Robert Morris (merchant) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Morris Jr. (January 20, 1734May 8, 1806) was an English-born merchant and a

Greenway arranged for Morris to become an apprentice at the shipping and banking firm of Philadelphia merchant

Greenway arranged for Morris to become an apprentice at the shipping and banking firm of Philadelphia merchant

In 1781, Morris purchased a home on

In 1781, Morris purchased a home on

With their plans to call a new state constitutional convention frustrated by Joseph Reed and others, Morris and

With their plans to call a new state constitutional convention frustrated by Joseph Reed and others, Morris and

In the midst of the American Revolutionary War, U.S. government finances fell into a poor state as Congress lacked the power to raise revenue and the states largely refused to furnish funding. Without a mechanism for raising revenue, Congress repeatedly issued

In the midst of the American Revolutionary War, U.S. government finances fell into a poor state as Congress lacked the power to raise revenue and the states largely refused to furnish funding. Without a mechanism for raising revenue, Congress repeatedly issued

As of January 1, 1783, the public debt was $42 million of which 18.77 percent was foreign debt and 81.23 percent was owned at home.Financial History of the United States. p. 317

/ref>

In a report to the President of Congress Morris wrote: *Domestic Debt...$35,327,769 of which *Loan Certificates...$11,463,802 ith two years interest loan due $877,828*Army Debt...$635,618.00 The rest being unliquidated debts, etc., interest. At roughly the same time, Morris and others in Philadelphia learned that the United States and Britain had signed a preliminary peace agreement, bringing an unofficial end to the Revolutionary War. Congress approved a furlough of the Continental Army soldiers, subject to recall in case hostilities broke out once again. Morris distributed "Morris notes" to the remaining soldiers, but many soldiers departed for their homes rather than waiting for the notes. After a mutiny over pay broke out in Pennsylvania, Congress voted to leave Philadelphia and establish a provincial capital in In November 1784, Morris resigned from his government positions. Rather than finding a successor for Morris, Congress established the three-member Board of Treasury, consisting of Arthur Lee, William Livingston, and Samuel Osgood. In 1778–1779 Morris had attempted to strengthen out the accounts of the old Commercial Committee but had to give it up; he stated in answer to Paine "the accounts of Willing and Morris with the committee had been partially settled, but were still partially open, because the transactions could not be closed up." The Treasury Board elected in 1794-1795 those old accounts were brought to a settlement—a June 1796 entry in the Treasury debt against Morris for $93,312.63. Morris would explain in 1800 in debtors' prison that in fact the debt was due not just to himself but also his partners John Ross and

In November 1784, Morris resigned from his government positions. Rather than finding a successor for Morris, Congress established the three-member Board of Treasury, consisting of Arthur Lee, William Livingston, and Samuel Osgood. In 1778–1779 Morris had attempted to strengthen out the accounts of the old Commercial Committee but had to give it up; he stated in answer to Paine "the accounts of Willing and Morris with the committee had been partially settled, but were still partially open, because the transactions could not be closed up." The Treasury Board elected in 1794-1795 those old accounts were brought to a settlement—a June 1796 entry in the Treasury debt against Morris for $93,312.63. Morris would explain in 1800 in debtors' prison that in fact the debt was due not just to himself but also his partners John Ross and

After leaving office, Morris once again devoted himself to business, but state and federal politics remained a factor in his life. After the Pennsylvania legislature stripped the Bank of North America of its charter, Morris won election to the state legislature and helped restore the bank's charter. Meanwhile, the United States suffered a sustained recession after the end of the Revolutionary War, caused by the lingering debt burden and new restrictions on trade imposed by the European powers. Some members of Congress, including those on the Board of Treasury, continued to favor amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but the states still refused to authorize major changes to the Articles.

In 1786, Morris was one of five Pennsylvania delegates selected to attend the Annapolis Convention (1786), Annapolis Convention, where delegates discussed ways to reform the Articles of Confederation. Though Morris ultimately declined to attend the convention, the delegates convinced Congress to authorize a convention in Philadelphia in May 1787 to amend the Articles. The Pennsylvania state legislature sent a delegation consisting of Morris, James Wilson, Gouverneur Morris, George Clymer,

After leaving office, Morris once again devoted himself to business, but state and federal politics remained a factor in his life. After the Pennsylvania legislature stripped the Bank of North America of its charter, Morris won election to the state legislature and helped restore the bank's charter. Meanwhile, the United States suffered a sustained recession after the end of the Revolutionary War, caused by the lingering debt burden and new restrictions on trade imposed by the European powers. Some members of Congress, including those on the Board of Treasury, continued to favor amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but the states still refused to authorize major changes to the Articles.

In 1786, Morris was one of five Pennsylvania delegates selected to attend the Annapolis Convention (1786), Annapolis Convention, where delegates discussed ways to reform the Articles of Confederation. Though Morris ultimately declined to attend the convention, the delegates convinced Congress to authorize a convention in Philadelphia in May 1787 to amend the Articles. The Pennsylvania state legislature sent a delegation consisting of Morris, James Wilson, Gouverneur Morris, George Clymer,

In the country's 1788–89 United States presidential election, first presidential election, Washington was elected as the President of the United States. Washington offered the position of United States Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of the Treasury to Morris, but Morris declined the offer, instead suggesting Alexander Hamilton for the position. In the Senate, Morris pressed for many of the same policies he had sought as Superintendent of Finance: a federal tariff, a national bank, a federal mint, and the funding of the national debt. Congress agreed to implement the Tariff of 1789, which created a uniform impost on goods carried by foreign ships into American ports, but many other issues lingered into 1790. Among those issues were the site of the national capital and the fate of state debts. Morris sought the return of the nation's capital to Philadelphia and the federal assumption of state debts. Morris defeated Maclay's proposal to establish the capital in Pennsylvania at a site on the Susquehanna River located several miles west of Philadelphia, but James Madison defeated Morris's attempt to establish the capital just outside of Philadelphia.

Morris's 1781 "Report On Public Credit" supplied the basis for Hamilton's ''First Report on the Public Credit'', which Hamilton submitted in 1790. Hamilton proposed to fully fund all federal debts and assume all state debts, and to pay for those debts by issuing new federal bonds. Hamilton argued that these measures would restore confidence in public credit and help to revitalize the economy, but opponents attacked his proposals as unfairly beneficial to the speculators who had purchased many of the government's debt certificates. Morris supported Hamilton's economic proposals, but the two differed on the site of the federal capital, as Hamilton wanted to keep it in New York. In June 1790, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson convinced Morris, Hamilton, and Madison to agree to a compromise in which the federal government assumed state debts, while a new federal capital would be established on the Potomac River; until construction of that capital was completed, Philadelphia would serve as the nation's temporary capital. With the backing of all four leaders, the Compromise of 1790, as it became known, was approved by Congress. That same year, Morris and Maclay helped secure Pennsylvania's control of the Erie Triangle, which provided the state with access to the Great Lakes.

