A resident minister, or resident for short, is a

government official

An official is someone who holds an office (function or mandate, regardless whether it carries an actual working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority, (either their own or that of their su ...

required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has

diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of

indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of governance used by the British and others to control parts of their colonial empires, particularly in Africa and Asia, which was done through pre-existing indigenous power structures. Indirect rule was used by vario ...

.

A resident usually heads an administrative area called a

residency

Residency may refer to:

* Domicile (law), the act of establishing or maintaining a residence in a given place

** Permanent residency, indefinite residence within a country despite not having citizenship

* Residency (medicine), a stage of postgrad ...

. "Resident" may also refer to

resident spy A resident spy in the world of espionage is an agent operating within a foreign country for extended periods of time. A base of operations within a foreign country with which a resident spy may liaise is known as a "station" in English and a (, 're ...

, the chief of an

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

operations base.

Resident ministers

This full style occurred commonly as a

diplomatic rank

Diplomatic rank is a system of professional and social rank used in the world of diplomacy and international relations. A diplomat's rank determines many ceremonial details, such as the order of precedence at official processions, table seating ...

for the head of a mission ranking just below

envoy

Envoy or Envoys may refer to:

Diplomacy

* Diplomacy, in general

* Envoy (title)

* Special envoy, a type of diplomatic rank

Brands

*Airspeed Envoy, a 1930s British light transport aircraft

*Envoy (automobile), an automobile brand used to sell Br ...

, usually reflecting the relatively low status of the states of origin and/or residency, or else difficult relations.

On occasion, the resident minister's role could become extremely important, as when in 1806 the Bourbon king

Ferdinand IV fled his

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, and

Lord William Bentinck

Lieutenant General Lord William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (14 September 177417 June 1839), known as Lord William Bentinck, was a British soldier and statesman who served as the Governor of Fort William (Bengal) from 1828 to 1834 and the First G ...

, the British Resident, authored (1812) a new and relatively liberal constitution.

Residents could also be posted to nations which had significant foreign influence. For instance, the British sent residents to the

Mameluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

Beys who ruled

Baghdad province as an autonomous state (17041831) in the north of present-day

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, until the

Ottoman sultans reasserted control over it (1831) and its

Wali

A wali (''wali'' ar, وَلِيّ, '; plural , '), the Arabic word which has been variously translated "master", "authority", "custodian", "protector", is most commonly used by Muslims to indicate an Islamic saint, otherwise referred to by the ...

(governor). After the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

restored the

Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany ( it, Granducato di Toscana; la, Magnus Ducatus Etruriae) was an Italian monarchy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1859, replacing the Republic of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In th ...

in 1815, the British posted a resident to

Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

to handle their affairs there.

As international relations developed, it became customary to give the highest title of diplomatic rank –

ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

– to the head of all permanent missions in any country, except as a temporary expression of down-graded relations or where representation was merely an interim arrangement.

Pseudo-colonial residents

Some official representatives of European colonial powers, while in theory diplomats, in practice exercised a degree of

indirect control. Some such residents were former military officers, rather than career diplomats, who resided in smaller self-governing

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

s and

tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

s and acted as political advisors to the ruler. A trusted resident could even become the ''de facto'' prime minister to a native ruler. In other respects they acted as an ambassador of the government of the country they were posted to, but at a lower level, since they were protectorates or tributaries of Western nations. Instead of being a representative to a single ruler, a resident could be posted to more than one native state, or to a grouping of states which the European power decided for its convenience. This could create an artificial geographical unit, as in Residency X in some parts of the

Indian Empire

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

. Similar positions could carry alternative titles, such as

political agent and

resident commissioner

Resident commissioner was or is an official title of several different types of commissioners, who were or are representatives of any level of government. Historically, they were appointed by the British Crown in overseas protectorates (such ...

.

In some cases, the intertwining of the European power with the traditional native establishment went so far that members of the native princely houses became residents, either in other states or even within their own state, provided that they were unlikely ever to succeed as ruler of the state. A resident's real role varied enormously, depending upon the underlying relationship between the two parties and even upon the personalities of the Resident and the ruler. Some residents were little more than observers and diplomats, others were seen as unwanted interlopers and were treated with hostility, while some won enough trust from the ruler that they were able to exercise great influence. In French protectorates, such as those of Morocco and Tunisia, the resident or resident general was the effective ruler of the territory. In 1887, when both

Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

s and gold prospectors of all nationalities were overrunning his country, the Swazi

paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a chief-based system. This term is used occasionally in anthropological and arch ...

Umbandine asked for a British resident, seeing this as a desirable and effective form of protection. His request was refused.

British and dominion residents

The residents of the governments of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the

dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s to a variety of protectorates include:

Residents in Africa

* In the Sultanate of

Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

, the second 'homeland' of the Omani dynasty, since 1913. From 1913 to 1961 the Residents were also the Sultan's

vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

. There were Consuls and Consuls-general until 1963.

* In present-day

Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

, in the Sultanate of

Witu, after the British took over the protectorate from the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, which had itself posted a Resident.

* In

British Cameroon

British Cameroon or the British Cameroons was a British mandate territory in British West Africa, formed of the Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons. Today, the Northern Cameroons forms parts of the Borno, Adamawa and Taraba states of N ...

(part of the former German Kamerun), since 1916, in 1949 restyled Special Resident (superior to the new two provinces) for Edward John Gibbons (b. 1906 – d. 1990), who stayed on in October 1954 as first Commissioner when it became an autonomous part of

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

.

* in Southern Africa:

** when the military party sent from Cape Colony to occupy Port Natal on behalf of Great Britain was recalled in 1839, a British Resident was appointed among the

Fingo and other tribes in

Kaffraria

Kaffraria was the descriptive name given to the southeast part of what is today the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Kaffraria, i.e. the land of the Kaffirs, is no longer an official designation (with the term ''kaffir'' now an offensive racial sl ...

until the definite establishment of British rule in Natal and its 1845 organization as an administrative entity, when the incumbent Shepstone was made Agent for the native tribes.

** In

kwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuth ...

, which since 1843 was under a British protectorate, after it became the Zulu "Native" Reserve or Zululand Province on 1 September 1879: two British Residents (William Douglas Wheelwright, 8 September 1879 to January 1880, then Sir Melmoth Osborn until 22 December 1882). Thereafter there were Resident Commissioners until Zululand was incorporated into the

crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

of

Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

as British Zululand on 1 December 1897.

