Robert Hooke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English

Investigating in

In 1653, Hooke (who had also undertaken a course of twenty lessons on the organ) secured a chorister's place at Christ Church,

In 1653, Hooke (who had also undertaken a course of twenty lessons on the organ) secured a chorister's place at Christ Church,

Much has been written about the unpleasant side of Hooke's personality, starting with comments by his first biographer, Richard Waller, that Hooke was "in person, but despicable" and "melancholy, mistrustful, and jealous." Waller's comments influenced other writers for well over two centuries, so that a picture of Hooke as a disgruntled, selfish, anti-social curmudgeon dominates many older books and articles. For example, Arthur Berry said that Hooke "claimed credit for most of the scientific discoveries of the time." Sullivan wrote that Hooke was "positively unscrupulous" and possessing an "uneasy apprehensive vanity" in dealings with Newton. Manuel used the phrase "cantankerous, envious, vengeful" in his description. More described Hooke having both a "cynical temperament" and a "caustic tongue." Andrade was more sympathetic, but still used the adjectives "difficult", "suspicious", and "irritable" in describing Hooke.

The publication of Hooke's diary in 1935 revealed previously unknown details about his social and familial relationships. Biographer Margaret argued that "the picture which is usually painted of Hooke as a morose... recluse is completely false." Hooke interacted with noted craftsmen such as

Much has been written about the unpleasant side of Hooke's personality, starting with comments by his first biographer, Richard Waller, that Hooke was "in person, but despicable" and "melancholy, mistrustful, and jealous." Waller's comments influenced other writers for well over two centuries, so that a picture of Hooke as a disgruntled, selfish, anti-social curmudgeon dominates many older books and articles. For example, Arthur Berry said that Hooke "claimed credit for most of the scientific discoveries of the time." Sullivan wrote that Hooke was "positively unscrupulous" and possessing an "uneasy apprehensive vanity" in dealings with Newton. Manuel used the phrase "cantankerous, envious, vengeful" in his description. More described Hooke having both a "cynical temperament" and a "caustic tongue." Andrade was more sympathetic, but still used the adjectives "difficult", "suspicious", and "irritable" in describing Hooke.

The publication of Hooke's diary in 1935 revealed previously unknown details about his social and familial relationships. Biographer Margaret argued that "the picture which is usually painted of Hooke as a morose... recluse is completely false." Hooke interacted with noted craftsmen such as

Hooke first announced his law of elasticity as an anagram. This was a method sometimes used by scientists, such as Hooke, Huygens, Galileo, and others, to establish priority for a discovery without revealing details.

Hooke became Curator of Experiments in 1662 to the newly founded Royal Society, and took responsibility for experiments performed at its weekly meetings. This was a position he held for over 40 years. While this position kept him in the thick of science in Britain and beyond, it also led to some heated arguments with other scientists, such as Huygens (see above) and particularly with

Hooke first announced his law of elasticity as an anagram. This was a method sometimes used by scientists, such as Hooke, Huygens, Galileo, and others, to establish priority for a discovery without revealing details.

Hooke became Curator of Experiments in 1662 to the newly founded Royal Society, and took responsibility for experiments performed at its weekly meetings. This was a position he held for over 40 years. While this position kept him in the thick of science in Britain and beyond, it also led to some heated arguments with other scientists, such as Huygens (see above) and particularly with

,

online facsimile here

Hooke clearly postulated mutual attractions between the Sun and planets, in a way that increased with nearness to the attracting body. Hooke's statements up to 1674 made no mention, however, that an inverse square law applies or might apply to these attractions. Hooke's gravitation was also not yet universal, though it approached universality more closely than previous hypotheses. Hooke also did not provide accompanying evidence or mathematical demonstration. On these two aspects, Hooke stated in 1674: "Now what these several degrees f gravitational attractionare I have not yet experimentally verified" (indicating that he did not yet know what law the gravitation might follow); and as to his whole proposal: "This I only hint at present", "having my self many other things in hand which I would first compleat, and therefore cannot so well attend it" (i.e. "prosecuting this Inquiry"). In November 1679, Hooke initiated a remarkable exchange of letters with Newton (of which the full text is now published).Turnbull, H W (ed.) (1960), ''Correspondence of Isaac Newton'', Vol. 2 (1676–1687), Cambridge University Press, giving the Hooke-Newton correspondence (of November 1679 to January 1679/80) at pp. 297–314, and the 1686 correspondence over Hooke's priority claim at pp. 431–448. Hooke's ostensible purpose was to tell Newton that Hooke had been appointed to manage the Royal Society's correspondence. Hooke therefore wanted to hear from members about their researches, or their views about the researches of others; and as if to whet Newton's interest, he asked what Newton thought about various matters, giving a whole list, mentioning "compounding the celestial motions of the planetts of a direct motion by the tangent and an attractive motion towards the central body", and "my hypothesis of the lawes or causes of springinesse", and then a new hypothesis from Paris about planetary motions (which Hooke described at length), and then efforts to carry out or improve national surveys, the difference of latitude between London and Cambridge, and other items. Newton's reply offered "a fansy of my own" about a terrestrial experiment (not a proposal about celestial motions) which might detect the Earth's motion, by the use of a body first suspended in air and then dropped to let it fall. The main point was to indicate how Newton thought the falling body could experimentally reveal the Earth's motion by its direction of deviation from the vertical, but he went on hypothetically to consider how its motion could continue if the solid Earth had not been in the way (on a spiral path to the centre). Hooke disagreed with Newton's idea of how the body would continue to move. A short further correspondence developed, and towards the end of it Hooke, writing on 6 January 1679, 80 to Newton, communicated his "supposition ... that the Attraction always is in a duplicate proportion to the Distance from the Center Reciprocall, and Consequently that the Velocity will be in a subduplicate proportion to the Attraction and Consequently as Kepler Supposes Reciprocall to the Distance." (Hooke's inference about the velocity was actually incorrect) In 1686, when the first book of Newton's '' Principia'' was presented to the Royal Society, Hooke claimed that he had given Newton the "notion" of "the rule of the decrease of Gravity, being reciprocally as the squares of the distances from the Center". At the same time (according to

In 1655, according to his autobiographical notes, Hooke began to acquaint himself with astronomy, through the good offices of John Ward. Hooke applied himself to the improvement of the

In 1655, according to his autobiographical notes, Hooke began to acquaint himself with astronomy, through the good offices of John Ward. Hooke applied himself to the improvement of the

Hooke recorded that he conceived of a way to determine

Hooke recorded that he conceived of a way to determine

Hooke's 1665 book ''

Hooke's 1665 book ''

One of the observations in ''Micrographia'' was of

One of the observations in ''Micrographia'' was of

One of the more-challenging problems tackled by Hooke was the measurement of the distance to a star (other than the Sun). The star chosen was

One of the more-challenging problems tackled by Hooke was the measurement of the distance to a star (other than the Sun). The star chosen was

Hooke was Surveyor to the City of London and chief assistant to

Hooke was Surveyor to the City of London and chief assistant to

No authenticated portrait of Robert Hooke exists. This situation has sometimes been attributed to the heated conflicts between Hooke and Newton, although Hooke's biographer Allan Chapman rejects as a myth the claims that Newton or his acolytes deliberately destroyed Hooke's portrait. German antiquarian and scholar

No authenticated portrait of Robert Hooke exists. This situation has sometimes been attributed to the heated conflicts between Hooke and Newton, although Hooke's biographer Allan Chapman rejects as a myth the claims that Newton or his acolytes deliberately destroyed Hooke's portrait. German antiquarian and scholar

* 3514 Hooke, an asteroid (1971 UJ)

* Craters on the

* 3514 Hooke, an asteroid (1971 UJ)

* Craters on the

Lectures de potentia restitutiva, or, Of spring explaining the power of springing bodies

'. London : Printed for John Martyn. 1678. * * ''Micrographia'

full text at

with illustrations at Internet Archive

* includes ''An Attempt to prove the Annual Motion of the Earth, Animadversions on the Machina Coelestis of Mr. Hevelius, A Description of Helioscopes with other instruments, Mechanical Improvement of Lamps, Remarks about Comets 1677, Microscopium, Lectures on the Spring'', etc. * *

File:Hooke-1.jpg, 1678 copy of Hooke's "Lectures de potentia restitutiva"

File:Hooke-2.jpg, Title page of "Lectures de potentia restitutiva"

File:Hooke-3.jpg, First page of "Lectures de potentia restitutiva"

File:Hooke-4.jpg, Figure from "Lectures de potentia restitutiva"

File:Hooke-5.jpg, Figure from "Lectures de potentia restitutiva"

''Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses with observations and inquiries thereupon...''

* * (Published in the US as ''The Forgotten Genius'') *

Robert Hooke

hosted by Westminster School * * * * * ''Micrographia'' *

Hooke's ''Micrographia''

at

''Micrographia''

at

Digitzed images of ''Micrographia''

housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center

Lost manuscript of Robert Hooke discovered

nbsp;– from

Manuscript bought for The Royal Society

nbsp;– from

Robert Hooke's Books

a searchable database of books that belonged to or were annotated by Robert Hooke * * – A 60-minute presentation by Prof. Michael Cooper,

''The posthumous works of Robert Hooke''

(1705) – full digital facsimile from

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

active as a scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts Scientific method, scientific research to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, ...

, natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

and architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s in 1665 using a compound microscope that he built himself, the other scientist being Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

in 1676. An impoverished scientific inquirer in young adulthood, he found wealth and esteem by performing over half of the architectural surveys after London's great fire of 1666

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

. Hooke was also a member of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and since 1662 was its curator of experiments. Hooke was also Professor of Geometry at Gresham College.

As an assistant to physical scientist Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

, Hooke built the vacuum pumps used in Boyle's experiments on gas law, and himself conducted experiments. In 1673, Hooke built the earliest Gregorian telescope, and then he observed the rotations of the planets Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

and Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

. Hooke's 1665 book ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon.'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It ...

'', in which he coined the term "cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

", spurred microscopic investigations.;Investigating in

optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

, specifically light refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenome ...

, he inferred a wave theory of light

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies Interference (wave propagation), interference, diffraction, Polarization (waves), polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric opti ...

. And his is the first recorded hypothesis of heat expanding matter, air's composition by small particles at larger distances, and heat as energy.

In physics, he approximated experimental confirmation that gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

heeds an inverse square law, and first hypothesised such a relation in planetary motion, too, a principle furthered and formalised by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

in Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distan ...

. Priority over this insight contributed to the rivalry between Hooke and Newton, who thus antagonized Hooke's legacy. In geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, Hooke originated the theory of a terraqueous globe, disputed the literally Biblical view of the Earth's age, hypothesised the extinction of species, and argued that fossils atop hills and mountains had become elevated by geological processes. Thus observing microscopic fossils, Hooke presaged the theory of biological evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. Hooke's pioneering work in land surveying and in mapmaking

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

aided development of the first modern plan-form map, although his grid-system plan for London was rejected in favour of rebuilding along existing routes. Even so, Hooke was key in devising for London a set of planning controls that remain influential. In recent times, he has been called "England's Leonardo

Leonardo is a masculine given name, the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese equivalent of the English, German, and Dutch name, Leonard

Leonard or ''Leo'' is a common English masculine given name and a surname.

The given name and surname originate ...

".

Life and works

Early life

Much of what is known of Hooke's early life comes from an autobiography that he commenced in 1696 but never completed. Richard Waller mentions it in his introduction to ''The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke, M.D. S.R.S.'', printed in 1705. The work of Waller, along with John Ward's ''Lives of the Gresham Professors'' (with a list of his major works) andJohn Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

's ''Brief Lives'', form the major near-contemporaneous biographical accounts of Hooke.

Robert Hooke was born in 1635 in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

to Cecily Gyles and John Hooke, an Anglican priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

, the curate of Freshwater's Church of All Saints. Father John Hooke's two brothers, Robert's paternal uncles, were also ministers. A royalist, John Hooke likely was among a group that went to pay respects to Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

as he escaped to the Isle of Wight. Expected to join the church, Robert, too, would become a staunch monarchist. Robert was the youngest, by seven years, of four siblings, two boys and two girls. Their father led a local school as well, yet at least partly homeschooled Robert, frail in health. The young Robert Hooke was fascinated by observation, mechanical works, and drawing. He dismantled a brass clock and built a wooden replica that reportedly worked "well enough". He made his own drawing materials from coal, chalk, and ruddle (iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

).

On his father's death in 1648, Robert inherited 40 pounds. He took this to London with the aim of beginning an apprenticeship, and studied briefly with Samuel Cowper and Peter Lely

Sir Peter Lely (14 September 1618 – 7 December 1680) was a painter of Dutch origin whose career was nearly all spent in England, where he became the dominant portrait painter to the court.

Life

Lely was born Pieter van der Faes to Dutch ...

, but was persuaded instead to enter Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

by its headmaster Dr. Richard Busby

Richard Busby (; 22 September 1606 – 6 April 1695) was an English Anglican priest who served as head master of Westminster School for more than fifty-five years. Among the more illustrious of his pupils were Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Rob ...

. Hooke quickly mastered Latin and Greek, mastered Euclid's ''Elements'', learned to play the organ, and began his lifelong study of mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

.

Oxford

In 1653, Hooke (who had also undertaken a course of twenty lessons on the organ) secured a chorister's place at Christ Church,

In 1653, Hooke (who had also undertaken a course of twenty lessons on the organ) secured a chorister's place at Christ Church, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. He was employed as a "chemical assistant" to Dr Thomas Willis

Thomas Willis FRS (27 January 1621 – 11 November 1675) was an English doctor who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology and psychiatry, and was a founding member of the Royal Society.

Life

Willis was born on his pare ...

, for whom Hooke developed a great admiration. There he met the natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

, and gained employment as his assistant from about 1655 to 1662, constructing, operating, and demonstrating Boyle's "machina Boyleana" or air pump. In 1659, Hooke described some elements of a method of heavier-than-air flight to Wilkins, but concluded that human muscles were insufficient to the task. In 1662, he was awarded a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree.

Hooke himself characterised his Oxford days as the foundation of his lifelong passion for science, and the friends he made there were of paramount importance to him throughout his career, particularly Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

. Wadham was then under the guidance of John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the f ...

, who had a profound impact on Hooke and those around him. There was a sense of urgency in preserving the scientific work which they perceived as being threatened by The Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, refers to the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Co ...

. Wilkins' "philosophical meetings" in his study were clearly important, though few records survive except for the experiments Boyle conducted in 1658 and published in 1660. This group went on to form the nucleus of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. Hooke developed an air pump for Boyle's experiments based on the pump of Ralph Greatorex

Ralph Greatorex (c. 1625–1675)Sarah Bendall, 'Greatorex, Ralph (c.1625–1675)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 200retrieved 6 Feb 2011/ref> was a mathematical instrument maker. He was an ...

, which was considered, in Hooke's words, "too gross to perform any great matter." It is known that Hooke had a particularly keen eye, and was an adept mathematician, neither of which applied to Boyle. It has been suggested that Hooke probably made the observations and may well have developed the mathematics of Boyle's law

Boyle's law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law, or Mariotte's law (especially in France), is an experimental gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle's law has been stated as:

The ...

. Regardless, it is clear that Hooke was a valued assistant to Boyle and the two retained a mutual high regard.

A chance surviving copy of Willis's pioneering , a gift from the author, was chosen by Hooke from Wilkins' library on his death as a memento at John Tillotson

John Tillotson (October 1630 – 22 November 1694) was the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury from 1691 to 1694.

Curate and rector

Tillotson was the son of a Puritan clothier at Haughend, Sowerby, Yorkshire. Little is known of his early youth ...

's invitation. This book is now in the Wellcome Library

The Wellcome Library is founded on the collection formed by Sir Henry Wellcome (1853–1936), whose personal wealth allowed him to create one of the most ambitious collections of the 20th century. Henry Wellcome's interest was the history of me ...

. The book and its inscription in Hooke's hand are a testament to the lasting influence of Wilkins and his circle on the young Hooke.