In the early 1790s, the country became increasingly polarized between the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson and Madison, and the Federalist Party, led by Hamilton. Though Morris was less focused on politics after the Compromise of 1790, he supported most of Hamilton's policies and aligned with the Federalist Party. Morris especially supported Hamilton's proposal for the establishment of a History of central banking in the United States, national bank. Despite the opposition of Madison and other Southern leaders, Congress approved the establishment of the First Bank of the United States in 1791. While Morris served in Congress, a new political elite emerged in Philadelphia. These new leaders generally respected Morris, but most did not look to him for leadership. With Morris playing little active role, they called a convention that revised the state constitution that included many of the alterations that Morris had long favored, including a bicameral legislature, a state governor with the power to veto bills, and a judiciary with life tenure.

In the country's 1788–89 United States presidential election, first presidential election, Washington was elected as the President of the United States. Washington offered the position of United States Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of the Treasury to Morris, but Morris declined the offer, instead suggesting Alexander Hamilton for the position. In the Senate, Morris pressed for many of the same policies he had sought as Superintendent of Finance: a federal tariff, a national bank, a federal mint, and the funding of the national debt. Congress agreed to implement the Tariff of 1789, which created a uniform impost on goods carried by foreign ships into American ports, but many other issues lingered into 1790. Among those issues were the site of the national capital and the fate of state debts. Morris sought the return of the nation's capital to Philadelphia and the federal assumption of state debts. Morris defeated Maclay's proposal to establish the capital in Pennsylvania at a site on the Susquehanna River located several miles west of Philadelphia, but James Madison defeated Morris's attempt to establish the capital just outside of Philadelphia.

Morris's 1781 "Report On Public Credit" supplied the basis for Hamilton's ''First Report on the Public Credit'', which Hamilton submitted in 1790. Hamilton proposed to fully fund all federal debts and assume all state debts, and to pay for those debts by issuing new federal bonds. Hamilton argued that these measures would restore confidence in public credit and help to revitalize the economy, but opponents attacked his proposals as unfairly beneficial to the speculators who had purchased many of the government's debt certificates. Morris supported Hamilton's economic proposals, but the two differed on the site of the federal capital, as Hamilton wanted to keep it in New York. In June 1790, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson convinced Morris, Hamilton, and Madison to agree to a compromise in which the federal government assumed state debts, while a new federal capital would be established on the Potomac River; until construction of that capital was completed, Philadelphia would serve as the nation's temporary capital. With the backing of all four leaders, the Compromise of 1790, as it became known, was approved by Congress. That same year, Morris and Maclay helped secure Pennsylvania's control of the Erie Triangle, which provided the state with access to the Great Lakes.

In the early 1790s, the country became increasingly polarized between the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson and Madison, and the Federalist Party, led by Hamilton. Though Morris was less focused on politics after the Compromise of 1790, he supported most of Hamilton's policies and aligned with the Federalist Party. Morris especially supported Hamilton's proposal for the establishment of a History of central banking in the United States, national bank. Despite the opposition of Madison and other Southern leaders, Congress approved the establishment of the First Bank of the United States in 1791. While Morris served in Congress, a new political elite emerged in Philadelphia. These new leaders generally respected Morris, but most did not look to him for leadership. With Morris playing little active role, they called a convention that revised the state constitution that included many of the alterations that Morris had long favored, including a bicameral legislature, a state governor with the power to veto bills, and a judiciary with life tenure.

Morris refocused on his trading concerns after leaving office as Superintendent of Finance, seeking especially to expand his role in the tobacco trade. He began suffering from financial problems in the late 1780s after a business partner mistakenly refused to honor bills issued by Morris, causing him to default on a loan.

In 1784 Morris was part of a syndicate that backed the sailing of the Empress of China (1783) for the China trade. As part of the effort to repay France for loans that financed the war, Morris contracted to supply 20,000 hogsheads of tobacco annually to France beginning in 1785. Shortly after these contracts were signed, Ambassador Thomas Jefferson took it upon himself to interfere with these arrangements and that brought about the collapse of the tobacco market.Ironically it was James Swan (financier) who on July 9 1795 managed to do something Morris had been unable to do-the entire U.S. National debt to France of $2,024,899 was payed in full.The United States no longer owed money to foreign governments, although it continued to owe money to private investors both in the United States and in Europe. This allowed the young United States to place itself on a sound financial footing.

Morris refocused on his trading concerns after leaving office as Superintendent of Finance, seeking especially to expand his role in the tobacco trade. He began suffering from financial problems in the late 1780s after a business partner mistakenly refused to honor bills issued by Morris, causing him to default on a loan.

In 1784 Morris was part of a syndicate that backed the sailing of the Empress of China (1783) for the China trade. As part of the effort to repay France for loans that financed the war, Morris contracted to supply 20,000 hogsheads of tobacco annually to France beginning in 1785. Shortly after these contracts were signed, Ambassador Thomas Jefferson took it upon himself to interfere with these arrangements and that brought about the collapse of the tobacco market.Ironically it was James Swan (financier) who on July 9 1795 managed to do something Morris had been unable to do-the entire U.S. National debt to France of $2,024,899 was payed in full.The United States no longer owed money to foreign governments, although it continued to owe money to private investors both in the United States and in Europe. This allowed the young United States to place itself on a sound financial footing.

In 1787, Morris was sued in Virginia by Carter Braxton for £28,257; the lawsuit continued for eight years before commissioners were appointed, then Morris appealed. Finally Virginia's Court of Appeals led by Edmund Pendleton decided mostly in favor of Braxton before Morris was forced into bankruptcy by his own continued land speculations (although Morris as late as 1800 believed he should have won £20,000). Morris became increasingly fixated on land speculation, reaching his first major real estate deal in 1790 when he acquired much of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase in western New York. He realized a substantial profit the following year when he sold the land to The Pulteney Association, a group of British land speculators led by Sir William Pulteney, 5th Baronet, Sir William Johnstone Pulteney. Morris used the money from this sale to purchase the remainder of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase, then turned around and sold much of that land to the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch land speculators. These early successes encouraged Morris to pursue greater profits through increasingly large and risky land acquisitions.

On March 7, 1791, Morris obtained title to a lot from

In 1787, Morris was sued in Virginia by Carter Braxton for £28,257; the lawsuit continued for eight years before commissioners were appointed, then Morris appealed. Finally Virginia's Court of Appeals led by Edmund Pendleton decided mostly in favor of Braxton before Morris was forced into bankruptcy by his own continued land speculations (although Morris as late as 1800 believed he should have won £20,000). Morris became increasingly fixated on land speculation, reaching his first major real estate deal in 1790 when he acquired much of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase in western New York. He realized a substantial profit the following year when he sold the land to The Pulteney Association, a group of British land speculators led by Sir William Pulteney, 5th Baronet, Sir William Johnstone Pulteney. Morris used the money from this sale to purchase the remainder of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase, then turned around and sold much of that land to the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch land speculators. These early successes encouraged Morris to pursue greater profits through increasingly large and risky land acquisitions.

