Robert Juet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English

/ref> but others date his birth to around 1570. Other historians assert even less certainty;

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the  On 4 August, the ship was at

On 4 August, the ship was at

After the mutiny, Hudson's shallop broke out oars and tried to keep pace with the ''Discovery'' for some time. Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the ''Discovery'', enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind. Hudson and the other seven aboard the shallop were never seen again. Despite subsequent searches, including those conducted by

After the mutiny, Hudson's shallop broke out oars and tried to keep pace with the ''Discovery'' for some time. Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the ''Discovery'', enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind. Hudson and the other seven aboard the shallop were never seen again. Despite subsequent searches, including those conducted by

sea explorer

This is a list of maritime explorers. The list includes explorers which had contributed, and continue to contribute to human knowledge of the planet's geography, weather, biodiversity, human cultures, the expansion of trade, or established communic ...

and navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and parts of the northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

.

In 1607 and 1608, Hudson made two attempts on behalf of English merchants to find a rumoured Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the shipping route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands of Canada is accordingly called the Northwest Passage (N ...

to Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

via a route above the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

. In 1609, he landed in North America on behalf of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

and explored the region around the modern New York metropolitan area

The New York metropolitan area, also commonly referred to as the Tri-State area, is the largest metropolitan area in the world by urban area, urban landmass, at , and one of the list of most populous metropolitan areas, most populous urban agg ...

. Looking for a Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

to Asia on his ship '' Halve Maen'' ("Half Moon"), he sailed up the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

, which was later named after him, and thereby laid the foundation for Dutch colonization of the region.

On his final expedition, while still searching for the Northwest Passage, Hudson became the first European to see Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

and the immense Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

. In 1611, after wintering on the shore of James Bay

James Bay (french: Baie James; cr, ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, Wînipekw, dirty water) is a large body of water located on the southern end of Hudson Bay in Canada. Both bodies of water extend from the Arctic Ocean, of which James Bay is the southernmost par ...

, Hudson wanted to press on to the west, but most of his crew mutinied. The mutineers cast Hudson, his son, and seven others adrift; the Hudsons and their companions were never seen again.

Early life

Details of Hudson's birth and early life are mostly unknown. Some sources have identified him as having been born in about 1565,Henry Hudson's entry in ''Encyclopædia Britannica''/ref> but others date his birth to around 1570. Other historians assert even less certainty;

Peter C. Mancall

Peter Mancall (born June 18, 1959) is a professor of history at the University of Southern California whose work has focused on early America, American Indians, and the early modern Atlantic world.

Biography

A 1981 graduate of Oberlin Colleg ...

, for instance, states that " udsonwas probably born in the 1560s," while Piers Pennington gives no date at all. Hudson is thought to have spent many years at sea, beginning as a cabin boy

''Cabin Boy'' is a 1994 American fantasy comedy film, directed by Adam Resnick and co-produced by Tim Burton, which starred comedian Chris Elliott. Elliott co-wrote the film with Resnick. Both Elliott and Resnick worked for '' Late Night with Dav ...

and gradually working his way up to ship's captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

.

Exploration

Expedition to Arctic

One of Hudson's first forays into navigation and his first significant voyage was with John Davis in 1587, in search of a northwest passage. They sailed to the Arctic but were impeded by heavily ice packed waters and strong weather conditions.Expeditions of 1607 and 1608

In 1607, theMuscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company russian: Московская компания, Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint ...

of England hired Hudson to find a northerly route to the Pacific coast of Asia. At the time, the English were engaged in an economic battle with the Dutch for control of northwest routes. It was thought that, because the sun shone for three months in the northern latitudes in the summer, the ice would melt and a ship could make it across the "top of the world".

On 1 May 1607, Hudson sailed with a crew of ten men and a boy on the 80-ton ''Hopewell''. They reached the east coast of Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

on 14 June, coasting it northward until 22 June. Here the party named a headland "Young's Cape", a "very high mount, like a round castle" near it "Mount of God's Mercy" and land at 73° north latitude " Hold with Hope". After turning east, they sighted "Newland"—i.e. Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

—on 27 May, near the mouth of the great bay Hudson later simply named the "Great Indraught" ( Isfjorden).

On 13 July, Hudson and his crew estimated that they had sailed as far north as 80° 23′ N, but more likely only reached 79° 23′ N. The following day they entered what Hudson later in the voyage named "Whales Bay" (Krossfjorden

Krossfjorden (English: Cross Fjord) is a 30 km long fjord on the west coast of Spitsbergen, which is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in Norway. To the north, the fjord branches into Lillehöö ...

and Kongsfjorden

Kongsfjorden as seen from Blomstrandhalvøya

Kongsfjorden (Kongs Fjord or Kings Bay) is an inlet on the west coast of Spitsbergen, an island which is part of the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The inlet is long and ranges in width fr ...

