Robert Henryson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Henryson ( Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the

Robert Henryson ( Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the

There is no record of when or where Henryson was born or educated. The earliest found unconfirmed reference to him occurs on 10 September 1462, when a man of his name with license to teach is on record as having taken a post in the recently founded University of Glasgow. If this was the poet, as is usually assumed, then the citation indicates that he had completed studies in both

There is no record of when or where Henryson was born or educated. The earliest found unconfirmed reference to him occurs on 10 September 1462, when a man of his name with license to teach is on record as having taken a post in the recently founded University of Glasgow. If this was the poet, as is usually assumed, then the citation indicates that he had completed studies in both

Dunfermline's Carnegie Public Lending Library

has a special Henryson collection which can be consulted by appointment.

Britain in Print

has an online audio recording of Henryson's ''The Testament of Cresseid'' read by Colin Donati and Dr Morna Fleming among its resources.

Robert Henryson Society homepage

digital edition at the

Robert L. Kindrick, 'The Morall Fabillis: Introduction"Writers' Museum

in Edinburgh commemorates Robert Henryson in its Makars' Court in

Robert Henryson ( Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the

Robert Henryson ( Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

'' makars'', he lived in the royal burgh

A royal burgh () was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in the Northern Renaissance at a time when the culture was on a cusp between medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and renaissance sensibilities. Little is known of his life, but evidence suggests that he was a teacher who had training in law and the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

, that he had a connection with Dunfermline Abbey and that he may also have been associated for a period with Glasgow University

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

. His poetry was composed in Middle Scots at a time when this was the state language. His writing consists mainly of narrative works. His surviving body of work amounts to almost 5000 lines.

Works

Henryson's surviving canon consists of threelong poem

The long poem is a literary genre including all poetry of considerable length. Though the definition of a long poem is vague and broad and unnecessary, the genre includes some of the most important poetry ever written.

With more than 220,000 (10 ...

s and around twelve miscellaneous short works in various genres. The longest poem is his ''Morall Fabillis

''The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian'' is a work of Northern Renaissance literature composed in Middle Scots by the fifteenth century Scottish makar, Robert Henryson. It is a cycle of thirteen connected narrative poems based on fables f ...

,'' a tight, intricately structured set of thirteen fable stories in a cycle

Cycle, cycles, or cyclic may refer to:

Anthropology and social sciences

* Cyclic history, a theory of history

* Cyclical theory, a theory of American political history associated with Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.

* Social cycle, various cycles in soc ...

that runs just short of 3000 lines. Two other long works survive, both a little over 600 lines each. One is '' The Tale of Orpheus and Erudices his Quene,'' his dynamic and inventive version of the Orpheus story. The other is his '' Testament of Cresseid'', a tale of moral and psychological subtlety in a tragic mode founded upon the literary conceit of "completing" Criseyde's story-arc from Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde. Emily Wingfield has explored its significance in relation to the deployment of the Trojan Legend in political discourse between England and Scotland.

The range of Henryson's shorter works includes '' Robene and Makyne,'' a pastourelle

The pastourelle (; also ''pastorelle'', ''pastorella'', or ''pastorita'' is a typically Old French lyric form concerning the romance of a shepherdess. In most of the early pastourelles, the poet knight meets a shepherdess who bests him in a bat ...

on a theme of love, as well as a bawdy passage of comic flyting which targets the medical practises of his day, a highly crafted and compressed poem of Marian

Marian may refer to:

People

* Mari people, a Finno-Ugric ethnic group in Russia

* Marian (given name), a list of people with the given name

* Marian (surname), a list of people so named

Places

*Marian, Iran (disambiguation)

* Marian, Queensla ...

devotion, some allegorical works, some philosophical meditations, and a prayer against the pest

Pest or The Pest may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Pest (organism), an animal or plant deemed to be detrimental to humans or human concerns

** Weed, a plant considered undesirable

* Infectious disease, an illness resulting from an infection

** ...

. As with his longer works, his outward themes often carry important subtexts.

