Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration Of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a statement adopted by the Cabinet of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, announcing that

The southern African territory of

The southern African territory of

Believing full dominion status to be effectively symbolic and "there for the asking", Prime Minister

Believing full dominion status to be effectively symbolic and "there for the asking", Prime Minister

Smith, a farmer from the

Smith, a farmer from the  At 10 Downing Street in early September 1964, impasse developed between Douglas-Home and Smith over the best way to measure black public opinion in Southern Rhodesia. A key plank of Britain's Southern Rhodesia policy was that the terms for independence had to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole"—agreeing to this, Smith suggested that white and urban black opinion could be gauged through a general referendum of registered voters, and that rural black views could be obtained at a national '' indaba'' (tribal conference) of chiefs and headmen. Douglas-Home told Smith that although this proposal satisfied him personally, he could not accept it as he did not believe the Commonwealth, the United Nations or the Labour Party would also do so. He stressed that such a move towards accommodation with Smith might hurt the Conservatives' chances in the British general election the next month, and suggested that it might be in Smith's best interests to wait until after the election to continue negotiations. Smith accepted this argument. Douglas-Home assured Smith that a Conservative government would settle with him and grant independence within a year.

Attempting to form a viable white opposition to the Rhodesian Front, the UFP resurrected itself around Welensky, renamed itself the Rhodesia Party, and entered the Arundel and Avondale by-elections that had been called for 1 October 1964. Perturbed by the prospect of having to face the political heavyweight Welensky in parliament at the head of the opposition, the RF poured huge resources into winning both of these former UFP safe seats, and fielded

At 10 Downing Street in early September 1964, impasse developed between Douglas-Home and Smith over the best way to measure black public opinion in Southern Rhodesia. A key plank of Britain's Southern Rhodesia policy was that the terms for independence had to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole"—agreeing to this, Smith suggested that white and urban black opinion could be gauged through a general referendum of registered voters, and that rural black views could be obtained at a national '' indaba'' (tribal conference) of chiefs and headmen. Douglas-Home told Smith that although this proposal satisfied him personally, he could not accept it as he did not believe the Commonwealth, the United Nations or the Labour Party would also do so. He stressed that such a move towards accommodation with Smith might hurt the Conservatives' chances in the British general election the next month, and suggested that it might be in Smith's best interests to wait until after the election to continue negotiations. Smith accepted this argument. Douglas-Home assured Smith that a Conservative government would settle with him and grant independence within a year.

Attempting to form a viable white opposition to the Rhodesian Front, the UFP resurrected itself around Welensky, renamed itself the Rhodesia Party, and entered the Arundel and Avondale by-elections that had been called for 1 October 1964. Perturbed by the prospect of having to face the political heavyweight Welensky in parliament at the head of the opposition, the RF poured huge resources into winning both of these former UFP safe seats, and fielded

Labour defeated the Conservatives by four seats in the British

Labour defeated the Conservatives by four seats in the British

The two premiers were brought together in person in late January 1965, when Smith travelled to London for Sir Winston Churchill's funeral. Following an episode concerning Smith's non-invitation to a luncheon at Buckingham Palace after the funeral—noticing the Rhodesian's absence, the Queen sent a royal

The two premiers were brought together in person in late January 1965, when Smith travelled to London for Sir Winston Churchill's funeral. Following an episode concerning Smith's non-invitation to a luncheon at Buckingham Palace after the funeral—noticing the Rhodesian's absence, the Queen sent a royal

The Rhodesian Minister for Justice and Law and Order, Desmond Lardner-Burke, presented the rest of the Cabinet with a draft for the declaration of independence on 5 November 1965. When Jack Howman, Minister of Tourism and Information, said that he was also preparing a draft, the Cabinet decided to wait to see his version too. The ministers agreed that if an independence proclamation were issued, they would all sign it. On 9 November, the Cabinet jointly devised an outline for the proclamation document and the accompanying statement to be made by Smith. The final version of the declaration of independence was prepared by a sub-committee of civil servants headed by Gerald Clarke, the Cabinet Secretary, with the

The Rhodesian Minister for Justice and Law and Order, Desmond Lardner-Burke, presented the rest of the Cabinet with a draft for the declaration of independence on 5 November 1965. When Jack Howman, Minister of Tourism and Information, said that he was also preparing a draft, the Cabinet decided to wait to see his version too. The ministers agreed that if an independence proclamation were issued, they would all sign it. On 9 November, the Cabinet jointly devised an outline for the proclamation document and the accompanying statement to be made by Smith. The final version of the declaration of independence was prepared by a sub-committee of civil servants headed by Gerald Clarke, the Cabinet Secretary, with the

Official diplomatic recognition by other countries was key for Rhodesia as it was the only way it could regain the international legitimacy it had lost through UDI. Recognition by the UK itself through a bilateral settlement would be the "first prize", in Smith's words, as it would end sanctions and constitutional ambiguity and make foreign acceptance, at least in the West, far more likely. Considering their country a potentially important player in the Cold War as a "bastion against communism" in southern Africa, the RF posited that some Western countries might recognise UDI even without a prior Anglo-Rhodesian rapprochement. Specifically, it expected diplomatic recognition from South Africa and Portugal, and thought that France might recognise Rhodesia to annoy Britain and create a precedent for an independent Quebec. But although South Africa and Portugal gave economic, military and limited political support to the post-UDI government (as did France and other nations, to a lesser extent), neither they nor any other country ever recognised Rhodesia as a ''de jure'' independent state. Rhodesia's unsuccessful attempts to win Western support and recognition included offers to the US government in 1966 and 1967, ignored by

Official diplomatic recognition by other countries was key for Rhodesia as it was the only way it could regain the international legitimacy it had lost through UDI. Recognition by the UK itself through a bilateral settlement would be the "first prize", in Smith's words, as it would end sanctions and constitutional ambiguity and make foreign acceptance, at least in the West, far more likely. Considering their country a potentially important player in the Cold War as a "bastion against communism" in southern Africa, the RF posited that some Western countries might recognise UDI even without a prior Anglo-Rhodesian rapprochement. Specifically, it expected diplomatic recognition from South Africa and Portugal, and thought that France might recognise Rhodesia to annoy Britain and create a precedent for an independent Quebec. But although South Africa and Portugal gave economic, military and limited political support to the post-UDI government (as did France and other nations, to a lesser extent), neither they nor any other country ever recognised Rhodesia as a ''de jure'' independent state. Rhodesia's unsuccessful attempts to win Western support and recognition included offers to the US government in 1966 and 1967, ignored by