Royal Society

TheRoyal Society

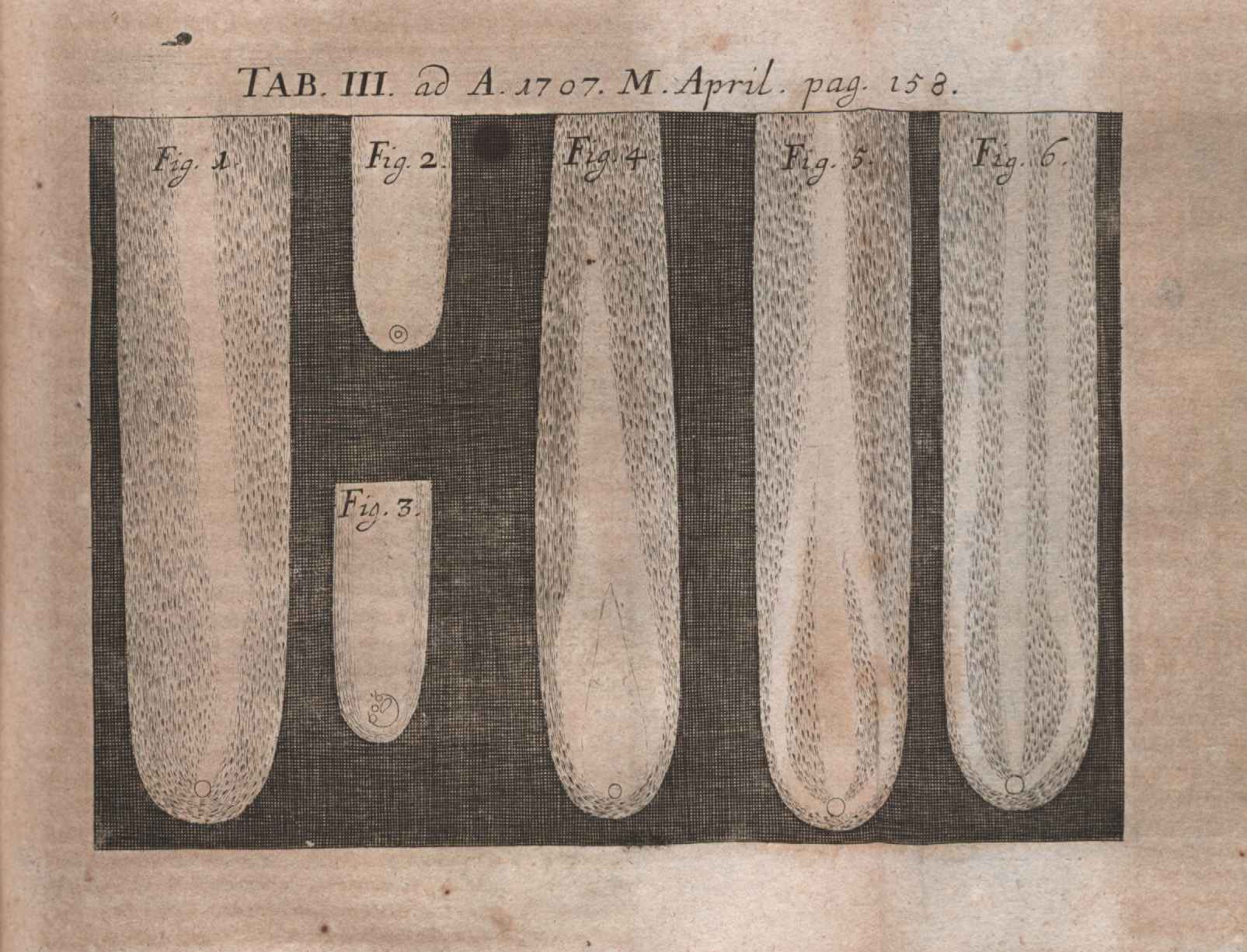

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

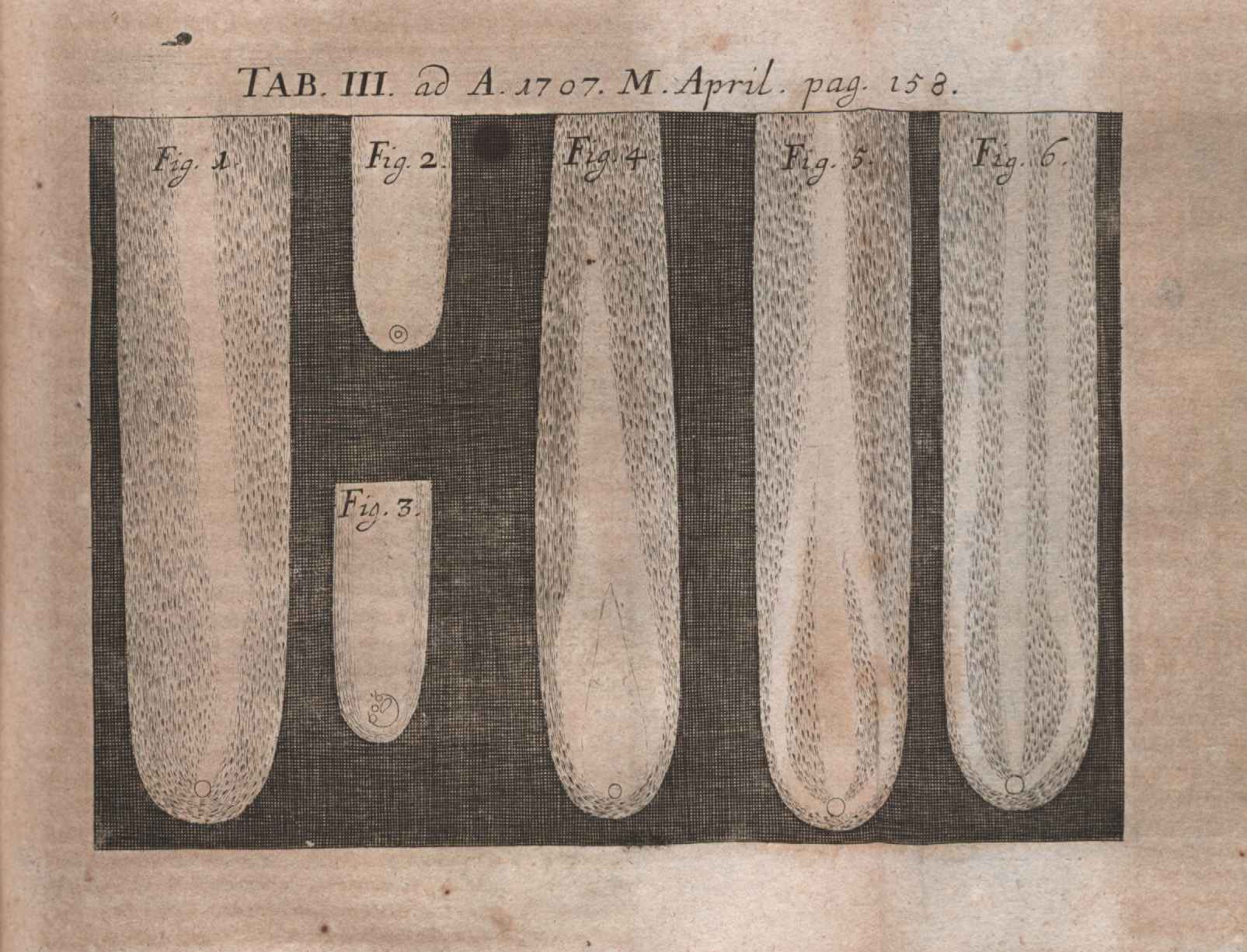

was founded in 1660, and in April 1661 the society debated a short tract on the rising of water in slender glass pipes, in which Hooke reported that the height water rose was related to the bore of the pipe (due to what is now termed capillary action

Capillary action (sometimes called capillarity, capillary motion, capillary rise, capillary effect, or wicking) is the process of a liquid flowing in a narrow space without the assistance of, or even in opposition to, any external forces li ...

). His explanation of this phenomenon was subsequently published in ''Micrography Observ.'' issue 6, in which he also explored the nature of "the fluidity of gravity". On 5 November 1661, Sir Robert Moray

Sir Robert Moray (alternative spellings: Murrey, Murray) FRS (1608 or 1609 – 4 July 1673) was a Scottish soldier, statesman, diplomat, judge, spy, and natural philosopher. He was well known to Charles I and Charles II, and to the French ...

proposed that a Curator be appointed to furnish the society with Experiments, and this was unanimously passed with Hooke being named. His appointment was made on 12 November, with thanks recorded to Dr. Boyle for releasing him to the Society's employment.

In 1664, Sir John Cutler settled an annual gratuity of fifty pounds on the Society for the founding of a ''Mechanick Lecture'', and the Fellows appointed Hooke to this task. On 27 June 1664 he was confirmed to the office, and on 11 January 1665 was named ''Curator by Office'' for life with an additional salary of £30 to Cutler's annuity.

Hooke's role at the Royal Society was to demonstrate experiments from his own methods or at the suggestion of members. Among his earliest demonstrations were discussions of the nature of air, the implosion of glass bubbles which had been sealed with comprehensive hot air, and demonstrating that the ''Pabulum vitae'' and ''flammae'' were one and the same. He also demonstrated that a dog could be kept alive with its thorax opened, provided air was pumped in and out of its lungs, and noting the difference between venous

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

and arterial

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

blood. There were also experiments on the subject of gravity, the falling of objects, the weighing of bodies and measuring of barometric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, 7 ...

at different heights, and pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward th ...

s up to .

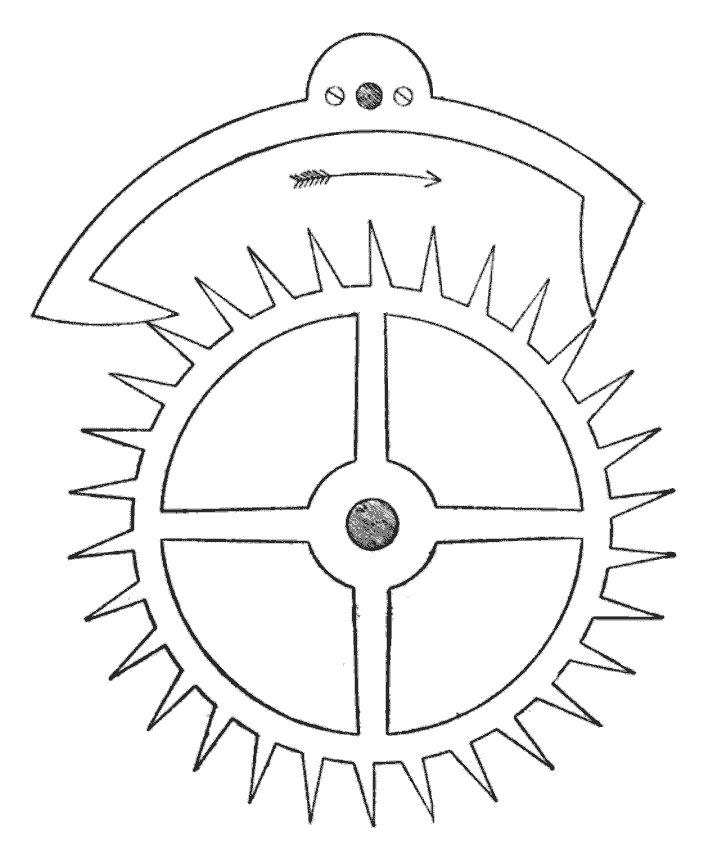

Instruments were devised to measure a second of arc

A minute of arc, arcminute (arcmin), arc minute, or minute arc, denoted by the symbol , is a unit of angular measurement equal to of one degree. Since one degree is of a turn (or complete rotation), one minute of arc is of a turn. The ...

in the movement of the sun or other stars, to measure the strength of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

, and in particular an engine to cut teeth for watches, much finer than could be managed by hand, an invention which was, by Hooke's death, in constant use.

