with the cathedral chapter. But at the same time he was a promoter of art and learning, and strict in his conception of church rights and duties. He endeavoured to improve the spiritual life of the diocese by holding a number of synods. Before he died the famous worker in bronze, Peter Vischer of Nuremberg, cast his monument, the most beautiful bishop's tomb in Silesia. His coadjutor with right of succession was John V Thurzó (1506–20), a member of the noble Hungarian family of Thurzó. John V took an active part in the intellectual life of the time and sought at the diocesan synods to promote learning and church discipline, and to improve the schools. On the ruins of the old stronghold of Javorník he built the Jánský Vrch

Jánský Vrch () is a castle located in the Jeseník District in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. The castle stands on a hill above the town of Javorník in the north-western edge of Czech Silesia, in area what was a part of the Duchy ...

castle, later the summer residence of the Prince-Bishop of Breslau.

The religious disturbances of the 16th century began to be conspicuously apparent during this episcopate, and soon after John's death Protestantism began to spread in Silesia, which belonged to the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

since 1526. Princes, nobles, and town councils were zealous promoters of the new belief; even in the episcopal principality of Neisse (Nysa)-Grottkau (Grodków) Protestant doctrines found approval and acceptance. The successors of John V were partly responsible for this condition of affairs. Jacob von Salza (1520–39) was personally a stanch adherent of the Church; yet the gentleness of his disposition caused him to shrink from carrying on a war against the powerful religious movement that had arisen. To an even greater degree than Jacob von Salza his successor, Balthasar von Promnitz (1539–63), avoided coming into conflict with Protestantism. He was more friendly in his attitude to the new doctrine than any other Bishop of Breslau. Casper von Logau (1562–74) showed at first greater energy than his predecessor in endeavouring to compose the troubles of his distracted diocese, but later in his episcopate his attitude towards Lutheranism and his slackness in defending church rights gave great offence to those who had remained true to the Faith. These circumstances make the advance of Protestantism easy to understand. At the same time it must be remembered that the bishops, although also secular rulers, had a difficult position in regard to spiritual matters. At the assemblies of the nobles and at the meetings of the diet, the bishops and the deputies of the cathedral chapter were, as a rule, the only Catholics against a large and powerful majority on the side of Protestantism. The Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

suzerains, who lived far from Silesia (in Vienna or Prague), and who were constantly preoccupied by the danger of a Turkish invasion, were not in a position to enforce the edicts which they issued for the protection of the Church.

The Silesian clergy had in great measure lost their high concept of the priestly office, although there were honourable exceptions. Among those faithful were the majority of the canons of the cathedral of Breslau; they distinguished themselves not only by their learning, but also by their religious zeal. It was in the main due to them that the diocese did not fall into spiritual ruin. The chapter was the willing assistant of the bishops in the reform of the diocese. Martin of Gerstmann (1574–85) began the renovation of the diocese, and the special means by which he hoped to attain the desired end were: the founding of a seminary for clerics, visitations of the diocese, diocesan synods, and the introduction of the Jesuits.

His successor, Andreas von Jerin (1585–96), a Swabian who had educated at the German College at Rome, followed in his footsteps. At the diocesan synod of 1592 he endeavoured to improve church discipline. Besides his zeal in elevating the life of the Church, he was also a promoter of the arts and learning. The silver altar with which he adorned his cathedral still exists, and he brought the schools in the principality of Neisse into a flourishing condition. The bishop also rendered important services to the emperor, as

His successor, Andreas von Jerin (1585–96), a Swabian who had educated at the German College at Rome, followed in his footsteps. At the diocesan synod of 1592 he endeavoured to improve church discipline. Besides his zeal in elevating the life of the Church, he was also a promoter of the arts and learning. The silver altar with which he adorned his cathedral still exists, and he brought the schools in the principality of Neisse into a flourishing condition. The bishop also rendered important services to the emperor, as legate

Legate may refer to: People

* Bartholomew Legate (1575–1611), English martyr

* Julie Anne Legate (born 1972), Canadian linguistics professor

* William LeGate (born 1994), American entrepreneur

Political and religious offices

*Legatus, a hig ...

at various times.

Bonaventura Hahn, elected in 1596 as the successor of Andreas von Jerin, was not recognized by the emperor and was obliged to resign his position. The candidate of the emperor, Paul Albert (1599–1600), occupied the see only one year. Johann VI (1600–8), a member of a noble family of Silesia named von Sitsch, took more severe measures than his predecessors against Protestantism, in the hope of checking it, especially in the episcopal principality of Neisse-Grottkau.