), naming its northwestern point "Collins Cape" (Kapp Mitra) after his boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervi ...

, William Collins. They sailed north the following two days. On 16 July, they reached as far north as Hakluyt's Headland (which Thomas Edge

Thomas Edge (1587/88 – 29 December 1624) was an English merchant, whaler, and sealer who worked for the Muscovy Company in the first quarter of the 17th century. The son of Ellis Edge, Thomas Edge was born in the parish of Blackburn in Lancash ...

says Hudson named on this voyage) at 79° 49′ N, thinking they saw the land continue to 82° N (Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

's northernmost point is 80° 49′ N) when really it trended to the east. Encountering ice packed along the north coast, they were forced to turn back south. Hudson wanted to make his return "by the north of Greenland to Davis his Streights ( Davis Strait), and so for Kingdom of England", but ice conditions would have made this impossible. The expedition returned to Tilbury Hope on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

on 15 September.

Hudson reported large numbers of whales in Spitsbergen waters during this voyage. Many authors credit his reports as the catalyst for several nations sending whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

expeditions to the islands. This claim is contentious—others have pointed to strong evidence that it was Jonas Poole

Jonas Poole (bap. 1566 – 1612)Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). was an early 17th-century English explorer and sealer, and was significant in the history of whaling.

Voyages to Bear Island, 1604-1609

He served aboard vesse ...

's reports in 1610, that led to the establishment of English whaling, and voyages of Nicholas Woodcock

Nicholas Woodcock (c. 1585 - after June 1658?) was a 17th-century English mariner who sailed to Spitsbergen, Virginia, and Asia. He piloted the first Spanish whaling ship to Spitsbergen in 1612 and participated in the Anglo-Persian sieges of Kis ...

and Willem Cornelisz van Muyden in 1612, which led to the establishment of Dutch, French and Spanish whaling. The whaling industry itself was built by neither Hudson nor Poole—both were dead by 1612.

In 1608, English merchants of the East India

East India is a region of India consisting of the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha

and West Bengal and also the union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The region roughly corresponds to the historical region of Magadh ...

and Muscovy Companies again sent Hudson in the ''Hopewell'' to attempt to locate a passage to the Indies, this time to the east around northern Russia. Leaving London on 22 April, the ship travelled almost , making it to Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

well above the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

in July, but even in the summer they found the ice impenetrable and turned back, arriving at Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Ro ...

on 26 August.

Alleged discovery of Jan Mayen

According toThomas Edge

Thomas Edge (1587/88 – 29 December 1624) was an English merchant, whaler, and sealer who worked for the Muscovy Company in the first quarter of the 17th century. The son of Ellis Edge, Thomas Edge was born in the parish of Blackburn in Lancash ...

, "William Hudson" in 1608 discovered an island he named "Hudson's Tutches" (Touches) at 71° N, the latitude of Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger nort ...

. However, records of Hudson's voyages suggest that he could only have come across Jan Mayen in 1607 by making an illogical detour, and historians have pointed out that Hudson himself made no mention of it in his journal. There is also no cartographical proof of this supposed discovery.

Jonas Poole

Jonas Poole (bap. 1566 – 1612)Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). was an early 17th-century English explorer and sealer, and was significant in the history of whaling.

Voyages to Bear Island, 1604-1609

He served aboard vesse ...

in 1611 and Robert Fotherby

Robert Fotherby (died 1646) was an early 17th-century English explorer and whaler. From 1613 to 1615 he worked for the Muscovy Company, and from 1615 until his death for the East India Company.

Family ties

There was a family of Fotherbys in Gri ...

in 1615 both had possession of Hudson's journal while searching for his elusive Hold-with-Hope—which is now believed to have been on the east coast of Greenland—but neither had any knowledge of any discovery of Jan Mayen, an achievement which was only later attributed to Hudson. Fotherby eventually stumbled across Jan Mayen, thinking it a new discovery and naming it "Sir Thomas Smith's Island", though the first verifiable records of the discovery of the island had been made a year earlier, in 1614.

