Requiem (Verdi) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Messa da Requiem'' is a musical setting of the

However, on 4 November, nine days before the premiere, the organising committee abandoned it. Verdi blamed this on the scheduled conductor, Angelo Mariani. He pointed to Mariani's lack of enthusiasm for the project, even though he had been part of the organising committee from the start, and it marked the beginning of the end of their friendship. The composition remained unperformed until 1988, when

However, on 4 November, nine days before the premiere, the organising committee abandoned it. Verdi blamed this on the scheduled conductor, Angelo Mariani. He pointed to Mariani's lack of enthusiasm for the project, even though he had been part of the organising committee from the start, and it marked the beginning of the end of their friendship. The composition remained unperformed until 1988, when

The ''Requiem'' was first performed in the church of

The ''Requiem'' was first performed in the church of

*1.

*1.

Throughout the work, Verdi uses vigorous rhythms, sublime melodies, and dramatic contrasts—much as he did in his operas—to express the powerful emotions engendered by the text. The terrifying (and instantly recognizable) "Dies irae" that introduces the traditional

Throughout the work, Verdi uses vigorous rhythms, sublime melodies, and dramatic contrasts—much as he did in his operas—to express the powerful emotions engendered by the text. The terrifying (and instantly recognizable) "Dies irae" that introduces the traditional

Messa Da Requiem

published by

Live Recording of ''Liber Scriptus'' portion of ''Requiem'' (Mary Gayle Greene, mezzo-soprano)

* * {{Authority control Compositions by Giuseppe Verdi

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

funeral mass (Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

) for four soloists, double choir and orchestra by Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

. It was composed in memory of Alessandro Manzoni

Alessandro Francesco Tommaso Antonio Manzoni (, , ; 7 March 1785 – 22 May 1873) was an Italian poet, novelist and philosopher. He is famous for the novel '' The Betrothed'' (orig. it, I promessi sposi) (1827), generally ranked among the maste ...

, whom Verdi admired. The first performance, at the San Marco

San Marco is one of the six sestiere (Venice), sestieri of Venice, lying in the heart of the city as the main place of Venice. San Marco also includes the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. Although the district includes Piazza San Marco, Saint ...

church in Milan on 22 May 1874, marked the first anniversary of Manzoni's death. The work was at one time referred to as the Manzoni Requiem. Considered too operatic to be performed in a liturgical setting, it is usually given in concert form of around 90 minutes in length. Musicologist David Rosen calls it "probably the most frequently performed major choral work composed since the compilation of Mozart's Requiem

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version date ...

".

Composition history

AfterGioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's death in 1868, Verdi suggested that a number of Italian composers collaborate on a ''Requiem'' in Rossini's honor. He began the effort by submitting the concluding movement, the " Libera me". During the next year a '' Messa per Rossini'' was compiled by Verdi and twelve other famous Italian composers of the time. The premiere was scheduled for 13 November 1869, the first anniversary of Rossini's death.

Helmuth Rilling

Helmuth Rilling (born 29 May 1933) is a German choral conductor and an academic teacher. He is the founder of the Gächinger Kantorei (1954), the Bach-Collegium Stuttgart (1965), the Oregon Bach Festival (1970),

the Internationale Bachakademie S ...

premiered the complete ''Messa per Rossini'' in Stuttgart, Germany.

In the meantime, Verdi kept toying with his "Libera me", frustrated that the combined commemoration of Rossini's life would not be performed in his lifetime.

On 22 May 1873, the Italian writer and humanist Alessandro Manzoni

Alessandro Francesco Tommaso Antonio Manzoni (, , ; 7 March 1785 – 22 May 1873) was an Italian poet, novelist and philosopher. He is famous for the novel '' The Betrothed'' (orig. it, I promessi sposi) (1827), generally ranked among the maste ...

, whom Verdi had admired all his adult life and met in 1868, died. Upon hearing of his death, Verdi resolved to complete a Requiem—this time entirely of his own writing—for Manzoni. Verdi traveled to Paris in June, where he commenced work on the ''Requiem'', giving it the form we know today. It included a revised version of the "Libera me" originally composed for Rossini.

