Republican Spain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of

In June 1931 a

In June 1931 a

Arguing Comparative Politics

, p. 221, Oxford University Press

The majority vote in the 1933 elections was won by the

The majority vote in the 1933 elections was won by the

On 7 January 1936, new elections were called. Despite significant rivalries and disagreements, the socialists, Communists, and the Catalan-and-Madrid-based left-wing Republicans decided to work together under the name

On 7 January 1936, new elections were called. Despite significant rivalries and disagreements, the socialists, Communists, and the Catalan-and-Madrid-based left-wing Republicans decided to work together under the name

In response a group of

In response a group of  The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right. Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.

The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right. Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.

On 17 July 1936, General Franco led the

On 17 July 1936, General Franco led the

Simpson, James

/ref>

Constitución de la República Española (1931)

English Translation of the Constitution of the Spanish Republic (1931)

* *

Video La II República Española

{{Authority control States and territories established in 1931 States and territories disestablished in 1939 Modern history of Spain Spanish Republic, Second Political history of Spain Republicanism in Spain 1931 establishments in Spain 1939 disestablishments in Spain Former countries of the interwar period

King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alf ...

, and was dissolved on 1 April 1939 after surrendering in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

to the Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

led by General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

.

After the proclamation of the Republic, a provisional government was established until December 1931, at which time the 1931 Constitution was approved. During this time and the subsequent two years of constitutional government, known as the Reformist Biennium, Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

's executive initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would modernize the country. In 1932 the Jesuits, who were in charge of the best schools throughout the country, were banned and had all their property confiscated in favour of government-supervised schools, while the government began a large scale school-building projects. A moderate agrarian reform was carried out. Home rule was granted to Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, with a local parliament and a president of its own.

Soon, Azaña lost parliamentary support and President Alcalá-Zamora forced his resignation in September 1933. The subsequent 1933 election was won by the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in t ...

(CEDA). However the President declined to invite its leader, Gil Robles, to form a government, fearing CEDA's monarchist sympathies. Instead, he invited the Radical Republican Party

The Radical Republican Party ( es, Partido Republicano Radical), sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a ...

's Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

to do so. CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year. In October 1934, CEDA was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. The Socialists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months. A general strike was called by the UGT and the PSOE in the name of the ''Alianza Obrera''.Payne, Stanley G. The collapse of the Spanish republic, 1933–1936: Origins of the civil war. Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 84–85 The rebellion developed into a bloody revolutionary uprising, aiming to overthrow the republican government. Armed revolutionaries managed to take the whole province of Asturias, committing numerous murders of policemen, clerics and civilians and destroying religious buildings and part of the University of Oviedo

The University of Oviedo ( es, Universidad de Oviedo, Asturian: ''Universidá d'Uviéu'') is a public university in Asturias (Spain). It is the only university in the region. It has three campus and research centres, located in Oviedo, Gijón ...

. In the occupied areas, the rebels officially declared a proletarian revolution and abolished regular money. The rebellion was crushed by the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

and the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Repú ...

, the latter using mainly Moorish colonial troops from Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

.

In 1935, after a series of crisis and corruption scandals, President Alcalá-Zamora, who had always been hostile to the government, called for new elections, instead of inviting CEDA, the party with most seats in the parliament, to form a new government. The Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

won the 1936 general election with a narrow victory. The revolutionary left wing masses took to the streets, released prisoners. Within hours, sixteen people were killed, and thirty-nine were seriously injured. Meanwhile, fifty churches and seventy right wing political centres were attacked.Alvarez Tardio, Manuel. "Mobilization and political violence following the Spanish general elections of 1936". REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS POLITICOS 177 (2017): 147–179. Manuel Azaña Díaz

Manuel may refer to:

People

* Manuel (name)

* Manuel (Fawlty Towers), a fictional character from the sitcom ''Fawlty Towers''

* Charlie Manuel, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies

* Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine Empire

* Manu ...

was called upon to form a government before the electoral process had come to an end; he would shortly replace Zamora as president, taking advantage of a constitutional loophole. The Right abandoned the parliamentary option and began to conspire to overthrow the Republic, rather than taking control of it.

The disenchantment with Azaña's ruling was voiced by Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay w ...

