Alfred Charles Sharpton Jr. (born October 3, 1954) is an American

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

activist,

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

minister, talk show host and politician. Sharpton is the founder of the

National Action Network

The National Action Network (NAN) is a not-for-profit, civil rights organization founded by the Reverend Al Sharpton in New York City, New York, in early 1991. In a 2016 profile, '' Vanity Fair'' called Sharpton "arguably the country's most infl ...

. In 2004, he was

a candidate for the

Democratic nomination for the

U.S. presidential election. He hosts his own radio talk show, ''

Keepin' It Real'', and he makes frequent appearances on cable news television. In 2011, he was named the host of

MSNBC

MSNBC (originally the Microsoft National Broadcasting Company) is an American news-based pay television cable channel. It is owned by NBCUniversala subsidiary of Comcast. Headquartered in New York City, it provides news coverage and political ...

's ''

PoliticsNation'', a nightly talk show.

In 2015, the program was shifted to Sunday mornings.

In October 2020, ''PoliticsNation'' was rescheduled to Saturdays and Sundays, airing at 5:00 p.m. Eastern Time both days.

Early life

Alfred Charles Sharpton Jr. was born in the

Brownsville neighborhood of

Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

,

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, to Ada (née Richards) and Alfred Charles Sharpton Sr. The family has some

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

roots. He preached his first

sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

at the age of four and toured with

gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

singer

Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson ( ; born Mahala Jackson; October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to t ...

.

In 1963, Sharpton's father left his wife to have a relationship with Sharpton's half-sister. Ada took a job as a maid, but her income was so low that the family qualified for

welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specificall ...

and had to move from

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

Hollis,

Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, to the

public housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, def ...

projects in the

Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Sharpton graduated from

Samuel J. Tilden High School

Samuel J. Tilden High School is a New York City public high school in the East Flatbush section of Brooklyn, New York City. It was named for Samuel J. Tilden, the former governor of New York State and presidential candidate who, although carryin ...

in Brooklyn, and attended

Brooklyn College

Brooklyn College is a public university in Brooklyn, Brooklyn, New York. It is part of the City University of New York system and enrolls about 15,000 undergraduate and 2,800 graduate students on a 35-acre campus.

Being New York City's first publ ...

, dropping out after two years in 1975. In 1972, he accepted the position of youth director for the presidential campaign of Congresswoman

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita Chisholm ( ; ; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. Chisholm represented New York's 12th congressional distr ...

. Between the years 1973 and 1980 Sharpton served as

James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, dancer, musician, record producer and bandleader. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th century music, he is often referred to by the honor ...

's tour manager.

Activism

In 1969, Sharpton was appointed by

Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senator ...

to serve as youth director of the New York City branch of

Operation Breadbasket

Operation Breadbasket was an organization dedicated to improving the economic conditions of black communities across the United States of America.

Operation Breadbasket was founded as a department of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ...

,

a group that focused on the promotion of new and better jobs for

African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s.

[Candidates – Al Sharpton](_blank)

CNN's "America Votes 2004", Retrieved April 7, 2007

In 1971, Sharpton founded the

National Youth Movement to raise resources for impoverished youth.

[Sharpton Biography](_blank)

, thehistorymakers.com, web site access April 7, 2007

Bernhard Goetz

Bernhard Goetz shot four African-American men on a

New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system owned by the government of New York City and leased to the New York City Transit Authority, an affiliate agency of the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Opened on October 2 ...

train in

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

on December 22, 1984, when they approached him and tried to rob him. At his trial Goetz was cleared of all charges except for carrying an unlicensed firearm. Sharpton led several marches protesting what he saw as the weak prosecution of the case.

Sharpton and other civil rights leaders said Goetz's actions were racist and requested a federal civil rights investigation. A federal investigation concluded the shooting was due to an attempted robbery and not race.

Howard Beach

On December 20, 1986, three African-American men were assaulted in the

Howard Beach

Howard Beach is a neighborhood in the southwestern portion of the New York City borough of Queens. It is bordered to the north by the Belt Parkway and Conduit Avenue in Ozone Park, to the south by Jamaica Bay in Broad Channel, to the east by 1 ...

neighborhood of

Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

by a mob of white men. The three men were chased by their attackers onto the

Belt Parkway

The Belt Parkway is the name given to a series of connected limited-access highways that form a belt-like circle around the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. The Belt Parkway comprises three of the four parkways in what is known as t ...

, where one of them,

Michael Griffith, was struck and killed by a passing motorist.

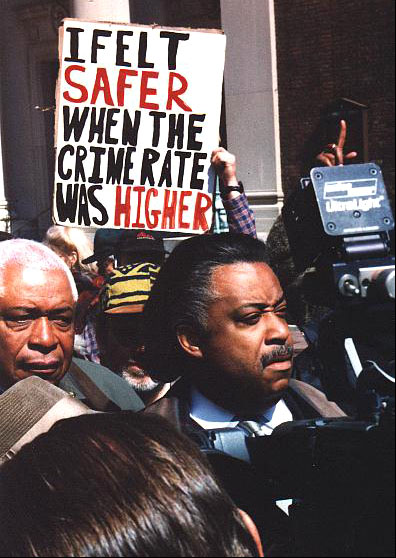

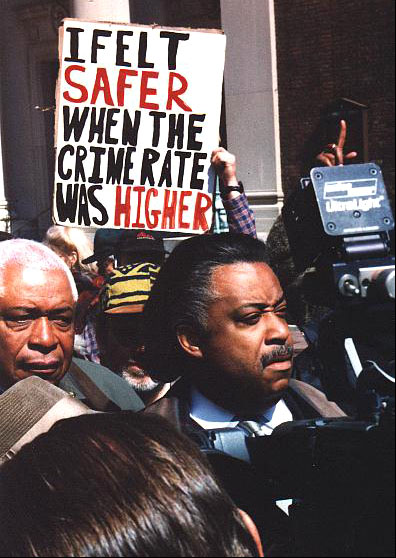

A week later, on December 27, Sharpton led 1,200 demonstrators on a march through the streets of Howard Beach. Residents of the neighborhood, who were overwhelmingly white, yelled racial epithets at the protesters, who were largely black. A

special prosecutor

In the United States, a special counsel (formerly called special prosecutor or independent counsel) is a lawyer appointed to investigate, and potentially prosecute, a particular case of suspected wrongdoing for which a conflict of interest exis ...