On March 7, 1791, Morris obtained title to a lot from

/ref> on March 9, 1793, the site was surveyed; it wasn't until 1794 he began construction of a mansion on Chestnut Street (Philadelphia), Chestnut Street in Philadelphia designed by architect of Washington, D.C., Pierre Charles L'Enfant; it was to occupy an entire block between Chestnut Street and Walnut Street (Philadelphia), Walnut Street on the western edge of Philadelphia. The structure was of red brick and marble lining. Besides Land Speculation, Morris founded several canal companies: [Similar to the Potomac Company], two Pennsylvania canal companies were set up to try to link the produce of the western lands with the eastern markets; they were the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company chartered September 29, 1791, and the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company#Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company, Delaware and Schuylkill Canal Company chartered April 10, 1792. Morris was president of both companies; Development of Transportation Systems in the United States: Comprising a ... p. 44

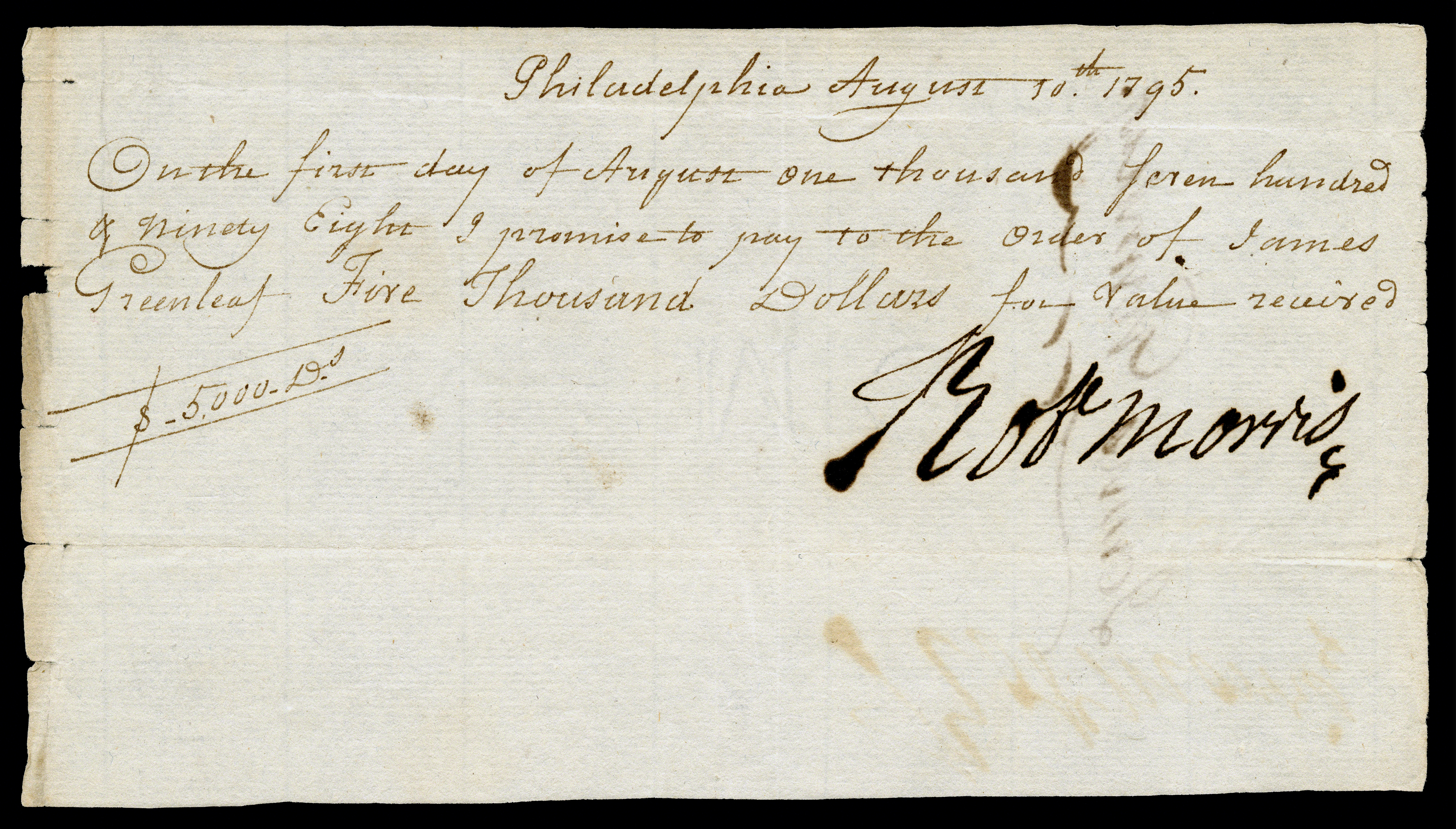

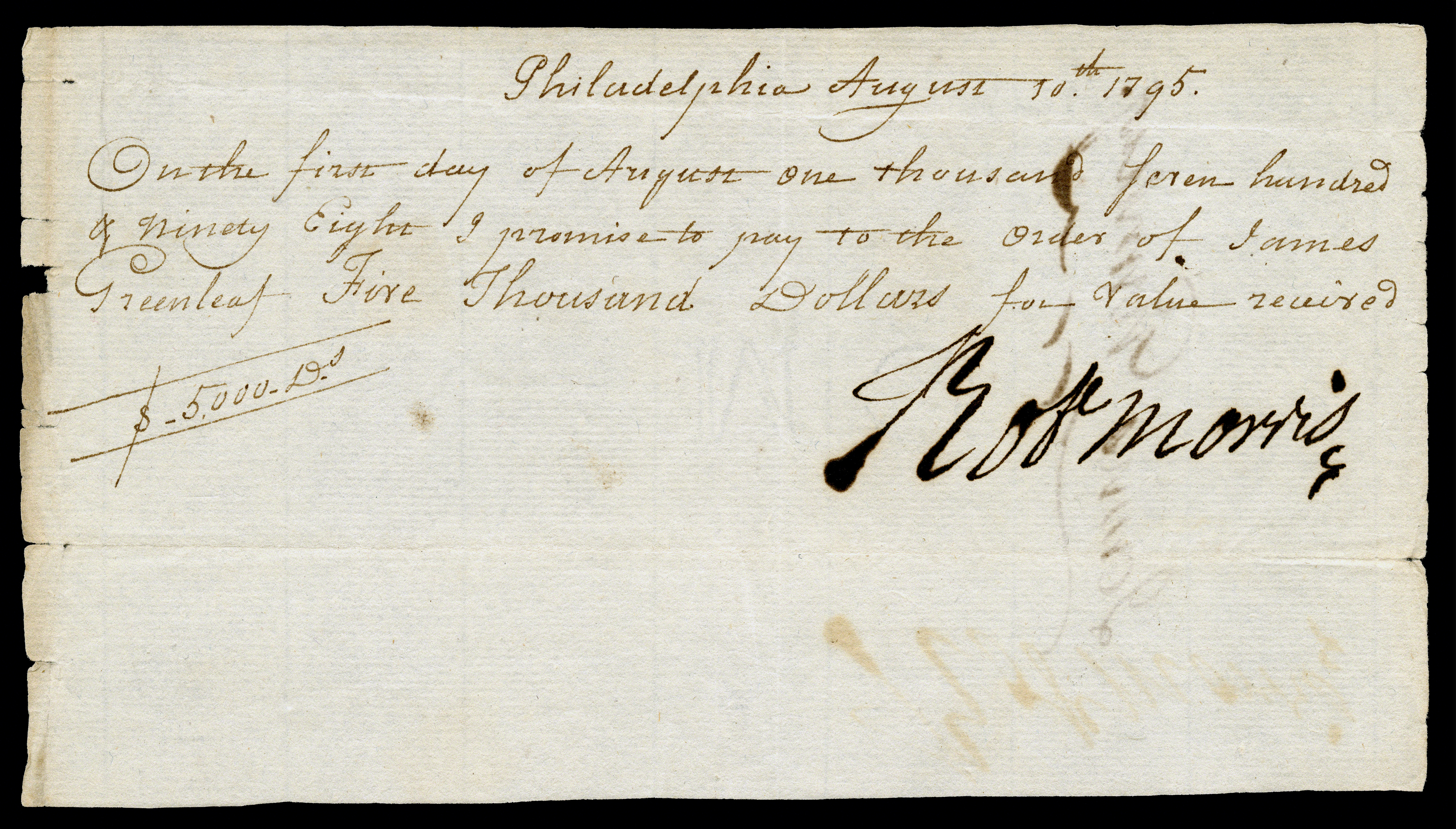

/ref> he was also involved with a steam engine company, and launched a hot air balloon from his garden on Market Street. He had the first iron rolling mill in America. His icehouse was the model for one Washington installed at Mount Vernon. He backed the new Chestnut Street Theater, and had a greenhouse where his staff cultivated lemon trees. In early 1793, Morris purchased shares in a land company led by John Nicholson, the comptroller general of Pennsylvania, beginning a deep business partnership between Nicholson and Morris. Later in 1793, Morris, Nicholson, and James Greenleaf jointly purchased thousands of lots in the recently established Washington, D.C., District of Columbia. They subsequently purchased millions of acres in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas; in each case, they went into debt to make the purchases, with the intent of quickly reselling the land to realize a profit. Morris and his partners struggled to re-sell their lands, and Greenleaf dropped out from the partnership in 1795. Morris realized a profit by selling his lots in the District of Columbia in 1796, but he and Nicholson still owed their creditors approximately $12 million (about $ in ). By Morris's own admission the beginning of his bankruptcy began with the failure of John Warder & Co. of Dublin and Donald and Burton of London in the spring of 1793. Morris was deeply involved in land speculation, especially after the Revolutionary War; (See Phelps and Gorham Purchase of 1791 above); on April 22, 1794, Morris entered into an association called the Asylum