** in 1845 the resident 'north of the Orange river' chose his residency at

Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein, ( ; , "fountain of flowers") also known as Bloem, is one of South Africa's three capital cities and the capital of the Free State (province), Free State province. It serves as the country's judicial capital, along with legisla ...

, which became the capital of the

Orange River Sovereignty

The Orange River Sovereignty (1848–1854) was a short-lived political entity between the Orange and Vaal rivers in Southern Africa, a region known informally as Transorangia. In 1854, it became the Orange Free State, and is now the Free State ...

in 1848. In 1854 the British abandoned the Sovereignty, and the independent Boer republic of the

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

was established

** in the

Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

republic of

Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

at Pretoria

** with the

Matabele chief at

Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council cl ...

* in

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, with the rulers of the

Asanteman Confederation

The Asante Empire ( Asante Twi: ), today commonly called the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted between 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana. It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana as well as parts of ...

(established in 1701), since it became in 1896 a British protectorate; on 23 June 1900 the Confederation was dissolved by UK protectorate authority, on 26 September 1901 turned into

Ashanti Colony

Ashanti may refer to:

* Ashanti people, an ethnic group in West Africa

** Ashanti Empire, a pre-colonial West African state in what is now southern Ghana

** Ashanti dialect or Asante, a literary dialect of the Akan language of southern Ghana

** ...

, so since 1902 his place was taken by a

Chief Commissioner

A chief commissioner is a commissioner of a high rank, usually in chief of several commissioners or similarly styled officers.

Colonial

In British India the gubernatorial style was chief commissioner in various (not all) provinces (often after be ...

at

Kumasi

Kumasi (historically spelled Comassie or Coomassie, usually spelled Kumase in Twi) is a city in the Ashanti Region, and is among the largest metropolitan areas in Ghana. Kumasi is located in a rain forest region near Lake Bosomtwe, and is the ...

* in various parts of the

Northern Nigeria Protectorate

Northern Nigeria (Hausa: ''Arewacin Najeriya'') was a British protectorate which lasted from 1900 until 1914 and covered the northern part of what is now Nigeria.

The protectorate spanned and included the emirates of the Sokoto Caliphate an ...

,

Southern Nigeria Protectorate

Southern Nigeria was a British protectorate in the coastal areas of modern-day Nigeria formed in 1900 from the union of the Niger Coast Protectorate with territories chartered by the Royal Niger Company below Lokoja on the Niger River.

The ...

and after their joining Nigeria protectorate, notably in

Edo state

Edo, commonly known as Edo State, is a state located in the South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria. As of 2006 National population census, the state was ranked as the 24th populated state (3,233,366) in Nigeria, However there was controversy ...

at

Benin City

Benin City is the capital and largest city of Edo State, Edo State, Nigeria. It is the fourth-largest city in Nigeria according to the 2006 census, after Lagos, Kano (city), Kano, and Ibadan, with a population estimate of about 3,500,000 as of ...

(first to the British-installed ruling council of chiefs, later to the restored Oba), with the Emir of and in

Bauchi

Bauchi (earlier Yakoba) is a city in northeast Nigeria, the Administrative center of Bauchi State, of the Bauchi Local Government Area within that State, and of the traditional Bauchi Emirate. It is located on the northern edge of the Jos Plateau ...

, to the jointly ruling

bale and balogun of

Ibadan

Ibadan (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Oyo State, in Nigeria. It is the third-largest city by population in Nigeria after Lagos and Kano, with a total population of 3,649,000 as of 2021, and over 6 million people within its me ...

(a vassal state in

Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

land), with the Emir of

Illorin

Ilorin is the capital city of Kwara State in Western Nigeria.. Retrieved 18 February 2007 As of the 2006 census, it had a population of 777,667, making it the 7th largest city by population in Nigeria.

History

Ilorin was founded by the ...

, with the Emir of and in

Muri (Nigeria), with the Emir of

Nupe Nupe may refer to:

*Nupe people, of Nigeria

*Nupe language, their language

*The Bida Emirate, also known as the Nupe Kingdom, their former state

*A member of the Kappa Alpha Psi

Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. () is a historically African Amer ...

Residents in Asia

British residents were posted in various

princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

s – in major states or groups of states—in the days of

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

.

Often they were appointed to a single state, as with the Resident in

Lucknow

Lucknow (, ) is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is also the second largest urban agglomeration in Uttar Pradesh. Lucknow is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous district and division ...

, the capital of

Oudh

The Oudh State (, also Kingdom of Awadh, Kingdom of Oudh, or Awadh State) was a princely state in the Awadh region of North India until its annexation by the British in 1856. The name Oudh, now obsolete, was once the anglicized name of ...

; to the Maharaja Gaekwar of

Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

; to the Maharaja Sindhya of

Gwalior

Gwalior() is a major city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh; it lies in northern part of Madhya Pradesh and is one of the Counter-magnet cities. Located south of Delhi, the capital city of India, from Agra and from Bhopal, the s ...

