Rollo Howard Beck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rollo Howard Beck (26 August 1870 – 22 November 1950) was an American

The Pacific Voyages of Rollo Beck

Web link invalid March 18, 2014; still invalid September 9, 2016. {{DEFAULTSORT:Beck, Rollo American explorers American ornithologists 1870 births 1950 deaths American explorers of the Pacific People associated with the California Academy of Sciences People from Los Gatos, California Scientists from the San Francisco Bay Area 19th-century American zoologists 20th-century American zoologists

ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

, bird collector for museums, and explorer. Beck's petrel

Beck's petrel (''Pseudobulweria becki'') is a small species of petrel. Its specific epithet commemorates American ornithologist Rollo Beck. It is believed to nest on small islands with tall mountains around Melanesia. Described in 1928, and long ...

and three taxa of reptiles are named after him, including a subspecies of Galápagos tortoise, ''Chelonoidis nigra becki'' from Volcán Wolf

Wolf Volcano ( es, Volcán Wolf, italic=no), also known as Mount Whiton, is the highest peak in the Galápagos Islands. It is situated on Isabela Island and reaches . It is a shield volcano with a characteristic upturned soup bowl shape.

The vo ...

. A recent paper by Fellers examines all the known taxa named for Beck. Beck was recognized for his extraordinary ability as a field worker by Robert Cushman Murphy as being "in a class by himself," and by University of California at Berkeley professor of zoology Frank Pitelka

Frank Alois Pitelka (27 March 1916 – 10 October 2003) was an American ornithologist. He was the 2001 recipient of the Cooper Ornithological Society’s Loye and Alden Miller Research Award, which is given in recognition of lifetime achievement ...

as "''the'' field worker" of his generation.

Early years

Rollo Howard Beck was born inLos Gatos, California

Los Gatos (, ; ) is an incorporated town in Santa Clara County, California, United States. The population is 33,529 according to the 2020 census. It is located in the San Francisco Bay Area just southwest of San Jose in the foothills of the ...

, and grew up in Berryessa working on apricot and prune orchards. He completed only an 8th grade education, but took an early interest in natural history, trapping gophers

Pocket gophers, commonly referred to simply as gophers, are burrowing rodents of the family Geomyidae. The roughly 41 speciesSearch results for "Geomyidae" on thASM Mammal Diversity Database are all endemic to North and Central America. They are ...

after school on neighborhood farms. One of his neighbors, Frank H. Holmes, was a good friend of the ornithologist Theodore Sherman Palmer. Palmer also introduced Beck to Charles Keeler

Charles Augustus Keeler (October 7, 1871 – July 31, 1937) was an American author, poet, ornithologist and advocate for the arts, particularly architecture.

Biography

Early life

Charles Keeler was born on October 7, 1871 in Milwaukee, Wisconsi ...

, who studied birdlife of the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

, and Beck learned about upland birds hunting quail with Holmes. Beck's interest and knowledge of birds grew, and he soon learned how to make ornithological specimens and mount birds for museum collections

A museum is distinguished by a collection of often unique objects that forms the core of its activities for exhibitions, education, research, etc. This differentiates it from an archive or library, where the contents may be more paper-based, repla ...

. He joined the American Ornithologists' Union

The American Ornithological Society (AOS) is an ornithological organization based in the United States. The society was formed in October 2016 by the merger of the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) and the Cooper Ornithological Society. Its m ...

in 1894, and was among the first members of the newly formed Cooper Ornithological Society which formed in San Jose, California

San Jose, officially San José (; ; ), is a major city in the U.S. state of California that is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley and largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 popul ...

. He participated in early ornithological expeditions to the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

Mountains, Yosemite

Yosemite National Park ( ) is an American national park in California, surrounded on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service and covers an ar ...

, and Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe (; was, Dáʔaw, meaning "the lake") is a Fresh water, freshwater lake in the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada of the United States. Lying at , it straddles the state line between California and Nevada, west of Carson City, Nevad ...

with Holmes and Wilfred Hudson Osgood, and collected and helped describe the first eggs and nests of the western evening grosbeak

The evening grosbeak (''Hesperiphona vespertina'') is a passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae found in North America.

Taxonomy

The IOC checklist and the ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'' place the evening grosbeak and the closel ...

and hermit warbler

The hermit warbler (''Setophaga occidentalis'') is a small perching bird. It is a species of New World warbler or wood-warbler. They are a migratory bird, the breeding range spanning the majority of the west coast of the United States. Their wint ...