Bishop Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

(1608–24), an Archduke of Austria, had greater success than his predecessor after the first period of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

had taken a turn favourable to Austria and the Catholic party. Charles wanted to move under protection of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, hoping to avoid participation in the war which was ravaging the Holy Roman Empire. As Charles's bishopric was nominally subordinated to the Polish Archbishopric of Gniezno, he asked the Archbishop of Gniezno for mediation in talks with King Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Re ...

of Poland about protection and subordination of his bishopric. In May 1619, Prince Władysław (the future King Władysław IV Vasa

Władysław IV Vasa or Ladislaus IV (9 June 1595 – 20 May 1648) was King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania and claimant of the thrones of Monarchy of Sweden, Sweden and List of Russian monarchs, Russia. Born into the House of Vasa as a prince ...

), invited by his uncle Charles, left Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

and started a trip to Silesia. During talks with Władysław in mid-1619, the Habsburgs promised to agree to a temporary occupation of part of Silesia by Polish forces, which the unsuccessfully Vasas hoped would later allow the re-incorporation of those areas into Poland.

In July 1619 Czech Protestants rebelled against King Ferdinand II and offered the Bohemian crown to Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate. On 27 September 1619, probably on hearing the news, Władysław and Charles left Silesia in a hurry and on 7 October 1619 arrived in Warsaw. In December 1619, young Władysław's brother, Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Opole, was chosen by Charles as auxiliary bishop of Wrocław, which was confirmed by the Polish episcopate. The Battle of the White Mountain (1620) broke the revolt in Bohemian Crown (i.e. including the opposition of the Protestants of Silesia). The Bishopric of Breslau (Wrocław) returned to the rule of the Archbishopric of Gniezno in 1620, having before been practically independent. Bishop Charles began the restoration of the principality of Neisse (Nysa) to the Catholic faith. The work was completed by his successor, Charles Ferdinand, Prince of Poland (1625–55), who spent most of his time in his own country, but appointed excellent administrators for the diocese, such as the Coadjutor-Bishop Liesch von Hornau, and Archdeacon Gebauer. Imperial commissioners gave back to the Catholic Church those church buildings in the chief places of the principalities which had become the property of the sovereign through the extinction of vassal families. Until 1632 ''de facto'' rule was held in Warsaw by King Sigismund III and not by the bishop or archbishop.

According to the terms of the 1648

In July 1619 Czech Protestants rebelled against King Ferdinand II and offered the Bohemian crown to Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate. On 27 September 1619, probably on hearing the news, Władysław and Charles left Silesia in a hurry and on 7 October 1619 arrived in Warsaw. In December 1619, young Władysław's brother, Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Opole, was chosen by Charles as auxiliary bishop of Wrocław, which was confirmed by the Polish episcopate. The Battle of the White Mountain (1620) broke the revolt in Bohemian Crown (i.e. including the opposition of the Protestants of Silesia). The Bishopric of Breslau (Wrocław) returned to the rule of the Archbishopric of Gniezno in 1620, having before been practically independent. Bishop Charles began the restoration of the principality of Neisse (Nysa) to the Catholic faith. The work was completed by his successor, Charles Ferdinand, Prince of Poland (1625–55), who spent most of his time in his own country, but appointed excellent administrators for the diocese, such as the Coadjutor-Bishop Liesch von Hornau, and Archdeacon Gebauer. Imperial commissioners gave back to the Catholic Church those church buildings in the chief places of the principalities which had become the property of the sovereign through the extinction of vassal families. Until 1632 ''de facto'' rule was held in Warsaw by King Sigismund III and not by the bishop or archbishop.

According to the terms of the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two Peace treaty, peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy R ...

, the remaining churches, 693 in number, of such territories were secularized in the years 1653, 1654, and 1668. This led to a complete reorganization of the diocese. The person who effected it was Sebastian of Rostock, a man of humble birth who was vicar-general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop or archbishop of a diocese or an archdiocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vicar ...

and administrator of the diocese under the bishops Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1656–62) and Archduke Charles Joseph (1663–64), neither of whom lived in the territory of Breslau. After Sebastian of Rostock became bishop (1664–71) he carried on the work of reorganization with still greater success than before.

