Robin Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robin Morgan (born January 29, 1941) is an American poet, writer, activist, journalist, lecturer and former child actor. Since the early 1960s, she has been a key

Due to circumstances at her birth, her mother claimed that Robin Morgan was born a year later than she actually was (see birth and parents), and throughout her career as a child actor, she was thought to be a year younger than she actually was, both by herself and others.

Already as a toddler, her mother, Faith, and mother's sister Sally, started Robin Morgan as a child model. At the age of five, believed to be four, she got her own program, titled ''Little Robin Morgan'', on the New York radio station WOR. She was also a regular on the original network radio version of ''

Due to circumstances at her birth, her mother claimed that Robin Morgan was born a year later than she actually was (see birth and parents), and throughout her career as a child actor, she was thought to be a year younger than she actually was, both by herself and others.

Already as a toddler, her mother, Faith, and mother's sister Sally, started Robin Morgan as a child model. At the age of five, believed to be four, she got her own program, titled ''Little Robin Morgan'', on the New York radio station WOR. She was also a regular on the original network radio version of ''

In 1962, Morgan married poet Kenneth Pitchford. She gave birth to their son, Blake Morgan, in 1969. The couple divorced in 1983. At that time, she was working as an editor at

In 1962, Morgan married poet Kenneth Pitchford. She gave birth to their son, Blake Morgan, in 1969. The couple divorced in 1983. At that time, she was working as an editor at

In 1970, Morgan compiled, edited, and introduced the first

In 1970, Morgan compiled, edited, and introduced the first

radical feminist

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other ...

member of the American Women's Movement, and a leader in the international feminist movement. Her 1970 anthology ''Sisterhood Is Powerful

''Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement'' is a 1970 anthology of feminist writings edited by Robin Morgan, a feminist poet and founding member of New York Radical Women. It is one of the first widel ...

'' was cited by the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress) ...

as "One of the 100 Most Influential Books of the 20th Century." She has written more than 20 books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and was editor of ''Ms.

Ms. (American English) or Ms (British English; normally , but also , or when unstressed)''Oxford English Dictionary'' online, Ms, ''n.2''. Etymology: "An orthographic and phonetic blend of Mrs ''n.1'' and miss ''n.2'' Compare mizz ''n.'' The pr ...

'' magazine.

During the 1960s, she participated in the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

and anti-Vietnam War

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social mov ...

movements; in the late 1960s, she was a founding member of radical feminist organizations such as New York Radical Women and W.I.T.C.H.

''W.I.T.C.H.'' (stylised as ''W.i.t.c.h.'') is an Italian fantasy Disney comics series created by Elisabetta Gnone, Alessandro Barbucci, and Barbara Canepa. The series features a group of five teenage girls who become the guardians of the class ...

She founded or co-founded the Feminist Women's Health Network, the National Battered Women's Refuge Network, Media Women, the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers, the Feminist Writers' Guild, the Women's Foreign Policy Council, the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), located in Washington, D.C., is "the first museum in the world solely dedicated" to championing women through the arts. NMWA was incorporated in 1981 by Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. Since openi ...

, the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, GlobalSister.org, and Greenstone Women's Radio Network. She also co-founded the Women's Media Center

Women's Media Center (WMC) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit women's organization in the United States founded in 2005 by writers and activists Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem.

with activist Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

and actor/activist Jane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress, activist, and former fashion model. Recognized as a film icon, Fonda is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Jane Fonda, various accolades including two ...

. In 2018, she was listed as one of BBC's 100 Women.

Child actor

Due to circumstances at her birth, her mother claimed that Robin Morgan was born a year later than she actually was (see birth and parents), and throughout her career as a child actor, she was thought to be a year younger than she actually was, both by herself and others.

Already as a toddler, her mother, Faith, and mother's sister Sally, started Robin Morgan as a child model. At the age of five, believed to be four, she got her own program, titled ''Little Robin Morgan'', on the New York radio station WOR. She was also a regular on the original network radio version of ''

Due to circumstances at her birth, her mother claimed that Robin Morgan was born a year later than she actually was (see birth and parents), and throughout her career as a child actor, she was thought to be a year younger than she actually was, both by herself and others.

Already as a toddler, her mother, Faith, and mother's sister Sally, started Robin Morgan as a child model. At the age of five, believed to be four, she got her own program, titled ''Little Robin Morgan'', on the New York radio station WOR. She was also a regular on the original network radio version of ''Juvenile Jury

''Juvenile Jury'' was an American children's game show that originally ran on NBC from April 3, 1947, to August 1, 1954. It was hosted by Jack Barry and featured a panel of children aged ten or less giving advice to solve the problems of other ch ...

''. Her acting career took off when she was eight and started in the TV series ''Mama

Mama(s) or Mamma or Momma may refer to:

Roles

*Mother, a female parent

* Mama-san, in Japan and East Asia, a woman in a position of authority

*Mamas, a name for female associates of the Hells Angels

Places

* Mama, Russia, an urban-type settlemen ...

'', as Dagmar Hansen, the younger sister in the family depicted in the series. The show premiered on CBS in 1949, starring Peggy Wood, and was a great success. Morgan played Cecchina Cabrini in ''Citizen Saint

'' Citizen Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini'' is a 1947 film about a Catholic saint. It was directed by Harold Young. It was produced by Clyde Elliott Attractions. It is about Frances Xavier Cabrini, an Italian woman who becomes a nun and is eve ...

'' (1947).

During the Golden Age of Television

The first Golden Age of Television is an era of television in the United States marked by its large number of live productions. The period is generally recognized as beginning in 1947 with the first episode of the drama anthology '' Kraft Televi ...

, Morgan starred in such "TV spectaculars" as ''Kiss and Tell'' and ''Alice in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatur ...

'', and guest starred on such live dramas as '' Omnibus'', ''Suspense

Suspense is a state of mental uncertainty, anxiety, being Decision-making, undecided, or being Doubt, doubtful. In a Drama, dramatic work, suspense is the anticipation of the wikt:outcome, outcome of a plot (narrative), plot or of the solution t ...

'', ''Danger

Danger is a lack of safety and may refer to:

Places

* Danger Cave, an archaeological site in Utah

* Danger Island, Great Chagos Bank, Indian Ocean

* Danger Island, alternate name of Pukapuka Atoll in the Cook Islands, Pacific Ocean

* Danger Is ...

'', ''Hallmark Hall of Fame

''Hallmark Hall of Fame'', originally called ''Hallmark Television Playhouse'', is an anthology program on American television, sponsored by Hallmark Cards, a Kansas City-based greeting card company. The longest-running prime-time series in ...

'', '' Robert Montgomery Presents'', ''Tales of Tomorrow

''Tales of Tomorrow'' is an American anthology science fiction series that was performed and broadcast live on ABC from 1951 to 1953. The series covered such stories as ''Frankenstein'' starring Lon Chaney Jr., '' 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea'' ...

