Richard Carrington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Christopher Carrington (26 May 1826 – 27 November 1875) was an English

In June 1852 he fixed upon a site for an observatory and dwelling-house at

In June 1852 he fixed upon a site for an observatory and dwelling-house at

On 1 September 1859, Carrington and Richard Hodgson, another English amateur astronomer, independently made the first observations of a

On 1 September 1859, Carrington and Richard Hodgson, another English amateur astronomer, independently made the first observations of a

Richard Christopher Carrington (1826–1875)

(short biographical sketch), Groupe d'Astrophysique de l'Université de Montréal (University of Montreal), 27 December 2001.

"Carrington's star billing"

an article i

The Times Literary Supplement

by John North, 24 October 2007 *

* ttp://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-abs_connect?db_key=AST&author=carrington,%20r.&aut_syn=NO R. Carrington@

amateur astronomer

Amateur astronomy is a hobby where participants enjoy observing or imaging celestial objects in the sky using the unaided eye, binoculars, or telescopes. Even though scientific research may not be their primary goal, some amateur astronomers m ...

whose 1859 astronomical observation

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical m ...

s demonstrated the existence of solar flare

A solar flare is an intense localized eruption of electromagnetic radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. Flares occur in active regions and are often, but not always, accompanied by coronal mass ejections, solar particle events, and other solar phe ...

s as well as suggesting their electrical influence upon the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

and its aurorae

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in polar regions of Earth, high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display ...

; and whose 1863 records of sunspot

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. Sun ...

observations revealed the differential rotation

Differential rotation is seen when different parts of a rotating object move with different angular velocities (rates of rotation) at different latitudes and/or depths of the body and/or in time. This indicates that the object is not solid. In fl ...

of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

.

Life

Carrington was born atChelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

, the second son of Richard Carrington, the proprietor of a large brewery at Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings whi ...

, and his wife Esther Clarke Aplin.

He entered Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, in 1844; but, though destined for the church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chris ...

, rather by his father's than by his own desire, his scientific tendencies gradually prevailed, and received a final impulse towards practical astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

from Professor Challis's lectures on the subject. This change in the purpose of his life was unopposed, and he had the prospect of ample means; so that it was purely with the object of gaining experience that he applied, shortly after taking his degree as thirty-sixth wrangler in 1848, for the post of observer in the University of Durham

Durham University (legally the University of Durham) is a collegiate university, collegiate public university, public research university in Durham, England, Durham, England, founded by an Act of Parliament in 1832 and incorporated by royal charte ...

. He entered upon his duties there in October 1849, but soon became dissatisfied with their narrow scope. The observatory was ill supplied with instruments, and the leisure left him for study served only to widen his aims. Friedrich Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the sun to another star by the method ...

's and Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander

Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander (22 March 1799 – 17 February 1875) was a German astronomer. He is known for his determinations of stellar brightnesses, positions, and distances.

Life and work

Argelander was born in Memel in the Kingd ...

's star-zones, above all, struck him as a model for imitation, and he resolved to complete by extending them to the pole. Desirous of advancing so far beyond his predecessors as to include in his survey stars of the tenth magnitude, he vainly applied for a suitable instrument, and at last, hopeless of accomplishing any part of his design at Durham, or of benefiting by any further stay, he resigned his position there in March 1852. He had not, however, been idle. Some of his observations, especially of minor planets and comets, made with a Fraunhofer equatorial Equatorial may refer to something related to:

*Earth's equator

**the tropics, the Earth's equatorial region

**tropical climate

*the Celestial equator

** equatorial orbit

**equatorial coordinate system

** equatorial mount, of telescopes

* equatorial ...

of 6½ inches aperture, had been published, in a provisional state, in the ‘Monthly Notices’ and ‘Astronomische Nachrichten,’ and the whole were definitively embodied in a volume entitled ‘Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Observatory of the University, Durham, from October 1849 to April 1852’ (Durham, 1855). His admission as a member of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

(RAS), 14 March 1851, conveyed a prompt recognition of his exceptional merits as an observer.

In June 1852 he fixed upon a site for an observatory and dwelling-house at

In June 1852 he fixed upon a site for an observatory and dwelling-house at Redhill, Surrey

Redhill () is a town in the borough of Reigate and Banstead within the county of Surrey, England. The town, which adjoins the town of Reigate to the west, is due south of Croydon in Greater London, and is part of the London commuter belt. The ...

