Retour des cendres on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''retour des cendres'' (literally "return of the ashes", though "ashes" is used here as meaning his mortal remains, as he was not cremated) was the return of the mortal remains of

The ''retour des cendres'' (literally "return of the ashes", though "ashes" is used here as meaning his mortal remains, as he was not cremated) was the return of the mortal remains of

At 7pm on 7 July 1840 the frigate '' Belle Poule'' left

At 7pm on 7 July 1840 the frigate '' Belle Poule'' left

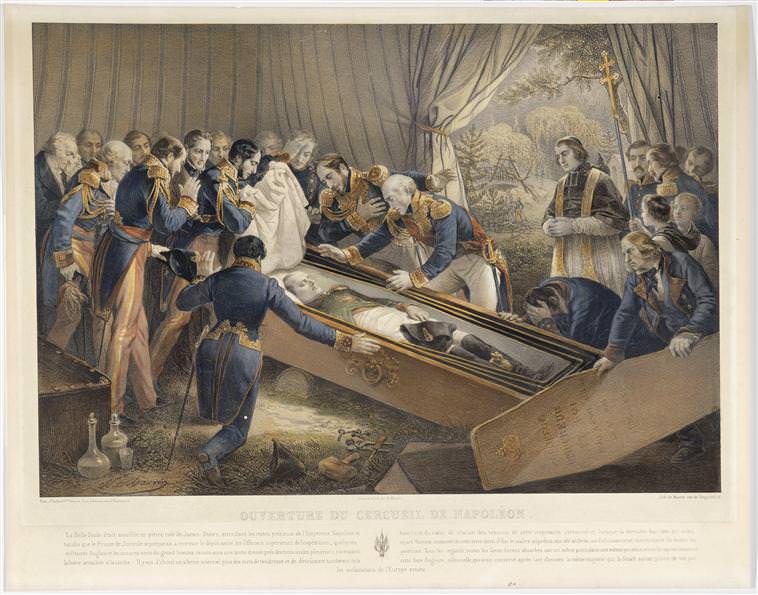

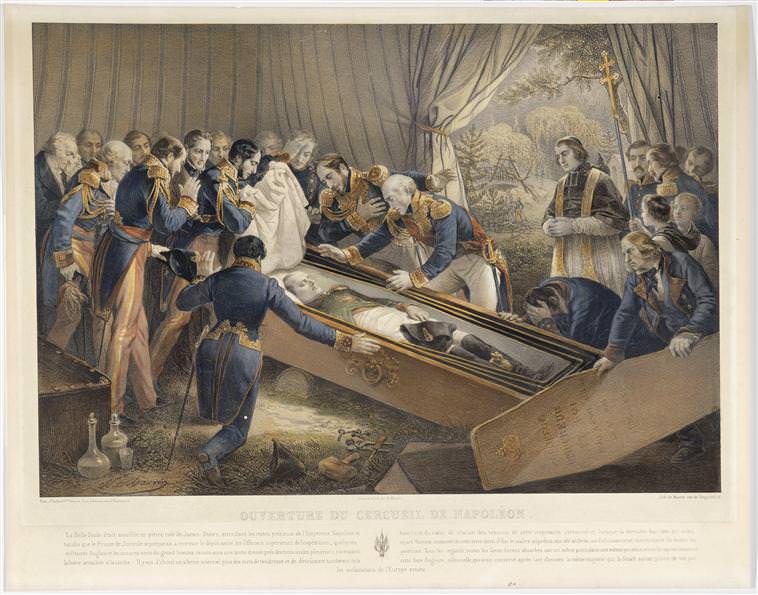

The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct. The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner and Doret, doctor Guillard (chief surgeon of the ''Belle-Poule'') and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux. The British section was made up of William Wilde, Colonel Hodson and Mr Scale (members of the island's colonial council), Mr Thomas, Mr Brooke, Colonel Trelawney (the island's artillery commander), naval Lieutenant Littlehales, Captain Alexander (representing Governor Middlemore, who was indisposed, although he eventually arrived accompanied by his son and an aide) and Mr Darling (interior decorator at Longwood during Napoleon's captivity).

By the light of torches, the British soldiers set to work. They removed the grille, then the stones that formed a border to the tomb. The topsoil had already been removed and the French shared among themselves the flowers that had been growing in it. The soldiers then pulled up the three slabs that were closing the pit over. Long efforts were needed to break through the masonry enclosing the coffin. At 9.30 the last slab was raised and the coffin could be seen. Coquereau took some water from the nearby spring, blessed it and sprinkled it over the coffin, before reciting the psalm '' De profundis''. The coffin was raised and transported into a large blue and white striped tent that had been put up the previous day. Then they proceeded to open the bier, in complete silence. The first coffin, of

The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct. The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner and Doret, doctor Guillard (chief surgeon of the ''Belle-Poule'') and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux. The British section was made up of William Wilde, Colonel Hodson and Mr Scale (members of the island's colonial council), Mr Thomas, Mr Brooke, Colonel Trelawney (the island's artillery commander), naval Lieutenant Littlehales, Captain Alexander (representing Governor Middlemore, who was indisposed, although he eventually arrived accompanied by his son and an aide) and Mr Darling (interior decorator at Longwood during Napoleon's captivity).

By the light of torches, the British soldiers set to work. They removed the grille, then the stones that formed a border to the tomb. The topsoil had already been removed and the French shared among themselves the flowers that had been growing in it. The soldiers then pulled up the three slabs that were closing the pit over. Long efforts were needed to break through the masonry enclosing the coffin. At 9.30 the last slab was raised and the coffin could be seen. Coquereau took some water from the nearby spring, blessed it and sprinkled it over the coffin, before reciting the psalm '' De profundis''. The coffin was raised and transported into a large blue and white striped tent that had been put up the previous day. Then they proceeded to open the bier, in complete silence. The first coffin, of  When the lid was lifted what appeared was described by a witness as "a white form – of uncertain shape", which was the only thing visible at first at the light of the torches, briefly sparking fears that the body had decomposed extensively; however, it was discovered that the white satin padding from the coffin lid had detached and fallen over Napoleon's body, covering it like a shroud. Doctor Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body laid comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand laid over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognizable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors. As the body became dehydrated, its hairs started to protrude more and more from the skin, making it look as if the hairs had grown; this being a common phenomenon in well-preserved bodies. In Napoleon's case, this phenomenon was most prominently displayed in what would have been his beard and his chin was stippled with the beginnings of a bluish beard. The hands for their part were very white and the fingers were thin and long; the fingernails were still intact and attached to the fingers and they seemed to have grown longer, also protruding because of the dryness of the skin.

Napoleon wore his famous green uniform of the colonel of chasseurs which was perfectly preserved; his chest was still crossed by the red ribbon of the

When the lid was lifted what appeared was described by a witness as "a white form – of uncertain shape", which was the only thing visible at first at the light of the torches, briefly sparking fears that the body had decomposed extensively; however, it was discovered that the white satin padding from the coffin lid had detached and fallen over Napoleon's body, covering it like a shroud. Doctor Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body laid comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand laid over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognizable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors. As the body became dehydrated, its hairs started to protrude more and more from the skin, making it look as if the hairs had grown; this being a common phenomenon in well-preserved bodies. In Napoleon's case, this phenomenon was most prominently displayed in what would have been his beard and his chin was stippled with the beginnings of a bluish beard. The hands for their part were very white and the fingers were thin and long; the fingernails were still intact and attached to the fingers and they seemed to have grown longer, also protruding because of the dryness of the skin.

