Rimsky-Korsakov Serow Crop on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ.

la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow''.

The BGN/PCGN

Rimsky-Korsakov was born in

Rimsky-Korsakov was born in  Throughout history, members of the family served in Russian government and took various positions as governors and war generals.

Throughout history, members of the family served in Russian government and took various positions as governors and war generals.

N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov. From the Family Letters

– Saint Petersburg: Compositor, 247 pages, pp. 8–9 By a Tsar's decree on May 15, 1677, 18 representatives of the Korsakov family acquired the right to be called the Rimsky-Korsakov family (Russian adjective 'Rimsky' means 'Roman') since the family "had a beginning within the Roman borders", i.e. The Rimsky-Korsakov family had a long line of military and naval service. Nikolai's older brother Voin, 22 years his senior, became a well-known navigator and explorer and had a powerful influence on Nikolai's life.Taruskin, ''Music'', p. 166. He later recalled that his mother played the piano a little, and his father could play a few songs on the piano by ear. Beginning at six, he took piano lessons from local teachers and showed a talent for aural skills,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:27. but he showed a lack of interest, playing, as he later wrote, "badly, carelessly, ... poor at keeping time".

Although he started composing by age 10, Rimsky-Korsakov preferred literature to music. He later wrote that from his reading, and tales of his brother's exploits, he developed a poetic love for the sea "without ever having seen it". This love, with subtle prompting from Voin, encouraged the 12-year-old to join the

The Rimsky-Korsakov family had a long line of military and naval service. Nikolai's older brother Voin, 22 years his senior, became a well-known navigator and explorer and had a powerful influence on Nikolai's life.Taruskin, ''Music'', p. 166. He later recalled that his mother played the piano a little, and his father could play a few songs on the piano by ear. Beginning at six, he took piano lessons from local teachers and showed a talent for aural skills,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:27. but he showed a lack of interest, playing, as he later wrote, "badly, carelessly, ... poor at keeping time".

Although he started composing by age 10, Rimsky-Korsakov preferred literature to music. He later wrote that from his reading, and tales of his brother's exploits, he developed a poetic love for the sea "without ever having seen it". This love, with subtle prompting from Voin, encouraged the 12-year-old to join the  While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh. Voin, now director of the school, sanctioned these lessons because he hoped they would help Nikolai develop social skills and overcome his shyness. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that, while "indifferent" to lessons, he developed a love for music, fostered by visits to the opera and, later, orchestral concerts.

Ulikh perceived Rimsky-Korsakov's musical talent and recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore Canillé). Beginning in late 1859, Rimsky-Korsakov took lessons in piano and composition from Kanille, whom he later credited as the inspiration for devoting his life to composition.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 16. Through Kanille, he was exposed to a great deal of new music, including

While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh. Voin, now director of the school, sanctioned these lessons because he hoped they would help Nikolai develop social skills and overcome his shyness. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that, while "indifferent" to lessons, he developed a love for music, fostered by visits to the opera and, later, orchestral concerts.

Ulikh perceived Rimsky-Korsakov's musical talent and recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore Canillé). Beginning in late 1859, Rimsky-Korsakov took lessons in piano and composition from Kanille, whom he later credited as the inspiration for devoting his life to composition.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 16. Through Kanille, he was exposed to a great deal of new music, including  Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev prompted him to enrich himself in history, literature and criticism. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continue working on it despite his lack of formal musical training.

By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month cruise aboard the

Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev prompted him to enrich himself in history, literature and criticism. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continue working on it despite his lack of formal musical training.

By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month cruise aboard the

Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that "Balakirev had no difficulty in getting along with me. At his suggestion I most readily rewrote the symphonic movements composed by me and brought them to completion with the help of his advice and improvisations". Though Rimsky-Korsakov later found Balakirev's influence stifling, and broke free from it,Maes, p. 44. this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser. Under Balakirev's mentoring, Rimsky-Korsakov turned to other compositions. He began a symphony in B minor, but felt it too closely followed

Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that "Balakirev had no difficulty in getting along with me. At his suggestion I most readily rewrote the symphonic movements composed by me and brought them to completion with the help of his advice and improvisations". Though Rimsky-Korsakov later found Balakirev's influence stifling, and broke free from it,Maes, p. 44. this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser. Under Balakirev's mentoring, Rimsky-Korsakov turned to other compositions. He began a symphony in B minor, but felt it too closely followed

Rimsky-Korsakov explained in his memoirs that

Rimsky-Korsakov explained in his memoirs that  Professorship brought Rimsky-Korsakov financial security,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:28 which encouraged him to settle down and to start a family. In December 1871 he proposed to

Professorship brought Rimsky-Korsakov financial security,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:28 which encouraged him to settle down and to start a family. In December 1871 he proposed to  In early 1873, the navy created the civilian post of Inspector of Naval Bands, with a rank of Collegiate Assessor, and appointed Rimsky-Korsakov. This kept him on the navy payroll and listed on the roster of the Chancellery of the Navy Department but allowed him to resign his commission. The composer commented, "I parted with delight with both my military status and my officer's uniform", he later wrote. "Henceforth I was a musician officially and incontestably." As Inspector, Rimsky-Korsakov applied himself with zeal to his duties. He visited naval bands throughout Russia, supervised the bandmasters and their appointments, reviewed the bands' repertoire, and inspected the quality of their instruments. He wrote a study program for a complement of music students who held navy fellowships at the Conservatory, and acted as an intermediary between the Conservatory and the navy. He also indulged in a long-standing desire to familiarize himself with the construction and playing technique of orchestral instruments. These studies prompted him to write a textbook on orchestration.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 136. He used the privileges of rank to exercise and expand upon his knowledge. He discussed arrangements of musical works for military band with bandmasters, encouraged and reviewed their efforts, held concerts at which he could hear these pieces, and orchestrated original works, and works by other composers, for military bands.

In March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties. He worked under Balakirev in the

In early 1873, the navy created the civilian post of Inspector of Naval Bands, with a rank of Collegiate Assessor, and appointed Rimsky-Korsakov. This kept him on the navy payroll and listed on the roster of the Chancellery of the Navy Department but allowed him to resign his commission. The composer commented, "I parted with delight with both my military status and my officer's uniform", he later wrote. "Henceforth I was a musician officially and incontestably." As Inspector, Rimsky-Korsakov applied himself with zeal to his duties. He visited naval bands throughout Russia, supervised the bandmasters and their appointments, reviewed the bands' repertoire, and inspected the quality of their instruments. He wrote a study program for a complement of music students who held navy fellowships at the Conservatory, and acted as an intermediary between the Conservatory and the navy. He also indulged in a long-standing desire to familiarize himself with the construction and playing technique of orchestral instruments. These studies prompted him to write a textbook on orchestration.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 136. He used the privileges of rank to exercise and expand upon his knowledge. He discussed arrangements of musical works for military band with bandmasters, encouraged and reviewed their efforts, held concerts at which he could hear these pieces, and orchestrated original works, and works by other composers, for military bands.