Company with John Nicholson, [who had served as Comptroller-General of the state of Pennsylvania from 1782 to 1794] to purchase 1,000,000 acres of Pennsylvania land besides land they already had title to in Luzerne County; Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, Northumberland County and Northampton County, Pennsylvania, Northampton County. [This was not the first partnership Morris and Nicholson were involved in; in 1792, Nicholson had negotiated the purchase from the federal government of the tract known as the Erie Triangle. Along with an agent of the Holland Land Company, Aaron Burr, Robert Morris, and other individual and institutional investors, he formed the Pennsylvania Population Company. This front organization purchased all 390 parcels of land in the Erie Triangle. Nicholson was Impeachment, impeached in 1794 for his role in the company.] However, Morris severely overextended himself financially. He had borrowed to speculate in real estate in the new national capital, Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, but signed a contract with a syndicate of Philadelphia investors to take over his obligations there. After that, he took the options to purchase over in the rural south. Unfortunately for Morris, that syndicate reneged on their commitment, leaving him once again liable, but this time with more exposure.Barbara Ann Chernow, ''Robert Morris, Land Speculator, 1790–1801'' (1978) In 1795, Morris and two of his partners, Greenleaf and Nicholson, pooled their land and formed a land company called the North American Land Company. The purpose of this company was to raise money by selling stock secured by the real estate [i.e. to finance their land speculation business]. According to one historian of American land speculation, the NALC was "largest land trust ever known in America". The three partners turned over to the company land throughout the United States totaling more than , most of it valued at about 50 cents an acre."Livermore165" In addition to land in the District of Columbia, there were in Georgia, in Kentucky, in North Carolina, in Pennsylvania, in South Carolina, and in Virginia. NALC was authorized to issue 30,000 shares, each worth $100. To encourage investors to purchase shares, the three partners guaranteed that a 6 percent dividend would be paid every year. To ensure that there was enough money to pay this divided, each partner agreed to put 3,000 of their own NALC shares in escrow."Roberts407" Greenleaf, Morris, and Nicholson were entitled to receive a 2.5 percent commission on any land the company sold. Greenleaf was named secretary of the new company. Other land speculations that Morris was involved in was the Illinois-Wabash Company and the Georgia Yazoo land scandal, Yazoo Land Company