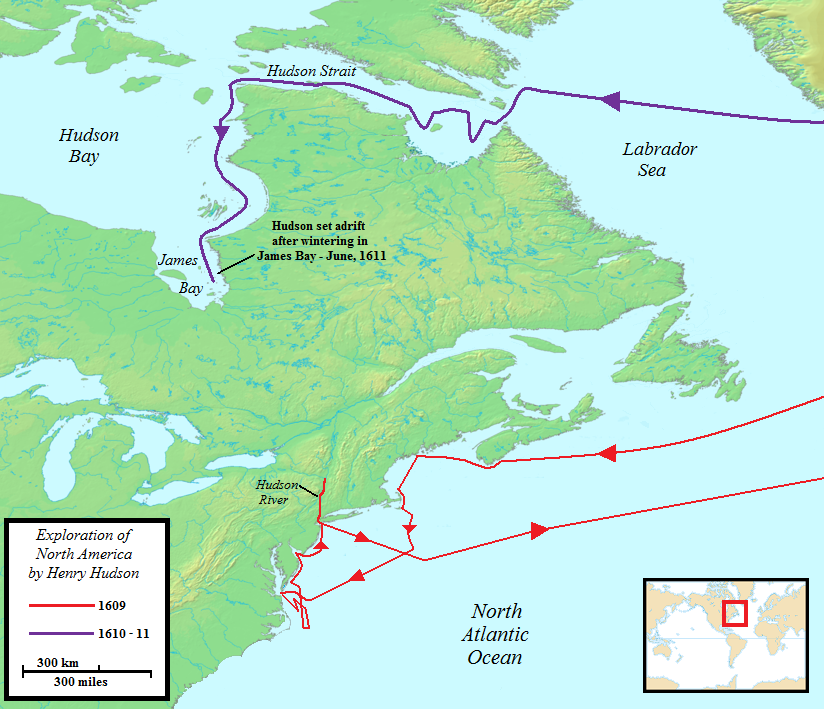

Expedition of 1609

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

in the Netherlands to find an easterly passage to Asia. While awaiting orders and supplies in Amsterdam, he heard rumours of a northwest route to the Pacific through North America. Hudson had been told to sail through the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

north of Russia, into the Pacific and so to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. Hudson departed Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

on 4 April, in command of the Dutch ship (English: Half Moon). He could not complete the specified (eastward) route because ice blocked the passage, as with all previous such voyages, and he turned the ship around in mid-May while somewhere east of Norway's North Cape. At that point, acting outside his instructions, Hudson pointed the ship west and decided to try to seek a westerly passage through North America.

They reached the Grand Banks of Newfoundland

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordf ...

on 2 July, and in mid-July made landfall near the LaHave area of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. Here they encountered First Nations who were accustomed to trading with the French; they were willing to trade beaver pelts, but apparently no trades occurred. The ship stayed in the area about ten days, the crew replacing a broken mast and fishing for food. On the 25 July, a dozen men from the ''Halve Maen'', using muskets and small cannon, went ashore and assaulted the village near their anchorage. They drove the people from the settlement and took their boat and other property—probably pelts and trade goods.

On 4 August, the ship was at

On 4 August, the ship was at Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

, from which Hudson sailed south to the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. Rather than entering the Chesapeake he explored the coast to the north, finding Delaware Bay but continuing on north. On 3 September, he reached the estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

of the river that initially was called the "North River" or "Mauritius" and now carries his name. He was not the first European to discover the estuary, though, as it had been known since the voyage of Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic ...

in 1524.

On 6 September 1609, John Colman

John Colman (died September 6, 1609) was a crew member of the '' Half Moon'' under Henry Hudson who was killed by Native Americans by an arrow to his neck.

Biography

On September 6, 1609, only five days after the arrival of the first Dutch and En ...

of his crew was killed by natives with an arrow to his neck. Hudson sailed into the Upper New York Bay on 11 September, and the following day encountered a group of 28 Lenape canoes, buying oysters and beans from the Native Americans, and then began a journey up what is now known as the Hudson River. Over the next ten days his ship ascended the river, reaching a point near Kinderhook, and the ship's boat with five crew members ventured to the vicinity of present-day Albany.

On 23 September, Hudson decided to return to Europe. He put in at Dartmouth Dartmouth may refer to:

Places

* Dartmouth, Devon, England

** Dartmouth Harbour

* Dartmouth, Massachusetts, United States

* Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada

* Dartmouth, Victoria, Australia

Institutions

* Dartmouth College, Ivy League university i ...

, England on 7 November, and was detained by authorities who wanted access to his log. He managed to pass the log to the Dutch ambassador to England, who sent it, along with his report, to Amsterdam.

While exploring the river, Hudson had traded with several native groups, mainly obtaining furs. His voyage was used to establish Dutch claims to the region and to the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

that prospered there when a trading post was established at Albany in 1614. New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

on Manhattan Island

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

became the capital of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

in 1625.