, a republican and one of Spain's most respected intellectuals, who said that President Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

should commit suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

as a patriotic act. On 12 July 1936, a group of Guardia de Asalto

The Cuerpo de Seguridad y Asalto ( en, Security and Assault Corps) was the heavy reserve force of the blue-uniformed urban police force of Spain during the Spanish Second Republic. The Assault Guards were special police and paramilitary units cr ...

and other leftist militiamen went to opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician, minister of Finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Second Republic. During t ...

's house and mortally shot him. This assassination had an electrifying effect which provided a catalyst to transform what was a "limping conspiracy", led by General Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, M ...

, into a powerful revolt. Three days later (17 July), the revolt began with an army uprising in Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

. The revolt then spread to several regions of the country. Military rebels intended to seize power immediately, but they were met with serious resistance as most of the main cities remained loyal to the Republic. An estimated total of half a million people would lose their lives in the war that followed.

During the Spanish Civil War, there were three governments. The first was led by left-wing republican José Giral

José Giral y Pereira (22 October 1879 – 23 December 1962) was a Spanish politician, who served as the 75th Prime Minister of Spain during the Second Spanish Republic.

Life

Giral was born in Santiago de Cuba. He had degrees in Chemistry a ...

(from July to September 1936); however, a revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

inspired mostly by libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

, anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

and communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

principles broke within the Republic, which weakened the rule of the Republic. The second government was led by socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

Francisco Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

of the trade union General Union of Workers

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED On ...

(UGT). The UGT, along with the National Confederation of Workers (CNT), were the main forces behind the aforementioned social revolution. The third government was led by socialist Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and served as finance minister and ...

, who led the Republic until the military coup of Segismundo Casado

Segismundo Casado López (10 October 1893 – 18 December 1968) was a Spanish Army officer; he served during the late Restoration, the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the Second Spanish Republic. Following outbreak of the Spanish Civil War ...

, which ended republican resistance and ultimately led to the victory of the nationalists.

The Republican government survived in exile and retained an embassy in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

until 1976. After the restoration of democracy in Spain, the government-in-exile formally dissolved the following year.

1931–1933 The Reformist Biennium

On 28 January 1930, the military dictatorship of GeneralMiguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

(who had been in power since September 1923) was overthrown. This led various republican factions from a wide variety of backgrounds (including conservatives, socialists and Catalan nationalists) to join forces. The Pact of San Sebastián The Pact of San Sebastián was a meeting led by Niceto Alcalá Zamora and Miguel Maura, which took place in San Sebastián, Spain on 17 August 1930. Representatives from practically all republican political movements in Spain at the time attended t ...

was the key to the transition from monarchy to republic. Republicans of all tendencies were committed to the Pact of San Sebastian in overthrowing the monarchy and establishing a republic. The restoration of the royal Bourbons was rejected by large sectors of the populace who vehemently opposed the King. The pact, signed by representatives of the main Republican forces, allowed a joint anti-monarchy political campaign. The 12 April 1931 municipal elections led to a landslide victory for republicans. Two days later, the Second Republic was proclaimed, and King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alfo ...

went into exile. The king's departure led to a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

of the young republic under Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

. Catholic churches and establishments in cities like Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and Sevilla

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Gua ...

were set ablaze on 11 May.

1931 Constitution

In June 1931 a

In June 1931 a Constituent Cortes

The Constituent Cortes ( es, Las Cortes Constituyentes) is the description of Spain's parliament, the Cortes, when convened as a constituent assembly.

In the 20th century, only one Constituent Cortes was officially opened (Cortes are "opened" in ...

was elected to draft a new constitution, which came into force in December.

The new constitution established freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

and freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline membe ...

, extended suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

to women in 1933, allowed divorce, and stripped the Spanish nobility of any special legal status. It also effectively disestablished the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, but the disestablishment was somewhat reversed by the Cortes that same year. Its controversial articles 26 and 27 imposed stringent controls on Church property and barred religious orders from the ranks of educators. Scholars have described the constitution as hostile to religion, with one scholar characterising it as one of the most hostile of the 20th century.Stepan, AlfredArguing Comparative Politics

, p. 221, Oxford University Press

José Ortega y Gasset

José Ortega y Gasset (; 9 May 1883 – 18 October 1955) was a Spanish philosopher and essayist. He worked during the first half of the 20th century, while Spain oscillated between monarchy, republicanism, and dictatorship. His philosoph ...

stated, "the article in which the Constitution legislates the actions of the Church seems highly improper to me." Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

condemned the Spanish government's deprivation of the civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

of Catholics in the encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally from ...