was appointed by New York Governor

Mario Cuomo

Mario Matthew Cuomo (, ; June 15, 1932 – January 1, 2015) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 52nd governor of New York for three terms, from 1983 to 1994. A member of the Democratic Party, Cuomo previously served as t ...

after the two surviving victims refused to co-operate with the Queens

district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a l ...

. Sharpton's role in the case helped propel him to national prominence.

Bensonhurst

On August 23, 1989, four African-American teenagers were beaten by a group of 10 to 30 white Italian-American youths in

Bensonhurst

Bensonhurst is a residential neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bordered on the northwest by 14th Avenue, on the northeast by 60th Street, on the southeast by Avenue P and 22nd ...

, a

Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

neighborhood. One Bensonhurst resident, armed with a handgun, shot and killed 16-year-old Yusef Hawkins.

In the weeks following the assault and murder, Sharpton led several marches through Bensonhurst. The first protest, just days after the incident, was greeted by neighborhood residents shouting "Niggers go home" and holding watermelons to mock the demonstrators.

Sharpton also threatened that Hawkins's three companions would not cooperate with prosecutor

Elizabeth Holtzman

Elizabeth Holtzman (born August 11, 1941) is an American attorney and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives from New York's 16th congressional district as a member of the Democratic Party from 1973 to 1981. She then ...

unless her office agreed to hire more black attorneys. In the end, they cooperated.

In May 1990, when one of the two leaders of the mob was acquitted of the most serious charges brought against him, Sharpton led another protest through Bensonhurst. In January 1991, when other members of the gang were given light sentences, Sharpton planned another march for January 12, 1991. Before that demonstration began, neighborhood resident Michael Riccardi tried to kill Sharpton by stabbing him in the chest. Sharpton recovered from his wounds, and later asked the judge for leniency when Riccardi was sentenced.

National Action Network

In 1991, Sharpton founded the

National Action Network

The National Action Network (NAN) is a not-for-profit, civil rights organization founded by the Reverend Al Sharpton in New York City, New York, in early 1991. In a 2016 profile, '' Vanity Fair'' called Sharpton "arguably the country's most infl ...

, an organization designed to increase voter education, to provide services to those in

poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse social, economic, and political causes and effects. When evaluating poverty in ...

, and to support small community businesses. In 2016,

Boise Kimber, an associate of Sharpton and a member of his NAN national board, along with businessman and philanthropist Don Vaccaro, launched Grace Church Websites, a non-profit organization that helps churches create and launch their own websites.

[

]

Crown Heights riot

The Crown Heights riot

The Crown Heights riot was a race riot that took place from August 19 to August 21, 1991, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York City. Black residents attacked orthodox Jewish residents, damaged their homes, and looted businesses. Th ...

began on August 19, 1991, after a car driven by a Jewish man, and part of a procession led by an unmarked police car, went through an intersection and was struck by another vehicle causing it to veer onto the sidewalk where it accidentally struck and killed a seven-year-old Guyanese boy named Gavin Cato and severely injured his cousin Angela. Witnesses could not agree upon the speed and could not agree whether the light was yellow or red. One of the factors that sparked the riot was the arrival of a private ambulance, which was later discovered to be on the orders of a police officer who was worried for the Jewish driver's safety, removed him from the scene while Cato lay pinned under his car.[ After being removed from under the car, Cato and his cousin were treated soon after by a city ambulance. Caribbean-American and African-American residents of the neighborhood rioted for four consecutive days fueled by rumors that the private ambulance had refused to treat Cato.][ During the riot black youths looted stores,][ beat Jews in the street,][ and clashed with groups of Jews, hurling rocks and bottles at one another after Yankel Rosenbaum, a visiting student from Australia, was stabbed and killed by a member of a mob while some chanted "Kill the Jew", and "get the Jews out".

Sharpton marched through Crown Heights and in front of the ]headquarters

Headquarters (commonly referred to as HQ) denotes the location where most, if not all, of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. In the United States, the corporate headquarters represents the entity at the center or the to ...

of the Chabad

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch (), is an Orthodox Jewish Hasidic dynasty. Chabad is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, particularly for its outreach activities. It is one of the largest Hasidic group ...

-Lubavitch Hasidic movement

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

, shortly after the riot, with about 400 protesters (who chanted "Whose streets? Our streets!" and "No justice, no peace

"No justice, no peace" is a political slogan which originated during protests against acts of ethnic violence against African Americans. Its precise meaning is contested. The slogan was used as early as 1986, following the killing of Michael Gri ...

!"), in spite of Mayor David Dinkins

David Norman Dinkins (July 10, 1927 – November 23, 2020) was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993. He was the first African American to hold the office.

Before enterin ...

' attempts to keep the march from happening.[ Some commentators felt Sharpton inflamed tensions by making remarks that included "If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their ]yarmulkes

A , , or , plural ), also called ''yarmulke'' (, ; yi, יאַרמלקע, link=no, , german: Jarmulke, pl, Jarmułka or ''koppel'' ( yi, קאפל ) is a brimless cap, usually made of cloth, traditionally worn by Jewish males to fulfill the c ...

back and come over to my house." In his eulogy for Cato, Sharpton said, "The world will tell us he was killed by accident. Yes, it was a social accident...It’s an accident to allow an apartheid ambulance service in the middle of Crown Heights...Talk about how Oppenheimer in South Africa sends diamonds straight to Tel Aviv and deals with the diamond merchants right here in Crown Heights. The issue is not anti-Semitism; the issue is apartheid...All we want to say is what Jesus said: If you offend one of these little ones, you got to pay for it. No compromise, no meetings, no kaffe klatsch, no skinnin’ and grinnin’. Pay for your deeds."