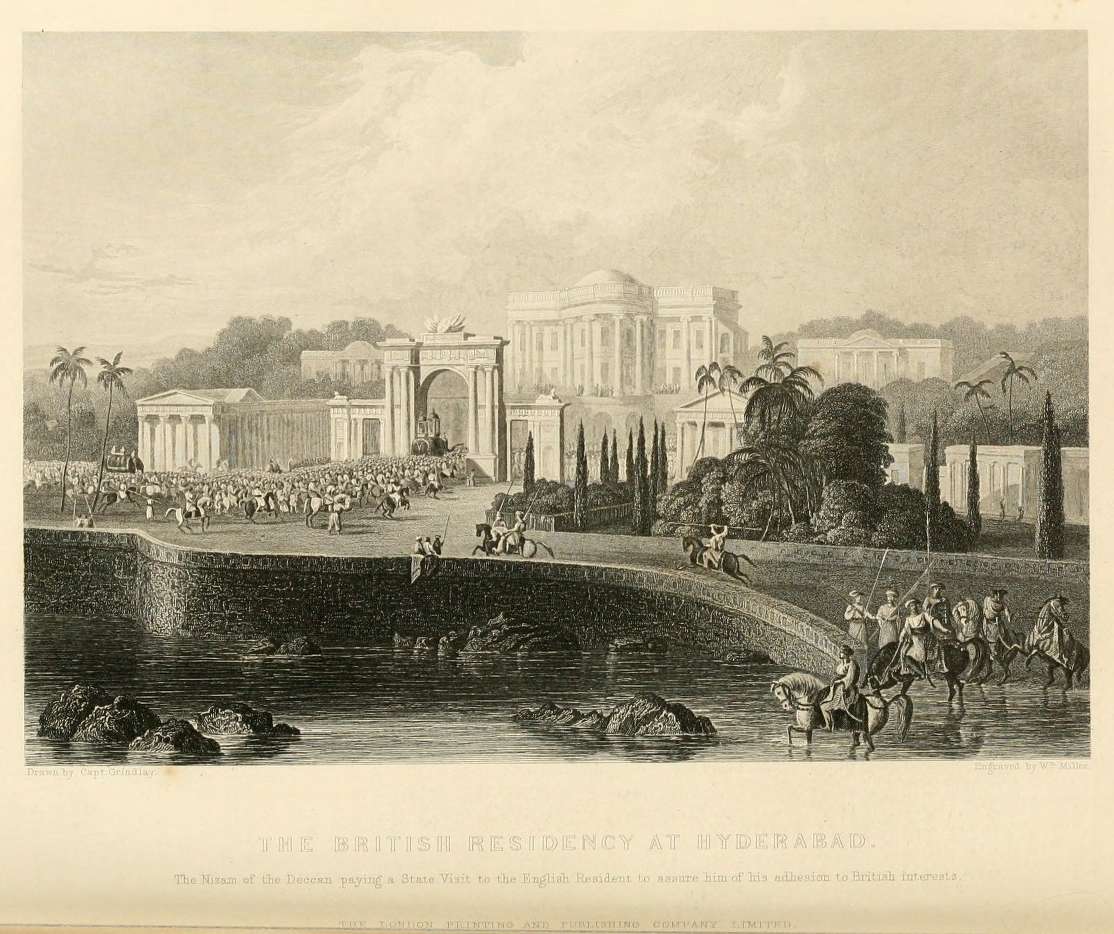

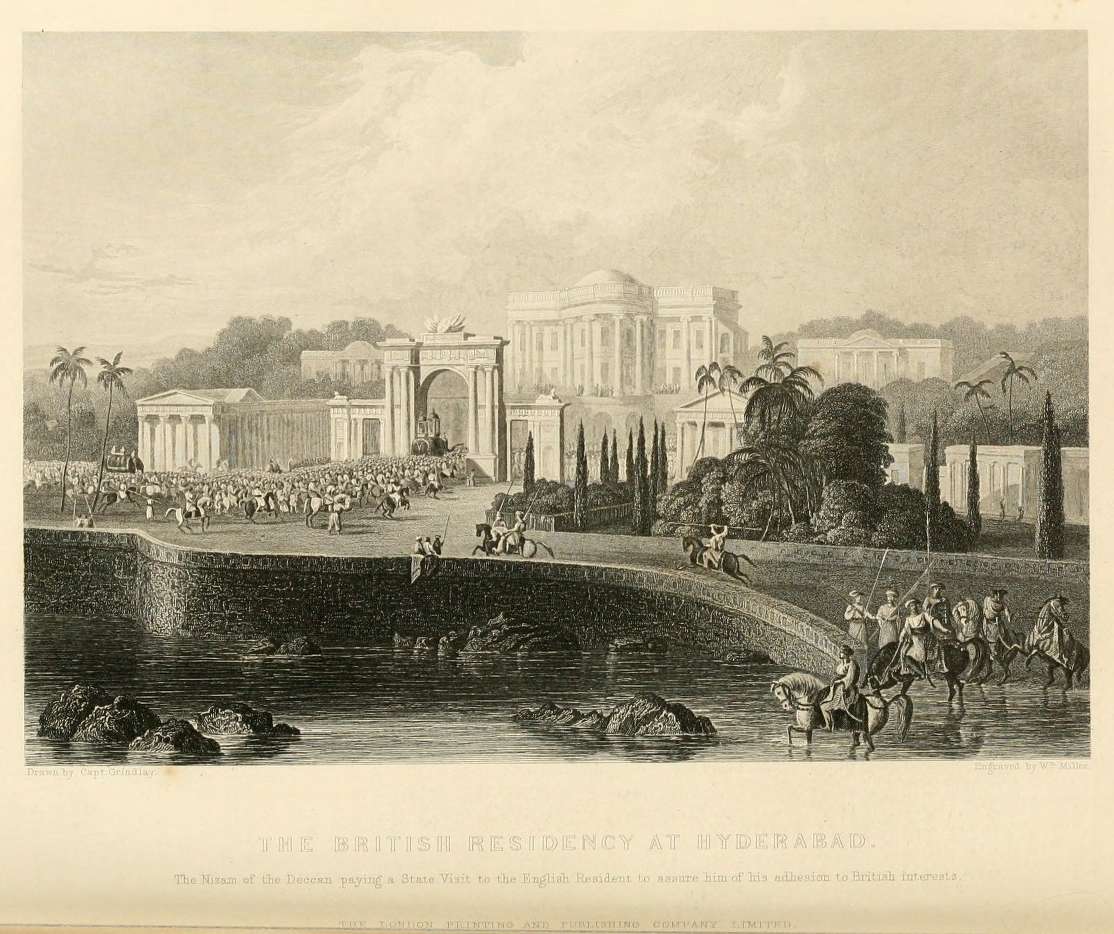

; to the Nizam al-Mulk of

Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

; to the Maharaja Rana of

Jhalawar

Jhalawar () is a city, municipal council and headquarter in Jhalawar district of the Indian state of Rajasthan. It is located in the southeastern part of the state. It was the capital of the former princely state of Jhalawar, and is the admin ...

; to the restored Maharaja of

Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude of ...

, after the fall of

Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He int ...

; to the Maharaja Sena Sahib Subah of the Mahratta state of

Nagpur

Nagpur (pronunciation: Help:IPA/Marathi, aːɡpuːɾ is the third largest city and the winter capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the 13th largest city in India by population and according to an Oxford's Economics report, Nag ...

; to the (Maha)Raja of

Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of Myanm ...

; to the (Maha)Raja of

Travancore

The Kingdom of Travancore ( /ˈtrævənkɔːr/), also known as the Kingdom of Thiruvithamkoor, was an Indian kingdom from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. At ...

; to the Maharana of

Mewar

Mewar or Mewad is a region in the south-central part of Rajasthan state of India. It includes the present-day districts of Bhilwara, Chittorgarh, Pratapgarh, Rajsamand, Udaipur, Pirawa Tehsil of Jhalawar District of Rajasthan, Neemuch and Man ...

in Udaipur.

Even when

Lord Lake

Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (27 July 1744 – 20 February 1808) was a British general. He commanded British forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and later served as Commander-in-Chief of the military in British India.

