Richard de Belmeis I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard de Belmeis I (or de Beaumais) (died 1127) was a medieval cleric, administrator, judge and politician. Beginning as a minor landowner and steward in

accessed on 28 October 2007 The attribution is now regarded as not fully proven.J.F.A. Mason: Oxford DNB article

/ref> It is made up of two very common French

/ref> and in one is described as ''dapifer'' for Shropshire. Richard also seems to have been employed in

Richard seems to have avoided entanglement in the revolt of

Richard seems to have avoided entanglement in the revolt of

/ref> It seems, therefore, that Richard was not in Shropshire at that time, but in Sussex. He was probably sent to Shrewsbury late in 1102, after Henry had dealt with Robert of Bellême's Welsh allies, imprisoning

/ref> It is possible that he was addressed on occasion as the

Richard was elected to the

Richard was elected to the

/ref> On 27 June 1115 he was at the enthronement of Ralph d'Escures as Archbishop of Canterbury. On 28 December that year he accompanied the king and queen to the consecration of

/ref> He participated in the consecration of several other bishops. On 4 April 1120 it was when

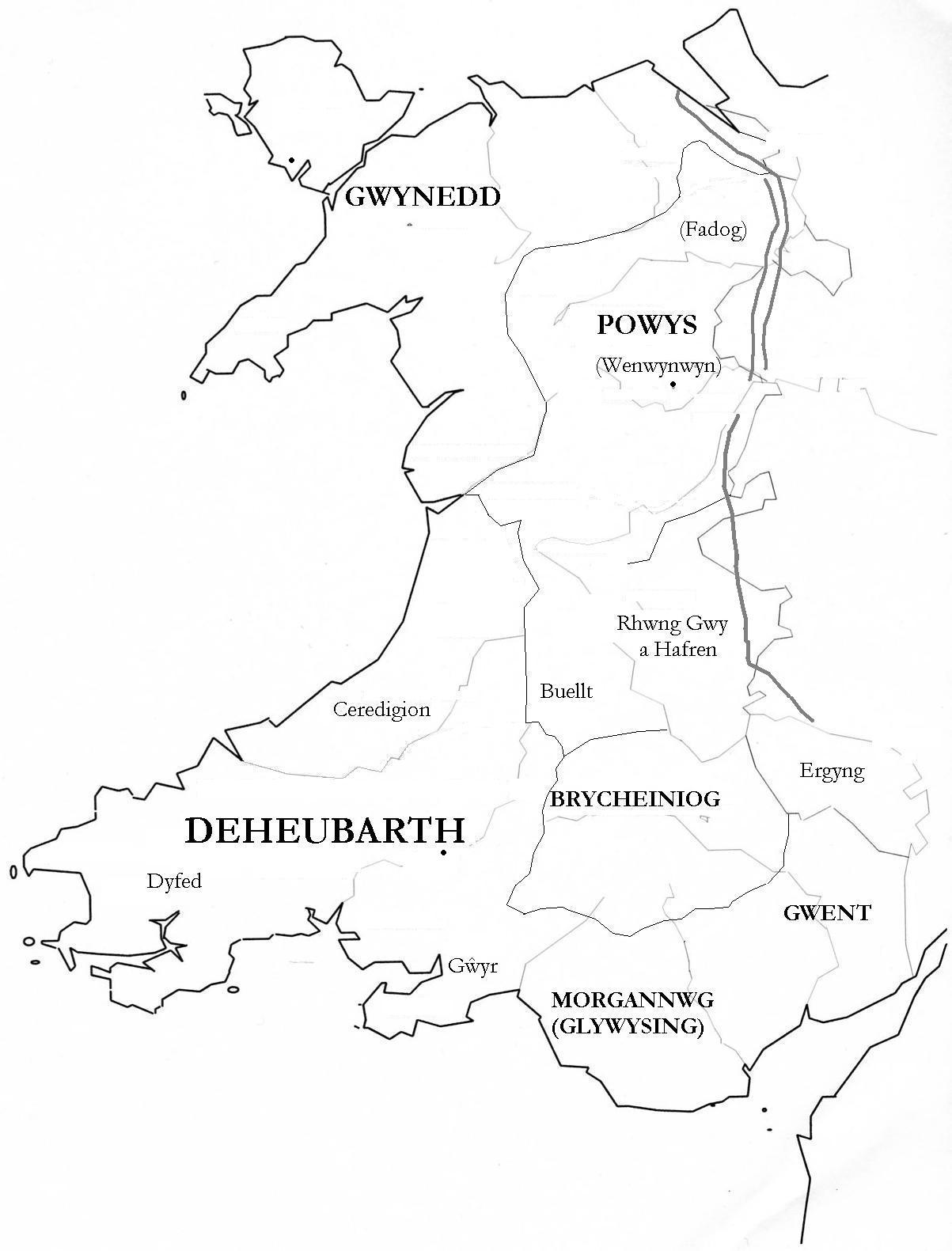

Richard's best-documented interventions in Wales date from the period immediately after his elevation to the episcopate in 1108. Richard's meddling in the complex dynastic politics of Wales was not always successful and Lloyd comments that “Bishop Richard was cynically indifferent to the crimes of Welshmen against each other.”Lloyd, p.421