In 1663 and 1664, Hooke made his microscopic observations, subsequently collated in ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon.'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It ...

'' in 1665.

On 20 March 1664, Hooke succeeded Arthur Dacres as Gresham Professor of Geometry

The Professor of Geometry at Gresham College, London, gives free educational lectures to the general public. The college was founded for this purpose in 1597, when it appointed seven professors; this has since increased to ten and in addition the ...

. Hooke received the degree of "Doctor of Physic" in December 1691.

Hooke and Newcomen

There is a widely reported but seemingly incorrect story that Dr Hooke corresponded withThomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen (; February 1664 – 5 August 1729) was an English inventor who created the atmospheric engine, the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. He was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling.

He ...

in connection with Newcomen's invention of the steam engine. This story was discussed by Rhys Jenkins, a past President of the Newcomen Society, in 1936. Jenkins traced the origin of the story to an article "Steam Engines" by Dr. John Robison (1739–1805) in the third edition of the "Encyclopædia Britannica”, which says ''There are to be found among Hooke's papers, in the possession of the Royal Society, some notes of observations, for the use of Newcomen, his countryman, on Papin's boasted method of transmitting to a great distance the action of an mill by means of pipes'', and that Hooke had dissuaded Newcomen from erecting a machine on this principle. Jenkins points out a number of errors in Robison's article, and questions whether the correspondent might in fact have been Newton, whom Hooke is known to have corresponded with, the name being misread as Newcomen. A search by Mr. H W Dickinson of Hooke's papers held by the Royal Society, which had been bound together in the middle of the 18th century, i.e. before Robison's time, and carefully preserved since, revealed no trace of any correspondence between Hooke and Newcomen. Jenkins concluded ''... this story must be omitted from the history of the steam engine, at any rate until documentary evidence is forthcoming.''

In the intervening years since 1936 no such evidence has been found, but the story persists. For instance, in a book published in 2011 it is said that ''in a letter dated 1703 Hooke did suggest that Newcomen use condensing steam to drive the piston.''

Personality and disputes

Reputedly, Hooke was a staunch friend and ally. In his early training atWadham College

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy W ...

, he was among ardent royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

s, particularly Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

. Yet allegedly, Hooke was also proud, and often annoyed by intellectual competitors. Hooke contended that Oldenburg Oldenburg may also refer to:

Places

*Mount Oldenburg, Ellsworth Land, Antarctica

*Oldenburg (city), an independent city in Lower Saxony, Germany

**Oldenburg (district), a district historically in Oldenburg Free State and now in Lower Saxony

*Olde ...

had leaked details of Hooke's watch escapement. Otherwise, Hooke guarded his own ideas and used ciphers

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

.

On the other hand, as the Royal Society's curator of experiments, Hooke was tasked to demonstrate many ideas sent in to the Society. Some evidence suggests that Hooke subsequently assumed credit for some of these ideas. Yet in this period of immense scientific progress, numerous ideas were developed in multiple places roughly simultaneously. Immensely busy, Hook let many of his own ideas remain undeveloped, although others he patented.

Perhaps more significantly, Hooke and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

disputed over credit for certain breakthroughs in physical science, including gravitation, astronomy, and optics. After Hooke's death, Newton questioned his legacy. And as the Royal Society's president, Newton allegedly destroyed or failed to preserve the only known portrait of Hooke. In the 20th century, researchers Robert Gunther

Robert William Theodore Gunther (23 August 1869 – 9 March 1940) was a historian of science, zoologist, and founder of the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

Gunther's father, Albert Günther, was Keeper of Zoology at the British Museu ...

and Margaret revived Hooke's legacy, establishing Hooke among the most influential scientists of his time.

None of this should distract from Hooke's inventiveness, his remarkable experimental facility, and his capacity for hard work. His ideas about gravitation, and his claim of priority for the inverse square law, are outlined below. He was granted a large number of patents for inventions and refinements in the fields of elasticity, optics, and barometry. The Royal Society's Hooke papers, rediscovered in 2006, (after disappearing when Newton took over) may open up a modern reassessment.

Much has been written about the unpleasant side of Hooke's personality, starting with comments by his first biographer, Richard Waller, that Hooke was "in person, but despicable" and "melancholy, mistrustful, and jealous." Waller's comments influenced other writers for well over two centuries, so that a picture of Hooke as a disgruntled, selfish, anti-social curmudgeon dominates many older books and articles. For example, Arthur Berry said that Hooke "claimed credit for most of the scientific discoveries of the time." Sullivan wrote that Hooke was "positively unscrupulous" and possessing an "uneasy apprehensive vanity" in dealings with Newton. Manuel used the phrase "cantankerous, envious, vengeful" in his description. More described Hooke having both a "cynical temperament" and a "caustic tongue." Andrade was more sympathetic, but still used the adjectives "difficult", "suspicious", and "irritable" in describing Hooke.

The publication of Hooke's diary in 1935 revealed previously unknown details about his social and familial relationships. Biographer Margaret argued that "the picture which is usually painted of Hooke as a morose... recluse is completely false." Hooke interacted with noted craftsmen such as

Much has been written about the unpleasant side of Hooke's personality, starting with comments by his first biographer, Richard Waller, that Hooke was "in person, but despicable" and "melancholy, mistrustful, and jealous." Waller's comments influenced other writers for well over two centuries, so that a picture of Hooke as a disgruntled, selfish, anti-social curmudgeon dominates many older books and articles. For example, Arthur Berry said that Hooke "claimed credit for most of the scientific discoveries of the time." Sullivan wrote that Hooke was "positively unscrupulous" and possessing an "uneasy apprehensive vanity" in dealings with Newton. Manuel used the phrase "cantankerous, envious, vengeful" in his description. More described Hooke having both a "cynical temperament" and a "caustic tongue." Andrade was more sympathetic, but still used the adjectives "difficult", "suspicious", and "irritable" in describing Hooke.

The publication of Hooke's diary in 1935 revealed previously unknown details about his social and familial relationships. Biographer Margaret argued that "the picture which is usually painted of Hooke as a morose... recluse is completely false." Hooke interacted with noted craftsmen such as Thomas Tompion

Thomas Tompion, FRS (1639–1713) was an English clockmaker, watchmaker and mechanician who is still regarded to this day as the "Father of English Clockmaking". Tompion's work includes some of the most historic and important clocks and watc ...

, the clockmaker, and Christopher Cocks (Cox), an instrument maker. He often met Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

, with whom he shared many interests, and had a lasting friendship with John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

. Hooke's diaries also make frequent reference to meetings at coffeehouses and taverns, and to dinners with Robert Boyle. He took tea on many occasions with his lab assistant, Harry Hunt. Although Hooke largely lived alone, apart from the servants who ran his home, his niece Grace Hooke and cousin Tom Giles lived with him for some years as children.

Hooke never married. His diary records that he sexually abused his niece Grace, who was in his custody between the ages of 10 and 17, during her teens. Hooke also had sexual relations with several maids and housekeepers, and records that one of these housekeepers gave birth to a girl, but he does not note the child's paternity.

Under the strain of an enormous workload, Hooke suffered from headaches, dizziness and bouts of insomnia. Approaching these in the same scientific spirit that he brought to his work, he experimented with self-medication, diligently recording symptoms, substances and effects in his diary. He regularly used sal ammoniac, purges and opiates, which appear to have had an increasing impact on his physical and mental health over time.

On 3 March 1703 Hooke died in London, having been blind and bedridden during the last year of his life. A chest containing £8,000 in money and gold was found in his room at Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England. It does not enroll students or award degrees. It was founded in 1596 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, and hosts ove ...

. Although he had talked of leaving a generous bequest to the Royal Society, which would have given his name to a library, laboratory and lectures, no will was found and the money passed to a cousin, Elizabeth Stephens. Hooke was buried at St Helen's Bishopsgate

St Helen's Bishopsgate is an Anglican church in London. It is located in Great St Helen's, off Bishopsgate.

It is the largest surviving parish church in the City of London. Several notable figures are buried there, and it contains more monumen ...

, but the precise location of his grave is unknown.

