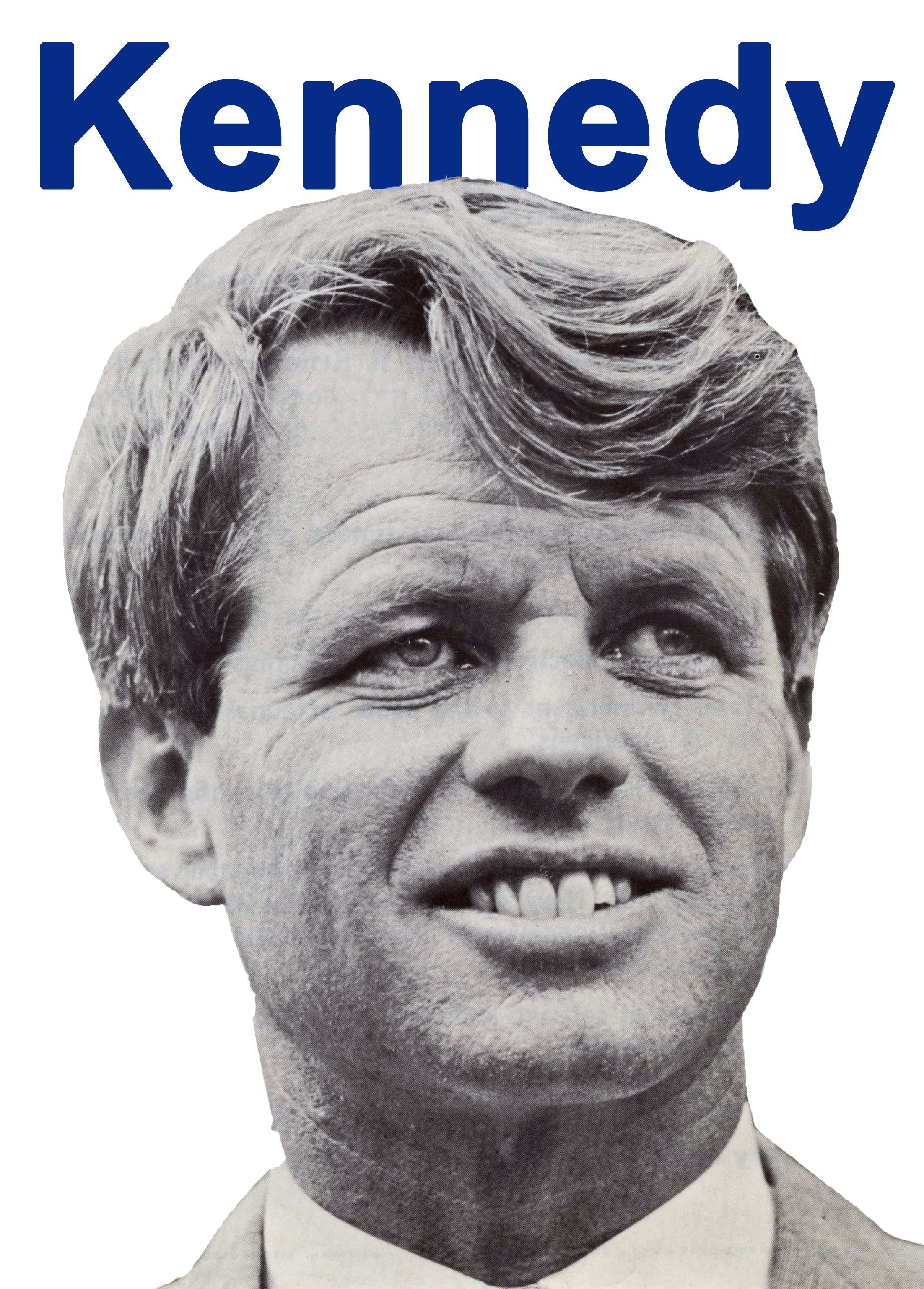

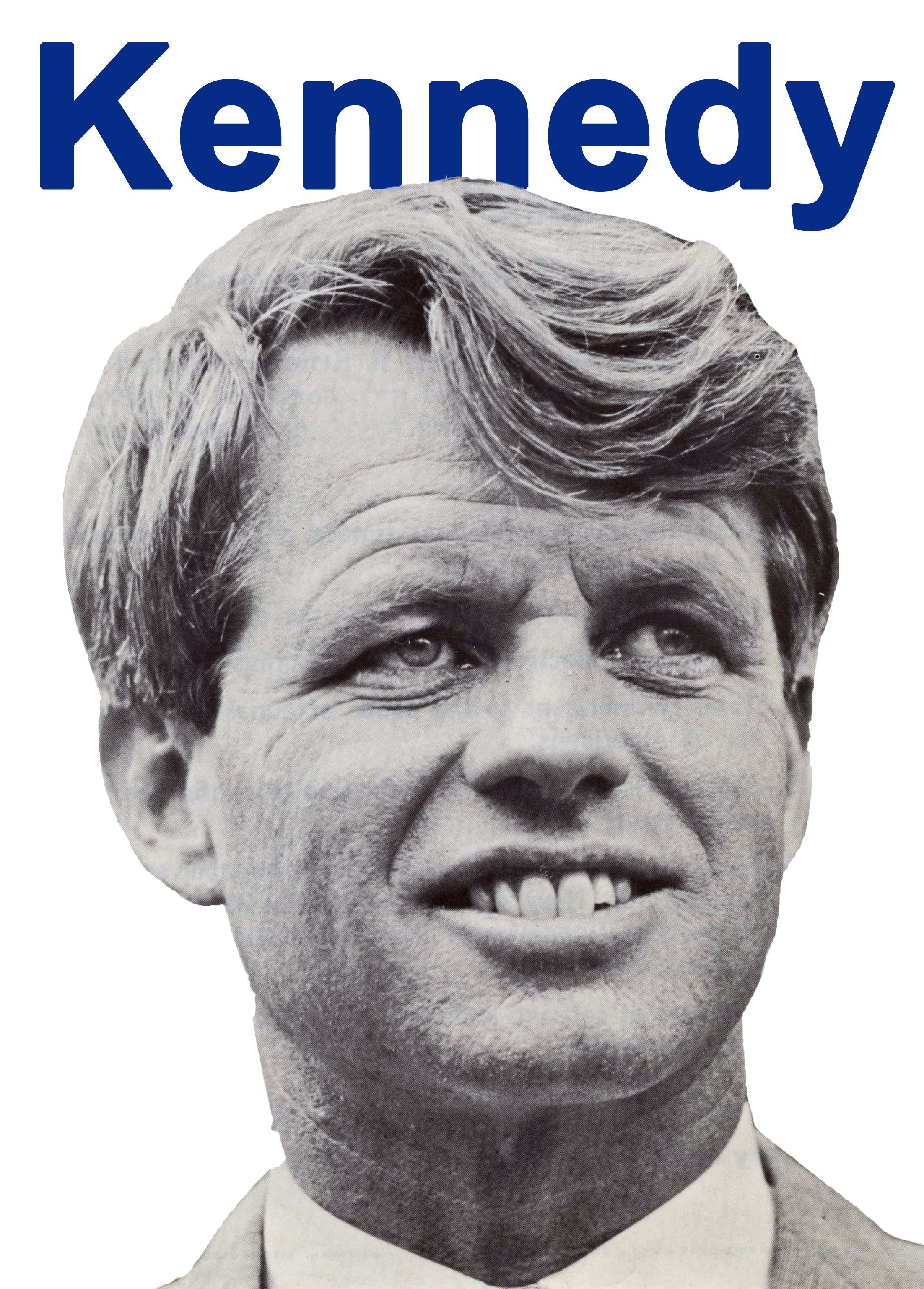

Robert F. Kennedy's Bid For The Presidency on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign began on March 16, 1968, when

The Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign began on March 16, 1968, when

Kennedy was a late entry in making a

Kennedy was a late entry in making a

Accessed May 20, 2018.

"Speech at Ball State University"

(speech, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, 1968-04-04). Retrieved 2012-05-24. In addition, Kennedy enumerated his concerns about poverty and hunger, lawlessness and violence, jobs and economic development, and foreign policy. He emphasized that Americans had a "moral obligation" and should "make an honest effort to understand one another and move forward together." After leaving the stage at Ball State, Kennedy boarded a plane for Indianapolis. When he arrived in Indianapolis he was informed of King's assassination. Later that evening, Kennedy made a brief speech on the assassination of King to a crowd gathered for a political rally at 17th and Broadway—an African American neighborhood near the north side of Indianapolis. He attempted to console the crowd with calls for peace and compassion. After attending King's funeral in

In contrast to Nebraska, the Oregon primary posed several challenges to Kennedy's campaign. His campaign organization, run by Congresswoman Edith Green, was not strong and his platform emphasizing poverty, hunger, and minority issues did not resonate with Oregon voters. Mills wrote the following about RFK's calls for unity amongst Americans: "As far as Oregonians were concerned, America had not fallen apart." The Kennedy campaign circulated material on McCarthy's record; McCarthy had voted against a minimum wage law and repeal of the poll tax in the

In contrast to Nebraska, the Oregon primary posed several challenges to Kennedy's campaign. His campaign organization, run by Congresswoman Edith Green, was not strong and his platform emphasizing poverty, hunger, and minority issues did not resonate with Oregon voters. Mills wrote the following about RFK's calls for unity amongst Americans: "As far as Oregonians were concerned, America had not fallen apart." The Kennedy campaign circulated material on McCarthy's record; McCarthy had voted against a minimum wage law and repeal of the poll tax in the

Kennedy's body was returned to New York City, where he lay in repose at St. Patrick's Cathedral for several days before the

Kennedy's body was returned to New York City, where he lay in repose at St. Patrick's Cathedral for several days before the

The Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign began on March 16, 1968, when

The Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign began on March 16, 1968, when Robert Francis Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, a ...

, a United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, mounted an unlikely challenge

Challenge may refer to:

* Voter challenging or caging, a method of challenging the registration status of voters