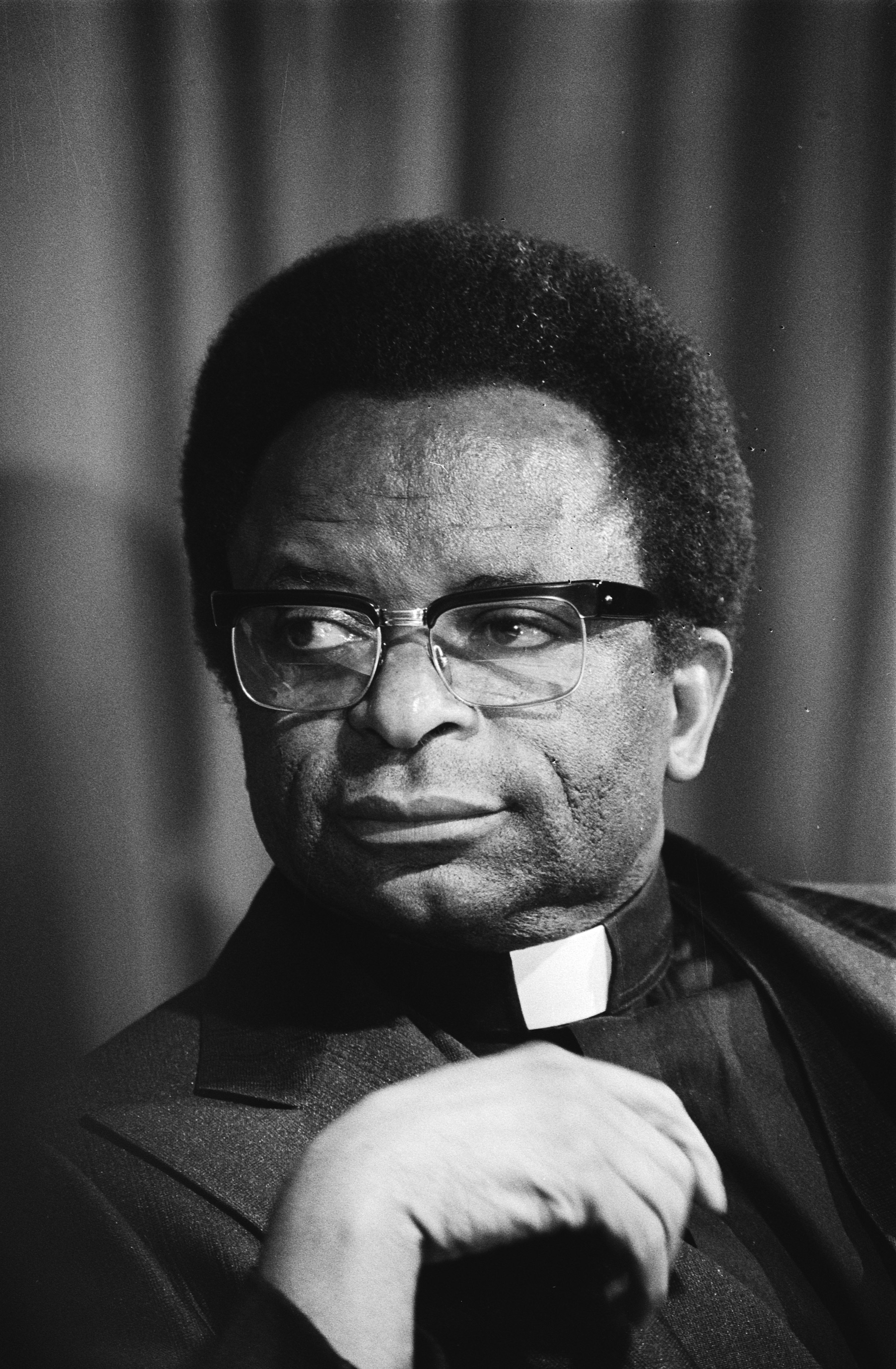

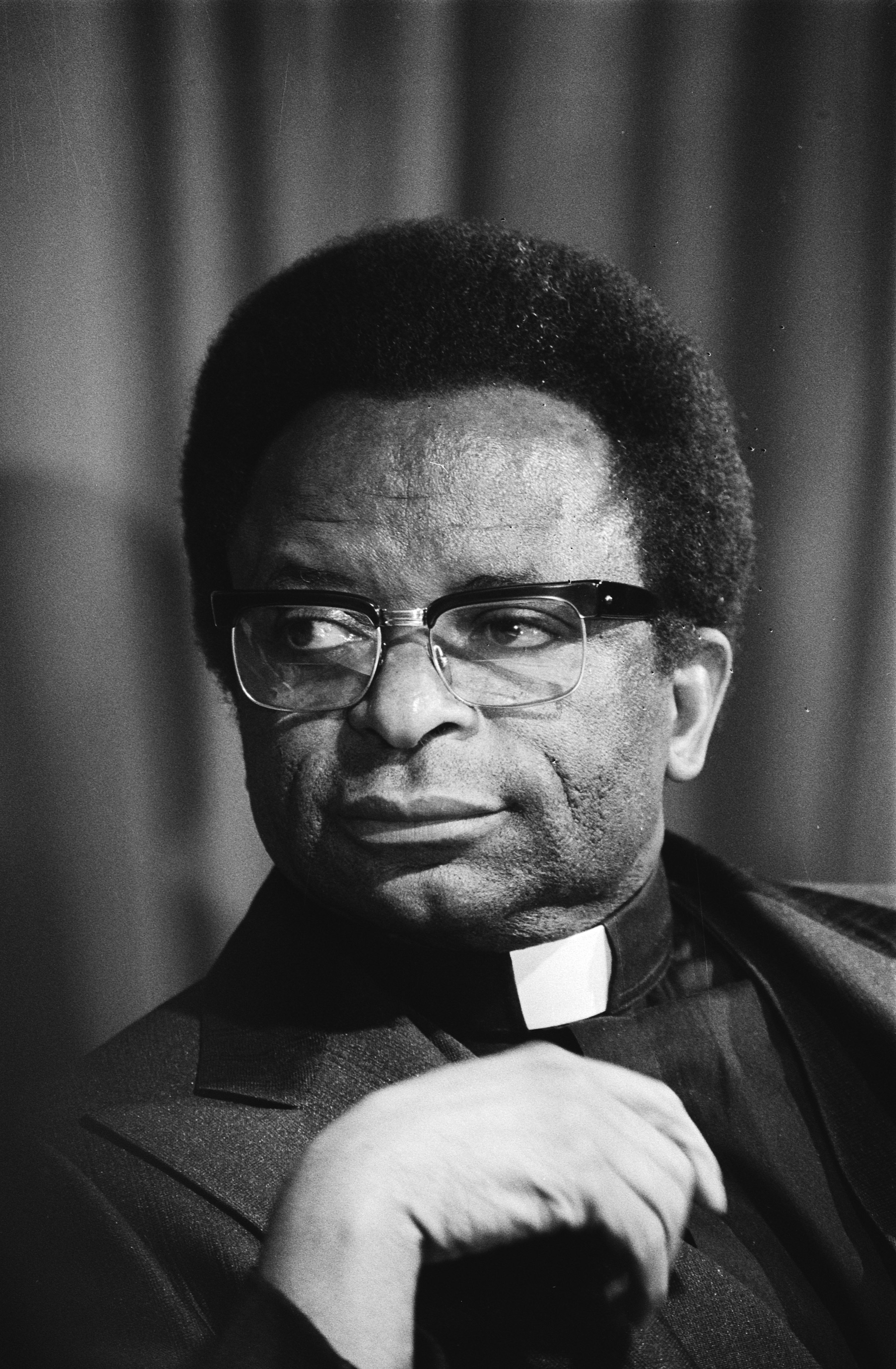

Wilson told the British House of Commons in January 1966 that he would not enter any kind of dialogue with the post-UDI Rhodesian "illegal regime" until it gave up its claim of independence, but by mid-1966 British and Rhodesian civil servants were holding "talks about talks" in London and Salisbury. By November that year, Wilson had agreed to negotiate personally with Smith. The two Prime Ministers unsuccessfully attempted to settle aboard HMS ''Tiger'' in December 1966 and HMS ''Fearless'' in October 1968. After the Conservatives returned to power in Britain in 1970, provisional agreement was reached in November 1971 between the Rhodesian government and a British team headed by Douglas-Home (who was

Wilson told the British House of Commons in January 1966 that he would not enter any kind of dialogue with the post-UDI Rhodesian "illegal regime" until it gave up its claim of independence, but by mid-1966 British and Rhodesian civil servants were holding "talks about talks" in London and Salisbury. By November that year, Wilson had agreed to negotiate personally with Smith. The two Prime Ministers unsuccessfully attempted to settle aboard HMS ''Tiger'' in December 1966 and HMS ''Fearless'' in October 1968. After the Conservatives returned to power in Britain in 1970, provisional agreement was reached in November 1971 between the Rhodesian government and a British team headed by Douglas-Home (who was

online review

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * in * * * * * * {{Wikisourcepar, Unilateral Declaration of Independence 1965 in the British Empire 1965 in international relations 1965 in law 1965 in the United Kingdom 1965 documents British Empire Cold War in Africa Cold War history of the United Kingdom

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally k ...

or simply Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

, a British territory in southern Africa that had governed itself since 1923, now regarded itself as an independent sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

. The culmination of a protracted dispute between the British and Rhodesian governments regarding the terms under which the latter could become fully independent, it was the first unilateral break from the United Kingdom by one of its colonies since the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

in 1776. The UK, the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

and the United Nations all deemed Rhodesia's UDI illegal, and economic sanctions, the first in the UN's history, were imposed on the breakaway colony. Amid near-complete international isolation, Rhodesia continued as an unrecognised state with the assistance of South Africa and (until 1974) Portugal.

The Rhodesian government, which mostly comprised members of the country's white

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

minority of about 5%, was indignant when, amid the UK colonial government's ''Wind of Change'' policies of decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

, less developed African colonies to the north without comparable experience of self-rule quickly advanced to independence during the early 1960s while Rhodesia was refused sovereignty under the newly ascendant principle of " no independence before majority rule" ("NIBMAR"). Most white Rhodesians felt that they were due independence following four decades of self-government, and that the British government was betraying them by withholding it.

A stalemate developed between the British and Rhodesian prime ministers, Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

and Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

respectively, between 1964 and 1965. The dispute largely surrounded the British condition that the terms for independence had to be acceptable "to the people of the country as a whole"; Smith contended that this was met, while the UK and African Nationalist Rhodesian leaders held that it was not. After Wilson proposed in late October 1965 that the UK might safeguard future black representation in the Rhodesian parliament by withdrawing some of the colonial government's devolved powers, then presented terms for an investigatory Royal Commission that the Rhodesians found unacceptable, Smith and his Cabinet declared independence. Calling this treasonous, the British colonial governor Governors and administrators of colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of th ...

, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, formally dismissed Smith and his government, but they ignored him and appointed an " Officer Administering the Government" to take his place.

While no country recognised the UDI, the Rhodesian High Court deemed the post-UDI government legal and ''de jure'' in 1968. The Smith administration initially professed continued loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, but abandoned this in 1970 when it declared a republic in an unsuccessful attempt to win foreign recognition. The Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three forc ...

, a guerrilla conflict between the government and two rival communist-backed black Rhodesian groups, began in earnest two years later, and after several attempts to end the war Smith concluded the Internal Settlement

The Internal Settlement was an agreement which was signed on 3 March 1978 between Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith and the moderate African nationalist leaders comprising Bishop Abel Muzorewa, Ndabaningi Sithole and Senator Chief Jeremiah Ch ...

with non-militant nationalists in 1978. Under these terms the country was reconstituted under black rule as Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, and sometimes as Rhobabwe, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June to 12 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was p ...

in June 1979, but this new order was rejected by the guerrillas and the international community. The Bush War continued until Zimbabwe Rhodesia revoked its UDI as part of the Lancaster House Agreement

The Lancaster House Agreement, signed on 21 December 1979, declared a ceasefire, ending the Rhodesian Bush War; and directly led to Rhodesia achieving internationally recognised independence as Zimbabwe. It required the full resumption of di ...

in December 1979. Following a brief period of direct British rule, the country was granted internationally recognised independence under the name Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

in 1980.

Background

Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

, officially Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally k ...

, was a unique case in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

: although a colony in name, it was internally self-governing

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority (sociology), authority. It may refer to personal co ...

and constitutionally not unlike a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

. This situation dated back to 1923, when it was granted responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bra ...

within the Empire as a self-governing colony, following three decades of administration and development by the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

. Britain had intended Southern Rhodesia's integration into the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

as a new province, but this having been rejected by registered voters in the 1922 government referendum, the territory was moulded into a prospective dominion instead. It was empowered to run its own affairs in almost all respects, including defence.

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament ...

's powers over Southern Rhodesia under the 1923 constitution were, on paper, considerable; the British Crown was theoretically able to cancel any passed bill within a year, or alter the constitution however it wished. These reserved powers were intended to protect the indigenous black Africans from discriminatory legislation and to safeguard British commercial interests in the colony, but as Claire Palley

Claire Dorothea Taylor Palley, OBE (born 17 February 1931) is a South African academic and lawyer who specialises in constitutional and human rights law. She was the first woman to hold a Chair in Law at a United Kingdom university when she was ...

comments in her constitutional history of the country, it would have been extremely difficult for Whitehall to enforce such actions, and attempting to do so would have probably caused a crisis. In the event, they were never exercised. A generally co-operative relationship developed between Whitehall and the colonial government and civil service in Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, and dispute was rare.