Richard's best-documented interventions in Wales date from the period immediately after his elevation to the episcopate in 1108. Richard's meddling in the complex dynastic politics of Wales was not always successful and Lloyd comments that “Bishop Richard was cynically indifferent to the crimes of Welshmen against each other.”Lloyd, p.421

/ref> The imprisonment of Iorwerth had left a partial power vacuum in

/ref> Succeeding his father in Powys, he was able in 1113 to blind Madog in revenge for his father's murder and to survive a full-scale royal invasion in the following year. Eyton comments on Richard's part in these events: “The grossest treachery seems to have pervaded this part of his policy.”

/ref> Fulk clarified the situation in letters to the king, the Archbishop and other notables. Although Richard directed that the estate be restored to the abbey, its status was contested by his successors for decades: by Philip de Belmeis in 1127, although he quickly defaulted;Eyton, Volume 2, p.201

/ref> a few decades later by his younger son, Ranulph, who ultimately recognised the abbey's rights in return for acceptance into its fraternity; in 1212 by Roger de la Zouche, who continued his suit for years unsuccessfully. Richard also restored to the abbey the

Richard became the originator of both ecclesiastical and secular dynasties. He had at least two sons, Walter and William. Walter was a canon of London, holding the prebend of Newington, and William was

Richard became the originator of both ecclesiastical and secular dynasties. He had at least two sons, Walter and William. Walter was a canon of London, holding the prebend of Newington, and William was

Greenway (1968)

/ref>

Volume 1 (1854)Volume 2 (1855)Volume 3 (1856)

*Forester, Thomas (1854)

''The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy by Ordericus Vitalis, Volume 3''

Bohn, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B. (Editors); Angold, M. J.; Baugh, G. C.; Chibnall, Marjorie M.; Cox, D. C.; Price, D. T. W.; Tomlinson, Margaret; Trinder, B. S.; (1973)

''A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2''

Institute of Historical Research, accessed 9 December 2014. *Greenway, Diana (editor) (1968)

''Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300: Volume 1, St. Paul's, London''

Institute of Historical Research, London, accessed 18 December 2014. * *Johnson, Charles and Cronne, H.A. (eds) (1956)

''Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, Volume 2''

Oxford, accessed 23 January 2015 at Internet Archive. * Lloyd, John Edward (1912)

A History of Wales from Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Volume 2

2nd edition, Longmans, Green, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * Owen, Hugh and Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825)

''A History of Shrewsbury, Volume 2''

Harding and Lepard, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * Page, William and Round, J Horace (1907)

''A History of the County of Essex: Volume 2''

, Institute of Historical Research, accessed 5 January 2015. *Palmer, John, and Slater, George

''Domesday Book Shropshire''

accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * *Poole, Austin Lane (1951). ''From Domeday Book to Magna Carta'', Oxford. *Rule, Martin (editor) (1884)

''Eadmeri Historia Novorum in Anglia''

Longman, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Belmeis I, Richard de Bishops of London 1127 deaths Year of birth missing Anglo-Normans 12th-century English Roman Catholic bishops Politicians from Shropshire People from Tendring (district) Anglo-Normans in Wales Clergy from Shropshire

Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

, he became Henry I's chief agent in the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

and in 1108 was appointed Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. He founded St Osyth's Priory in Essex and was succeeded by a considerable dynasty of clerical politicians and landowners.

Identity

Richard's toponymic byname is given in modern accounts as ''de Belmeis''. Occasionally the form ''de Beaumais'' is encountered. This is based on the modern spelling of the village from which his family perhaps originated: Beaumais-sur-Dive, which is east ofFalaise

Falaise may refer to:

Places

* Falaise, Ardennes, France

* Falaise, Calvados, France

** The Falaise pocket was the site of a battle in the Second World War

* La Falaise, in the Yvelines ''département'', France

* The Falaise escarpment in Quebe ...

, in the Calvados

Calvados (, , ) is a brandy from Normandy in France, made from apples or pears, or from apples with pears.

History In France

Apple orchards and brewers are mentioned as far back as the 8th century by Charlemagne. The first known record of Norm ...

region of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

.British History Online Bishops of Londonaccessed on 28 October 2007 The attribution is now regarded as not fully proven.J.F.A. Mason: Oxford DNB article

/ref> It is made up of two very common French

toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

elements, meaning “attractive estate”: there is a village called Aubermesnil-Beaumais elsewhere in Normandy.

Whatever the form of his name, Richard is easily confused with his namesake and nephew, Richard de Belmeis II, who was also a 12th-century Bishop of London. Tout

A tout is any person who solicits business or employment in a persistent and annoying manner (generally equivalent to a ''solicitor'' or '' barker'' in American English, or a ''spruiker'' in Australian English).