In the decades since, Sharpton has conceded that his language and tone "sometimes exacerbated tensions" though he insisted that his marches were peaceful. In a 2019 speech to a Reform Jewish

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

gathering, Sharpton said that he could have "done more to heal rather than harm". He recalled receiving a call from Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was married to Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she w ...

at the time, during which she told him "sometimes you are tempted to speak to the applause of the crowd rather than the heights of the cause, and you will say cheap things to get cheap applause rather than do high things to raise the nation higher".

Freddy's Fashion Mart

In 1995 a black Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement Church, the United House of Prayer, which owned a retail property on 125th Street, asked Fred Harari, a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

tenant who operated Freddie's Fashion Mart, to evict his longtime subtenant, a black-owned record store called The Record Shack. Sharpton led a protest in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

against the planned eviction of The Record Shack, in which he told the protesters, "We will not stand by and allow them to move this brother so that some white interloper can expand his business."

On December 8, 1995, Roland J. Smith Jr., one of the protesters, entered Harari's store with a gun and flammable liquid, shot several customers and set the store on fire. The gunman fatally shot himself, and seven store employees died of smoke inhalation. Fire Department officials discovered that the store's sprinkler had been shut down, in violation of the local fire code. Sharpton claimed that the perpetrator was an open critic of himself and his nonviolent tactics. In 2002, Sharpton expressed regret for making the racial remark "white interloper" but denied responsibility for inflaming or provoking the violence.

On December 8, 1995, Roland J. Smith Jr., one of the protesters, entered Harari's store with a gun and flammable liquid, shot several customers and set the store on fire. The gunman fatally shot himself, and seven store employees died of smoke inhalation. Fire Department officials discovered that the store's sprinkler had been shut down, in violation of the local fire code. Sharpton claimed that the perpetrator was an open critic of himself and his nonviolent tactics. In 2002, Sharpton expressed regret for making the racial remark "white interloper" but denied responsibility for inflaming or provoking the violence.[

]

Amadou Diallo

In 1999, Sharpton led a protest to raise awareness about the death of Amadou Diallo, an immigrant from

In 1999, Sharpton led a protest to raise awareness about the death of Amadou Diallo, an immigrant from Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

who was shot dead by NYPD

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

officers. Sharpton claimed that Diallo's death was the result of police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

and racial profiling

Racial profiling or ethnic profiling is the act of suspecting, targeting or discriminating against a person on the basis of their ethnicity, religion or nationality, rather than on individual suspicion or available evidence. Racial profiling involv ...

. Although all four defendants were found not guilty of any crimes in the criminal trial, Diallo's family was later awarded $3 million in a wrongful death suit filed against the city.

Tyisha Miller

In May 1999, Sharpton, Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senator ...

, and other activists protested the December 1998 fatal police shooting of Tyisha Miller

Tyisha Shenee Miller (March 9, 1979 – December 28, 1998) was an African American woman from Rubidoux, California. She was shot and killed by police officers called by family members who could not wake her as she lay unconscious in a car with a g ...

in central Riverside, California

Riverside is a city in and the county seat of Riverside County, California, United States, in the Inland Empire metropolitan area. It is named for its location beside the Santa Ana River. It is the most populous city in the Inland Empire an ...

. Miller, a 19-year-old African-American woman, had sat unconscious in a locked car with a flat tire and the engine left running, parked at a local gas station. After her relatives had called 9-1-1

, usually written 911, is an emergency telephone number for the United States, Canada, Mexico, Panama, Palau, Argentina, Philippines, Jordan, as well as the North American Numbering Plan (NANP), one of eight N11 codes. Like other emergency nu ...

, Riverside Police Department

The Riverside Police Department is the law enforcement agency responsible for the city of Riverside, California.

History

The Riverside Police Department was founded in 1896 and has grown from a small frontier town police force to a large metro ...

officers who responded to the scene observed a gun in the young woman's lap, and according to their accounts, she was shaking and foaming at the mouth, and in need of medical attention. When officers decided to break her window to reach her, as one officer reached for the weapon, she allegedly awoke and clutched her firearm, prompting several officers to open fire, hitting her 23 times and killing her. When the Riverside County

Riverside County is a county located in the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 2,418,185, making it the fourth-most populous county in California and the 10th-most populous in the Unit ...

district attorney stated that the officers involved had erred in judgement but committed no crime, declining to file criminal charges against them, Sharpton participated in protests which reached their zenith when protestors spilled onto the busy SR 91, completely stopping traffic. Sharpton was arrested for his participation and leadership in these protests.Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

".

Vieques

In 2001, Sharpton was jailed for 90 days on trespassing charges while protesting against U.S. military target practice exercises in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

near a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

bombing site. Sharpton, held in a Puerto Rican lockup for two days and then imprisoned at Metropolitan Detention Center, Brooklyn

The Metropolitan Detention Center, Brooklyn (MDC Brooklyn) is a United States federal administrative detention facility in the Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City. It holds male and female prisoners of all security levels. It ...

on May 25, 2001, He was released on August 17, 2001.

Ousmane Zongo

In 2002, Sharpton was involved in protests following the death of West African immigrant Ousmane Zongo

Ousmane Zongo ( – May 22, 2003) was a Burkinabé arts trader living in the United States who was shot and killed by Brian Conroy, a New York City Police Department officer during a warehouse raid on May 22, 2003. Zongo was not armed. Conroy ...