Science

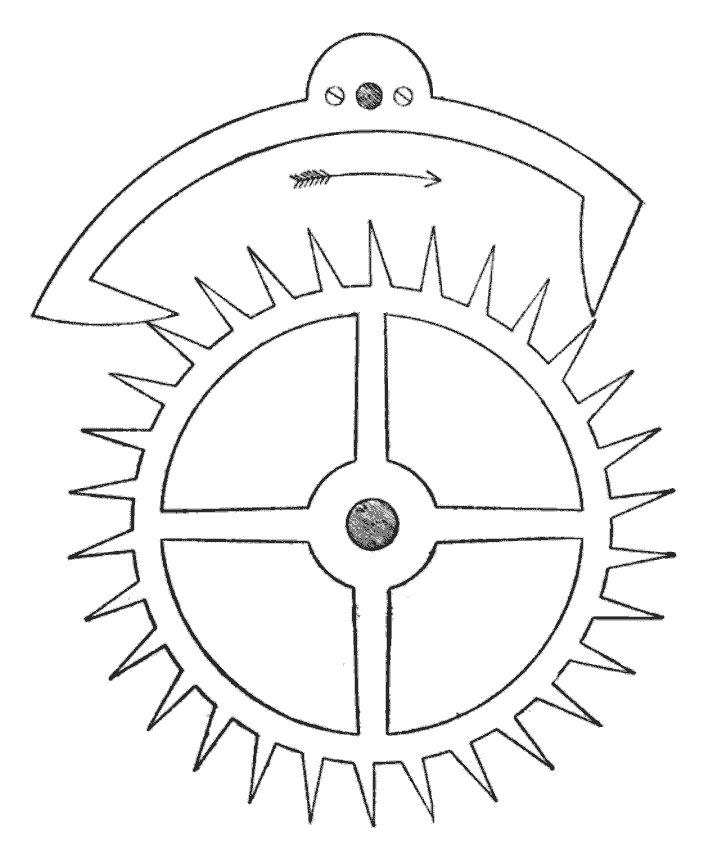

Mechanics

In 1660, Hooke discovered the law of elasticity which bears his name and which describes the linear variation oftension

Tension may refer to:

Science

* Psychological stress

* Tension (physics), a force related to the stretching of an object (the opposite of compression)

* Tension (geology), a stress which stretches rocks in two opposite directions

* Voltage or el ...

with extension in an elastic

Elastic is a word often used to describe or identify certain types of elastomer, elastic used in garments or stretchable fabrics.

Elastic may also refer to:

Alternative name

* Rubber band, ring-shaped band of rubber used to hold objects togeth ...

spring. He first described this discovery in the anagram "ceiiinosssttuv", whose solution he published in 1678 as "Ut tensio, sic vis" meaning "As the extension, so the force." Hooke's work on elasticity culminated, for practical purposes, in his development of the balance spring

A balance spring, or hairspring, is a spring attached to the balance wheel in mechanical timepieces. It causes the balance wheel to oscillate with a resonant frequency when the timepiece is running, which controls the speed at which the wheels of ...

or hairspring, which for the first time enabled a portable timepiece – a watch – to keep time with reasonable accuracy. A bitter dispute between Hooke and Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

on the priority of this invention was to continue for centuries after the death of both; but a note dated 23 June 1670 in the Hooke Folio (see ''External links'' below), describing a demonstration of a balance-controlled watch before the Royal Society, has been held to favour Hooke's claim.

Hooke first announced his law of elasticity as an anagram. This was a method sometimes used by scientists, such as Hooke, Huygens, Galileo, and others, to establish priority for a discovery without revealing details.

Hooke became Curator of Experiments in 1662 to the newly founded Royal Society, and took responsibility for experiments performed at its weekly meetings. This was a position he held for over 40 years. While this position kept him in the thick of science in Britain and beyond, it also led to some heated arguments with other scientists, such as Huygens (see above) and particularly with

Hooke first announced his law of elasticity as an anagram. This was a method sometimes used by scientists, such as Hooke, Huygens, Galileo, and others, to establish priority for a discovery without revealing details.

Hooke became Curator of Experiments in 1662 to the newly founded Royal Society, and took responsibility for experiments performed at its weekly meetings. This was a position he held for over 40 years. While this position kept him in the thick of science in Britain and beyond, it also led to some heated arguments with other scientists, such as Huygens (see above) and particularly with Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

and the Royal Society's Henry Oldenburg

Henry Oldenburg (also Henry Oldenbourg) FRS (c. 1618 as Heinrich Oldenburg – 5 September 1677), was a German theologian, diplomat, and natural philosopher, known as one of the creators of modern scientific peer review. He was one of the fo ...

. In 1664 Hooke also was appointed Professor of Geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

at Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England. It does not enroll students or award degrees. It was founded in 1596 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, and hosts ove ...

in London and Cutlerian Lecturer in Mechanics.

On 8 July 1680, Hooke observed the nodal patterns associated with the modes of vibration of glass plates. He ran a bow along the edge of a glass plate covered with flour, and saw the nodal patterns emerge.Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni,

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

''Oxford Dictionary of Scientists'', Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 101, . In acoustics, in 1681 he showed the Royal Society that musical tones could be generated from spinning brass cogs cut with teeth in particular proportions.

Gravitation

While many of his contemporaries believed in the aether as a medium for transmitting attraction or repulsion between separated celestial bodies, Hooke argued for an attracting principle of gravitation in ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon.'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It ...

'' (1665). Hooke's 1666 Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

lecture on gravity added two further principles: that all bodies move in straight lines until deflected by some force and that the attractive force is stronger for closer bodies. Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart (; 22 November 175311 June 1828) was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician. Today regarded as one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment, he was renowned as a populariser of the work of Francis Hut ...

quoted Hooke's own words on his system of the world. "I will explain," says Hooke, in a communication to the Royal Society in 1666, "a system of the world very different from any yet received. It is founded on the following positions. 1. That all the heavenly bodies have not only a gravitation of their parts to their own proper centre, but that they also mutually attract each other within their spheres of action. 2. That all bodies having a simple motion, will continue to move in a straight line, unless continually deflected from it by some extraneous force, causing them to describe a circle, an ellipse, or some other curve. 3. That this attraction is so much the greater as the bodies are nearer. As to the proportion in which those forces diminish by an increase of distance, I own I have not discovered it...."Hooke's 1670 Gresham lecture explained that gravitation applied to "all celestial bodies" and added the principles that the gravitating power decreases with distance and that in the absence of any such power bodies move in straight lines. Hooke published his ideas about the "System of the World" again in somewhat developed form in 1674, as an addition to "An Attempt to Prove the Motion of the Earth from Observations".Hooke's 1674 statement in "An Attempt to Prove the Motion of the Earth from Observations", is available i

online facsimile here

Hooke clearly postulated mutual attractions between the Sun and planets, in a way that increased with nearness to the attracting body. Hooke's statements up to 1674 made no mention, however, that an inverse square law applies or might apply to these attractions. Hooke's gravitation was also not yet universal, though it approached universality more closely than previous hypotheses. Hooke also did not provide accompanying evidence or mathematical demonstration. On these two aspects, Hooke stated in 1674: "Now what these several degrees f gravitational attractionare I have not yet experimentally verified" (indicating that he did not yet know what law the gravitation might follow); and as to his whole proposal: "This I only hint at present", "having my self many other things in hand which I would first compleat, and therefore cannot so well attend it" (i.e. "prosecuting this Inquiry"). In November 1679, Hooke initiated a remarkable exchange of letters with Newton (of which the full text is now published).Turnbull, H W (ed.) (1960), ''Correspondence of Isaac Newton'', Vol. 2 (1676–1687), Cambridge University Press, giving the Hooke-Newton correspondence (of November 1679 to January 1679/80) at pp. 297–314, and the 1686 correspondence over Hooke's priority claim at pp. 431–448. Hooke's ostensible purpose was to tell Newton that Hooke had been appointed to manage the Royal Society's correspondence. Hooke therefore wanted to hear from members about their researches, or their views about the researches of others; and as if to whet Newton's interest, he asked what Newton thought about various matters, giving a whole list, mentioning "compounding the celestial motions of the planetts of a direct motion by the tangent and an attractive motion towards the central body", and "my hypothesis of the lawes or causes of springinesse", and then a new hypothesis from Paris about planetary motions (which Hooke described at length), and then efforts to carry out or improve national surveys, the difference of latitude between London and Cambridge, and other items. Newton's reply offered "a fansy of my own" about a terrestrial experiment (not a proposal about celestial motions) which might detect the Earth's motion, by the use of a body first suspended in air and then dropped to let it fall. The main point was to indicate how Newton thought the falling body could experimentally reveal the Earth's motion by its direction of deviation from the vertical, but he went on hypothetically to consider how its motion could continue if the solid Earth had not been in the way (on a spiral path to the centre). Hooke disagreed with Newton's idea of how the body would continue to move. A short further correspondence developed, and towards the end of it Hooke, writing on 6 January 1679, 80 to Newton, communicated his "supposition ... that the Attraction always is in a duplicate proportion to the Distance from the Center Reciprocall, and Consequently that the Velocity will be in a subduplicate proportion to the Attraction and Consequently as Kepler Supposes Reciprocall to the Distance." (Hooke's inference about the velocity was actually incorrect) In 1686, when the first book of Newton's '' Principia'' was presented to the Royal Society, Hooke claimed that he had given Newton the "notion" of "the rule of the decrease of Gravity, being reciprocally as the squares of the distances from the Center". At the same time (according to

Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

's contemporary report) Hooke agreed that "the Demonstration of the Curves generated therby" was wholly Newton's.

A recent assessment about the early history of the inverse square law is that "by the late 1660s," the assumption of an "inverse proportion between gravity and the square of distance was rather common and had been advanced by a number of different people for different reasons". Newton himself had shown in the 1660s that for planetary motion under a circular assumption, force in the radial direction had an inverse-square relation with distance from the center. Newton, faced in May 1686 with Hooke's claim on the inverse square law, denied that Hooke was to be credited as author of the idea, giving reasons including the citation of prior work by others before Hooke. Newton also firmly claimed that even if it had happened that he had first heard of the inverse square proportion from Hooke, which it had not, he would still have some rights to it in view of his mathematical developments and demonstrations, which enabled observations to be relied on as evidence of its accuracy, while Hooke, without mathematical demonstrations and evidence in favour of the supposition, could only guess (according to Newton) that it was approximately valid "at great distances from the center".