and the land eventually became Jewelers' Row, Philadelphia, Sansom Street. Marble from this house was purchased by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Latrobe; he used it to adorn buildings and monuments from Rhode Island to Charleston, South Carolina, Charlestown, South Carolina. The two canal companies had also failed as well: for example after its incorporation the Schuylkill and Susquehanna was subscribed for 40,000 shares—but only 1000 shares were sold; the Delaware and Schuylkill company was to have been 2000 shares at $200.00 a share. Operations were suspended because "Either on account of errors in plans adopted, failure to procure the necessary means, financial convulsions, or a combination of all these difficulties, they were compelled to suspend their operations after an outlay of $440,000, which was an immense sum in those days". When England and the Dutch declared war on Revolutionary France, an expected loan from Holland never materialized. The subsequent Napoleonic Wars ruined the market for American land and Morris's highly leveraged company collapsed. Lastly, the financial markets of England, the United States, and the Caribbean suffered from deflation related with the Panic of 1796–97, Panic of 1797. Morris was left "land rich and cash poor". He ''owned'' more land than any other American at any time, but didn't have enough Hard money (policy), liquid capital to pay his creditors. Among his creditors was his son-in-law James Marshall for £20,000 sterling; likewise his brother-in-law Bishop White was also a creditor to Morris for $3,000. Gouvenor Morris was owned $24,000 "exclusive of what he paid in Europe on my account, the amount of which I do not know."; Henry Lee III was a creditor for protested bills for $39,446 plus damages and interest; Morris's wife Mary had a sum of credit of $15,860.16 from the sale of two farms left to her by her father;his daughter Esther Morris had a credit of a few hundred pounds left to her by her grandmother received by Morris; as Morris had given her on her marriage nothing but clothes and old wine he assigned to her two quarter chests of tea which he sent to Alexandria, Virginia for sale although he feared this would not amount to principal and interest; his son Robert Morris Jr was a debtor for sums spent in Europe without his father's knowledge; his son Charles while under age had contracted bills without his father's knowledge for $144.94 for a tailor and $24.50 for a shoemaker. The NALC encountered financial difficulty almost immediately. Only of land was turned over to the NALC, which meant it could issue only 22,365 shares. This meant only 7,455 shares were put into escrow (instead of the required 9,000). Rather than paying creditors with cash, the NALC paid them with shares (8,477 shares in 1795 and 1796). On May 15, 1795, the D.C. commissioners demanded their first payment from Greenleaf, Morris, and Nicholson, for the 6,000 lots purchased in 1793. But Greenleaf had misappropriated some of the company's income to pay his own debts. Without the Dutch mortgage income and missing funds, there was no money to make the payment to the commissioners. Furthermore, Greenleaf had co-signed for loans taken out by Morris and Nicholson. When these men defaulted, creditors sought out Greenleaf to make good on the debts—which he could not. Moris and his partners had failed to both pay the instalments on the Washington D.C. building lots and finished building twenty houses (they had contracted ten houses annually for seven years on said lots); On July 10, 1795, Morris and Nicholson bought out Greenleaf's interest in the December 24, 1793, agreement. The commissioners began legal proceedings to regain title to the 6,000 lots owned by NALC and the 1,115.25 lots owned by Greenleaf personally. The worsening financial problems of Greenleaf, Morris, and Nicholson led to increasingly poor personal relations among the three men."Sakolski165" Nicholson, particularly bitter, began making public accusations against Greenleaf in print. Morris attempted to mediate between the two men, but his efforts failed. In an attempt to resolve his financial problems, Greenleaf sold his shares in the NALC to Nicholson and Morris on May 28, 1796, for $1.5 million. Unfortunately, Morris and Nicholson funded their purchase by giving Greenleaf Security (finance), personal notes. Furthermore, they endorsed one another's notes. Morris and Nicholson, themselves nearly bankrupt, agreed to pay one-quarter of the purchase price every year for the next four years. Greenleaf's shares were not to be transferred to Morris and Nicholson until the fourth payment was received. On September 30, 1796, James Greenleaf put 7,455 of his NALC shares in a trust (known as the "391 trust" because it was recorded on page 391 of the firm's accounting book). The "391 trust" was created to generate income (from the 6 percent dividend) to pay a loan given to Greenleaf by Edward Fox. A trustee was assigned to hold on to the shares. The same day, Greenleaf put 2,545 shares into another trust (the "381 trust"), as a guarantee against nonpayment of the dividend by Morris and Nicholson.Livermore, p. 166. Morris and Nicholson's made the first payment to Greenleaf for the one-third interest in the NALC by turning over title to several hundred lots in Washington, D.C. On March 8, 1797, Greenleaf executed the 381 trust. When the NALC did not issue its 6 percent dividend, Greenleaf transferred one-third of the shares in the "391 trust" to the trustees. The total number of shares transferred to the "381 trust" trustees was now 6,119.Livermore, p. 169. On June 24, 1797, Morris, Greenleaf and Nicholson had conveyed their Washington D.C. Lots in trust to Henry Pratt and others in payments of their debts. Poor business practices were now dragging down NALC. For years, Morris and Nicholson had acted as personal guarantors for one another's notes. Now many of these notes were coming due, and neither man could pay them. Creditors began selling the notes publicly, often at heavy discounts."Mann201" By 1798, Morris and Nicholson's $10 million in personal notes were trading at one-eighth their face value. NALC also discovered that some of titles to the of land it owned were not clear, and thus the land could not be used for security. In other cases, NALC found it had been swindled, and the rich land it thought it owned turned out to be barren and worthless. Morris and Nicholson honestly believed that, if their cash flow problems were fixed, they could make payments on the property they owned and their shares would be returned to them. This proved incorrect. On October 23, 1807, all stock in the company was sold at 7 cents on the dollar to the accountants managing the Aggregate Fund. In 1856, the Trustees of the North American Land Company held $92,071.87. Morris and Nicholson's heirs sued to recover the stock and gain access to the income. The North American Land Company stayed in existence until 1872. An 1880 auditors report called the litigation "phenomenal ... the counsel for Morris and Nickerson pursued the fund for twenty-five years, seeking to obtain it from the trustees of the North American Company and the trusts which had been created from it, and also defending the money from the State in an attempt to sequestrate it. After all counsel fees and expenses, the amount available for division to the Morris interest was $9,692.49." In 1797 Morris conveyed his household furniture to Thomas Fitzsimmons which was sold at public auction. What was left was lent to Mrs. Morris by Fitzsimmons and Morris son-in-law Marshall; all Morris had left in his house was some bedding, clothing, part of a quarter cask of wine; part of a barrel of flour, some coffee, a little sugar and some bottled wine which was the remainder from a cask he had given to his daughter Maria. Morris attempted to avoid creditors by staying outside the city at his country estate "The Hills", located on the

Business, Government, and Congressional Investigation in the Revolution

', (1959), Via Jstor * Ferguson, E. James. ''The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance, 1776–1790'' (1961

online

* Herring, William Rodney. "The Rhetoric of Credit, the Rhetoric of Debt: Economic Arguments in Early America and Beyond." ''Rhetoric and Public Affairs'' 19.1 (2016): 45-82. * Kohn, Richard H. "The Inside History of the Newburgh Conspiracy: America and the Coup d'Etat." ''William and Mary Quarterly'' (1970) 27#2 pp: 188-220

online

* * * * Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. ''Robert Morris, Patriot and Financier'' (Macmillan, 1903

online

* Perkins, Edwin J. ''American public finance and financial services, 1700–1815'' (1994). pp. 85–105 on Revolution, pp. 106–36 on postwar

Complete text line free

* Rakove, Jack N. ''The beginnings of national politics: An interpretive history of the Continental Congress'' (Knopf, 1979) pp 297–330

online

* * Smith, Ryan K. ''Robert Morris's Folly: The Architectural and Financial Failures of an American Founder.'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014. * Ver Steeg, Clarence L. ''Robert Morris, Revolutionary Financier.'' Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1954

online

* Ver Steeg, Clarence L. "Morris, Robert" i

* *

Biography by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, 1856

The President's House

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Morris, Robert 1734 births 1806 deaths Politicians from Liverpool Businesspeople from Liverpool British emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies American people of English descent American Episcopalians Marshall family (political family), Marshall family Continental Congressmen from Pennsylvania Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Signers of the Articles of Confederation Signers of the United States Constitution Pro-Administration Party United States senators from Pennsylvania Members of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Politicians from Philadelphia American bankers American merchants American slave traders Central bankers Colonial American merchants Financiers of the American Revolution History of banking People imprisoned for debt Burials at Christ Church, Philadelphia Members of the American Philosophical Society United States senators who owned slaves

Founding Father of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary

Patriots, also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or American Whigs, were t ...