In March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties. He worked under Balakirev in the

Two projects helped Rimsky-Korsakov focus on less academic music-making. The first was the creation of two folk song collections in 1874. Rimsky-Korsakov transcribed 40 Russian songs for voice and piano from performances by folk singer Tvorty Filippov, who approached him at Balakirev's suggestion. This collection was followed by a second containing 100 songs, supplied by friends and servants, or taken from rare and out-of-print collections.Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:402. Rimsky-Korsakov later credited this work as a great influence on him as a composer;Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 166. it also supplied a vast amount of musical material from which he could draw for future projects, either by direct quotation or as models for composing fakeloric passages. The second project was the editing of orchestral scores by pioneer Russian composer Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) in collaboration with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov. Glinka's sister, Lyudmila Ivanovna Shestakova, wanted to preserve her brother's musical legacy in print, and paid the costs of the project from her own pocket. No similar project had been attempted before in Russian music, and guidelines for scholarly musical editing had to be established and agreed. While Balakirev favored making changes in Glinka's music to "correct" what he saw as compositional flaws, Rimsky-Korsakov favored a less intrusive approach. Eventually, Rimsky-Korsakov prevailed. "Work on Glinka's scores was an unexpected schooling for me", he later wrote. "Even before this I had known and worshipped his operas; but as editor of the scores in print I had to go through Glinka's style and instrumentation to their last little note ... And this was a beneficent discipline for me, leading me as it did to the path of modern music, after my vicissitudes with counterpoint and strict style".

In mid-1877, Rimsky-Korsakov thought increasingly about the short story ''

Two projects helped Rimsky-Korsakov focus on less academic music-making. The first was the creation of two folk song collections in 1874. Rimsky-Korsakov transcribed 40 Russian songs for voice and piano from performances by folk singer Tvorty Filippov, who approached him at Balakirev's suggestion. This collection was followed by a second containing 100 songs, supplied by friends and servants, or taken from rare and out-of-print collections.Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:402. Rimsky-Korsakov later credited this work as a great influence on him as a composer;Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 166. it also supplied a vast amount of musical material from which he could draw for future projects, either by direct quotation or as models for composing fakeloric passages. The second project was the editing of orchestral scores by pioneer Russian composer Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) in collaboration with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov. Glinka's sister, Lyudmila Ivanovna Shestakova, wanted to preserve her brother's musical legacy in print, and paid the costs of the project from her own pocket. No similar project had been attempted before in Russian music, and guidelines for scholarly musical editing had to be established and agreed. While Balakirev favored making changes in Glinka's music to "correct" what he saw as compositional flaws, Rimsky-Korsakov favored a less intrusive approach. Eventually, Rimsky-Korsakov prevailed. "Work on Glinka's scores was an unexpected schooling for me", he later wrote. "Even before this I had known and worshipped his operas; but as editor of the scores in print I had to go through Glinka's style and instrumentation to their last little note ... And this was a beneficent discipline for me, leading me as it did to the path of modern music, after my vicissitudes with counterpoint and strict style".

In mid-1877, Rimsky-Korsakov thought increasingly about the short story ''

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that he became acquainted with budding music patron

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that he became acquainted with budding music patron

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts. One of them included the first complete performance of his First Symphony, subtitled ''Winter Daydreams'', in its final version. Another concert featured the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony in its revised version.Brown, ''Final Years'', 91. Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky corresponded considerably before the visit and spent a lot of time together, along with Glazunov and Lyadov.Brown, ''Final Years'', p. 90. Though Tchaikovsky had been a regular visitor to the Rimsky-Korsakov home since 1876, and had at one point offered to arrange Rimsky-Korsakov's appointment as director of the Moscow Conservatory,Taruskin, ''Stravinsky'', p. 31. this was the beginning of closer relations between the two. Within a couple of years, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, Tchaikovsky's visits became more frequent.

During these visits and especially in public, Rimsky-Korsakov wore a mask of geniality. Privately, he found the situation emotionally complex, and confessed his fears to his friend, the Moscow critic Semyon Kruglikov. Memories persisted of the tension between Tchaikovsky and The Five over the differences in their musical philosophies—tension acute enough for Tchaikovsky's brother Modest to liken their relations at that time to "those between two friendly neighboring states ... cautiously prepared to meet on common ground, but jealously guarding their separate interests". Rimsky-Korsakov observed, not without annoyance, how Tchaikovsky became increasingly popular among Rimsky-Korsakov's followers. This personal jealousy was compounded by a professional one, as Tchaikovsky's music became increasingly popular among the composers of the Belyayev circle, and remained on the whole more famous than his own. Even so, when Tchaikovsky attended Rimsky-Korsakov's

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts. One of them included the first complete performance of his First Symphony, subtitled ''Winter Daydreams'', in its final version. Another concert featured the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony in its revised version.Brown, ''Final Years'', 91. Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky corresponded considerably before the visit and spent a lot of time together, along with Glazunov and Lyadov.Brown, ''Final Years'', p. 90. Though Tchaikovsky had been a regular visitor to the Rimsky-Korsakov home since 1876, and had at one point offered to arrange Rimsky-Korsakov's appointment as director of the Moscow Conservatory,Taruskin, ''Stravinsky'', p. 31. this was the beginning of closer relations between the two. Within a couple of years, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, Tchaikovsky's visits became more frequent.

During these visits and especially in public, Rimsky-Korsakov wore a mask of geniality. Privately, he found the situation emotionally complex, and confessed his fears to his friend, the Moscow critic Semyon Kruglikov. Memories persisted of the tension between Tchaikovsky and The Five over the differences in their musical philosophies—tension acute enough for Tchaikovsky's brother Modest to liken their relations at that time to "those between two friendly neighboring states ... cautiously prepared to meet on common ground, but jealously guarding their separate interests". Rimsky-Korsakov observed, not without annoyance, how Tchaikovsky became increasingly popular among Rimsky-Korsakov's followers. This personal jealousy was compounded by a professional one, as Tchaikovsky's music became increasingly popular among the composers of the Belyayev circle, and remained on the whole more famous than his own. Even so, when Tchaikovsky attended Rimsky-Korsakov's

In March 1889, Angelo Neumann's traveling "

In March 1889, Angelo Neumann's traveling "

A lifelong liberal politically,Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:405. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that he felt someone had to protect the rights of the students to demonstrate, especially as disputes and wrangling between students and authorities were becoming increasingly violent. In an open letter, he sided with the students against what he saw as unwarranted interference by Conservatory leadership and the Russian Musical Society. A second letter, this time signed by a number of faculty including Rimsky-Korsakov, demanded the resignation of the head of the Conservatory. Partly as a result of these two letters he wrote, approximately 100 Conservatory students were expelled and he was removed from his professorship.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 412.