.

Expeditions

Channel Islands of California

In the spring of 1897, Beck headed south toSanta Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Coas ...

, where he learned to sail a moderate-sized schooner under captain Sam Burtis. He visited the Channel Islands of California, including Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa is the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish name for Saint Rose.

Santa Rosa may also refer to:

Places Argentina

*Santa Rosa, Mendoza, a city

* Santa Rosa, Tinogasta, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, Valle Viejo, Catamarca

*Santa Rosa, La Pampa

* Sa ...

, and San Miguel islands collecting and documenting birds as well as nests and eggs. Beck was the first to collect and document the differences of the island scrub-jay

The island scrub jay (''Aphelocoma insularis''), also known as the island jay or Santa Cruz jay, is a bird in the genus, ''Aphelocoma'', which is endemic to Santa Cruz Island off the coast of Southern California. Of the over 500 breeding bird spe ...

s that live on the Channel Islands, now recognized as distinct from mainland forms.

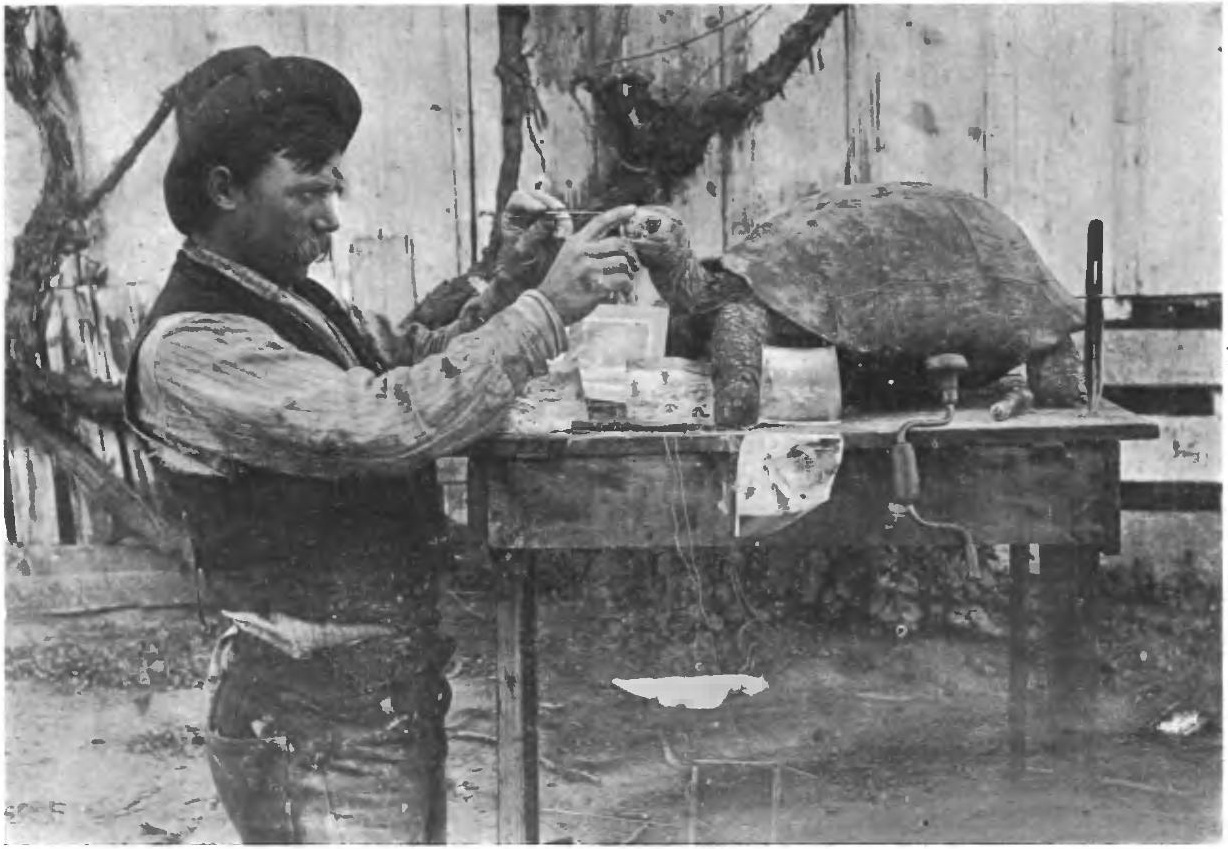

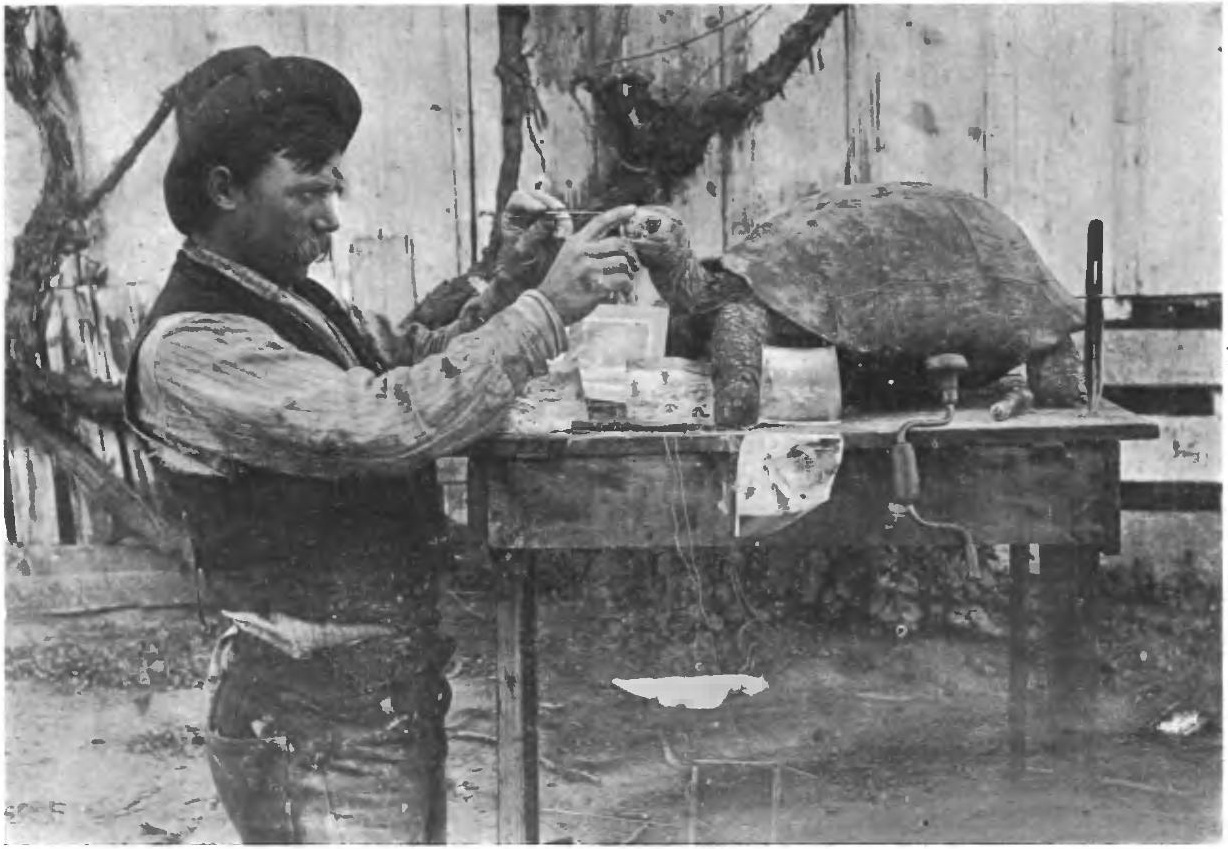

Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

Later in 1897, while on his way back to theSierra Nevada Mountains

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley (California), Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Cars ...

, Beck was invited to join an ornithological expedition to the Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

off the coast of Ecuador, organized by Frank Blake Webster and funded by Lionel Walter Rothschild, of Tring, England, later, and only after his father's death in 1915, Lord Rothschild. The expedition was launched to study and collect giant tortoises and the land birds of the Galápagos, and here Beck also polished his sailing skills and became better acquainted with seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s and the unique fauna of the Galápagos. Beck returned again to the Galápagos to collect more specimens around 1901, and he personally delivered these specimens to Walter Rothschild in Tring. While in Tring, he planned future potential collecting trips to Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

for Rothschild, and he returned to California by way of Washington, DC, in order to apply for the necessary permits.

Cocos and Galápagos

Back in San Francisco, Beck met with Leverett Mills Loomis, Director of theCalifornia Academy of Sciences

The California Academy of Sciences is a research institute and natural history museum in San Francisco, California, that is among the largest museums of natural history in the world, housing over 46 million specimens. The Academy began in 1853 ...