''Dilectissima Nobis

''Dilectissima Nobis'' ("On Oppression of the Church of Spain") is an encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI on June 3, 1933, in which he decried persecution of the Church in Spain, citing the expropriation of all Church buildings, episcopal residenc ...

''.

The legislative branch was changed to a single chamber called the Congress of Deputies

The Congress of Deputies ( es, link=no, Congreso de los Diputados, italic=unset) is the lower house of the Cortes Generales, Spain's legislative branch. The Congress meets in the Palacio de las Cortes, Madrid, Palace of the Parliament () in Ma ...

. The constitution established legal procedures for the nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of public services and land, banks, and railways. The constitution provided generally accorded civil liberties and representation.

The Republican Constitution also changed the country's national symbols. The ''Himno de Riego

The "Himno de Riego" ("Anthem of Riego") is a song dating from the ''Trienio Liberal'' (1820–1823) of Spain and named in honour of Colonel Rafael del Riego, a figure in the respective uprising, which restored the liberal Spanish Constitution o ...

'' was established as the national anthem, and the Tricolor, with three horizontal red-yellow-purple fields, became the new flag of Spain. Under the new Constitution, all of Spain's regions had the right to autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

. Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

(1932), the Basque Country (1936) and Galicia (although the Galician Statute of Autonomy couldn't come into effect due to the war) exercised this right, with Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, Andalusia and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

, engaged in negotiations with the government before the outbreak of the Civil War. The Constitution guaranteed a wide range of civil liberties, but it opposed key beliefs of the right wing, which was very rooted in rural areas, and desires of the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, which was stripped of schools and public subsidies.

The 1931 Constitution was formally effective from 1931 until 1939. In the summer of 1936, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, it became largely irrelevant after the authority of the Republic was superseded in many places by revolutionary socialists and anarchists on one side, and Nationalists on the other.

The Azaña government

With the new constitution approved in December 1931, once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned. However fearing the increasing popular opposition the Radicals and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, therefore prolonging their way in power for two more years. This way the republican government ofManuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would "modernize" the country.

In 1932 the Jesuits who were in charge of the best schools throughout the country were banned and had all their property confiscated. Landowners were expropriated. Autonomy was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of said parliament. Catholic churches in major cities were again subject to arson in 1932, and a revolutionary strike action was seen in Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

the same year. A Catholic church in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

was burnt down in 1933.

In November 1932, Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay w ...

, one of the most respected Spanish intellectuals, rector of the University of Salamanca, and himself a Republican, publicly raised his voice to protest. In a speech delivered on 27 November 1932, at the Madrid Ateneo, he protested: "Even the Inquisition was limited by certain legal guarantees. But now we have something worse: a police force which is grounded only on a general sense of panic and on the invention of non-existent dangers to cover up this over-stepping of the law."

In 1933, all remaining religious congregations were obliged to pay taxes and banned from industry, trade and educational activities. This ban was forced with strict police severity and widespread mob violence.

1933–1935 period and miners' uprising

The majority vote in the 1933 elections was won by the

The majority vote in the 1933 elections was won by the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in t ...

(CEDA). In face of CEDA's electoral victory, president Alcalá-Zamora declined to invite its leader, Gil Robles, to form a government. Instead he invited the Radical Republican Party

The Radical Republican Party ( es, Partido Republicano Radical), sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a ...

's Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

to do so. Despite receiving the most votes, CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year. After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, the largest party in the congress, was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. However the entrance of CEDA in the government, although being normal in a parliamentary democracy, was not well accepted by the left. The Socialists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months. A general strike was called by the UGT and the PSOE in the name of the ''Alianza Obrera''. The issue was that the Left Republicans identified the Republic not with democracy or constitutional law but with a specific set of left-wing policies and politicians. Any deviation, even if democratic, was seen as treasonous.

The inclusion of three CEDA ministers in the government that took office on 1 October 1934 led to a country wide revolt. A " Catalan State" was proclaimed by Catalan nationalist leader Lluis Companys

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archaic ...

, but it lasted just ten hours. Despite an attempt at a general stoppage in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, other strikes did not endure. This left Asturian strikers to fight alone. Miners in Asturias occupied the capital, Oviedo

Oviedo (; ast, Uviéu ) is the capital city of the Principality of Asturias in northern Spain and the administrative and commercial centre of the region. It is also the name of the municipality that contains the city. Oviedo is located ap ...