Performance history

19th century

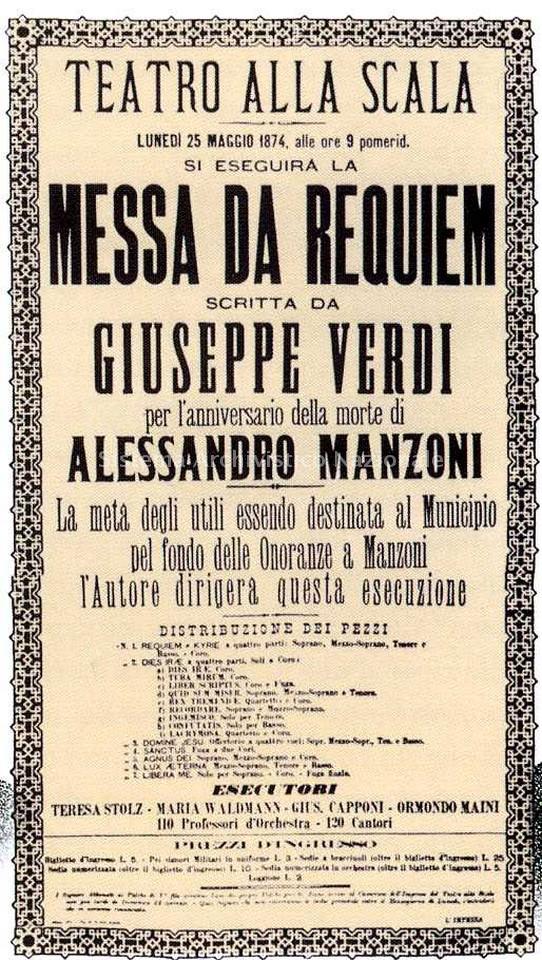

The ''Requiem'' was first performed in the church of

The ''Requiem'' was first performed in the church of San Marco

San Marco is one of the six sestiere (Venice), sestieri of Venice, lying in the heart of the city as the main place of Venice. San Marco also includes the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. Although the district includes Piazza San Marco, Saint ...

in Milan on 22 May 1874, the first anniversary of Manzoni's death. Verdi himself conducted, and the four soloists were Teresa Stolz

Teresa Stolz (born 2 June 1834, Elbekosteletz (Czech: Kostelec nad Labem), Bohemia – died 23 August 1902, Milan) was a Bohemian soprano, long resident in Italy, who was associated with significant premieres of the works of Giuseppe Verdi, an ...

(soprano), Maria Waldmann

Maria Waldmann (19 November 1845 – 6 November 1920) was an Austrian mezzo-soprano who had a noted association with Giuseppe Verdi.

She was born in Vienna in 1845 and studied with Francesco Lamperti. She dedicated herself to the Italian mez ...

(mezzo-soprano), Giuseppe Capponi (tenor) and (bass).

As Aida, Amneris and Ramfis respectively, Stolz, Waldmann, and Maini had all sung in the European premiere of ''Aida

''Aida'' (or ''Aïda'', ) is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Set in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, it was commissioned by Cairo's Khedivial Opera House and had its première there on 24 December ...

'' in 1872, and Capponi was also intended to sing the role of Radames at that premiere but was replaced due to illness. Teresa Stolz went on to a brilliant career, Waldmann retired very young in 1875, but the male singers appear to have faded into obscurity. Also, Teresa Stolz was engaged to Angelo Mariani in 1869, but she later left him.

The Requiem was repeated at La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

three days later on 25 May with the same soloists and Verdi again conducting. It won immediate contemporary success, although not everywhere. It received seven performances at the Opéra-Comique

The Opéra-Comique is a Paris opera company which was founded around 1714 by some of the popular theatres of the Parisian fairs. In 1762 the company was merged with – and for a time took the name of – its chief rival, the Comédie-Italienne ...

in Paris, but the new Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

in London could not be filled for such a Catholic occasion. In Venice, impressive Byzantine ecclesiastical decor was designed for the occasion of the performance.