The 1923 constitution was drawn up in non-racial terms, and the electoral system it devised was similarly open, at least in theory. Voting qualifications regarding personal income, education and property, similar to those of the Cape Qualified Franchise

The Cape Qualified Franchise was the system of non-racial Suffrage, franchise that was adhered to in the Cape Colony, and in the Cape Province in the early years of the Union of South Africa. Qualifications for the right to vote at parliamentary ...

, were applied equally to all, but since most blacks did not meet the set standards, both the electoral roll and the colonial parliament were overwhelmingly from the white

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

minority of about 5%. The result was that black interests were sparsely represented if at all, something that most of the colony's whites showed little interest in changing; they claimed that most blacks were uninterested in Western-style political process and that they would not govern properly if they took over. Bills such as the Land Apportionment Act of 1930

The 1930 Land Apportionment Act made it illegal for Africans to purchase land outside of established Native Purchase Areas in the region of Southern Rhodesia, what is now known as Zimbabwe. Before the 1930 act, land was not openly accessible to na ...

, which earmarked about half of the country for white ownership and residence while dividing the rest into black purchase, tribal trust and national areas, were variously biased towards the white minority. White settlers and their offspring provided most of the colony's administrative, industrial, scientific and farming skills, and built a relatively balanced, partially industrialised market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ar ...

, boasting strong agricultural and manufacturing sectors, iron and steel industries and modern mining enterprises. Everyday life was marked by discrimination ranging from job reservation for whites to petty segregation of trains, post office queues and the like. Whites owned most of the best farmland, and had far superior education, wages and homes, but the schooling, healthcare, infrastructure and salaries available to black Rhodesians were nevertheless very good by African standards.

In the wider Imperial context, Southern Rhodesia occupied a category unto itself because of the "special quasi-independent status" it held. The Dominions Office

The position of Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs was a British cabinet-level position created in 1925 responsible for British relations with the Dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, and the Irish Fre ...

, formed in 1925 to handle British relations with the dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, South Africa and the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independ ...

(the Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that sets the basis for the relationship between the Commonwealth realms and the Crown.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of t ...

delineated the rights of the dominions more clearly in that year), also dealt with Southern Rhodesia, and Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

s included the Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

alongside those of the dominions from 1932. This unique arrangement continued following the advent of Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences in 1944. Southern Rhodesians of all races fought for Britain in the Second World War, and the colonial government gradually received more autonomy regarding external affairs. During the immediate post-war years, Southern Rhodesian politicians generally thought that they were as good as independent as they were, and that full autonomy in the form of dominionship would make little difference to them. Post-war immigration to Southern Rhodesia, mainly from Britain, Ireland and South Africa, caused the white community to swell from 68,954 in 1941 to 221,504 in 1961. The black population grew from 1,400,000 to 3,550,000 over the same period. Rhodesian authorities actively promoted immigration and reproduction of whites to boost their numbers while encouraging family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marita ...

for blacks to curtail their numbers. They hoped that by altering the demographic content of the territory enough they could have a stronger position from which to petition the British government for more autonomy.

Federation and the Wind of Change

Believing full dominion status to be effectively symbolic and "there for the asking", Prime Minister

Believing full dominion status to be effectively symbolic and "there for the asking", Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins

Godfrey Martin Huggins, 1st Viscount Malvern (6 July 1883 – 8 May 1971), was a Rhodesian politician and physician. He served as the fourth Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1933 to 1953 and remained in office as the first Prime Mini ...

(in office from 1933 to 1953) twice ignored British overtures hinting at dominionship, and instead pursued an initially semi-independent Federation with Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodes ...

and Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasal ...

, two colonies directly administered from London. He hoped that this might set in motion the creation of one united dominion in south-central Africa, emulating the Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Western ...

half a century before. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the B ...

, defined in its constitution as indissoluble, began in 1953, mandated by the results of a mostly white referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

, with Southern Rhodesia, the most developed of the three territories, at its head, Huggins as Federal Prime Minister and Salisbury as Federal capital.

Coming at the start of the decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

period, the Federation of self-governing Southern Rhodesia with two directly ruled British protectorates was later described by the British historian Robert Blake as "an aberration of history—a curious deviation from the inevitable course of events". The project faced black opposition from the start, and ultimately failed because of the shifting international attitudes and rising black Rhodesian ambitions of the late 1950s and early 1960s, often collectively called the Wind of Change. Britain, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

vastly accelerated their withdrawal from Africa during this period, believing colonial rule to be no longer sustainable geopolitically or ethically. The idea of " no independence before majority rule", commonly abbreviated to "NIBMAR", gained considerable ground in British political circles. When Huggins (who had been recently ennobled as Lord Malvern) asked Britain to make the Federation a dominion in 1956, he was rebuffed. The opposition Dominion Party responded by repeatedly calling for a Federal unilateral declaration of independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state which it is secedi ...

(UDI) over the next few years. Following Lord Malvern's retirement in late 1956, his successor Sir Roy Welensky pondered such a move on at least three occasions.

Attempting to advance the case for Southern Rhodesian independence, particularly in the event of Federal dissolution, the Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister Sir Edgar Whitehead brokered the 1961 constitution with Britain, which he thought would remove all British powers of reservation over Southern Rhodesian bills and acts, and put the country on the brink of full sovereignty. Despite its containing no independence guarantees, Whitehead, Welensky and other proponents of this constitution presented it to the Southern Rhodesian electorate as the "independence constitution" under which Southern Rhodesia would become a dominion on a par with Australia, Canada and New Zealand if the Federation dissolved. White dissenters included Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

, MP for Gwanda

Gwanda is a town in Zimbabwe. It is the capital of the province of Matabeleland South, one of the ten administrative provinces in the country. It is also the district capital of Gwanda District, one of the seven administrative districts in t ...

and Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

...

for the governing United Federal Party

The United Federal Party (UFP) was a political party in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

History

The UFP was formed in November 1957 by a merger of the Federal Party, which had operated at the federal level, and the Southern Rhodesian ...

(UFP) in the Federal Assembly, who took exception to the constitution's omission of an explicit promise of Southern Rhodesian independence in the event of Federal dissolution, and ultimately resigned his post in protest. A referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

of the mostly white electorate approved the new constitution by a majority of 65% on 26 July 1961. The final version of the constitution included a few extra provisions inserted by the British, one of which—Section 111—reserved full powers to the Crown to amend, add to or revoke certain sections of the Southern Rhodesian constitution by Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''Ki ...

at the request of the British government. This effectively negated the relinquishment of British powers described elsewhere in the document, but the Southern Rhodesians did not initially notice it.

The black Rhodesian movement in Southern Rhodesia, founded and organised by urban black elites during the late 1950s, was repeatedly banned by the colonial government because of the political violence, industrial sabotage and intimidation of potential black voters that characterised its campaign. The principal nationalist group, led by the Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council ...

trade unionist Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

, renamed itself with each post-ban reorganisation, and by the start of 1962 was called the Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zim ...