, killing officials and clergymen. Fifty eight religious buildings including churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo were burned and destroyed. The miners proceeded to occupy several other towns, most notably the large industrial centre of La Felguera

La Felguera is a parish of Langreo, and the most important district in the municipality of Langreo (Principality of Asturias) in northern Spain, with 21.000 inhabitants. It is located 18 minutes by car to Oviedo, the capital of Asturias. La Felg ...

, and set up town assemblies, or "revolutionary committees", to govern the towns that they controlled. Thirty thousand workers were mobilized for battle within ten days. In the occupied areas the rebels officially declared the proletarian revolution and abolished regular money. The revolutionary soviets set up by the miners attempted to impose order on the areas under their control, and the moderate socialist leadership of Ramón González Peña

Ramón González Peña (1888 – 27 July 1952) was an Asturian people, Asturian socialist and trade union leader. González was a prominent leader in the Asturian miners' strike of 1934, 1934 miners revolt in Asturias, under which he led the Ovie ...

and Belarmino Tomás

Belarmino Tomás Álvarez (29 April 1892 – 14 September 1950) was a socialist politician.

A secretary of the ''Sindicato Minero Asturiano'' (the local coal miners' branch of the Unión General de Trabajadores, UGT), and a delegate to the In ...

took measures to restrain violence. However, a number of captured priests, businessmen and civil guards were summarily executed by the revolutionaries in Mieres

Mieres is a municipality of Asturias, northern Spain, with approximately 38,000 inhabitants. The municipality of Mieres is made up of the capital, Mieres del Camino and the villages of Baiña, Figaredo, Cenera, Loredo, La Peña, La Rebollada, S ...

and Sama. This rebellion lasted for two weeks until it was crushed by the army, led by General Eduardo López Ochoa

Eduardo López Ochoa y Portoundo (1877 – 19 August 1936) was a Spanish general, Africanist, and prominent Freemason. He was known for most of his life as a traditional Republican, and conspired against the government of Miguel Primo de Rivera ...

. This operation earned López Ochoa the nickname "Butcher of Asturias". Another rebellion by the autonomous government of Catalonia, led by its president Lluís Companys

Lluís Companys i Jover (; 21 June 1882 – 15 October 1940) was a Catalan politician who served as president of Catalonia from 1934 and during the Spanish Civil War.

Companys was a lawyer close to labour movement and one of the most prominent l ...

, was also suppressed and was followed by mass arrests and trials.

With this rebellion against an established political legitimate authority, the Socialists showed identical repudiation of representative institutional system that anarchists had practiced. The Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga

Salvador de Madariaga y Rojo (23 July 1886 – 14 December 1978) was a Spanish diplomat, writer, historian, and pacifist. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the Charlemagne Prize in 197 ...

, an Azaña's supporter, and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco is the author of a sharp critical reflection against the participation of the left in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."

The suspension of the land reforms that had been attempted by the previous government, and the failure of the Asturias miners' uprising, led to a more radical turn by the parties of the left, especially in the PSOE (Socialist Party), where the moderate Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

lost ground to Francisco Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

, who advocated a socialist revolution. At the same time, the involvement of the Centrist government party in the Straperlo

Straperlo was a scheme which originated in the Netherlands in the 1930s and was then introduced in Spain. In essence it was a fraudulent roulette which could be controlled electrically with the push of a button. The ensuing scandal was one of the ...

scandal deeply weakened it, further polarising political differences between right and left. These differences became evident in the 1936 elections.