'', and '' Kraft Theatre''. She worked with directors such as Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. He was nominated five times for the Academy Award: four for Best Director for ''12 Angry Men'' (1957), '' Dog Day Afternoon'' (1975), ''Network'' (1976 ...

, John Frankenheimer

John Michael Frankenheimer (February 19, 1930 – July 6, 2002) was an American film and television director known for social dramas and action/suspense films. Among his credits were ''Birdman of Alcatraz'' (1962), '' The Manchurian Candidate'' ( ...

, Ralph Nelson

Ralph Nelson (August 12, 1916 – December 21, 1987) was an American film and television director, producer, writer, and actor. He was best known for directing '' Lilies of the Field'' (1963), '' Father Goose'' (1964), and '' Charly'' (1968 ...

; writers such as Paddy Chayefsky

Sidney Aaron "Paddy" Chayefsky (January 29, 1923 – August 1, 1981) was an American playwright, screenwriter and novelist. He is the only person to have won three solo Academy Awards for writing both adapted and original screenplays.

He was ...

and Rod Serling

Rodman Edward Serling (December 25, 1924 – June 28, 1975) was an American screenwriter, playwright, television producer, and narrator/on-screen host, best known for his live television dramas of the 1950s and his anthology television series ...

; and performed with actors such as Boris Karloff

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff (), was an English actor. His portrayal of Frankenstein's monster in the horror film ''Frankenstein'' (1931) (his 82nd film) established ...

, Rosalind Russell

Catherine Rosalind Russell (June 4, 1907November 28, 1976) was an American actress, comedienne, screenwriter, and singer,Obituary '' Variety'', December 1, 1976, p. 79. known for her role as fast-talking newspaper reporter Hildy Johnson in the H ...

, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson

Bill Robinson, nicknamed Bojangles (born Luther Robinson; May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949), was an American tap dancer, actor, and singer, the best known and the most highly paid African-American entertainer in the United States during the f ...

, and Cliff Robertson.

Having wanted to write rather than to act since she was four, Morgan fought her mother's efforts to keep her in show business, and left the cast of ''Mama'' at age 14.

Adult career

As she entered adulthood, Robin Morgan continued her education as a non-matriculating student atColumbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. She began working as a secretary at Curtis Brown Literary Agency, where she met and worked with such writers as poet W. H. Auden in the early 1960s. She had already begun publishing her own poetry (later collected in her first book of poems, ''Monster'', published in 1972). Throughout the next decades, along with political activism, writing fiction and nonfiction prose, and lecturing at colleges and universities on women's rights, Morgan continued to write and publish poetry.

In 1962, Morgan married poet Kenneth Pitchford. She gave birth to their son, Blake Morgan, in 1969. The couple divorced in 1983. At that time, she was working as an editor at