An example would be a person who ...

refers to Richard I by the surname ''Rufus'', T.F. Tout: DNB article which creates further confusion. His epitaph shows that he was called Rufus, but the name, in the form Ruffus, is now generally reserved for an Archdeacon of Essex

The Archdeacon of West Ham is a senior ecclesiastical officer – in charge of the Archdeaconry of West Ham – in the Church of England Diocese of Chelmsford. The current archdeacon is Elwin Cockett.

Brief history

Historically, the Archdeaconry ...

a brother of Richard Belmeis II and thus another nephew of Richard Belmeis I. A further, later, Richard Ruffus may have been a son of the archdeacon. The family tree below attempts to clarify the relationships, which are still not beyond doubt.

Background and early life

Richard's background seems to lie in the lower reaches of the Norman landowning class. He is thought to be the Richard whom the Domesday enquiry found holding the very small manor of Meadowley, due west ofBridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a town in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the 2011 Census was 12,079.

History

B ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

. This he held as a tenant of Helgot, who held it of Roger Montgomery

Roger Montgomery (1925–2003) was an American architect, and Professor at Washington University in St. Louis and University of California, Berkeley.

Early life and education

Roger Montgomery was born in New York City to parents Graham Livings ...

, the great territorial magnate who dominated the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

. Meadowley was 6 ploughlands in extent and was populated by just five families: 3 slaves and 2 bordars

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. However, there were evidently signs of revival in Richard's hands. In Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

's time it had been worth 30 shillings, but it had sunk to only 2 shillings by the time Richard acquired it, since when it had risen again to 11 shillings. Richard also held three hides worth of land as a tenant of Helgot at Preen, to the north-west of Meadowley. Here he let a hide to Godebold, a priest who was a crony of Earl Roger. Godebold at this time was much wealthier than Richard and held a large number of properties that had been intended as prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

s of the collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a ...

of St Alkmund in Shrewsbury.

Richard seems to have become steward of Earl Roger and appears as a witness in charters, both genuine and spurious, granted by Roger and his son, Hugh

Hugh may refer to:

*Hugh (given name)

Noblemen and clergy French

* Hugh the Great (died 956), Duke of the Franks

* Hugh Magnus of France (1007–1025), co-King of France under his father, Robert II

* Hugh, Duke of Alsace (died 895), modern-day ...

to Shrewsbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Shrewsbury (commonly known as Shrewsbury Abbey) is an ancient foundation in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was founded in 1083 as a Benedictine monastery by the Norm ...

,Eyton, Volume 2, p.193/ref> and in one is described as ''dapifer'' for Shropshire. Richard also seems to have been employed in

Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

, where the Montgomery earls had substantial holdings.

Viceroy of Shropshire

Richard seems to have avoided entanglement in the revolt of

Richard seems to have avoided entanglement in the revolt of Robert of Bellême, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury

Robert de Bellême ( – after 1130), seigneur de Bellême (or Belèsme), seigneur de Montgomery, viscount of the Hiémois, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury and Count of Ponthieu, was an Anglo-Norman nobleman, and one of the most prominent figures in th ...

, and consequently emerged in Henry I's favour. Probably in autumn 1102, Henry ordered “Richard de Belmes”, Robert of Falaise and all the baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

s of Sussex to secure for Ralph de Luffa

Ralph de Luffa (or Ralph Luffa (died 1123) was an English bishop of Chichester, from 1091 to 1123. He built extensively on his cathedral as well as being praised by contemporary writers as an exemplary bishop. He took little part in the Investit ...

, the Bishop of Chichester

The Bishop of Chichester is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers the counties of East and West Sussex. The see is based in the City of Chichester where the bishop's seat ...

, lands near the town of Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ci ...

.Eyton, Volume 2, p.194/ref> It seems, therefore, that Richard was not in Shropshire at that time, but in Sussex. He was probably sent to Shrewsbury late in 1102, after Henry had dealt with Robert of Bellême's Welsh allies, imprisoning

Iorwerth ap Bleddyn Iorwerth ap Bleddyn (1053–1111) was a prince of Powys in eastern Wales.

Iorwerth was the son of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn who was king of both Powys and Gwynedd. When Bleddyn was killed in 1075, Powys was divided between three of his sons, Iorwerth, Cad ...

, a powerful Welsh leader who had played a prominent but equivocal part in events. Henry continued to treat Shropshire as a marcher lordship

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in Fran ...

but was determined not to install another earl who might threaten the monarchy. Probably at Christmas, Henry ordered Richard to help secure some land for the Abbey of Saint-Remi

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in ...

, which had a daughter house at Lapley Priory

Lapley Priory was a priory in Staffordshire, England. Founded at the very end of the Anglo-Saxon period, it was an alien priory, a satellite house of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Remi or Saint-Rémy at Reims in Northern France. After great ...

in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

and estates in Shropshire. This would indicate that he was fully in charge of Shropshire by the end of the year. However, the sequence of events is not certain.