* Euphemism for disability

* Peremptory challenge, a dismissal of potential jurors from jury duty

Places

Geography

*Challenge, C ...

to incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an official, office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seek ...

Democratic United States President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United State ...

Lyndon B. Johnson. Following an upset in the New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

Primary, Johnson announced on March 31 that he would not seek re-election. Kennedy still faced two rival candidates for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination: the leading challenger United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

and Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

. Humphrey had entered the race after Johnson's withdrawal, but Kennedy and McCarthy remained the main challengers to the policies of the Johnson administration. During the spring of 1968, Kennedy campaigned in presidential primary elections throughout the United States. Kennedy's campaign was especially active in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, and Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Kennedy's campaign ended on June 6, 1968 when he was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, following his victory in the California Primary. Had Kennedy been elected, he would have been the first brother of a U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

(John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

) to win the presidency himself.

Announcement

Kennedy was a late entry in making a

Kennedy was a late entry in making a campaign announcement

A campaign announcement is the formal public launch of a political campaign, often delivered in a speech by the candidate at a political rally.

Formal campaign announcements play an important role in United States presidential elections, particu ...

for the primary race in the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 1968. His political advisors had been pressuring him to make a decision, fearing Kennedy was running out of time to announce his candidacy. Although Kennedy and his advisors knew it would not be easy to beat the incumbent president, Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy had not ruled out entering the race. U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy had announced his intention to run against Johnson for the Democratic nomination on November 30, 1967. Following McCarthy's announcement, Kennedy remarked to U.S. Senator George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

that he was, "worried about cGovernand other people making early commitments to cCarthy" Excerpt from ''The Last Campaign: Robert F. Kennedy and the 82 Days that Inspired America'' (New York, Henry Holt, 2008) by Thurston Clark. At a breakfast with reporters at the National Press Club on January 30, 1968, Kennedy once again indicated that he had no plans to run, but a few weeks later he had changed his mind about entering the race.

