Repubbliche Marinare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were

The expression "maritime republics" refers to the Italian

The expression "maritime republics" refers to the Italian

ImageSize = width:1100 height:auto barincrement:20

PlotArea = top:10 bottom:50 right:130 left:20

AlignBars = late

DateFormat = yyyy

Period = from:800 till:1850

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:100 start:800

Colors =

id:Amalfi value:rgb(0.4,0,1) legend: Amalfi

id:Ancona value:rgb(1,0.9,0.1) legend: Ancona

id:Gaeta value:rgb(0.3,1,0.3) legend: Gaeta

id:Genoa value:rgb(1,0.6,0) legend: Genoa

id:Pisa value:rgb(0.3,0.8,1) legend: Pisa

id:Ragusa value:rgb(0.7,0.2,1) legend: Ragusa

id:Venice value:rgb(1,0.1,0.1) legend: Venice

id:Noli value:rgb(0.2,0.5,0) legend: Noli

Legend = columns:4 left:150 top:24 columnwidth:200

TextData =

pos:(20,27) textcolor:black fontsize:M

text:

BarData =

barset:PM

PlotData=

width:5 align:left fontsize:S shift:(5,-4) anchor:till

barset:PM

from:839 till:1131 color:Amalfi text:"

The maritime republics formed autonomous republican governments, an expression of the  The Crusades offered opportunities for expansion. They increasingly relied on Italian sea transport, for which the republics extracted concessions of colonies as well as a cash price. Venice, Amalfi, Ancona, and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the

The Crusades offered opportunities for expansion. They increasingly relied on Italian sea transport, for which the republics extracted concessions of colonies as well as a cash price. Venice, Amalfi, Ancona, and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the

Espansione di Amalfi.png, Expansion and influence of Amalfi

Espansione di Pisa.png, Expansion and influence of Pisa

Repubblica di Genova.png, Expansion and influence of Genoa

Repubblica di Venezia.png, Expansion and influence of Venice

Repubbliche marinare - fondachi anconitani.png, Trade routes of Ancona

Repubbliche marinare - fondachi e consolati ragusei.png, Trade routes of Ragusa

Genoese Holdings.png, Genoese Holdings in the 12th–13th century

Venetian Holdings.png, Venetian Holdings in the 15th–16th century

Pisan_Republic.png, Pisan Holdings in the 12th century

In 1016 an alliance of Pisa and Genoa defeated the Saracens, conquered Corsica and gained control of the

In 1016 an alliance of Pisa and Genoa defeated the Saracens, conquered Corsica and gained control of the  Pisa, at that time overlooking the sea at the mouth of the

Pisa, at that time overlooking the sea at the mouth of the

Genoa, also known as ''La Superba'' ("the Superb one"), began to gain autonomy from the

Genoa, also known as ''La Superba'' ("the Superb one"), began to gain autonomy from the

The fortunes of the town increased considerably when it joined the First Crusade: its participation brought great privileges for the Genoese colonists, which moved to many places in the

The fortunes of the town increased considerably when it joined the First Crusade: its participation brought great privileges for the Genoese colonists, which moved to many places in the

The Republic of

The Republic of

Included in the Papal States since 774,

Included in the Papal States since 774,

In the first half of the 7th century, Ragusa began to develop an active trade in the East Mediterranean. From the 11th century, it emerged as a maritime and mercantile city, especially in the Adriatic. The first known commercial contract goes back to 1148 and was signed with the city of

In the first half of the 7th century, Ragusa began to develop an active trade in the East Mediterranean. From the 11th century, it emerged as a maritime and mercantile city, especially in the Adriatic. The first known commercial contract goes back to 1148 and was signed with the city of  Ragusa was the door to the

Ragusa was the door to the

As Byzantine influence declined in Southern Italy the town began to grow. For fear of the

As Byzantine influence declined in Southern Italy the town began to grow. For fear of the

Gaeta

', in '' Guide Rosse'', Touring Club Italiano.

Towards the end of the 11th century, the

Towards the end of the 11th century, the

Conflict between the two Republics reached a violent crisis in the struggle at

Conflict between the two Republics reached a violent crisis in the struggle at

Towards the end of the 14th century,

Towards the end of the 14th century,

Around the mid-15th century, Genoa entered into a triple alliance with Florence and

Around the mid-15th century, Genoa entered into a triple alliance with Florence and

At the beginning of the second millennium, Muslim armies had advanced into

At the beginning of the second millennium, Muslim armies had advanced into

thalassocratic

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples ...

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s of the Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Being a significant presence in Italy in the Middle Ages

The history of Italy in the Middle Ages can be roughly defined as the time between the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance. The term "Middle Ages" itself ultimately derives from the description of the period of "obscu ...

, four of them have the coat of arms inserted in the flag of the Italian Navy since 1947: Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

, and Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

; the other republics are: Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

(now Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterran ...

), Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

, Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

,Peris Persi, in ''Conoscere l'Italia'', vol. Marche, Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara 1982 (p. 74); AA.VV. ''Meravigliosa Italia, Enciclopedia delle regioni'', edited by Valerio Lugoni, Aristea, Milano; Guido Piovene, in ''Tuttitalia'', Casa Editrice Sansoni, Firenze & Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara (p. 31); Pietro Zampetti, in ''Itinerari dell'Espresso'', vol. Marche, edited by Neri Pozza, Editrice L'Espresso, Rome, 1980 and the little Noli

Noli (; lij, Nöi ) is a coast ''comune'' of Liguria, Italy, in the Province of Savona, it is about southwest of Genoa by rail, about above sea-level. The origin of the name may come from ''Neapolis'', meaning "new city" in Greek.

From 1192 ...

.

From the 10th century, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in reestablishing contacts between Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, which had been interrupted during the early Middle Ages. These contacts were not only commercial, but also cultural and artistic. They also had an essential role in the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

.

Origins

The expression "maritime republics" refers to the Italian

The expression "maritime republics" refers to the Italian city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s which, since the Middle Ages, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity, thanks to their maritime activities. The economic growth of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

around the year 1000, together with the hazards of the mainland trading routes, made possible the development of major commercial routes along the Mediterranean coast. The growing independence acquired by some coastal cities gave them a leading role in this development. These cities, exposed to pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

raids (mostly Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

), organized their own defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense industr ...

, providing themselves substantial war fleets. Thus, in the 10th and 11th centuries they were able to switch to an offensive stance, taking advantage of the rivalry between the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and Islamic maritime powers and competing with them for control over commerce and trade routes to Asia and Africa.

They were generally republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

s and formally independent, though most of them originated from territories once formally belonging to the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(the main exceptions being Genoa and Pisa). During the time of their independence, all these cities had similar (though not identical) systems of government, in which the merchant class

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

had considerable power.

Amalfi, Ancona, Gaeta, Genoa, Venice and Ragusa began their own history of autonomy and trading after being almost destroyed by a terrible looting, or were founded by refugees from devastated lands.

The maritime republics became heavily involved in the Levantine Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

of the 10th to 13th centuries. They provided transport and support to Crusaders, and especially took advantage of the political and trading opportunities created by the conflict. The Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

of 1202–1204, originally intended to recapture Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, ultimately resulted in the Venetian conquest of Zara and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

.

Venice, Genoa and Pisa became regional states: they had dominion over vast lands of their region and over different overseas lands, including many Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

islands (especially Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

), lands on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

, Aegean, and Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

(Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

); Venice stands out from the rest in that it maintained enormous tracts of land in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

until as late as the mid-17th century. Amalfi, Ancona, Gaeta and Ragusa instead extended their domain only to a part of the territory of their region, configuring themselves as a city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

throughout the period of their history. All maritime republics, had commercial colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

and in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

; an exception is Noli, who used the Genoese ones.

The maritime republics over the centuries

Development

The history of the various maritime republics is quite varied, reflecting their different lifespans. Venice, Genoa, Noli, and Ragusa had very long lives, with an independence that outlasted the medieval period and continued up to the threshold of the contemporary era, when the Italian and European states were devastated by theNapoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Other republics kept their independence until the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

: Pisa came under the dominion of the Republic of Florence

The Republic of Florence, officially the Florentine Republic ( it, Repubblica Fiorentina, , or ), was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany. The republic originated in 1115, when the Flo ...

in 1406, and Ancona came under control of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

in 1532. Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

and Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

, though, lost their independence very soon: the first in 1131 and the second in 1140, both having passed into the hands of the Normans.

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1532 color:Ancona text:"Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

" fontsize:10

from:839 till:1137 color:Gaeta text:"Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

" fontsize:10

from:1005 till:1797 color:Genoa text:"Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1406 color:Pisa text:"Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

" fontsize:10

from:1050 till:1808 color:Ragusa text:"Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

" fontsize:10

from:1143 till:1797 color:Venice text:"Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

" fontsize:10

from:1192 till:1797 color:Noli text:"Noli

Noli (; lij, Nöi ) is a coast ''comune'' of Liguria, Italy, in the Province of Savona, it is about southwest of Genoa by rail, about above sea-level. The origin of the name may come from ''Neapolis'', meaning "new city" in Greek.

From 1192 ...

" fontsize:10

merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

class that constituted the backbone of their power. The history of the maritime republics intertwines both with the launch of European expansion to the East and with the origins of modern capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

as a mercantile and financial system. Using gold coins, the merchants of the Italian maritime republics began to develop new foreign exchange transactions and accounting. Technological advances in navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

provided essential support for the growth of mercantile wealth. Nautical charts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries all belong to the schools of Genoa, Venice and Ancona.