. Zongo, who was unarmed, was shot by an undercover police officer during a raid on a warehouse in the Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

neighborhood of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Sharpton met with the family and also provided some legal services.[As Outrage Mounts in New York Over the Police Killing of Another African Immigrant, Democracy Now! Interviews Kadiatou Diallo, Mother of Amadou Diallo.](_blank)

, Democracy Now!, Tuesday, May 27, 2003.

Sean Bell

On November 25, 2006, Sean Bell was shot and killed in the

On November 25, 2006, Sean Bell was shot and killed in the Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

section of Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, New York, by plainclothes detectives from the New York Police Department in a hail of 50 bullets. The incident sparked fierce criticism of the police from the public and drew comparisons to the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo. Three of the five detectives involved in the shooting went to trial in 2008 on charges ranging from manslaughter to reckless endangerment but were found not guilty.

On May 7, 2008, in response to the acquittals of the officers, Sharpton coordinated peaceful protests at major river crossings in New York City, including the Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a hybrid cable-stayed/ suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River ...

, the Queensboro Bridge

The Queensboro Bridge, officially named the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, is a cantilever bridge over the East River in New York City. Completed in 1909, it connects the neighborhood of Long Island City in the borough of Queens with the Upper East ...

, the Triborough Bridge

The Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (RFK Bridge; formerly known and still commonly referred to as the Triborough Bridge) is a complex of bridges and elevated expressway viaducts in New York City. The bridges link the boroughs of Manhattan, Queens, a ...

, the Manhattan Bridge

The Manhattan Bridge is a suspension bridge that crosses the East River in New York City, connecting Lower Manhattan at Canal Street with Downtown Brooklyn at the Flatbush Avenue Extension. The main span is long, with the suspension cables be ...

, the Holland Tunnel

The Holland Tunnel is a vehicular tunnel under the Hudson River that connects the New York City neighborhood of Hudson Square in Lower Manhattan to the east with Jersey City in New Jersey to the west. The tunnel is operated by the Port Author ...

, and the Queens–Midtown Tunnel

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel (also sometimes called the Midtown Tunnel) is a vehicular tunnel under the East River in New York City, connecting the boroughs of Manhattan and Queens. The tunnel consists of a pair of tubes, each carrying two ...

. Sharpton and about 200 others were arrested for blocking traffic and resisting police orders to disperse.

Dunbar Village

On March 11, 2008, Sharpton held a press conference to highlight what he said was unequal treatment of four suspected rapists in a high-profile crime in the Dunbar Village Housing Projects in West Palm Beach, Florida

West Palm Beach is a city in and the county seat of Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. It is located immediately to the west of the adjacent Palm Beach, which is situated on a barrier island across the Lake Worth Lagoon. The populati ...

. The suspects, who were young black men, were arrested for allegedly raping and beating a black Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

an woman at gunpoint. The crime also involved forcing the woman to perform oral sex on her 12-year-old son.[

]

Reclaim the Dream commemorative march

On August 28, 2010, Sharpton and other civil rights leaders led a march to commemorate the 47th anniversary of the historic

On August 28, 2010, Sharpton and other civil rights leaders led a march to commemorate the 47th anniversary of the historic March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic righ ...

. After gathering at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., thousands of people marched five miles to the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institut ...

.

Tanya McDowell

In June 2011, Sharpton spoke at a rally in support of Tanya McDowell, who was arrested and charged with larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Engla ...

for allegedly registering her son for kindergarten in the wrong public school district using a false address. She claimed to spend time in both a Bridgeport, Connecticut

Bridgeport is the List of municipalities in Connecticut, most populous city and a major port in the U.S. state of Connecticut. With a population of 148,654 in 2020, it is also the List of cities by population in New England, fifth-most populous ...

, apartment and a homeless shelter in Norwalk, where her son was registered.

George Zimmerman

Following the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin

On the night of February 26, 2012, in Sanford, Florida, United States, George Zimmerman fatally shot Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African-American boy. Zimmerman, a 28-year-old man of mixed race, was the neighborhood watch coordinator for his ...

by George Zimmerman

George Michael Zimmerman (born October 5, 1983) is an American man who fatally shot Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black boy, in Sanford, Florida, on February 26, 2012. On July 13, 2013, he was acquitted of second-degree murder in '' Flori ...

, Sharpton led several protests and rallies criticizing the Sanford Police Department over the handling of the shooting and called for Zimmerman's arrest: "Zimmerman should have been arrested that night. You cannot defend yourself against a pack of Skittles and iced tea." Sean Hannity

Sean Patrick Hannity (born December 30, 1961) is an American talk show host, conservative political commentator, and author. He is the host of ''The Sean Hannity Show'', a nationally syndicated talk radio show, and has also hosted a commentar ...

accused Sharpton and MSNBC of "rush ngto judgment" in the case. MSNBC issued a statement in which they said Sharpton "repeatedly called for calm" and further investigation. Following the acquittal of Zimmerman, Sharpton called the not guilty verdict an "atrocity" and "a slap in the face to those that believe in justice". Subsequently, Sharpton and his organization, National Action Network

The National Action Network (NAN) is a not-for-profit, civil rights organization founded by the Reverend Al Sharpton in New York City, New York, in early 1991. In a 2016 profile, '' Vanity Fair'' called Sharpton "arguably the country's most infl ...

, held rallies in several cities denouncing the verdict and called for "Justice for Trayvon".

Eric Garner

After the July 2014

After the July 2014 death of Eric Garner

On July 17, 2014, Eric Garner was killed in the New York City borough of Staten Island after Daniel Pantaleo, a New York City Police Department (NYPD) officer, put him in a prohibited chokehold while arresting him. Video footage of the incide ...

on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

, New York, by a New York City Police Department

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

officer, Daniel Pantaleo, Sharpton organized a peaceful protest in Staten Island on the afternoon of July 19, and condemned the police's use of the chokehold on Garner, saying that "there is no justification" for it. Sharpton had also planned to lead a protest on August 23, in which participants would have driven over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge

The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge ( ) is a suspension bridge connecting the New York City boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn. It spans the Narrows, a body of water linking the relatively enclosed New York Harbor with Lower New York Bay and th ...