(ZAPU). Attempting to win black political support, Whitehead proposed a number of reforms to racially discriminatory legislation, including the Land Apportionment Act, and promised to implement these if his UFP won the next Southern Rhodesian election. But intimidation by ZAPU of prospective black voters impeded the UFP's efforts to win their support, and much of the white community saw Whitehead as too radical, and soft on what they saw as black extremism. In the December 1962 Southern Rhodesian election, the UFP was defeated by the Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front was a right-wing conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. It was the last ruling party of Southern Rhodesia prior to that country's unilateral declaration of independence, and the ru ...

(RF), a newly formed alliance of conservative voices headed by Winston Field and Ian Smith, in what was widely considered a shock result. Field became Prime Minister, with Smith as his deputy.

Federal dissolution; the roots of mistrust

Meanwhile, secessionist black Rhodesian parties won electoral victories in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, andHarold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

's Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

administration in Britain moved towards breaking up the Federation, resolving that it had become untenable. In February 1962, the British Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

The Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations was a British Cabinet minister responsible for dealing with the United Kingdom's relations with members of the Commonwealth of Nations (its former colonies). The minister's department was the Commo ...

, Duncan Sandys

Edwin Duncan Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a key r ...

, secretly informed the Nyasaland nationalist leader Hastings Banda

Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1898 – 25 November 1997) was the prime minister and later president of Malawi from 1964 to 1994 (from 1964 to 1966, Malawi was an independent Dominion / Commonwealth realm).

In 1966, the country became a republic and ...

that secession would be allowed. A few days later, he horrified Welensky by telling him that "we British have lost the will to govern". "But we haven't", retorted Julian Greenfield, Welensky's Law Minister. Macmillan's Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

and First Secretary of State

The First Secretary of State is an office that is sometimes held by a minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The office indicates seniority, including over all other Secretaries of State. The office is not always in use, ...

, R A Butler, who headed British oversight of the Federation, officially announced Nyasaland's right to secede in December 1962. Four months later, he informed the three territories that he was going to convene a conference to decide the Federation's future.

As Southern Rhodesia had been the UK's legislative partner in forming the Federation in 1953, it would be impossible (or at least very difficult) for Britain to dissolve the union without Southern Rhodesia's co-operation. Field could therefore potentially hamstring the British by refusing to attend the conference until they pledged to grant his country full independence. According to Field, Smith and other RF politicians, Butler made several such guarantees orally to ensure their co-operation at the conference, but repeatedly refused to give anything on paper. The Southern Rhodesians claimed that Butler justified his refusal to give a written promise by saying that binding Whitehall to a document rather than his word would be against the Commonwealth's "spirit of trust"—an argument that Field eventually accepted.; ; "Let's remember the trust you emphasised", Smith warned, according to Field's account wagging his finger at Butler; "if you break that you will live to regret it." Southern Rhodesia attended the conference, which was held at Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls (Lozi language, Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "The Smoke That Thunders"; Tonga language (Zambia and Zimbabwe), Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River in southern Africa, which provides hab ...

over a week starting from 28 June 1963, and among other things it was agreed to formally liquidate the Federation at the end of the year. In the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

afterwards, Butler flatly denied suggestions that he had "oiled the wheels" of Federal dissolution with secret promises to the Southern Rhodesians.

Field's government was startled by Britain's announcement in October 1963 that Nyasaland would become fully independent on 6 July 1964. While no date was set for Northern Rhodesian statehood, it was generally surmised that it was going to follow shortly thereafter. Smith was promptly sent to London, where he held a round of inconclusive Southern Rhodesian independence talks with the new British Prime Minister, Sir Alec Douglas-Home. Around the same time, the presence and significance of Section 111 of the 1961 constitution emerged in Southern Rhodesia, prompting speculation in political circles that a future British government might, if it were so inclined, go against previous conventions by legislating for Salisbury without its consent, withdrawing devolved powers or otherwise altering the Southern Rhodesian constitution. Fearing what the Labour Party might do if it won the next British general election (which was projected for late 1964), the Southern Rhodesians stepped up their efforts, hoping to win independence before Britain went to the polls, and preferably not after Nyasaland. The Federation dissolved as scheduled at the end of 1963.

Positions and motivations

British government stance

The British government's refusal to grant independence to Southern Rhodesia under the 1961 constitution was largely the result of the geopolitical and moral shifts associated with the Wind of Change, coupled with the UK's wish to avoid opprobrium and loss of prestige in the United Nations (UN) and the Commonwealth. The issue gained international attention in Africa and worldwide as a flashpoint for questions of decolonisation and racism. By the early 1960s, general consensus in the post-colonial UN—particularly theGeneral Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

, where the communist bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

and the Afro-Asian lobby were collectively very strong—roundly denounced all forms of colonialism, and supported communist-backed black nationalist insurgencies across southern Africa, regarding them as racial liberation movements. Amid the Cold War, Britain opposed the spread of Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and Chinese influence into Africa, but knew it would become an international pariah if it publicly expressed reservations or backed down on NIBMAR in the Southern Rhodesia question. Once the topic of Southern Rhodesia came to the fore in the UN and other bodies, particularly the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

(OAU), even maintaining the ''status quo'' became regarded as unacceptable internationally, causing the UK government a great deal of embarrassment.

In the Commonwealth context, too, Britain knew that simply granting independence to Southern Rhodesia was out of the question as many of the Afro-Asian countries were also Commonwealth members. Statehood for Salisbury without majority rule would split the Commonwealth and perhaps cause it to break up, a disastrous prospect for British foreign policy. The Commonwealth repeatedly called on Britain to intervene directly should Southern Rhodesian defiance continue, while liberals in Britain worried that if left unchecked Salisbury might drift towards South African-style apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

. Anxious to avoid having to choose between Southern Rhodesia and the Commonwealth, Whitehall attempted to negotiate a middle way between the two, but ultimately put international considerations first, regarding them as more important.

At party level, the Labour Party, in opposition until October 1964, was overtly against Southern Rhodesian independence under the 1961 constitution and supportive of the black Rhodesian movement on ideological and moral grounds. The Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a l ...

, holding a handful of parliament seats, took a similar stance. The Conservative Party, while also following a policy of decolonisation, was more sympathetic to the Southern Rhodesian government's position, and included members who openly supported it.