Napoleon wore his famous green uniform of the colonel of chasseurs which was perfectly preserved; his chest was still crossed by the red ribbon of the  All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back. After two minutes' examination, Dr. Guillard proposed that he continue examining the body and open the jars containing the heart and the stomach, in part so that they could confirm or disprove the findings of the autopsy performed by the English when Napoleon died and which had found a perforated ulcer in his stomach. Gourgaud, however, suppressing his tears, became angry and ordered that the coffin be closed at once. The doctor complied and replaced the satin padding, spraying it with a little creosote as a preservative before putting back on the original tin lid (though without re-soldering it) and the original mahogany lid. The original lead coffin was then re-soldered.

The original lead coffin and its contents were then placed into a new ebony coffin with combination lock that had been brought from France. This ebony coffin, made in Paris, was 2.56m long, 1.05m wide and 0.7m deep. Its design imitated classical Roman coffins. The lid bore the sole inscription "Napoléon" in gold letters. Each of the four sides was decorated with the letter N in gilded bronze and there were six strong bronze rings for handles. On the coffin were also inscribed the words "Napoléon Empereur mort à Sainte-Hélène le 05 Mai 1821 (Napoleon, Emperor, died at St Helena on 05 May 1821)".

After the combination lock had been closed, the ebony coffin was placed in a new oak coffin, designed to protect that of ebony. Then this mass, totalling 1,200 kilos, was hoisted by 43 gunners onto a solid hearse, draped in black with four plumes of black feathers at each corner and drawn with great difficulty by four horses caparisoned in black. The coffin was covered with a large (4.3m by 2.8m) black pall made of single piece of velvet sown with golden bees and bearing eagles surmounted by imperial crowns at its corners as well as a large silver cross. The ladies of Saint Helena offered to the French commissioner the tricolour flags that would be used in the ceremony and which they had made with their own hands, and the imperial flag that would be flown by ''Belle Poule''.

All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back. After two minutes' examination, Dr. Guillard proposed that he continue examining the body and open the jars containing the heart and the stomach, in part so that they could confirm or disprove the findings of the autopsy performed by the English when Napoleon died and which had found a perforated ulcer in his stomach. Gourgaud, however, suppressing his tears, became angry and ordered that the coffin be closed at once. The doctor complied and replaced the satin padding, spraying it with a little creosote as a preservative before putting back on the original tin lid (though without re-soldering it) and the original mahogany lid. The original lead coffin was then re-soldered.

The original lead coffin and its contents were then placed into a new ebony coffin with combination lock that had been brought from France. This ebony coffin, made in Paris, was 2.56m long, 1.05m wide and 0.7m deep. Its design imitated classical Roman coffins. The lid bore the sole inscription "Napoléon" in gold letters. Each of the four sides was decorated with the letter N in gilded bronze and there were six strong bronze rings for handles. On the coffin were also inscribed the words "Napoléon Empereur mort à Sainte-Hélène le 05 Mai 1821 (Napoleon, Emperor, died at St Helena on 05 May 1821)".

After the combination lock had been closed, the ebony coffin was placed in a new oak coffin, designed to protect that of ebony. Then this mass, totalling 1,200 kilos, was hoisted by 43 gunners onto a solid hearse, draped in black with four plumes of black feathers at each corner and drawn with great difficulty by four horses caparisoned in black. The coffin was covered with a large (4.3m by 2.8m) black pall made of single piece of velvet sown with golden bees and bearing eagles surmounted by imperial crowns at its corners as well as a large silver cross. The ladies of Saint Helena offered to the French commissioner the tricolour flags that would be used in the ceremony and which they had made with their own hands, and the imperial flag that would be flown by ''Belle Poule''.

At 8am on Sunday 18 October ''Belle Poule'', ''Favorite'' and ''Oreste'' set sail. ''Oreste'' rejoined the Levant division, whilst the two other ships sailed towards France at full speed, fearful of being attacked. No notable setback occurred to ''Belle Poule'' and ''Favorite'' during the first 13 days of this voyage, though on 31 October they met the merchantman ''Hambourg'', whose captain gave Joinville news of Europe, confirming the news he had received from Doret. The threat of war was confirmed by the Dutch ship ''Egmont'', en route for

At 8am on Sunday 18 October ''Belle Poule'', ''Favorite'' and ''Oreste'' set sail. ''Oreste'' rejoined the Levant division, whilst the two other ships sailed towards France at full speed, fearful of being attacked. No notable setback occurred to ''Belle Poule'' and ''Favorite'' during the first 13 days of this voyage, though on 31 October they met the merchantman ''Hambourg'', whose captain gave Joinville news of Europe, confirming the news he had received from Doret. The threat of war was confirmed by the Dutch ship ''Egmont'', en route for

In the meantime, in October 1840, a new ministry nominally presided over by Marshal

In the meantime, in October 1840, a new ministry nominally presided over by Marshal

The date for the reburial was set for 15 December. Victor Hugo evoked this day in his ''Les Rayons et les Ombres'':

:"O frozen sky! and sunlight pure! shining bright in history!

:''Funereal triumph, imperial torch!''

:Let the people's memory hold you forever,

:::Day beautiful as glory,

:::Cold as the tomb

Even as far as London, poems commemorating the event were published; one read in part:

:Ah! Luckless to the nations! Luckless day!

:When from Helena's rock they bore away,

:And gave again to France the mouldering bones

:Of him, beneath whose monarchy the thrones

:Of Earth's huge empires shook-that might one,

:The archon of the world-NAPOLEON!

Despite the temperature never rising above 10 degrees Celsius, the crowd of spectators stretching from the

The date for the reburial was set for 15 December. Victor Hugo evoked this day in his ''Les Rayons et les Ombres'':

:"O frozen sky! and sunlight pure! shining bright in history!

:''Funereal triumph, imperial torch!''

:Let the people's memory hold you forever,

:::Day beautiful as glory,

:::Cold as the tomb

Even as far as London, poems commemorating the event were published; one read in part:

:Ah! Luckless to the nations! Luckless day!

:When from Helena's rock they bore away,

:And gave again to France the mouldering bones

:Of him, beneath whose monarchy the thrones

:Of Earth's huge empires shook-that might one,

:The archon of the world-NAPOLEON!

Despite the temperature never rising above 10 degrees Celsius, the crowd of spectators stretching from the  The cortège arrived at the Invalides around 1:30, and at 2 pm it reached the gate of honour. The king and all France's leading statesmen were waiting in the royal chapel, the Église du Dôme. Joinville was to make a short speech, but nobody had remembered to forewarn him – he contented himself with a sabre salute and the king mumbled a few unintelligible words. '' Le Moniteur'' described the scene as best it could:

The cortège arrived at the Invalides around 1:30, and at 2 pm it reached the gate of honour. The king and all France's leading statesmen were waiting in the royal chapel, the Église du Dôme. Joinville was to make a short speech, but nobody had remembered to forewarn him – he contented himself with a sabre salute and the king mumbled a few unintelligible words. '' Le Moniteur'' described the scene as best it could:

General Atthalin stepped forward, bearing on a cushion the sword that Napoleon had worn at

General Atthalin stepped forward, bearing on a cushion the sword that Napoleon had worn at  The bearing of the old Marshal Moncey, the governor of the Invalides, somewhat redeemed the impertinence of the court and the politicians. For a fortnight he had been in agony, pressing his doctor to keep him alive at least to complete his role in the ceremony. At the end of the religious ceremony he managed to walk to the catafalque, sprinkled holy water on it and pronounced as the closing words: "And now, let us go home to die".