, then traveled to the site of the altercation and the office of District Attorney Dan Donovan This idea was scrapped in favor of Sharpton leading a peaceful march along Bay Street in Staten Island, where Garner died; over 5,000 people marched in the demonstration.

Barack Obama

In 2014, Glenn Thrush of ''Politico

''Politico'' (stylized in all caps), known originally as ''The Politico'', is an American, German-owned political journalism newspaper company based in Arlington County, Virginia, that covers politics and policy in the United States and intern ...

'' described Sharpton as an "adviser" to President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

and as Obama's "go-to man" on racial issues.

Ministers March for Justice

On August 28, 2017, the fifty-fourth anniversary of the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic righ ...

at which Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

gave his "I Have a Dream

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called ...

" speech, Sharpton organized the Ministers March for Justice, promising to bring a thousand members of the clergy to Washington, D.C., to deliver a "unified moral rebuke" to President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

. Several thousand religious leaders were present, including Christians, Jews, Muslims, and Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism, Sikhism (Sikhi), a Monotheism, monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Gu ...

s. ''Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' columnist Dana Milbank

Dana Timothy Milbank (born April 27, 1968) is an American author and columnist for ''The Washington Post''.

Personal life

Milbank was born to a Jewish family, the son of Ann C. and Mark A. Milbank. He is a graduate of Yale University, where he wa ...

wrote that "President Trump has united us, after all. He brought together the Rev. Al Sharpton and the Jews."

George Floyd

At the funeral of George Floyd

George Perry Floyd Jr. (October 14, 1973 – May 25, 2020) was an African-American man who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during an arrest made after a store clerk suspected Floyd may have used a counterfeit twe ...

on June 4, 2020, Sharpton delivered a eulogy where he called for the four Minneapolis policemen involved in Floyd's murder to be brought to justice. He also criticized President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

for his talk about "bringing in the military" when "some kids wrongly start violence that this family doesn’t condone" and that Trump has "not said one word about 8 minutes and 46 seconds of police murder of George Floyd". On April 20, 2021, with the conviction of Derek Chauvin for murdering George Floyd, Sharpton led prayer with the Floyd family in Minneapolis.

Political views

In September 2007, Sharpton was asked whether he considered it important for the US to have a black president. He responded, "It would be a great moment as long as the black candidate was supporting the interest that would inevitably help our people. A lot of my friends went with

In September 2007, Sharpton was asked whether he considered it important for the US to have a black president. He responded, "It would be a great moment as long as the black candidate was supporting the interest that would inevitably help our people. A lot of my friends went with Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 199 ...

and regret it to this day. I don't assume that just because somebody's my color, they're my kind. But I'm warming up to Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

, but I'm not there yet."

Sharpton has spoken out against cruelty to animals

Cruelty to animals, also called animal abuse, animal neglect or animal cruelty, is the infliction by omission (neglect) or by commission by humans of suffering or harm upon non-human animals. More narrowly, it can be the causing of harm or suf ...

in a video recorded for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA; , stylized as PeTA) is an American animal rights nonprofit organization based in Norfolk, Virginia, and led by Ingrid Newkirk, its international president. PETA reports that PETA entities have ...

.[Rev. Al Sharpton Preaches Compassion for Chickens](_blank)

, Kentuckyfriedcruelty.com, Retrieved April 7, 2007

Sharpton is a supporter of equal rights for gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

s and lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

s and same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same Legal sex and gender, sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being ...

. During his 2004 presidential campaign, Sharpton said he thought it was insulting to be asked to discuss the issue of gay marriage. "It's like asking do I support black marriage or white marriage.... The inference of the question is that gays are not like other human beings." Sharpton is leading a grassroots movement to eliminate homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitude (psychology), attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, h ...

within the Black church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their ...

.[Sharpton Chides Black Churches Over Homophobia, Gay Marriage](_blank)

, Dyana Bagby, Houston Voice, January 24, 2006

In 2014, Sharpton began a push for criminal justice reform

Criminal justice reform addresses structural issues in Criminal justice, criminal justice systems such as racial profiling, police brutality, overcriminalization, mass incarceration, and recidivism. Criminal justice reform can take place at any poi ...

, citing the fact that black people represent a greater proportion of those arrested and incarcerated in America.

In August 2017, Sharpton called for the federal government to stop maintaining the Jefferson Memorial

The Jefferson Memorial is a presidential memorial built in Washington, D.C. between 1939 and 1943 in honor of Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, a central intellectual force behind the Am ...

in Washington, D.C., because Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

owned 600 slaves and had a sexually abusive relationship with his slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

. He said taxpayer funds should not be used to care for monuments to slave-owners and that private museums were preferable. He went on to elaborate: "People need to understand that people were enslaved. Our families were victims of this. Public monuments o people like Jefferson

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), pl ...

are supported by public funds. You're asking me to subsidize the insult to my family."

Sharpton is an opponent of the Defund the Police

"Defund the police" is a slogan that supports removing funds from police departments and reallocating them to non-policing forms of public safety and community support, such as social services, youth services, housing, education, healthcare and o ...

movement, charging that the idea is being pushed by " latte liberals" who were out of touch with the African-American community, and that black and poor neighbourhoods "need proper policing" to protect the inhabitants from higher crime rates.

Reputation

Sharpton's supporters praise "his ability and willingness to defy the power structure that is seen as the cause of their suffering"Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

Ed Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was may ...