Frederick of Hesse-Darmstadt, Cardinal and

Frederick of Hesse-Darmstadt, Cardinal and Grand Prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be lowe ...

of the Order of St. John, was the next Bishop of Breslau (1671–82). The new bishop was of Protestant origin but had become a Catholic at Rome. Under his administration the rehabilitation of the diocese went on. He beautified the cathedral and elaborated its services. For the red cap and violet almutium of the canons he substituted the red mozzetta. He was buried in a beautiful chapel which he had added to the cathedral in honour of his ancestress, St. Elizabeth of Thuringia.

After his death the chapter presented Carl von Liechtenstein, Bishop of Olomouc, for confirmation. Their choice was opposed by the emperor, whose candidate was the Count Palatine

A count palatine (Latin ''comes palatinus''), also count of the palace or palsgrave (from German ''Pfalzgraf''), was originally an official attached to a royal or imperial palace or household and later a nobleman of a rank above that of an or ...

Wolfgang of the ruling family of Pfalz-Neuburg. Count Wolfgang died, and his brother Francis Louis (1683–1732) was made bishop. The new ruler of the diocese was at the same time Bishop of Worms, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order

The grand master of the Teutonic Order (; ) is the supreme head of the Teutonic Order. It is equivalent to the Grand master (order), grand master of other Military order (religious society), military orders and the superior general in non-milit ...

, Provost of Ellwangen

Ellwangen an der Jagst, officially Ellwangen (Jagst), in common use simply Ellwangen () is a town in the district of Ostalbkreis in the east of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. It is situated about north of Aalen.

Ellwangen has 25,000 inha ...

and Elector of Trier

The elector of Trier was one of the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire and, in his capacity as archbishop, administered the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier, archdiocese of Trier. The territories of the Electorate of Trier, electorate and t ...

, and later was made Elector of Mainz

The Elector of Mainz was one of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. As both the Archbishop of Mainz and the ruling prince of the Electorate of Mainz, the Elector of Mainz held a powerful position during the Middle Ages. The Archb ...

. He separated the ecclesiastical administration and that of the civil tribunals, and obtained the definition, in the Pragmatic Sanction of 1699, of the extent of the jurisdiction of the vicariate-general and the consistory. In 1675, upon the death of the last reigning Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of King Casimir III the Great.

Branches of ...

duke, the Silesian Duchy of Legnica-Brzeg-Wołów lapsed to the emperor, and a new secularization of the churches begun. But when King Charles XII of Sweden

Charles XII, sometimes Carl XII () or Carolus Rex (17 June 1682 – 30 November 1718 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.), was King of Sweden from 1697 to 1718. He belonged to the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, a branch line of the House of ...

secured for the Protestants the right to their former possessions in these territories, by the Treaty of Altranstädt, in 1707, the secularization came to an end, and the churches had to be returned. The Habsburg Emperor Joseph I endeavoured to repair the loss of these buildings to the Catholic faith by founding the so-called Josephine vicarships.

Within Prussia and the German Empire (main part) and the Bohemian Lands of Austria and Austria-Hungary (lesser part)

The next prince-bishop, Philip, Count von Sinzendorf, Cardinal and

The next prince-bishop, Philip, Count von Sinzendorf, Cardinal and Bishop of Győr

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

(1732–1747), owed his elevation to the favour of the emperor. During his episcopate, the greater part of the diocese was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

during the Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars () were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg Austria (under Empress Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

. King Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself '' King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prus ...

desired to erect a "Catholic Vicariate" at Berlin, to be the highest spiritual authority for the Catholics of Prussia. This would have been in reality a separation from Rome, and the project failed through the opposition of the Holy See. Bishop Sinzendorf had neither the acuteness to perceive the inimical intent of the king's scheme, nor sufficient decision of character to withstand it. The king desired to secure a successor to Sinzendorf who would be under royal influence. In utter disregard of the principles of the Church, and heedless of the protests of the cathedral chapter, he presented Count Philipp Gotthard von Schaffgotsch as coadjutor-bishop.