It later disappeared from the standard choral repertoire, but made a reappearance in the 1930s and is now regularly performed and a staple of many choral societies.

20th century and beyond

The Requiem was reportedly performed approximately 16 times between 1943 and 1944 by prisoners in the concentration camp ofTheresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the Schutzstaffel, SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (German occupation of Czechoslovakia, German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstad ...

(also known as Terezín) under the direction of Rafael Schächter

Rafael Schächter (born 25 May 1905, died on the death march during the evacuation of Auschwitz in 1945), was a Czechoslovak composer, pianist and conductor of Jewish origin, organizer of cultural life in Terezín concentration camp.

Life

...

. The performances were presented under the auspices of the , a cultural organization in the Ghetto.

Since the 1990s, commemorations in the US and Europe have included memorial performances of the Requiem in honor of the Terezín performances. On the heels of previous performances held at the Terezín Memorial, Murry Sidlin performed the Requiem in Terezin in 2006 and rehearsed the choir in the same basement where the original inmates reportedly rehearsed. Part of the Prague Spring Festival, two children of survivors sang in the choir with their parents sitting in the audience.

The Requiem has been staged in a variety of ways several times in recent years. Achim Freyer

Achim Freyer (; born 30 March 1934) is a German stage director, set designer and painter. A protégé of Bertolt Brecht, Freyer has become one of the world's leading opera directors, working throughout Europe and, since 2002, in the United Stat ...

created a production for the Deutsche Oper Berlin

The Deutsche Oper Berlin is a German opera company located in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin. The resident building is the country's second largest opera house (after Munich's) and also home to the Berlin State Ballet.

Since 2004, the De ...

in 2006 that was revived in 2007, 2011 and 2013. In Freyer's staging, the four sung roles, "Der Weiße Engel" (The White Angel), "Der Tod-ist-die-Frau" (Death is the Woman), "Einsam" (Solitude), and "Der Beladene" (The Load Bearer) are complemented by choreographed allegorical characters.

In 2011, Oper Köln

The Cologne Opera (German: Oper der Stadt Köln or Oper Köln) refers both to the main opera house in Cologne, Germany and to its resident opera company. History of the company

From the mid 18th century, opera was performed in the city's court th ...

premiered a full staging by Clemens Bechtel where the four main characters were shown in different life and death situations: the Fukushima nuclear disaster

The was a nuclear accident in 2011 at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Ōkuma, Fukushima, Japan. The proximate cause of the disaster was the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which occurred on the afternoon of 11 March 2011 and ...

, a Turkish writer in prison, a young woman with bulimia

Bulimia nervosa, also known as simply bulimia, is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating followed by purging or fasting, and excessive concern with body shape and weight. The aim of this activity is to expel the body of calories eate ...

, and an aid worker in Africa.

In 2021, the New York Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

performed the Requiem for the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

.

Versions and arrangements

For a Paris performance, Verdi revised the "Liber scriptus" to allowMaria Waldmann

Maria Waldmann (19 November 1845 – 6 November 1920) was an Austrian mezzo-soprano who had a noted association with Giuseppe Verdi.

She was born in Vienna in 1845 and studied with Francesco Lamperti. She dedicated herself to the Italian mez ...

a further solo for future performances. Previously, the movement had been set for a choral fugue in a classical Baroque style. With its premiere at the Royal Albert Hall performance in May 1875, this revision became the definitive edition that has been most performed since, although the original version is included in critical editions of the work published by Bärenreiter

Bärenreiter (Bärenreiter-Verlag) is a German classical music publishing house based in Kassel. The firm was founded by Karl Vötterle (1903–1975) in Augsburg in 1923, and moved to Kassel in 1927, where it still has its headquarters; it also ...

and University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

.

Versions accompanied by four pianos or brass band were also performed.

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

transcribed the ''Agnus Dei'' for solo piano (S. 437). It has been recorded by Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director and producer.Obituary ''Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and '' Vanity Fair'' and was one ...

.