From 16 to 24 December, the Église des Invalides, illuminated as on the day of the ceremony, remained open to the public. The people had long disbelieved in Napoleon's death and a rumour spread that the tomb was only a cenotaph. It was claimed that on St Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy; and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned. Hugo wrote that, though the actual body was there, the people's good sense was not amiss:

The bearing of the old Marshal Moncey, the governor of the Invalides, somewhat redeemed the impertinence of the court and the politicians. For a fortnight he had been in agony, pressing his doctor to keep him alive at least to complete his role in the ceremony. At the end of the religious ceremony he managed to walk to the catafalque, sprinkled holy water on it and pronounced as the closing words: "And now, let us go home to die".

From 16 to 24 December, the Église des Invalides, illuminated as on the day of the ceremony, remained open to the public. The people had long disbelieved in Napoleon's death and a rumour spread that the tomb was only a cenotaph. It was claimed that on St Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy; and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned. Hugo wrote that, though the actual body was there, the people's good sense was not amiss:

The Second Funeral of Napoleon

by Michael Angelo Titmarsh * A succinct chronology by Albert Benhamou {{italic title July Monarchy Napoleon History of Saint Helena Funerals in France 1840 in France December 1840 events Aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars Louis Philippe I

The ''retour des cendres'' (literally "return of the ashes", though "ashes" is used here as meaning his mortal remains, as he was not cremated) was the return of the mortal remains of

The ''retour des cendres'' (literally "return of the ashes", though "ashes" is used here as meaning his mortal remains, as he was not cremated) was the return of the mortal remains of Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

from the island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the burial in Hôtel des Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides ( en, "house of invalids"), commonly called Les Invalides (), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, as ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

in 1840, on the initiative of Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

and King Louis-Philippe.

Background

After defeat in theWar of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, and a number of German States defeated F ...

in 1814, Napoleon abdicated as emperor of the French, and was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. The following year he returned to France, took up the throne, and began the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

. The powers which had prevailed against him the previous year mobilised against him, and defeated the French in the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

. Napoleon returned to Paris and abdicated

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

on 22 June 1815. Foiled in his attempt to sail to the United States, he gave himself up to the British, who exiled him to the remote island of St Helena in the south Atlantic Ocean. He died and was buried there in 1821.

Previous attempts

In a codicil to his will, written in exile atLongwood House

Longwood House is a mansion in St. Helena and the final residence of Napoleon Bonaparte, the former Emperor of the French, during his exile on the island of Saint Helena, from 10 December 1815 until his death on 5 May 1821.

History

Longwood " ...

on St Helena on 16 April 1821, Napoleon had expressed a wish to be buried "on the banks of the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributarie ...

, in the midst of the French people hom Iloved so much". On the Emperor's death, Comte Bertrand unsuccessfully petitioned the British government to let Napoleon's wish be granted. He then petitioned the ministers of the newly restored Louis XVIII of France

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in e ...

, from whom he did not receive an absolute refusal, instead the explanation that the arrival of the remains in France would undoubtedly be the cause or pretext for political unrest that the government would be wise to prevent or avoid, but that his request would be granted as soon as the situation had calmed and it was safe enough to do so.

Course

Political discussions

Initiation

After theJuly Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

a petition demanding the remains' reburial in the base of the Colonne Vendôme

Colonne () is a commune in the Jura department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Jura department

The following is a list of the 494 communes of the Jura department of France.

The comm ...

(on the model of Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

's ashes, buried in the base of his column in Rome) was refused by the Chambre des Députés on 2 October 1830. However, ten years later, Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

, the new Président du Conseil under Louis-Philippe and a historian of the French Consulate

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

and First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

, dreamed of the return of the remains as a grand political ''coup de théâtre'' which would definitively achieve the rehabilitation of the Revolutionary and Imperial periods on which he was engaged in his ''Histoire de la Révolution française'' and ''Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire''. He also hoped to flatter the left's dreams of glory and restore the reputation of the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

(whose diplomatic relations with the rest of Europe were then under threat from its problems in Egypt, arising from its support for Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

).

It was, nonetheless, Louis-Philippe's policy to try to regain "all the glories of France", to which he had dedicated the Château de Versailles, turning it into a museum of French history. Yet he was still reluctant and had to be convinced to support the project against his own doubts. Among the rest of the royal family, the Prince de Joinville did not want to be employed on a job suitable for a "carter" or an "undertaker"; Queen Marie-Amélie adjudged that such an operation would be "fodder for hot-heads"; and their daughter Louise

Louise or Luise may refer to:

* Louise (given name)

Arts Songs

* "Louise" (Bonnie Tyler song), 2005

* "Louise" (The Human League song), 1984

* "Louise" (Jett Rebel song), 2013

* "Louise" (Maurice Chevalier song), 1929

*"Louise", by Clan of ...

saw it as "pure theatre". In early 1840, the government led by Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

appointed a twelve-member committee () to decide on the location and outline of the funerary monument and select its architect. The committee was chaired by politician Charles de Rémusat and included writers and artists such as Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier ( , ; 30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

While an ardent defender of Romanticism, Gautier's work is difficult to classify and rem ...

, David d'Angers and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

On 10 May 1840 François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the a ...

, then French ambassador in London, against his own will submitted an official request to the British government, which was immediately approved according to the promise made in 1822. For his part, the British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston privately found the idea nonsensical and wrote about it to his brother, presenting it in the following terms: "Here's a really French idea".

12 May

On 12 May, during discussion of a bill on sugars, theFrench Interior Minister

Minister of the Interior (french: Ministre de l'Intérieur; ) is a prominent position in the Government of France. The position is equivalent to the interior minister in other countries, like the Home Secretary in the United Kingdom, the Minis ...

Charles de Rémusat mounted the rostrum at the Chambre des Députés and said:

The minister then introduced a bill to authorise "funding of 1 million rancsfor translation of the Emperor Napoleon's mortal remains to the Église des Invalides and for construction of his tomb". This announcement caused a sensation. A heated discussion began in the press, raising all sorts of objections as to the theory and to the practicalities. The town of Saint-Denis petitioned on 17 May that he instead be buried at their basilica, the traditional burial place of French kings.

25–26 May

On 25 and 26 May the bill was discussed in the Chambre. It was proposed by Bertrand Clauzel, an old soldier of theFirst French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

who had been recalled by the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

and promoted to Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1 ...

. In the name of the he endorsed the choice of Les Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides ( en, "house of invalids"), commonly called Les Invalides (), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, as ...

as the burial site, not without discussing the other suggested solutions (besides Saint-Denis, the Arc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile (, , ; ) is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Place de l'Étoile—the ''étoile'' ...

, the Colonne Vendôme

Colonne () is a commune in the Jura department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Jura department

The following is a list of the 494 communes of the Jura department of France.

The comm ...

, the Panthéon de Paris

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was bu ...

and even the Madeleine had been suggested to him). He proposed that the funding be raised to 2 million, that the ship bringing the remains back be escorted by a whole naval squadron and that Napoleon would be the last person to be buried in the Invalides. Speeches were made by the republican critic of the Empire Glais-Bizoin, who stated that "Bonapartist ideas are one of the open wounds of our time; they represent that which is most disastrous for the emancipation of peoples, the most contrary to the independence of the human spirit." The proposal was defended by Odilon Barrot

Camille Hyacinthe Odilon Barrot (; 19 July 1791 – 6 August 1873) was a French politician who was briefly head of the council of ministers under President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1848–49.

Early life

Barrot was born at Villefort, Lozè ...

(the future president of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

's council in 1848), whilst the hottest opponent of it was Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869), was a French author, poet, and statesman who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic and the continuation of the Tricolore as the flag of France. ...