. He served as a member of the Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

legislature, the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

, and the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, and he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

, the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, and the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

. From 1781 to 1784, he served as the Superintendent of Finance of the United States, becoming known as the "Financier of the Revolution." Along with Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan– American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

, he is widely regarded as one of the founders of the financial system of the United States.

Born in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, Morris migrated to North America in his teens, quickly becoming a partner in a successful shipping firm based in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. In the aftermath of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, Morris joined with other merchants in opposing British tax policies such as the 1765 Stamp Act. By 1775 he was the richest man in America. After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, he helped procure arms and ammunition for the revolutionary cause, and in late 1775 he was chosen as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. As a member of Congress, he served on the Secret Committee of Trade, which handled the procurement of supplies, the Committee of Correspondence

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independe ...

, which handled foreign affairs, and the Marine Committee, which oversaw the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Adams ...

. Morris was a leading member of Congress until he resigned in 1778. Out of office, Morris refocused on his merchant career and won election to the Pennsylvania Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

, where he became a leader of the "Republican" faction that sought alterations to the Pennsylvania Constitution

The Constitution of Pennsylvania is the supreme law within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. All acts of the General Assembly, the governor, and each governmental agency are subordinate to it. Since 1776, Pennsylvania's Constitution has undergone ...

.

Facing a difficult financial situation in the ongoing Revolutionary War, in 1781 Congress established the position of Superintendent of Finance to oversee financial matters. Morris accepted appointment as Superintendent of Finance and also served as Agent of Marine, from which he controlled the Continental Navy. He helped provide supplies to the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

under General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, enabling, with the help of frequent collaborator Haym Salomon

Haym Salomon (also Solomon; anglicized from Chaim Salomon; April 7, 1740 – January 6, 1785) was a Polish-born Jewish businessman and political financial broker who assisted the Superintendent of Finance, English-born Robert Morris, as the prim ...

, Washington's decisive victory in the Battle of Yorktown. Morris also reformed government contracting and established the Bank of North America

The Bank of North America was the first chartered bank in the United States, and served as the country's first ''de facto'' central bank. Chartered by the Congress of the Confederation on May 26, 1781, and opened in Philadelphia on January 7, 17 ...

, the first congressionally chartered national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

to operate in the United States. Morris believed that the national government would be unable to achieve financial stability without the power to levy taxes and tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and polic ...

, but he was unable to convince all thirteen states to agree to an amendment to the Articles of Confederation.

Frustrated by the weakness of the national government, Morris resigned as Superintendent of Finance in 1784. Morris was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1786.

In 1787, Morris was selected as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

, which wrote and proposed a new constitution for the United States. Morris rarely spoke during the convention, but the constitution produced by the convention reflected many of his ideas. Morris and his allies helped ensure that Pennsylvania ratified the new constitution, and the document was ratified by the requisite number of states by the end of 1788. The Pennsylvania legislature subsequently elected Morris as one of its two inaugural representatives in the United States Senate. Morris declined Washington's offer to serve as the nation's first Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, instead suggesting Alexander Hamilton for the position. In the Senate, Morris supported Hamilton's economic program and aligned with the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

. During and after his service in the Senate, Morris went deeply into debt through speculating on land, leading into the Panic of 1796–1797

The Panic of 1796–1797 was a series of downturns in credit markets in both Great Britain and the newly established United States in 1796 that led to broader commercial downturns. In the United States, problems first emerged when a land speculati ...

. Unable to pay his creditors, he was confined in the Prune Street debtors' apartment adjacent to Walnut Street Prison

Walnut Street Prison was a city jail and prison, penitentiary house in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1790 to 1838. Legislation calling for establishment of the jail was passed in 1773 to relieve overcrowding in the High Street Jail; the first ...

from 1798 to 1801. After being released from prison, he lived a quiet, private life in a modest home in Philadelphia until his death in 1806.

Early life

Youth

Morris was born in youth, England, on January 20, 1734. His parents were Robert Morris Sr., anagent

Agent may refer to:

Espionage, investigation, and law

*, spies or intelligence officers

* Law of agency, laws involving a person authorized to act on behalf of another

** Agent of record, a person with a contractual agreement with an insuranc ...

for a shipping firm, and Elizabeth Murphet; biographer Charles Rappleye concludes that Morris was probably born out of wedlock

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

. Until he reached the age of thirteen, Morris was raised by his maternal grandmother in England. In 1747, Morris immigrated to Oxford, Maryland

Oxford is a waterfront town and former colonial port in Talbot County, Maryland, United States. The population was 651 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census.

History

Oxford is one of the oldest towns in Maryland. While Oxford officially ma ...

, where his father had prospered in the tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

trade. Two years later, Morris's father sent him to Philadelphia, then the most populous city in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

, where Morris lived under the care of his father's friend, Charles Greenway.

Merchant career

Greenway arranged for Morris to become an apprentice at the shipping and banking firm of Philadelphia merchant

Greenway arranged for Morris to become an apprentice at the shipping and banking firm of Philadelphia merchant Charles Willing

Charles Willing (May 18, 1710 – November 30, 1754) was a Philadelphia merchant, trader and politician; twice he served as Mayor of Philadelphia, from 1748 until 1749 and again in 1754.

Early life

Charles Willing was born in Bristol, Engla ...

. In 1750, Robert Morris Sr. died from an infected wound, leaving much of his substantial estate to his son. Morris impressed Willing and rose from a teenage trainee to become a key agent in Willing's firm. Morris traveled to Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

ports to expand the firm's business, and he gained a knowledge of trading and the various currencies used to exchange goods. He also befriended Thomas Willing

Thomas Willing (December 19, 1731 – January 19, 1821) was an American merchant, politician and slave trader who served as mayor of Philadelphia and was a delegate from Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress. He also served as the first pre ...

, the oldest son of Charles Willing who was two years older than Morris and who, like Morris, had split his life between England and British North America. Charles Willing died in 1754, and in 1757 Thomas made Morris a full partner in the newly renamed firm of Willing Morris & Company.