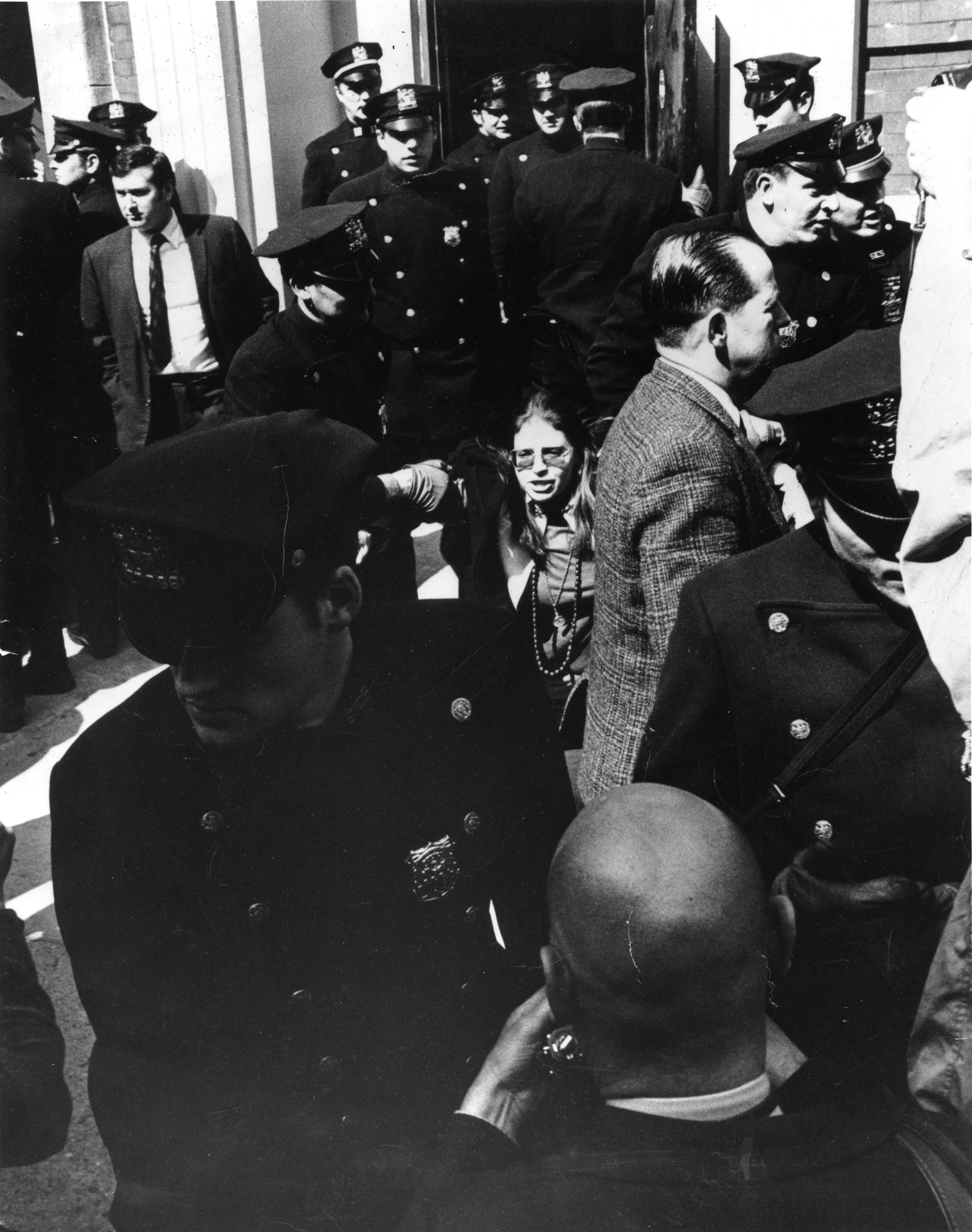

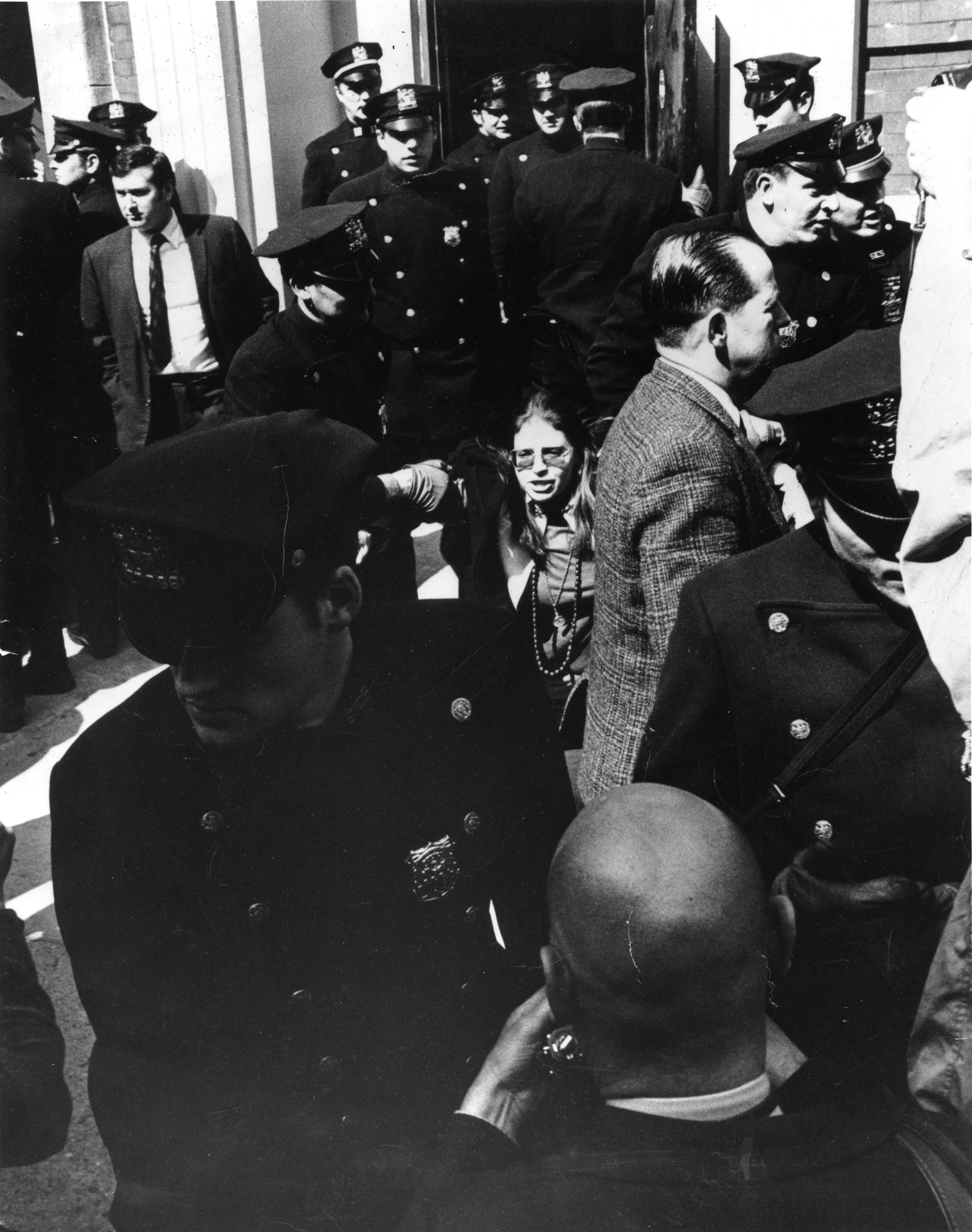

In 1962, Morgan married poet Kenneth Pitchford. She gave birth to their son, Blake Morgan, in 1969. The couple divorced in 1983. At that time, she was working as an editor at Grove Press

Grove Press is an American publishing imprint that was founded in 1947. Imprints include: Black Cat, Evergreen, Venus Library, and Zebra. Barney Rosset purchased the company in 1951 and turned it into an alternative book press in the United Sta ...

and was involved in an attempt to unionize

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

the publishing industry. When Grove summarily fired her and other union sympathizers, she led a seizure and occupation of their offices in the spring of 1970, protesting the union-busting

Union busting is a range of activities undertaken to disrupt or prevent the formation of trade unions or their attempts to grow their membership in a workplace.

Union busting tactics can refer to both legal and illegal activities, and can range ...

, as well as the dishonest accounting of royalties

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset o ...

to Betty Shabazz

Betty Shabazz (born Betty Dean Sanders; May 28, 1934/1936 – June 23, 1997), also known as Betty X, was an American educator and civil rights advocate. She was married to Malcolm X.

Shabazz grew up in Detroit, Michigan, where her foste ...

, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

's widow. Morgan and eight other women were arrested that day.

In the mid-1970s Morgan became a Contributing Editor to ''Ms.

Ms. (American English) or Ms (British English; normally , but also , or when unstressed)''Oxford English Dictionary'' online, Ms, ''n.2''. Etymology: "An orthographic and phonetic blend of Mrs ''n.1'' and miss ''n.2'' Compare mizz ''n.'' The pr ...

'' magazine, and continued her affiliation there as a part- or full-time editor in the following decades. She served as editor-in-chief

An editor-in-chief (EIC), also known as lead editor or chief editor, is a publication's editorial leader who has final responsibility for its operations and policies.

The highest-ranking editor of a publication may also be titled editor, managing ...

of the magazine from 1989 to 1994, turning it into a highly successful, ad-free, bimonthly, international publication, which won awards for both writing and design, and received considerable acclaim among journalists.

In 1979, when the Supersisters

''Supersisters'' was a set of 72 trading cards produced and distributed in the United States in 1979 by Supersisters, Inc. They featured famous women from politics, media and entertainment, culture, sports, and other areas of achievement. The c ...

trading card set was produced and distributed, featuring famous women from politics, media and entertainment, culture, sports, and other areas of achievement, one of the cards featured Morgan's name and picture. Today, the trading cards are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of t ...

and the University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (UI, U of I, UIowa, or simply Iowa) is a public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized into 12 co ...

library.

In 2005, Morgan co-founded the non-profit progressive women's media organization, The Women’s Media Center, with friends actor/activist Jane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress, activist, and former fashion model. Recognized as a film icon, Fonda is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Jane Fonda, various accolades including two ...

, and activist Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

. Seven years later, in 2012, she debuted a weekly radio show and podcast

A podcast is a program made available in digital format for download over the Internet. For example, an episodic series of digital audio or video files that a user can download to a personal device to listen to at a time of their choosin ...

, ''Women’s Media Center Live With Robin Morgan.'' The broadcast is syndicated in the US and, as a podcast, is published online at the WMCLive website, and distributed on iTunes

iTunes () is a software program that acts as a media player, media library, mobile device management utility, and the client app for the iTunes Store. Developed by Apple Inc., it is used to purchase, play, download, and organize digital mu ...

in 110 countries. It has been praised by ''The Huffington Post

''HuffPost'' (formerly ''The Huffington Post'' until 2017 and sometimes abbreviated ''HuffPo'') is an American progressive news website, with localized and international editions. The site offers news, satire, blogs, and original content, and ...