, who found the measure dangerous. Lamartine stated before the debate that "Napoleon's ashes are not yet extinguished, and we're breathing in their sparks". Before the sitting, Thiers tried to dissuade Lamartine from intervening but received the reply "No, Napoleon's imitators must be discouraged." Thiers replied "Oh! But who could think to imitate him today?", only to receive Lamartine's reply that then spread right round Paris – "I do beg your pardon, I meant to say Napoleon's parodists." During the debate Lamartine stated:

In conclusion Lamartine invited France to show that "she id not wishto create out of this ash war, tyranny, legitimate monarchs, pretenders, or even imitators". Hearing this peroration, which was implicitly directed against him, Thiers looked devastated on his bench. Even so, the Chambre was largely favourable and voted through the measures requested, although by 280 votes to 65 it did refuse to raise the funding from 1 to 2 million. The Napoleonic myth was already fully developed and only needed to be crowned. The July Monarchy's official poet Casimir Delavigne wrote:

:France, you have seen him again! Your cry of joy, O France,

:::Drowns out the noise of your cannon;

:Your people, a whole people reaching out from your riverbanks,

:::Holds out its arms to Napoleon.

4–6 June

On 4 or 6 June General Bertrand was received by Louis-Philippe, who gave him the Emperor's arms, which were placed in the treasury. Bertrand stated on this occasion: Louis-Philippe replied, with studied formality: This ceremony angeredJoseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the latter writing in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'':

After the arms ceremony Bertrand went to the Hôtel de ville and offered to the president of the Conseil Municipal the council chair that Napoleon had left to the capital – this is now in the Musée Carnavalet

The Musée Carnavalet in Paris is dedicated to the history of the city. The museum occupies two neighboring mansions: the Hôtel Carnavalet and the former Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau. On the advice of Baron Haussmann, the civil servant wh ...

.

Arrival at St Helena

At 7pm on 7 July 1840 the frigate '' Belle Poule'' left

At 7pm on 7 July 1840 the frigate '' Belle Poule'' left Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, escorted by the corvette ''Favorite''. The Prince of Joinville

The first known lord of Joinville (French ''sire'' or ''seigneur de Joinville'') in the county of Champagne appears in the middle of the eleventh century. The former lordship was raised into the Principality of Joinville under the House of Guise ...

, the king's third son and a career naval officer, was in command of the frigate and the expedition as a whole. Also on board the frigate were Philippe de Rohan-Chabot

Philippe-Ferdinand-Auguste de Rohan-Chabot (1815–1875), comte de Jarnac, was a French diplomat of aristocratic descent.

Descended from the ancient Breton family currently represented by Josselin de Rohan, the 14th Duke. He was the only son of ...

, an attaché to the French ambassador to the United Kingdom and commissioned by Thiers (wishing to gain reflected glory from any possible part of the expedition) to superintend the exhumation operations; generals Bertrand

Bertrand may refer to:

Places

* Bertrand, Missouri, US

* Bertrand, Nebraska, US

* Bertrand, New Brunswick, Canada

* Bertrand Township, Michigan, US

* Bertrand, Michigan

* Bertrand, Virginia, US

* Bertrand Creek, state of Washington

* Saint-Bert ...

and Gourgaud; Count Emmanuel de Las Cases (député for Finistère

Finistère (, ; br, Penn-ar-Bed ) is a department of France in the extreme west of Brittany. In 2019, it had a population of 915,090.

and son of Emmanuel de Las Cases

Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, comte de Las Cases (21 June 176615 May 1842) was a French atlas-maker and author, famed for an admiring book about Napoleon, ''Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène'' ("The Memorial of Saint Helena").

Life and caree ...

, the author of '' Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène''); and five people who had been domestic servants to Napoleon on Saint Helena (Saint-Denis – better known by the name Ali Le Mameluck – Noverraz, Pierron, Archambault and Coursot). Captain Guyet was in command of the corvette, which transported Louis Marchand

Louis Marchand (2 February 1669 – 17 February 1732) was a French Baroque organist, harpsichordist, and composer. Born into an organist's family, Marchand was a child prodigy and quickly established himself as one of the best known French vi ...

, Napoleon's chief valet de chambre, who had been with him on Saint Helena. Others on the expedition included Abbé Félix Coquereau (fleet almoner); Charner (Joinville's lieutenant and second in command), Hernoux (Joinville's aide-de-camp), Lieutenant Touchard (Joinville's orderly), General Bertrand's young son Arthur, and ship's doctor Rémy Guillard. Once the bill had been passed, the frigate was adapted to receive Napoleon's coffin: a candlelit chapel was built in the steerage, draped in black velvet embroidered with the Napoleonic symbol of silver bees, with a catafalque

A catafalque is a raised bier, box, or similar platform, often movable, that is used to support the casket, coffin, or body of a dead person during a Christian funeral or memorial service. Following a Roman Catholic Requiem Mass, a catafalque ...

at the centre guarded by four gilded wooden eagles.

The voyage lasted 93 days and, due to the youth of some of its crews, turned into a tourist trip, with the Prince dropping anchor at Cadiz for four days, Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

for two days and Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

for four days, while 15 days of balls and festivities were held at Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. The two ships finally reached Saint Helena on 8 October and in the roadstead found the French brig ''Oreste'', commanded by Doret, who had been one of the ensigns who had come up with a daring plan at île d'Aix to get Napoleon away on a lugger after Waterloo and who would later become a capitaine de corvette

Corvette captain is a rank in many navies which theoretically corresponds to command of a corvette (small warship). The equivalent rank in the United Kingdom, Commonwealth, and United States is lieutenant commander. The Royal Canadian Navy use ...

. Doret had arrived at Saint Helena to pay his last respects to Napoleon but he also brought worrying news – the Egyptian incident, combined with Thiers' aggressive policy, were very close to causing a diplomatic rupture between France and the United Kingdom. Joinville knew that the ceremony would be respected but began to fear he would be intercepted by British ships on the return trip.

The mission disembarked the following day and went to Plantation House, where the island's governor, Major-General George Middlemore

Lieutenant-General George Middlemore (died 18 November 1850, Tunbridge Wells) was a British Army officer and the first Governor of Saint Helena.

Originally commissioned in the 86th Regiment of Foot, he rose to command the 48th Regiment of Fo ...

was waiting for them. After a long interview with Joinville (with the rest of the mission waiting impatiently in the lounge), Middlemore appeared before the rest of the mission and announced "Gentlemen, the Emperor's mortal remains will be handed over to you on Thursday 15 October". The mission then set off for Longwood, via the Valley of the Tomb

The Valley of the Tomb (french: Vallée du Tombeau) is the site of Napoleon's tomb, on the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena in the south Atlantic Ocean, where he was buried following his death in exile on 5 May 1821. The valley had bee ...

(or Geranium Valley). Napoleon's tomb was in a solitary spot, covered by three slabs placed level with the soil. This very simple monument was surrounded by an iron grille, solidly fixed on a base and shaded by a weeping willow

''Salix babylonica'' (Babylon willow or weeping willow; ) is a species of willow native to dry areas of northern China, but cultivated for millennia elsewhere in Asia, being traded along the Silk Road to southwest Asia and Europe.Flora of China'' ...

, with another such tree lying dead by its side. All this was surrounded by a wooden fence and very close by was a spring whose fresh and clear water Napoleon had enjoyed. At the gate to the enclosure, Joinville dismounted, bared his head and approached the iron grille, followed by the rest of the mission. In a deep silence they contemplated the severe and bare tomb. After half an hour Joinville remounted and the expedition continued on its way. Lady Torbet, owner of the land where the tomb was sited, had set up a booth to sell refreshments for the few pilgrims to the tomb and was unhappy about the exhumation since it would eliminate her already small profits from it. They then went in pilgrimage to Longwood, which was in a very ruinous state – the furniture had disappeared, many walls were covered with graffiti, Napoleon's bedroom had become a stable where a farmer pastured his beasts and got a little extra income by guiding visitors around it. The sailors from ''Oreste'' grabbed the billiard table, which had been spared by the goats and sheep, and carried off the tapestry and anything else they could carry, all the while being loudly shouted at by the farmer with demands for compensation.