1936 elections

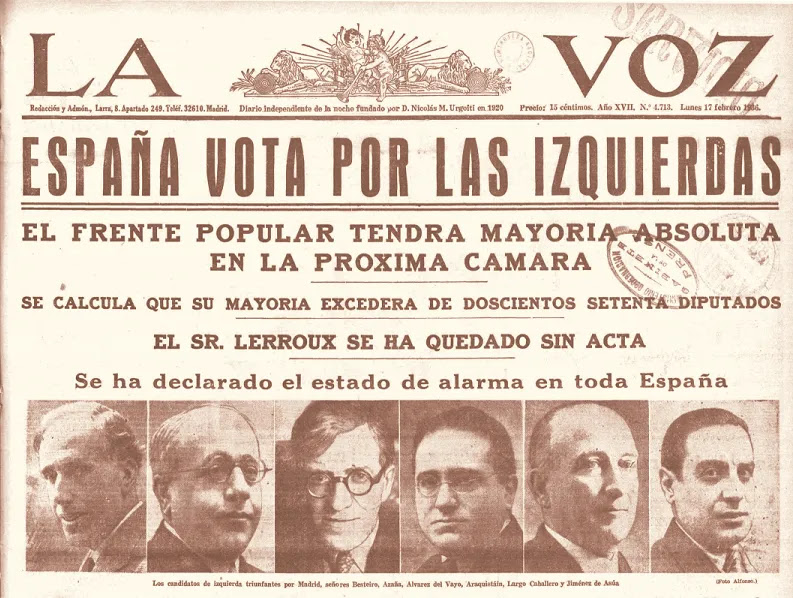

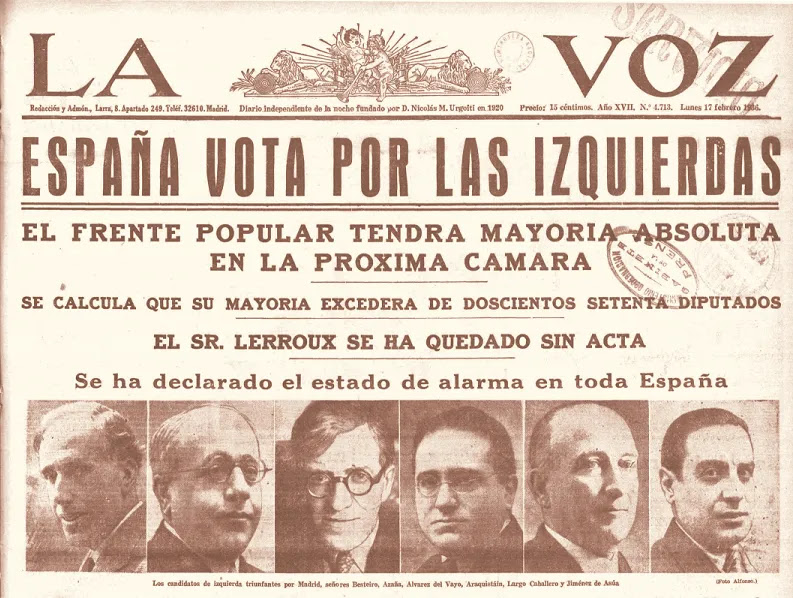

On 7 January 1936, new elections were called. Despite significant rivalries and disagreements, the socialists, Communists, and the Catalan-and-Madrid-based left-wing Republicans decided to work together under the name

On 7 January 1936, new elections were called. Despite significant rivalries and disagreements, the socialists, Communists, and the Catalan-and-Madrid-based left-wing Republicans decided to work together under the name Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

. The Popular Front won the election on 16 February with 263 MPs against 156 right-wing MPs, grouped within a coalition of the ''National Front'' with CEDA, Carlists

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

, and Monarchists. The moderate centre parties virtually disappeared; between the elections, Lerroux's group fell from the 104 representatives it had in 1934 to just 9.

American historian Stanley G. Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

thinks that there was major electoral fraud in the process, with widespread violation of the laws and the constitution. In line with Payne's point of view, in 2017 two Spanish Scholars, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García published the result of a research where they concluded that the 1936 elections were rigged. This view has been criticised by Eduardo Calleja and Francisco Pérez, who question the charges of electoral irregularity and argue that the Popular Front would still have won a slight electoral majority even if all of the charges were true.

In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured, while fifty churches and seventy right wing political centres were attacked or set ablaze. The right had firmly believed, at all levels, that they would win. Almost immediately after the results were known, a group of monarchists asked Robles to lead a coup but he refused. He did, however, ask prime minister Manuel Portela Valladares

Manuel Portela y Valladares (Pontevedra, 31 January 1867 – Bandol, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France 29 April 1952) was a Spanish political figure during the Second Spanish Republic. He served as the 43rd Attorney General of Spain betw ...

to declare a state of war before the revolutionary masses rushed into the streets. Franco also approached Valladares to propose the declaration of martial law and calling out of the army. This was not a coup attempt but more of a "police action" akin to Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

, as Franco believed the post-election environment could become violent and was trying to quell the perceived leftist threat.Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Hachette UK, 2012. Valladares resigned, even before a new government could be formed. However, the Popular Front, which had proved an effective election tool, did not translate into a Popular Front government. Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

and other elements of the political left were not prepared to work with the republicans, although they did agree to support much of the proposed reforms. Manuel Azaña Díaz

Manuel may refer to:

People

* Manuel (name)

* Manuel (Fawlty Towers), a fictional character from the sitcom ''Fawlty Towers''

* Charlie Manuel, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies

* Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine Empire

* Manu ...

was called upon to form a government before the electoral process had come to an end, and he would shortly replace Zamora as president, taking advantage of a constitutional loophole: the Constitution allowed the Cortes to remove the President from office after two early dissolutions, and while the first (1933) dissolution had been partially justified because of the fulfillment of the Constitutional mission of the first legislature, the second one had been a simple bid to trigger early elections.