Constructing a sure chronology for Henryson's writings is not possible, but his Orpheus story may have been written earlier in his career, during his time in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

, since one of its principal sources was contained in the university library. Internal evidence has been used to suggest that the ''Morall Fabillis'' were composed during the 1480s.

Biographical inferences

There is no record of when or where Henryson was born or educated. The earliest found unconfirmed reference to him occurs on 10 September 1462, when a man of his name with license to teach is on record as having taken a post in the recently founded University of Glasgow. If this was the poet, as is usually assumed, then the citation indicates that he had completed studies in both

There is no record of when or where Henryson was born or educated. The earliest found unconfirmed reference to him occurs on 10 September 1462, when a man of his name with license to teach is on record as having taken a post in the recently founded University of Glasgow. If this was the poet, as is usually assumed, then the citation indicates that he had completed studies in both arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both ...

and canon law.

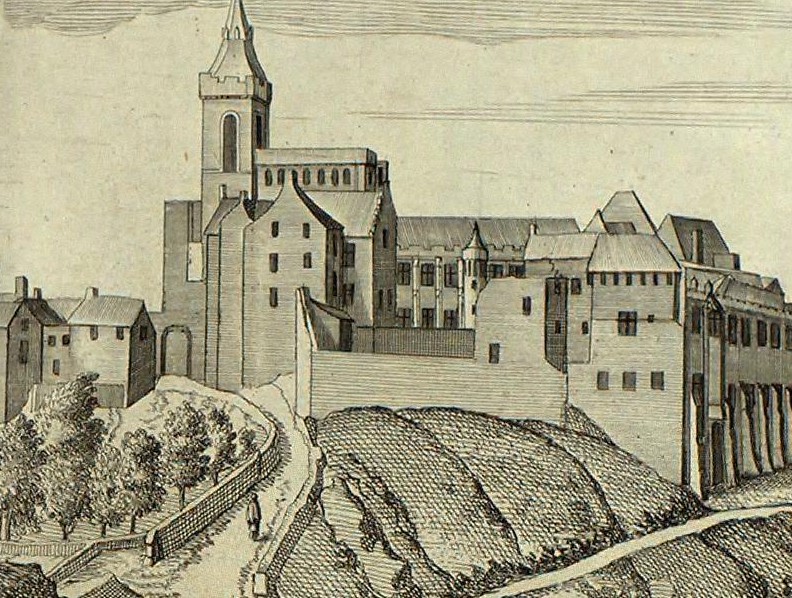

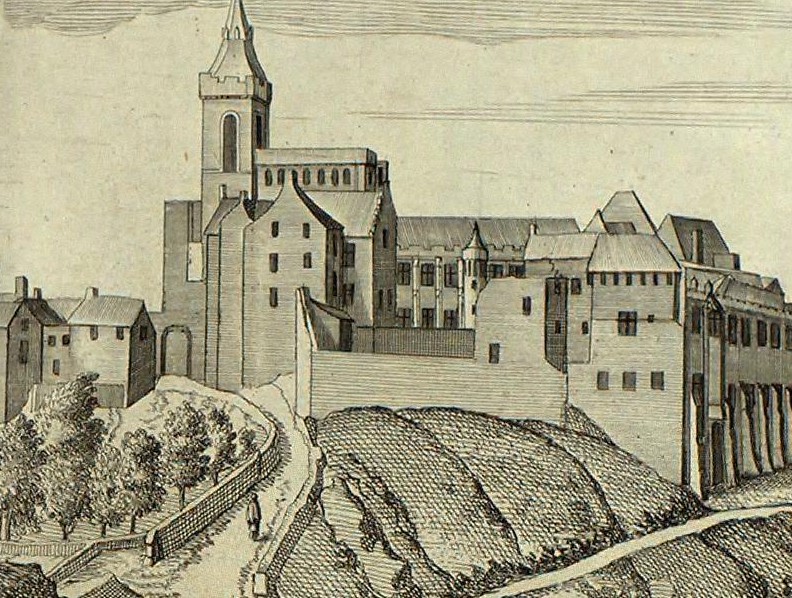

Almost all early references to Henryson firmly associate his name with Dunfermline. He probably had some attachment to the city's Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, found ...

abbey, the burial place for many of the kingdom's monarchs and an important centre for pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

close to a major ferry-crossing ''en route'' to St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

. Direct unconfirmed evidence for this connection occurs in 1478 when his name appears as a witness on abbey charters. If this was the poet, then it would establish that one of his functions was as notary for the abbey, an institution which possessed and managed a vast portfolio of territory across Scotland.