Exhumation

The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct. The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner and Doret, doctor Guillard (chief surgeon of the ''Belle-Poule'') and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux. The British section was made up of William Wilde, Colonel Hodson and Mr Scale (members of the island's colonial council), Mr Thomas, Mr Brooke, Colonel Trelawney (the island's artillery commander), naval Lieutenant Littlehales, Captain Alexander (representing Governor Middlemore, who was indisposed, although he eventually arrived accompanied by his son and an aide) and Mr Darling (interior decorator at Longwood during Napoleon's captivity).

By the light of torches, the British soldiers set to work. They removed the grille, then the stones that formed a border to the tomb. The topsoil had already been removed and the French shared among themselves the flowers that had been growing in it. The soldiers then pulled up the three slabs that were closing the pit over. Long efforts were needed to break through the masonry enclosing the coffin. At 9.30 the last slab was raised and the coffin could be seen. Coquereau took some water from the nearby spring, blessed it and sprinkled it over the coffin, before reciting the psalm '' De profundis''. The coffin was raised and transported into a large blue and white striped tent that had been put up the previous day. Then they proceeded to open the bier, in complete silence. The first coffin, of

The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct. The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner and Doret, doctor Guillard (chief surgeon of the ''Belle-Poule'') and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux. The British section was made up of William Wilde, Colonel Hodson and Mr Scale (members of the island's colonial council), Mr Thomas, Mr Brooke, Colonel Trelawney (the island's artillery commander), naval Lieutenant Littlehales, Captain Alexander (representing Governor Middlemore, who was indisposed, although he eventually arrived accompanied by his son and an aide) and Mr Darling (interior decorator at Longwood during Napoleon's captivity).

By the light of torches, the British soldiers set to work. They removed the grille, then the stones that formed a border to the tomb. The topsoil had already been removed and the French shared among themselves the flowers that had been growing in it. The soldiers then pulled up the three slabs that were closing the pit over. Long efforts were needed to break through the masonry enclosing the coffin. At 9.30 the last slab was raised and the coffin could be seen. Coquereau took some water from the nearby spring, blessed it and sprinkled it over the coffin, before reciting the psalm '' De profundis''. The coffin was raised and transported into a large blue and white striped tent that had been put up the previous day. Then they proceeded to open the bier, in complete silence. The first coffin, of mahogany

Mahogany is a straight-grained, reddish-brown timber of three tropical hardwood species of the genus ''Swietenia'', indigenous to the AmericasBridgewater, Samuel (2012). ''A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest''. Austin: Unive ...

, had to be sawn off at both ends to get out the second coffin, made of lead, which was then placed within the neo-classical, ebony coffin that had been brought for it from France. General Middlemore and Lieutenant Touchard then arrived and presented themselves, before the party proceeded to unsolder the lead coffin. The coffin inside this, again of mahogany, was remarkably well-preserved. Its screws were removed with difficulty. It was then possible to open, with infinite care, the final coffin, made of tin.