Morris's shipping firm was just one of many such firms operating in Philadelphia, but Willing Morris & Company pursued several innovative strategies. The firm pooled with other shipping firms to insure

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

vessels, aggressively expanded trade with India, and underwrote government projects through bonds and promissory notes. Ships of the firm traded with India, the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, Spanish Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Spain, and Italy. The firm's business of import, export, and general agency made it one of the most prosperous in Pennsylvania. In 1784, Morris, with other investors, underwrote the voyage of the ship '' Empress of China'', the first American vessel to visit the Chinese mainland.

Slavery

Morris's partnership with Willing was forged just after the beginning of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, which hindered attracting the usual supply of new indentured servants to the colony. Potential immigrants were conscripted in England to fight in Europe, and the contracts for those already in the colonies in America were expiring. At the same time, the British Crown wanted to encourage the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

which was profitable for the king's political allies in the African Company of Merchants

The African Company of Merchants or Company of Merchants Trading to Africa was a British chartered company operating from 1752 to 1821 in the Gold Coast area of modern Ghana, engaged in the Atlantic slave trade.

Background

The company was estab ...

. While Morris was a junior partner and Willing was pursuing a political career, the company Willing, Morris & Co. co-signed a petition calling for the repeal of Pennsylvania's tariff on imported slaves. (About 200 slaves were imported into Philadelphia in 1762, the height of the trade; most were brought in by the Rhode Islanders D'Wolf, Aaron Lopez

Aaron Lopez (1731–1782), born Duarte Lopez, was a merchant, slave trader, and philanthropist in colonial Rhode Island. Through his varied commercial ventures, he became the wealthiest person in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1761 and 1762, Lopez ...

, and Jacob Rivera.)

Willing, Morris & Co funded its own slave-trading voyage. The ship did not carry enough to be profitable and, during a second trip, was captured by French privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s. The firm handled two slave auctions for other importers, offering a total of 23 slaves. In 1762, the firm advertised an agency sale in Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

, for over 100 Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

slaves. The ship had docked in Wilmington to avoid the tariff. In 1765, on their last reported agency deal related to slavery (out of a total of eight), the firm advertised 17 slaves who were brought in from Africa on the ship ''Marquis de Granby''. The slaves were not sold in Philadelphia, as the owner took the ship and all the slaves to Jamaica. He worked on the slave trade and owned slaves until 1797.

Personal and family life

In early 1769, at age 35, Morris married 20-year-old Mary White, the daughter of a wealthy and prestigious lawyer and landholder. Mary gave birth to the couple's first of seven children in December 1769. (A son of Robert and Mary Morris was CongressmanThomas Morris (New York politician)

Thomas Morris (February 26, 1771 – March 12, 1849) was a United States representative from New York and was a son of Founding Father Robert Morris.

Early life

Morris was born on February 26, 1771 in Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylv ...

whose wife was related to the Livingston

Livingston may refer to:

Businesses

* Livingston Energy Flight, an Italian airline (2003–2010)

* Livingston Compagnia Aerea, an Italian airline (2011–2014), also known as Livingston Airline

* Livingston International, a North American custom ...

and Van Rensselaer New York political families). Morris and his family lived on Front Street in Philadelphia and maintained a second home, known as "The Hills," on the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It fl ...

to the northwest of the city. He later purchased another rural manor, which he named Morrisville, that was located across the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

from Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

Christ Church, which was also attended by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, Thomas Willing, and other leading citizens of Philadelphia. The Morris household employed several domestic workers and retained several slaves.

In addition to the children he sired with Mary White, Morris fathered a daughter, Polly, who was born out of wedlock around 1763. Morris supported Polly financially and remained in contact with her throughout her adult life. Morris also supported a younger half-brother, Thomas, whom Morris's father had sired out of wedlock shortly before his own death. Thomas eventually became a partner in Morris's shipping firm. Mary's brother, William White, was ordained as an Episcopal priest and served as the Senate chaplain.

In 1781, Morris purchased a home on

In 1781, Morris purchased a home on Market Street Market Street may refer to:

*Market Street, Cambridge, England

*Market Street, Fremantle, Western Australia, Australia

* Market Street, George Town, Penang, Malaysia

*Market Street, Manchester, England

*Market Street, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

...

that was two blocks north of Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Fa ...

, the seat of the Second Continental Congress. He gained clear title to the estate in 1785 and made it his primary residence. In 1790, President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

accepted Morris's offer to make the house his primary residence; Morris and his family subsequently moved to a smaller, neighboring property. By the 1790s, Morris had become close friends with Washington, and he and his wife were regular fixtures at state events thrown by the president. The President's House, as it became known, served as the residence of the president until 1800, when President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

moved to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

American Revolution

Rising tensions with Britain

In 1765, theParliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

imposed the Stamp Act, a tax on transactions involving paper that proved widely unpopular in British North America. In one of his first major political acts, Morris joined with several other merchants in pressuring British agent John Hughes to refrain from collecting the new tax. Facing colonial resistance, Parliament repealed the tax, but it later implemented other policies designed to generate tax revenue from the colonies. During the decade after the imposition of the Stamp Act, Morris would frequently join with other merchants in protesting many of Parliament's taxation policies. Writing to a friend about his objections to British tax policies, Morris stated that "I am a native of England but from principle am American in this dispute."Rappleye (2010), pp. 27–28 While his partner, Thomas Willing, served in various governmental positions, Morris declined to serve in any public office other than that of port warden (a position he shared with six other individuals), and he generally let Willing act as the public face of the firm.

In early 1774, in response to the Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

, many colonists in British North America began calling for a boycott of British goods. In Philadelphia, Willing, Charles Thomson

Charles Thomson (November 29, 1729 – August 16, 1824) was an Irish-born Patriot leader in Philadelphia during the American Revolution and the secretary of the Continental Congress (1774–1789) throughout its existence. As secretary, Thomson ...

, and John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

took the lead in calling for a congress of all the colonies to coordinate a response to British tax policies. Morris was not elected to the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

, which convened in Philadelphia in August 1774, but he frequently met with the congressional delegates and befriended colonial leaders such as George Washington and John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

. Morris generally sympathized with the position of the delegates who favored the reform of British policies but were unwilling to fully break with Britain. In September 1774, the First Continental Congress voted to create the Continental Association

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress on October 20, 1774. It called for a trade boycott against ...

, an agreement to enforce a boycott against British goods beginning in December; it also advised each colony to establish committees to enforce the boycott. Morris was elected to the Philadelphia committee charged with enforcing the boycott.