. In July 1853 a transit-circle of 5½ feet focus, reduced in scale from the Greenwich model, and an equatorial of 4½ inches aperture, both by Simms, were in their places, and work was begun. On 9 December 1853, Carrington presented to the RAS, as the result of a preliminary survey, printed copies of nine draft maps, containing all stars down to the eleventh magnitude within 9° of the Pole (Monthly Notices, xiv. 40). Three years' steady pursuance of the adopted plan produced, in 1857, ‘A Catalogue of 3,735 Circumpolar Stars

A circumpolar star is a star that, as viewed from a given latitude on Earth, never sets below the horizon due to its apparent proximity to one of the celestial poles. Circumpolar stars are therefore visible from said location toward the nearest ...

observed at Redhill in the years 1854, 1855, and 1856, and reduced to Mean Positions for 1855.’ The work was printed at public expense, the decision to that effect by the Lords of the Admiralty rendering unnecessary the acceptance of Leverrier's handsome offer to include it in the next forthcoming volume of the ‘Annales’ of the Paris observatory. It was rewarded with the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

, in presenting which, 11 February 1859, Mr. Main dwelt upon the eminent utility of the design, as well as the ‘standard excellence’ of its execution (ib. xix. 162). It included a laborious comparison of Schwerd's places for 680 stars with those obtained at Redhill, and an elaborate dissertation on the whole theory of corrections as applied to stars near the pole. Ten corresponding maps, copper-engraved, accompanied the catalogue.

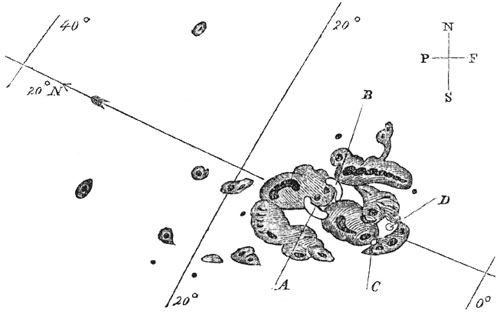

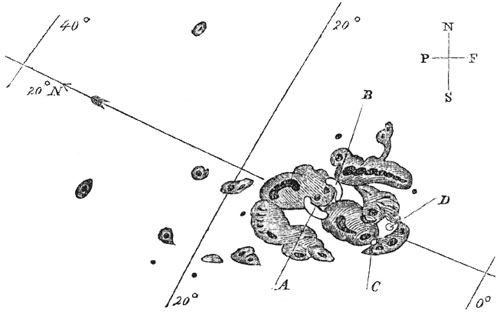

Meanwhile, Carrington had adopted, and was cultivating with his usual felicity of treatment, a ‘second subject’ at that juncture of peculiar interest and importance. While his new observatory was in course of construction, he devoted some of his spare time to examining the drawings and records of sun-spots in possession of the RAS, and was much struck with the need and scarcity of systematic solar observations. Sabine's and Wolf's discovery of the coincidence between the magnetic and sunspot periods had just then been announced, and he believed he should be able to take advantage of the pre-occupation or inability of other observers to appropriate to himself, by ‘close and methodical research,’ the next ensuing eleven-year cycle. He accordingly resolved to devote his daylight energies to the sun, while reserving his nights for the stars. Solar physics as a whole, however, he prudently excluded from his field of view. He limited his task to fixing the true period of the sun's rotation (of which curiously discrepant values had been obtained), to tracing the laws of distribution of maculæ, and investigating the existence of permanent surface-currents. Adequately to compass these ends, new devices of observation, reduction, and comparison were required. Leaving photography to his successors as too undeveloped for immediate use, he chose a method founded on the idea of making the solar disc its own circular micrometer. An image of the sun was thrown upon a screen placed at such a distance from the eyepiece of the 4½-inch equatorial as to give to the disc a diameter of 12 to 14 inches. In the focus of the telescope, which was firmly clamped, two bars of flattened gold wire were fastened at right angles to each other, and inclined about 45° on either side of the meridian. Then, as the inverted image traversed the screen, the instants of contact with the wires of the sun's limbs and of the spot-nucleus to be measured were severally noted, when an easy calculation gave its heliocentric position (ib. xiv. 153).