The right reacted as if radical communists had taken control, despite the new cabinet's moderate composition; they were shocked by the revolutionary masses taking to the streets and the release of prisoners. Convinced that the left was no longer willing to follow the rule of law and that its vision of Spain was under threat, the right abandoned the parliamentary option and began to conspire as to how to best overthrow the republic, rather than taking control of it.

This helped the development of the fascist-inspired Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

Española, a National party led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella (24 April 1903 – 20 November 1936), often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish politician who founded the falangist Falange ...

, the son of the former dictator, Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

. Although it only received 0.7 percent of the votes in the election, by July 1936 the Falange had 40,000 members.

The country rapidly descended into anarchy. Even the socialist Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

at a party rally in Cuenca, in May 1936, complained: "we have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty."

In June 1936 Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay w ...

, disenchanted with the unfolding of the events told a reporter who published his statement in ''El Adelanto'' that President Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

should commit suicide as a patriotic act.

Assassinations of political leaders and beginning of the war

On 12 July 1936, Lieutenant José Castillo, an important member of the anti-fascist military organisationUnión Militar Republicana Antifascista

The Republican Antifascist Military Union ( es, Unión Militar Republicana Antifascista; UMRA) was a self-described anti-fascist organization for members of the Spanish Republican Armed Forces in Spain during the period of the Second Spanish Repub ...

(UMRA), was shot by Falangist

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the Fal ...

gunmen.

Guardia de Asalto

The Cuerpo de Seguridad y Asalto ( en, Security and Assault Corps) was the heavy reserve force of the blue-uniformed urban police force of Spain during the Spanish Second Republic. The Assault Guards were special police and paramilitary units cr ...

and other leftist militiamen led by Civil Guard

Civil Guard refers to various policing organisations:

Current

* Civil Guard (Spain), Spanish gendarmerie

* Civil Guard (Israel), Israeli volunteer police reserve

* Civil Guard (Brazil), Municipal law enforcement corporations in Brazil

Histori ...

Fernando Condés, after getting the approval of the minister of interior to illegally arrest a list of members of parliament, went to right-wing opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician, minister of Finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Second Republic. During t ...

's house in the early hours of 13 July on a revenge mission. Sotelo was arrested and later shot dead in a police truck. His body was dropped at the entrance of one of the city's cemeteries. According to all later investigations, the perpetrator of the murder was a socialist gunman, Luis Cuenca, who was known as the bodyguard of PSOE

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

leader Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

. Calvo Sotelo was one of the most prominent Spanish monarchists who, describing the government's actions as Bolshevist

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and anarchist, had been exhorting the army to intervene, declaring that Spanish soldiers would save the country from communism if "there are no politicians capable of doing so".

Prominent rightists blamed the government for Calvo Sotelo's assassination. They claimed that the authorities did not properly investigate it and promoted those involved in the murder whilst censoring those who cried out about it and shutting down the headquarters of right-wing parties and arresting right-wing party members, often on "flimsy charges". The event is often considered the catalyst for the further political polarisation that ensued, the Falange and other right-wing individuals, including Juan de la Cierva

Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu, 1st Count of la Cierva (; 21 September 1895 in Murcia, Spain – 9 December 1936 in Croydon, United Kingdom) was a Spanish civil engineer, pilot and a self taught aeronautical engineer. His most famous accomplish ...

, had already been conspiring to launch a military coup d'état against the government, to be led by senior army officers.

When the antifascist Castillo and the anti-socialist Calvo Sotelo were buried on the same day in the same Madrid cemetery, fighting between the Police Assault Guard and fascist militias broke out in the surrounding streets, resulting in four more deaths.

The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right. Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.