Continental Congress

Early war, 1775–August 1776

In April 1775, theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

broke out following the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

. Shortly thereafter, the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

began meeting in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, and Congress appointed George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

to command the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

established the twenty-five member Committee of Safety to supervise defenses, and Morris was appointed to the committee. Morris became part of the core group of members that directed the committee, and served as the committee's chairman when Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

was absent. Charged with obtaining gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

, Morris arranged a large-scale smuggling operation to avoid British laws designed to prevent arms and ammunition from being imported into the colonies. Due to his success at smuggling gunpowder for Pennsylvania, Morris also became the chief supplier of gunpowder to the Continental Army. Morris became increasingly focused on political affairs rather than business, and in October 1775 he won election to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. Later in the year, the Provincial Assembly elected Morris as a delegate to Congress.

In Congress, Morris aligned with the less radical faction of delegates that protested British policies but continued to favor reconciliation with Britain. He was appointed to the Secret Committee of Trade, which supervised the procurement of arms and ammunition. As the revolutionary government lacked an executive branch or a civil service, the committees of Congress handled all government business. Biographer Charles Rappleye writes that the committee "handled its contracts in a clubby, often incestuous manner" that may have unfairly benefited politically connected merchants, including Morris. However, Rappleye also notes that the dangerous and secretive nature of a committee charged with obtaining contraband goods made it difficult for the committee to establish competitive bidding

Bidding is an offer (often competitive) to set a price tag by an individual or business for a product or service ''or'' a demand that something be done. Bidding is used to determine the cost or value of something.

Bidding can be performed ...

procedures for procurement contracts. In addition to his service on the Secret Committee of Trade, Morris was also appointed to the Marine Committee, which oversaw the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Adams ...

, and the Committee of Secret Correspondence

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was a committee formed by the Second Continental Congress and active from 1775 to 1776. The Committee played a large role in attracting French aid and alliance during the American Revolution. In 1777, the C ...

, which oversaw efforts to establish relations with foreign powers. From his position on the latter committee, Morris helped arrange for the appointment of Silas Deane

Silas Deane (September 23, 1789) was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the ...

as Congress's representative to France; Deane was charged with procuring supplies and securing a formal alliance with France.

Throughout 1776, Morris would emerge as a key figure on the Marine Committee; Rappleye describes him as the "de facto commander" of the Continental Navy. Morris favored a naval strategy of attacking Britain's "defenseless places" in an effort to divide Britain's numerically superior fleet. Along with Franklin, Dickinson, and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Morris helped draft the Model Treaty

The Model Treaty, or the Plan of 1776, was a template for commercial treaties that the United States planned to make with foreign powers during the American Revolution against Great Britain. It was drafted by the Continental Congress to secure ec ...

, which was designed to serve as a template for relations with foreign countries. Unlike Britain's mercantile trade policies, the Model Treaty emphasized the importance of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

. In March 1776, after the death of Samuel Ward, Morris was named as the chairman of the Secret Committee of Trade. He established a network of agents, based in both the colonies and various foreign ports, charged with procuring supplies for the Continental war effort.

In late February 1776, Americans learned that the British Parliament had passed the Prohibitory Act, which declared that all American shipping was subject to seizure by British ships. Unlike many other congressional leaders, Morris continued to hope for reconciliation with Britain, since he believed that all-out war still lacked the strong support of a majority of Americans and would prove financially ruinous. In June 1776, due largely to frustration with the moderate faction of Pennsylvania leaders that included Morris, a convention of delegates from across Pennsylvania began meeting to draft a new constitution and establish a new state government. At the same time, Congress was debating whether to formally declare independence from Britain. By early July 1776, Pennsylvania's delegation was the lone congressional delegation opposed to declaring independence. Morris refused to vote for independence, but he and another Pennsylvania delegate agreed to excuse themselves from the vote on independence, thereby giving the pro-independence movement a majority in the Pennsylvania delegation. With Morris absent, all congressional delegations voted to pass a resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual mak ...

declaring independence on July 2, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

formally declared independence on July 4, 1776.

Despite his opposition to independence, and much to Morris's surprise, the Pennsylvania constitutional convention voted to keep Morris in Congress; he was the lone anti-independence delegate from Pennsylvania to retain his position. In August, Morris signed the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

despite having abstained. In explaining his decision, he stated, "I am not one of those politicians that run testy when my own plans are not adopted. I think it is the duty of a good citizen to follow when he cannot lead." He also stated, "while I do not wish to see my countrymen die on the field of battle nor do I wish to see them live in tyranny".

Continued war, August 1776–1778

After the Declaration of Independence was issued, Morris continued to supervise and coordinate efforts to secure arms and ammunition and export American goods. His strategy focused on using ships from New England to export tobacco and other goods from the Southern states to Europe and the islands of the Caribbean, then using the capital obtained from those exports to purchase military supplies from Europe. British spies and warships often frustrated his plans, and many American ships were captured in the midst of trading operations. In response, Morris authorized American envoys in Europe to commissionprivateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

to attack British shipping, and he arranged for an agent, William Bingham

William Bingham (March 8, 1752February 7, 1804) was an American statesman from Philadelphia. He was a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress from 1786 to 1788 and served in the United States Senate from 1795 to 1801. Bingham was o ...

, to pay for repairs to American privateers on the French island of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

. Due to the lucrative nature of privateering, Morris also started outfitting his own privateers. Another agent of Morris's, his half-brother Thomas Morris, proved a disastrous choice for managing American privateers in Europe, as Thomas engaged in binge drinking and mismanaged funds. In October 1776, at the urging of Morris and Benjamin Franklin, Congress authorized the appointment of two envoys charged with seeking a formal treaty of alliance with France; ultimately, Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee were appointed as those envoys. Along with Silas Deane, Franklin would help to greatly expand arms shipments from France and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, but Lee proved to be completely incompetent in his efforts to gain support from Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

.

In early December 1776, Washington's army was forced to retreat across the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

and into Pennsylvania, and most members of Congress temporarily left Philadelphia. Morris was one of few delegates to remain in the city, and Congress appointed Morris and two other delegates to "execute Continental business" in its absence. Morris frequently corresponded with Washington, and he provided supplies that helped enable the Continental victory at the Battle of Trenton. After the Continental Army was defeated in the September 1777 Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the Ame ...

, Congress fled west from Philadelphia; Morris and his family went to live at the estate they had recently purchased in Manheim, Pennsylvania. Morris obtained a leave of absence in late 1777, but he spent much of his time defending himself against attacks regarding alleged mismanagement and financial improprieties levied by the pro-slavery allies of Henry Laurens

Henry Laurens (December 8, 1792) was an American Founding Father, merchant, slave trader, and rice planter from South Carolina who became a political leader during the Revolutionary War. A delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Laure ...

, the president of the Continental Congress

The president of the United States in Congress Assembled, known unofficially as the president of the Continental Congress and later as the president of the Congress of the Confederation, was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress, the ...

. Due to his leave of absence, Morris did not play a large role in drafting the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, which would be the first constitution of the United States, but he signed the document in March 1778. As some states objected to the Articles, it would not enter into force until 1781.Rappleye (2010), pp. 144–145