Richard Sutherland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Returning to the United States, Sutherland married Josephine Whiteside in 1920. They had one child, a daughter named Natalie.

Sutherland was an instructor at the

Returning to the United States, Sutherland married Josephine Whiteside in 1920. They had one child, a daughter named Natalie.

Sutherland was an instructor at the

As tensions with Japan rose, Sutherland was promoted to full

As tensions with Japan rose, Sutherland was promoted to full  It was Sutherland who represented MacArthur before the

It was Sutherland who represented MacArthur before the

Burial Detail: Sutherland, Richard K. (Section 30, Grave 694-1-2)

– ANC Explorer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sutherland, Richard K. 1893 births 1966 deaths United States Army Field Artillery Branch personnel United States Army Infantry Branch personnel Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Davis & Elkins College alumni Military personnel from Maryland Military personnel from West Virginia People from Elkins, West Virginia People from Hancock, Maryland Phillips Academy alumni Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Star Recipients of the Silver Star United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals United States Army personnel of World War I Yale University alumni

Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

Richard Kerens Sutherland (27 November 1893 – 25 June 1966) was a United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

officer during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. He served as General of the Army Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

's Chief of Staff in the South West Pacific Area

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the ...

during the war.

Early life and education

Sutherland was born inHancock, Maryland

Hancock is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 1,546 at the 2010 census. The Western Maryland community is notable for being located at the narrowest part of the state. The north-south distance from the Penns ...

, on 27 November 1893, the only son among the six children of Howard Sutherland

Howard Sutherland (September 8, 1865March 12, 1950) was an American politician. He was a Republican who represented West Virginia in both houses of the United States Congress.

Sutherland was born near Kirkwood, Missouri. He lived in Missouri un ...

, who later became a US Senator from West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

, and Effie Harris Sutherland. Sutherland was raised and spent his adolescence and early adulthood in Elkins, West Virginia.

Sutherland was educated at Davis and Elkins College

Davis & Elkins College (D&E) is a private college in Elkins, West Virginia.

History

The school was founded in 1904 and is affiliated with the Presbyterian Church. It was named for Henry G. Davis and his son-in-law Stephen B. Elkins, who were b ...

, Phillips Academy, from which he graduated in 1911, and Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

in 1916.

While at Yale, Sutherland joined ROTC. In July 1916, he enlisted as a private in the Connecticut National Guard.

Career

First World War

Later that year, the National Guard was federalized and Sutherland served on the Mexican border during thePancho Villa Expedition

The Pancho Villa Expedition—now known officially in the United States as the Mexican Expedition, but originally referred to as the "Punitive Expedition, U.S. Army"—was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the p ...

. The future general soon accepted a National Guard commission as a second lieutenant in the field artillery in August 1916. In December 1916, he transferred to the Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

with a commission as a first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

in the Infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

branch. Sutherland was promoted to captain in 1917.

He served with the 2nd Division on the Western Front during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Sutherland was a student at a tank school in England.

Between the wars

Returning to the United States, Sutherland married Josephine Whiteside in 1920. They had one child, a daughter named Natalie.

Sutherland was an instructor at the

Returning to the United States, Sutherland married Josephine Whiteside in 1920. They had one child, a daughter named Natalie.

Sutherland was an instructor at the United States Army Infantry School

The United States Army Infantry School is a school located at Fort Benning, Georgia that is dedicated to training infantrymen for service in the United States Army.

Organization

The school is made up of the following components:

* 197th Infantr ...

from 1920 to 1923 and professor of military science and tactics at the Shattuck School from 1923 to 1928. He graduated from the Command and General Staff College

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

in 1928. Fluent in French, Sutherland attended the ''École supérieure de guerre'' in 1930. During 1932 and 1933, he attended the U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a U.S. Army educational institution in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle Barracks. It provides graduate-level instruction to senior military officer ...

. He then served with the Operations and Training Division of the War Department General Staff.

In 1937, Sutherland went to Tientsin, China, in command of a battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions a ...

of the 15th Infantry; however, he was not promoted to major until March 1938, when he was assigned to the Office of the Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government (Philippines), Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, under General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

with the "local rank" of lieutenant colonel. Sutherland was promoted to the rank in July of that year. Sutherland soon eased his superior, Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

out of his position and became MacArthur's chief of staff.

World War II

As tensions with Japan rose, Sutherland was promoted to full

As tensions with Japan rose, Sutherland was promoted to full colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

, then to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in July 1941 and major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

in December 1941.

Following the fall of Manila, MacArthur's headquarters moved to the island fortress of Corregidor, where it was the target of numerous Japanese air raids, forcing the headquarters to move into the Malinta Tunnel

The Malinta Tunnel is a tunnel complex built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers on the island of Corregidor in the Philippines. It was initially used as a bomb-proof storage and personnel bunker, but was later equipped as a 1,000- ...