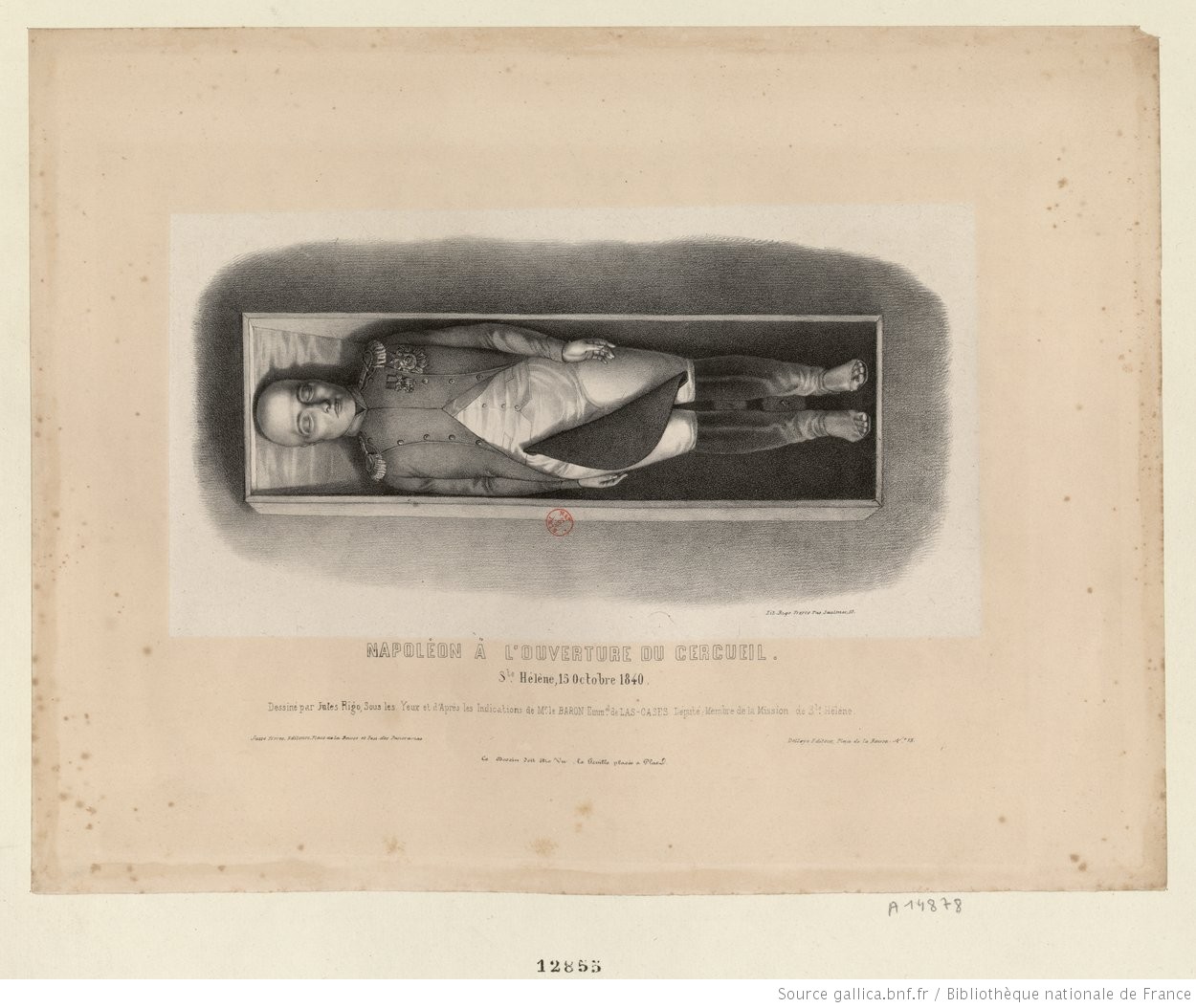

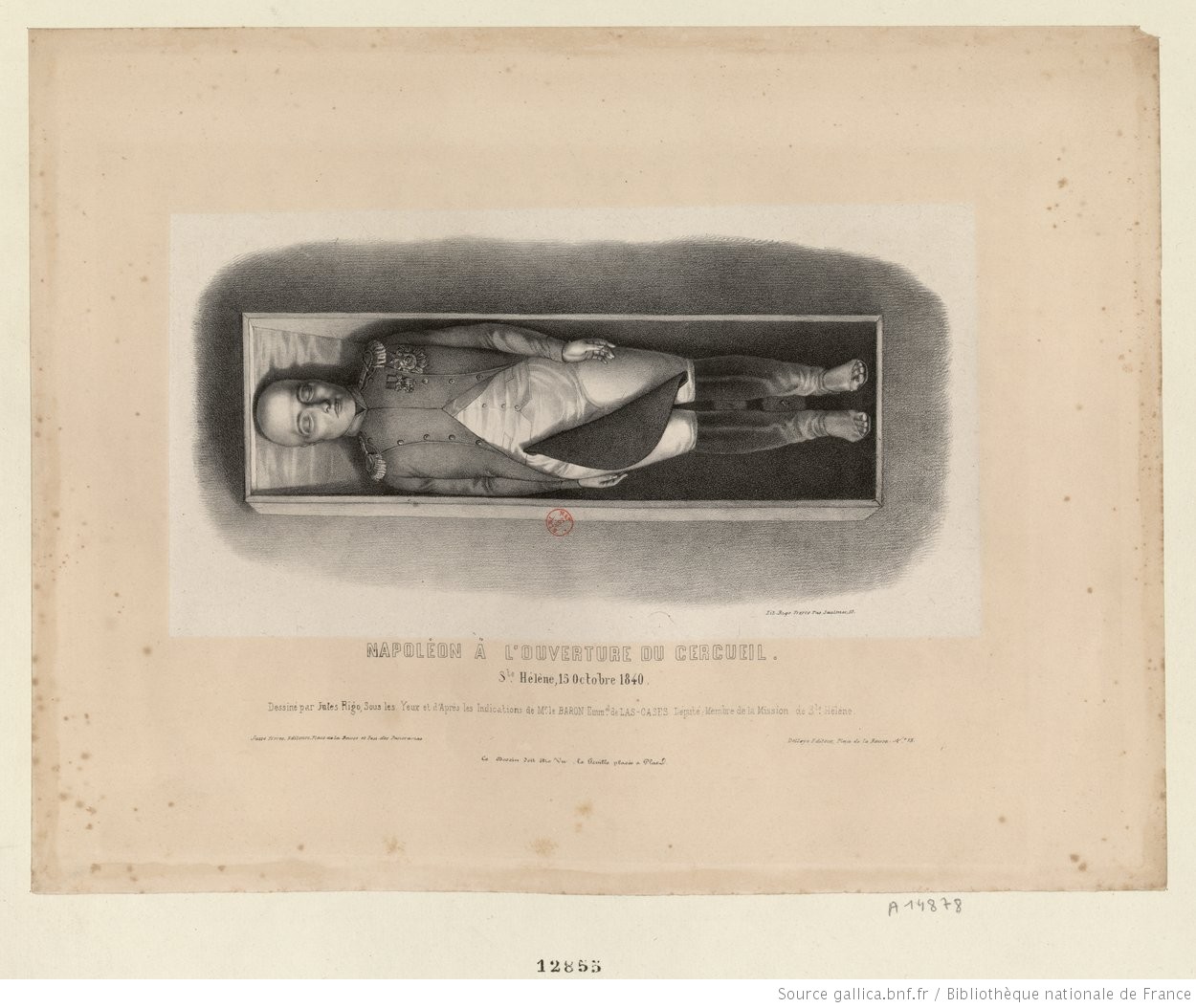

When the lid was lifted what appeared was described by a witness as "a white form – of uncertain shape", which was the only thing visible at first at the light of the torches, briefly sparking fears that the body had decomposed extensively; however, it was discovered that the white satin padding from the coffin lid had detached and fallen over Napoleon's body, covering it like a shroud. Doctor Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body laid comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand laid over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognizable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors. As the body became dehydrated, its hairs started to protrude more and more from the skin, making it look as if the hairs had grown; this being a common phenomenon in well-preserved bodies. In Napoleon's case, this phenomenon was most prominently displayed in what would have been his beard and his chin was stippled with the beginnings of a bluish beard. The hands for their part were very white and the fingers were thin and long; the fingernails were still intact and attached to the fingers and they seemed to have grown longer, also protruding because of the dryness of the skin.

Napoleon wore his famous green uniform of the colonel of chasseurs which was perfectly preserved; his chest was still crossed by the red ribbon of the

When the lid was lifted what appeared was described by a witness as "a white form – of uncertain shape", which was the only thing visible at first at the light of the torches, briefly sparking fears that the body had decomposed extensively; however, it was discovered that the white satin padding from the coffin lid had detached and fallen over Napoleon's body, covering it like a shroud. Doctor Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body laid comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand laid over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognizable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors. As the body became dehydrated, its hairs started to protrude more and more from the skin, making it look as if the hairs had grown; this being a common phenomenon in well-preserved bodies. In Napoleon's case, this phenomenon was most prominently displayed in what would have been his beard and his chin was stippled with the beginnings of a bluish beard. The hands for their part were very white and the fingers were thin and long; the fingernails were still intact and attached to the fingers and they seemed to have grown longer, also protruding because of the dryness of the skin.

Napoleon wore his famous green uniform of the colonel of chasseurs which was perfectly preserved; his chest was still crossed by the red ribbon of the Légion d'Honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, but all other decorations and medals over the uniform were slightly tarnished. His hat laid sideways across his thighs. The boots he wore had cracked at the seams, showing his four smaller toes in each foot.

All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back. After two minutes' examination, Dr. Guillard proposed that he continue examining the body and open the jars containing the heart and the stomach, in part so that they could confirm or disprove the findings of the autopsy performed by the English when Napoleon died and which had found a perforated ulcer in his stomach. Gourgaud, however, suppressing his tears, became angry and ordered that the coffin be closed at once. The doctor complied and replaced the satin padding, spraying it with a little creosote as a preservative before putting back on the original tin lid (though without re-soldering it) and the original mahogany lid. The original lead coffin was then re-soldered.

The original lead coffin and its contents were then placed into a new ebony coffin with combination lock that had been brought from France. This ebony coffin, made in Paris, was 2.56m long, 1.05m wide and 0.7m deep. Its design imitated classical Roman coffins. The lid bore the sole inscription "Napoléon" in gold letters. Each of the four sides was decorated with the letter N in gilded bronze and there were six strong bronze rings for handles. On the coffin were also inscribed the words "Napoléon Empereur mort à Sainte-Hélène le 05 Mai 1821 (Napoleon, Emperor, died at St Helena on 05 May 1821)".

After the combination lock had been closed, the ebony coffin was placed in a new oak coffin, designed to protect that of ebony. Then this mass, totalling 1,200 kilos, was hoisted by 43 gunners onto a solid hearse, draped in black with four plumes of black feathers at each corner and drawn with great difficulty by four horses caparisoned in black. The coffin was covered with a large (4.3m by 2.8m) black pall made of single piece of velvet sown with golden bees and bearing eagles surmounted by imperial crowns at its corners as well as a large silver cross. The ladies of Saint Helena offered to the French commissioner the tricolour flags that would be used in the ceremony and which they had made with their own hands, and the imperial flag that would be flown by ''Belle Poule''.

All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back. After two minutes' examination, Dr. Guillard proposed that he continue examining the body and open the jars containing the heart and the stomach, in part so that they could confirm or disprove the findings of the autopsy performed by the English when Napoleon died and which had found a perforated ulcer in his stomach. Gourgaud, however, suppressing his tears, became angry and ordered that the coffin be closed at once. The doctor complied and replaced the satin padding, spraying it with a little creosote as a preservative before putting back on the original tin lid (though without re-soldering it) and the original mahogany lid. The original lead coffin was then re-soldered.