After the death of Cardinal Sinzendorf the king succeeded in the placement of Schaffgotsch as Bishop of Breslau (1748–95). Although the method of his elevation caused the new bishop to be regarded with suspicion by many strict Catholics, he was zealous in the fulfilment of his duties. During the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

he fell into discredit with Frederick on account of his firm maintenance of the rights of the Church, and the return of peace did not fully restore him to favour. In 1766 he fled to the Austrian part of his diocese in order to avoid confinement in Oppeln (Opole

Opole (; ; ; ) is a city located in southern Poland on the Oder River and the historical capital of Upper Silesia. With a population of approximately 127,387 as of the 2021 census, it is the capital of Opole Voivodeship (province) and the seat of ...

), which the king had decreed against him. After this Frederick made it impossible for him to rule the Prussian part of his diocese, and until the death of the bishop this territory was ruled by vicars Apostolic

An apostolic vicariate is a territorial jurisdiction of the Catholic Church under a titular bishop centered in missionary regions and countries where dioceses or parishes have not yet been established. The status of apostolic vicariate is often ...

.

The former coadjutor of von Schaffgotsch, Joseph Christian, Prince von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Bartenstein (1795–1817), succeeded him as bishop. During his episcopate the temporal power of the Bishops of Breslau came to an end through the secularization, in 1810, of the church estates in Prussian Silesia – only the estates in Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, was an autonomous region of the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Habsburg monarchy (from 1804 the Austrian Empire, and from 1867 the Cisleithanian portion of Austria-Hungary). It is la ...

remained to the see. The cathedral foundation, eight collegiate foundations, and over eighty monasteries were suppressed, and their property confiscated. Only those monastic institutions which were occupied with teaching or nursing were allowed to exist.

Bishop Joseph Christian was succeeded by his coadjutor, Emmanuel von Schimonsky. The affairs of the Catholic Church in Prussia had been brought into order by the Bull "De salute animarum", issued in 1821. Under its provisions the cathedral chapter elected Schimonsky, who had been administrator of the diocese, as Prince-Bishop of Breslau (1824–1832).

The bull disentangled Breslau diocese from Gniezno ecclesiastical province and made Breslau an exempt bishopric. The bull also reconfined the Breslau diocesan area which from then on remained unchanged until 1922. Breslau diocese then included the bulk of the Catholic parishes in the Prussian Province of Silesia

The Province of Silesia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1919. The Silesia region was part of the Prussian realm since 1742 and established as an official province in 1815, then became part of the German Empire in 1871. In 1919, as ...

with the exception of Catholic parishes in the districts of Ratibor (Racibórz

Racibórz (, , , ) is a city in Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland. It is the administrative seat of Racibórz County.

With Opole, Racibórz is one of the historic capitals of Upper Silesia, being the residence of the Duchy of Racibórz, Du ...

) and Leobschütz (Głubczyce

Głubczyce ( or sparsely ''Glubčice'', or ''Gubczycy'', ) is a town in Opole Voivodeship in south-western Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the administrative seat of Głubczyce County and Gmina Głubczyce.

Geography

Głu ...

), which until 1972 belonged to the Archdiocese of Olomouc, and Catholic parishes in the Prusso-Silesian County of Glatz (Kłodzko), which were subject to the Diocese of Hradec Králové within the Archdiocese of Prague until 1972. The Breslau Diocese included the Catholic parishes in the Duchy of Teschen

The Duchy of Teschen (), also Duchy of Cieszyn () or Duchy of Těšín (), was one of the Duchies of Silesia centered on Cieszyn () in Upper Silesia. It was split off the Silesian Duchy of Opole and Racibórz in 1281 during the feudal divisio ...

and the Austrian part of the Principality of Neisse. The bull also assigned the Prussian-annexed parts of the Apostolic Prefecture of Meissen in Lower Lusatia

Lower Lusatia (; ; ; ; ) is a historical region in Central Europe, stretching from the southeast of the Germany, German state of Brandenburg to the southwest of Lubusz Voivodeship in Poland. Like adjacent Upper Lusatia in the south, Lower Lusa ...

(politically part of Prussian Brandenburg

Brandenburg, officially the State of Brandenburg, is a States of Germany, state in northeastern Germany. Brandenburg borders Poland and the states of Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony. It is the List of Ger ...

since 1815) and eastern Upper Lusatia

Upper Lusatia (, ; , ; ; or ''Milsko''; ) is a historical region in Germany and Poland. Along with Lower Lusatia to the north, it makes up the region of Lusatia, named after the Polabian Slavs, Slavic ''Lusici'' tribe. Both parts of Lusatia a ...

(to Silesia province as of 1815) to Breslau diocese.