In early February 1968, after the Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, Kennedy received an anguished letter from writer Pete Hamill

Pete Hamill (born William Peter Hamill; June 24, 1935August 5, 2020) was an American journalist, novelist, essayist and editor. During his career as a New York City journalist, he was described as "the author of columns that sought to capture th ...

, noting that poor people in the Watts area of Los Angeles had hung pictures of Kennedy's brother, President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

, in their homes. Hamill's letter reminded Robert Kennedy that he had an "obligation of staying true to whatever it was that put those pictures on those walls."Thomas, p. 357. There were other factors that influenced Kennedy's decision to enter the presidential primary race. On February 29, 1968, the Kerner Commission issued a report on the racial unrest that had affected American cities during the previous summer. The Kerner Commission blamed "white racism" for the violence, but its findings were largely dismissed by the Johnson administration. Concerned about President Johnson's policies and actions, Kennedy asked his advisor, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a spe ...

: "How can we possibly survive five more years of Lyndon Johnson?" Disagreement amongst Kennedy's friends, political advisors, and family members further complicated his decision to launch a primary challenge against the incumbent Johnson. Kennedy's wife Ethel supported the idea, but his brother Ted had been opposed to the candidacy. Ted did lend his support once Kennedy entered the race.

By late February or early March 1968, Kennedy had finally made the decision to enter the race for president. On March 10, Kennedy traveled to California, to meet with civil rights activist César Chávez, at the end of a 25-day hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

. En route to California, Kennedy told his aide, Peter Edelman, that he had decided to run and had to "figure out how to get McCarthy out of it." The weekend before the New Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest (the first being the Iowa caucuses) held in the United States every four years as part of the process of choosi ...

, Kennedy told several aides that he would run if he could persuade little-known Senator Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

to withdraw from the presidential race. Kennedy agreed to McCarthy's request to delay an announcement of his intentions until after the New Hampshire primary. On March 12, when Johnson won an astonishingly narrow victory in the New Hampshire primary against McCarthy, who polled 42 percent of the vote, Kennedy knew it would be unlikely that the Minnesota senator would agree to withdraw. He moved forward with his plans to announce his candidacy.

On March 16, Kennedy declared, "I am today announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United States. I do not run for the presidency merely to oppose any man, but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I'm obliged to do all I can." Kennedy made this announcement from the same spot in the Senate Caucus Room where John F. Kennedy had announced his presidential candidacy in January 1960. McCarthy supporters angrily denounced Kennedy as an opportunist. With Kennedy joining the race, liberal Democrats thought that votes among supporters of the anti-war movement would now be split between McCarthy and Kennedy.

On March 31, President Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

stunned the nation by dropping out of the presidential race. He withdrew from the election during a televised speech, where he also announced a partial halt to the bombing of Vietnam and proposed peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

, long a champion of labor unions and civil rights, entered the race on April 27, with support from the party "establishment"—including the Democratic members of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

, mayors, governors, and labor unions. Although he was a write-in candidate in some of the contests, Humphrey had announced his candidacy too late to be a formal candidate in most of the primaries. Despite late entry into the primary race, Humphrey had the support of the president and many Democratic insiders, which gave him a better chance at gaining convention delegates in the non-primary states. In contrast, Kennedy, like his brother before him, had planned to win the nomination through popular support in the primaries. Because Democratic party leaders would influence delegate selection and convention votes, Kennedy's strategy was to influence the decision-makers with crucial wins in the primary elections. This strategy had worked for John F. Kennedy in 1960, when he beat Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

in the West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

democratic primary.

Kennedy delivered his first campaign speech on March 18 at Kansas State University

Kansas State University (KSU, Kansas State, or K-State) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Manhattan, Kansas, United States. It was opened as the state's land-grant college in 1863 and was the first public instit ...

, where he had previously agreed to give a lecture honoring former Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

governor and Republican Alfred Landon. At Kansas State, Kennedy drew a "record-setting crowd of 14,500 students" for his Landon Lecture. In his speech, Kennedy apologized for early mistakes and attacked President Johnson's Vietnam policy saying, "I was involved in many of the early decisions on Vietnam, decisions which helped set us on our present path." He further acknowledged that "past error is not excuse for its own perpetration." Later that day at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

Kennedy spoke to an audience of 19,000—one of the largest in the university's history. During that speech he said, "I don't think that we have to shoot each other, to beat each other, to curse each other and criticize each other, I think that we can do better in this country. And that is why I run for President of the United States." From Kansas, Kennedy went on to campaign in the Democratic primaries in Indiana, Washington, DC, Nebraska, Oregon, South Dakota, and California.

Policy positions

Kennedy's political platform emphasized racial equality,economic justice

Justice in economics is a subcategory of welfare economics. It is a "set of moral and ethical principles for building economic institutions". Economic justice aims to create opportunities for every person to have a dignified, productive and creativ ...

, non-aggression in foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

, decentralization

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group.

Conce ...

of power and social improvement. A crucial element of his campaign was youth engagement. Kennedy identified America's youth with the future of a reinvigorated American society based on partnership and social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within a specific society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and ...

.

Kennedy's policy objectives were not popular with the business world, where he was viewed as a fiscal liability. Businesses were opposed to the tax increases that would be necessary to fund Kennedy's proposed social programs. During a speech given at the Indiana University Medical School, Kennedy was asked, "Where are we going to get the money to pay for all these new programs you're proposing?" Kennedy replied to the medical students, who were poised to enter lucrative careers, "From you."