Background

He was ...

had broken the

Mahratta power in 1803, and the

Mughal emperor

The Mughal emperors ( fa, , Pādishāhān) were the supreme heads of state of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. The Mughal rulers styled t ...

was taken under the protection of the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

, the districts of

Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

and

Hissar were assigned for the maintenance of the royal family, and were administered by a British Resident, until in 1832 the whole area was annexed to

British Residents were also posted in major states considered to be connected with India, neighbouring or on the sea route to it, notably:

* in

Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

[ (while subordinated to the ]Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency or Bombay Province, also called Bombay and Sind (1843–1936), was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India, with its capital in the city that came up over the seven islands of Bombay. The first mainl ...

), the only part of the present-day Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

made a colony in full British possession. The last of three British Political Agents since 1939 stayed on as first Resident since 1859, the last again staying on in 1932 as first Chief Commissioner; he was the only diplomatic representative to the various Arabian rulers who over time accepted British protectorate, but since the 1935 legal separation from British India was followed in 1937 by a reorganisation into an Eastern and a Western Aden Protectorate (based at Mukallah and Lahej; together covering all Yemen), the British Representatives in each were styled British Political officers

* in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, a kingdom entitled to a gun salute

A gun salute or cannon salute is the use of a piece of artillery to fire shots, often 21 in number (''21-gun salute''), with the aim of marking an honor or celebrating a joyful event. It is a tradition in many countries around the world.

Histo ...

of 21 guns (the highest rank among princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

s, not then among Sovereign monarchs): the first British Residents were Sir Alexander Burnes (1837 – 2 November 1841); William Hay McNaghten (7 August 1839 – 23 December 1841); Eldred Pottinger (December 1841 – 6 January 1842). After that, four native ''Vakil

''Vakil'' was one of the highest positions in the hierarchy of Safavid Iran, denoting the viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term der ...

''s acted on behalf of the British government: Nawab Foujdar Khan (1856 – April 1859), Ghulam Husain Khan Allizai (April 1859 – 1865), Bukhiar Khan (February 1864 – January 1868, acting), Attah Muhammad Khan Khagwani (January 1868 – 1878); then there were two more British Residents Louis Napoleon Cavagnari (24 July 1879 – 3 September 1879), Henry Lepel-Griffin (1880); next came two Military Commanders (8 October 1879 – 11 August 1880) and until 1919 ten native British Agents, one of whom served two non-consecutive terms.

* Capt. Hiram Cox Captain Hiram Cox (1760–1799) was a British diplomat, serving in Bengal and Burma in the 18th century. The city of Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh is named after him.

Biography

As an officer of the East India Company, Captain Cox was appointed Supe ...

(died 1799) was the first British Resident to the King of independent Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

(October 1796 – July 1797), and there were more discontinuous posting to that court, in the 19th century, never satisfactory to either party; after the Third Anglo-Burmese War

The Third Anglo-Burmese War ( my, တတိယ အင်္ဂလိပ် – မြန်မာစစ်, Tatiya Anggalip–Mran cac), also known as the Third Burma War, took place during 7–29 November 1885, with sporadic resistance conti ...

there were two separate British Residents in a border zone of that country: in the Northern Shan States and in the Southern Shan States

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

(each several tribal states, usually ruled by a Saopha

Chao-Pha (; Ahom language, Tai Ahom: 𑜋𑜧𑜨 𑜇𑜡, th, เจ้าฟ้า}, shn, ၸဝ်ႈၾႃႉ, translit=Jao3 Fa5 Jao3 Fa5, my, စော်ဘွား ''Sawbwa,'' ) was a royal title used by the hereditary rulers of the T ...

=Sawbwa

Chao-Pha (; Tai Ahom: 𑜋𑜧𑜨 𑜇𑜡, th, เจ้าฟ้า}, shn, ၸဝ်ႈၾႃႉ, translit=Jao3 Fa5 Jao3 Fa5, my, စော်ဘွား ''Sawbwa,'' ) was a royal title used by the hereditary rulers of the Tai peoples of ...

) in 1945–1948 (each group had been under a Superintendent from 1887/88 till 1922, then both jointly under a Resident Commissioner till the 1942 Japanese occupation)

* after five military governors since the East India Company started chasing the Dutch out of Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

in August 1795 and occupying the island (completed on 16 February 1796), their only Resident there was Robert Andrews, 12 February 1796 – 12 October 1798, who was subordinate to the presidency of Madras

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, also known as Madras Province, was an Presidencies and provinces of British India, administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency in ...

(see British India), afterwards the HEIC

High Efficiency Image File Format (HEIF) is a container format for storing individual digital images and image sequences. The standard covers multimedia files that can also include other media streams, such as timed text, audio and video.

HEIF ...

appointed Governors as it was made a separate colony

* to the Sultan of the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

archipelago since he formally accepted British protection on 16 December 1887 (informally since 1796, after the British took over Ceylon from the Dutch), but in fact this office was filled ''ex officio'' by the colonial Governors of until 4 February 1948, abolished on 26 July 1965

* in Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

[ since 1802, accredited to the Hindu Kings (title ]Maharajadhiraja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

), since 15 March 1816 exercising a de facto protectorate—the last staying on 1920 as Envoy

Envoy or Envoys may refer to:

Diplomacy

* Diplomacy, in general

* Envoy (title)

* Special envoy, a type of diplomatic rank

Brands

*Airspeed Envoy, a 1930s British light transport aircraft

*Envoy (automobile), an automobile brand used to sell Bri ...

till the 1923 emancipation

* with the Imam/Sultan of Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

, 1800–1804, 1805–1810 and 1840 (so twice interrupted by vacancy), then located with the African branch of the dynasty on the island of Unguja, since 1862 his role was handed over to a Political Agent

And elsewhere:

* in Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

(present Jordan) April 1921 – 17 June 1946 four incumbents accredited to the Hashemite Emir/King

Even in overseas territories occupied ('preventively' or conquered) to keep the French out of strategic trade and waters, residencies could be established, e.g. at Laye on Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, an island returned to the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

Residents in (British) European protectorates

Since on 5 November 1815 the United States of the Ionian Islands

The United States of the Ionian Islands ( el, Ἡνωμένον Κράτος τῶν Ἰονίων Νήσων, Inoménon-Krátos ton Ioníon Níson, United State of the Ionian Islands; it, Stati Uniti delle Isole Ionie) was a Greek state and am ...

became a federal republic of seven islands (Corfu, Cephalonia, Zante, Santa Maura, Ithaca, Cerigo and Paxos), as a protectorate (nominally of the allied Powers; de facto UK protectorate; the highest office was the always-British Lord High Commissioner), until its 1 June 1864 incorporation into independent Greece, there were British residents, each posted with a local Prefect, on seven individual islands, notably: Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It i ...