'' as "talk radio with a brain" and features commentary by Morgan about recent news, and interviews with activists, politicians

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, authors, actors and artists. The weekly hour was picked up by CBS Radio

CBS Radio was a radio broadcasting company and radio network operator owned by CBS Corporation and founded in 1928, with consolidated radio station groups owned by CBS and Westinghouse Broadcasting/Group W since the 1920s, and Infinity Broad ...

two weeks after its launch and is broadcast on CBS affiliate WJFK each Saturday. The program features commentary by Morgan about recent news, and interviews with activists, politicians

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, authors, actors and artists.

Activism

By 1962 Morgan had become active in theanti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to p ...

Left, and had also contributed articles and poetry to such Left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

and counter-culture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

journals as ''Liberation

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

'', '' Rat'', ''Win'', and '' The National Guardian''.

In the 1960s she became increasingly involved in social-justice movements, notably the civil-rights and anti-Vietnam war. In early 1967, she was active in the Youth International Party (known in the media as the "Yippies"), with Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponen ...

and Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner (April 9, 1932 – July 21, 2019) was an American author, journalist, and comedian. He was the founder, editor, and a frequent contributor to the freethought magazine ''The Realist'', first published in 1958. Krassner became a key ...

. However, tensions over sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers pri ...

within the YIP (and the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights ...

in general) came to a head when Morgan grew more involved in Women's Liberation and contemporary feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

.

In 1967, Morgan became a founding member of the short-lived New York Radical Women group. She was the key organizer of their September 1968 inaugural protest of the Miss America

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 17 and 25. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is now judged on competitors' talent performances and interviews. As ...

pageant in Atlantic City. Morgan wrote the Miss America protest

The Miss America protest was a demonstration held at the Miss America 1969 contest on September 7, 1968, attended by about 200 feminists and civil rights advocates. The feminist protest was organized by New York Radical Women and included putting ...

pamphlet ''No More Miss America!'', and that same year cofounded Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell

W.I.T.C.H., originally the acronym for Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, was the name of several related but independent feminist groups active in the United States as part of the women's liberation movement during the late 19 ...

(W.I.T.C.H.), a radical feminist group that used public street theater

Street theatre is a form of theatrical performance and presentation in outdoor public spaces without a specific paying audience. These spaces can be anywhere, including shopping centres, car parks, recreational reserves, college or university ...

(called "hexes" or "zaps") to call attention to sexism. Morgan designed the universal symbol of the women’s movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such iss ...

––the female symbol, a circle with a cross beneath, centered with a raised fist. The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a c ...

'' also credits her with first using the term "herstory

Herstory is a term for history written from a feminist perspective and emphasizing the role of women, or told from a woman's point of view. It originated as an alteration of the word "history", as part of a feminist critique of conventional his ...

" in print in her 1970 anthology ''Sisterhood is Powerful

''Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement'' is a 1970 anthology of feminist writings edited by Robin Morgan, a feminist poet and founding member of New York Radical Women. It is one of the first widel ...

''. Concerning the feminist organization W.I.T.C.H., Morgan wrote:

:The fluidity and wit of the witches is evident in the ever-changing acronym: the basic, original title was Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell

W.I.T.C.H., originally the acronym for Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, was the name of several related but independent feminist groups active in the United States as part of the women's liberation movement during the late 19 ...

..and the latest heard at this writing is Women Inspired to Commit Herstory."

With the royalties from her anthology ''Sisterhood Is Powerful'', Morgan founded the first feminist grant-giving foundation in the US: ''The Sisterhood Is Powerful Fund'', which provided seed money to many early women's groups throughout the 1970s and 1980s. She made a decisive break from what she described as the "male Left" when she led the women's takeover of the underground newspaper '' Rat'' in 1970, and listed the reasons for her break in the first women's issue of the paper, in her essay titled "Goodbye to All That." The essay gained notoriety in the press for naming specific sexist men and institutions in the Left. Decades later, during the Democratic primaries for the 2008 presidential race, Morgan wrote a fiery sequel to her original essay, titled "Goodbye To All That #2", in defense of Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

. The article quickly went viral on the internet for lambasting sexist rhetoric directed towards Clinton by the media.

In 1977, Morgan became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press

Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP) is an American nonprofit publishing organization that was founded in Washington, D.C. in 1972. The organization works to increase media democracy and strengthen independent media. Mo

Basic info ...

(WIFP). WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Morgan has traveled extensively across the United States and around the world to bring attention to cross-cultural sexism. She has met with and interviewed female rebel—army fighters in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Brazilian women activists in the slums/favelas of Rio

Rio or Río is the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Maltese word for "river". When spoken on its own, the word often means Rio de Janeiro, a major city in Brazil.

Rio or Río may also refer to:

Geography Brazil

* Rio de Janeiro

* Rio do Sul, a ...

, women organizers in the townships of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, and underground feminists in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Twice––in 1986 and 1989 she spent months in the Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

refugee camps in Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, and Gaza, to report on the conditions of women. Morgan has also spoken at universities and institutions in countries across Europe, the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

, and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, as well as in Australia, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, China, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Japan, Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is ma ...

, New Zealand, Pacific Island

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

nations, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

.

Over the years, Morgan has received numerous awards for her activism on women’s rights. The Feminist Majority Foundation

The Feminist Majority Foundation (FMF) is a non-profit organization headquartered in Arlington County, Virginia, whose stated mission is to advance non-violence and women's power, equality, and economic development. The name Feminist Majority come ...

named Robin Morgan "Woman of the Year" in 1990; she received the Warrior Woman Award for Promoting Racial Understanding from The Asian American Women's National Organization in 1992; in 2002 she received a Lifetime Achievement in Human Rights from Equality Now

Equality Now is a non-governmental organization founded in 1992 to advocate for the protection and promotion of the human rights of women and girls. Through a combination of regional partnerships, community mobilization and legal advocacy the or ...

, and in 2003 The Feminist Press

The Feminist Press (officially The Feminist Press at CUNY) is an American independent nonprofit literary publisher that promotes freedom of expression and social justice. It publishes writing by people who share an activist spirit and a belief in ...

gave her a "Femmy" Award for her "service to literature." She has also received the Humanist Heroine Award from The American Humanist Association in 2007.

;Limbaugh FCC incident

In March 2012 Morgan, along with her Women's Media Center co-founders Jane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress, activist, and former fashion model. Recognized as a film icon, Fonda is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Jane Fonda, various accolades including two ...

and Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

, wrote an open letter asking listeners to request that the U.S. Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains jurisdicti ...

(FCC) investigate the Rush Limbaugh–Sandra Fluke controversy, where Rush Limbaugh

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III ( ; January 12, 1951 – February 17, 2021) was an American conservative political commentator who was the host of '' The Rush Limbaugh Show'', which first aired in 1984 and was nationally syndicated on AM and FM r ...

referred to Sandra Fluke

Sandra Kay Fluke (, born April 17, 1981) is an American lawyer, women's rights activist, and representative to the Democratic Party of San Fernando Valley.