Southern Rhodesian government view

The Southern Rhodesian government found it bizarre that Britain was making independent states out of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, less developed territories with little experience of self-rule, while withholding sovereign statehood from Southern Rhodesia, the Federation's senior partner, which had already been self-governing for four decades and which was one of the most prosperous and developed countries in Africa. The principle of majority rule, the basis for this apparent inconsistency, was considered irrelevant by the Southern Rhodesians. They had presumed that in the event of Federal dissolution they would be first in line for independence without major adjustments to the 1961 constitution, an impression confirmed to them by prior intergovernmental correspondence, particularly the oral promises they claimed to have received from Butler. When it did not prove forthcoming they felt cheated. Salisbury contended that its predominantly white legislature was more deserving of independence than the untried black Rhodesian leaders as it had proven its competence over decades of self-rule. The RF claimed that the bloody civil wars, military coups and other disasters that plagued the new majority-ruled African states to the north, many of which had become corrupt, autocratic or communist one-party states very soon after independence, showed that black Rhodesian leaders were not ready to govern. Influenced strongly by the white refugees who had fled south from theCongo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

, it presented chaotic doomsday scenarios of what black Rhodesian rule in Southern Rhodesia might mean, particularly for the white community. Proponents of the RF stand downplayed black Rhodesian grievances regarding land ownership and segregation, and argued that despite the racial imbalance in domestic politics—whites made up 5% of the population, but over 90% of registered voters—the electoral system was not racist as the franchise was based on financial and educational qualifications rather than ethnicity. They emphasised the colony's proud war record on Britain's behalf, and expressed a wish in the Cold War context to form an anti-communist, pro-Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

front in Africa alongside South Africa and Portugal.

These factors combined with what RF politicians and supporters saw as British decadence, chicanery and betrayal to create the case they put forward that UDI, while dubious legally and likely to provoke international uproar, might nevertheless be in their eyes justifiable and necessary for the good of the country and region if an accommodation could not be found with Whitehall.

Road to UDI

First steps, under Field

Field's failure to secure independence concurrently with the end of the Federation caused his Cabinet's support for him to waver during late 1963 and early 1964. The RFcaucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

in January 1964 revealed widespread dissatisfaction with him on the grounds that the British seemed to be outwitting him. The Prime Minister was put under immense pressure to win the colony's independence. Field travelled to England later that month to press Douglas-Home and Sandys for independence, and raised the possibility of UDI on a few occasions, but returned empty-handed on 2 February.

The RF united behind Field after Sandys wrote him a terse letter warning him of the likely Commonwealth reaction to a declaration of independence, but the Prime Minister then lost his party's confidence by failing to pursue a possible route to at least ''de facto'' independence devised by Desmond Lardner-Burke, a lawyer and RF MP for Gwelo. During March 1964, the Legislative Assembly in Salisbury considered and passed Lardner-Burke's motion that the Governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, should submit a petition to the Queen requesting alteration of Section 111 of the 1961 constitution so that the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

described therein would be exercised at the request of the Southern Rhodesian government rather than that of its British counterpart. This would both remove the possibility of British legislative interference and pave the way for an attempted assumption of independence by Order in Council.

The RF's intention was partly to test whether or not the British would attempt to block this bill after Gibbs had granted Royal Assent to it, but this issue never came to a head because Sandys persuaded Field not to forward it to Gibbs for ratification on the grounds that it had not been unanimously passed. Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, one of Southern Rhodesia's main supporters in Britain, despaired at Field's lack of action, telling Welensky that as he saw it "the simple time to have declared independence, whether right or wrong, would have been when the Federation came to an end". The RF hierarchy interpreted this latest backtrack by Field as evidence that he would not seriously challenge the British on the independence issue, and forced his resignation on 13 April 1964. Smith accepted the Cabinet's nomination to take his place.

Smith replaces Field; talks with Douglas-Home

Smith, a farmer from the

Smith, a farmer from the Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Mercia, Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in ...

town of Selukwe

Shurugwi, formerly Selukwe, is a small town and administrative centre in Midlands Province, southern Zimbabwe, located about 350 km (220 miles) south of Harare, with a population of 22,900 according to the 2022 census. The town was establ ...

who had been seriously wounded while serving in the British Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

during the Second World War, was Southern Rhodesia's first native-born Prime Minister. Regarded in British political circles as a "raw colonial"—when he took over, Smith's personal experience of the UK comprised four brief visits—he promised a harder line than Field in independence talks.; ; The RF's replacement of Field drew criticism from the British Labour Party, whose leader Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

called it "brutal", while Nkomo described the new Smith Cabinet as "a suicide squad ... not interested in the welfare of all the people but only in their own". Smith said he was pursuing a middle course between black Rhodesian rule and apartheid so that there would still be "a place for the white man" in Southern Rhodesia; this would benefit the blacks too, he claimed. He held that the government should be based "on merit, not on colour or nationalism", and insisted that there would be "no African nationalist government here in my lifetime".

Salisbury's blunt refusal to be part of the Wind of Change caused the Southern Rhodesian military's traditional British and American suppliers to impose an informal embargo, and prompted Whitehall and Washington to stop sending Southern Rhodesia financial aid around the same time. In June 1964, Douglas-Home informed Smith that Southern Rhodesia would not be represented at the year's Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference, despite Salisbury's record of attendance going back to 1932, because of a change in policy to only include representatives from fully independent states. This decision, taken by Britain to preempt the possibility of open confrontation with Asian and black African leaders at the conference, deeply insulted Smith. Lord Malvern equated Britain's removal of Southern Rhodesia's conference seat with "kicking us out of the Commonwealth", while Welensky expressed horror at what he described as "this cavalier treatment of a country which has, since its creation, staunchly supported, in every possible way, Britain and the Commonwealth".

At 10 Downing Street in early September 1964, impasse developed between Douglas-Home and Smith over the best way to measure black public opinion in Southern Rhodesia. A key plank of Britain's Southern Rhodesia policy was that the terms for independence had to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole"—agreeing to this, Smith suggested that white and urban black opinion could be gauged through a general referendum of registered voters, and that rural black views could be obtained at a national '' indaba'' (tribal conference) of chiefs and headmen. Douglas-Home told Smith that although this proposal satisfied him personally, he could not accept it as he did not believe the Commonwealth, the United Nations or the Labour Party would also do so. He stressed that such a move towards accommodation with Smith might hurt the Conservatives' chances in the British general election the next month, and suggested that it might be in Smith's best interests to wait until after the election to continue negotiations. Smith accepted this argument. Douglas-Home assured Smith that a Conservative government would settle with him and grant independence within a year.

Attempting to form a viable white opposition to the Rhodesian Front, the UFP resurrected itself around Welensky, renamed itself the Rhodesia Party, and entered the Arundel and Avondale by-elections that had been called for 1 October 1964. Perturbed by the prospect of having to face the political heavyweight Welensky in parliament at the head of the opposition, the RF poured huge resources into winning both of these former UFP safe seats, and fielded

At 10 Downing Street in early September 1964, impasse developed between Douglas-Home and Smith over the best way to measure black public opinion in Southern Rhodesia. A key plank of Britain's Southern Rhodesia policy was that the terms for independence had to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole"—agreeing to this, Smith suggested that white and urban black opinion could be gauged through a general referendum of registered voters, and that rural black views could be obtained at a national '' indaba'' (tribal conference) of chiefs and headmen. Douglas-Home told Smith that although this proposal satisfied him personally, he could not accept it as he did not believe the Commonwealth, the United Nations or the Labour Party would also do so. He stressed that such a move towards accommodation with Smith might hurt the Conservatives' chances in the British general election the next month, and suggested that it might be in Smith's best interests to wait until after the election to continue negotiations. Smith accepted this argument. Douglas-Home assured Smith that a Conservative government would settle with him and grant independence within a year.