(Kephalonia), Cerigo

Kythira (, ; el, Κύθηρα, , also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira) is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands, ...

(Kythira), Ithaca

Ithaca most commonly refers to:

*Homer's Ithaca, an island featured in Homer's ''Odyssey''

*Ithaca (island), an island in Greece, possibly Homer's Ithaca

*Ithaca, New York, a city, and home of Cornell University and Ithaca College

Ithaca, Ithaka ...

, Paxos

Paxos ( gr, Παξός) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, lying just south of Corfu. As a group with the nearby island of Antipaxos and adjoining islets, it is also called by the plural form Paxi or Paxoi ( gr, Παξοί, pronounced in Engl ...

, Santa Maura

Lefkada ( el, Λευκάδα, ''Lefkáda'', ), also known as Lefkas or Leukas (Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: Λευκάς, ''Leukás'', modern pronunciation ''Lefkás'') and Leucadia, is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea on the west coast of ...

(Leucada/Lefkada) and Zante

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; el, Ζάκυνθος, Zákynthos ; it, Zacinto ) or Zante (, , ; el, Τζάντε, Tzánte ; from the Venetian form) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands. Za ...

(Zakynthos)

Residents on (British and dominion) ocean island states

* in the early colonial settlement phase on

* in the early colonial settlement phase on New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

(where the Polynesian Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

declared independence on 28 October 1835 as the Confederation of the United Tribes, under a British protectorate), from 10 May 1833 James Busby

James Busby (7 February 1802 – 15 July 1871) was the British Resident in New Zealand from 1833 to 1840. He was involved in drafting the 1835 Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. As British Resident, ...

(b. 1801 – d. 1871; from 1834 to 1836 jointly with Thomas McDonnell as ''co-resident'') till 28 January 1840, then two lieutenant governors (as part of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, in Australia) and many governors since 3 January 1841

* at Rarotonga

Rarotonga is the largest and most populous of the Cook Islands. The island is volcanic, with an area of , and is home to almost 75% of the country's population, with 13,007 of a total population of 17,434. The Cook Islands' Parliament buildings a ...

since the 1888 establishment of the British protectorate over the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

; the third and last incumbent stayed on as first Resident Commissioner since 1901, at the incorporation in the British Western Pacific Territories (under a single High Commissioner, till its 1976 dissolution, in Suva or Honoria), until the abolition of the post at the 1965 self-government grant as territory in free association with New Zealand, having its own cabinet (still under the British Crown, which after the 1976 appoints a special King's/Queen's Representative, as well as a High Commissioner).

Residents in protectorates of decolonised Commonwealth states

* Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

, where the Maharaja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

had been under a British protectorate (1861 – 15 August 1947; the crown representative was styled Political Agent), became immediately afterwards a protectorate of newly independent India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(formally from 5 December 1950; in the meantime the Indian representative was again styled Political Agent, the first incumbent actually being the former British Political Agent—India was a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

, still under the British crown, till 26 January 1950) until 16 May 1975, it was annexed as a constituent state of India.

Dutch colonial residents

In the

In the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

, Dutch residents and lower ranks such as assistant residents were posted alongside a number of the many native princes in present Indonesia, compare Regentschap.

For example, on Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, there were Dutch residents at Palembang

Palembang () is the capital city of the Indonesian province of South Sumatra. The city proper covers on both banks of the Musi River on the eastern lowland of southern Sumatra. It had a population of 1,668,848 at the 2020 Census. Palembang ...

, at Medan

Medan (; English: ) is the capital and largest city of the Indonesian province of North Sumatra, as well as a regional hub and financial centre of Sumatra. According to the National Development Planning Agency, Medan is one of the four main ...

in Deli sultanate

Sultanate of Deli ( Indonesian: ''Kesultanan Deli Darul Maimoon''; Jawi: ) was a 1,820 km² Malay state in east Sumatra founded in 1630. A tributary kingdom from 1630 it was controlled by various Sultanates until 1814, when it became an ...

; another was posted with the Sultan of and on Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the we ...

, and one in Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and Nu ...

.

French colonial residents

France also maintained residents, the French word being ''résident''.

However the 'Jacobin' tradition of strict state authority didn't agree well with indirect rule, so often direct rule was preferred.

Many were part of a white colonial hierarchy, rather than truly posted with a native ruler or chieftain.

Style ''résident''

* A single post of resident was also created in ''Côte d'Ivoire'', i.e. Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

(from 1881 subordinated to the Superior Commandant of Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

and the Gulf of Guinea Settlements; from 1886 subordinated to the Lieutenant Governors of Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

), where in 1842 France had declared protectorates over the Kingdoms of Nzima and Sanwi

Kingdom of Sanwi is a traditional kingdom located in the south-east corner of the Republic of Ivory Coast in West Africa. It was established in about 1740 by Anyi migrants from Ghana. In 1843 the kingdom became a protectorate of France. In 1959 i ...

(posts at Assinié 1843–1870, and Grand Bassam, Fort Dabou 1853–1872, part of the Colony of Gorée and Dependencies in Senegal]):

** 1871–1885 Arthur Verdier (to 1878 Warden of the French Flag) (b. 1835 – d. 1898)

** 1885–1886 Charles Bour -Commandant-particular

** 1886 – 9 March 1890 Marcel Treich Leplène (b. 1860 – d. 1890)

** 9 March 1890 – 14 June 1890 Jean Joseph Étienne Octave Péan (acting)

** 14 June 1890 – 1892 Jean Auguste Henri Desailles

** 1892 Éloi Bricard (acting)

** 1892 – 12 November 1892 Julien Voisin (acting)

** 12 November 1892 – 10 March 1893 Paul Alphonse Frédéric Heckman; thereafter it had its own Governors

* On the Comoros

The Comoros,, ' officially the Union of the Comoros,; ar, الاتحاد القمري ' is an independent country made up of three islands in southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. It ...