Henry allowed Richard to take effective control of the county as a royal agent. He was described by Ordericus Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis ( la, Ordericus Vitalis; 16 February 1075 – ) was an English chronicler and Benedictine monk who wrote one of the great contemporary chronicles of 11th- and 12th-century Normandy and Anglo-Norman England. Modern historia ...

as the ''vicecomes'' or “viscount” of Shropshire, a term sometimes translated as Viceroy.Eyton, Volume 2, p.192/ref> It is possible that he was addressed on occasion as the

Sheriff of Shropshire

This is a list of sheriffs and high sheriffs of Shropshire

The sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the high sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of the responsibil ...

. He had a reputation as an expert on legal matters.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' p. 157 Hence he served as the justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

for the king at Shrewsbury, where his brief also included oversight of Welsh affairs.Crouch ''Reign of King Stephen'' p. 55 He was given substantial holdings in the county to support him in appropriate style. The priest Godebold had been succeeded by a son, Robert, and it seems likely that he had supported the rebels, as his estates were turned over to Richard. Other estates he acquired were Tong Tong may refer to:

Chinese

*Tang Dynasty, a dynasty in Chinese history when transliterated from Cantonese

*Tong (organization), a type of social organization found in Chinese immigrant communities

*''tong'', pronunciation of several Chinese char ...

and Donington, both of which had been retained as demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

by the Montgomery earls themselves. Despite his focus on Shropshire, the king seems to have continued regarding Richard as a Sussex magnate: as late as 1107 he heads a list of Sussex notables informed of the king's confirmation of the right of Chichester Cathedral to hold a fair in the town.

As Henry's viceroy, Richard made a considerable impact on the county. On occasion he convened and presided over ecclesiastical synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

s: Even after he became Bishop of London, he had no obvious authority for doing this, as Shropshire fell within the Diocese of Lichfield

The Diocese of Lichfield is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury, England. The bishop's seat is located in the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Chad in the city of Lichfield. The diocese covers of seve ...

. His decisions at assemblies at Wistanstow

Wistanstow is a village and parish in Shropshire, England. Wistanstow is located about south of Church Stretton and north of Ludlow. It is about north of Craven Arms. It is just off the main Shrewsbury- Hereford road, the A49. The large par ...

in 1110 and Castle Holdgate in 1115 greatly increased the powers and privileges of Wenlock Priory

Wenlock Priory, or St Milburga's Priory, is a ruined 12th-century monastery, located in Much Wenlock, Shropshire, at . Roger de Montgomery re-founded the Priory as a Cluniac house between 1079 and 1082, on the site of an earlier 7th-century mon ...

by recognising it as the mother church of an extensive parish and made it an important force in the region. Richard granted his land at Preen to Wenlock Priory and this was later used to found a daughter house.

Bishop of London

Election and consecration

see of London

The Diocese of London forms part of the Church of England's Province of Canterbury in England.

It lies directly north of the Thames. For centuries the diocese covered a vast tract and bordered the dioceses of Norwich and Lincoln to the north ...

and invested with its temporalities

Temporalities or temporal goods are the secular properties and possessions of the church. The term is most often used to describe those properties (a ''Stift'' in German or ''sticht'' in Dutch) that were used to support a bishop or other religious ...

on 24 May 1108.Fryde, et al. ''Handbook of British Chronology'' p. 258 The date is known from Eadmer

Eadmer or Edmer ( – ) was an English historian, theologian, and ecclesiastic. He is known for being a contemporary biographer of his archbishop and companion, Saint Anselm, in his ''Vita Anselmi'', and for his ''Historia novorum in ...

, the contemporary historian and biographer of Anselm, who places Richard's election at Pentecost: 24 May in that year, according to the Julian Calendar, in which Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

was on 5 April. The king's confirmation affirms that he is granted “the see of London with the lands and men pertaining to it, and the castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

of Stortford.” Shortly afterwards, Henry restored to the canons of St Paul's a range of judicial powers and privileges they had enjoyed in the reign of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

.

It appears that he had so far been ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

only as a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

. Ordination as a priest was required before Richard could proceed to ordination as a bishop. Eadmer makes clear that he was ordained as a priest with many others by Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, at his manor of Mortlake

Mortlake is a suburban district of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames on the south bank of the River Thames between Kew and Barnes. Historically it was part of Surrey and until 1965 was in the Municipal Borough of Barnes. For many centu ...

. Anselm had only recently returned from a long exile after he and the king came to a resolution of their Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monast ...

, and it seems that there was a backlog of ordinations. Eadmer does not give a date as such but says that Anselm carried out these ordinations during ''jejunio quarti mensis'' - the “fast of the fourth months,” i.e. the Ember Days, which were the Wednesday, Friday and Saturday following Pentecost. Eyton reasoned that the ordination would therefore have been on 27, 29 or 30 May. However, ''Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicani'' gives the probable date as 14 June 1108, nevertheless citing Eadmer as evidence.

Richard was fairly typical of the men made bishops, even after Henry had made substantial concessions to the Church. Citing Richard as an example, Poole comments: “Piety in matters of religion was seldom the primary qualification in the election of bishops; the continued to be normally men of affairs, administrators, chosen for their experience in conducting the king's business.” What followed made clear that Richard was essentially a royal nominee, not really known, much less congenial, to Anselm and the supporters of Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be nam ...