The original lead coffin and its contents were then placed into a new ebony coffin with combination lock that had been brought from France. This ebony coffin, made in Paris, was 2.56m long, 1.05m wide and 0.7m deep. Its design imitated classical Roman coffins. The lid bore the sole inscription "Napoléon" in gold letters. Each of the four sides was decorated with the letter N in gilded bronze and there were six strong bronze rings for handles. On the coffin were also inscribed the words "Napoléon Empereur mort à Sainte-Hélène le 05 Mai 1821 (Napoleon, Emperor, died at St Helena on 05 May 1821)".

After the combination lock had been closed, the ebony coffin was placed in a new oak coffin, designed to protect that of ebony. Then this mass, totalling 1,200 kilos, was hoisted by 43 gunners onto a solid hearse, draped in black with four plumes of black feathers at each corner and drawn with great difficulty by four horses caparisoned in black. The coffin was covered with a large (4.3m by 2.8m) black pall made of single piece of velvet sown with golden bees and bearing eagles surmounted by imperial crowns at its corners as well as a large silver cross. The ladies of Saint Helena offered to the French commissioner the tricolour flags that would be used in the ceremony and which they had made with their own hands, and the imperial flag that would be flown by ''Belle Poule''.

Transfer to ''Belle Poule''

At 3.30, in driving rain, with the citadel and ''Belle Poule'' firing alternate gun salutes, the cortège slowly moved along under the command of Middlemore. Count Bertrand, Baron Gourgaud, Baron Las Cases the younger and Marchand walked holding the corners of the pall. A detachment of militia brought up the rear, followed by a crowd of people, while the forts fired their cannon on every minute. Reaching Jamestown, the procession marched between two ranks of garrison soldiers with arms reversed. The French ships lowered their launches, with that of ''Belle Poule'', ornamented with gilded eagles, carrying Joinville. At 5.30 the funeral procession stopped at the end of the jetty. Middlemore, old and ill, walked painfully over to Joinville. Their brief conversation, more or less in French, marked the point at which the remains were officially handed over to France. With infinite caution, the heavy coffin was placed in the launch. The French ships (up until then showing signs of mourning) hoisted their colours and all the ships present fired their guns. On ''Belle Poule'' 60 men were paraded, drums beat a salute and funeral airs were played. The coffin was hoisted onto the deck and its oak envelope was taken off. Coquereau gave absolution and Napoleon had returned to French territory. At 6.30 the coffin was placed in a candlelit chapel, ornamented with military trophies, on the stern of the ship. At 10 the following day mass was said on deck, then the coffin was lowered into the candlelit chapel in the steerage, while the frigate's band played. Once this had been done, each officer received a commemorative medal. The sailors divided up among themselves the oak coffin and the dead willow that had been taken away from the Valley of the Tomb.Return from St Helena

At 8am on Sunday 18 October ''Belle Poule'', ''Favorite'' and ''Oreste'' set sail. ''Oreste'' rejoined the Levant division, whilst the two other ships sailed towards France at full speed, fearful of being attacked. No notable setback occurred to ''Belle Poule'' and ''Favorite'' during the first 13 days of this voyage, though on 31 October they met the merchantman ''Hambourg'', whose captain gave Joinville news of Europe, confirming the news he had received from Doret. The threat of war was confirmed by the Dutch ship ''Egmont'', en route for

At 8am on Sunday 18 October ''Belle Poule'', ''Favorite'' and ''Oreste'' set sail. ''Oreste'' rejoined the Levant division, whilst the two other ships sailed towards France at full speed, fearful of being attacked. No notable setback occurred to ''Belle Poule'' and ''Favorite'' during the first 13 days of this voyage, though on 31 October they met the merchantman ''Hambourg'', whose captain gave Joinville news of Europe, confirming the news he had received from Doret. The threat of war was confirmed by the Dutch ship ''Egmont'', en route for Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

. Joinville was sufficiently worried to summon the officers of both his ships to a council of war, to plan precautions to keep the remains out of harm's way should they meet British warships. He had ''Belle Poule'' prepared for possible battle. So that all the ship's guns could be mounted, the temporary cabins set up to house the commission to Saint Helena were demolished and the dividers between them, as well as their furniture, were thrown into the sea – earning the area the nickname "''Lacédémone''". The crew were frequently drilled and called to action stations. Most importantly, he ordered ''Favorite'' to sail away immediately and make for the nearest French port. Joinville was aware that no British warship would attack the ship carrying the body, but also that they would be unlikely to extend the same generosity to ''Favorite''. He doubted, with good reason, that he would be able to save the corvette if she got within range of an enemy ship, without risking his frigate and its precious cargo. Another hypothesis is that ''Favorite'' was the slower ship and would only have held ''Belle Poule'' back if they had been attacked.

On 27 November ''Belle-Poule'' was only 100 leagues from the coasts of France, without having encountered any British patrol. Nonetheless, her commander and crew continued with their precautions – even though these were now unnecessary, because Anglo-French tension had ceased, after France had had to abandon its Egyptian ally and Thiers had been forced to resign.

Arrival in France

In the meantime, in October 1840, a new ministry nominally presided over by Marshal

In the meantime, in October 1840, a new ministry nominally presided over by Marshal Nicolas Soult

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, 1st Duke of Dalmatia, (; 29 March 1769 – 26 November 1851) was a French general and statesman, named Marshal of the Empire in 1804 and often called Marshal Soult. Soult was one of only six officers in Frenc ...

but in reality headed by François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the a ...

succeeded Thiers's cabinet in an attempt to resolve the crisis Thiers had provoked with the United Kingdom over the Middle East. This new arrangement gave rise to fresh hostile comment in the press as to the "''retour des cendres''":

Fearful of being overthrown thanks to the "''retour''" initiative (the future Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

had just attempted a coup d'État) yet unable to abandon it, the government decided to rush it to a conclusion – as Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

commented, "It was pressed into finishing it." The interior minister, Comte Duchâtel, affirmed that "Whether the preparations are ready or not, the funeral ceremony will take place on 15 December, whatever weather should happen or arise."

Everyone in Paris and its suburbs was conscripted to get the preparations done as quickly as possible, with the coffin's return voyage being faster than expected and internal political problems having caused considerable delays. From the Pont de Neuilly to Les Invalides, papier-mâché structures were set up which would line the funeral procession, though these were slapped together only late on the night before the ceremony.

The funeral carriage itself, resplendently gilded and richly draped, was 10 m high, 5.8m wide, 13 m long, weighed 13 tonnes and was drawn by four groups of four richly caparisoned horses. It had four massive gilded wheels, on whose axles rested a thick tabular base. This supported a second base, rounded at the front and forming a semi-circular platform on which were set a group of genii supporting Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

's crown. At the back of this rose a dais, like an ordinary pedestal, on which stood a smaller pedestal in the shape of a quadrangle. Finally: 14 statues, larger than life and gilded all over, held up a vast shield on their heads, above which was placed a model of Napoleon's coffin; this whole ensemble was veiled in a long purple crêpe, sown with gold bees. The back of the car was made up of a trophy of flags, palms and laurels, with the names of Napoleon's main victories.

To avoid any revolutionary outbreak, the government (which had already insisted on the remains being buried with full military honours in Les Invalides) ordered that the ceremony would be strictly military, dismissing the civil cortège and thus infuriating the law and medical students who were to have formed it. Eventually, the students protested in '' Le National'':

"Children of the new generations, he law and medical students

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

do not understand the exclusive cult that gives in to force of arms, in the absence of the civil institutions that are the foundation of liberty. he students

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

do not prostrate themselves before the spirit of invasion and conquest, but, at the moment when our nationality seems to be demeaned, the schools had wished to pay homage by their presence to the man who was from the outset the energetic and glorious representative of this nationality." The diplomatic corps gathered at the British embassy in Paris and decided to abstain from participating in the ceremony due to their antipathy to Napoleon as well as to Louis-Philippe.