The almost universal references to Henryson as schoolmaster are usually taken to mean that he taught in and had some duty to run the grammar school for Dunfermline's abbatial burgh. A partial picture of what this meant in practice may be derived from a ''confirmatio'' of 1468 which granted provision to build a "suitable" house for the habitation of a "priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

" (as master of grammar) and "scholars" in Dunfermline, including "poor scholars being taught free of charge".

Dunfermline, as a royal burgh

A royal burgh () was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

with capital status, was routinely visited by the court with residences directly linked to the abbey complex. There is no record of Henryson as a court poet, but the close proximity makes acquaintance with the royal household likely. He was active during the reigns of James III and James IV, both of whom had strong interests in literature.

According to the poet William Dunbar, Henryson died in Dunfermline. An apocryphal story by the English poet Francis Kynaston

Sir Francis Kynaston or Kinaston (1587–1642) was an English lawyer, courtier, poet and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1621 to 1622. He is noted for his translation of Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Troilus and Criseyde'' into Latin vers ...

in the early 17th century refers to the flux as the cause of death, but this has not been established. The year of death also is unknown, although c.1498-9, a time of plague in the burgh, has been tentatively suggested. However, Dunbar gives the terminus ad quem in a couplet (usually considered to have been composed c.1505) which simply states that Death ''in Dunfermelyne

:''...hes done roune'' (has whispered in private)

:''with Maister Robert Henrysoun''.

(William Dunbar, '' Lament for the Makaris'', lines 81–2)

Almost nothing else is known of Henryson outside of his surviving writing. It is not known if he originated from Dunfermline and a suggestion that he may have been linked to the Fife branch of the Clan Henderson is not possible to verify, although his name is certainly of that ilk.

General style

Henryson generally wrote in a first-person voice using a familiar tone that quickly brings the reader into his confidence and gives a notable impression of authentic personality and beliefs. The writing stays rooted in daily life and continues to feel grounded even when the themes are metaphysical or elements are fantastic. His language is a supple, flowing and conciseScots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

that clearly shows he knew Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

, while scenes are usually given a deftly evocative Scottish setting which can only have come from close connection and observation. This detailed, intimate and realistic approach, at times, strongly suggests matters of personal experience and attitudes to actual contemporary events, yet the specifics remain elusive in ways that tantalise readers and critics. Some of this sense of intrigue may be in part accidental, but it is also heightened by his cannily controlled application of a philosophy of fiction, a frequently self-proclaimed feature of the work.

No concrete details of his life can be directly inferred from his works, but there are some passages of self-reflection that appear to contain autobiographical implications, particularly in the opening stanzas of his ''Testament of Cresseid''.

Henryson's Scots

Henryson wrote using theScots language

Scots (endonym: ''Scots''; gd, Albais, ) is an Anglic language, Anglic Variety (linguistics), language variety in the West Germanic language, West Germanic language family, spoken in Scotland and parts of Ulster in the north of Ireland (wher ...

of the 15th century. This was in an age when the use of vernacular languages for literature in many parts of Europe was increasingly taking the place of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

, the long-established lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

across the continent.