Vietnam War

Kennedy did not support an immediate withdrawal of U.S. military personnel from Vietnam or an immediate end to the war. He sought to end the conflict by strengthening the South Vietnamese military and reducing corruption within the South Vietnamese government. He supported a peace settlement between North and South Vietnam.Job opportunities and welfare reform

Kennedy argued that increased government cooperation with private enterprise would reduce housing and employment woes in the United States. He also argued that the focus of welfare spending should be shifted more towards improving credit and income for farmers.Law and order

In 1968, Kennedy expressed his strong willingness to support a bill that was under consideration for the abolition of the death penalty. He argued that rising crime rates could be countered with more job and educational opportunities.Robert F. Kennedy 1968 for President Campaign BrochureAccessed May 20, 2018.

Gun control

Kennedy supported laws that would reduce casual firearm purchases. He said he believed in keeping firearms away from "people who have no business" with them—specifying criminals, individuals with mental health issues, and minors as classes of persons who should be prevented from purchasing firearms.Tax reform

Kennedy argued for legislation, which would reform flagrant tax loopholes.Primary campaign

In 1968, Kennedy was successful in four state primaries:Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

, and California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

; as well as Washington D.C. McCarthy won six state primaries: Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Kennedy's native state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. Of the state primaries in which they campaigned directly against one another, Kennedy won three (Indiana, Nebraska, and California) while McCarthy was only successful in one (Oregon).

Opinion polling

A Gallup poll conducted in the fall of 1965 showed 72% of respondents believed RFK wanted to become the president, and 40% of independents and 56% of Democrats stated their support for a possible bid. Harris and Gallup polls released in August 1966 showed RFK being favored over President Johnson for the nomination by 2% among Democrats and 14% by independents. A late March Gallup poll released shortly before RFK's entry into the primary showed him leading President Johnson by three points at 44% to 41%. A poll released in the early part of April featured Kennedy with a 26-point lead over McCarthy in the Indiana primary, at 46% to 19%.Richardson, pp. 87–89. Another April poll in Indiana, the Oliver Quayle survey, showed Kennedy with a three-to-one lead over McCarthy and the state's governorRoger D. Branigin

Roger Douglas Branigin (July 26, 1902 – November 19, 1975) was an American politician who was the List of governors of Indiana, 42nd governor of Indiana, serving from January 11, 1965, to January 13, 1969. A World War II veteran and well-kno ...

; Schmitt noted the poll featured a large portion of respondents refuting the label that RFK was not trustworthy along with being "too tough and ruthless."Schmitt, pp. 210–211. An April 28 Gallup poll showed Kennedy at 28% support by Democratic voters, Humphrey behind by three points and McCarthy ahead by five. A May 26 Associated Press poll showed RFK behind Humphrey among Pennsylvania national convention delegates, 1 to 27. A June 2 Gallup poll showed Kennedy at 19% support among Democratic county chairmen, Humphrey at 67% and McCarthy at 6%. A June 3 poll showed Kennedy leading McCarthy by nine points in the California primary, at 39% to 30%. The following day, CBS polls showed Kennedy leading McCarthy by seven points.

Indiana primary

On March 27, 1968, Kennedy announced his intention to run against McCarthy in the Indiana primary. His aides told him that a race in Indiana would be an extremely tight race and advised him against it. Despite the concerns of his advisors, Kennedy traveled toIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

the following day and filed to run in the Indiana primary. At the Indiana Statehouse, Kennedy told a cheering crowd that the state was important to his campaign: "If we can win in Indiana, we can win in every other state, and win when we go to the convention in August."

On April 4, 1968, Kennedy made his first campaign stop in Indiana at the University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main campu ...

in South Bend, followed by a speech at Ball State University

Ball State University (Ball State, State or BSU) is a public university, public research university in Muncie, Indiana. It has two satellite facilities in Fishers, Indiana, Fishers and Indianapolis.

On July 25, 1917, the Ball brothers, indust ...

in Muncie. In his speech at Ball State, Kennedy suggested that the 1968 election would "determine the direction that the United States is going to move" and that the American people should "examine everything. Not take anything for granted."Kennedy, Robert F."Speech at Ball State University"

(speech, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, 1968-04-04). Retrieved 2012-05-24. In addition, Kennedy enumerated his concerns about poverty and hunger, lawlessness and violence, jobs and economic development, and foreign policy. He emphasized that Americans had a "moral obligation" and should "make an honest effort to understand one another and move forward together." After leaving the stage at Ball State, Kennedy boarded a plane for Indianapolis. When he arrived in Indianapolis he was informed of King's assassination. Later that evening, Kennedy made a brief speech on the assassination of King to a crowd gathered for a political rally at 17th and Broadway—an African American neighborhood near the north side of Indianapolis. He attempted to console the crowd with calls for peace and compassion. After attending King's funeral in

Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Kennedy turned his attention back to the primary campaign. He drew huge crowds at campaign stops across the country.Thomas, p. 369. Kennedy's Indiana campaign resumed on April 10.

Kennedy's campaign advisor John Bartlow Martin

John Bartlow Martin (4 August 1915, in Hamilton, Ohio – 3 January 1987, in Highland Park, Illinois) was an American diplomat, author of 15 books, ambassador, and speechwriter and confidant to many Democratic politicians including Adlai Stevens ...

urged the candidate to speak out against violence and rioting, emphasize his "law enforcement experience" as former U.S. Attorney General, and promote the idea that the federal government and the private sector should work together to solve domestic issues. Martin also urged Kennedy to speak out on the war in Vietnam—support for the cessation of hostilities and reallocating war funds to domestic programs were ideas which "always got applause." To appeal to Indiana's more-conservative voters, Kennedy "toned down his rhetoric" as well.

RFK delivered a speech before the Indianapolis real estate board on May 2, advocating for reliance on private enterprise instead of the federal government. During this speech, Kennedy argued that the national economy would be "restored" by the Vietnam War's conclusion.