. Sutherland was a frequent visitor to the front on Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the enti ...

. He was given a cash payment of $75,000 by President Quezon. In March 1942, MacArthur was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to relocate to Australia. Sutherland selected the group of advisers and subordinate military commanders that would accompany MacArthur and escape from the Philippines in four PT boats. Sutherland would remain MacArthur's chief of staff for the entire war.

Sutherland attracted antagonism from subordinate American and Australian officers because of perceptions that he was high-handed and overprotective of MacArthur. Sutherland was often given the role of "hatchet man". Bad news invariably came through Sutherland rather than from MacArthur himself.

According to some sources he contributed to a rift between MacArthur and the first SWPA air forces commander, Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

George Brett

George Howard Brett (born May 15, 1953) is an American former professional baseball player who played all of his 21 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a third baseman for the Kansas City Royals.

Brett's 3,154 career hits are second-mo ...

. Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

George Kenney

George Churchill Kenney (August 6, 1889 – August 9, 1977) was a United States Army general during World War II. He is best known as the commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), a position he held between Augu ...

, Brett's successor, became so frustrated with Sutherland in one meeting, that Kenney drew a dot on a plain page of paper and said: "the dot represents what you know about air operations, the entire rest of the paper what I know."

Sutherland had been taught to fly in 1940 by US Army Air Corps instructors at the Philippine Army Training Center and had been awarded a civil pilot's license by the Civil Aeronautics Association. Flying then became one of his favourite recreational activities. Throughout the war, he flew often as a co-pilot with General MacArthur's personal pilot, Weldon "Dusty" Rhoades. In March 1943 he asked to be formally recognised as a "service pilot", a form of pilot restricted to non-combat duties. His request was turned down by the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Henry H. Arnold on the grounds that he was over the age limit and not performing flying duties. However, Sutherland secured an official pilot's rating under Philippine Army regulations in 1945.

In 1943 Sutherland and Kenney took part in an effort to promote General MacArthur's candidacy for the Presidency, working with Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

to get the War Department to rescind the order that prevented MacArthur from seeking or accepting political office.

It was Sutherland who represented MacArthur before the

It was Sutherland who represented MacArthur before the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

on this and other occasions. Sutherland opened, read, and frequently answered all communications with MacArthur, including those addressed to him personally or "eyes only". Some decisions often attributed to MacArthur were actually taken by Sutherland. For example, the decision to bypass Mindanao and move on directly to Leyte was taken by Sutherland on MacArthur's behalf, while MacArthur was traveling under radio silence.

Sutherland's conduct in Washington enraged Army Chief of Staff General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Marshall

Marshall may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Marshall, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria

Canada

* Marshall, Saskatchewan

* The Marshall, a mountain in British Columbia

Liberia

* Marshall, Liberia

Marshall Islands

* Marshall Islands, an i ...

. He prepared a letter that he never sent to MacArthur saying Sutherland was ''"totally lacking in the facility of dealing with others.... He antagonized almost every official in the War Department with whom he came in contact and made our dealings with the Navy exceptionally difficult. Unfortunately he appears utterly unaware of the effects of his methods, but to put it bluntly, his attitude in almost every case seems to have been that he knew it all and nobody else knew much of anything."''

When MacArthur discovered that Eisenhower had promoted his chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith

General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) during the Tunisia Campai ...

, to the rank of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

in January 1944, he immediately arranged for Sutherland to be promoted to the same rank.

Affair with Elaine Clark

During the time while MacArthur's GHQ SWPA was located inMelbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Sutherland met Elaine Bessemer Clark, the socialite daughter of Norman Brookes. Her husband, a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer, was serving overseas. When GHQ moved to Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

in July 1942, Clark moved with it, as did two other civilian women, Beryl Stevenson and Louise Mowat, who worked as secretaries for Generals Kenney and Richard Marshall respectively. Sutherland installed Clark as the receptionist at the AMP Building, where MacArthur had his headquarters.

When GHQ began planning to move forward to New Guinea, Sutherland requested personnel from the Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States ...

to replace civilian employees of GHQ who, by agreement between MacArthur and the Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He led the country for the majority of World War II, including all but the last few ...

, could not be sent outside Australia. Sutherland further asked for direct commissions for Clark, Mowat and Stevenson. This exploited a loophole whereby enlistments in the Women's Army Corps were restricted to American citizens, but officer commissions were not. Major General Miller G. White, the U. S. Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, and Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby

Oveta Culp Hobby (January 19, 1905 – August 16, 1995) was an American politician and businessperson who served as the first United States secretary of health, education, and welfare from 1953 to 1955. A member of the Republican Party, Hobby wa ...