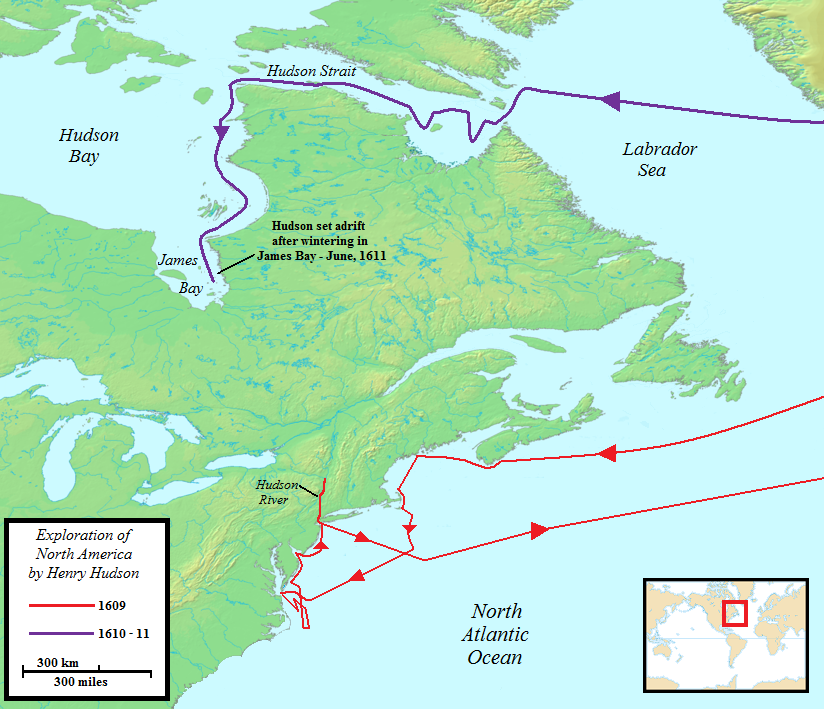

Expedition of 1610–1611

In 1610, Hudson obtained backing for another voyage, this time under the English flag. The funding came from the Virginia Company and the BritishEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

. At the helm of his new ship, the , he stayed to the north—some claim he deliberately stayed too far south on his Dutch-funded voyage—reached Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

on 11 May, the south of Greenland on 4 June, and rounded the southern tip of Greenland.

On 25 June, the explorers reached what is now the Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

at the northern tip of Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

. Following the southern coast of the strait on 2 August, the ship entered Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

. Excitement was very high due to the expectation that the ship had finally found the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

through the continent. Hudson spent the following months mapping and exploring its eastern shores, but he and his crew did not find a passage to Asia. In November, however, the ship became trapped in the ice in James Bay

James Bay (french: Baie James; cr, ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, Wînipekw, dirty water) is a large body of water located on the southern end of Hudson Bay in Canada. Both bodies of water extend from the Arctic Ocean, of which James Bay is the southernmost par ...

, and the crew moved ashore for the winter.

Mutiny

When the ice cleared in the spring of 1611, Hudson planned to use his ''Discovery'' to further explore Hudson Bay with the continuing goal of discovering the Passage; however, most of the members of his crew ardently desired to return home. Matters came to a head and much of the crew mutinied in June. Descriptions of the successful mutiny are one-sided, because the only survivors who could tell their story were the mutineers and those who went along with the mutiny. In the latter class was ship's navigator, Abacuk Pricket, a survivor who kept a journal that was to become one of the sources for the narrative of the mutiny. According to Pricket, the leaders of the mutiny were Henry Greene and Robert Juet. The latter, a navigator, had accompanied Hudson on the 1609 expedition, and his account is said to be "the best contemporary record of the voyage". Pricket's narrative tells how the mutineers set Hudson, his teenage son John, and seven crewmen—men who were either sick and infirm or loyal to Hudson—adrift from the ''Discovery'' in a smallshallop

Shallop is a name used for several types of boats and small ships (French ''chaloupe'') used for coastal navigation from the seventeenth century. Originally smaller boats based on the chalupa, the watercraft named this ranged from small boats a l ...

, an open boat, effectively marooning them in Hudson Bay. The Pricket journal reports that the mutineers provided the castaways with clothing, powder and shot, some pikes, an iron pot, some food, and other miscellaneous items.