. Eadmer says that the king went to embark for Normandy and waited until he received a blessing from Anselm, who then became very ill and was confined to his quarters. The king then sent William Giffard

William Giffard (died 23 January 1129),Franklin "Giffard, William" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' was the Lord Chancellor of England of William II and Henry I, from 1093 to 1101,Fryde, et al. ''Handbook of British Chronology'' p. 8 ...

, the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

and William Warelwast

William Warelwast (died 1137) was a medieval Norman cleric and Bishop of Exeter in England. Warelwast was a native of Normandy, but little is known about his background before 1087, when he appears as a royal clerk for King William II. Most o ...

, the Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. Since 30 April 2014 the ordinary has been Robert Atwell.

, who had taken opposite sides in the investiture dispute, to urging Anselm to look after his son and the kingdom and to make sure that Richard was soon ordained bishop at Chichester. The reason he gave was that Richard was a man of great ability for whom he had important business in the far west of the country. Anselm did expedite Richard's consecration as a bishop, which took place on 26 July 1108. However, he demurred at using Chichester Cathedral

Chichester Cathedral, formally known as the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Chichester. It is located in Chichester, in West Sussex, England. It was founded as a cathedral in 1075, when the seat of the ...

, preferring instead to use his own chapel at Pagham

Pagham is a coastal village and civil parish in the Arun district of West Sussex, England, with a population of around 6,100. It lies about two miles to the west of Bognor Regis.

Governance

Pagham is part of the electoral ward called Pagham a ...

, assisted by the bishops of Winchester, Chichester and Exeter, together with Roger of Salisbury

Roger of Salisbury (died 1139), was a Norman medieval bishop of Salisbury and the seventh Lord Chancellor and Lord Keeper of England.

Life

Roger was originally priest of a small chapel near Caen in Normandy. He was called "Roger, priest of the ch ...

, the Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset. The see is in the City of Salisbury where the bishop's seat ...

.

Primacy dispute

One of Richard's concerns was to promote the interests of theArchdiocese of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

, of which his own see formed a part. A dispute over the primacy between Canterbury and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

had already dragged on for some years. Anselm had been granted a personal primacy over the whole English church by the Papacy. However, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, archbishop-elect of York since May 1108 had used various stratagems to delay his own consecration, as it was clear Anselm was near to death. In May 1109, Anselm died and at Pentecost the king convened his court in London, where the bishops demanded that Thomas accept consecration. This was a unanimous call, including even Samson

Samson (; , '' he, Šīmšōn, label= none'', "man of the sun") was the last of the judges of the ancient Israelites mentioned in the Book of Judges (chapters 13 to 16) and one of the last leaders who "judged" Israel before the institution o ...

, the Bishop of Worcester

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, who was Thomas's father. Accordingly, Thomas was brought to consecration at St Paul's, Richard's seat, on 27 June. Seven bishops were scheduled to take part: Richard himself, William Giffard of Winchester, Ralph d'Escures

Ralph d'Escures (also known as RadulfEadmer. ''Eadmer’s History of Recent Events in England = Historia Novorum in Anglia''. Translated by Geoffrey Bosanquet. London: Cresset Press, 1964. ) (died 20 October 1122) was a medieval abbot of Séez, ...

, the Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was foun ...

, Herbert de Losinga

Herbert de Losinga (died 22 July 1119) was the first Bishop of Norwich. He founded Norwich Cathedral in 1096 when he was Bishop of Thetford.

Life

Losinga was born in Exmes, near Argentan, Normandy, the son of Robert de LosingaDoubleday and Page ...

, the Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in the ...

, Ralph of Chichester, Ranulf Flambard

Ranulf Flambard ( c. 1060 – 5 September 1128) was a medieval Norman Bishop of Durham and an influential government minister of King William Rufus of England. Ranulf was the son of a priest of Bayeux, Normandy, and his nickname Flambard m ...

, the Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

, and Hervey le Breton

Hervey le Breton (also known as Hervé le Breton; died 30 August 1131) was a Breton cleric who became Bishop of Bangor in Wales and later Bishop of Ely in England. Appointed to Bangor by King William II of England, when the Normans were advanc ...

, the king's confessor, currently unable to fulfil his role as Bishop of Bangor

The Bishop of Bangor is the ordinary of the Church in Wales Diocese of Bangor. The see is based in the city of Bangor where the bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Cathedral Church of Saint Deiniol.

The ''Report of the Commissioners appointed ...

but a bishop nevertheless. However, Richard refused to participate until Thomas had made a written profession of subordination. According to Eadmer, this was a comprehensive surrender of the primacy to Canterbury:

However, doubt was to return later about the wording. Once the required formalities had been carried out, Richard pronounced himself satisfied and the consecration went ahead, with Thomas subsequently receiving a pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropolit ...

from the Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

.