Extant poems

All known and extant writings attributed to Robert Henryson are listed here. In addition, the scholar Matthew P McDiarmid identified from an index a lost poem by Henryson which began: ''On fut by Forth as I couth found'' (not listed below).McDiarmid, M.P. 1981: ''Robert Henryson,'' Scottish Academic Press, p.4Long works

* '' The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian'' ''(See below for list of individual fables in the cycle)'' * '' The Tale of Orpheus and Erudices his Quene'' * '' The Testament of Cresseid''Short works

* '' Robene and Makyne'' * '' Sum Practysis of Medecyne'' * '' The Annuciation'' * '' Ane Prayer for the Pest'' * '' The Garment of Gud Ladeis'' * '' The Bludy Serk'' * '' The Thre Deid-Pollis'' * '' Against Hasty Credence'' * '' The Abbay Walk'' * '' The Praise of Age'' * '' The Ressoning Betwix Aige and Yowth'' * '' The Ressoning Betwix Deth and Man''Individual fables

Seven of the stories in Henryson's cycle are Aesopian fables derived from elegiac Romulus texts, while the other six (given in italics) are Reynardian in genre. The three titles given with bold numbers provide evidence for the integral unity of the overall structure. * 01 The Cock and the Jasp * 02 The Twa Mice * 03 '' The Cock and the Fox'' * 04 '' The Confession of the Tod'' * 05 '' The Trial of the Tod'' * 06The Sheep and the Dog

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in ...

* 07 The Lion and the Mouse

* 08 The Preaching of the Swallow

* 09 '' The Fox the Wolf and the Cadger''

* 10 '' The Fox the Wolf and the Husbandman''

* 11 '' The Wolf and the Wether''

* 12 The Wolf and the Lamb

* 13 The Paddock and the Mouse

Bibliography

* Gray, Douglas (1979), ''Robert Henryson'', E.J. Brill, * Barron, W.R.J. (ed.) (1981), ''Robert Henryson: Selected Poems'', Carcanet New Press * McDiarmid, Matthew P. (1981), ''Robert Henryson'',Scottish Academic Press

Scottish Academic Press is an old Scottish publishing company. It is based in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the ...

,

* Fox, Denton (ed.) (1981), ''The Poems of Robert Henryson'', Clarendon Press,

* David Murison (ed.) (1989), ''Selected Poems by Robert Henryson'', The Saltire Society,

* Fleming, Morna (ed.) (2003), ''The Flouer o Makarheid'', The Robert Henryson Society, Dunfermline

* Wingfield, Emily (2014), ''The Trojan Legend in Medieval Scottish Literature'', D.S. Brewer,

See also

* Scotland's Education Act of 1496 * Scotland in the Late Middle Ages * ScotsounNotes and references

External links

Dunfermline's Carnegie Public Lending Library

has a special Henryson collection which can be consulted by appointment.

Britain in Print

has an online audio recording of Henryson's ''The Testament of Cresseid'' read by Colin Donati and Dr Morna Fleming among its resources.

Robert Henryson Society homepage

digital edition at the

National Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS) ( gd, Leabharlann Nàiseanta na h-Alba, sco, Naitional Leebrar o Scotland) is the legal deposit library of Scotland and is one of the country's National Collections. As one of the largest libraries in the ...

contains the following works by Henryson:

**The Praise of Age

**Orpheus and Eurydice

**The Want of Wise Men

;More information can also be found at: Robert L. Kindrick, 'The Morall Fabillis: Introduction"

in Edinburgh commemorates Robert Henryson in its Makars' Court in

Lady Stair's Close

Lady Stair's Close (477 Lawnmarket) is a close in Edinburgh, Scotland, just off the Royal Mile, close to the entrance to Gladstone's Land. Most notably it contains the Scottish Writers' Museum.

History

Located in Edinburgh's Lawnmarket, Lady ...

. Selections for Makars' Court are made by The Writers' Museum

The Writers’ Museum, housed in Lady Stair’s House, Lady Stair's House at the Lawnmarket on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, presents the lives of three of the foremost Scottish writers: Robert Burns, Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson. Run ...

, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henryson, Robert

Scottish Renaissance writers

Middle Scots poets

Scots Makars

1420s births

1500s deaths

Fabulists

Lallans poets

Scottish educators

Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, h ...

People associated with Fife

People associated with the University of Glasgow

People from Dunfermline

Alumni of the University of St Andrews

15th-century Scottish poets

15th-century Scottish writers