She first came to public attention when, in February 2012, Republican members of the Hou ...

as a "slut" and "prostitute" after she advocated for insurance coverage for contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

. They asked that stations licensed for public airwaves carrying Limbaugh be held accountable for contravening public interest as a continual promoter of hate speech

Hate speech is defined by the ''Cambridge Dictionary'' as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation". Hate speech is "usually thoug ...

against various disempowered and minority groups.

Sisterhood anthologies

In 1970, Morgan compiled, edited, and introduced the first

In 1970, Morgan compiled, edited, and introduced the first anthology

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs or excerpts by different authors.

In genre fiction, the term ''anthology'' typically cate ...

of feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

writings, ''Sisterhood is Powerful

''Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement'' is a 1970 anthology of feminist writings edited by Robin Morgan, a feminist poet and founding member of New York Radical Women. It is one of the first widel ...

''. The compilation included now-classic feminist essays by such activists as Naomi Weisstein, Kate Millett

Katherine Murray Millett (September 14, 1934 – September 6, 2017) was an American feminist writer, educator, artist, and activist. She attended Oxford University and was the first American woman to be awarded a degree with first-class honors ...

, Eleanor Holmes Norton

Eleanor Holmes Norton (born June 13, 1937) is an American lawyer and politician serving as a delegate to the United States House of Representatives, representing the District of Columbia since 1991. She is a member of the Democratic Party.

Ea ...

, Florynce Kennedy

Florynce Rae Kennedy (February 11, 1916 – December 21, 2000) was an American lawyer, radical feminist, civil rights advocate, lecturer and activist.

Early life

Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Missouri, to an African-American family. Her fat ...

, Frances M. Beal

Frances M. Beal, also known as Fran Beal, (born January 13, 1940, in Binghamton, New York) is a Black feminist and a peace and justice political activist. Her focus has predominantly been regarding women's rights, racial justice, anti-war and pea ...

, Joreen, Marge Piercy

Marge Piercy (born March 31, 1936) is an American progressive activist and writer. Her work includes '' Woman on the Edge of Time''; '' He, She and It'', which won the 1993 Arthur C. Clarke Award; and ''Gone to Soldiers'', a New York Times Best ...

, Lucinda Cisler and Mary Daly, as well as historical documents including the N.O.W. Bill of Rights, excerpts from the SCUM Manifesto

''SCUM Manifesto'' is a radical feminist manifesto by Valerie Solanas, published in 1967. It argues that men have ruined the world, and that it is up to women to fix it. To achieve this goal, it suggests the formation of SCUM, an organization de ...

, the Redstockings

Redstockings, also known as Redstockings of the Women's Liberation Movement, is a radical feminist nonprofit that was founded in January 1969 in New York City, whose goal is "To Defend and Advance the Women's Liberation Agenda". The group's name ...

Manifesto, historical documents from W.I.T.C.H.

''W.I.T.C.H.'' (stylised as ''W.i.t.c.h.'') is an Italian fantasy Disney comics series created by Elisabetta Gnone, Alessandro Barbucci, and Barbara Canepa. The series features a group of five teenage girls who become the guardians of the class ...

, and a germinal statement from the Black Women’s Liberation Group of Mount Vernon. It also included what Morgan called "verbal karate": useful quotes and statistics about women. The anthology was cited by the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress) ...

as one of the “New York Public Library's Books of the 0thCentury”. Morgan established the first American feminist grant-giving organization, The Sisterhood Is Powerful Fund, with the royalties from ''Sisterhood Is Powerful

''Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement'' is a 1970 anthology of feminist writings edited by Robin Morgan, a feminist poet and founding member of New York Radical Women. It is one of the first widel ...

''. However, the anthology was banned in Chile, China, and South Africa.

Her follow-up volume in 1984, '' Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology'', compiled articles about women in over seventy countries. That same year she founded the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, notable for being the first international feminist think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-govern ...

. Repeatedly refusing the post of president, she was elected secretary of the organization from 1989 to 1993, was VP from 1993 to 1997, and after serving on the advisory board, finally agreed to become president in 2004. A third volume, '' Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium '' in 2003, was a collection of articles mostly by well-known feminists, both young and "vintage," in a retrospective on and future blueprint for the feminist movement. It was compiled, edited, and with an introduction by Morgan, and Morgan wrote "To Vintage Feminists" and "To Younger Women", which were both included in the anthology as Personal Postscripts.

Journalism

Morgan's articles, essays, reviews, interviews, political analyses, and investigative journalism have appeared widely in such publications as ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'', ''Broadsheet

A broadsheet is the largest newspaper format and is characterized by long vertical pages, typically of . Other common newspaper formats include the smaller Berliner and tabloid–compact formats.

Description

Many broadsheets measure roughly ...

'', ''Chrysalis

A pupa ( la, pupa, "doll"; plural: ''pupae'') is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation between immature and mature stages. Insects that go through a pupal stage are holometabolous: they go through four distinct stages in thei ...

'', ''Essence

Essence ( la, essentia) is a polysemic term, used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property or set of properties that make an entity or substance what it fundamentally is, and which it has by necessity, and without which it ...

'', '' Everywoman'', ''The Feminist Art Journal

''The Feminist Art Journal'' was an American magazine, published quarterly from 1972 to 1977. It was the first stable, widely read journal covering feminist art. By the time the final publication was produced, ''The Feminist Art Journal'' had a cir ...

'', ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'' (US), ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'' (UK), ''The Hudson Review

''The Hudson Review'' is a quarterly journal of literature and the arts.

History

It was founded in 1947 in New York, by William Arrowsmith, Joseph Deericks Bennett, and George Frederick Morgan. The first issue was introduced in the spring of 194 ...

'', the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'', ''Ms.

Ms. (American English) or Ms (British English; normally , but also , or when unstressed)''Oxford English Dictionary'' online, Ms, ''n.2''. Etymology: "An orthographic and phonetic blend of Mrs ''n.1'' and miss ''n.2'' Compare mizz ''n.'' The pr ...

'', ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'', ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', ''Off Our Backs

''Off Our Backs'' (stylized in all lowercase; ''oob'') was an American radical feminist periodical that ran from 1970 to 2008. It began publishing on February 27, 1970, with a twelve-page tabloid first issue. From 2002 the editors adapted it i ...

'', ''Pacific Ways'', ''The Second Wave'', ''Sojourner'', ''The Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture paper, known for being the country's first alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock, and Norman Mailer, the ''Voice'' began as a platform for the cr ...

'', ''The Voice of Women'', and various United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

periodicals, etc.

Articles and essays have also appeared in reprint in international media, in English across the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

, and in translation in 13 languages in Europe, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

.

Morgan has served as a contributing editor to ''Ms.