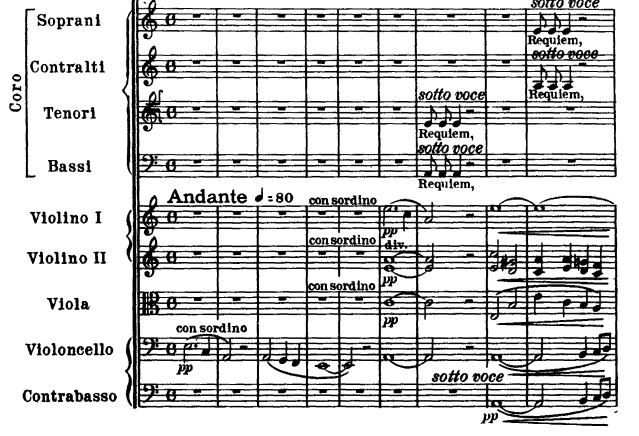

Sections

Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

**''Introit'' (chorus)

**''Kyrie'' (soloists, chorus)

*2. Dies irae

**''Dies irae'' (chorus)

**''Tuba mirum'' (chorus)

**''Mors stupebit'' (bass)

**''Liber scriptus'' (mezzo-soprano, chorus – chorus only in original version)

**''Quid sum miser'' (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor)

**''Rex tremendae'' (soloists, chorus)

**''Recordare'' (soprano, mezzo-soprano)

**''Ingemisco'' (tenor)

**''Confutatis maledictis'' (bass, chorus)

**''Lacrymosa'' (soloists, chorus)

*3. Offertory

The offertory (from Medieval Latin ''offertorium'' and Late Latin ''offerre'') is the part of a Eucharistic service when the bread and wine for use in the service are ceremonially placed on the altar.

A collection of alms (offerings) from the c ...

**''Domine Jesu Christe'' (soloists)

**''Hostias'' (soloists)

*4. Sanctus

The Sanctus ( la, Sanctus, "Holy") is a hymn in Christian liturgy. It may also be called the ''epinikios hymnos'' ( el, ἐπινίκιος ὕμνος, "Hymn of Victory") when referring to the Greek rendition.

In Western Christianity, the ...

(double chorus)

*5. Agnus Dei

is the Latin name under which the " Lamb of God" is honoured within the Catholic Mass and other Christian liturgies descending from the Latin liturgical tradition. It is the name given to a specific prayer that occurs in these liturgies, and ...

(soprano, mezzo-soprano, chorus)

*6. Lux aeterna (mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass)

*7. Libera me (soprano, chorus)

**''Libera me''

**''Dies irae''

**''Requiem aeternam''

**''Libera me''

Music

sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is calle ...

of the Latin funeral rite is repeated throughout. Trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s surround the stage to produce a call to judgement in the "Tuba mirum", and the almost oppressive atmosphere of the "Rex tremendae" creates a sense of unworthiness before the King of Tremendous Majesty. Yet the well-known tenor

A tenor is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The lo ...

solo "Ingemisco" radiates hope for the sinner who asks for the Lord's mercy.

The "Sanctus" (a complicated eight-part fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

scored for double chorus) begins with a brassy fanfare to announce him "who comes in the name of the Lord". Finally the "Libera me", the oldest music by Verdi in the ''Requiem'', interrupts. Here the soprano cries out, begging, "Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death ... when you will come to judge the world by fire."

When the Requiem was composed, female singers were not permitted to perform in Catholic Church rituals (such as a requiem mass). However, from the beginning Verdi intended to use female singers in the work. In his open letter proposing the ''Requiem'' project (when it was still conceived as a multi-author ''Requiem'' for Rossini), Verdi wrote: "If I were in the good graces of the Holy FatherPope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

I would beg him to permit—if only for this one time—that women take part in the performance of this music; but since I am not, it will fall to someone else better suited to obtain this decree." In the event, when Verdi composed the ''Requiem'' alone, two of the four soloists were sopranos, and the chorus included female voices. This may have slowed the work's acceptance in Italy.