In the days before the Indiana primary, a battle ensued between Kennedy, McCarthy, and Indiana Governor

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government ...

Roger D. Branigin

Roger Douglas Branigin (July 26, 1902 – November 19, 1975) was an American politician who was the List of governors of Indiana, 42nd governor of Indiana, serving from January 11, 1965, to January 13, 1969. A World War II veteran and well-kno ...

. Branigin was a "favorite son candidate" and stand-in for LBJ. He has been described as a "formidable foe who had enormous power over the distribution of the approximately seven thousand patronage jobs in the state." Branigan campaigned in nearly all of the state's 92 counties, while McCarthy's campaign strategy concentrated on Indiana's rural areas and small towns. According to Kennedy's advisor, Martin, the campaign gained momentum with Kennedy's visits to central and southern Indiana on April 22 and 23, which included a memorable whistle-stop railroad trip aboard the Wabash Cannonball.

The Indiana primary was held on May 7: Kennedy won with 42 percent of the vote; Branigan was second with 31 percent of the vote; and McCarthy, earning 27 percent, came in third. With this victory in Indiana, Kennedy's campaign gained momentum going into the Nebraska primary.

Nebraska and Oregon primaries

Campaigning vigorously in Nebraska, Kennedy hoped for a big win to give him momentum going into the California primary, in which McCarthy held a strong presence. While McCarthy made only one visit to Nebraska, Kennedy made numerous appearances. It was during this primary that Kennedy began enjoying himself as he was "open and uncomplicated". Kennedy's advisors had been worried about his chances in Nebraska, given RFK's lack of experience with the issues of ranching and agriculture—subjects of high importance to Nebraskans—and the short amount of time to campaign in the state after the Indiana primary. RFK won the Nebraska primary on May 14, with 51.4 percent of the vote to McCarthy's 31 percent.Thomas, p. 377. Kennedy won 24 of the 25 counties that he visited ahead of the vote; of those, Mills noted that the sole county he lost harbored theUniversity of Nebraska

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

, where a plurality of students favored McCarthy, and that RFK had been defeated by "precisely two votes." After the results, Kennedy declared that he and McCarthy, both anti-war candidates, had collectively managed to earn over 80 percent of the vote. He described this as "a smashing repudiation" of the Johnson-Humphrey administration.

In contrast to Nebraska, the Oregon primary posed several challenges to Kennedy's campaign. His campaign organization, run by Congresswoman Edith Green, was not strong and his platform emphasizing poverty, hunger, and minority issues did not resonate with Oregon voters. Mills wrote the following about RFK's calls for unity amongst Americans: "As far as Oregonians were concerned, America had not fallen apart." The Kennedy campaign circulated material on McCarthy's record; McCarthy had voted against a minimum wage law and repeal of the poll tax in the

In contrast to Nebraska, the Oregon primary posed several challenges to Kennedy's campaign. His campaign organization, run by Congresswoman Edith Green, was not strong and his platform emphasizing poverty, hunger, and minority issues did not resonate with Oregon voters. Mills wrote the following about RFK's calls for unity amongst Americans: "As far as Oregonians were concerned, America had not fallen apart." The Kennedy campaign circulated material on McCarthy's record; McCarthy had voted against a minimum wage law and repeal of the poll tax in the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

. The McCarthy campaign responded with charges that Kennedy illegally taped Martin Luther King, Jr. as United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

. Kennedy admitted these mentions of McCarthy's record did not bother his supporters.

Ten days ahead of the primary, RFK recognized the uphill battle he faced in winning the primary: "This state is like one giant suburb. I appeal best to people who have problems." During a speech he gave in California, Kennedy said, "I think that if I get beaten in any primary, I am not a very viable candidate." The comment further intensified the importance of the Oregon primary.Gould, p. 73. Kennedy realized that losing the Oregon primary would pose a risk to his credibility and began what Dary G. Richardson dubbed an "Olympian-like pace". He campaigned for sixteen hours a day; in the weeks before the election, his campaign canvased 50,000 homes.

On May 26, RFK was campaigning in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, accompanied by his wife Ethel and astronaut John Glenn

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American Marine Corps aviator, engineer, astronaut, businessman, and politician. He was the third American in space, and the first American to orbit the Earth, circling ...

. McCarthy was also campaigning in Portland and briefly encountered RFK's motorcade in Washington Park; Kennedy's campaign aides decided to hold his event in a different location. The following day, a spokesman for the RFK campaign accused the McCarthy and Humphrey campaigns of banding together against Kennedy. On May 28, McCarthy won the Oregon primary with 44.7 percent; Kennedy received 38.8 percent of votes. After Kennedy's loss was confirmed, RFK sent a congratulatory message to McCarthy in which he asserted that he would remain in the race. Larry Tye believes the defeat in Oregon had two effects: First, it proved to RFK that he needed to take risks in his campaigning. Second, the defeat convinced voters that Kennedy was vulnerable to electoral defeat.

After the loss in Oregon, Kennedy's campaign moved on to California.

California, South Dakota, and New Jersey primaries

After victories in Nebraska and Indiana, Kennedy hoped to take the California and South Dakota primaries on June 4. California was "the perfect place for Kennedy to demonstrate his voter-appeal."Dooley, p. 130. McCarthy's California campaign was well-funded and organized. For Kennedy, a defeat could have ended his hopes of securing the nomination. Kennedy was the weakest candidate in the South Dakota primary; McCarthy was a Senator in neighboring Minnesota and Humphrey had been raised in South Dakota. On June 1, during the final days of the California campaign, Kennedy and McCarthy met for a televised debate. Kennedy had hopes of denting McCarthy's strength in California, but the debate proved to be "indecisive and disappointing." After the debate, undecided voters favored Kennedy to McCarthy 2 to 1, the first time in the primary that gains in undecided voters were found to mostly go to RFK.Mills, p. 443. On June 3, in whatArthur Schlesinger, Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a spe ...

dubbed a "final dash around the state", RFK traveled to San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Long Beach. RFK told Theodore H. White

Theodore Harold White (, May 6, 1915 – May 15, 1986) was an American political journalist and historian, known for his reporting from China during World War II and the ''Making of the President'' series.