Ms. (American English) or Ms (British English; normally , but also , or when unstressed)''Oxford English Dictionary'' online, Ms, ''n.2''. Etymology: "An orthographic and phonetic blend of Mrs ''n.1'' and miss ''n.2'' Compare mizz ''n.'' The pr ...

'' magazine for many years, receiving the Front Page Award for Distinguished Journalism for her cover story titled "The First Feminist Exiles from the USSR" in 1981. She served as the magazine's editor-in-chief from 1989 to 1994, re-launching it as an ad-free, international bimonthly publication in 1991. This earned her a series of awards, including the award for Editorial Excellence by ''Utne Reader'' in 1991, and the Exceptional Merit in Journalism Award by the National Women's Political Caucus

The National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC), or the Caucus, describes itself as a multi-partisan grassroots organization in the United States dedicated to recruiting, training, and supporting women who seek elected and appointed offices at all ...

. Morgan resigned her post in 1994 to become Consulting Global Editor of the magazine, which she remains to this day.

Morgan has written for online audiences and blogged frequently. Among her best known articles are "Letters from Ground Zero" (written and posted after the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

in 2001 — which went viral), "Goodbye To All That #2", "Women of the Arab Spring", "When Bad News is Good News: Notes of a Feminist News Junkie", "Manhood and Moral Waivers", and "Faith Healing: A Modest Proposal on Religious Fundamentalism". Her online work is hosted in the archives of the Women's Media Center.

Authorship

Robin Morgan has published 21 books, including works of poetry, fiction, and the now-classic anthologies ''Sisterhood Is Powerful,'' ''Sisterhood Is Global'', and ''Sisterhood Is Forever''. Well before she was known as a feminist leader, literary magazines published her as a serious poet. According to a 1972 review of her first book of poems, ''Monster'', in ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'': " hese poemsestablish Morgan as a poet of considerable means. There is a savage elegance, a richness of vocabulary, a thrust and steely polish..... A powerful, challenging book." In 1979 Morgan received a National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

Creative Writing Fellowship in poetry, then held a writing residency at the arts colony Yaddo

Yaddo is an artists' community located on a estate in Saratoga Springs, New York. Its mission is "to nurture the creative process by providing an opportunity for artists to work without interruption in a supportive environment.". On March&nbs ...

the following year. During this time she worked on a cycle of verse plays.

Morgan’s poetry collections include ''A Hot January: Poems 1996–1999'' (W. W. Norton, 1999), ''Depth Perception: New Poems and a Masque'' (Doubleday, 1994), ''Upstairs in the Garden: Poems Selected and New 1968–1988'' (W. W. Norton, 1990), ''Death Benefits'' (Copper Canyon Press, 1981), ''Lady of the Beasts'' (Random House, 1976), and ''Monster'' (Random House, 1972). Of the book A ''Hot January'', Alice Walker

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and social activist. In 1982, she became the first African-American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was awa ...

wrote: "Morgan proves that exquisite poetry can be the most surprising gift of grief. A volume as proud, fierce, vulnerable, and brave as the poet herself." A review of ''Upstairs in the Garden'', noted: "As a vindication and celebration of the female experience, these inventive poems successfully wed feminist rhetoric with vivid imagery and sensitivity to the music of language." Two books of poems, ''Lady of the Beasts'' and ''Depth Perception'', earned reviews in ''Poetry Magazine

''Poetry'' (founded as ''Poetry: A Magazine of Verse'') has been published in Chicago since 1912. It is one of the leading monthly poetry journals in the English-speaking world. Founded by Harriet Monroe, it is now published by the Poetry Foundati ...

'' with critic Jay Parini

Jay Parini (born April 2, 1948) is an American writer and academic. He is known for novels, poetry, biography, screenplays and criticism. He has published novels about Leo Tolstoy, Walter Benjamin, Paul the Apostle, and Herman Melville.

Early l ...

stating that "Robin Morgan will soon be regarded as one of our first-ranking poets."

Morgan had published three books of fiction as of 2015. Her debut novel was the semi-autobiographical ''Dry Your Smile'' (published by Doubleday & Company

Doubleday is an American publishing company. It was founded as the Doubleday & McClure Company in 1897 and was the largest in the United States by 1947. It published the work of mostly U.S. authors under a number of imprints and distributed th ...

, 1987), followed by ''The Mer-Child: A Legend for Children and Other Adults'' (published by The Feminist Press

The Feminist Press (officially The Feminist Press at CUNY) is an American independent nonprofit literary publisher that promotes freedom of expression and social justice. It publishes writing by people who share an activist spirit and a belief in ...

at City University of New York, 1991). Her most recent work of fiction is a historical novel titled ''The Burning Time'' (Melville House Books, 2006), set in the 14th century, based on court records of the first witchcraft trial in Ireland. ''The Burning Time'' was placed on the Recommended Quality Fiction List of 2007 by the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world, with 49,727 members ...

, in addition to being the 2006 Paperback Pick by Book Sense (The American Booksellers Association).

Morgan has compiled, edited, and introduced several influential anthologies: ''Sisterhood Is Powerful: The Women’s Liberation Anthology'' (1970), ''Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology'' (1984), and ''Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women’s Anthology for a New Millennium'' (2003). She has herself written non-fiction, including ''Going Too Far'' (1978), ''The Anatomy of Freedom'' (1984), ''The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism'' (1989), ''The Word of a Woman'' (1994), and ''Saturday’s Child: A Memoir'' (2001). One of the most widely translated of Morgan’s books and a best-seller, ''The Demon Lover'' is a commentary on the psychological and political roots of terrorism, and ''New York Times Book Review'' called it "Important...compelling....organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

is intense and at times magnificent." Her most recently published book of non-fiction is ''Fighting Words: A Tool Kit for Combating the Religious Right'' (2006).

Organizations

The Sisterhood Is Global Institute

In 1984, Morgan, together with the lateSimone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, and even ...

of France, and women from 80 other countries, founded The Sisterhood Is Global Institute (SIGI), an international non-profit NGO with consultative status to the United Nations, which has for three decades functioned as the world’s first feminist think-tank. The Institute has played a leading policy-formulation, strategic, and activist role in the evolution of the international Women’s Movement. SIGI has also developed a global communications network through which an umbrella of NGO interest, advice, contacts, and support is collectively mobilized to empower the global women’s movement.

Among its many activities, the Institute pioneered the first Urgent Acton Alerts regarding women’s rights; the first Global Campaign To Make Visible Women’s Unpaid Labor In National Accounts; and the first Women’s Rights Manuals For Muslim Societies (in 12 languages). Its most recent project is Donor Direct Action (donordirectaction.org), which links front-line women’s rights activists around the world to money, visibility, and popular support: minimum bureaucracy, maximum impact.

Women’s Media Center

In 2005, Morgan co-founded the non-profit progressive organization, The Women’s Media Center with her friends actor/activistJane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress, activist, and former fashion model. Recognized as a film icon, Fonda is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Jane Fonda, various accolades including two ...