On the other hand, Newton did accept and acknowledge, in all editions of the ''Principia'', that Hooke (but not exclusively Hooke) had separately appreciated the inverse square law in the solar system. Newton acknowledged Wren, Hooke and Halley in this connection in the Scholium to Proposition 4 in Book 1. Newton also acknowledged to Halley that his correspondence with Hooke in 1679–80 had reawakened his dormant interest in astronomical matters, but that did not mean, according to Newton, that Hooke had told Newton anything new or original: "yet am I not beholden to him for any light into that business but only for the diversion he gave me from my other studies to think on these things & for his dogmaticalness in writing as if he had found the motion in the Ellipsis, which inclined me to try it."

One of the contrasts between the two men was that Newton was primarily a pioneer in mathematical analysis and its applications as well as optical experimentation, while Hooke was a creative experimenter of such great range, that it is not surprising to find that he left some of his ideas, such as those about gravitation, undeveloped. This in turn makes it understandable how in 1759, decades after the deaths of both Newton and Hooke, Alexis Clairaut

Alexis Claude Clairaut (; 13 May 1713 – 17 May 1765) was a French mathematician, astronomer, and geophysicist. He was a prominent Newtonian whose work helped to establish the validity of the principles and results that Sir Isaac Newton had ou ...

, mathematical astronomer eminent in his own right in the field of gravitational studies, made his assessment after reviewing what Hooke had published on gravitation. "One must not think that this idea ... of Hooke diminishes Newton's glory", Clairaut wrote; "The example of Hooke" serves "to show what a distance there is between a truth that is glimpsed and a truth that is demonstrated".

Horology

Hooke made tremendously important contributions to the science of timekeeping, being intimately involved in the advances of his time; the introduction of the pendulum as a better regulator for clocks, the balance spring to improve the timekeeping of watches, and the proposal that a precise timekeeper could be used to find the longitude at sea.Anchor escapement

In 1655, according to his autobiographical notes, Hooke began to acquaint himself with astronomy, through the good offices of John Ward. Hooke applied himself to the improvement of the

In 1655, according to his autobiographical notes, Hooke began to acquaint himself with astronomy, through the good offices of John Ward. Hooke applied himself to the improvement of the pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward th ...

and in 1657 or 1658, he began to improve on pendulum mechanisms, studying the work of Giovanni Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion ...

, and going on to study both gravitation and the mechanics of timekeeping.

Henry Sully, writing in Paris in 1717, described the anchor escapement

In horology, the anchor escapement is a type of escapement used in pendulum clocks. The escapement is a mechanism in a mechanical clock that maintains the swing of the pendulum by giving it a small push each swing, and allows the clock's wheels ...

as ''an admirable invention of which Dr. Hooke, formerly professor of geometry in Gresham College at London, was the inventor.'' William Derham

William Derham FRS (26 November 16575 April 1735)Smolenaars, Marja.Derham, William (1657–1735), ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 26 May 2007. was an English clergyman, natural theologian, n ...

also attributes it to Hooke.

Watch balance spring

Hooke recorded that he conceived of a way to determine

Hooke recorded that he conceived of a way to determine longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

(then a critical problem for navigation), and with the help of Boyle and others he attempted to patent it. In the process, Hooke demonstrated a pocket-watch of his own devising, fitted with a coil spring

A selection of conical coil springs

The most common type of spring is the coil spring, which is made out of a long piece of metal that is wound around itself.

Coil springs were in use in Roman times, evidence of this can be found in bronze Fib ...

attached to the arbour of the balance. Hooke's ultimate failure to secure sufficiently lucrative terms for the exploitation of this idea resulted in its being shelved, and evidently caused him to become more jealous of his inventions.

Hooke developed the balance spring

A balance spring, or hairspring, is a spring attached to the balance wheel in mechanical timepieces. It causes the balance wheel to oscillate with a resonant frequency when the timepiece is running, which controls the speed at which the wheels of ...

independently of and at least 5 years before Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

, who published his own work in ''Journal de Scavans'' in February 1675.