Richard was still determined to pursue his campaign against Thomas, and raised the issue of who should say mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

before the king at the Christmas court of 1109, which was held in London. Still an archbishop and a primate, Thomas claimed to be the senior bishop in the country because of the continuing vacancy at Canterbury. However, Richard claimed to be the senior bishop and dean of the Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

, and thus the archbishop's deputy. Moreover, his predecessor Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

had been the one to crown Henry in 1100, when there was no Archbishop of Canterbury available. Richard celebrated the mass but the argument was pursued with renewed vigour, actually at the king's dinner table, until Henry sent both bishops home and remitted the issue to the future archbishop of Canterbury. Tout thought that Richard himself had aspirations to become archbishop, although it was not to be. Ralph d'Escures was already acquiring administrative authority within the province and, after prolonged wrangling, was to emerge as the next archbishop.

Episcopal business

Richard took part in settling numerous ecclesiastical and secular matters of his day. He was a witness to the king's writ recognising the establishment of theDiocese of Ely

The Diocese of Ely is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury. It is headed by the Bishop of Ely, who sits at Ely Cathedral in Ely. There is one suffragan (subordinate) bishop, the Bishop of Huntingdon. The diocese now co ...

: this had been discussed for some time and adopted as policy by Anselm, but papal approval arrived only in 1109. Hervey le Breton, displaced from Bangor by the resurgence of the Kingdom of Gwynedd

The Kingdom of Gwynedd (Medieval Latin: ; Middle Welsh: ) was a Welsh kingdom and a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

Based in northwest Wales, th ...

, was translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

to the new see, which was created by the partition of the Diocese of Lincoln

The Diocese of Lincoln forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England. The present diocese covers the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire.

History

The diocese traces its roots in an unbroken line to the Pre-Reformation Diocese of Leices ...

.

Richard attended the king when he was waiting to embark for Normandy in 1111 and 1114.Eyton, Volume 2, p.198/ref> On 27 June 1115 he was at the enthronement of Ralph d'Escures as Archbishop of Canterbury. On 28 December that year he accompanied the king and queen to the consecration of

St Albans Abbey

St Albans Cathedral, officially the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban but often referred to locally as "the Abbey", is a Church of England cathedral in St Albans, England. Much of its architecture dates from Norman times. It ceased to be ...

.Eyton, Volume 2, p.199/ref> He participated in the consecration of several other bishops. On 4 April 1120 it was when

David the Scot

David the Scot (died c. 1138) was a Welsh or Irish cleric who was Bishop of Bangor from 1120 to 1138.

There is some doubt as to David's nationality, as he is variously described as Welsh or Irish. Many Irish men living outside Ireland at this ti ...

, a new Bishop of Bangor agreed upon by Henry I and Gruffudd ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan ( 1137), sometimes written as Gruffydd ap Cynan, was King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to Norman rule, and was remembe ...

, was consecrated at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

; on 16 January 1121, when Richard de Capella

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

was consecrated Bishop of Hereford

The Bishop of Hereford is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Hereford in the Province of Canterbury.

The episcopal see is centred in the Hereford, City of Hereford where the bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is in the Hereford Cathedr ...

at Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

; and on 2 October that year, in the same church, when Gregory or Gréne was consecrated Bishop of Dublin

The Archbishop of Dublin is an archepiscopal title which takes its name after Dublin, Ireland. Since the Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church and the other in the Church of Irelan ...

. On 6 February 1123 he was prevented by paralysis from officiating when his protégé William de Corbeil

William de Corbeil or William of Corbeil (21 November 1136) was a medieval Archbishop of Canterbury. Very little is known of William's early life or his family, except that he was born at Corbeil, south of Paris, and that he had two brothers. Ed ...

was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury.

William de Corbeil or Curboil had been for some years the Prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

of St Osyth's Priory, an Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

house founded by Richard at the village of Chich

St Osyth is an English village and civil parish in the Tendring District of north-east Essex, about west of Clacton-on-Sea and south-east of Colchester. It lies on the B1027, Colchester–Clacton road. The village is named after Osgyth, a 7t ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. The king confirmed Richard's grant of the manor to the priory around 1117-9. The priory was dedicated to a legendary Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

nun and martyr. It was only one of his great building projects, although important to him personally and intended to provide a mausoleum and chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

for himself. The rebuilding of St Paul's was a much bigger project he inherited with the see of London from Maurice, his predecessor, as the previous building had been destroyed by fire. Ordericus Vitalis portrays his efforts as enthusiastic and determined, very nearly bringing the work to completion. This was possibly true initially. However, William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a ...

believed that Maurice had committed the diocese to a scheme that was too ambitious and that Richard was damaged not only in wealth but in mental health by the enormity of the task, ultimately despairing of the burden. Nevertheless he is celebrated as the founder of St Paul's Cathedral School

(''By Faith and By Learning'')

, established =

, closed =

, type = Independent preparatory schoolChoral foundation school

, religious_affiliation = Church of England

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, hea ...

, which was to provide an education for its choristers in the succeeding centuries, slowly evolving into distinct choral and grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

s.