Just before the dismissal was enacted, Rimsky-Korsakov received a letter from one of the members of the school directorate, suggesting that he take up the directorship in the interest of calming student unrest. "Probably the member of the Directorate held a minority opinion, but signed the resolution nevertheless," he wrote. "I sent a negative reply." Partly in defiance of his dismissal, Rimsky-Korsakov continued teaching his students from his home.

Not long after Rimsky-Korsakov's dismissal, a student production of his opera ''

A lifelong liberal politically,Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:405. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that he felt someone had to protect the rights of the students to demonstrate, especially as disputes and wrangling between students and authorities were becoming increasingly violent. In an open letter, he sided with the students against what he saw as unwarranted interference by Conservatory leadership and the Russian Musical Society. A second letter, this time signed by a number of faculty including Rimsky-Korsakov, demanded the resignation of the head of the Conservatory. Partly as a result of these two letters he wrote, approximately 100 Conservatory students were expelled and he was removed from his professorship.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 412.

Just before the dismissal was enacted, Rimsky-Korsakov received a letter from one of the members of the school directorate, suggesting that he take up the directorship in the interest of calming student unrest. "Probably the member of the Directorate held a minority opinion, but signed the resolution nevertheless," he wrote. "I sent a negative reply." Partly in defiance of his dismissal, Rimsky-Korsakov continued teaching his students from his home.

Not long after Rimsky-Korsakov's dismissal, a student production of his opera '' In April 1907, Rimsky-Korsakov conducted a pair of concerts in Paris, hosted by impresario

In April 1907, Rimsky-Korsakov conducted a pair of concerts in Paris, hosted by impresario

Rimsky-Korsakov followed the musical ideals espoused by The Five. He employed Orthodox liturgical themes in the ''

Rimsky-Korsakov followed the musical ideals espoused by The Five. He employed Orthodox liturgical themes in the ''

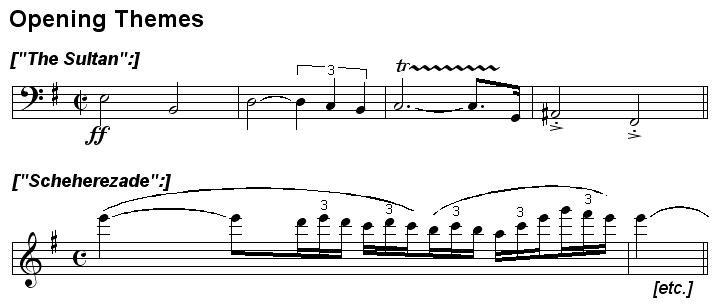

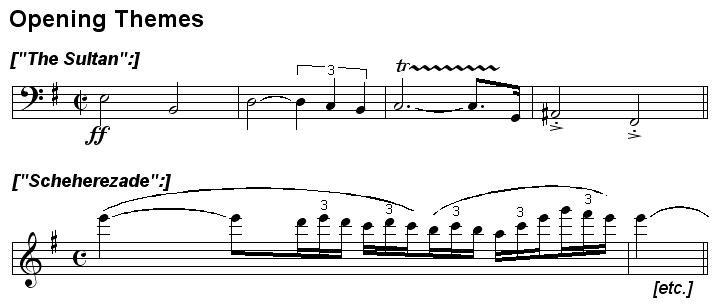

Program music came naturally to Rimsky-Korsakov. To him, "even a folk theme has a program of sorts."Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:409. He composed the majority of his orchestral works in this genre at two periods of his career—at the beginning, with ''Sadko'' and ''Antar'' (also known as his Second Symphony, Op. 9), and in the 1880s, with ''Scheherazade'', ''Capriccio Espagnol'' and the ''Russian Easter Overture''. Despite the gap between these two periods, the composer's overall approach and the way he used his musical themes remained consistent. Both ''Antar'' and ''Scheherazade'' use a robust "Russian" theme to portray the male protagonists (the title character in ''Antar''; the sultan in ''Scheherazade'') and a more sinuous "Eastern" theme for the female ones (the

Program music came naturally to Rimsky-Korsakov. To him, "even a folk theme has a program of sorts."Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:409. He composed the majority of his orchestral works in this genre at two periods of his career—at the beginning, with ''Sadko'' and ''Antar'' (also known as his Second Symphony, Op. 9), and in the 1880s, with ''Scheherazade'', ''Capriccio Espagnol'' and the ''Russian Easter Overture''. Despite the gap between these two periods, the composer's overall approach and the way he used his musical themes remained consistent. Both ''Antar'' and ''Scheherazade'' use a robust "Russian" theme to portray the male protagonists (the title character in ''Antar''; the sultan in ''Scheherazade'') and a more sinuous "Eastern" theme for the female ones (the

One point Stasov omitted purposely, which would have disproved his statement completely, was that at the time he wrote it, Rimsky-Korsakov had been pouring his "book learning" into students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory for over a decade.Taruskin, ''Stravinsky'', 29. Beginning with his three years of self-imposed study, Rimsky-Korsakov had drawn closer to Tchaikovsky and further away from the rest of The Five, while the rest of The Five had drawn back from him and Stasov had branded him a "renegade".

One point Stasov omitted purposely, which would have disproved his statement completely, was that at the time he wrote it, Rimsky-Korsakov had been pouring his "book learning" into students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory for over a decade.Taruskin, ''Stravinsky'', 29. Beginning with his three years of self-imposed study, Rimsky-Korsakov had drawn closer to Tchaikovsky and further away from the rest of The Five, while the rest of The Five had drawn back from him and Stasov had branded him a "renegade".

Musicologist Francis Maes wrote that while Rimsky-Korsakov's efforts are laudable, they are also controversial. It was generally assumed that with ''Prince Igor'', Rimsky-Korsakov edited and orchestrated the existing fragments of the opera while Glazunov composed and added missing parts, including most of the third act and the overture. This was exactly what Rimsky-Korsakov stated in his memoirs. Both Maes and

Musicologist Francis Maes wrote that while Rimsky-Korsakov's efforts are laudable, they are also controversial. It was generally assumed that with ''Prince Igor'', Rimsky-Korsakov edited and orchestrated the existing fragments of the opera while Glazunov composed and added missing parts, including most of the third act and the overture. This was exactly what Rimsky-Korsakov stated in his memoirs. Both Maes and

Abstract.