White started his career reporting for ...

on June 4 that he could sway Democratic Party leaders with wins in both California and South Dakota.Clarke, p. 265. Kennedy won the South Dakota primary by a wide margin, beating McCarthy, 50 percent to 20 percent of the vote. Kennedy won in California with 46 percent of the vote to McCarthy's 42 percent—this was a crucial defeat to McCarthy's campaign and the biggest prize in the nominating process. Under the plurality voting system

Plurality voting refers to electoral systems in which a candidate, or candidates, who poll more than any other counterpart (that is, receive a plurality), are elected. In systems based on single-member districts, it elects just one member per ...

, Kennedy, despite having received only a plurality of the vote, was awarded all of the state's delegates to the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

. Around midnight on June 5, Kennedy addressed supporters at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, confidently promising to heal the many divisions within the country.

Assassination

After addressing his supporters during the early morning hours of June 5, in a ballroom at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Kennedy left the ballroom through a service area to greet kitchen workers. In a crowded kitchen passageway, Sirhan Sirhan, a 24-year-old Palestinian-born Jordanian, opened fire with a.22 caliber .22 caliber, or 5.6 mm caliber, refers to a common firearms bore diameter of 0.22 inch (5.6 mm).

Cartridges in this caliber include the very widely used .22 Long Rifle and .223 Remington / 5.56×45mm NATO.

.22 inch is also a popular ...

revolver

A revolver (also called a wheel gun) is a repeating handgun that has at least one barrel and uses a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold up to six roun ...

and mortally wounded Kennedy. Following the shooting, Kennedy was rushed to Central Receiving Hospital and then transferred to The Good Samaritan Hospital

Good Samaritan Hospital or Good Samaritan Medical Center may refer to:

India

*Good Samaritan Hospital (Panamattom), Koprakalam, Panamattom, Kerala

*Good Samaritan Centre, Mutholath Nagar, Cherpunkal, Kottyam, Kerala

United States

*Banner - Univer ...

, where he died early in the morning on June 6.

Kennedy's body was returned to New York City, where he lay in repose at St. Patrick's Cathedral for several days before the

Kennedy's body was returned to New York City, where he lay in repose at St. Patrick's Cathedral for several days before the Requiem Mass

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

was held there on June 8. His younger brother, U.S. Senator Edward "Ted" Kennedy, eulogized him with the words: "My brother need not be idealized or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it." Kennedy concluded the eulogy by paraphrasing George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, "As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: 'Some men see things as they are and say why? I dream things that never were and say why not?' " Later that day, a funeral train carried Kennedy's body from New York to Washington, D.C., where he was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

.

Relationships with groups and people

Black communities

Kennedy had been a supporter of theCivil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. During the campaign, there were signs in black neighborhoods that read "Kennedy white but alright / The one before, he opened the door." In the Indiana primary, RFK secured 86% of the black vote. His performance was strongest in cities with the largest black populations. Richardson noted that Kennedy was appealing to low-earning black voters. Kennedy had received support from black people by "an overwhelming margin". Support amongst black voters was one of the key factors in Kennedy's victory in Indiana, where he gave a notable speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Indianapolis days before the primary took place. Samuel Lubell

Samuel Lubell (November 3, 1911 – August 16, 1987), born Samuel Lubelsky, was an American public opinion pollster, journalist, and author who successfully predicted election outcomes using door-to-door voter interviews. He published six books ...

argued that the victory was partially inspired by RFK's support for corporate attempts to hire blacks; he wrote that Kennedy had largely won "the Negro wards". However, Indianapolis Star journalist Will Higgins noted that Kennedy got a boost from the King assassination speech, which, unlike many other American cities, aided Indianapolis in being spared of riots. Higgins also noted that the crowd which Kennedy spoke with that evening was estimated to be only 2,500 people.

In the Nebraska primary, Kennedy ended his campaigning in the state with a speech in a black neighborhood in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

. While a late May poll showed that only 40% of overall respondents believed RFK embodied "many of the same outstanding qualities" of the late President Kennedy, 94% of black respondents agreed with the comparison.Cohen, p. 129. When McCarthy revealed that Kennedy had agreed to limited surveillance of Dr. King back in 1963, blacks in California considered switching their support to McCarthy. In Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

, Kennedy met with Black Panthers

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxism-Leninism, Marxist-Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. New ...

amid other minority activists in a midnight session days before the California primary concluded. When he was shouted at, Kennedy prevented a black aide from intervening: "They need to tell people off. They need to tell me off." RFK won 90% of the black vote in the California primary. Larry Tye later said: "By the time of his death in June 1968, Bobby was the most trusted white man in black America." On the other hand, Michael A. Cohen noted that RFK's popularity with blacks had a negative effect on his appeal to the remainder of the electorate: "Rather than create an ''espirit de corps'' between the races, his close relationship to the black community turned many whites off."

Working class whites

Kennedy had broad support among blue-collar white voters during the campaign. Schmitt observed that "It was the allure of Kennedy as a bare knuckles advocate for their interests that led some of these same white voters to support the insurgent candidacy of George Wallace in the fall of 1968." An internal memo released during the Indiana primary showed that Kennedy-backing voters had favorable opinions of Wallace. Samuel Lubell, though noting Kennedy's support among blacks, stated that he "had also carried the racially sensitive low-income white workers who come in from rural areas to settle in east Omaha."Farmworkers

Kennedy endeared himself to farmworkers through his support of theDelano grape strike

The Delano grape strike was a labor strike organized by the United Farm Workers, Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a predominantly Filipino and AFL-CIO-sponsored labor organization, against table grape growers in Delano, Califo ...

and subsequent communications with Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez ; ; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged ...