, in the Indian Ocean, several Residents were posted with the various native sultanates

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

on major islands; they were all three subordinated to the French administrators of Mayotte

Mayotte (; french: Mayotte, ; Shimaore: ''Maore'', ; Kibushi: ''Maori'', ), officially the Department of Mayotte (french: Département de Mayotte), is an overseas department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is loc ...

island protectorate (itself constituting the native Maore or Mawuti sultanate):

** On Ngazidja (Grande Comore

Grande Comore () is an island in Comoros off the coast of Africa. It is the largest island in the Comoros nation. Most of its population is of the Comorian ethnic group. Its population is about 316,600. The island's capital is Moroni, Comoros, ...

island, divided in eleven sultanates, some of which on occasion had the superior title of Sultani tibe

Several sultanates on the Comoros, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean with an ethnically complex mix, were founded after the introduction of Islam into the area in the 15th century. Other uses depending on the island could also be styled ''fani ...

): November 1886 – 1912

** On Ndzuwani (Anjouan

Anjouan (; also known as Ndzuwani or Nzwani, and historically as Johanna or Hinzuan) is an autonomous high island in the Indian Ocean that forms part of the Union of the Comoros. Its chief town is Mutsamudu and, , its population is around 277,500. ...

island) with the Phany (sole Sultan): only two incumbents 188x–189x

** On Mwali (Mohéli

Mohéli , also known as Mwali, is an autonomous island that forms part of the Comoros, Union of the Comoros. It is the smallest of the three major islands in the country. It is located in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Africa and it is the sma ...

island) from 1886; then 1889–1912 filled by the above résidents of Anjouan

* On Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (; french: Wallis-et-Futuna or ', Fakauvea and Fakafutuna: '), is a French island collectivity in the South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji ...

, after a single French Representative styled ''chargé de mission'' (7 April 1887 – 26 June 1888, Maurice Antoine Chauvot), there was a long list of Residents from 7 April 1887; since 3 October 1961, when both islands were joined as the Wallis & Futuna overseas territory, their successors were styled ''Administrateur supérieur'' 'Administrator-superior', but the native dynasties remain; they represented the French government by virtue of the protectorate treaties with the Tui (ruler) of 'Uvea (Wallis island, 5 April 1887; 27 November 1887 administratively attached to New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

) and on 16 February 1888 with the two kingdoms on Futuna—Tu`a

Alo (also known unofficially as Tu`a or the Kingdom of Futuna) is one of three official chiefdoms of the French territory of Wallis and Futuna, in Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. (The other two chiefdoms are Uvea and Sigave.)

Geography

Ove ...

(also called Alo) and Sigave

Sigavé (also Singave or Sigave) is one of the three official chiefdoms of the French territory of Wallis and Futuna in Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. (The other two chiefdoms are Uvea and Alo.)

Geography Overview

Sigave encompasses the wes ...

''Résident supérieur''

This French title, meaning "Superior" (i.e. Senior) Resident, indicates that he had junior Residents under him.

*In Upper Volta (present Burkina Faso), which has had its own Lieutenant governor (before) or Governor (after) and intermediately has been part of one or (carved up) more neighbouring French colonies, there has been one Résident-Superieur of "Upper Ivory Coast", 1 January 1938 – 29 July 1940, while it was part of the Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

colony: Edmond Louveau

*In Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

, where the local royal government was theoretically maintained, the resident at Phnom-Penh was the Resident-Superior, over the various Residents posted throughout Cambodia. The Resident-Superior of Cambodia answered to the Governor-General of Indochina, however.

German colonial residents

In the German colonies, the title was also Resident; the post was called ''Residentur''.

* in Wituland

Wituland (also Witu, Vitu, Witu Protectorate or Swahililand) was a territory of approximately in East Africa centered on the town of Witu just inland from Indian Ocean port of Lamu north of the mouth of the Tana River in what is now Kenya.

Hist ...

: Ahmed ibn Fumo Bakari, the first mfalume (sultan) of Witu (on the Kenyan coast), ceded of territory on 8 April 1885 to the brothers Clemens and Gustav Denhardt's "Tana Company", and the remainder of the Wituland became the German ''Schutzgebiet

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

'' (Protectorate) of Wituland

Wituland (also Witu, Vitu, Witu Protectorate or Swahililand) was a territory of approximately in East Africa centered on the town of Witu just inland from Indian Ocean port of Lamu north of the mouth of the Tana River in what is now Kenya.

Hist ...

(''Deutsch-Witu'') on 27 May 1885. The Reich was represented there by the German Residents: Gustav Denhardt (b. 1856 – d. 1917; in office 8 April 1885 – 1 July 1890) and his deputy Clemens Andreas Denhardt (b. 1852 – d. 1928) until on 1 July 1890 imperial Germany renounces its protectorate, ceding the Wituland to Great Britain which had on 18 June 1890 declared it a British protectorate).

* in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozam ...

** Resident of Ruanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equato ...

: 1906 – 15 November 1907 Werner von Grawert (d. 1918), formerly the last military district commander of Usumbura (the other district being Ujiji)

** Resident of Urundi

Burundi (, ), officially the Republic of Burundi ( rn, Repuburika y’Uburundi ; Swahili: ''Jamuhuri ya Burundi''; French: ''République du Burundi'' ), is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Gre ...

(present Burundi): 15 November 1907 – June 1916, starting with the same as above; formally accredited to the native Mwami (King; on 8 October 1905 the Germans recognized the already ruling Mwezi IV Gisabo as "Sultan" of Burundi and its only supreme authority)

** Resident of Bukoba

Bukoba is a city with a population of 128,796 (2012 census), situated in the north west of Tanzania on the south western shores of Lake Victoria. It is the capital of the Kagera region, and the administrative seat for Bukoba Urban District.

T ...

west of Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface area after ...

overseeing an area of 32,200 km2;

* in German Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern p ...

** Resident of Garua

** Resident of Mora

Mora may refer to:

People

* Mora (surname)

Places Sweden

* Mora, Säter, Sweden

* Mora, Sweden, the seat of Mora Municipality

* Mora Municipality, Sweden

United States

* Mora, Louisiana, an unincorporated community

* Mora, Minnesota, a city

* M ...

** Resident of Ngaundere

* in German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

(present Namibia)

** Resident of Schuckmannsburg for the Caprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is surrounded by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a sin ...

.

Portuguese colonial residents

* In Cabinda (in present Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

), five incumbents from 1885 (18 July 1885 Portuguese Congo district created after 14 February 1885 confirmation by the Berlin Conference of the 1883 Portuguese protectorate over "Portuguese Congo") to 1899 (end of autonomy under the Governors of Congo district which had its seat in Cabinda since 1887)

* In the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá

The Forte de São João Baptista de Ajudá (in English: ''Fort St. John the Baptist of Ouidah'') is a small restored fort in Ouidah, Benin. Built in 1721, it was the last of three European forts built in that town to tap the slave trade of the ...

(in present Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north ...