* Seaman, Gerald :Nikolay Andreevich Rimsky-Korsakov: A Research and Information Guide, Second Edition, Routledge, 2014.

''The Rimsky-Korsakov Home Page''

* * * – full, searchable text with music images, mp3 files, and MusicXML files

''Principles of Orchestration''

full text with "interactive scores"

Rimsky-Korsakov's academic genealogy entry

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai 1844 births 1908 deaths 19th-century classical composers 19th-century male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century Russian male musicians Burials at Tikhvin Cemetery Imperial Russian Navy personnel Male opera composers People from Tikhvin People from Tikhvinsky Uyezd Russian atheists Russian male classical composers Russian music educators Russian music theorists Russian opera composers Russian Romantic composers Saint Petersburg Conservatory academic personnel The Five (composers) Russian nobility 19th-century musicologists

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow''.

The BGN/PCGN

transliteration of Russian

The romanization of the Russian language (the transliteration of Russian text from the Cyrillic script into the Latin script), aside from its primary use for including Russian names and words in text written in a Latin alphabet, is also essential ...

is used for his name here. ALA-LC system: Nikolaĭ Andrevich Rimskiĭ-Korsakov, ISO 9 system: Nikolaj Andreevič Rimskij-Korsakov. (18 March 1844 – 21 June 1908)

was a Russian composer, a member of the group of composers known as The Five. He was a master of orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orc ...

. His best-known orchestral compositions—''Capriccio Espagnol

''Capriccio espagnol'', Op. 34, is the common Western title for a five movement orchestral suite, based on Spanish folk melodies, composed by the Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1887. It received its premiere on 31 October 1887, in St ...

'', the ''Russian Easter Festival Overture

''Russian Easter Festival Overture: Overture on Liturgical Themes'' (russian: Светлый праздник, translit=Svetly prazdnik, translation=Bright festival), Op. 36, also known as the ''Great Russian Easter Overture'', is a concert over ...

'', and the symphonic suite

Suite may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*Suite (music), a set of musical pieces considered as one composition

** Suite (Bach), a list of suites composed by J. S. Bach

** Suite (Cassadó), a mid-1920s composition by Gaspar Cassadó

** ''Suite' ...

''Scheherazade

Scheherazade () is a major female character and the storyteller in the frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the ''One Thousand and One Nights''.

Name

According to modern scholarship, the name ''Scheherazade'' deri ...

''—are staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his 15 operas. ''Scheherazade'' is an example of his frequent use of fairy-tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

and folk subjects.

Rimsky-Korsakov believed in developing a nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

style of classical music, as did his fellow composer Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian: Miliy Alekseyevich Balakirev; ALA-LC system: ''Miliĭ Alekseevich Balakirev''; ISO 9 system: ''Milij Alekseevič Balakir ...

and the critic Vladimir Stasov

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (also Stassov; rus, Влади́мир Васи́льевич Ста́сов; 14 January Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._2_January.html" ;"title="Adoption of ...

. This style employed Russian folk song and lore

Lore may refer to:

* Folklore, acquired knowledge or traditional beliefs

* Oral lore or oral tradition, orally conveyed cultural knowledge and traditions

Places

* Loré, former French commune

* Loré (East Timor), a city and subdistrict in Lau ...

along with exotic harmonic, melodic

A melody (from Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combinat ...

and rhythmic Rhythmic may refer to:

* Related to rhythm

* Rhythmic contemporary, a radio format

* Rhythmic adult contemporary, a radio format

* Rhythmic gymnastics, a form of gymnastics

* Rhythmic (chart)

The Rhythmic chart (also called Rhythmic Airplay, and ...

elements in a practice known as musical orientalism

In art history, literature and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world. These depictions are usually done by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist p ...

, and eschewed traditional Western compositional methods. Rimsky-Korsakov appreciated Western musical techniques after he became a professor of musical composition, harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

, and orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

in 1871. He undertook a rigorous three-year program of self-education and became a master of Western methods, incorporating them alongside the influences of Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, link=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka., mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recogni ...

and fellow members of The Five. Rimsky-Korsakov's techniques of composition and orchestration were further enriched by his exposure to the works of Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

.

For much of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov combined his composition and teaching with a career in the Russian military—first as an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

, then as the civilian Inspector of Naval Bands. He wrote that he developed a passion for the ocean in childhood from reading books and hearing of his older brother's exploits in the navy. This love of the sea may have influenced him to write two of his best-known orchestral works, the musical tableau ''Sadko

Sadko (russian: Садко) is the principal character in a Russian medieval epic ''bylina''. He was an adventurer, merchant, and ''gusli'' musician from Novgorod.

Textual notes

"Sadko" is a version of the tale translated by Arthur Ransome in ...

'' (not to be confused with his later opera of the same name) and ''Scheherazade''. As Inspector of Naval Bands, Rimsky-Korsakov expanded his knowledge of woodwind and brass playing, which enhanced his abilities in orchestration. He passed this knowledge to his students, and also posthumously through a textbook on orchestration that was completed by his son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg

Maximilian Osseyevich Steinberg (Russian Максимилиан Осеевич Штейнберг; – 6 December 1946) was a Russian composer of classical music.

Though once considered the hope of Russian music, Steinberg is far less well known ...

.

Rimsky-Korsakov left a considerable body of original Russian nationalist

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early B ...

compositions. He prepared works by The Five for performance, which brought them into the active classical repertoire (although there is controversy over his editing of the works of Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

), and shaped a generation of younger composers and musicians during his decades as an educator. Rimsky-Korsakov is therefore considered "the main architect" of what the classical-music public considers the "Russian style". His influence on younger composers was especially important, as he served as a transitional figure between the autodidactism

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individua ...

exemplified by Glinka and The Five, and professionally trained composers, who became the norm in Russia by the closing years of the 19th century. While Rimsky-Korsakov's style was based on those of Glinka, Balakirev, Hector Berlioz

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

, Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

and, for a brief period, Wagner, he "transmitted this style directly to two generations of Russian composers" and influenced non-Russian composers including Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Paul Dukas

Paul Abraham Dukas ( or ; 1 October 1865 – 17 May 1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, having abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His b ...