, and activist Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

. The focus of the organization is to make women powerful and visible in the media.

Lectures and professorships

An invited speaker at numerous universities in North America, Morgan has traveled—as organizer, speaker, journalist—across North America, Europe, and the Middle East to Australia, Brazil, the Caribbean, Central America, China, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Nepal, New Zealand, Pacific Island nations, the Philippines, and South Africa. She has also been a Guest Professor or Scholar in Residence at a variety of academic institutions. She was Guest Chair for Feminist Studies at theNew College of Florida

New College of Florida is a public liberal arts college in Sarasota, Florida. It was founded in 1960 as a private institution known simply as New College, spent several years merged into the University of South Florida, and in 2001 became an aut ...

in 1971; a visiting professor at The Center for Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture at Rutgers University

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and was ...

in 1987; a Distinguished Visiting Scholar in Residence for Literary and Cultural Studies at the University of Canterbury

The University of Canterbury ( mi, Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha; postnominal abbreviation ''Cantuar.'' or ''Cant.'' for ''Cantuariensis'', the Latin name for Canterbury) is a public research university based in Christchurch, New Zealand. It was ...

, Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon Rive ...

, New Zealand in 1989; a Visiting Professor in residence at the University of Denver

The University of Denver (DU) is a private research university in Denver, Colorado. Founded in 1864, it is the oldest independent private university in the Rocky Mountain Region of the United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Univ ...

, Colorado in 1996; and Visiting Professor at the Center for Documentation on Women at University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in contin ...

, Italy, in 1996. She was awarded an Honorary Degree as a Doctor of Humane Letters

The degree of Doctor of Humane Letters (; DHumLitt; DHL; or LHD) is an honorary degree awarded to those who have distinguished themselves through humanitarian and philanthropic contributions to society.

The criteria for awarding the degree differ ...

by the University of Connecticut at Storrs

The University of Connecticut (UConn) is a public land-grant research university in Storrs, Connecticut, a village in the town of Mansfield. The primary 4,400-acre (17.8 km2) campus is in Storrs, approximately a half hour's drive from Hart ...

in 1992. The Robin Morgan Papers, a collection that documents the personal, political, and professional aspects of Morgan's life, are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University

Duke University is a private research university in Durham, North Carolina. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1892. In 1924, tobacco and electric power industrialist Jam ...

. They date from the 1940s to the present.

Criticism

Robin Morgan has been arrested, and has received death threats from both the Right and the Left because of her activism. According to a ''New Yorker

New Yorker or ''variant'' primarily refers to:

* A resident of the State of New York

** Demographics of New York (state)

* A resident of New York City

** List of people from New York City

* ''The New Yorker'', a magazine founded in 1925

* '' The ...

'' magazine article published in the aftermath of Morgan's essay "Goodbye to All That" (#2) going viral on the Internet, "At five feet tall Morgan is, not for the first time, the little woman who has started a big war." In her original essay, "Goodbye to All That" (1970), Morgan bade adieu to "the dream that being in the leadership collective will get you anything but gonorrhea," referring to the "male Left." She also asserted that Charles Manson

Charles Milles Manson (; November 12, 1934November 19, 2017) was an American criminal and musician who led the Manson Family, a cult based in California, in the late 1960s. Some of the members committed a series of nine murders at four loca ...

was "only the logical extreme of the normal American male’s fantasy."

Two years later, Morgan published the poem "Arraignment", in which she openly accused Ted Hughes

Edward James "Ted" Hughes (17 August 1930 – 28 October 1998) was an English poet, translator, and children's writer. Critics frequently rank him as one of the best poets of his generation and one of the twentieth century's greatest wri ...

of the battery and murder of Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath (; October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. She is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for two of her published collections, '' Th ...

. There were lawsuits, Morgan's 1972 book ''Monster'' which contained that poem was banned, and underground, pirated feminist editions of it were published.

As the leading organizer of the 1968 protest of the Miss America Pageant, " No More Miss America!", Morgan attacked the pageant’s "ludicrous 'beauty' standards and also accused the pageant of being racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

, since at that time no African American woman had been a contestant. In addition––according to Morgan––in sending pageant winners to entertain troops in Vietnam, the women served as "death mascots" in an immoral war. Morgan asked, "Where else could one find such a perfect combination of American values -- racism, militarism, capitalism -- all packaged in one 'ideal' symbol, a woman."

Another controversial quote is from her 1978 book, Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist, where she stated: "I feel that "man-hating" is an honorable and viable political act, that the oppressed have a right to class-hatred against the class that is oppressing them."

Morgan famously walked off ''The Tonight Show'' in 1969 when it screened vintage footage of her as a child actor while she was trying to speak seriously about the first national march against rape. Of the incident, she has been quoted as saying: "Imagine talking about such a subject and having it trivialized like that." In 1974, with her phrase "Pornography is the theory, and rape is the practice" (from her essay "Theory and Practice: Pornography and Rape"), she became a central figure on one of the divisive issues in feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, particularly among anti-pornography feminists in Anglophone countries.

In 1973, Robin Morgan gave the keynote speech at the West Coast Lesbian Conference, in which she criticized Beth Elliott

Beth Elliott (born 1950) is an American trans lesbian folk singer, activist, and writer. In the early 1970s Elliot was involved with the Daughters of Bilitis and the West Coast Lesbian Conference in California. She became the centre of a controve ...

, a performer and organizer of the conference, for being a transgender woman. In this speech she referred to Elliott as a "transsexual male" and used male pronouns throughout, charging her with being "an opportunist, an infiltrator, and a destroyer-with the mentality of a rapist." At the end of her speech she called for a vote on ejecting Elliott, with over two-thirds voting to allow her to remain, however the minority threatened to disrupt the conference and Elliott chose to leave after her performance to avoid this. The event demonstrated the high tension surrounding transgender women's involvement in the women's movement of the 1970s.

Personal life

Robin Morgan grew up in New York, first inMount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

, and later in Manhattan, on Sutton Place. She graduated from The Wetter School in Mount Vernon, in 1956, and was privately tutored from then until 1959. She published her first serious poetry in literary magazines at age 17.

In an article published in the Jewish Women's Archive, Morgan reveals she is of Jewish ancestry, but identifies her religion as Wiccan and/or atheist. She is quoted as saying, "When compelled to define myself specifically in ethnic terms—I have described myself as being European American of Ashkenazic (with a touch of Sephardic) Jewish ancestry. I respect and understand the desire of others to affirm their ethnic roots as central to their identities, but while I’m quite proud of mine, I feel they’re just not particularly central to my identity. I am deeply opposed to all patriarchal religions, including though not limited to Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

." Morgan continues to tackle topics such as religion, politics and sex in fiery commentaries on her radio show "WMC Live with Robin Morgan."

Today Robin Morgan lives in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Blake Morgan, her son with ex-husband Kenneth Pitchford, is a musician, recording artist, and founder of New York-based record company ECR Music Group.