. Loomis was interested in seabirds, especially the Tubinares, now the Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are of ...

, and hired Beck to collect in Monterey Bay, the Channel Islands of California, and the Revillagigedo Islands of Mexico, while he waited for his Colombia permits. In 1905–1906, Beck was hired by the California Academy of Sciences to organize and lead a large seagoing expedition to Cocos Island

Cocos Island ( es, Isla del Coco) is an island in the Pacific Ocean administered by Costa Rica, approximately southwest of the Costa Rican mainland. It constitutes the 11th of the 13 districts of Puntarenas Canton of the Province of Puntarenas ...

and the Galápagos Islands aboard the Schooner “Academy.” Loomis organized scientific specialists in botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, herpetology

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

, entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

, and malacology

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology that deals with the study of the Mollusca (mollusks or molluscs), the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

, paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, as well as ornithology. Besides Beck, the expedition's scientists were: Alban Stewart, botanist; W. H. Ochsner, geologist/paleontologist/malacologist; F. X. Williams, entomologist/malacologist; E. W. Gifford and J. S. Hunter, ornithologists; J. R. Slevin and E. S. King, herpetologists. Together they assembled the largest scientific collection of specimens from the archipelago ever, leading to our great understanding of the biota of the islands.

The great April 18, 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

and three days of subsequent fire struck while Beck and the expedition were still in the Galápagos Islands. They would not return to San Francisco until Thanksgiving Day, November 29, 1906. Their extensive collections of some 78,000 specimens allowed the Academy as an institution to rise, literally and figuratively, from the ashes of "the great conflagration" that devastated San Francisco. The schooner “Academy” acted as the meeting place and storage place for the California Academy of Sciences for several months after their return. Some historians believe that had Beck and the expedition not been out to sea and collecting, the Academy would have suffered a lethal blow.

Beck married his wife and lifelong companion, Ida Menzies of Berryessa, in 1907 in Honolulu, Hawaii. He went to work for Joseph Grinnell, the Director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, in the spring of 1908, and collected waterbird

A water bird, alternatively waterbird or aquatic bird, is a bird that lives on or around water. In some definitions, the term ''water bird'' is especially applied to birds in freshwater ecosystems, although others make no distinction from seabi ...

s for Grinnell's studies of California birds. Before long, Beck was offered even more money by Dr. Leonard C. Sanford, of New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, to collect birds in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

for the well-known ornithologist Arthur Cleveland Bent

Arthur Cleveland Bent (November 25, 1866 – December 30, 1954) was an American ornithologist. He is notable for his encyclopedic 21-volume work, ''Life Histories of North American Birds'', published 1919-1968 and completed posthumously.

Bent wa ...

, who was collecting for his studies of “The Life Histories of North American Birds.” He did much of the field work with the young Alexander Wetmore, who had recently graduated from college.

Brewster-Sanford Expedition to South America

In 1912, Dr. Leonard Cutler Sanford proposed a larger two-year expedition (that ended up taking five years) to South America for Rollo and Ida, and financed by Mr. F. F. Brewster. They traveled up into lakes and highlands of theAndes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

, along the coast, and out at sea to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

and Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

, sailed around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

in a 12-ton cutter, and up into the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. This work and these collections proved invaluable to Robert Cushman Murphy, who later published “The Oceanic Birds of South America” based in part on the Brewster-Sanford Expedition collection of Rollo Beck.

Whitney South Seas Expedition

In 1920 Beck was contacted by Dr. Sanford who proposed an extended South Pacific expedition. The fieldwork was funded byHarry Payne Whitney

Harry Payne Whitney (April 29, 1872 – October 26, 1930) was an American businessman, thoroughbred horse breeder, and member of the prominent Whitney family.

Early years

Whitney was born in New York City on April 29, 1872, as the eldest son ...

of New York, and the specimens were bound for the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

. This became the longest and greatest of all Beck's expeditions and, as with the "Academy" expedition of 1905–06, he was joined by many other accomplished biologists and field collectors with complementary skills, including E. H. Quayle, J. G. Correia, Dr F. P. Drowne, Hannibal Hamlin, Guy Richards, Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

, E. H. Bryan Jr., and others. Beck left the expedition in 1929, after sailing through the Pacific, from Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

and visiting hundreds of islands between. Rollo and Ida Beck returned to the California in 1929 with over 40,000 bird skins and a large anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

collection. This expedition remains to this day the most comprehensive survey and study of birds in the south-west Pacific islands, and has been written up in dozens of important scientific monographs of birds. The specimens residing at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City form the most comprehensive collection of Pacific birds anywhere.