, and Ottorino Respighi

Ottorino Respighi ( , , ; 9 July 187918 April 1936) was an Italian composer, violinist, teacher, and musicologist and one of the leading Italian composers of the early 20th century. List of compositions by Ottorino Respighi, His compositions r ...

.Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:34.

Biography

Early years

Rimsky-Korsakov was born in

Rimsky-Korsakov was born in Tikhvin

Tikhvin (russian: Ти́хвин; Veps: ) is a town and the administrative center of Tikhvinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on both banks of the Tikhvinka River in the east of the oblast, east of St. Petersburg. Tikhvin i ...

, east of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, into a Russian noble family. Tikhvin was a town of Novgorod Governorate

Novgorod Governorate (Pre-reformed rus, Новгоро́дская губе́рнія, r=Novgorodskaya guberniya, p=ˈnofɡərətskəjə ɡʊˈbʲernʲɪjə, t=Government of Novgorod), was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Ru ...

at that time.

Throughout history, members of the family served in Russian government and took various positions as governors and war generals.

Throughout history, members of the family served in Russian government and took various positions as governors and war generals. Ivan Rimsky-Korsakov

Ivan Nikolajevich Rimsky-Korsakov, né ''Korsav'' (29 June 1754 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire – 31 July 1831 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire) was a Russian courtier and lover of Catherine the Great from 1778 to 1779. He was a memb ...

was famously a lover of Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

.''Tatiana Rimskaya-Korsakova (2008)''N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov. From the Family Letters

– Saint Petersburg: Compositor, 247 pages, pp. 8–9 By a Tsar's decree on May 15, 1677, 18 representatives of the Korsakov family acquired the right to be called the Rimsky-Korsakov family (Russian adjective 'Rimsky' means 'Roman') since the family "had a beginning within the Roman borders", i.e.

Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic since 1 ...

, which used to be a part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. In 1390, Wenceslaus Korsak moved to the Grand Prince Vasily I of Moscow

Vasily I Dmitriyevich ( rus, Василий I Дмитриевич, Vasiliy I Dmitriyevich; 30 December 137127 February 1425) was the Grand Prince of Moscow ( r. 1389–1425), heir of Dmitry Donskoy (r. 1359–1389). He ruled as a Golden Horde ...

from the Duchy of Lithuania

The Duchy of Lithuania ( la, Ducatus Lithuaniae; lt, Lietuvos kunigaikštystė) was a state-territorial formation of ethnic Lithuanians that existed from the 13th century to 1413. For most of its existence, it was a constituent part and a nucle ...

.

The father of the composer, Andrei Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov (1784–1862), was one of the six illegitimate sons of Avdotya Yakovlevna, daughter of an Orthodox priest

Presbyter is, in the Bible, a synonym for ''bishop'' (''episkopos''), referring to a leader in local church congregations. In modern Eastern Orthodox usage, it is distinct from ''bishop'' and synonymous with priest. Its literal meaning in Greek (' ...

from Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

, and lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Peter Voinovich Rimsky-Korsakov, who had to officially adopt his own children as he couldn't marry their mother because of her lower social status. Using his friendship with Aleksey Arakcheyev

Count Alexey Andreyevich Arakcheyev or Arakcheev (russian: граф Алексе́й Андре́евич Аракче́ев) ( – ) was an Imperial Russian general and statesman during the reign of Tsar Alexander I.

He served under Tsars Paul I ...

, he managed to grant them all the privileges of the noble family. Andrei went on to serve in the Interior Ministry of the Russian Empire, as vice-governor of Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ol ...

, and in the Volhynian Governorate

Volhynian Governorate or Volyn Governorate (russian: Волы́нская губе́рния, translit=Volynskaja gubernija, uk, Волинська губернія, translit=Volynska huberniia) was an administrative-territorial unit initially ...

. The composer's mother, Sofya Vasilievna Rimskaya-Korsakova (1802–1890), was also born as an illegitimate daughter of a peasant serf and Vasily Fedorovich Skaryatin, a wealthy landlord who belonged to the noble Russian family that originated during the 16th century. Her father raised her in full comfort, yet under an improvised surname, Vasilieva, and with no legal status. By the time Andrei Petrovich met her, he was already a widower: his first wife, knyaz

, or ( Old Church Slavonic: Кнѧзь) is a historical Slavic title, used both as a royal and noble title in different times of history and different ancient Slavic lands. It is usually translated into English as prince or duke, dependi ...

na Ekaterina Meshcherskaya, died just nine months after their marriage. Since Skaryatin found him unsuitable for his daughter, Andrei secretly "stole" his bride from the father's house and brought her to Saint Petersburg, where they married.

The Rimsky-Korsakov family had a long line of military and naval service. Nikolai's older brother Voin, 22 years his senior, became a well-known navigator and explorer and had a powerful influence on Nikolai's life.Taruskin, ''Music'', p. 166. He later recalled that his mother played the piano a little, and his father could play a few songs on the piano by ear. Beginning at six, he took piano lessons from local teachers and showed a talent for aural skills,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:27. but he showed a lack of interest, playing, as he later wrote, "badly, carelessly, ... poor at keeping time".

Although he started composing by age 10, Rimsky-Korsakov preferred literature to music. He later wrote that from his reading, and tales of his brother's exploits, he developed a poetic love for the sea "without ever having seen it". This love, with subtle prompting from Voin, encouraged the 12-year-old to join the

The Rimsky-Korsakov family had a long line of military and naval service. Nikolai's older brother Voin, 22 years his senior, became a well-known navigator and explorer and had a powerful influence on Nikolai's life.Taruskin, ''Music'', p. 166. He later recalled that his mother played the piano a little, and his father could play a few songs on the piano by ear. Beginning at six, he took piano lessons from local teachers and showed a talent for aural skills,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:27. but he showed a lack of interest, playing, as he later wrote, "badly, carelessly, ... poor at keeping time".

Although he started composing by age 10, Rimsky-Korsakov preferred literature to music. He later wrote that from his reading, and tales of his brother's exploits, he developed a poetic love for the sea "without ever having seen it". This love, with subtle prompting from Voin, encouraged the 12-year-old to join the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

. He studied at the School for Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in Saint Petersburg and at 18 took his final examination in April 1862.

While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh. Voin, now director of the school, sanctioned these lessons because he hoped they would help Nikolai develop social skills and overcome his shyness. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that, while "indifferent" to lessons, he developed a love for music, fostered by visits to the opera and, later, orchestral concerts.