, one-time foe, said that Sharpton deserves the respect he enjoys among black Americans: "He is willing to go to jail for them, and he is there when they need him."Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

said that Sharpton is "the voice of the voiceless and a champion for the downtrodden". A 2013 Zogby Analytics poll found that one quarter of African Americans said that Sharpton speaks for them.

His critics describe him as "a political radical who is to blame, in part, for the deterioration of race relations".Orlando Patterson

Horace Orlando Patterson (born 5 June 1940) is a Jamaican historical and cultural sociologist known for his work regarding issues of race and slavery in the United States and Jamaica, as well as the sociology of development. He is the John Cowl ...

has referred to him as a racial arsonist,liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

columnist Derrick Z. Jackson has called him the black equivalent of Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

and Pat Buchanan

Patrick Joseph Buchanan (; born November 2, 1938) is an American paleoconservative political commentator, columnist, politician, and broadcaster. Buchanan was an assistant and special consultant to U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, an ...

. Sharpton sees much of the criticism as a sign of his effectiveness. "In many ways, what they consider criticism is complimenting my job," he said. "An activist's job is to make public civil rights issues until there can be a climate for change."[

]

Controversies

Tobacco industry funding

In 2021, Sharpton was criticized for leading a tobacco industry pushback against a proposed ban on the sale of menthol cigarettes using "cynically manipulative" arguments while his National Action Network accepted funding from tobacco companies.

Comments on Mormons

During 2007, Sharpton was accused of bigotry for comments he made on May 7, 2007, concerning presidential candidate Mitt Romney

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American politician, businessman, and lawyer serving as the junior United States senator from Utah since January 2019, succeeding Orrin Hatch. He served as the 70th governor of Massachusetts f ...

and his religion, Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects of t ...

:

In response, a representative for Romney told reporters that "bigotry toward anyone because of their beliefs is unacceptable." The Catholic League compared Sharpton to Don Imus

John Donald Imus Jr. (July 23, 1940 – December 27, 2019), also known mononymously as Imus, was an American radio personality, television show host, recording artist, and author. His radio show, ''Imus in the Morning'', was aired on various stat ...

, and said that his remarks "should finish his career".

On May 9, during an interview on ''Paula Zahn NOW

Paula Ann Zahn (; born February 24, 1956) is an American journalist and newscaster who has been an anchor at ABC News, CBS News, Fox News, and CNN. She currently produces and hosts the true crime documentary series ''On the Case with Paula Zahn'' ...

'', Sharpton said that his views on Mormonism were based on the " Mormon Church's traditionally racist views regarding blacks" and its interpretation of the so-called "Curse of Ham

The curse of Ham is described in the Book of Genesis as imposed by the patriarch Noah upon Ham's son Canaan. It occurs in the context of Noah's drunkenness and is provoked by a shameful act perpetrated by Noah's son Ham, who "saw the nakedness o ...

." On May 10, Sharpton called two apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and apologized to them for his remarks and asked to meet with them. A spokesman for the Church confirmed that Sharpton had called and said that "we appreciate it very much, Rev. Sharpton's call, and we consider the matter closed."[Sharpton apologizes, plans Utah trip](_blank)

, ''Deseret News

The ''Deseret News'' () is the oldest continuously operating publication in the American west. Its multi-platform products feature journalism and commentary across the fields of politics, culture, family life, faith, sports, and entertainment. Th ...

'', May 11, 2007. He also apologized to "any member of the Mormon church" who was offended by his comments.Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Utah, where he met with Elder M. Russell Ballard

Melvin Russell Ballard Jr. (born October 8, 1928) is an American businessman and religious leader who is currently the Acting President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He has ...

, a leader of the Church, and Elder Robert C. Oaks of the Church's Presidency of the Seventy

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by a ...

.

Racial and homophobic comments

On February 13, 1994, Sharpton told a student audience at Kean University

Kean University () is a public university in Union Township, Union County, New Jersey, Union and Hillside, New Jersey. It is part of New Jersey's public system of higher education.

Kean University was founded in 1855 in Newark, New Jersey, as th ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

: "White folks was in the caves while we was building empires," he said. "We built pyramids before Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

even knew what architecture was. We taught philosophy and astrology icand mathematics before Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

and them Greek homos ever got around to it." Sharpton defended his comments by saying that the term "homo" was not homophobic; however, he added that he no longer uses the term. At the same lecture, he said, "Do some cracker come and tell you, 'Well my mother and father blood go back to the Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

,' you better hold your pocket. That ain't nothing to be proud of, that means their forefathers was crooks."Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

as "cocktail sip Negroes" or "yellow niggers".

Tawana Brawley rape case

On November 28, 1987, Tawana Brawley, a 15-year-old black girl, was found smeared with feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

, lying in a garbage bag, her clothing torn and burned and with various slurs and epithets written on her body in charcoal.rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

d by six white men, some of them police officers, in the town of Wappinger, New York

Wappinger, officially the Town of Wappinger, is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States. The town is located in the Hudson River Valley region, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan, on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. The ...

.Alton H. Maddox

Alton Henry Maddox Jr. (July 21, 1945 – April 23, 2023) was an American lawyer who was involved in several high-profile civil rights cases in the 1980s.

Education

Maddox was born on July 21, 1945, in Inkster, Michigan, and grew up in Newnan, ...

and C. Vernon Mason joined Sharpton in support of Brawley. A grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

was convened; after seven months of examining police and medical records, the jury found "overwhelming evidence" that Brawley had fabricated her story.Dutchess County

Dutchess County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 295,911. The county seat is the city of Poughkeepsie. The county was created in 1683, one of New York's first twelve counties, and later organ ...

prosecutor, Steven Pagones, of racism and of being one of the perpetrators of the alleged abduction and rape. The three were successfully sued for defamation, and were ordered to pay $345,000 in damages, with the jury finding Sharpton liable for making seven defamatory statements about Pagones, Maddox for two, and Mason for one. Sharpton refused to pay his share of the damages; it was later paid by a number of black business leaders including Johnnie Cochran

Johnnie Lee Cochran Jr.Adam Bernstei ''The Washington Post'', March 30, 2005; retrieved April 17, 2006. (; October 2, 1937 – March 29, 2005) was an American lawyer best known for his leadership role in the defense and criminal acquittal ...