), country that was named Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

until 1975, civil residents served from 1911 (withdrawal of the Portuguese military garrison) until 31 July 1961 (invasion of the fort by the Dahomey military forces)

Residents-general (and their subordinate residents)

British resident (-general)

British Malay states and possessions

At the "national" level of British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. U ...

, after the post of High Commissioner had been filled (1 July 1896 – 1 April 1946) by the governors of the Straits Settlements (see Singapore), Britain appointed the following residents-general:

* 1 July 1896 – 1901 Frank Athelstane Swettenham

Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham (28 March 1850 – 11 June 1946) was a British colonial administrator who became the first Resident general of the Federated Malay States, which brought the Malay states of Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan an ...

(b. 1850 – d. 1946; from 1897, Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham)

* 1901–1904 William Hood Treacher

Sir William Hood Treacher (1 December 1849 – 3 May 1919) was a British colonial administrator in Borneo and the Straits Settlements. He founded the Anglo Chinese School in Klang on 10 March 1893.

Family

Treacher was the fourth son of Rev. ...

(b. 1849 – d. 1919)

* 1904–1910 Sir William Thomas Taylor (b. 1848 – d. 1931)

* 1910–1911 Arthur Henderson Young (b. 1854 – d. 1938)

Then there were various British chief secretaries 1911–1936 and two federal secretaries until 31 January 1942; after three Japanese military governors, the British Governor (1 April 1946 – 1 February 1948) stayed on as first of four High Commissioners as de facto governor-general of the Federation of Malaya until independence on 31 August 1957 saw the creation of an elective federal paramount ruler

{{Use American English, date=December 2018

The term paramount ruler, or sometimes paramount king, is a generic description, though occasionally also used as an actual title, for a number of rulers' position in relative terms, as the summit of a fe ...

styled Yang Dipertuan Agong (since 16 September 1961 with the addition ''bagi Malaysia'').

There were specific residents accredited in most constituent Malay states

The monarchies of Malaysia refer to the constitutional monarchy system as practised in Malaysia. The political system of Malaysia is based on the Westminster parliamentary system in combination with features of a federation.

Nine of the states ...

:

* 1885–1911 British Residents were appointed to the Sultans (until 1886 styled Maharaja) of Johore

Johor (; ), also spelled as Johore, is a state of Malaysia in the south of the Malay Peninsula. Johor has land borders with the Malaysian states of Pahang to the north and Malacca and Negeri Sembilan to the northwest. Johor shares maritime bor ...

, an unfederated state until 1946; thereafter the British crown was represented by General Advisers until the Japanese occupation, finally by Commissioners 1945–1948

* 1888–1941 to the Yang Di Pertuan Besar (state's elective ruler) of the nine member-confederation Negeri Sembilan

Negeri Sembilan (, Negeri Sembilan Malay: ''Nogoghi Sombilan'', ''Nismilan'') is a state in Malaysia which lies on the western coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It borders Selangor on the north, Pahang in the east, and Malacca and Johor to the s ...

, which accepted a British protectorate in 1888 and acceded in 1896 to the Federation; again British Commissioners after the Japanese occupation

** 1883–1895 additional British Residents were appointed to the Yang Di-Pertuan Muda (ruler) of Jelebu

The Jelebu District (Negeri Sembilan Malay: ''Jolobu'') is the second largest district in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia after Jempol, with a population over 40,000. Jelebu borders on the Seremban District to its west and Kuala Pilah District to ...

, a major member principality

** 1875–1889 additional British Residents were also appointed to the Undang Luak Sungai Ujong (ruler) of Sungai Ujong, another major member principality

* 1888–1938 British Residents were appointed to the Sultans (until 1882 styled Bendahara Seri Maharaja

Bendahara ( Jawi: بنداهارا) is an administrative position within classical Malay kingdoms comparable to a vizier before the intervention of European powers during the 19th century. A bendahara was appointed by a sultan and was a hered ...

) of Pahang

Pahang (;Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , Pahang Hulu Malay: ''Paha'', Pahang Hilir Malay: ''Pahaeng'', Ulu Tembeling Malay: ''Pahaq)'' officially Pahang Darul Makmur with the Arabic honorific ''Darul Makmur'' (Jawi: , "The Abode of Tranquility") is a ...

from the start of the British protectorate; again British Commissioners after the Japanese occupation

* 1874–1941 British Residents to the Sultans of Perak

Perak () is a state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kelantan and Pahang to the east, and Selangor to the south. Thailand's ...

as written in the Pangkor Treaty of 1874

The Pangkor Treaty of 1874 was a treaty signed between Great Britain and the Sultan of Perak on 20 January 1874, on the Colonial Steamer Pluto, off the coast of Perak. The treaty is significant in the history of the Malay states as it legitimis ...

, since they exchanged Thai sovereignty for a British protectorate; since 1 July 1896 part of the Federated Malay States; after the Japanese occupation a single British Commissioner

* 1875–1941 British Residents to the Sultans of Selangor

Selangor (; ), also known by its Arabic language, Arabic honorific Darul Ehsan, or "Abode of Sincerity", is one of the 13 Malaysian states. It is on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and is bordered by Perak to the north, Pahang to the east ...

during the Klang War

The Klang War or Selangor Civil War was a series of conflicts that lasted from 1867 to 1874 in the Malay state of Selangor in the Malay Peninsula (modern-day Malaysia).

It was initially fought between Raja Abdullah bin Raja Jaafar, the admini ...

, a year after accepting British protectorate (never under Thailand), 1 July 1896 part of Federated Malay States; after the Japanese occupation British Commissioners

A similar position, under another title, was held in the other Malay states:

* 1909–41 British Advisers replaced the Thai king's Advisers in the sultanate of Kedah

Kedah (), also known by its honorific Darul Aman (Islam), Aman and historically as Queda, is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia, located in the northwestern part of Peninsular Malaysia. The state covers a total area ...

, an unfederated state; after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed

* 1903–41 British Advisers replaced Thai ones in the sultanate of Kelantan

Kelantan (; Jawi: ; Kelantanese Malay: ''Klate'') is a state in Malaysia. The capital is Kota Bharu and royal seat is Kubang Kerian. The honorific name of the state is ''Darul Naim'' (Jawi: ; "The Blissful Abode").

Kelantan is located in the ...

, an unfederated state; after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed

* 1909–1941 British Advisers replaced Thai ones with the Rajas of Perlis

Perlis, ( Northern Malay: ''Peghelih''), also known by its honorific title Perlis Indera Kayangan, is the smallest state in Malaysia by area and population. Located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, it borders the Thai provinces o ...