The Crusades offered opportunities for expansion. They increasingly relied on Italian sea transport, for which the republics extracted concessions of colonies as well as a cash price. Venice, Amalfi, Ancona, and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the

The Crusades offered opportunities for expansion. They increasingly relied on Italian sea transport, for which the republics extracted concessions of colonies as well as a cash price. Venice, Amalfi, Ancona, and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, but the phenomenon increased with the Crusades: thousands of Italians from the maritime republics poured into the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

and the Black Sea, creating bases, ports and commercial establishments known as "colonies". These were small gated enclaves within a city, often just a single street, where the laws of the Italian city were administered by a governor appointed from home, and there would be a church under home jurisdiction and shops with Italian styles of food. These Italian mercantile centers also exerted significant political influence locally: the Italian merchants formed guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

-like associations in their business centers, aiming to obtain legal, tax and customs privileges from foreign governments. Several personal dominions arose. Pera Pera may refer to:

Places

* Pera (Beyoğlu), a district in Istanbul formerly called Pera, now called Beyoğlu

** Galata, a neighbourhood of Beyoğlu, often referred to as Pera in the past

* Pêra (Caparica), a Portuguese locality in the district of ...

in Constantinople, first Genoese and later (under the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

) Venetian, was the largest and best known Italian trading base.

Amalfi

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

, perhaps the first of the maritime republics to play a major role, had developed extensive trade with Byzantium and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Amalfitan merchants wrested the Mediterranean trade monopoly from the Arabs and founded mercantile bases in Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

in the 10th century. Amalfitans were the first to create a colony in Constantinople.

Among the most important products of the Republic of Amalfi are the Amalfian Laws

The Amalfian Laws are a code of maritime laws compiled in the 12th century in Amalfi, a town in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in th ...

, a codification of the rules of maritime law which remained in force throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

.

From 1039 Amalfi came under the control of the Principality of Salerno

The Principality of Salerno ( la, Principatus Salerni) was a medieval Southern Italian state, formed in 851 out of the Principality of Benevento after a decade-long civil war. It was centred on the port city of Salerno. Although it owed alle ...

. In 1073 Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard (; Modern ; – 17 July 1085) was a Norman adventurer remembered for the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy, went on to become count and then duke of Apulia and Calabri ...

conquered the city, taking the title ''Dux Amalfitanorum'' ("Duke of the Amalfitans"). In 1096 Amalfi revolted and reverted to an independent republic, but this was put down in 1101. It revolted again in 1130 and was finally subdued in 1131.

Amalfi was sacked by Pisans in 1137, at a time when it was weakened by natural disasters (severe flooding) and was annexed to the Norman lands in southern Italy. Thereafter, Amalfi began a rapid decline and was replaced in its role as the main commercial hub of Campania

Campania (, also , , , ) is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islands and the i ...

by the Duchy of Naples

The Duchy of Naples ( la, Ducatus Neapolitanus, it, Ducato di Napoli) began as a Byzantine province that was constituted in the seventh century, in the reduced coastal lands that the Lombards had not conquered during their invasion of Italy in ...

.

Pisa

Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

. A century later they freed the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

in an expedition that was celebrated in the ''Gesta triumphalia per Pisanos'' and in the ''Liber Maiorichinus

The ''Liber maiolichinus'' ''de gestis pisanorum illustribus'' ("Majorcan Book of the Deeds of the Illustrious Pisans") is a Medieval Latin epic chronicle in 3,500 hexameters, written between 1117 and 1125, detailing the Pisan-led joint military ...

'' epic poem, composed in 1113–1115.

Arno

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a s ...

, reached the pinnacle of its glory between the 12th and 13th centuries, when its ships controlled the Western Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the eas ...

. Rivalry between Pisa and Genoa grew worse in the 12th century and resulted in the naval Battle of Meloria (1284)

The Battle of Meloria was fought near the islet of Meloria in the Ligurian Sea on 5 and 6 August 1284 between the fleets of the Republics of Genoa and Pisa as part of the Genoese-Pisan War. The victory of Genoa and the destruction of the Pisa ...

, which marked the beginning of Pisan decline; Pisa renounced all claim to Corsica and ceded part of Sardinia to Genoa in 1299. Moreover, the Aragonese conquest of Sardinia

The Aragonese conquest of Sardinia took place between 1323 and 1326. The island of Sardinia was at the time subject to the influence of the Republic of Pisa, the Pisan della Gherardesca family, Genoa and of the Genoese families of Doria and the ...

, which began in 1324, deprived the Tuscan city of dominion over the ''Giudicati

The Judicates (, or in Sardinian, in Latin, or in Italian), in English also referred to as Sardinian Kingdoms, Sardinian Judgedoms or Judicatures, were independent states that took power in Sardinia in the Middle Ages, between the ninth an ...