, who told students in California that Kennedy was the candidate for farmworkers. Tye wrote that RFK became a hero to farmworkers by questioning local law enforcement methods. RFK visited Delano during the campaign to display an endorsement for the grape strike, prompting Chavez to convince the United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

to begin voter turnout and registration campaigns. Marshall Ganz

Marshall Ganz (born March 14, 1943) is the Rita T. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Introduced to organizing in Civil Rights Movement, he worked on the s ...

had arranged for Kennedy to speak to farmworkers after his victory speech in the California primary. Roger A. Bruns wrote the following about Kennedy's assassination: "For the country and especially for the farm workers community, the killing of Robert Kennedy was a profoundly tragic loss."

Hispanics

Chavez claimed there were fifty Hispanics supporting the Kennedy campaign for every one that had backed his brother's campaign eight years prior. In the California primary, 95% of voting Hispanics supported RFK and he won 100% in several precincts. By the time of the primary, he had become "the leading candidate among Latinos in California". Hispanic input heavily impacted Kennedy's victory.Lyndon B. Johnson

Even before Kennedy announced his candidacy, Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) was convinced that Kennedy wanted to challenge him. LBJ was convinced that his presidency would be "trapped forever between the two Kennedys" administrations. Jeff Shesol wrote that LBJ took the prospect of a contentious primary seriously, after having underestimated the political skillfulness of JFK in 1960. During a December 19, 1967 press conference, LBJ said the following about what he called the Kennedy-McCarthy movement: "I don't know what the effect of the Kennedy-McCarthy movement is having in the country ...I am not privileged to all of the conversations that have taken place ...I do know of the interest of both of them in the Presidency and the ambition of both of them." Prior to RFK's announcement of his intentions to run, close friend Arthur Schlesinger wrote in a journal that he'd never seen Kennedy "so torn about anything...I think that he cannot bear the thought of consigning the country to four more years of LBJ, without having done something to avert this." Kennedy announced his candidacy after LBJ almost lost the New Hampshire primary. The day after announcing his candidacy, RFK predicted that Johnson would lose the general election if he was the party's nominee, if he continued to "follow the same policies we are following at the moment". Kennedy told reporters during a flight toKansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more ...

: "I didn't want to run for President. But when ohnsonmade it clear the war would go on, and that nothing was going to change, I had no choice." Clarke wrote that Kennedy was conveying he had a moral obligation to do everything in his power to prevent a prolonging of the policies he opposed. In mid-March, during an appearance at Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

, RFK charged LBJ's leadership with leading to the divisiveness of the U.S.: "They are the ones, the President of the United States, President Johnson, they are the ones who divide us." In late March, three days before LBJ announced that he would not be seeking the Democratic Party's nomination, James H. Rowe

James H. Rowe Jr. (June 1, 1909 – June 17, 1984) was an American lawyer and New Dealer who was selected by President Harry Truman to work on the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, commonly known as the Hoov ...

sent LBJ a memorandum charging that RFK's backers had said "the president would not run and that the best course for the Democrats was to 'Stay loose and stay committed.' " A late-March Gallup poll showed RFK defeating President Johnson in a national election.

RFK was at his apartment in the United Nations Plaza the night President Johnson announced his withdrawal from the primary, though unlike his supporters he was not optimistic about the news. He reportedly said, "The joy is premature." Smith observed that Johnson's withdrawal meant Kennedy would have to shift the focus of his critiques from the administration's policies on the Vietnam War. Shesol wrote that Kennedy moved to a praising tone of Johnson, crediting Johnson with fulfillment of "the policies of thirty years" during an April 1 appearance in New Jersey. While in Philadelphia, he called Johnson's withdrawal an "act of leadership and sacrifice".Shesol, pp. 446–447. On April 3, 1968, three days after President Johnson announced that he would not seek the nomination, RFK and the President met at the White House. When asked about his intentions for the primary, LBJ replied: "Stay out of it". Although Johnson's withdrawal from the race meant Vice-President Humphrey would enter, RFK had gained the president's declaration of neutrality. In comments to Henry Ford II

Henry Ford II (September 4, 1917 – September 29, 1987), sometimes known as "Hank the Deuce", was an American businessman in the automotive industry. He was the oldest son of Edsel Ford I and oldest grandson of Henry Ford I. He was president ...

and Gregory Peck

Eldred Gregory Peck (April 5, 1916 – June 12, 2003) was an American actor and one of the most popular film stars from the 1940s to the 1970s. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Peck the 12th-greatest male star of Classic Hollywood ...

, LBJ concluded that RFK won his June debate with McCarthy.

Eugene McCarthy

After the primaries, McCarthy claimed that RFK had promised in November 1967 that he would not run. Prior to entering the race, RFK worried McCarthy lacked a platform, as the latter had rarely spoken about domestic issues. In mid-March,Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

attempted to broker "a political deal" where his brother would remain out of the race, if McCarthy spoke out on domestic problems. McCarthy declined and the refusal propelled Schlesinger's unsuccessful suggestion that RFK endorse McCarthy.Smith, p. 237. The day before RFK announced his entry into the primary, he told reporters Hayne Johnson and Jack Newfield: "I can't be a hypocrite anymore. I just don't believe Gene McCarthy would be a good president. If it had been George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

who had run in New Hampshire, I wouldn't have gotten into it. But what has McCarthy ever done for the ghettos or for the poor?"