With the exception of the districts of Bütow (Bytów

Bytów (; ; ) is a town in the Gdańsk Pomerania region of northern Poland with 16,730 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is the capital of Bytów County in the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

In the early Middle Ages a fortified stronghold stood nea ...

) and Lauenburg (Pommern) (Lębork

Lębork (; ; ) is a town on the Łeba River, Łeba and Okalica rivers in the Gdańsk Pomerania region in northern Poland. It is the capital of Lębork County in Pomeranian Voivodeship. Its population is 37,000.

History Middle Ages

The region fo ...

), until 1922 both part of the Diocese of Culm/Chełmno, the rest of Brandenburg and Pomerania province were, since 1821, supervised by the Prince-Episcopal Delegation for Brandenburg and Pomerania.

Schimonsky retained for himself and his successors the title of prince-bishop, although the episcopal rule in the Principality of Neisse had ended by its secularization. However, the rank of prince-bishop later included the ex officio member

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term ''ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by ri ...

ship in the Prussian House of Lords

The Prussian House of Lords () in Berlin was the upper house of the Landtag of Prussia (), the parliament of Prussia from 1850 to 1918. Together with the lower house, the House of Representatives (), it formed the Prussian bicameral legislature ...

(since 1854) and in the Austrian House of Lords (since 1861).

Schimonsky combatted the rationalistic tendencies which were rife among his clergy in regard to celibacy and the use of Latin in the church services and ceremonies. During the episcopate of his predecessor the government had promulgated a law which was a source of much trouble to Schimonsky and his immediate successors; this was that in those places where Catholics were few in number, the parish should be declared extinct and the church buildings given to the newly founded Evangelical Church in Prussia. In spite of the protests of the episcopal authorities, over one hundred church buildings were lost in this way. King Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, when the empire was dissolved ...

put an end to this injustice, and sought to make good the injuries inflicted.

For several years after Schimonsky's death the see remained vacant. It was eventually filled by the election, through government influence, of Count Leopold von Sedlnitzky (1836–40). Prince-Bishop von Sedlnitzky was neither clear nor firm in his maintenance of the doctrines of the Church; on the question of mixed marriages, which had become one of great importance, he took an undecided position. At last, upon the demand of Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI (; ; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in June 1846. He had adopted the name Mauro upon enteri ...

, he resigned his see in 1840. He went afterwards to Berlin, where he was made a privy-councillor, and where he became a Protestant in 1862. In 1871 he died in Berlin and was buried in the Protestant cemetery in Rankau (today's Ręków, a part of Sobótka

Sobótka (pronounced , ) is a town in Wrocław County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. It is the seat of the administrative district (gmina) called Gmina Sobótka. It lies approximately southwest of Wrocław on the northern ...

).