Richard was the recipient of significant small tokens of royal favour. Probably in 1114 the king notified Hugh de Bocland

Hugh de Bocland or Hugh of Buckland (died 1119?), was sheriff of Berkshire and several other counties.

Origins

Bocland received his surname from the manor of Buckland, near Faringdon, in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire), of which he was tenant und ...

that Richard was henceforth to receive the tithe of venison

Venison originally meant the meat of a game animal but now refers primarily to the meat of antlered ungulates such as elk or deer (or antelope in South Africa). Venison can be used to refer to any part of the animal, so long as it is edible, in ...

from Essex that had previously been a royal prerogative. Rather later was a grant to Richard and his cathedral of “the whole of the great fish caught on their land, except the tongue, which he reserves for himself.” Apparently this referred to porpoises.

Welsh affairs

/ref> The imprisonment of Iorwerth had left a partial power vacuum in

Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

, which his brother Cadwgan ap Bleddyn

Cadwgan ap Bleddyn (1051–1111) was a prince of the Kingdom of Powys ( cy, Teyrnas Powys) in north eastern Wales.

Cadwgan (possibly born 1060) was the second son of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn who was king of both Kingdom of Powys and Gwynedd.

The Anglo ...

was unable to fill. Initially these were precipitated by Owain ap Cadwgan

Owain ap Cadwgan (died 1116) was a prince of Powys in eastern Wales. He is best known for his abduction of Nest, wife of Gerald of Windsor.

Owain was the eldest son of Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, prince of part of Powys. He is first recorded in 1106, when ...

's abduction of Nest ferch Rhys

Nest ferch Rhys (c. 1085 – c. 1136) was the daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr, last King of Deheubarth in Wales, by his wife, Gwladys ferch Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn of Powys. Her family is of the House of Dinefwr. Nest was the wife of Gerald de Windsor (c. ...

in 1109, which had profound repercussions across Wales, as she was both the wife of Gerald de Windsor

Gerald de Windsor (1075 – 1135), ''alias'' Gerald FitzWalter, was an Anglo-Normans, Anglo-Norman lord who was the first Castellan of Pembroke Castle in Pembrokeshire (formerly part of the Kingdom of Deheubarth). Son of the first Constable of Wi ...

, the most powerful Norman baron in South Wales and the daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr

Rhys ap Tewdwr (c. 1040 – 1093) was a king of Deheubarth in Wales and member of the Dinefwr dynasty, a branch descended from Rhodri the Great. He was born in the area which is now Carmarthenshire and died at the battle of Brecon in April 10 ...

, the last Welsh ruler of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House of ...

. The widespread sense of outrage created a coalition of Welsh leaders against Owain and Cadygan. Richard was able to use this groundswell to send his forces and their allies across Central Wales, driving Owain and Cadwgan back into Ceredigion

Ceredigion ( , , ) is a county in the west of Wales, corresponding to the historic county of Cardiganshire. During the second half of the first millennium Ceredigion was a minor kingdom. It has been administered as a county since 1282. Cere ...

, then further into exile in Ireland. Richard partitioned the fugitives' land among his allies and in 1110 Iorwerth was released from seven years' captivity to create a new centre of power and authority.

However, Richard ordered one of his allies, Madog ap Rhiryd, to surrender some English criminals whom he was sheltering, alienating him from the new order. When Owain returned from exile, Madog immediately defected to his side and accompanied him in pillaging along the border. This led to hostilities with Iorwerth, who kept his bargain with Richard and the king, driving the outlaws from his realms. However, Owain continued his depredations from further west and Madog returned to corner and kill Iorwerth, driving him at spear-point into his blazing home. Richard dealt with each disaster by restoring relations with the perpetrators. Initially he reinstated Cadwgan in power, accepting Owain's return. When Madog murdered Cadwgan, Richard responded by granting substantial lands to him. Owain seems to have sidestepped the local conflict by making contact with the king personally.Eyton, Volume 2, p.197/ref> Succeeding his father in Powys, he was able in 1113 to blind Madog in revenge for his father's murder and to survive a full-scale royal invasion in the following year. Eyton comments on Richard's part in these events: “The grossest treachery seems to have pervaded this part of his policy.”

Death

Richard seems to have given up his political functions in his last years. Eyton thought it likely he retired to his Priory of St Osyth in Essex. Certainly he died there. On his deathbed, Richard confessed that he had lied about his tenure of a manor, previously testifying that he held it in fee, when in reality he had it under a lease.Crouch "Troubled Deathbeds" ''Albion'' p. 34 This was the manor of Betton in Berrington, to the south of Shrewsbury, which had been given toShrewsbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Shrewsbury (commonly known as Shrewsbury Abbey) is an ancient foundation in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was founded in 1083 as a Benedictine monastery by the Norm ...

soon after its foundation by Robert de Limesey __NOTOC__

Robert de Limesey (died 1117) was a medieval cleric. He became Bishop of Chester in 1085, then his title changed to Bishop of Coventry when the see was moved in 1102.Fryde, et al. ''Handbook of British Chronology'' p. 253

Robert was a ...

, then Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the C ...