, since the acceptance of British protectorate as an unfederated state instead of the Thai sovereignty (since the secession from Kedah) and were appointed again after Japanese and Thai occupation, until 1 April 1946 it joins the Malay Union (from 16 September 1963, Malaysia)

* 1904–25 British Agents were appointed to the Sultans of Terengganu

Terengganu (; Terengganu Malay: ''Tranung'', Jawi: ), formerly spelled Trengganu or Tringganu, is a sultanate and constitutive state of federal Malaysia. The state is also known by its Arabic honorific, ''Dāru l- Īmān'' ("Abode of Faith"). ...

, i.e. even before the 9 July 1909 exchange of Thai sovereignty for a British protectorate as unfederated Malay state, then Advisers 1919–1941 (overlap merely both titles for the same incumbent); after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed.

In the Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were a group of British territories located in Southeast Asia. Headquartered in Singapore for more than a century, it was originally established in 1826 as part of the territories controlled by the British East India Comp ...

, under direct British rule:

* in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, after two separate British Residents (7 February 1819 – December 1822 William Farquhar, then John Crawfurd), the Governors of the Straits Settlements filled the post 1826 – 15 February 1942; after four Japanese Military Administrators and two Japanese Mayors, a British Military Administrator 12 September 1945 – 1 April 1946, then four British Governors and the second incumbent stayed on as first of two gubernatorial 'Heads of state' styled yang di-pertuan negara

Yang di-Pertuan Negara (English: (he) who is Lord of the State) is a title for the head of state in certain Malay language, Malay-speaking countries, and has been used as an official title at various times in Brunei and Singapore.

Sabah

The head ...

, his Malay successor also becoming the first President after independence

* In Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

(Melaka), a former Dutch colony, seven consecutive British Residents were in office 1795–1818, followed by three Dutch governors; after the final inclusion in the British Strait Settlements, 1826, most were titled Resident Councillor, except the period 1910–1920 reverting to the style Resident; after the Japanese occupation, Resident Commissioner

Resident commissioner was or is an official title of several different types of commissioners, who were or are representatives of any level of government. Historically, they were appointed by the British Crown in overseas protectorates (such ...

s took their place until the 1957 independence installed Malaysian Governors and Chief Ministers

* In Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay ...

(Pinang), after three Superintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

s for the British East India Company (1786–1799; only Prince of Wales Island had yet been ceded to the British by the Sultan of Kedah), then two Lieutenant-governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

s (in 1801 Province Wellesley on the mainland was added) and many Governors after 1805 (since 1826 as part of the Strait Settlements), only Resident Councillors were in office 1849–1941 (name Penang assumed in 1867); after four Japanese and since 1945 two British military governors, four Resident Commissioners 1946–1957, since then Malaysian-appointed "heads of state".

On Northern Borneo, contrary to the Malay peninsula, no such officials were appointed, in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the M ...

and Sabah

Sabah () is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia located in northern Borneo, in the region of East Malaysia. Sabah borders the Malaysian state of Sarawak to the southwest and the North Kalimantan province of Indone ...

as there were white rulers or governors; but to the still sovereign Sultans of Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely sur ...

, lying between those larger states, British Residents were appointed 1906–1959 (interrupted by Japanese commander Masao Baba 6 January 1942 – 14 June 1945), afterwards only High Commissioners for the matters not transferred under autonomy (and 1971 self-government) until full independence went in force 1 January 1984. The administrative head of Sarawak's geographical Divisions was, however, titled as Resident.

French

The French word is ''Résident-général''.

Africa

* In Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, accredited with the Sultan: Residents-general 28 April 1912 – 2 March 1956 (first incumbent previously military governor)

* In Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, accredited with the Basha Bey

Basha may refer to:

*Baasha (king), a Hebrew king

* ''Basha'' (film), a Tamil movie

*Basha (tarpaulin), British military slang for a shelter or sleeping area

* Arabic pronunciation of the Turkish title "Pasha", formerly used by some Arab rulers in ...

Residents-general 23 June 1885 – 31 August 1955; first incumbent was the last of the two previous Resident ministers

* On Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

: 28 April 1886 – 31 July 1897

Indochina

* In present Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

& Laos: Residents-general for Annam-Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain ''Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includi ...

(at Hué) 11 June 1884 – 9 May 1889

** Residents-Superior for Annam (also at Hué) 1886–1950s (at least 1953)

** Residents-Superior for Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain ''Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includi ...

(at Hanoi; subordinated to Annam until 1888) 1886–1950s (at least 1953)—but none in Cochinchina

** Residents-superior for Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

September 1895 – 5 April 1945

* In Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

Residents-general 12 August 1885 – 16 May 1889;

** later downgraded (under Hué) to Residents-superior 16 May 1889 – 15 October 1945

** several regional Résidents

Belgian

(Belgium mainly used French in the colonies; the word in its other official language, Dutch, is ''Resident-generaal'')

* Ruanda-Urundi

Ruanda-Urundi (), later Rwanda-Burundi, was a colonial territory, once part of German East Africa, which was occupied by troops from the Belgian Congo during the East African campaign in World War I and was administered by Belgium under militar ...

(cfr. German above; there were Belgian Residents ): 1960 – 1 July 1962 Jean-Paul Harroy

Jean-Paul Harroy (4 May 1909 – 8 July 1995) was a Belgian colonial civil servant who served as the last Governor and only Resident-General of Ruanda-Urundi. His term coincided with the Rwandan Revolution and the assassination of the popular Bur ...

(b. 1909 – d. 1995), staying on after being its Belgian last Governor (and Deputy Governor-General of the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

)

Japanese (original title)

In the protectorate Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, accredited to the Choson Monarch (rendered as King or Emperor) 21 Dec 1905 – 1 Oct 1910 three incumbents (including Hirobumi Ito the former Prime Minister of Japan), all Japanese peers (new western-type styles, rendered as: Marquess/Duke or Viscount); the last stayed on as the first Governor-General after full annexation to Japan. See: List of Japanese Residents-General of Korea

The resident-general was the leader of Korea under Japanese rule from 1905 to 1910.

Itō Hirobumi was the first resident-general. There were three residents-general in total. After the annexation of Korea to Japan, the last resident-general, Ter ...

Postcolonial residents

On occasion, residents were maintained, notably by former colonial powers, in territories in a transitional process to a new constitutional status, such as full independence. Such function could also be performed under another title, such as Commissioner or High Commissioner.

Thus after World War I, there were residents in some mandate territories:

* after the French and British occupation of the former German colony Kamerun