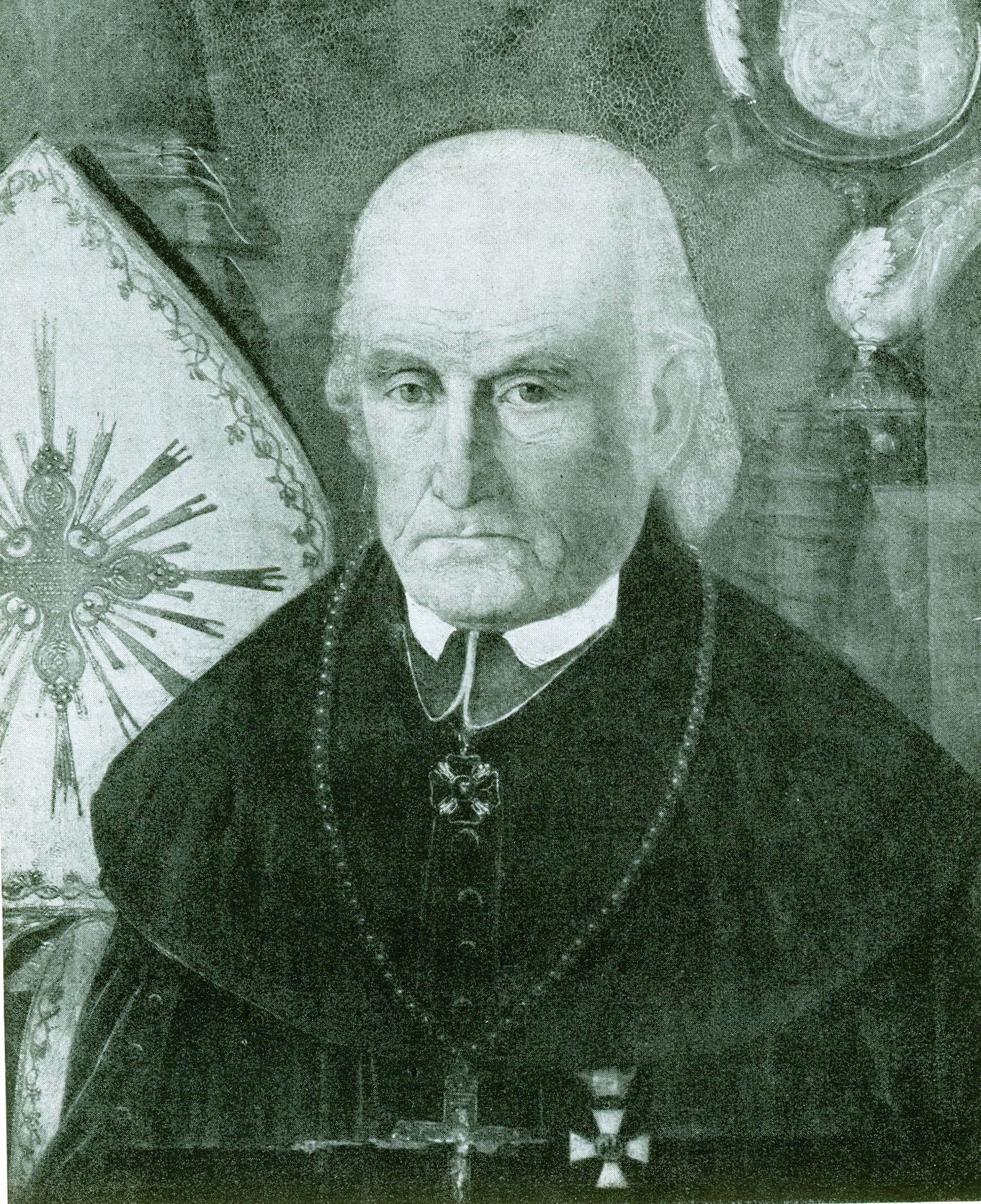

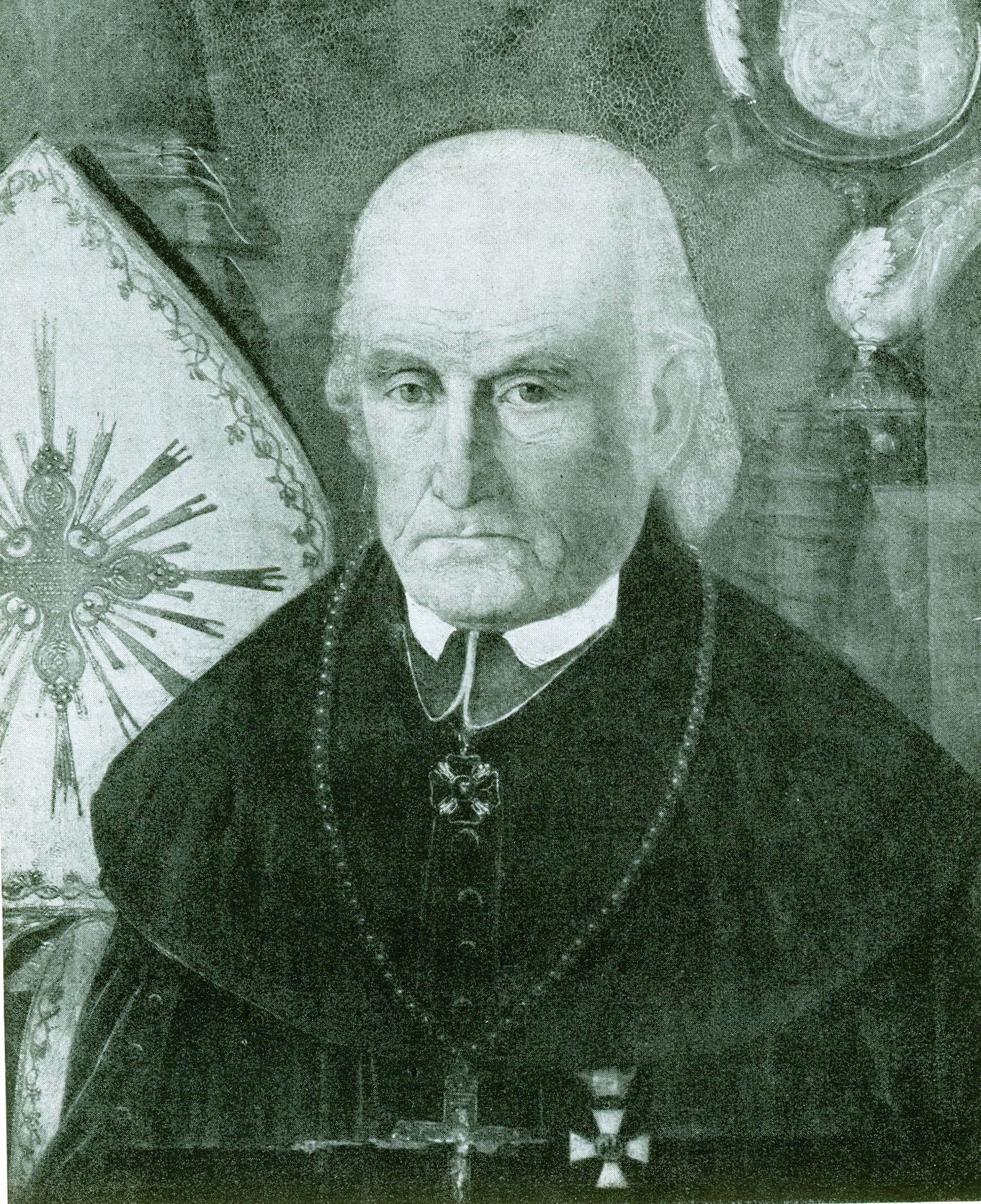

The dean of the cathedral, Dr. Ritter, administered the diocese for several years until the election of Joseph Knauer (1843–44), earlier Grand Dean of the Silesian County of Glatz within the Diocese of Hradec Králové. The new prince-bishop, who was 79 years old, lived only a year after his appointment.

His successor was Melchior, Freiherr von Diepenbrock (1845–53). This episcopate was the beginning of a new religious and ecclesiastical life in the diocese. During the revolutionary period the prince-bishop not only maintained order in his see, which was in a state of ferment, but was also a supporter of the government. He received unusual honours from the king and was made a cardinal by the Pope. He died 20 January 1853, at the Johannisberg (

The dean of the cathedral, Dr. Ritter, administered the diocese for several years until the election of Joseph Knauer (1843–44), earlier Grand Dean of the Silesian County of Glatz within the Diocese of Hradec Králové. The new prince-bishop, who was 79 years old, lived only a year after his appointment.

His successor was Melchior, Freiherr von Diepenbrock (1845–53). This episcopate was the beginning of a new religious and ecclesiastical life in the diocese. During the revolutionary period the prince-bishop not only maintained order in his see, which was in a state of ferment, but was also a supporter of the government. He received unusual honours from the king and was made a cardinal by the Pope. He died 20 January 1853, at the Johannisberg (Jánský Vrch