On 30 November ''Belle-Poule'' entered the roadstead of Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

, and six days later the remains were transferred to the steamer ''la Normandie''. Reaching Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

, and then on to Val-de-la-Haye

Val-de-la-Haye () is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France.

Geography

A forestry and light industrial village situated by the banks of the Seine, some southwest of Rouen on the D 51 road. A c ...

, near Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of ...

, where the coffin was transferred to ''la Dorade 3'' for carrying further up the Seine, on whose banks people had gathered to pay homage to Napoleon. On 14 December ''la Dorade 3'' moored at Courbevoie

Courbevoie () is a commune located in the Hauts-de-Seine Department of the Île-de-France region of France. It is in the suburbs of the city of Paris, from the center of Paris. The centre of Courbevoie is situated from the city limits of Par ...

in the northwest of Paris.

Reburial

The date for the reburial was set for 15 December. Victor Hugo evoked this day in his ''Les Rayons et les Ombres'':

:"O frozen sky! and sunlight pure! shining bright in history!

:''Funereal triumph, imperial torch!''

:Let the people's memory hold you forever,

:::Day beautiful as glory,

:::Cold as the tomb

Even as far as London, poems commemorating the event were published; one read in part:

:Ah! Luckless to the nations! Luckless day!

:When from Helena's rock they bore away,

:And gave again to France the mouldering bones

:Of him, beneath whose monarchy the thrones

:Of Earth's huge empires shook-that might one,

:The archon of the world-NAPOLEON!

Despite the temperature never rising above 10 degrees Celsius, the crowd of spectators stretching from the

The date for the reburial was set for 15 December. Victor Hugo evoked this day in his ''Les Rayons et les Ombres'':

:"O frozen sky! and sunlight pure! shining bright in history!

:''Funereal triumph, imperial torch!''

:Let the people's memory hold you forever,

:::Day beautiful as glory,

:::Cold as the tomb

Even as far as London, poems commemorating the event were published; one read in part:

:Ah! Luckless to the nations! Luckless day!

:When from Helena's rock they bore away,

:And gave again to France the mouldering bones

:Of him, beneath whose monarchy the thrones

:Of Earth's huge empires shook-that might one,

:The archon of the world-NAPOLEON!

Despite the temperature never rising above 10 degrees Celsius, the crowd of spectators stretching from the Pont de Neuilly

The Pont de Neuilly (English: Bridge of Neuilly) is a road and rail bridge carrying the Route nationale 13 (N13) and Paris Métro Line 1 which crosses the Seine between the right bank of Neuilly-sur-Seine and Courbevoie and Puteaux on the left b ...

to the Invalides was huge. Some houses' rooftops were covered with people. Respect and curiosity won out over irritation, and the biting cold cooled all restlessness in the crowd. Under pale sunlight after snow, the plaster statues and gilded-card ornaments produced an ambiguous effect upon Hugo: "the niggardly clothing the grandiose". Hugo also wrote:

The cortège arrived at the Invalides around 1:30, and at 2 pm it reached the gate of honour. The king and all France's leading statesmen were waiting in the royal chapel, the Église du Dôme. Joinville was to make a short speech, but nobody had remembered to forewarn him – he contented himself with a sabre salute and the king mumbled a few unintelligible words. '' Le Moniteur'' described the scene as best it could:

The cortège arrived at the Invalides around 1:30, and at 2 pm it reached the gate of honour. The king and all France's leading statesmen were waiting in the royal chapel, the Église du Dôme. Joinville was to make a short speech, but nobody had remembered to forewarn him – he contented himself with a sabre salute and the king mumbled a few unintelligible words. '' Le Moniteur'' described the scene as best it could:

General Atthalin stepped forward, bearing on a cushion the sword that Napoleon had worn at

General Atthalin stepped forward, bearing on a cushion the sword that Napoleon had worn at Austerlitz Austerlitz may refer to:

History

* Battle of Austerlitz, an 1805 victory by the French Grand Army of Napoleon Bonaparte

Places

* Austerlitz, German name for Slavkov u Brna in the Czech Republic, which gave its name to the Battle of Austerlitz an ...

and Marengo, which he presented to Louis-Philippe. The king made a strange, recoiling movement, then turned to Bertrand

Bertrand may refer to:

Places

* Bertrand, Missouri, US

* Bertrand, Nebraska, US

* Bertrand, New Brunswick, Canada

* Bertrand Township, Michigan, US

* Bertrand, Michigan

* Bertrand, Virginia, US

* Bertrand Creek, state of Washington

* Saint-Bert ...

and said: "General, I charge you with placing the Emperor's glorious sword upon his coffin." Overcome with emotion, Bertrand was unable to complete this task, and Gourgaud rushed over and seized the weapon. The king turned to Gourgaud and said: "General Gourgaud, place the Emperor's sword upon the coffin."

In the course of the funeral ceremony, the Paris Opera

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be ...

's finest singers were conducted by Habeneck in a performance of Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

's ''Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

''. The ceremony was more worldly than reverent – the deputies were particularly uncomfortable:

The bearing of the old Marshal Moncey, the governor of the Invalides, somewhat redeemed the impertinence of the court and the politicians. For a fortnight he had been in agony, pressing his doctor to keep him alive at least to complete his role in the ceremony. At the end of the religious ceremony he managed to walk to the catafalque, sprinkled holy water on it and pronounced as the closing words: "And now, let us go home to die".

From 16 to 24 December, the Église des Invalides, illuminated as on the day of the ceremony, remained open to the public. The people had long disbelieved in Napoleon's death and a rumour spread that the tomb was only a cenotaph. It was claimed that on St Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy; and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned. Hugo wrote that, though the actual body was there, the people's good sense was not amiss:

The bearing of the old Marshal Moncey, the governor of the Invalides, somewhat redeemed the impertinence of the court and the politicians. For a fortnight he had been in agony, pressing his doctor to keep him alive at least to complete his role in the ceremony. At the end of the religious ceremony he managed to walk to the catafalque, sprinkled holy water on it and pronounced as the closing words: "And now, let us go home to die".

From 16 to 24 December, the Église des Invalides, illuminated as on the day of the ceremony, remained open to the public. The people had long disbelieved in Napoleon's death and a rumour spread that the tomb was only a cenotaph. It was claimed that on St Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy; and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned. Hugo wrote that, though the actual body was there, the people's good sense was not amiss:

Political failure

The return of the remains had been intended to boost the image of the July Monarchy and to provide a tinge of glory to its organisers, Thiers and Louis-Philippe. Thiers had spotted the rise of the French infatuation with the First Empire that would go on to become the Napoleonic myth. He also thought that returning the remains would seal the new spirit of accord between France and the United Kingdom even though the Egyptian affair was beginning to agitate Europe. As for Louis-Philippe he would be disappointed in his hope to use the remains' return to give additional legitimacy to his monarchy, which was rickety and indifferent to the French people. The great majority of the French, excited by the return of the remains of one whom they had come to see as a martyr, felt betrayed that they had been unable to render him the homage that they had wished. Hence, the government began to fear rioting and took every possible measure to prevent the people from assembling. Accordingly, the cortège had been mostly riverborne and had spent little time in towns outside Paris. In Paris, only important personages were present at the ceremony. Worse, the lack of respect shown by most of the politicians shocked public opinion and revealed a rift between the people and their government. The "retour" also did not prevent France from losing its diplomatic war with the United Kingdom. France was forced to give up supporting its Egyptian ally. Thiers, losing his way in aggressive policies, was ridiculed, and the king was compelled to dismiss him even before ''Belle Poule'' arrived. Thiers had managed to push through the return of the remains but was unable to profit from that success.Monument

In April 1840 the organized a competition in which 81 architects participated, whose projects were exhibited in the recently completedPalais des Beaux-Arts