'' of Cagliari

Cagliari (, also , , ; sc, Casteddu ; lat, Caralis) is an Italian municipality and the capital of the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy. Cagliari's Sardinian name ''Casteddu'' means ''castle''. It has about 155,000 inhabitant ...

and Gallura

Gallura ( sdn, Gaddura or ; sc, Caddura ) is a region in North-Eastern Sardinia, Italy.

The name ''Gallùra'' is allegedly supposed to mean "stony area".

Geography

Gallùra has a surface of and it is situated between 40°55'20"64 latitude ...

. Pisa maintained its independence and control of the Tuscan coast until 1409, when it was annexed by Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

.

Genoa

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

around the 11th century, becoming a city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

with a republican constitution, and participating in the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

. Initially called ''Compagna Communis'', the denomination of ''republic'' was made official in 1528 on the initiative of Admiral Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Repu ...

.

The alliance with Pisa allowed the liberation of the western sector of the Mediterranean from Saracen pirates, with the reconquest of Corsica, the Balearics and Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

.

The formation of the ''Compagna Communis'', a meeting of all the city's trade association

A trade association, also known as an industry trade group, business association, sector association or industry body, is an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific Industry (economics), industry. An industry tra ...

s (''compagnie''), also comprising the noble lords of the surrounding valleys and coasts, finally signaled the birth of Genoese government.

The fortunes of the town increased considerably when it joined the First Crusade: its participation brought great privileges for the Genoese colonists, which moved to many places in the

The fortunes of the town increased considerably when it joined the First Crusade: its participation brought great privileges for the Genoese colonists, which moved to many places in the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

. The apex of Genoese fortune came in the 13th century with the conclusion of the Treaty of Nymphaeum (1261)

The Treaty of Nymphaeum was a trade and defense pact signed between the Empire of Nicaea and the Republic of Genoa in Nymphaion in March 1261. This treaty would have a major impact on both the restored Byzantine Empire and the Republic of Gen ...

with the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

. In exchange for aiding the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople

The Reconquest of Constantinople (1261) was the recapture of the city of Constantinople by the forces of the Empire of Nicaea, leading to the re-establishment of the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty, after an interval of 57 years ...

, this led to the ousting of the Venetians from the straits leading to the Black Sea, which quickly became a Genoese sea. Shortly afterwards, in 1284, Pisa was finally defeated in the Battle of Meloria

The Battle of Meloria was fought near the islet of Meloria in the Ligurian Sea on 5 and 6 August 1284 between the fleets of the Republics of Genoa and Pisa as part of the Genoese-Pisan War. The victory of Genoa and the destruction of the Pisan ...

by the Genoese Navy

The Genoese navy was the naval contingent of the Republic of Genoa's military. From the 11th century onward the Genoese navy protected the interests of the republic and projected its power throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas. It played a ...

.

In 1298 the Genoese defeated the Venetian fleet at the Dalmatian island of Curzola. The confrontation led to the capture of the Venetian Admiral and Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

, who during his imprisonment at the Palazzo San Giorgio

The Palazzo San Giorgio or Palace of St. George (also known as the Palazzo delle Compere di San Giorgio) is a palace in Genoa, Italy. It is situated in the Piazza Caricamento.

The palace was built in 1260 by Guglielmo Boccanegra, uncle of Simone ...

dictated the story of his travels to Rustichello da Pisa

Rustichello da Pisa, also known as Rusticiano (fl. late 13th century), was an Italian Romance (heroic literature), romance writer in Franco-Italian language. He is best known for co-writing Marco Polo's autobiography, ''The Travels of Marco Polo' ...

, his cellmate. Genoa remained relatively powerful until the last major conflict with Venice, the War of Chioggia

The War of Chioggia ( it, Guerra di Chioggia) was a conflict between Genoa and Venice which lasted from 1378 to 1381, from which Venice emerged triumphant. It was a part of the Venetian-Genoese Wars.

The war had mixed results. Venice and her alli ...

of 1379. It ended in victory for the Venetians, who finally regained dominance over trade to the East.

After a gloomy 15th century marked by plagues and foreign domination, the city regained self-government in 1528 through the efforts of Andrea Doria, who created a new constitution for Genoa. Throughout the following century Genoa became the primary sponsor of the Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, reaping huge profits, which allowed the old patrician

Patrician may refer to:

* Patrician (ancient Rome), the original aristocratic families of ancient Rome, and a synonym for "aristocratic" in modern English usage

* Patrician (post-Roman Europe), the governing elites of cities in parts of medieval ...

class to remain vital for a period. The Republic remained independent until 1797, when it was conquered by the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and replaced with the Ligurian Republic

The Ligurian Republic ( it, Repubblica Ligure, lij, Repubbrica Ligure) was a French client republic formed by Napoleon on 14 June 1797. It consisted of the old Republic of Genoa, which covered most of the Ligurian region of Northwest Italy, and ...

. After a brief revival in 1814, the Republic was ultimately annexed by the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

in 1815.