.[ Interview with Al Sharpton, David Shankbone, '']Wikinews

Wikinews is a free-content news wiki and a project of the Wikimedia Foundation that works through collaborative journalism. Wikipedia cofounder Jimmy Wales has distinguished Wikinews from Wikipedia by saying, "On Wikinews, each story is to be ...

'', December 3, 2007.

Work as FBI informant

Sharpton said in 1988 that he informed for the government in order to stem the flow of crack cocaine into black neighborhoods. He denied informing on civil rights leaders.

In 2002, HBO's ''Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel

''Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel'' is a monthly sports news magazine on HBO. Since its debut on April 2, 1995, the program has been presented by television journalist and sportscaster Bryant Gumbel.

Overview

Format

Each episode consists of fou ...

'' aired a 19-year-old FBI videotape of an undercover sting operation showing Sharpton with an undercover FBI agent posing as a Latin American drug lord. During the discussion, the undercover agent offered Sharpton a 10% commission for arranging drug sales. On the videotape, Sharpton mostly nods and allows the FBI agent to do most of the talking. No drug deal was ever consummated, and no charges were brought against Sharpton as a result of the tape.

In April 2014, The Smoking Gun

The Smoking Gun is a website that posts legal documents, arrest records, and police mugshots on a daily basis. The intent is to bring to the public light information that is somewhat obscure or unreported by more mainstream media sources. Most o ...

obtained documents indicating that Sharpton became an FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

informant in 1983 following Sharpton's role in a drug sting involving Colombo crime family

The Colombo crime family (, ) is an Italian American Mafia crime family and is the youngest of the "Five Families" that dominate organized crime activities in New York City within the criminal organization known as the American Mafia. It was du ...

captain Michael Franzese

Michael Franzese () ('' né'' Grillo; born May 27, 1951) is an American former mobster who was a caporegime in the Colombo crime family, and son of former underboss Sonny Franzese. Franzese was enrolled in a pre-med program at Hofstra University ...

. Sharpton allegedly recorded incriminating conversations with Genovese

Genovese is an Italian surname meaning, properly, someone from Genoa. Its Italian plural form '' Genovesi'' has also developed into a surname.

People

* Alfred Genovese (1931–2011), American oboist

* Alfredo Genovese (born 1964), Argentine ar ...

and Gambino family mobsters, contributing to the indictments of several underworld figures. Sharpton is referred to in FBI documents as "CI-7".

Summarizing the evidence supporting that Sharpton was an active FBI informant in the 1980s, William Bastone

William Bastone (born July 24, 1961) is editor and co-founder of The Smoking Gun website. In 1997, Bastone and his wife Barbara Glauber, who is a graphic designer, created The Smoking Gun with freelance journalist Daniel Green. In 1984, Bastone w ...

, the Smoking Gun's founder, stated: "If he (Sharpton) didn't think he was an informant, the 'Genovese squad' of the FBI and NYPD officials sure knew him to be an informant. He was paid to be an informant, he carried a briefcase with a recording device in it, and he made surreptitious tape recordings of a Gambino crime family member 10 separate times as an informant. He did it at the direction of the FBI, he was prepped by the FBI, was handed the briefcase by the FBI and was debriefed after the meetings. That's an informant." Sharpton disputes portions of the allegations.

Sharpton is alleged to have secretly recorded conversations with black activists in the 1980s regarding Joanne Chesimard (Assata Shakur

Assata Olugbala Shakur (born JoAnne Deborah Byron; July 16, 1947; also married name, JoAnne Chesimard) is an American political activist who was a member of the Black Liberation Army (BLA). In 1977, she was convicted in the first-degree murder ...

) and other underground black militants. Veteran activist Ahmed Obafemi told the ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in ta ...

'' that he had long suspected Sharpton of taping him with the bugged briefcase.

LoanMax

In 2005, Sharpton appeared in three television commercials for LoanMax, an automobile title loan

A title loan (also known as a car title loan) is a type of secured loan where borrowers can use their vehicle title as collateral. Borrowers who get title loans must allow a lender to place a lien on their car title, and temporarily surrender the ...

company. He was criticized for his appearance because LoanMax reportedly charges fees which are the equivalent of 300% APR loans.

Tax issues

In 1993, Sharpton pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for failing to file a state income tax return. Later, the authorities discovered that one of Mr. Sharpton's for-profit companies, Raw Talent, which he used as a repository for money from speaking engagements, was also not paying taxes, a failure that continued for years.Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

reported that Sharpton and his businesses owed almost $1.5 million in unpaid taxes and penalties. Sharpton owed $931,000 in federal income tax and $366,000 to New York, and his for-profit company, Rev. Al Communications, owed another $176,000 to the state.New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' reported that the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory ta ...

had sent subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

s to several corporations that had donated to Sharpton's National Action Network

The National Action Network (NAN) is a not-for-profit, civil rights organization founded by the Reverend Al Sharpton in New York City, New York, in early 1991. In a 2016 profile, '' Vanity Fair'' called Sharpton "arguably the country's most infl ...

. In 2007 New York State Attorney General Andrew Cuomo began investigating the National Action Network, because it failed to make proper financial reports, as required for non-profits. According to the ''Post'', several major corporations, including Anheuser-Busch

Anheuser-Busch Companies, LLC is an American brewing company headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. Since 2008, it has been wholly owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV (AB InBev), now the world's largest brewing company, which owns multiple glo ...

and Colgate-Palmolive

Colgate-Palmolive Company is an American multinational consumer products company headquartered on Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The company specializes in the production, distribution, and provision of household, health car ...