Ulikh perceived Rimsky-Korsakov's musical talent and recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore Canillé). Beginning in late 1859, Rimsky-Korsakov took lessons in piano and composition from Kanille, whom he later credited as the inspiration for devoting his life to composition.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 16. Through Kanille, he was exposed to a great deal of new music, including

While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh. Voin, now director of the school, sanctioned these lessons because he hoped they would help Nikolai develop social skills and overcome his shyness. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that, while "indifferent" to lessons, he developed a love for music, fostered by visits to the opera and, later, orchestral concerts.

Ulikh perceived Rimsky-Korsakov's musical talent and recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore Canillé). Beginning in late 1859, Rimsky-Korsakov took lessons in piano and composition from Kanille, whom he later credited as the inspiration for devoting his life to composition.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 16. Through Kanille, he was exposed to a great deal of new music, including Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, link=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka., mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recogni ...

and Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

.Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove'' (2001), 21:400. Voin cancelled his brother Nikolai's musical lessons when the latter reached age 17, feeling they no longer served a practical purpose.

Kanille told Rimsky-Korsakov to continue coming to him every Sunday, not for formal lessons but to play duets and discuss music. In November 1861, Kanille introduced the 18-year-old Nikolai to Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian: Miliy Alekseyevich Balakirev; ALA-LC system: ''Miliĭ Alekseevich Balakirev''; ISO 9 system: ''Milij Alekseevič Balakir ...

. Balakirev in turn introduced him to César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Ru ...

and Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

; all three were known as composers, despite only being in their 20s. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote, "With what delight I listened to ''real business'' discussions imsky-Korsakov's emphasisof instrumentation, part

Part, parts or PART may refer to:

People

*Armi Pärt (born 1991), Estonian handballer

*Arvo Pärt (born 1935), Estonian classical composer

*Brian Part (born 1962), American child actor

*Dealtry Charles Part (1882–1961), sheriff (1926–1927) an ...

writing, etc! And besides, how much talking there was about current musical matters! All at once I had been plunged into a new world, unknown to me, formerly only heard of in the society of my dilettante friends. That was truly a strong impression."

Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev prompted him to enrich himself in history, literature and criticism. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continue working on it despite his lack of formal musical training.

By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month cruise aboard the

Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev prompted him to enrich himself in history, literature and criticism. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continue working on it despite his lack of formal musical training.

By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month cruise aboard the clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "C ...

''Almaz'' in late 1862, he had completed and orchestrated three movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

of the symphony. He composed the slow movement during a stop in England and mailed the score to Balakirev before going back to sea.

At first, his work on the symphony kept Rimsky-Korsakov occupied during his cruise. He purchased scores at every port of call, along with a piano on which to play them, and filled his idle hours studying Berlioz's Treatise on Instrumentation

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

. He found time to read the works of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friends ...

and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as trea ...

; he saw London, Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

, and Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

during his stops in port. Eventually, the lack of outside musical stimuli dulled the young midshipman's hunger to learn. He wrote to Balakirev that after two years at sea he had neglected his musical lessons for months.

"Thoughts of becoming a musician and composer gradually left me altogether", he later recalled; "distant lands began to allure me, somehow, although, properly speaking, naval service never pleased me much and hardly suited my character at all."

Mentored by Balakirev; time with The Five

Once back in Saint Petersburg in May 1865, Rimsky-Korsakov's onshore duties consisted of a couple of hours of clerical duty each day, but he recalled that his desire to compose "had been stifled ... I did not concern myself with music at all." He wrote that contact with Balakirev in September 1865 encouraged him "to get accustomed to music and later to plunge into it". At Balakirev's suggestion, he wrote a trio to thescherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often ref ...

of the E-flat minor symphony, which it had lacked up to that point, and reorchestrated the entire symphony.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', pp. 58–59. Its first performance came in December of that year under Balakirev's direction in Saint Petersburg.Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:28. A second performance followed in March 1866 under the direction of Konstantin Lyadov (father of composer Anatoly Lyadov

Anatoly Konstantinovich Lyadov (russian: Анато́лий Константи́нович Ля́дов; ) was a Russian composer, teacher, and conductor (music), conductor.

Biography

Lyadov was born in 1855 in Saint Petersburg, St. Petersbur ...

).

Correspondence between Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev clearly shows that some ideas for the symphony originated with Balakirev, who seldom stopped at merely correcting a piece of music, and would often recompose it at the piano. Rimsky-Korsakov recalled,

A pupil like myself had to submit to Balakirev a proposed composition in its embryo, say, even the first four or eight bars. Balakirev would immediately make corrections, indicating how to recast such an embryo; he would criticize it, would praise and extol the first two bars, but would censure the next two, ridicule them, and try hard to make the author disgusted with them. Vivacity of composition and fertility were not at all in favor, frequent recasting was demanded, and the composition was extended over a long period of time under the cold control of self-criticism.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 29.

Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that "Balakirev had no difficulty in getting along with me. At his suggestion I most readily rewrote the symphonic movements composed by me and brought them to completion with the help of his advice and improvisations". Though Rimsky-Korsakov later found Balakirev's influence stifling, and broke free from it,Maes, p. 44. this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser. Under Balakirev's mentoring, Rimsky-Korsakov turned to other compositions. He began a symphony in B minor, but felt it too closely followed

Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that "Balakirev had no difficulty in getting along with me. At his suggestion I most readily rewrote the symphonic movements composed by me and brought them to completion with the help of his advice and improvisations". Though Rimsky-Korsakov later found Balakirev's influence stifling, and broke free from it,Maes, p. 44. this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser. Under Balakirev's mentoring, Rimsky-Korsakov turned to other compositions. He began a symphony in B minor, but felt it too closely followed Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's Ninth Symphony and abandoned it. He completed an Overture on Three Russian Themes, based on Balakirev's folksong overtures, as well as a Fantasia on Serbian Themes that was performed at a concert given for the delegates of the Slavonic Congress in 1867. In his review of this concert, nationalist critic Vladimir Stasov

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (also Stassov; rus, Влади́мир Васи́льевич Ста́сов; 14 January Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._2_January.html" ;"title="Adoption of ...

coined the phrase ''Moguchaya kuchka'' for the Balakirev circle (''Moguchaya kuchka'' is usually translated as "The Mighty Handful" or "The Five"). Rimsky-Korsakov also composed the initial versions of ''Sadko'' and ''Antar

Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR) is an independent, national non-government, not-for-profit, community-based organisation founded in 1997 which advocates for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Au ...

'', which cemented his reputation as a writer of orchestral works.