, the commanding officer of the Women's Army Corps, were strongly opposed; but they were overruled by Deputy Chief of Staff Joseph T. McNarney, on his being informed that the commissions were personally desired by MacArthur as essential to the operation of his headquarters and the prosecution of the war. Clark was commissioned as a captain, while the other two women, as well as General Eisenhower's driver, Kay Summersby

Kathleen Helen Summersby (née MacCarthy-Morrogh; 23 November 1908 – 20 January 1975), known as Kay Summersby, was a member of the British Mechanised Transport Corps during World War II, who served as a chauffeur and later as persona ...

, were commissioned as first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

s.

Although her rank was more a reflection of Sutherland's status rather than her own, Clark became an assistant to the headquarters commandant, with duties commensurate with her rank, and moved with Advance GHQ to Hollandia. However, her presence there, in contravention of MacArthur's agreement with Curtin, brought down the displeasure of MacArthur, who ordered her to be returned to Australia, first from Hollandia, and later from the Philippines. That Sutherland defied MacArthur on this matter caused a rift between the two.

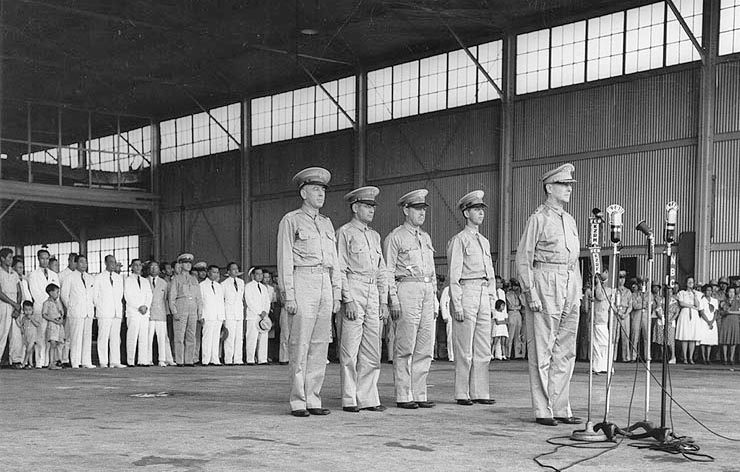

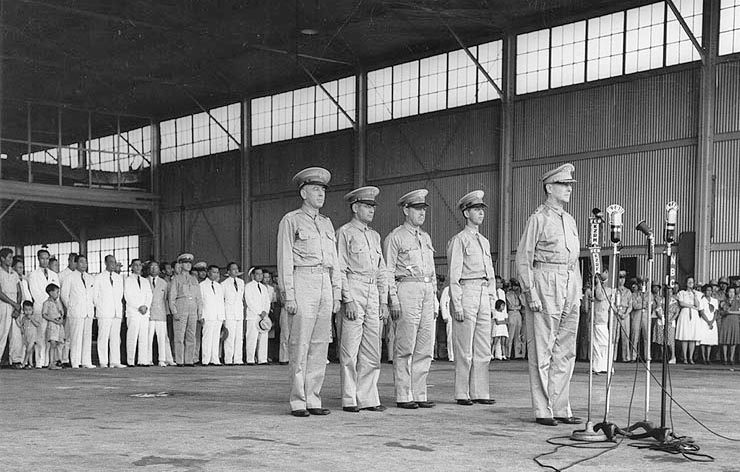

Japanese surrender

At the Japanese surrender inTokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populous ...

on 2 September 1945, the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

representative, Colonel L. Moore Cosgrave, signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that formalized the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of hostilities in World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan and from the Allied n ...

underneath, instead of on, the line for Canada. The Japanese drew attention to the error. Sutherland ran two strokes of his pen through the names of the four countries above the misplaced signatures and wrote them in where they belonged. The Japanese then accepted the corrected document.

Later life and death

Sutherland retired from the U.S. Army shortly after the Japanese surrender. Returning home, he confessed his affair to Josephine and was ultimately reconciled with her. Letters from Clark were intercepted and destroyed by Natalie. After the death of Josephine on 30 December 1957, he married Virginia Shaw Root in 1962. Sutherland died atWalter Reed Army Medical Center

The Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC)known as Walter Reed General Hospital (WRGH) until 1951was the United States Army, U.S. Army's flagship medical center from 1909 to 2011. Located on in the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, it se ...

on 25 June 1966. His funeral was held at the Fort Myer

Fort Myer is the previous name used for a U.S. Army post next to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, and across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Founded during the American Civil War as Fort Cass and Fort Whipple, ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

chapel on 29 June 1966 and he is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

along with other family members.– ANC Explorer

Decorations and medals

Dates of rank

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sutherland, Richard K. 1893 births 1966 deaths United States Army Field Artillery Branch personnel United States Army Infantry Branch personnel Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Davis & Elkins College alumni Military personnel from Maryland Military personnel from West Virginia People from Elkins, West Virginia People from Hancock, Maryland Phillips Academy alumni Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Star Recipients of the Silver Star United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals United States Army personnel of World War I Yale University alumni