The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right. Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup. Stanley Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

claims that before these events, the idea of rebellion by army officers against the government had weakened; Mola had estimated that only 12% of officers reliably supported the coup and at one point considered fleeing the country for fear he was already compromised, and had to be convinced to remain by his co-conspirators. However, the kidnapping and murder of Sotelo transformed the "limping conspiracy" into a revolt that could trigger a civil war. The involvement of forces of public order and a lack of action against the attackers hurt public opinion of the government. No effective action was taken; Payne points to a possible veto by socialists within the government who shielded the killers who had been drawn from their ranks. The murder of a parliamentary leader by state police was unprecedented, and the belief that the state had ceased to be neutral and effective in its duties encouraged important sectors of the right to join the rebellion. Within hours of learning of the murder and the reaction, Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

, who until then had not been involved in the conspiracies, changed his mind on rebellion and dispatched a message to Mola to display his firm commitment.

Three days later (17 July), the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

began more or less as it had been planned, with an army uprising in Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, which then spread to several regions of the country.

The revolt was remarkably devoid of any particular ideology. The major goal was to put an end to anarchical disorder. Mola's plan for the new regime was envisioned as a "republican dictatorship", modelled after Salazar's Portugal and as a semi-pluralist authoritarian regime rather than a totalitarian fascist dictatorship. The initial government would be an all-military "Directory", which would create a "strong and disciplined state." General Sanjurjo would be the head of this new regime, due to being widely liked and respected within the military, though his position would be a largely symbolic due to his lack of political talent. The 1931 Constitution would be suspended, replaced by a new "constituent parliament" which would be chosen by a new politically purged electorate, who would vote on the issue of republic versus monarchy. Certain liberal elements would remain, such as separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion. Agrarian issues would be solved by regional commissioners on the basis of smallholdings but collective cultivation would be permitted in some circumstances. Legislation prior to February 1936 would be respected. Violence would be required to destroy opposition to the coup, though it seems Mola did not envision the mass atrocities and repression that would ultimately manifest during the civil war. Of particular importance to Mola was ensuring the revolt was at its core an Army affair, one that would not be subject to special interests and that the coup would make the armed forces the basis for the new state. However, the separation of church and state was forgotten once the conflict assumed the dimension of a war of religion, and military authorities increasingly deferred to the Church and to the expression of Catholic sentiment. However, Mola's program was vague and only a rough sketch, and there were disagreements among coupists about their vision for Spain.

Franco's move was intended to seize power immediately, but his army uprising met with serious resistance, and great swathes of Spain, including most of the main cities, remained loyal to the Republic of Spain. The leaders of the coup (Franco was not commander-in-chief yet) did not lose heart with the stalemate and apparent failure of the coup. Instead, they initiated a slow and determined war of attrition against the Republican government in Madrid.

As a result, an estimated total of half a million people would lose their lives in the war that followed; the number of casualties is actually disputed as some have suggested as many as a million people died. Over the years, historians kept lowering the death figures and modern research concluded that 500,000 deaths were the correct figure.

Civil war

Spanish Army of Africa

The Army of Africa ( es, Ejército de África, ar, الجيش الإسباني في أفريقيا, Al-Jaysh al-Isbānī fī Afriqā) or Moroccan Army Corps ( es, Cuerpo de Ejército Marroquí') was a field army of the Spanish Army that garriso ...

from Morocco to attack the mainland, while another force from the north under General Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, M ...

moved south from Navarre. Military units were also mobilised elsewhere to take over government institutions. Before long the professional Army of Africa had much of the south and west under the control of the rebels. Bloody purges followed in each piece of captured "Nationalist" territory in order to consolidate Franco's future regime.

Although both sides received foreign military aid, the help that Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

(as part of German involvement in the Spanish Civil War

German involvement in the Spanish Civil War commenced with the outbreak of war in July 1936, with Adolf Hitler immediately sending in powerful air and armored units to assist General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces. The Soviet Un ...

), and neighbouring Portugal gave the rebels was much greater and more effective than the assistance that the Republicans received from the USSR, Mexico, and volunteers of the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

. While the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

wholeheartedly assisted General Franco's military campaign, the governments of France, Britain, and other European powers looked the other way and let the Republican forces die, as the actions of the Non-Intervention Committee

During the Spanish Civil War, several countries followed a principle of non-intervention to avoid any potential escalation or possible expansion of the war to other states. That would result in the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in Au ...

would show. Imposed in the name of neutrality, the international isolation

International isolation is a penalty applied by the international community or a sizeable or powerful group of countries, like the United Nations, towards one nation, government or group of people. The same term may also refer to the state a coun ...

of the Spanish Republic ended up favouring the interests of the future Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.