Microscopy

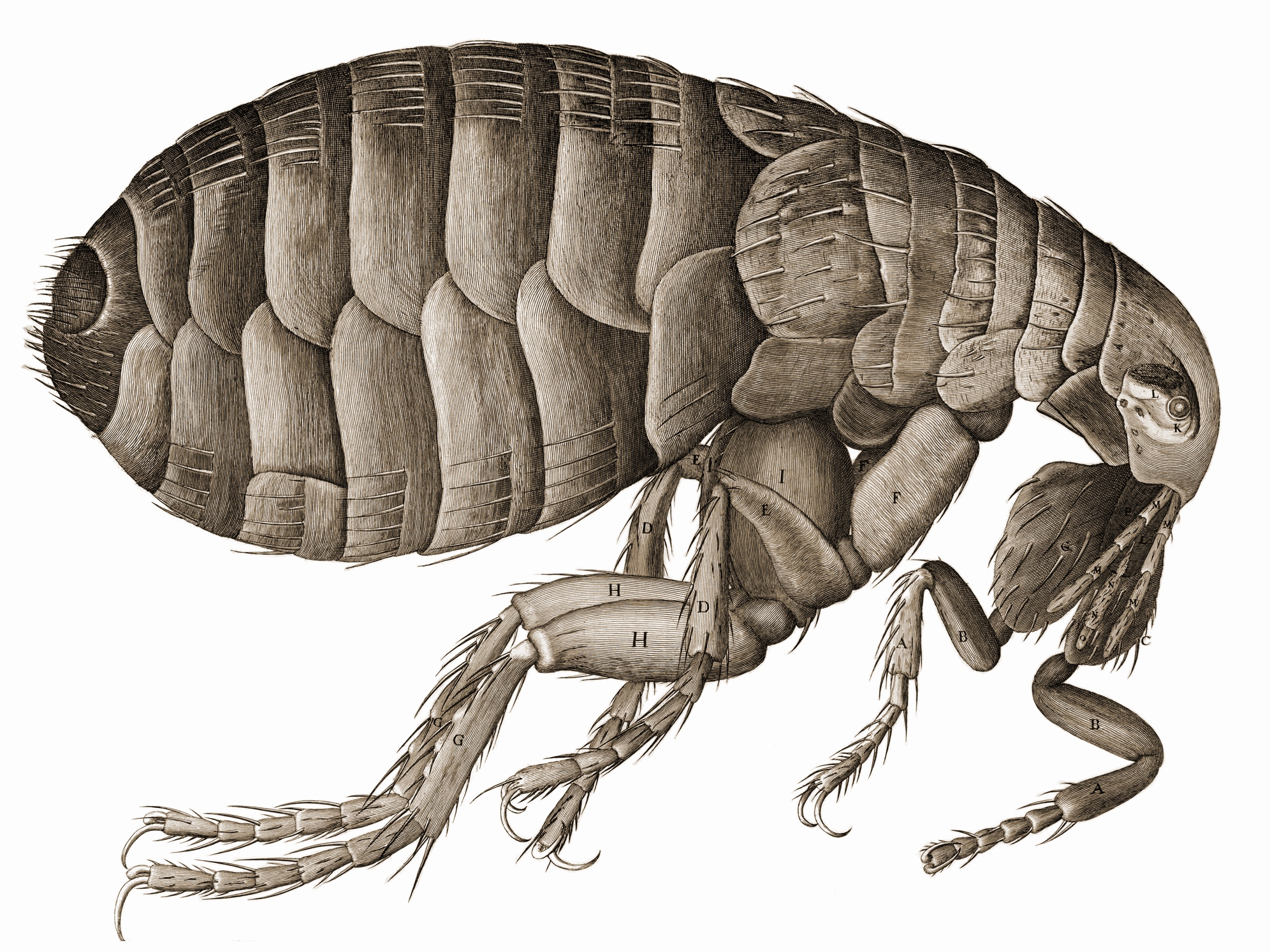

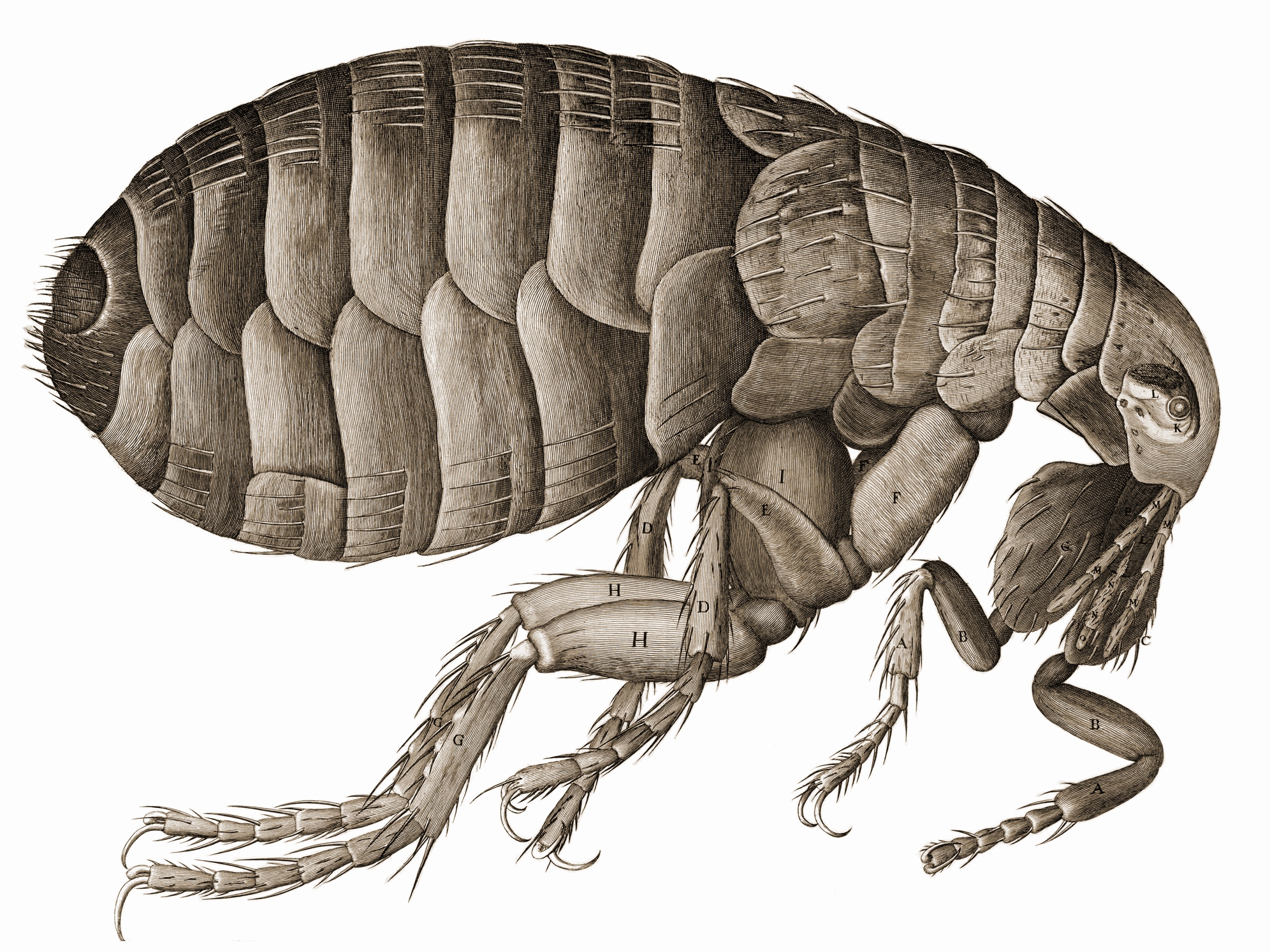

Hooke's 1665 book ''

Hooke's 1665 book ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon.'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It ...

'', describing observations with microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

s and telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

s, as well as original work in biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, contains the earliest of an observed microorganism, a microfungus ''Mucor

''Mucor'' is a microbial genus of approximately 40 species of molds in the family Mucoraceae. Species are commonly found in soil, digestive systems, plant surfaces, some cheeses like Tomme de Savoie, rotten vegetable matter and iron oxide re ...

''. Hooke coined the term ''cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

'', suggesting plant structure's resemblance to honeycomb

A honeycomb is a mass of Triangular prismatic honeycomb#Hexagonal prismatic honeycomb, hexagonal prismatic Beeswax, wax cells built by honey bees in their beehive, nests to contain their larvae and stores of honey and pollen.

beekeeping, Beekee ...

cells. The hand-crafted, leather and gold-tooled microscope he used to make the observations for ''Micrographia'', originally constructed by Christopher White in London, is on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine

The National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) is a museum in Silver Spring, Maryland, near Washington, DC. The museum was founded by U.S. Army Surgeon General William A. Hammond as the Army Medical Museum (AMM) in 1862; it became the NMHM in ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

.

''Micrographia'' also contains Hooke's, or perhaps Boyle and Hooke's, ideas on combustion. Hooke's experiments led him to conclude that combustion involves a substance that is mixed with air, a statement with which modern scientists would agree, but that was not understood widely, if at all, in the seventeenth century. Hooke went on to conclude that respiration also involves a specific component of the air. Partington even goes so far as to claim that if "Hooke had continued his experiments on combustion it is probable that he would have discovered oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

".

Palaeontology

One of the observations in ''Micrographia'' was of

One of the observations in ''Micrographia'' was of fossil wood

Fossil wood, also known as fossilized tree, is wood that is preserved in the fossil record. Over time the wood will usually be the part of a plant that is best preserved (and most easily found). Fossil wood may or may not be petrified, in ...

, the microscopic structure of which he compared to ordinary wood. This led him to conclude that fossilised objects like petrified wood and fossil shells, such as Ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

, were the remains of living things that had been soaked in petrifying water laden with minerals. Hooke believed that such fossils provided reliable clues to the past history of life on Earth, and, despite the objections of contemporary naturalists like John Ray who found the concept of extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

theologically unacceptable, that in some cases they might represent species that had become extinct through some geological disaster.

Charles Lyell wrote the following in his ''Principles of Geology'' (1832).

'The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke M.D.,'... appeared in 1705, containing 'A Discourse of Earthquakes'... His treatise... is the most philosophical production of that age, in regard to the causes of former changes in the organic and inorganic kingdoms of nature. 'However trivial a thing,' he says, 'a rotten shell may appear to some, yet these monuments of nature are more certain tokens of antiquity than coins or medals, since the best of those may be counterfeited or made by art and design, as may also books, manuscripts, and inscriptions, as all the learned are now sufficiently satisfied has often been actually practised,' &c.; 'and though it must be granted that it is very difficult to read them and to raise a chronology out of them, and to state the intervals of the time wherein such or such catastrophes and mutations have happened, yet it is not impossible.