Rollo and Ida Beck retired to the northern California town of Planada, near Merced, where they continued to study natural history and provide specimens of great scientific value. Most of these later specimens are housed at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, and at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

. There is also a substantial collection at San Jose State University

San José State University (San Jose State or SJSU) is a public university in San Jose, California. Established in 1857, SJSU is the oldest public university on the West Coast and the founding campus of the California State University (CSU) sys ...

. There is a smaller collection of mounted specimens on exhibit at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History

The Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History is a museum of natural history located near the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Pacific Grove, California, United States. The museum is a living field guide of the California Central Coast showcasing local na ...

, in the town of Pacific Grove, California

Pacific Grove is a coastal city in Monterey County, California, in the United States. The population at the 2020 census was 15,090. Pacific Grove is located between Point Pinos and Monterey.

Pacific Grove has numerous Victorian-era houses, so ...

, as well as a permanent exhibit devoted to the life and work of Rollo Beck.

Contributions to science

The work of Beck and other early ornithologists was undertaken primarily to document biodiversity before it was lost forever without being recorded, and to understand the evolution and ecology of organisms from the regions visited during the expeditions. The work of Beck and others brought an awareness of and a catalog of regional biodiversity that is essential to have in order to do modern conservation. Much of what we know about western U.S. birds and Pacific ornithology – from Bent's "Life Histories of North American Birds" to Murphy's "Oceanic Birds of South America" - rests on the fieldwork of Rollo Beck and other early ornithologists. Some believe that our understanding of global biodiversity and the practice of modern conservation biology, much of which seems to be anti-collecting, owes much to these early collectors who worked so diligently to document and preserve voucher specimens in museums.Controversy

Human history is replete with examples of island species that were being persecuted by farmers, ranchers, hunters, and sailors; were being harvested unsustainably; and were being decimated by introduced species. By comparison, scientific collectors were relatively few in number and seldom took large numbers of specimens of any one species, but competition between museums and private collectors to acquire the rarest of the rare put disproportionate collecting pressure on species whose populations were already teetering on the brink for other reasons. Beck and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were responding to published statements that "time was running out" and that species should be collected and documented in museum collections "before it is too late." In the absence of a conservation framework and infrastructure, Beck and others engaged in what can be called "salvage collecting," which hastened the extinctions and which does not correspond to modern conservation thinking. Rollo Beck has been blamed for having collected a sample ofGuadalupe caracara

The Guadalupe caracara (''Caracara lutosa'') or mourning caracara is an extinct bird of prey belonging to the falcon family (Falconidae). It was, together with the closely related crested caracara (''Caracara plancus''), formerly placed in the ...

s in 1900 which were being exterminated by goat herders who viewed the bird as a predator. At the time he assumed the birds were common on Guadalupe Island, but in retrospect he wrote that those he collected might have been the last. Beck also collected, as museum specimens, three of the last four individuals of the subspecies of Galápagos tortoise

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a species of very large tortoise in the genus ''Chelonoidis'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). It comprises 15 subspecies (13 ...

''Geochelone nigra abingdonii'', the Pinta Island tortoise. The last individual of that island's tortoise population became known as Lonesome George

Lonesome George ( es, Solitario George or , 1910 – June 24, 2012) was a male Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger abingdonii'') and the last known individual of the subspecies. In his last years, he was known as the rarest creat ...

when it was found on Pinta Island in November 1971.

Reptiles named in honor of Beck

Rollo Beck is commemorated in the scientific names of three taxa of reptiles.Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). ''The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. . ("Beck", p. 21). *''Chelonoidis nigra becki

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the Galápagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of t ...

'', a tortoise

*'' Sceloporus becki'', a lizard

*''Sphaerodactylus becki

Beck's least gecko (''Sphaerodactylus becki'') is a species of lizard in the family Sphaerodactylidae. The species is endemic to Navassa Island.

Etymology

The specific name, ''becki'', is in honor of American ornithologist Rollo Howard Beck.Be ...

'', a lizard

References

External links

*The Pacific Voyages of Rollo Beck

Web link invalid March 18, 2014; still invalid September 9, 2016. {{DEFAULTSORT:Beck, Rollo American explorers American ornithologists 1870 births 1950 deaths American explorers of the Pacific People associated with the California Academy of Sciences People from Los Gatos, California Scientists from the San Francisco Bay Area 19th-century American zoologists 20th-century American zoologists