Richard cleared up the matter through his confessors: William de Mareni, his own nephew and Dean of St Paul's, and Fulk, the prior of St Osyth's.Eyton, Volume 2, p.200/ref> Fulk clarified the situation in letters to the king, the Archbishop and other notables. Although Richard directed that the estate be restored to the abbey, its status was contested by his successors for decades: by Philip de Belmeis in 1127, although he quickly defaulted;Eyton, Volume 2, p.201

/ref> a few decades later by his younger son, Ranulph, who ultimately recognised the abbey's rights in return for acceptance into its fraternity; in 1212 by Roger de la Zouche, who continued his suit for years unsuccessfully. Richard also restored to the abbey the

advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of the churches at Donington and Tong: these too were to be contested in the future.

Richard died in 1127, with his death being commemorated on 16 January, so he probably died on that date. He was buried at the Priory of St Osyth. His epitaph, on a marble tomb, read:

Family

Archdeacon of London

The Archdeacon of London is a senior ecclesiastical officer in the Church of England. They are responsible for the eastern Archdeaconry (the Archdeaconry of London) of the Two Cities (London and Westminster) in the Diocese of London, an area with ...

.

However, his nephews, heirs who could be legally acknowledged, were recipients of much greater benefits. The sons of two sisters, Ralph de Langford and William de Mareni, both pursued distinguished careers in the Diocese of London and in turn became Dean of St Paul's

The dean of St Paul's is a member of, and chair of the Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral in London in the Church of England. The dean of St Paul's is also ''ex officio'' dean of the Order of the British Empire.

The current dean is Andrew Tremlett, ...

. Sons of his brother Robert received still more. Philip became his secular heir in the Midlands, receiving the substantial and lucrative estates at Tong and Donington. Philip's younger brother, Richard de Belmeis II received a royal grant of his prebends of St Alkmund's church, Shrewsbury, and the pair were able to found and endow another great Augustinian house: Lilleshall Abbey

Lilleshall Abbey was an Augustinian abbey in Shropshire, England, today located north of Telford. It was founded between 1145 and 1148 and followed the austere customs and observance of the Abbey of Arrouaise in northern France. It suffered f ...

in Shropshire. However, both Philip's sons died young, after successively inheriting the estates, which then passed through their sister Adelicia and her husband, Alan de la Zouche, to the Barons Zouche

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

. Richard later became Bishop of London. Richard Ruffus, their brother, apparently sharing his uncle's complexion, was archdeacon of Essex

The Archdeacon of West Ham is a senior ecclesiastical officer – in charge of the Archdeaconry of West Ham – in the Church of England Diocese of Chelmsford. The current archdeacon is Elwin Cockett.

Brief history

Historically, the Archdeaconry ...

in the diocese of London, and had two sons who were canons of St Paul's. Another brother, Robert seems to have been the ancestor of the later Belmeis landowning dynasty. His son, William, was a canon of St Paul's and prebendary of St Pancras, but it is unclear whether he or a brother was Robert's temporal heir.

Family tree

Based on genealogy given by Eyton, corrected and supplemented by reference to ''Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae''./ref>

Citations

References

* Crouch, David ''The Reign of King Stephen: 1135–1154'' Harlow, Essex: Longman Pearson 2000 * * Eyton, Robert William (1854–60). ''The Antiquities of Shropshire'', John Russell Smith, London, accessed 18 December 2014 atInternet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

.Volume 1 (1854)

*Forester, Thomas (1854)

''The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy by Ordericus Vitalis, Volume 3''

Bohn, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B. (Editors); Angold, M. J.; Baugh, G. C.; Chibnall, Marjorie M.; Cox, D. C.; Price, D. T. W.; Tomlinson, Margaret; Trinder, B. S.; (1973)

''A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2''

Institute of Historical Research, accessed 9 December 2014. *Greenway, Diana (editor) (1968)

''Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300: Volume 1, St. Paul's, London''

Institute of Historical Research, London, accessed 18 December 2014. * *Johnson, Charles and Cronne, H.A. (eds) (1956)

''Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, Volume 2''

Oxford, accessed 23 January 2015 at Internet Archive. * Lloyd, John Edward (1912)

A History of Wales from Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Volume 2

2nd edition, Longmans, Green, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * Owen, Hugh and Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825)

''A History of Shrewsbury, Volume 2''

Harding and Lepard, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * Page, William and Round, J Horace (1907)

''A History of the County of Essex: Volume 2''

, Institute of Historical Research, accessed 5 January 2015. *Palmer, John, and Slater, George

''Domesday Book Shropshire''

accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * *Poole, Austin Lane (1951). ''From Domeday Book to Magna Carta'', Oxford. *Rule, Martin (editor) (1884)

''Eadmeri Historia Novorum in Anglia''

Longman, London, accessed 18 December 2014 at Internet Archive. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Belmeis I, Richard de Bishops of London 1127 deaths Year of birth missing Anglo-Normans 12th-century English Roman Catholic bishops Politicians from Shropshire People from Tendring (district) Anglo-Normans in Wales Clergy from Shropshire