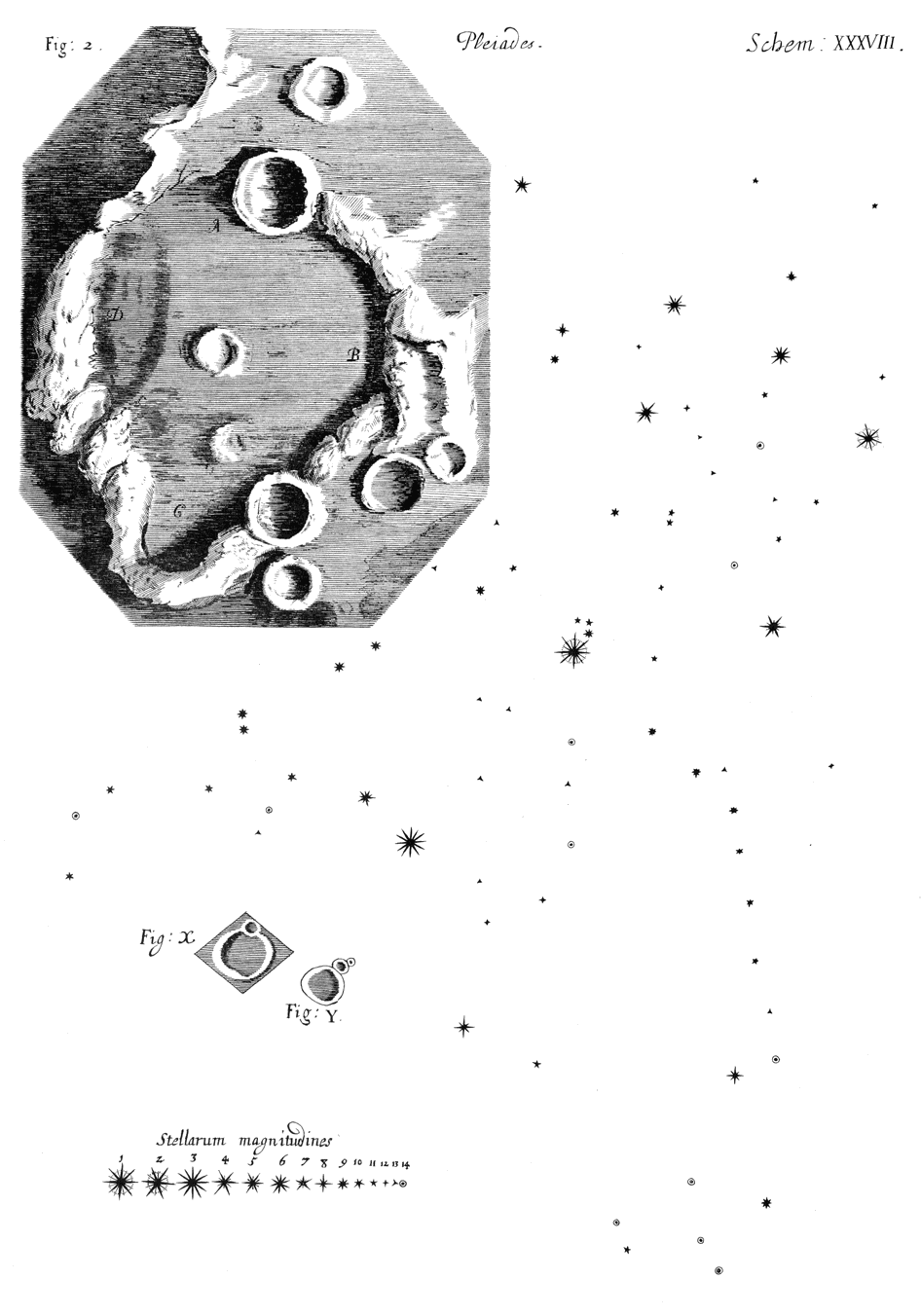

Astronomy

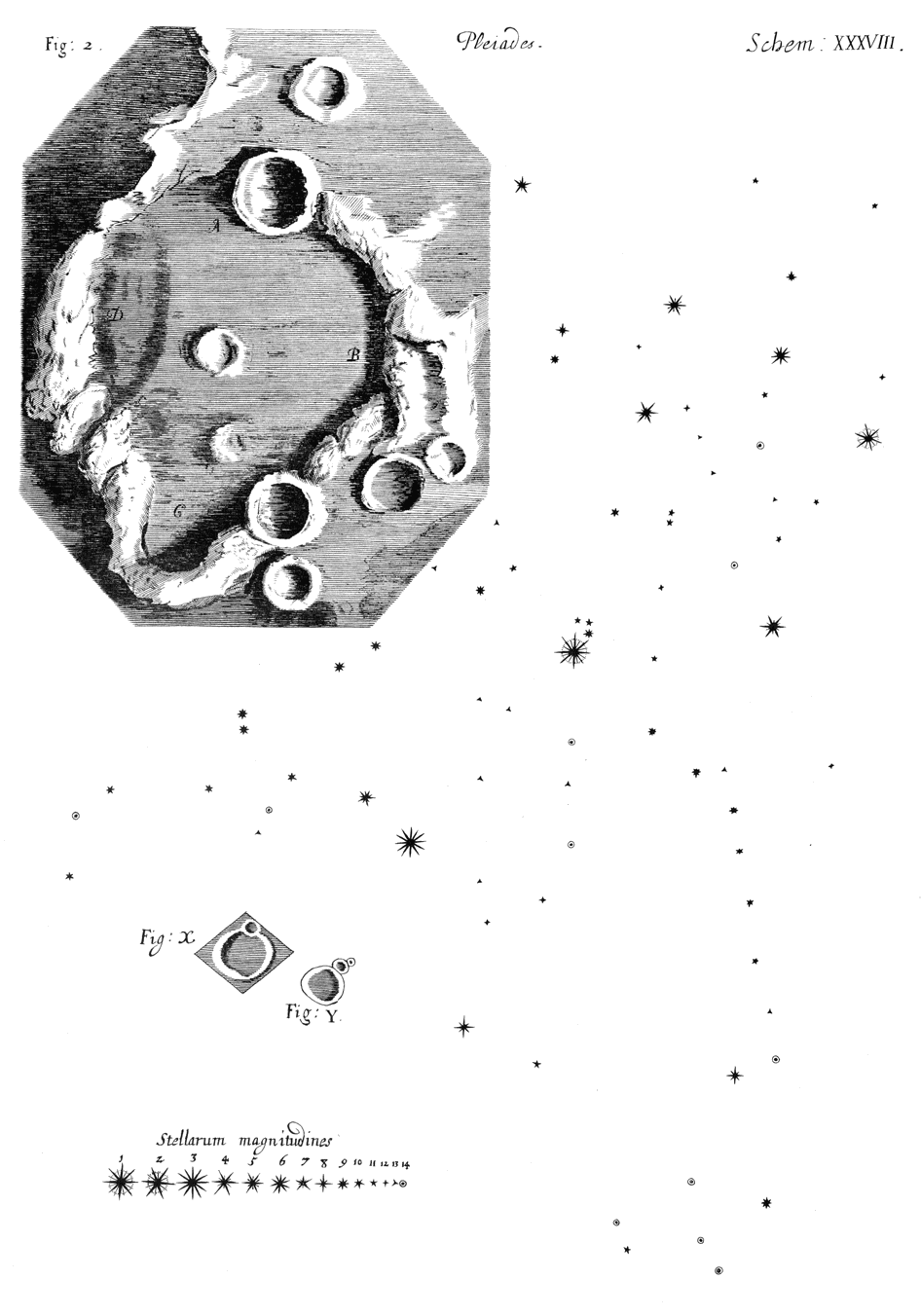

One of the more-challenging problems tackled by Hooke was the measurement of the distance to a star (other than the Sun). The star chosen was

One of the more-challenging problems tackled by Hooke was the measurement of the distance to a star (other than the Sun). The star chosen was Gamma Draconis

Gamma Draconis (γ Draconis, abbreviated Gamma Dra, γ Dra), formally named Eltanin , is a star in the northern constellation of Draco. Contrary to its gamma-designation (historically third-ranked), it is the brightest star in Draco at ...

and the method to be used was parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

determination. After several months of observing, in 1669, Hooke believed that the desired result had been achieved. It is now known that Hooke's equipment was far too imprecise to allow the measurement to succeed. Gamma Draconis was the same star James Bradley

James Bradley (1692–1762) was an English astronomer and priest who served as the third Astronomer Royal from 1742. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light (1725–1728), and the nutation of th ...

used in 1725 in discovering the aberration of light

In astronomy, aberration (also referred to as astronomical aberration, stellar aberration, or velocity aberration) is a phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects about their true positions, dependent on the velocity of t ...

.

Hooke's activities in astronomy extended beyond the study of stellar distance. His ''Micrographia'' contains illustrations of the Pleiades

The Pleiades (), also known as The Seven Sisters, Messier 45 and other names by different cultures, is an asterism and an open star cluster containing middle-aged, hot B-type stars in the north-west of the constellation Taurus. At a distance ...

star cluster as well as of lunar craters

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

. He performed experiments to study how such craters might have formed. Hooke also was an early observer of the rings of Saturn

The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit around Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entir ...

, and discovered one of the first observed double-star

In observational astronomy, a double star or visual double is a pair of stars that appear close to each other as viewed from Earth, especially with the aid of optical telescopes.

This occurs because the pair either forms a binary star (i.e. a ...

systems, Gamma Arietis

Gamma Arietis (γ Arietis, abbreviated Gamma Ari, γ Ari) is a binary star (possibly trinary) in the northern constellation of Aries. The two components are designated γ1 Arietis or Gamma Arietis B and γ2 Arietis or Gamma Arie ...

, in 1664.

Memory

A lesser-known contribution, however one of the first of its kind, was Hooke's scientific model of humanmemory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

. Hooke in a 1682 lecture to the Royal Society proposed a mechanistic model of human memory, which would bear little resemblance to the mainly philosophical models before it. This model addressed the components of encoding, memory capacity, repetition, retrieval, and forgetting – some with surprising modern accuracy. This work, overlooked for nearly 200 years, shared a variety of similarities with Richard Semon

Richard Wolfgang Semon (22 August 1859, in Berlin – 27 December 1918, in Munich) was a German zoologist, explorer, evolutionary biologist, a memory researcher who believed in the inheritance of acquired characteristics and applied this to social ...

's work of 1919/1923, both assuming memories were physical and located in the brain. The model's more interesting points are that it (1) allows for attention and other top-down influences on encoding; (2) it uses resonance to implement parallel, cue-dependent retrieval; (3) it explains memory for recency; (4) it offers a single-system account of repetition and priming, and (5) the power law of forgetting can be derived from the model's assumption in a straightforward way. This lecture would be published posthumously in 1705 as the memory model was unusually placed in a series of works on the nature of light. It has been speculated that this work saw little review as the printing was done in small batches in a post-Newtonian age of science and was most likely deemed out of date by the time it was published. Further interfering with its success was contemporary memory psychologists' rejection of immaterial souls, which Hooke invoked to some degree in regards to the processes of attention, encoding and retrieval.

Architecture

Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

, in which capacity he helped Wren rebuild London after the Great Fire in 1666, and also worked on the design of London's Monument to the fire, the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Montagu House in Bloomsbury, and the Bethlem Royal Hospital

Bethlem Royal Hospital, also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam, is a psychiatric hospital in London. Its famous history has inspired several horror books, films and TV series, most notably '' Bedlam'', a 1946 film with ...

(which became known as 'Bedlam'). Other buildings designed by Hooke include The Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

(1679), Ragley Hall

Ragley Hall in the parish of Arrow in Warwickshire is a stately home, located south of Alcester and eight miles (13 km) west of Stratford-upon-Avon. It is the ancestral seat of the Seymour-Conway family, Marquesses of Hertford.

History

...

in Warwickshire, Ramsbury Manor

Ramsbury Manor is a Grade I listed country house at Ramsbury, Wiltshire, on the River Kennet between Hungerford and Marlborough, in the south of England.

It belongs to the Capricorn Foundation, a trust which has the task of maintaining the ho ...

in Wiltshire and the parish church of St Mary Magdalene at Willen

Willen is a district of Milton Keynes, England and is also one of the ancient villages of Buckinghamshire to have been included in the designated area of the New City in 1967. At the 2011 Census the population of the district was included in t ...

in Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

. Hooke's collaboration with Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

also included St Paul's Cathedral, whose dome uses a method of construction conceived by Hooke. Hooke also participated in the design of the Pepys Library, which held the manuscripts of Samuel Pepys' diaries, the most frequently cited eyewitness account of the Great Fire of London.

Hooke and Wren both being keen astronomers, the Monument was designed to serve a scientific function as a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...