The Siege of the Alcázar

The Siege of the Alcázar was a highly symbolic Nationalist victory in Toledo in the opening stages of the Spanish Civil War. The Alcázar of Toledo was held by a variety of military forces in favour of the Nationalist uprising. Militias of th ...

at Toledo early in the war was a turning point, with the rebels winning after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid, despite a Nationalist assault in November 1936, and frustrated subsequent offensives against the capital at Jarama

Jarama () is a river in central Spain. It flows north to south, and passes east of Madrid where the El Atazar Dam is built on a tributary, the Lozoya River. It flows into the river Tagus in Aranjuez. The Manzanares is a tributary of the Jarama ...

and Guadalajara in 1937. Soon, though, the rebels began to erode their territory, starving Madrid and making inroads into the east. The north, including the Basque country, fell in late 1937, and the Aragon front collapsed shortly afterward. The bombing of Guernica

On 26 April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (''Gernika'' in Basque) was aerial bombed during the Spanish Civil War. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist faction by its allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe's ...

was probably the most infamous event of the war and inspired Picasso's painting. It was used as a testing ground for the German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

. The Battle of the Ebro

The Battle of the Ebro ( es, Batalla del Ebro, ca, Batalla de l'Ebre) was the longest and largest battle of the Spanish Civil War and the greatest, in terms of manpower, logistics and material ever fought on Spanish soil. It took place between Ju ...

in July–November 1938 was the final desperate attempt by the Republicans to turn the tide. When this failed and Barcelona fell to the rebels in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican fronts collapsed, and Madrid fell in March 1939.

Economy

The Second Spanish Republic's economy was mostly agrarian, and many historians call Spain during this time a "backward nation". Major industries of the Second Spanish Republic were located in the Basque region (due to it having Europe's best high-grade non-phosphoric ore) and Catalonia. This greatly contributed to Spain's economic hardships, as their center of industry was located on the opposite side of the country from their resource reserves, resulting in immense transportation costs due to the mountainous Spanish terrain. Compounding economic woes was Spain's low export rate and heavily domestic manufacturing industry. High levels of poverty left many Spaniards open to extremist political parties in search of a solution./ref>

See also

*Spanish Republican Armed Forces

The Spanish Republican Armed Forces ( es, Fuerzas Armadas de la República Española) were initially formed by the following two branches of the military of the Second Spanish Republic:

*Spanish Republican Army (''Ejército de la República Espa ...

* Spanish Republican government in exile

* Flag of the Second Spanish Republic

The flag of the Second Spanish Republic, known in Spanish as ', was the official flag of Spain between 1931 and 1939 and the flag of the Spanish Republican government in exile until 1977. Its present-day use in Spain is associated with the moder ...

* Coat of Arms of the Second Spanish Republic

* Order of the Spanish Republic

The Order of the Spanish Republic (Spanish: "Orden de la República Española") was founded in 1932 in the Second Spanish Republic for civil and military merit to the state. It replaced the orders of merit of the former Spanish Monarchy and had ...

* LAPE

LAPE, Spanish Postal Airlines ''(Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas)'', was Spain's national airline during the Second Spanish Republic.

History

LAPE, often also spelt L.A.P.E. and colloquially known as ''"Las LAPE"'', replaced CLASSA (''Compa ...

(Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas), the Spanish Republican Airline

* Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic

Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic was an important area of dispute, and tensions between the Catholic hierarchy and the Republic were apparent from the beginning, eventually leading to the Catholic Church acting against the Republic and i ...

* Sanjurjada

* Electoral Carlism (Second Republic)

In terms of electoral success Carlism of the Second Spanish Republic remained a medium-small political grouping, by far outperformed by large parties like PSOE and CEDA though trailing behind also medium-large contenders like Izquierda Republicana. ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Raymond Carr, ed. ''The Republic and the Civil War in Spain'' (1971) * Raymond Carr, ''Spain 1808–1975'' (2nd ed. 1982)External links

Constitución de la República Española (1931)

English Translation of the Constitution of the Spanish Republic (1931)

* *

Video La II República Española

{{Authority control States and territories established in 1931 States and territories disestablished in 1939 Modern history of Spain Spanish Republic, Second Political history of Spain Republicanism in Spain 1931 establishments in Spain 1939 disestablishments in Spain Former countries of the interwar period