In 2000 Norton published Morgan’s memoir, ''Saturday's Child'', in which she wrote candidly about "the shadowy circumstances of her birth; a lifelong, impassioned, love-hate relationship with her mother; her years as a famous child actor and her fight to escape show business to become a serious writer; her marriage to a fiery bisexual poet and how motherhood transformed her life; her years in the civil rights movement, the New Left, and counterculture; her emergence a leader of global feminism; and her love affairs with women as well as men," according to ''BookNews.com''. In her book, "her passion for writing, especially poetry, is vividly conveyed, as is her love and respect for her son, born in 1969," according to ''The New York Times Book Review''.

In April 2013, Morgan announced publicly that she had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, discussing the diagnosis on her radio show ''WMC Live with Robin Morgan'', revealing that she had been diagnosed in 2010, but that her quality of life was thus far "normal." Since her diagnosis, Morgan has become active with the Parkinson's Disease Foundation

The Parkinson's Foundation is a national organization that funds research and provides educational resources to Parkinson’s disease patients and caregivers. The Parkinson's Foundation was established in 2016 through the merger of the National P ...

(PDF), completing training to become part of the organization's Parkinson's Advocates in Research initiative. In 2014 she was the catalyst and took a leadership role in PDF's new Women and PD initiative, which will seek to better serve women impacted by Parkinson's disease by understanding and resolving gender inequalities in PD research, treatment, and caregiver support. Morgan has also written new poetry inspired by her battle with the disease, and performed a reading of some of the poems as a TED Talk, at the TEDWomen 2015 conference.

Birth and parents

Her mother, Faith Berkeley Morgan, traveled from her New York residence to Florida to give birth, in order to avoid public scrutiny for her unmarried status. Robin's father, a medical doctor named Mates Morgenstern, did not accompany pregnant Faith on her trip. Until Robin Morgan was 13 years old, her mother Faith claimed that Robin's father had been killed in World War II. However, Robin overheard conversations between her mother and aunt suggesting her father was alive. When she confronted her mother, Faith changed her story to assert that Robin's father had escaped from one Nazi concentration camp after another, and that she had saved his life by sponsoring his immigration to the United States where he had no family. Not until several years later, did Robin get proof that this was also a lie. Robin Morgan learned the truth, both about her father, who was still alive, and how old she really was, early in 1961. Now a young woman, no longer working in show business, Robin found a listing for the medical practice of an obstetrician Dr. Mates Morgenstern in theNew Brunswick, New Jersey

New Brunswick is a city in and the seat of government of Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. He also told Robin, during their conversation in his medical office, that she in fact was born on January 29, 1941, exactly one year earlier than she thought, and disclosed the copy of her original birth certificate, that he had stored in his office. In order to conceal the out-of-wedlock birth, Faith Morgan had asked her Florida obstetrician to sign an affidavit stating that the birth took place on January 29, 1942.

During the conversation in his office, Morgenstern told his daughter that he first met her mother after his arrival in the United States, more than a year before the United States entered World War II, and that she had had nothing to do with his immigration. He added that he had known Faith only briefly and claimed that she had fantasized their relationship as more important than it was. By the time Robin Morgan met her father he had married and had two sons with a woman he had known since they were both children in Austria. Having been separated by the war, they resumed their relationship after she arrived in the United States not long after Robin was born, which probably also added to Morgenstern's decision to abandon Faith and their daughter.

Morgan only met her father once more, in February 1965 when he invited her and her husband to his New Jersey home. Morgenstern did not want his sons to know that they had a half-sister and Morgan acceded to his request that they tell his two sons that she was "the daughter of an old friend." She refused to do so again, however, and never met him or her two half-brothers again.

Morgan describes the two encounters that she had with her biological father in her autobiography, ''Saturday's Child: A Memoir''.

When Faith Morgan developed

A Woman's Creed

' (pamphlet), The Sisterhood Is Global Institute *2001: ''Saturday's Child: A Memoir'' (

The politics of sado-masochistic fantasies

in *

Light bulbs, radishes and the politics of the 21st century

in

Womens Media Center

The Sisterhood is Global Institute

*

Ms. Magazine

'

Papers of Robin Morgan, 1929–1991 (inclusive), 1968–1986 (bulk).Schlesinger Library

Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Robin Morgan

Video produced by Makers: Women Who Make America * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Robin 1941 births Living people Jewish American atheists American feminist writers Jewish American journalists Jewish feminists American abortion-rights activists American women's rights activists Anti-pornography feminists American Wiccans People from Lake Worth Beach, Florida Writers from Mount Vernon, New York American child actresses Radical feminists Atheist feminists Wiccan feminists 20th-century American novelists 21st-century American novelists 20th-century American poets 20th-century American women writers 21st-century American women writers American women poets American women novelists 21st-century American poets Activists from New York (state) 20th-century atheists 21st-century atheists American political writers Novelists from New York (state) Wiccan novelists Modern pagan poets Columbia University alumni Actors from Mount Vernon, New York Yippies American women non-fiction writers 21st-century American non-fiction writers BBC 100 Women Wiccans of Jewish descent New York Radical Women members

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms beco ...

, in her early 60s, Robin telephoned her biological father to let him know. When she asked if he wanted to say goodbye, he declined. During Faith's illness, her life savings, which consisted of the money Robin had earned in her radio and television career – by then a six-figure sum that had accumulated in the bank – was stolen, by her two elderly home-caregivers. Robin Morgan discovered this but ultimately chose not to press charges.

Filmography

;1940s *''Citizen Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini'' (playing Francesca S. Cabrini as a child) *''The Little Robin Morgan Show'' as herself ( WOR radio show) *''Juvenile Jury

''Juvenile Jury'' was an American children's game show that originally ran on NBC from April 3, 1947, to August 1, 1954. It was hosted by Jack Barry and featured a panel of children aged ten or less giving advice to solve the problems of other ch ...

'' as herself

;1950s

*''Mama

Mama(s) or Mamma or Momma may refer to:

Roles

*Mother, a female parent

* Mama-san, in Japan and East Asia, a woman in a position of authority

*Mamas, a name for female associates of the Hells Angels

Places

* Mama, Russia, an urban-type settlemen ...

'' as Dagmar Hansen

*'' Kraft Television Theatre's Alice in Wonderland'' (as Alice)

*'' Mr. I-Magination'' (as self)

*''Tales of Tomorrow

''Tales of Tomorrow'' is an American anthology science fiction series that was performed and broadcast live on ABC from 1951 to 1953. The series covered such stories as ''Frankenstein'' starring Lon Chaney Jr., '' 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea'' ...

'' (starring as Lily Massner)

*''Kiss and Tell'' TV Special (starring as Corliss Archer, 1956)

*Other videos and kinescopes

Kinescope , shortened to kine , also known as telerecording in Britain, is a recording of a television program on motion picture film, directly through a lens focused on the screen of a video monitor. The process was pioneered during the 1940s ...

in the Robin Morgan Collection at the Paley Center for Media