Venice

The Republic of

The Republic of Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, also known as ''La Serenissima'' (The Most Serene), came into being in 727 AD as a result of the development of trade relations with the Byzantine Empire, of which it was once formally a part, albeit with a substantial degree of independence. Venice remained an ally of Byzantium in the fight against Arabs and Normans. Around 1000 it began its expansion in the Adriatic, defeating the pirates who occupied the coast of Istria and Dalmatia and placing those regions and their principal townships under Venetian control. At the beginning of the 13th century, the city reached the peak of its power, dominating the commercial traffic in the Mediterranean and with the Orient. During the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

(1202–1204) its fleet was decisive in the acquisition of the islands and the most commercially important seaside towns of the Byzantine Empire. The conquest of the important ports of Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

(1207) and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

(1209) gave it a trade that extended to the east and reached Syria and Egypt, endpoints of maritime trading routes. By the end of the 14th century, Venice had become one of the richest states in Europe. Its dominance in the eastern Mediterranean in later centuries was threatened by the expansion of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in those areas, despite the great naval victory in the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

in 1571 against the Turkish fleet, fought with the Holy League

Commencing in 1332 the numerous Holy Leagues were a new manifestation of the Crusading movement in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers. Successful campaigns included the capture of Smyrna in 1344, at the Battle of ...

.

The Republic of Venice expanded strongly on the mainland, too. It became the largest of the maritime republics and was the most powerful state of Italy until 1797, when Napoleon invaded the Venetian lagoon and conquered Venice. The city passed between French and Austrian control over the next half-century, before briefly regaining its independence during the revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

. Austrian rule resumed a year later, and continued until 1866, when Veneto

Veneto (, ; vec, Vèneto ) or Venetia is one of the 20 regions of Italy. Its population is about five million, ranking fourth in Italy. The region's capital is Venice while the biggest city is Verona.

Veneto was part of the Roman Empire unt ...

passed into the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

.

Ancona

Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

came under the influence of the Holy Roman Empire around 1000, but gradually gained independence to become fully independent with the coming of the communes in the 12th century. Its motto was ('Dorian Ancona, city of faith'); its coin was the ''agontano''. Although somewhat confined by Venetian supremacy on the sea, Ancona was a notable maritime republic for its economic development and its preferential trade, particularly with the Byzantine Empire. Despite a series of expeditions, trade wars and naval blockades, Venice never succeeded in subduing Ancona.

The republic of Ancona enjoyed excellent relations with the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

and was an ally of the Republic of Ragusa.

* Francis F. Carter, ''Dubrovnik (Ragusa): A Classical City-state'', publisher: Seminar Press, London-New York, 1972 ;

* Robin Harris, ''Dubrovnik: A History'', publisher: Saqi Books, 2006. p. 127, Despite the link with Byzantium, it also maintained good relations with the Turks, enabling it to serve as central Italy's gateway to the Orient. The warehouses of the Republic of Ancona were continuously active in Constantinople, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and other Byzantine ports, while the sorting of goods imported by land (especially textiles and spices) fell to the merchants of Lucca

Lucca ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its province has a population of 383,957.

Lucca is known as one o ...

and Florence.

In art, Ancona was one of the centers of so-called Adriatic Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, that particular kind of renaissance that spread between Dalmatia, Venice and the Marches

Marche ( , ) is one of the twenty regions of Italy. In English, the region is sometimes referred to as The Marches ( ). The region is located in the central area of the country, bordered by Emilia-Romagna and the republic of San Marino to the ...

, characterized by a rediscovery of classical art

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic d ...

and a certain continuity with Gothic art

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern, Southern and ...

. The maritime cartographer Grazioso Benincasa

The Republic of Ancona was a medieval commune and maritime republic notable for its economic development and maritime trade, particularly with the Byzantine Empire and Eastern Mediterranean, although somewhat confined by Venetian supremacy on t ...

was born in Ancona, as was the navigator-archaeologist Cyriacus of Ancona

Cyriacus of Ancona or Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli (31 July 1391 – 1453/55) was a restlessly itinerant Italian humanist and antiquarian who came from a prominent family of merchants in Ancona, a maritime republic on the Adriatic. He has been called ...

, named by his fellow humanists "father of the antiquities", who made his contemporaries aware of the existence of the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, the Pyramids

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

, the Sphinx

A sphinx ( , grc, σφίγξ , Boeotian: , plural sphinxes or sphinges) is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of a falcon.

In Greek tradition, the sphinx has the head of a woman, the haunches of ...

and other famous ancient monuments believed destroyed.

Ancona always had to guard itself against the designs of both the Holy Roman Empire and the papacy. It never attacked other maritime cities, but was always forced to defend itself. It succeeded until 1532, when it lost its independence after Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

took possession of it by political means.