Jánský Vrch () is a castle located in the Jeseník District in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. The castle stands on a hill above the town of Javorník in the north-western edge of Czech Silesia, in area what was a part of the Duchy ...

) castle and was buried in the Breslau cathedral.

His successor, Heinrich Förster (1853–81), carried on his work and completed it. Prince-Bishop Förster gave generous aid to the founding of churches, monastic institutions, and schools. The strife that arose between the Church and the State brought his labours in the Prussian part of his diocese to an end. He was deposed by the State and was obliged to leave Breslau and retire to the Austrian Silesian castle of Johannisberg where he died, 20 October 1881; he was buried in the cathedral at Breslau.

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

appointed as his successor in the disordered diocese Robert Herzog (1882–86), who had been ''Prince-Episcopal Delegate for Brandenburg and Pomerania'' and provost of St. Hedwig's in Berlin. Prince-Bishop Herzog made every endeavour to bring order out of the confusion into which the quarrel with the State during the immediately preceding years had thrown the affairs of the diocese. His episcopate was but of short duration; he died after a long illness, 26 December 1886.

The Holy See appointed as his successor a man who had done much to allay the strife between Church and State, the Bishop of Fulda, Georg Kopp. He was transferred from Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a city in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the city hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

Histor ...

to Breslau and installed 20 October 1887; later created a cardinal (1893).