Attempting to form a viable white opposition to the Rhodesian Front, the UFP resurrected itself around Welensky, renamed itself the Rhodesia Party, and entered the Arundel and Avondale by-elections that had been called for 1 October 1964. Perturbed by the prospect of having to face the political heavyweight Welensky in parliament at the head of the opposition, the RF poured huge resources into winning both of these former UFP safe seats, and fielded Clifford Dupont

Clifford Walter Dupont, GCLM, ID (6 December 1905 – 28 June 1978) was a British-born Rhodesian politician who served in the internationally unrecognised positions of officer administrating the government (from 1965 until 1970) and president ( ...

, Smith's deputy, against Welensky in Arundel. The RF won both seats comfortably, and the Rhodesia Party soon faded away. Spurred on by this success, Smith organised the ''indaba'' for 22 October, and called a general independence referendum for 5 November 1964. Meanwhile, Wilson wrote a number of letters to black Southern Rhodesians, assuring them that "the Labour Party is totally opposed to granting independence to Southern Rhodesia so long as the government of that country remains under the control of the white minority".

Wilson's Labour government; Salisbury's tests of opinion

Labour defeated the Conservatives by four seats in the British

Labour defeated the Conservatives by four seats in the British general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

on 15 October 1964, and formed a government the next day. Both Labour and the Conservatives told Smith that a positive result at the ''indaba'' would not be recognised by Britain as representative of the people, and the Conservatives turned down Salisbury's invitation to send observers. Smith pressed on, telling parliament that he would ask the tribal chiefs and headmen "to consult their people in the traditional manner", then hold the ''indaba'' as planned. On 22 October 196 chiefs and 426 headmen from across the country gathered at Domboshawa

Domboshava is a peri-urban residential area in the province of Mashonaland East, Zimbabwe. It is located in an area of granite hills about north of Harare and is named after the enormous and beautiful granite hills. The name is derived from ...

, just north-east of Salisbury, and began their deliberations. Smith hoped that Britain, having taken part in such ''indabas'' in the past, might send a delegation at the last minute, but none arrived, much to his annoyance, particularly as the British government's Commonwealth Secretary Arthur Bottomley was only across the Zambezi

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

in Lusaka

Lusaka (; ) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was about 3.3 milli ...

at the time.

While the chiefs conferred, Northern Rhodesia became independent Zambia on 24 October 1964, emulating Nyasaland, which had achieved statehood as Malawi three months earlier. Reasoning that it was no longer necessary to refer to itself as "Southern" in the absence of a northern counterpart, Southern Rhodesia began calling itself simply Rhodesia. The same day, the commander of the Rhodesian Army

The Rhodesian Security Forces were the military forces of the Rhodesian government. The Rhodesian Security Forces consisted of a ground force (the Rhodesian Army), the Rhodesian Air Force, the British South Africa Police, and various personnel ...

, Major-General John "Jock" Anderson, resigned, announcing publicly that he was doing so because of his opposition to UDI, which he said he could not go along with because of his oath of allegiance to the Queen. Interpreting this as a sign that Smith intended to declare independence if a majority backed it in the referendum, Wilson wrote a stiff letter to Smith on 25 October, warning him of the consequences of UDI, and demanding "a categorical assurance forthwith that no attempt at a unilateral declaration of independence on your part will be made". Smith expressed confusion as to what he had done to provoke this, and ignored it.

When the ''indaba'' ended on 26 October, the chiefs and headmen returned a unanimous decision to support the government's stand for independence under the 1961 constitution, attesting in their report that "people who live far away do not understand the problems of our country". This verdict was rejected by the nationalist movement on the grounds that the chiefs received governmental salaries; the chiefs countered that the black MPs in parliamentary opposition also received such salaries, but still opposed the government. Malvern, who was becoming perturbed by the RF's actions, dismissed the ''indaba'' as a "swindle", asserting that the chiefs no longer had any real power; the British simply ignored the whole exercise. On 27 October, Wilson released a firm statement regarding Britain's intended response to UDI, warning that Rhodesia's economic and political ties with Britain, the Commonwealth and most of the world would be immediately severed amid a campaign of sanctions if Smith's government went ahead with UDI. This was intended to discourage white Rhodesians from voting for independence in the referendum, for which the RF campaign slogan was "Yes means Unity, not UDI". Wilson was pleased when Douglas-Home, his leading opponent in the House of Commons, praised the statement as "rough but right". On 5 November 1964, Rhodesia's mostly white electorate voted "yes" to independence under the 1961 constitution by a margin of 89%, prompting Smith to declare that the British condition of acceptability to the people as a whole had been met.

Stalemate develops between Smith and Wilson

Smith wrote to Wilson the day after the referendum, asking him to send Bottomley to Salisbury for talks. Wilson replied that Smith should instead come to London. The British and Rhodesians exchanged often confrontational letters for the next few months. Alluding to the British financial aid pledged to Salisbury as part of the Federal dissolution arrangements, Wilson's High Commissioner in Salisbury, J B Johnston, wrote to the Rhodesian Cabinet Secretary Gerald B Clarke on 23 December that "talk of a unilateral declaration of independence is bound to throw a shadow of uncertainty on the future financial relations between the two governments". Smith was furious, seeing this as blackmail, and on 13 January 1965 wrote to Wilson: "I am so incensed at the line of your High Commissioner's letter that I am replying directly to you ... It would appear that any undertakings given by the British government are worthless ... such immoral behaviour on the part of the British government makes it impossible for me to continue negotiations with you with any confidence that our standards of fair play, honesty and decency will prevail." The two premiers were brought together in person in late January 1965, when Smith travelled to London for Sir Winston Churchill's funeral. Following an episode concerning Smith's non-invitation to a luncheon at Buckingham Palace after the funeral—noticing the Rhodesian's absence, the Queen sent a royal

The two premiers were brought together in person in late January 1965, when Smith travelled to London for Sir Winston Churchill's funeral. Following an episode concerning Smith's non-invitation to a luncheon at Buckingham Palace after the funeral—noticing the Rhodesian's absence, the Queen sent a royal equerry

An equerry (; from French ' stable', and related to ' squire') is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attendant, usually up ...

to Smith's hotel to retrieve him, reportedly causing Wilson much irritation—the two Prime Ministers inconclusively debated at 10 Downing Street. They differed on most matters, but agreed on a visit to Rhodesia the next month by Bottomley and the Lord Chancellor, Lord Gardiner, to gauge public opinion and meet political and commercial figures. Bottomley and Gardiner visited Rhodesia from 22 February to 3 March, collected a wide cross-section of opinions, including some from black Rhodesians, and on returning to Britain reported to the House of Commons that they were "not without hope of finding a way towards a solution that will win the support of all communities and lead to independence and prosperity for all Rhodesians". Bottomley also condemned black-on-black political violence, and dismissed the idea of introducing majority rule through military force.