At the time of its premiere, the ''Requiem'' was criticized by some as being too operatic in style for the religious subject matter. According to Gundula Kreuzer, "Most critics did perceive a schism between the religious text (with all its musical implications) and Verdi's setting." Some viewed it negatively as "an opera in ecclesiastical robes", or alternatively, as a religious work, but one in "dubious musical costume". While the majority of critics agreed that the music was "dramatic", some felt that such treatment of the text was appropriate, or at least permissible. As to the quality of the music, the critical consensus agreed that the work displayed "fluent invention, beautiful sound effects and charming vocal writing". Critics were divided between praise and condemnation with respect to Verdi's willingness to break standard compositional rules for musical effect, such as his use of consecutive fifths

In music, consecutive fifths or parallel fifths are progressions in which the interval of a perfect fifth is followed by a ''different'' perfect fifth between the same two musical parts (or voices): for example, from C to D in one part along ...

.

Instrumentation

The work is scored for the following orchestra: :woodwind

Woodwind instruments are a family of musical instruments within the greater category of wind instruments. Common examples include flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon, and saxophone. There are two main types of woodwind instruments: flutes and reed ...

: 3 flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

s (3rd doubling piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

), 2 oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

s, 2 clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches ...

s, 4 bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

s

:brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

: 4 horns Horns or The Horns may refer to:

* Plural of Horn (instrument), a group of musical instruments all with a horn-shaped bells

* The Horns (Colorado), a summit on Cheyenne Mountain

* ''Horns'' (novel), a dark fantasy novel written in 2010 by Joe Hill ...

, 8 trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s (4 offstage), 3 trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

s, ophicleide

The ophicleide ( ) is a family of conical-bore keyed brass instruments invented in early 19th century France to extend the keyed bugle into the alto, bass and contrabass ranges. Of these, the bass ophicleide in C or B took root over the cours ...

an obsolete instrument usually replaced by a tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

or cimbasso

The cimbasso is a low brass instrument that developed from the upright serpent over the course of the 19th century in Italian opera orchestras, to cover the same range as a tuba or contrabass trombone. The modern instrument has four to six rotary ...

in modern performances

:percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

: timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

, bass drum

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter much greater than the drum's depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. Th ...

:strings

String or strings may refer to:

*String (structure), a long flexible structure made from threads twisted together, which is used to tie, bind, or hang other objects

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Strings'' (1991 film), a Canadian anim ...

: violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

s I, II, viola

The viola ( , also , ) is a string instrument that is bow (music), bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of ...

s, violoncellos

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a bowed (sometimes plucked and occasionally hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifths: from low to high, C2, G2, D3 ...

, double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or #Terminology, by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched Bow (music), bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox addit ...

es.

Recordings

References

Notes Sources * * * * *Further reading

* Kennedy, Michael (2006), ''The Oxford Dictionary of Music''. *Verdi, Giuseppe; (Ed., Marco Uvietta, 2014) ''Messa da requiem''. Critical edition. Kassel:Bärenreiter

Bärenreiter (Bärenreiter-Verlag) is a German classical music publishing house based in Kassel. The firm was founded by Karl Vötterle (1903–1975) in Augsburg in 1923, and moved to Kassel in 1927, where it still has its headquarters; it also ...

.

External links

*Digitised copy of Verdi'Messa Da Requiem

published by

Ricordi

Ricordi may refer to:

People

*Giovanni Ricordi (1785–1853), Italian violinist and publishing company founder

* Giulio Ricordi (1840–1912), Italian publisher and musician

Music

*Casa Ricordi, an Italian music publishing company established i ...

in Milan 1874, from National Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS) ( gd, Leabharlann Nàiseanta na h-Alba, sco, Naitional Leebrar o Scotland) is the legal deposit library of Scotland and is one of the country's National Collections. As one of the largest libraries in the ...

.Live Recording of ''Liber Scriptus'' portion of ''Requiem'' (Mary Gayle Greene, mezzo-soprano)

* * {{Authority control Compositions by Giuseppe Verdi

Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

1874 compositions