Ragusa

In the first half of the 7th century, Ragusa began to develop an active trade in the East Mediterranean. From the 11th century, it emerged as a maritime and mercantile city, especially in the Adriatic. The first known commercial contract goes back to 1148 and was signed with the city of

In the first half of the 7th century, Ragusa began to develop an active trade in the East Mediterranean. From the 11th century, it emerged as a maritime and mercantile city, especially in the Adriatic. The first known commercial contract goes back to 1148 and was signed with the city of Molfetta

Molfetta (; Molfettese: ) is a town located in the northern side of the Metropolitan City of Bari, Apulia, southern Italy.

It has a well restored old city, and its own dialect.

History

The earliest local signs of permanent habitation are at ...

, but other cities came along in the following decades, including Pisa, Termoli

Termoli (Neapolitan language, Molisano: ''Térmëlë'') is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south Adriatic coast of Italy, in the province of Campobasso, region of Molise. It has a population of around 32,000, having expanded quickly af ...

and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, Ragusa came under the dominion of the Republic of Venice, from which it inherited most of its institutions. Venetian rule lasted for one and a half centuries and determined the institutional structure of the future republic, with the emergence of the Senate in 1252 and the approval of the Ragusa Statute Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

on 9 May 1272. In 1358, following a war with the Kingdom of Hungary, the Treaty of Zadar

The Treaty of Zadar, also known as the Treaty of Zara, was a peace treaty signed in Zadar, Dalmatia on February 18, 1358 by which the Venetian Republic lost influence over its Dalmatian holdings. The Treaty of Zadar ended hostilities between Loui ...

forced Venice to give up many of its possessions in Dalmatia. Ragusa voluntarily became a dependency of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, obtaining the right to self-government in exchange for help with its fleet and payment of an annual tribute. Ragusa was fortified and equipped with two ports. The ''Communitas Ragusina'' began to be called ''Respublica Ragusina'' from 1403.

Basing its prosperity on maritime trade, Ragusa became the major power of the southern Adriatic and came to rival the Republic of Venice. For centuries Ragusa was an ally of Ancona, Venice's other rival in the Adriatic. This alliance enabled the two towns on opposite sides of the Adriatic to resist attempts by the Venetians to make the Adriatic a "Venetian bay", which would have given Venice direct or indirect control over all the Adriatic ports. The Venetian trade route went via Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

; Ancona and Ragusa developed an alternative route going west from Ragusa through Ancona to Florence and finally to Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

.

Ragusa was the door to the

Ragusa was the door to the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and the East, a place of commerce in metals, salt, spices and cinnabar

Cinnabar (), or cinnabarite (), from the grc, κιννάβαρι (), is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and ...

. It reached its peak during the 15th and 16th centuries thanks to tax exemptions for affordable goods. Its social structure was rigid, and the lower classes played no part in its government, but it was advanced in other ways: in the 14th century the first pharmacy was opened there, followed by a hospice; in 1418 the trafficking of slaves was abolished.

When the Ottoman Empire advanced into the Balkan Peninsula and Hungary was defeated in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526, Ragusa came formally under the supremacy of the sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

. It bound itself to pay him a symbolic annual tribute, a move that allowed it to maintain its effective independence.

The 17th century saw a slow decline of the Republic of Ragusa, due mainly to an earthquake in 1667 which razed much of the city, claiming 5000 victims, including the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

, Simone de Ghetaldi

Simone may refer to:

* Simone (given name), a feminine (or Italian masculine) given name of Hebrew origin

* Simone (surname), an Italian surname

Simone may also refer to:

* ''Simone'' (1918 film), a French silent drama film

* ''Simone'' (1926 fi ...

. The city was quickly rebuilt at the expense of the Pope and the kings of France and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, which made it a jewel of 17th-century urbanism, and the Republic enjoyed a short revival. The Treaty of Passarowitz

The Treaty of Passarowitz, or Treaty of Požarevac, was the peace treaty signed in Požarevac ( sr-cyr, Пожаревац, german: Passarowitz), a town that was in the Ottoman Empire but is now in Serbia, on 21 July 1718 between the Ottoman ...

of 1718 gave it full independence but increased the tax to be paid at the gate, set at 12,500 ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s.

The Peace of Pressburg of 1805 assigned the city to France. In 1806, the Republic was occupied by Napoleonic France

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eur ...

. The Republic was dissolved by order of General Auguste Marmont

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (20 July 1774 – 22 March 1852) was a French general and nobleman who rose to the rank of Marshal of the Empire and was awarded the title (french: duc de Raguse). In the Peninsular War Marmont succeede ...

on 31 January 1808 and was annexed to the Napoleonic Illyrian provinces

The Illyrian Provinces sl, Ilirske province hr, Ilirske provincije sr, Илирске провинције it, Province illirichegerman: Illyrische Provinzen, group=note were an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province of France d ...