The day Kennedy announced his entry into the primary, McCarthy reversed his decision to not enter the Indiana primary; he didn't want to help RFK's chances of winning any primaries. According to Dominic Sandbrook, Kennedy's entry into the primary caused a shift in McCarthy's campaign—McCarthy was forced to further develop his own platform, instead of merely being antagonistic to the Johnson administration's policies. Walter LaFeber believed that animosity between the Kennedy and McCarthy campaigns had grown by the end of March. Following President Johnson's withdrawal from the primary, McCarthy said: "Up to now Bobby was Jack running against Lyndon. Now Bobby has to run against Jack." Mills wrote that Kennedy's focus on providing assistance for the poor and powerless during the Indiana primary was meant to highlight an issue that the McCarthy campaign had neglected. After his Nebraska victory, Kennedy said that McCarthy supporters should support him to prevent the nomination of Humphrey at the Democratic National Convention. McCarthy rebuked RFK's proposals about fixing cities during a late May speech at University of California, Davis

The University of California, Davis (UC Davis, UCD, or Davis) is a public land-grant research university near Davis, California. Named a Public Ivy, it is the northernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California system. The institut ...

.Cohen, p. 123. The McCarthy campaign believed that if RFK did well enough to survive the California primary, it would lead to a fractured Democratic National Convention where McCarthy would be the alternative for those opposed to both RFK and Humphrey. After the California primary, some Kennedy advisors joined the McCarthy campaign with plans for supporting it toward gaining the nomination.Mills, p. 446.

Hubert Humphrey

Two days after RFK announced his candidacy, Vice President Humphrey said that RFK had supported the JFK administration's policies on the Vietnam conflict. Humphrey's office produced a statement from Kennedy, written six years prior, saying the U.S. would win in Vietnam. Kennedy was in Nebraska when Humphrey entered the race on April 27. Kennedy welcomed Humphrey into the race, saying Humphrey's candidacy offered "clear alternatives" between the Johnson administration's policies and those of the primary candidates. LaFeber wrote that Humphrey's entry seemed to be hinged entirely on President Johnson's distaste at the idea of Kennedy being the party's nominee in the general election. RFK took direct aim at Humphrey's "politics of joy" line during his announcement speech while campaigning in Indiana: "It is easy to say this is the politics of happiness—but if you see children starving in the Delta of Mississippi and despair on the Indian reservations, then you know that everybody in America is not satisfied." Humphrey won 18% of write-in votes in the Massachusetts primary; it was seen as a victory over Kennedy's 28% vote total because Kennedy's Massachusetts campaign organization was significantly stronger than Humphrey's. The morning after his Oregon loss, Kennedy hosted a Los Angeles airport press conference in which he critiqued Humphrey for what he called an inability "to present his views to the voters of a single state." Kennedy also emphasized that there would be no anti-war Presidential candidate, if Humphrey were the Democratic candidate in the general election against former Vice President Nixon. After winning the California primary, RFK said that he intended to follow Humphrey "all over the country" in pursuit of the nomination. Reflecting on RFK's assassination, Humphrey said: "I was doing everything I could to get the nomination, but God knows I didn't want it that way." Humphrey went on to become the Democratic Party's nominee in the general election.Richard J. Daley

Shortly before entering the race, on February 8, 1968, RFK met with Richard J. Daley about the chances of usurping the nomination from the incumbent President Johnson. RFK wanted Daley to use his influence to sway delegates and the Democratic National Convention in his favor toward nomination. Daley stated that he would remain committed to Johnson. Savage wrote that Daley was worried about an RFK Presidency because he had, as Attorney General, prosecuted Democratic machine politicians in several states.Richard Nixon

After President Johnson withdrew from the primary, Nixon commented that RFK seemed favored for the nomination. WhenRichard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

heard that RFK had announced his candidacy, Nixon reportedly said, "We've just seen some very terrible forces unleashed. Something bad is going to come out of this."Clarke, pp. 22–24. However, Nixon was relieved by RFK's entry into the Democratic primary—he believed the divisions created by RFK's candidacy would be an advantage for Republicans. In April, Nixon proposed a debate between Kennedy and himself. Nixon, who during his own campaign for the presidency spoke about federal power to the states and economic empowerment for blacks in a late May speech, said: "Bobby and I have been sounding pretty much alike." Kennedy tied with Nixon in polls conducted in the latter part of 1967. When Kennedy was announced the winner of the California primary, Nixon told his family: "It sure looks like we'll be going against Bobby."

Kennedy family

Kennedy's wife, Ethel, regularly joined Kennedy when he was campaigning. His brotherTed

TED may refer to:

Economics and finance

* TED spread between U.S. Treasuries and Eurodollar

Education

* ''Türk Eğitim Derneği'', the Turkish Education Association

** TED Ankara College Foundation Schools, Turkey

** Transvaal Education Depa ...

and brother-in-law Steve Smith, were involved in the campaign as informal advisors.Bzdek, p. 133. Ted and his sisters Jean Kennedy Smith

Jean Ann Kennedy Smith (February 20, 1928June 17, 2020) was an American diplomat, activist, humanitarian, and author who served as United States Ambassador to Ireland from 1993 to 1998. She was a member of the Kennedy family, the eighth of nine c ...

and Patricia Kennedy Lawford

Patricia Helen Kennedy Lawford (May 6, 1924 – September 17, 2006) was an American socialite, and the sixth of nine children of Rose and Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. She was a sister of President John F. Kennedy, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and Senator ...

were in the entourage of the Kennedy campaign at the Ambassador Hotel after RFK won the California primary. RFK met with his father Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy (September 6, 1888 – November 18, 1969) was an American businessman, investor, and politician. He is known for his own political prominence as well as that of his children and was the patriarch of the Irish-American Ken ...

ahead of making the announcement; the elder Kennedy dropped his head "to his chest in regret." Bzdek wrote, "He no longer wished to see three sons as president; he only wished to see the last two alive."

Notes

Bibliography

* * * {{Robert F. Kennedy, state=expanded Robert F. Kennedy 1968 Democratic Party (United States) presidential campaigns