According to the census of 1 December 1905, the German part of Breslau diocesan area, including the prince-episcopal delegation, comprised 3,342,221 Catholics; 8,737,746 Protestants; and 204,749 Jews. It was the richest German diocese in revenues and offertories. There were actively employed in the diocese 1,632 secular and 121 regular, priests. The cathedral chapter included the two offices of provost and dean, and had 10 regular, and 6 honorary, canons.

The prince-bishopric was divided into 11 commissariates and 99 archipresbyterates, in which there were 992 cures of various kinds (parishes, curacies, and stations), with 935 parish churches and 633 dependent and mother-churches. Besides the theological faculty of the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Breslau, the diocese possessed, as episcopal institutions for the training of the clergy, 5 preparatory seminaries for boys, 1 home (recently much enlarged) for theological students attending the university, and 1 seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

for priests in Breslau. The statistics of the houses of the religious orders in the dioceses were as follows:

*Benedictines

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly Christian mysticism, contemplative Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), order of the Catholic Church for men and f ...

, 1 house

*Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

, 1

*Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

, 8

*Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, 3

*Piarists

The Piarists (), officially named the Order of Poor Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of the Pious Schools (), abbreviated SchP, is a religious order of clerics regular of the Catholic Church founded in 1617 by Spanish priest Joseph Calasanz ...

, 1

* Brothers of Mercy, 8

* Order of St. Camillus of Lellis, 1

*Redemptorists

The Redemptorists, officially named the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (), abbreviated CSsR, is a Catholic clerical religious congregation of pontifical right for men (priests and brothers). It was founded by Alphonsus Liguori at Scala ...

, 1

* Congregation of the Society of the Divine Word, 1

* Alexian Brothers, 1

* Poor Brothers of St. Francis, 2

* Sisters of St. Elizabeth, 6

* Magdalen Sisters, 1

*Ursulines

The Ursulines, also known as the Order of Saint Ursula (post-nominals: OSU), is an enclosed religious order of women that in 1572 branched off from the Angelines, also known as the Company of Saint Ursula. The Ursulines trace their origins to th ...

, 6

* Sisters of the Good Shepherd, 4

* Sisters of St. Charles Borromeo, (a) from the mother-house at Trebnitz, 181, (b) from the mother-house at Trier, 5

*Servants of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

A domestic worker is a person who works within a residence and performs a variety of household services for an individual, from providing cleaning and household maintenance, or cooking, laundry and ironing, or childcare, care for children and ...

, 2

*Sisters of Poor Handmaids of Christ

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a family, familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly t ...

, 3

* Sister-Servants of Mary, 27

* German Dominican Sisters of St. Catharine of Siena, 11

* Sisters of St. Francis, 9

* Grey Sisters of St. Elizabeth, 169

* Sisters of St. Hedwig, 9

* Sisters of Mary, 27

* Poor School-Sisters of Notre Dame, 15

* Vincentian Sisters, 7

*Sisters of the Holy Cross

The Sisters of the Holy Cross are one of three Roman Catholic Church, Catholic Religious congregation, congregations of nuns, religious sisters which trace their origins to the foundation of the Congregation of Holy Cross by Basil Moreau in Le Ma ...

, 1

* Sisters of St. Joseph, 1

In the above-mentioned monastic houses for men there were 512 religious; in those for women, 5,208 religious.

Within the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany, Czechoslovakia and the Second Polish Republic

AfterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Poles and Czechs regained independence, and the Duchy of Teschen

The Duchy of Teschen (), also Duchy of Cieszyn () or Duchy of Těšín (), was one of the Duchies of Silesia centered on Cieszyn () in Upper Silesia. It was split off the Silesian Duchy of Opole and Racibórz in 1281 during the feudal divisio ...

, until 1918 politically an Austro-Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

fief and ecclesiastically a part of the Breslau diocese, was politically divided into a Czechoslovak western and a Polish eastern part ( Cieszyn/Těšín Silesia), even dividing its capital into Czech Těšín and Polish Cieszyn

Cieszyn ( , ; ; ) is a border town in southern Poland on the east bank of the Olza River, and the administrative seat of Cieszyn County, Silesian Voivodeship. The town has 33,500 inhabitants ( and lies opposite Český Těšín in the Czech Repu ...