. After a general insurrection against the occupation in 1813 and 1814, it was betrayed and occupied by its ally, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

.

Gaeta

Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century Germany in the Middle Ages, German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings, to refer ...

, in 840 the inhabitants of the neighbouring Formiæ fled to Gaeta. Though under the suzerainty ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' of Byzantium, Gaeta had then, ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'', a republican form of government with a ''dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, ''dux' ...

'', as a strong bulwark against Saracen invasion.Copied content from Duchy of Gaeta

The Duchy of Gaeta was an early medieval state centered on the coastal South Italian city of Gaeta. It began in the early ninth century as the local community began to grow autonomous as Byzantine power lagged in the Mediterranean and the penins ...

; see that page's history for attribution

The first consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

of Gaeta, Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

, who associated his son Marinus with him, defended the city from the ravages of saracens pirates and fortified it, building outlying castles as well. He was removed in 867, probably violently, by Docibilis I, who established a dynasty.

It was Docibilis II (died 954) who first took the title of ''dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, ''dux' ...

'' or duke (933). Docibilis saw Gaeta at its zenith.

Gaeta declined in importance in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. The Norman overlords of Gaeta appointed dukes from various families of local prominence, Normans mostly, until 1140, when the last Gaetan duke died, leaving the city to the Norman Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 unt ...

.Salvatore Aurigemma, Angelo de Santis, ''Gaeta, Formia, Minturno'', Istituto poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato, 1964 .

''Lazio'', chapter Gaeta

', in '' Guide Rosse'', Touring Club Italiano.

Relationships

Relationships between the maritime republics were governed by their commercial interests, and were often expressed as political or economic agreements aimed at shared profit from a trade route or mutual non-interference. But competition for control of the trade routes to the East and in the Mediterranean sparked rivalries that could not be settled diplomatically, and there were several clashes among the maritime republics.Pisa and Venice

Towards the end of the 11th century, the

Towards the end of the 11th century, the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

in the Holy Land began on the initiative of Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

, supported by the speeches of Peter the Hermit

Peter the Hermit ( 1050 – 8 July 1115 or 1131), also known as Little Peter, Peter of Amiens ( fr. ''Pierre d'Amiens'') or Peter of Achères ( fr. ''Pierre d'Achères''), was a Roman Catholic priest of Amiens and a key figure during the militar ...

. Venice and Pisa entered the crusade almost simultaneously, and the two republics were soon in competition. The Venetian naval army of bishop Eugenio Contarini

Eugenio is an Italian and Spanish masculine given name deriving from the Greek ' Eugene'. The name is Eugénio in Portuguese and Eugênio in Brazilian Portuguese.

The name's translated literal meaning is well born, or of noble status. Similar de ...

clashed with the Pisan army of Archbishop Dagobert

Dagobert or Taginbert is a Germanic male given name, possibly from Old Frankish ''Dag'' "day" and ''beraht'' "bright".

Alternatively, it has been identified as Gaulish ''dago'' "good" ''berxto'' "bright".

Animals

* Roi Dagobert (born 1964), t ...

in the sea around Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

. Pisa and Venice gave support to the Siege of Jerusalem by the army led by Godfrey of Bouillon

Godfrey of Bouillon (, , , ; 18 September 1060 – 18 July 1100) was a French nobleman and pre-eminent leader of the First Crusade. First ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1099 to 1100, he avoided the title of king, preferring that of princ ...

. The Pisan force remained in the Holy Land. Daibert became the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem

The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem ( la, Patriarchatus Latinus Hierosolymitanus) is the Latin Catholic ecclesiastical patriarchate in Jerusalem, officially seated in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It was originally established in 1099, wit ...

and crowned Godfrey of Bouillon

Godfrey of Bouillon (, , , ; 18 September 1060 – 18 July 1100) was a French nobleman and pre-eminent leader of the First Crusade. First ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1099 to 1100, he avoided the title of king, preferring that of princ ...

first Christian King of Jerusalem

The King of Jerusalem was the supreme ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state founded in Jerusalem by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade, when the city was conquered in 1099.

Godfrey of Bouillon, the first ruler of th ...

. Venice, in contrast, soon ended its participation in the first crusade, probably because its interests lay mainly in balancing Pisan and Genoese influence in the Orient.

Relationships between Pisa and Venice were not always characterized by rivalry and antagonism. Over the centuries, the two republics signed several agreements concerning their zones of influence and action, to avoid hindering each other. On 13 October 1180 the Doge of Venice and a representative of the Pisan consuls signed an agreement for the reciprocal non-interference in Adriatic and Tyrrhenian affairs, and in 1206 Pisa and Venice concluded a treaty in which they reaffirmed the respective zones of influence. Between 1494 and 1509, during the siege of Pisa by Florence, Venice went to rescue of the Pisans, following a policy of safeguarding Italian territory from foreign intervention.