, have donated thousands of dollars to the National Action Network. The ''Post'' asserted that the donations were made to prevent boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

s or rallies by the National Action Network.

Sharpton countered the investigative actions with a charge that they reflected a political agenda by United States agencies.

On September 29, 2010, Robert Snell of ''The Detroit News

''The Detroit News'' is one of the two major newspapers in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. The paper began in 1873, when it rented space in the rival ''Detroit Free Press'' building. ''The News'' absorbed the '' Detroit Tribune'' on Februa ...

'' reported that the Internal Revenue Service had filed a notice of federal tax lien

A tax lien is a lien which is imposed upon a property by law in order to secure the payment of taxes. A tax lien may be imposed for the purpose of collecting delinquent taxes which are owed on real property or personal property, or it may be im ...

against Sharpton in New York City in the amount of over $538,000.[Robert Snell, "Sharpton faced with fresh tax woe," '']The Detroit News

''The Detroit News'' is one of the two major newspapers in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. The paper began in 1873, when it rented space in the rival ''Detroit Free Press'' building. ''The News'' absorbed the '' Detroit Tribune'' on Februa ...

'', September 29, 2010, at . Sharpton's lawyer asserts that the notice of federal tax lien relates to Sharpton's year 2009 federal income tax return, the due date of which has been extended to October 15, 2010, according to the lawyer. However, the Snell report states that the lien relates to taxes ''assessed during 2009''.[

According to '']The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Sharpton and his for-profit businesses owed $4.5 million in state and federal taxes as of November 2014.

Personal life

In 1971 while touring with James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, dancer, musician, record producer and bandleader. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th century music, he is often referred to by the honor ...

, he met future wife Kathy Jordan, who was a backup singer. Sharpton and Jordan married in 1980. The couple separated in 2004. In July 2013, the ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in ta ...

'' reported that Sharpton, while still married to his second wife (Kathy Jordan), now had a self-described "girlfriend", Aisha McShaw, aged 35, and that the couple had "been an item for months.... photographed at elegant bashes all over the country". McShaw, the ''Daily News'' reported, referred to herself professionally as both a "personal stylist" and "personal banker".

Sharpton is an honorary member of Phi Beta Sigma

Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. () is a historically African American fraternity. It was founded at Howard University in Washington, D.C. on January 9, 1914, by three young African-American male students with nine other Howard students as char ...

fraternity.

Religion

Sharpton was licensed and ordained a Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement minister by Bishop F. D. Washington at the age of nineBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

. He was re-baptized as a member of the Bethany Baptist Church in 1994 by the Reverend William Augustus Jonesatheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

writer Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

, defending his religious faith and his belief in the existence of God.

Assassination attempt

On January 12, 1991, Sharpton escaped serious injury when he was stabbed in the chest in the schoolyard at P.S. 205 by Michael Riccardi while Sharpton was preparing to lead a protest through

On January 12, 1991, Sharpton escaped serious injury when he was stabbed in the chest in the schoolyard at P.S. 205 by Michael Riccardi while Sharpton was preparing to lead a protest through Bensonhurst

Bensonhurst is a residential neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bordered on the northwest by 14th Avenue, on the northeast by 60th Street, on the southeast by Avenue P and 22nd ...

in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York. The intoxicated attacker was apprehended by Sharpton's aides and handed over to police, who were present for the planned protest.

In 1992, Riccardi was convicted of first-degree assault. Sharpton asked the judge for leniency when sentencing Riccardi.[Lueck, Thomas]

"City Settles Sharpton Suit Over Stabbing"

''The New York Times'', December 9, 2003.

Indirect biological relation to Strom Thurmond

In February 2007, genealogist Megan Smolenyak

Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak,Sam Roberts''The New York Times'', September 14, 2006. born October 9, is an American genealogist, author, and speaker. She is also a consultant for the FBI and NCIS.

Education

Smolenyak holds a BSFS in Foreign Service ...

discovered that Sharpton's great-grandfather, Coleman Sharpton, was a slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

owned by Julia Thurmond, whose grandfather was Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

's great-great-grandfather. Coleman Sharpton was later freed.

The Sharpton family name originated with Coleman Sharpton's previous owner, who was named Alexander Sharpton.

Political campaigns

Sharpton has run unsuccessfully for elected office on multiple occasions. Of his unsuccessful runs, he said that winning office may not have been his goal, saying in an interview: "Much of the media criticism of me assumes their goals and they impose them on me. Well, those might not be my goals. So they will say, 'Well, Sharpton has not won a political office.' But that might not be my goal! Maybe I ran for political office to change the debate, or to raise the social justice question."[ Sharpton ran for a ]United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

seat from New York in 1988

File:1988 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The oil platform Piper Alpha explodes and collapses in the North Sea, killing 165 workers; The USS Vincennes (CG-49) mistakenly shoots down Iran Air Flight 655; Australia celebrates its Australian ...

, 1992

File:1992 Events Collage V1.png, From left, clockwise: 1992 Los Angeles riots, Riots break out across Los Angeles, California after the Police brutality, police beating of Rodney King; El Al Flight 1862 crashes into a residential apartment buildi ...

, and 1994

File:1994 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 1994 Winter Olympics are held in Lillehammer, Norway; The Kaiser Permanente building after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; A model of the MS Estonia, which Sinking of the MS Estonia, sank in ...

. In 1997

File:1997 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The movie set of ''Titanic'', the highest-grossing movie in history at the time; ''Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone'', is published; Comet Hale-Bopp passes by Earth and becomes one of t ...

, he ran for Mayor of New York City. During his 1992 bid, he and his wife lived in a home in Englewood, New Jersey