The RF called a new general election for May 1965 and, campaigning on an election promise

An election promise or campaign promise is a promise or guarantee made to the public by a candidate or political party that is trying to win an election.

Across the Western world, political parties are highly likely to fulfill their election p ...

of independence, won all 50 "A"-roll seats (the voters for which were mostly white). Josiah Gondo

Josiah Moses Gondo (died 27 October 1972) was a Rhodesian politician, and a member of parliament (MP) from 1962 to his death. In May 1965, as leader of the United People's Party, he became the first black politician to serve as the Rhodesian Hous ...

, leader of the United People's Party, became Rhodesia's first black Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

. Opening parliament on 9 June, Gibbs told the Legislative Assembly that the RF's strengthened majority amounted to "a mandate to lead the country to its full independence", and announced that the new government had informed him of its intent to open its own diplomatic mission in Lisbon, separate from the British embassy there. The British and Rhodesians argued about this unilateral act by Salisbury, described by the historian J R T Wood as the "veritable straw in the wind", alongside the independence issue until Portugal accepted the mission in late September, much to Britain's fury and Rhodesia's delight. Hoping to bring Smith to heel by stonewalling him, Wilson's ministers deliberately delayed and frustrated the Rhodesian government in negotiations. Rhodesia was again excluded from the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in 1965. The UK's refusal of aid, the Lisbon mission, the informal arms embargo and other issues combined with this to cause the Rhodesian government's sense of alienation from Britain and the Commonwealth to deepen. In his memoirs, Smith accused the British of "resorting to politics of convenience and appeasement". Wilson, meanwhile, became exasperated by what he saw as Rhodesian inflexibility, describing the gap between the two governments as "between different worlds and different centuries".

Final steps to UDI

Amid renewed rumours of an impending Rhodesian UDI, Smith travelled to meet Wilson in London at the start of October 1965, telling the press that he intended to resolve the independence issue once and for all. Both the British and the Rhodesians were surprised by the large numbers of Britons who came out to support Smith during his visit. Smith accepted an invitation from the BBC to appear on its ''Twenty-Four Hours

24 (twenty-four) is the natural number following 23 and preceding 25.

The SI prefix for 1024 is yotta (Y), and for 10−24 (i.e., the reciprocal of 1024) yocto (y). These numbers are the largest and smallest number to receive an SI prefix to da ...

'' evening news and current affairs programme, but Downing Street blocked this at the last minute. Following largely abortive talks with Wilson, the Rhodesian Prime Minister flew home on 12 October. Desperate to avert UDI, Wilson travelled to Salisbury two weeks later to continue negotiations.

During these discussions, Smith referred to the last resort of a UDI on many occasions, though he said he hoped to find another way out of the quandary. He offered to increase black legislative representation by expanding the electorate along the lines of "one taxpayer, one vote"—which would enfranchise about half a million, but still leave most of the nation voteless—in return for a grant of independence. Wilson said this was insufficient, and countered that future black representation might be better safeguarded by Britain's withdrawal from the colonial government of the power it had held since 1923 to determine the size and makeup of its parliament. The Rhodesians were horrified by this prospect, particularly as Wilson's suggestion of it seemed to them to have removed the failsafe alternative of keeping the ''status quo''. Before the British Prime Minister left Rhodesia on 30 October 1965, he proposed a Royal Commission to gauge public opinion in the colony regarding independence under the 1961 constitution, possibly chaired by the Rhodesian Chief Justice Sir Hugh Beadle

Sir Thomas Hugh William Beadle, (6 February 1905 – 14 December 1980) was a Rhodesian lawyer, politician and judge who served as Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia from March 1961 to November 1965, and as Chief Justice of Rhodesia fro ...

, which would report its findings to both the British and Rhodesian Cabinets. Wilson confirmed in the House of Commons two days later that he intended to introduce direct British control over the Rhodesian parliamentary structure to ensure that progress was made towards majority rule.

Stalemate drew closer as the Rhodesian Cabinet resolved that since Wilson had ruled out maintenance of the ''status quo'', its only remaining options were to trust in the Royal Commission or declare independence. When the terms for the commission's visit were presented to Smith, he found that contrary to what had been discussed during the British Prime Minister's visit, the Royal Commission would operate on the basis that the 1961 constitution was unacceptable to the British government, and that Britain would not commit itself to accepting the final report. Smith said these conditions amounted to a "vote of no confidence in he commissionbefore they commenced", and therefore rejected them. "The impression you left with us of a determined effort to resolve our constitutional problem has been utterly dissipated", he wrote to Wilson on 5 November. "It would seem that you have now finally closed the door which you publicly claimed to have opened."

Amid frantic efforts by Beadle and others on both sides to revive the Royal Commission, the Rhodesian government had Gibbs announce a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

the same day on the grounds that black Rhodesian insurgents were reportedly entering the country. Smith denied that this foreshadowed a declaration of independence, but the publishing of his letter to Wilson in the press provoked a worldwide storm of speculation that UDI was imminent. Smith wrote again to Wilson on 8 November, asking him to appoint the Royal Commission under the terms they had agreed in Salisbury and to commit the British government to accepting its ruling, but Wilson did not immediately reply. On 9 November, the Rhodesian Cabinet sent a letter to Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, assuring her that Rhodesia would remain loyal to her personally "whatever happens".

Draft, adoption and signing

The Rhodesian Minister for Justice and Law and Order, Desmond Lardner-Burke, presented the rest of the Cabinet with a draft for the declaration of independence on 5 November 1965. When Jack Howman, Minister of Tourism and Information, said that he was also preparing a draft, the Cabinet decided to wait to see his version too. The ministers agreed that if an independence proclamation were issued, they would all sign it. On 9 November, the Cabinet jointly devised an outline for the proclamation document and the accompanying statement to be made by Smith. The final version of the declaration of independence was prepared by a sub-committee of civil servants headed by Gerald Clarke, the Cabinet Secretary, with the

The Rhodesian Minister for Justice and Law and Order, Desmond Lardner-Burke, presented the rest of the Cabinet with a draft for the declaration of independence on 5 November 1965. When Jack Howman, Minister of Tourism and Information, said that he was also preparing a draft, the Cabinet decided to wait to see his version too. The ministers agreed that if an independence proclamation were issued, they would all sign it. On 9 November, the Cabinet jointly devised an outline for the proclamation document and the accompanying statement to be made by Smith. The final version of the declaration of independence was prepared by a sub-committee of civil servants headed by Gerald Clarke, the Cabinet Secretary, with the United States Declaration of Independence