Venice and Genoa

The relationship between Genoa and Venice was almost continuously competitive and hostile, both economically and militarily. Until the beginning of the 13th century, hostilities were limited to rare acts of piracy and isolated skirmishes. In 1218 Venice and Genoa reached an agreement to end the piracy and to safeguard each other. Genoa was guaranteed the right to trade in the eastern imperial lands, a new and profitable market.War of Saint Sabas and the conflict of 1293–99

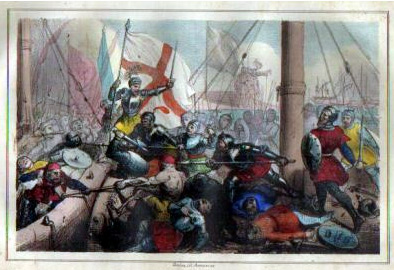

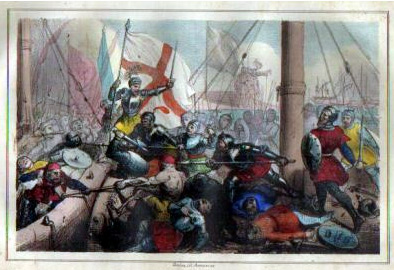

Conflict between the two Republics reached a violent crisis in the struggle at

Conflict between the two Republics reached a violent crisis in the struggle at Saint-Jean d'Acre

Acre ( ), known locally as Akko ( he, עַכּוֹ, ''ʻAkō'') or Akka ( ar, عكّا, ''ʻAkkā''), is a city in the coastal plain region of the Northern District of Israel.

The city occupies an important location, sitting in a natural harb ...

for ownership of the Saint Sabas monastery

The Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas, known in Arabic and Syriac as Mar Saba ( syr, ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܣܒܐ, ar, دير مار سابا; he, מנזר מר סבא; el, Ἱερὰ Λαύρα τοῦ Ὁσίου Σάββα τοῦ Ἡγιασμέ� ...

. The Genoese occupied it in 1255, beginning hostilities with the sacking of the Venetian neighbourhood and the destruction of the ships docked there. Venice first agreed to an alliance with Pisa regarding their common interests in Syria and Palestine, but then counter-attacked, destroying the fortified monastery. The flight of the Genoese and of the baron Philip of Montfort, ruler of the Christian principality of Syria, concluded the first phase of the punitive expedition.

Just one year later, the three maritime powers fought an uneven conflict in the waters facing Saint-Jean d'Acre. Almost all the Genoese galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s were sunk and 1,700 fighters and sailors were killed. The Genoese replied with new alliances. The Nicaean throne was usurped by Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

, that aimed at reconquest of the lands once owned by the Byzantine Empire. His expansionist project suited the Genoese. The Nicaean fleet and army conquered and occupied Constantinople, causing the collapse of the Latin Empire of Constantinople

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzanti ...

less than sixty years after its creation. Genoa replaced Venice in the monopoly of commerce with the Black Sea territories.

This period of conflict between Genoa and Venice ended with the Battle of Curzola of 1298 (won by Genoa), in which the Venetian admiral Andrea Dandolo was taken prisoner. To avoid the shame of arriving in Genoa in shackles, Dandolo committed suicide by smashing his head against the oar to which he was tied. A year later, the Republics signed a peace treaty in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

.

War of Chioggia

Towards the end of the 14th century,

Towards the end of the 14th century, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

was occupied by the Genoese and ruled by the ''signoria

A signoria () was the governing authority in many of the Italian city states during the Medieval and Renaissance periods.

The word signoria comes from ''signore'' , or "lord"; an abstract noun meaning (roughly) "government; governing authority; ...

'' of Pietro II of Lusignano

Peter II (1354 or 1357 – 13 October 1382), called the Fat (French ''Pierre le Gros''), was the eleventh King of Cyprus of the House of Lusignan from 17 January 1369 until his death. Peter W. Edbury: The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades 1191� ...

, while the smaller island of Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

, an important port of call on the Bosphorous

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

and Black Sea route, was conceded by Andronikos IV Palaiologos

Andronikos IV Palaiologos or Andronicus IV Palaeologus ( gr, Ἀνδρόνικος Παλαιολόγος; 11 April 1348 – 25/28 June 1385) was the eldest son of Emperor John V Palaiologos. Appointed co-emperor since 1352, he had a troubled rel ...

to Genoa in place of the concession of his father John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, ''Iōánnēs Palaiológos''; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions.

Biography

John V was the son of E ...

to Venice. These two events fuelled the resumption of hostilities between the two maritime Republics, which were expanding from the east to the west of the Mediterranean.

The conflict was named the War of Chioggia

The War of Chioggia ( it, Guerra di Chioggia) was a conflict between Genoa and Venice which lasted from 1378 to 1381, from which Venice emerged triumphant. It was a part of the Venetian-Genoese Wars.