In this manner, during seven and a half years, 5,290 observations were made of 954 separate groups, many of which were besides accurately depicted in drawings. By the sudden death of his father, however, in July 1858, and the consequent devolution upon Carrington of the management of the brewery, the complete execution of his project of research was frustrated. He continued for some time to supervise the solar work he had previously carried on in person; but in March 1861, seeing no prospect of release from commercial engagements, he thought it advisable to close the series. The results appeared in a quarto volume, the publication of which was aided by a grant from the Royal Society. Its title ran as follows: ''Observations of the Spots on the Sun from November 9, 1853, to March 24, 1861, made at Redhill'' (London, 1863). Never were data more opportunely furnished. Perhaps more effectually than the pronouncements of spectrum analysis, they served to revolutionise ideas on solar physics.

Efforts to ascertain the true rate of solar rotation had been continually baffled by what were called the ‘proper motions’ of the spots serving as indexes to it. Carrington showed that these were in reality due to a great ‘bodily drift’ of the photosphere, diminishing apparently from the equator to the poles (ib. xix. 81). There was, then, no single period ascertainable through observations of the solar surface. By equatorial spots the circuit was found to be performed in about two and a half days less than by spots at the (ordinarily) extreme north and south limits of 45°. The assumed ‘mean period’ of 25.38 solar days applied, in fact, only to two zones 14° from the equator; nearer to it the time of rotation was shorter, further from it longer, than the average. Carrington succeeded in representing the daily movement of a spot in any heliographical latitude l, by the empirical expression 865′ ± 165 . sin 7/4 (l – 1°). But he attempted no explanation of the phenomenon. It formed, however, the basis of Faye's theory (1865) of the sun as a gaseous body ploughed through by vertical currents, which finally superseded Herschel's idea of a flame-enveloped, but cool, dark, and even habitable globe.

Carrington's determinations of the elements of the sun's rotation are still of standard authority. The inclination of the solar equator to the plane of the ecliptic he fixed at 7° 15′; the longitude of the ascending node at 73° 40′ (both for 1850) . A peculiarity in the distribution of sun-spots detected by him about the time of the minimum of 1856, afforded, as he said, ‘an instructive instance of the regular irregularity and the irregular regularity’ characterising solar phenomena (ib. xix. 1). As the minimum approached, the belts of disturbance gradually contracted towards and died out near the equator; shortly after which two fresh series broke out, as if by a completely new impulse, in comparatively high latitudes, and spread equatorially. No satisfactory rationale of this curious procedure has yet been arrived at. It is, nevertheless, intimately related to the course of sun-spot development, since Wolf found evidence of a similar behaviour in Böhm's observations of 1833–6, and it was perceived by Spörer and Secchi to recur in 1867.

While still in his apprenticeship at Durham, Carrington repaired to Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

on the occasion of the total solar eclipse of 28 July 1851, and made at Lilla Edet

Lilla Edet is a locality and the seat of Lilla Edet Municipality in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. It had 4,862 inhabitants in 2010.

Lilla Edet was the smallest of three settlements that were burnt down in Sweden on 25 June 1888. The wooden to ...

, on the Göta river, observations printed in the ''Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

'' (xxi. 58). The experience thus gained was turned to public account in the compilation of ''Information and Suggestions addressed to Persons who may be able to place themselves within the Shadow of the Total Eclipse of the Sun on September 7, 1858'', a brochure printed and circulated by the lords of the admiralty in May 1858. The eclipse to which it referred was visible in South America. A visit to the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

in 1856 gave him the opportunity of drawing up a valuable report on the condition of a number of German observatories (Monthly Notices, xvii. 43), and of visiting Schwabe at Dessau

Dessau is a town and former municipality in Germany at the confluence of the rivers Mulde and Elbe, in the '' Bundesland'' (Federal State) of Saxony-Anhalt. Since 1 July 2007, it has been part of the newly created municipality of Dessau-Roßlau ...

, to whose merits he drew explicit attention, and to whom, in the following year, he had the pleasure of transmitting the Gold Medal of the RAS. He fulfilled with great diligence the duties of secretary to that body, 1857–62, and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society on 7 June 1860.

The great solar storm of 1859

Carrington, together with fellow amateur Mr. Hodgson, were the sole witness of the extraordinary solar outburst of 1 September 1859. Carrington and Hodgson compiled independent reports which were published side by side in the ''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'' (MNRAS) is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering research in astronomy and astrophysics. It has been in continuous existence since 1827 and publishes letters and papers reporting orig ...

'', and exhibited their drawings of the event at the November 1859 meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

.