Disappearance

After the mutiny, Hudson's shallop broke out oars and tried to keep pace with the ''Discovery'' for some time. Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the ''Discovery'', enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind. Hudson and the other seven aboard the shallop were never seen again. Despite subsequent searches, including those conducted by

After the mutiny, Hudson's shallop broke out oars and tried to keep pace with the ''Discovery'' for some time. Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the ''Discovery'', enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind. Hudson and the other seven aboard the shallop were never seen again. Despite subsequent searches, including those conducted by Thomas Button

Sir Thomas Button (died April, 1634) was a Wales, Welsh officer of the Royal Navy, notable as an explorer who in 1612–1613 commanded an expedition that unsuccessfully attempted to locate explorer Henry Hudson and to navigate the Northwest Pa ...

in 1612, and by Zachariah Gillam

Zachariah Gillam (also spelled Zachary Guillam) (1636–1682) was one of a family of New England sea captains involved in the early days of the Hudson's Bay Company.

Biography

The son of a prominent Massachusetts shipwright, he was engaged in th ...

in 1668–1670, their fate is unknown.

Pricket's reliability

Pricket's journal and testimony have been severely criticized for bias, on two grounds. Firstly, prior to the mutiny the alleged leaders of the uprising, Greene and Juet, had been friends and loyal seamen of Hudson. Secondly, Greene and Juet did not survive the return voyage to England (Juet, who had been the navigator on the return journey, died of starvation a few days before the company reached Ireland). Pricket knew he and the other survivors of the mutiny would be tried in England forpiracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

, and it would have been in his interest, and the interest of the other survivors, to put together a narrative that would place the blame for the mutiny upon men who were no longer alive to defend themselves.

The Pricket narrative became the controlling story of the expedition's disastrous end. Only eight of the thirteen mutinous crewmen survived the return voyage to Europe. They were arrested in England, and some were put on trial, but no punishment was imposed for the mutiny. One theory holds that the survivors were considered too valuable as sources of information to execute, as they had travelled to the New World and could describe sailing routes and conditions.

Legacy

The gulf or bay visited by Hudson is three times the size of theBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, and its many large estuaries afford access to otherwise landlocked parts of Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West or the Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a Canadian region that includes the four western provinces just north of the Canada� ...

and the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

. This allowed the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

to exploit a lucrative fur trade along its shores for more than two centuries, growing powerful enough to influence the history and present international boundaries of western North America. Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

became the entrance to the Arctic for all ships engaged in the historic search for the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

from the Atlantic side – though modern voyages take more northerly routes.

Along with Hudson Bay, many other topographical features and landmarks are named for Hudson. The Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

in New York and New Jersey is named after him, as are Hudson County, New Jersey

Hudson County is the most densely populated county in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It lies west of the lower Hudson River, which was named for Henry Hudson, the sea captain who explored the area in 1609. Part of New Jersey's Gateway Region in t ...

, the Henry Hudson Bridge

The Henry Hudson Bridge is a steel arch toll bridge in New York City across the Spuyten Duyvil Creek. It connects Spuyten Duyvil in the Bronx with Inwood in Manhattan to the south, via the Henry Hudson Parkway (NY 9A). On the Manhattan side, t ...

, the Henry Hudson Parkway

The Henry Hudson Parkway is a parkway in New York City. The southern terminus is in Manhattan at 72nd Street, where the parkway continues south as the West Side Highway. It is often erroneously referred to as the West Side Highway throughout it ...

, and the town of Hudson, New York

Hudson is a city and the county seat of Columbia County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 5,894. Located on the east side of the Hudson River and 120 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, it was named for the rive ...

. The unbuilt Hendrik Hudson Hotel in New York, planned circa 1897, was also to have been named after him. Instead, ten years later, an apartment building bearing the name had been constructed.

See also

*Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

* List of people who disappeared before 1970

* List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

Throughout history, people have mysteriously disappeared at sea, many on voyages aboard floating vessels or traveling via aircraft. The following is a list of known individuals who have mysteriously vanished in open waters, and whose whereabouts r ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * Juet, Robert (1609), ''Juet's Journal of Hudson's 1609 Voyage'' from the 1625 edition of Purchas His Pilgrimes and transcribed 2006 by Brea Barthel, . * * Purchas, S. 1625. Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and others. Volumes XIII and XIV (Reprint 1906 J. Maclehose and sons). * * Wordie, J.M. (1922). "Jan Mayen Island", ''The Geographical Journal''. Vol 59 (3).External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hudson, Henry 16th-century English people 17th-century English people 17th-century explorers 1560s births 1610s deaths 1610s missing person cases Dutch East India Company people English explorers of North America English navigators Sailors from London Explorers of Canada Explorers of Svalbard Explorers of the Arctic Explorers of the United States Lost explorers Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Sailors on ships of the Dutch East India Company Muscovy Company