Rimsky-Korsakov socialized and discussed music with the other members of The Five; they critiqued one another's works in progress and collaborated on new pieces. He became friends with Alexander Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

, whose music "astonished" him.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 57. He spent an increasing amount of time with Mussorgsky. Balakirev and Mussorgsky played piano four-hand music, Mussorgsky would sing, and they frequently discussed other composers' works, with preferred tastes running "toward Glinka, Schumann and Beethoven's late quartets".Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 21. Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

was not thought of highly, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

and Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

"were considered out of date and naïve", and J.S. Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suite ...

merely mathematical and unfeeling. Berlioz "was highly esteemed", Liszt "crippled and perverted from a musical point of view ... even a caricature", and Wagner discussed little. Rimsky-Korsakov "listened to these opinions with avidity and absorbed the tastes of Balakirev, Cui and Mussorgsky without reasoning or examination". Often, the musical works in question "were played before me only in fragments, and I had no idea of the whole work". This, he wrote, did not stop him from accepting these judgments at face value and repeating them "as if I were thoroughly convinced of their truth".

Rimsky-Korsakov became especially appreciated within The Five, and among those who visited the circle, for his talents as an orchestrator. He was asked by Balakirev to orchestrate a Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

march for a concert in May 1868, by Cui to orchestrate the opening chorus of his opera '' William Ratcliff'' and by Alexander Dargomyzhsky

Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky ( rus, link=no, Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский, Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomyzhskiy., ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪdʑ dərɡɐˈmɨʂskʲɪj, Ru-Aleksandr-Sergeevich- ...

, whose works were greatly appreciated by The Five and who was close to death, to orchestrate his opera '' The Stone Guest''.

In late 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov moved into Voin's former apartment, and invited Mussorgsky to be his roommate. The working arrangement they agreed upon was that Mussorgsky used the piano in the mornings while Rimsky-Korsakov worked on copying or orchestration. When Mussorgsky left for his civil service job at noon, Rimsky-Korsakov then used the piano. Time in the evenings was allotted by mutual agreement. "That autumn and winter the two of us accomplished a good deal", Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, "with constant exchange of ideas and plans. Mussorgsky composed and orchestrated the Polish act of ''Boris Godunov

Borís Fyodorovich Godunóv (; russian: Борис Фёдорович Годунов; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of his ...

'' and the folk scene 'Near Kromy.' I orchestrated and finished my '' Maid of Pskov''."

Professorship, marriage, inspector of bands

In 1871, the 27-year-old Rimsky-Korsakov became Professor of Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration) at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, as well as leader of the Orchestra Class. He retained his position in active naval service, and taught his classes in uniform (military officers in Russia were required to wear their uniforms every day, as they were considered to be always on duty). Rimsky-Korsakov explained in his memoirs that

Rimsky-Korsakov explained in his memoirs that Mikhaíl Azanchevsky

Mikhail Pavlovich (von) Azanchevsky (russian: Михаи́л Па́влович (фон) Азанче́вский), – ) was a Russian composer and music teacher. He was the director of the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1871-1876. Not long befor ...

had taken over that year as director of the Conservatory, and wanting new blood to freshen up teaching in those subjects,Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 116. had offered to pay generously for Rimsky-Korsakov's services. Biographer Mikhail Tsetlin

Mikhail Osipovich Tsetlin (russian: Михаи́л О́сипович Це́тлин, July 10, 1882, Moscow, Russian Empire, — November 10, 1945, New York City, United States) was a Russian poet, dramatist, novelist, memoirist, revolutionary and ...

(aka Mikhail Zetlin) suggests that Azanchevsky's motives might have been twofold. First, Rimsky-Korsakov was the member of the Five least criticized by its opponents, and inviting him to teach at the Conservatory may have been considered a safe way to show that all serious musicians were welcome there. Second, the offer may have been calculated to expose him to an academic climate in which he would write in a more conservative, Western-based style. Balakirev had opposed academic training in music with tremendous vigor,Maes, p. 39. but encouraged him to accept the post to convince others to join the nationalist musical cause.

Rimsky-Korsakov's reputation at this time was as a master of orchestration, based on ''Sadko'' and ''Antar''.Zetlin, p. 195. He had written these works mainly by intuition. His knowledge of musical theory was elemental; he had never written any counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

, could not harmonize a simple chorale

Chorale is the name of several related musical forms originating in the music genre of the Lutheran chorale:

* Hymn tune of a Lutheran hymn (e.g. the melody of "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme"), or a tune in a similar format (e.g. one of the t ...

, nor knew the names or intervals

Interval may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Interval (mathematics), a range of numbers

** Partially ordered set#Intervals, its generalization from numbers to arbitrary partially ordered sets

* A statistical level of measurement

* Interval est ...

of musical chords. He had never conducted an orchestra, and had been discouraged from doing so by the navy, which did not approve of his appearing on the podium in uniform. Aware of his technical shortcomings, Rimsky-Korsakov consulted Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, with whom he and the others in The Five had been in occasional contact. Tchaikovsky, unlike The Five, had received academic training in composition at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, and was serving as Professor of Music Theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

at the Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory (russian: Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, link=no) is a musical educational inst ...

. Tchaikovsky advised him to study.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that while teaching at the Conservatory he soon became "possibly its very best ''pupil'' imsky-Korsakov's emphasis judging by the quantity and value of the information it gave me!"Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 119. To prepare himself, and to stay at least one step ahead of his students, he took a three-year sabbatical from composing original works, and assiduously studied at home while he lectured at the Conservatory. He taught himself from textbooks,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:29. and followed a strict regimen of composing contrapuntal exercises, fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

s, chorales and ''a cappella

''A cappella'' (, also , ; ) music is a performance by a singer or a singing group without instrumental accompaniment, or a piece intended to be performed in this way. The term ''a cappella'' was originally intended to differentiate between Ren ...

'' choruses.

Rimsky-Korsakov eventually became an excellent teacher and a fervent believer in academic training.Maes, p. 170. He revised everything he had composed prior to 1874, even acclaimed works such as ''Sadko'' and ''Antar'', in a search for perfection that would remain with him throughout the rest of his life. Assigned to rehearse the Orchestra Class, he mastered the art of conducting. Dealing with orchestral textures as a conductor, and making suitable arrangements of musical works for the Orchestra Class, led to an increased interest in the art of orchestration, an area into which he would further indulge his studies as Inspector of Navy Bands. The score of his Third Symphony, written just after he had completed his three-year program of self-improvement, reflects his hands-on experience with the orchestra.

Professorship brought Rimsky-Korsakov financial security,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:28 which encouraged him to settle down and to start a family. In December 1871 he proposed to

Professorship brought Rimsky-Korsakov financial security,Abraham, ''New Grove (1980)'', 16:28 which encouraged him to settle down and to start a family. In December 1871 he proposed to Nadezhda Purgold

Nadezhda may refer to:

*Nadezhda (given name), people with the given name ''Nadezhda''

*Nadezhda (satellite), a series of Russian navigation satellites, of which one was launched in 1998

*2071 Nadezhda, an asteroid

*Nadezhda (cockroach), the first ...

, with whom he had developed a close relationship over weekly gatherings of The Five at the Purgold household. They married in July 1872, with Mussorgsky serving as best man. The Rimsky-Korsakovs had seven children. Their first son, Mikhail, became an entomologist while another son, Andrei

Andrei, Andrey or Andrej (in Cyrillic script: Андрэй , Андрей or Андреј) is a form of Andreas/Ἀνδρέας in Slavic languages and Romanian. People with the name include:

*Andrei of Polotsk (–1399), Lithuanian nobleman

*A ...

, became a musicologist, married the composer Yuliya Veysberg and wrote a multi-volume study of his father's life and work.

Nadezhda became a musical as well as domestic partner with her husband, much as Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

had been with her own husband Robert. She was beautiful, capable, strong-willed, and far better trained musically than her husband at the time they married—she had attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in the mid-1860s, studying piano with Anton Gerke (one of whose private students was Mussorgsky) and music theory with Nikolai Zaremba

Nikolai or Nicolaus Ivanovich von Zaremba (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Заре́мба; ) was a Russian musical theorist, teacher and composer. His most famous student was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who became his pupil in 1861. Ot ...

, who also taught Tchaikovsky.Neff, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:423. Nadezhda proved a fine and most demanding critic of her husband's work; her influence over him in musical matters was strong enough for Balakirev and Stasov to wonder whether she was leading him astray from their musical preferences.Frolova-Walker, ''New Grove (2001)'', 21:401. Musicologist Lyle Neff wrote that while Nadezhda gave up her own compositional career when she married Rimsky-Korsakov, she "had a considerable influence on the creation of imsky-Korsakov'sfirst three operas. She travelled with her husband, attended rehearsals and arranged compositions by him and others" for piano four hands, which she played with her husband. "Her last years were dedicated to issuing her husband's posthumous literary and musical legacy, maintaining standards for performance of his works ... and preparing material for a museum in his name."

In early 1873, the navy created the civilian post of Inspector of Naval Bands, with a rank of Collegiate Assessor, and appointed Rimsky-Korsakov. This kept him on the navy payroll and listed on the roster of the Chancellery of the Navy Department but allowed him to resign his commission. The composer commented, "I parted with delight with both my military status and my officer's uniform", he later wrote. "Henceforth I was a musician officially and incontestably." As Inspector, Rimsky-Korsakov applied himself with zeal to his duties. He visited naval bands throughout Russia, supervised the bandmasters and their appointments, reviewed the bands' repertoire, and inspected the quality of their instruments. He wrote a study program for a complement of music students who held navy fellowships at the Conservatory, and acted as an intermediary between the Conservatory and the navy. He also indulged in a long-standing desire to familiarize himself with the construction and playing technique of orchestral instruments. These studies prompted him to write a textbook on orchestration.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 136. He used the privileges of rank to exercise and expand upon his knowledge. He discussed arrangements of musical works for military band with bandmasters, encouraged and reviewed their efforts, held concerts at which he could hear these pieces, and orchestrated original works, and works by other composers, for military bands.

In March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties. He worked under Balakirev in the

In early 1873, the navy created the civilian post of Inspector of Naval Bands, with a rank of Collegiate Assessor, and appointed Rimsky-Korsakov. This kept him on the navy payroll and listed on the roster of the Chancellery of the Navy Department but allowed him to resign his commission. The composer commented, "I parted with delight with both my military status and my officer's uniform", he later wrote. "Henceforth I was a musician officially and incontestably." As Inspector, Rimsky-Korsakov applied himself with zeal to his duties. He visited naval bands throughout Russia, supervised the bandmasters and their appointments, reviewed the bands' repertoire, and inspected the quality of their instruments. He wrote a study program for a complement of music students who held navy fellowships at the Conservatory, and acted as an intermediary between the Conservatory and the navy. He also indulged in a long-standing desire to familiarize himself with the construction and playing technique of orchestral instruments. These studies prompted him to write a textbook on orchestration.Rimsky-Korsakov, ''My Musical Life'', p. 136. He used the privileges of rank to exercise and expand upon his knowledge. He discussed arrangements of musical works for military band with bandmasters, encouraged and reviewed their efforts, held concerts at which he could hear these pieces, and orchestrated original works, and works by other composers, for military bands.

In March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties. He worked under Balakirev in the Court Chapel

A court chapel (German: Hofkapelle) is a chapel (building) and/or a chapel as a musical ensemble associated with a royal or noble court. Most of these are royal (court) chapels, but when the ruler of the court is not a king, the more generic "co ...

as a deputy until 1894, which allowed him to study Russian Orthodox church music. He also taught classes at the chapel, and wrote his textbook on harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

for use there and at the Conservatory.

Backlash and ''May Night''

Rimsky-Korsakov's studies and his change in attitude regarding music education brought him the scorn of his fellow nationalists, who thought he was throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues andsonata

Sonata (; Italian: , pl. ''sonate''; from Latin and Italian: ''sonare'' rchaic Italian; replaced in the modern language by ''suonare'' "to sound"), in music, literally means a piece ''played'' as opposed to a cantata (Latin and Italian ''cant ...

s.Schonberg, p. 363. After he strove "to crowd in as much counterpoint as possible" into his Third Symphony, he wrote chamber

Chamber or the chamber may refer to:

In government and organizations

*Chamber of commerce, an organization of business owners to promote commercial interests

*Legislative chamber, in politics

*Debate chamber, the space or room that houses deliber ...

works adhering strictly to classical models, including a string sextet, a string quartet in F major (Op. 12) and a quintet for flute, clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano in B-flat. About the quartet and the symphony, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

, that they "were filled with a host of clever things but ... ereimbued with a dryly pedantic character". Borodin commented that when he heard the symphony, he kept "feeling that this is the work of a German ''Herr Professor'' who has put on his glasses and is about to write ''Eine grosse Symphonie in C''".

According to Rimsky-Korsakov, the other members of the Five showed little enthusiasm for the symphony, and less still for the quartet. Nor was his public debut as a conductor, at an 1874 charity concert where he led the orchestra in the new symphony, considered favorably by his compatriots. He later wrote that "they began, indeed, to look down upon me as one on the downward path". Worse still to Rimsky-Korsakov was the faint praise given by Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sai ...