The geomagnetic solar flare hit the Earth the following days, the main body of which fell over the American continents. In these early days of electrical communication, the telegraph systems was the most affected. Lines all over Europe and North America failed, in some cases giving telegraph operators electric shock

Electrical injury is a physiological reaction caused by electric current passing through the body. The injury depends on the density of the current, tissue resistance and duration of contact. Very small currents may be imperceptible or produce ...

s.

Telegraph pylons threw sparks.

Some telegraph operators could continue to send and receive messages despite having disconnected their power supplies. Based on Carrington's observation of the solar storm, this type of event now bear the name Carrington Event

The Carrington Event was the most intense geomagnetic storm in recorded history, peaking from 1 to 2 September 1859 during solar cycle 10. It created strong auroral displays that were reported globally and caused sparking and even fires in mult ...

.

Late life and demise

But the lease by which he held his powers of useful work was unhappily running out. A severe attack of illness in 1865 left his health permanently impaired. In 1869, he married Rosa Ellen Jeffries (1845–75), and, having disposed of the brewery, he retired toChurt

Churt is a village and civil parish in the borough of Waverley, Surrey, Waverley in Surrey, England, about south of the town of Farnham on the A287 road towards Hindhead. A nucleated village, clustered settlement is set in areas acting as its b ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, where, on the top of an isolated conical hill, 60 feet high, locally known as the Middle Devil's Jump, in a lonely and picturesque spot, he built a new observatory (ib. xxx. 43). Its chief instrument was a large altazimuth on Steinheil's principle, but there are no records of observations made with it. He no longer attended the meetings of the RAS, and his last communication to it, 10 January 1873, was on the subject of a ‘double altazimuth’ of great size which he had thoughts of erecting (ib. xxxiii. 118).

A deplorable tragedy, however, supervened. On the morning of 17 November 1875 his wife was found dead in her bed, as it seemed, through an overdose of chloral

Chloral, also known as trichloroacetaldehyde or trichloroethanal, is the organic compound with the formula Cl3CCHO. This aldehyde is a colourless oily liquid that is soluble in a wide range of solvents. It reacts with water to form chloral hydrate ...

. The event, combined perhaps with the censure on a supposed deficiency of proper nursing precautions conveyed by the verdict of the coroner's jury, told heavily on her husband's spirits. He left his house on the day of the inquest, and returned to it after a week's absence, only to find it deserted by his servants. He was seen to enter it on 27 November, but was never again seen alive. After a time some neighbour gave the alarm, the doors were broken open, and his dead body was found extended on a mattress locked into a remote apartment. A poultice of tea-leaves was tied over the left ear, as if for the relief of pain, and a post-mortem examination showed death to have resulted from an effusion of blood on the brain. A verdict of ‘sudden death from natural causes’ was returned.

Legacy

Carrington's manuscript books of sun-spot observations and reductions, with a folio volume of drawings, were purchased after his death by Lord Lindsay (laterEarl of Crawford

Earl of Crawford is one of the most ancient extant titles in Great Britain, having been created in the Peerage of Scotland for Sir David Lindsay in 1398. It is the premier earldom recorded on the Union Roll.

Early history

Sir David Lindsay, who ...

), and presented to the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

(ib. xxxvi. 249). To the same body Carrington bequeathed a sum of £2,000. Among his numerous contributions to scientific collections may be mentioned a paper ‘On the Distribution of the Perihelia of the Parabolic and Hyperbolic Comets in relation to the Motion of the Solar System in Space,’ read before the Astronomical Society, 14 December 1860 (Mem. R. A. Soc. xxix. 355). The result, like that of Mohn's contemporaneous investigation, proved negative, and was thought to be, through uncontrolled conditions, nugatory; yet it perhaps conveyed an important truth as to the original connection of comets with the solar system.

Work

Even though he did not discover the 11-year sunspot activity cycle, Carrington's observations of sunspot activity after he heard aboutHeinrich Schwabe

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe (25 October 1789 – 11 April 1875) a German astronomer remembered for his work on sunspots.

Schwabe was born at Dessau. At first an apothecary, he turned his attention to astronomy, and in 1826 commenced his observations ...

's work led to the numbering of the cycles with Carrington's name. For example, the sunspot maximum of 2002 was Carrington Cycle No. 23.

Carrington also determined the elements of the rotation axis of the Sun, based on sunspot motions, and his results remain in use today. Carrington rotation is a system for measuring solar longitude based on his observations of the low-latitude solar rotation rate.

Carrington made the initial observations leading to the establishment of Spörer's law

Spörer's law predicts the variation of sunspot latitudes during a solar cycle. It was discovered by the English astronomer Richard Christopher Carrington around 1861. Carrington's work was refined by the German astronomer Gustav Spörer.

At the ...

.

Carrington won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

(RAS) in 1859.

Carrington also won the Lalande Prize

The Lalande Prize (French: ''Prix Lalande'' also known as Lalande Medal) was an award for scientific advances in astronomy, given from 1802 until 1970 by the French Academy of Sciences.

The prize was endowed by astronomer Jérôme Lalande in 180 ...

of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

in 1864, for his ''Observations of Spots on the Sun from 9 November 1853 to 24 March 1861, Made at Redhill''. This award was not reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'' (MNRAS) is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering research in astronomy and astrophysics. It has been in continuous existence since 1827 and publishes letters and papers reporting orig ...

, probably due to Carrington's bitter, acrimonious and public criticism of Cambridge University over the appointment of John Couch Adams

John Couch Adams (; 5 June 1819 – 21 January 1892) was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of ...

, Lowndean Professor of Astronomy and Geometry, as the non-observing Director of the Cambridge Observatory. As a measure of displeasure Carrington withdrew ''Observations'' from official considerations of the RAS

Ras or RAS may refer to:

Arts and media

* RAS Records Real Authentic Sound, a reggae record label

* Rundfunk Anstalt Südtirol, a south Tyrolese public broadcasting service

* Rás 1, an Icelandic radio station

* Rás 2, an Icelandic radio stati ...

for what would likely have been the book's second gold medal, for the year 1865.

Carrington super flare

On 1 September 1859, Carrington and Richard Hodgson, another English amateur astronomer, independently made the first observations of a

On 1 September 1859, Carrington and Richard Hodgson, another English amateur astronomer, independently made the first observations of a solar flare

A solar flare is an intense localized eruption of electromagnetic radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. Flares occur in active regions and are often, but not always, accompanied by coronal mass ejections, solar particle events, and other solar phe ...

. Because of a simultaneous "crochet" observed in the Kew Observatory

The King's Observatory (called for many years the Kew Observatory) is a Grade I listed building in Richmond, London. Now a private dwelling, it formerly housed an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory founded by King George III. T ...

magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, o ...

record by Balfour Stewart

Balfour Stewart (1 November 182819 December 1887) was a Scottish physicist and meteorologist.

His studies in the field of radiant heat led to him receiving the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1868. In 1859 he was appointed director of K ...

and a geomagnetic storm

A geomagnetic storm, also known as a magnetic storm, is a temporary disturbance of the Earth's magnetosphere caused by a solar wind shock wave and/or cloud of magnetic field that interacts with the Earth's magnetic field.

The disturbance that d ...

observed the following day, Carrington suspected a solar-terrestrial connection. For this reason, the geomagnetic storm of 1859 is often called the Carrington Event

The Carrington Event was the most intense geomagnetic storm in recorded history, peaking from 1 to 2 September 1859 during solar cycle 10. It created strong auroral displays that were reported globally and caused sparking and even fires in mult ...

.

Worldwide reports on the effects of the geomagnetic storm of 1859 were compiled and published by Elias Loomis

Elias Loomis (August 7, 1811 – August 15, 1889) was an American mathematician. He served as a professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Case Western Reserve University, Western Reserve College (now Case Western Reserve University), the ...

which supported the observations of Carrington and Balfour Stewart

Balfour Stewart (1 November 182819 December 1887) was a Scottish physicist and meteorologist.

His studies in the field of radiant heat led to him receiving the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1868. In 1859 he was appointed director of K ...

.

Selected writings

* * * *References

*Further reading

* – Originally published in the July 1960 issue of ''Sky & Telescope'' * * * * * – an obituary * Charbonneau, PaulRichard Christopher Carrington (1826–1875)

(short biographical sketch), Groupe d'Astrophysique de l'Université de Montréal (University of Montreal), 27 December 2001.

External links

"Carrington's star billing"

an article i

The Times Literary Supplement

by John North, 24 October 2007 *

* ttp://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-abs_connect?db_key=AST&author=carrington,%20r.&aut_syn=NO R. Carrington@

Astrophysics Data System

The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS) is an online database of over 16 million astronomy and physics papers from both peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed sources. Abstracts are available free online for almost all articles, and full scanned a ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carrington, Richard Christopher

1826 births

1875 deaths

19th-century British astronomers

Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

Fellows of the Royal Society

Burials at West Norwood Cemetery

Recipients of the Lalande Prize

Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge