Representative Peers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

Under articles XXII and XXIII of the

Under articles XXII and XXIII of the  Counsel for the Government held a different view. It was noted that the Peerage Act 1963 explicitly repealed the portions of the Articles of Union relating to elections of representative peers, and that no parliamentary commentators had raised doubts as to the validity of those repeals. As Article XXII had been, or at least purportedly, repealed, there was nothing specific in the Treaty that the bill transgressed. It was further asserted by the Government that Article XXII could be repealed because it had not been entrenched. Examples of entrenched provisions are numerous: England and Scotland were united "forever", the Court of Session was to remain "in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted", and the establishment of the

Counsel for the Government held a different view. It was noted that the Peerage Act 1963 explicitly repealed the portions of the Articles of Union relating to elections of representative peers, and that no parliamentary commentators had raised doubts as to the validity of those repeals. As Article XXII had been, or at least purportedly, repealed, there was nothing specific in the Treaty that the bill transgressed. It was further asserted by the Government that Article XXII could be repealed because it had not been entrenched. Examples of entrenched provisions are numerous: England and Scotland were united "forever", the Court of Session was to remain "in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted", and the establishment of the

Irish representation in the Westminster parliament was outlined by articles IV and VIII of the agreement embodied in the

Irish representation in the Westminster parliament was outlined by articles IV and VIII of the agreement embodied in the  Following the establishment of the

Following the establishment of the

Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third. Volume 1

' Boston: Crosby and Nichols. * *

Anglo-Irish Treaty, 6 December 1921. The National Archives of Ireland. Retrieved 2007-04-07

Briefing Paper: Membership of House of Lords

(pdf). House of Lords, 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-31 * ''Peerage'' (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. London: Cambridge University Press.

House of Lords, 18 October 1999. Retrieved 2007-04-07 {{DEFAULTSORT:Representative Peer Elections in Scotland Political history of Ireland Politics of Scotland * Peerages in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, representative peers were those peers

Peers may refer to:

People

* Donald Peers

* Edgar Allison Peers, English academician

* Gavin Peers

* John Peers, Australian tennis player

* Kerry Peers

* Mark Peers

* Michael Peers

* Steve Peers

* Teddy Peers (1886–1935), Welsh international ...

elected by the members of the Peerage of Scotland

The Peerage of Scotland ( gd, Moraireachd na h-Alba, sco, Peerage o Scotland) is one of the five divisions of peerages in the United Kingdom and for those peers created by the King of Scots before 1707. Following that year's Treaty of Union, ...

and the Peerage of Ireland

The Peerage of Ireland consists of those titles of nobility created by the English monarchs in their capacity as Lord or King of Ireland, or later by monarchs of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It is one of the five divisi ...

to sit in the British House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

. Until 1999, all members of the Peerage of England

The Peerage of England comprises all peerages created in the Kingdom of England before the Act of Union in 1707. In that year, the Peerages of England and Scotland were replaced by one Peerage of Great Britain. There are five peerages in t ...

held the right to sit in the House of Lords; they did not elect a limited group of representatives. All peers who were created after 1707 as Peers of Great Britain and after 1801 as Peers of the United Kingdom held the same right to sit in the House of Lords.

Representative peers were introduced in 1707, when the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

and the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

were united into the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

. At the time there were 168 English and 154 Scottish peers. The English peers feared that the House of Lords would be swamped by the Scottish element, and consequently the election of a small number of representative peers to represent Scotland was negotiated. A similar arrangement was adopted when the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label=Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

merged into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Great B ...

in January 1801.

Scotland was allowed to elect sixteen representative peers, while Ireland could elect twenty-eight. Those chosen by Scotland sat for the life of one Parliament, and following each dissolution new Scottish peers were elected. In contrast, Irish representative peers sat for life. Elections for Irish peers ceased when the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

came into existence as a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

in December 1922. However, already-elected Irish peers continued to be entitled to sit until their death. Elections for Scottish peers ended in 1963, when all Scottish peers obtained the right to sit in the House of Lords.

Under the House of Lords Act 1999

The House of Lords Act 1999 (c. 34) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the House of Lords, one of the chambers of Parliament. The Act was given Royal Assent on 11 November 1999. For centuries, the House of Lords ...

, a new form of representative peer was introduced to allow some hereditary peers to stay in the House of Lords.

Scotland

Under articles XXII and XXIII of the

Under articles XXII and XXIII of the Act of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

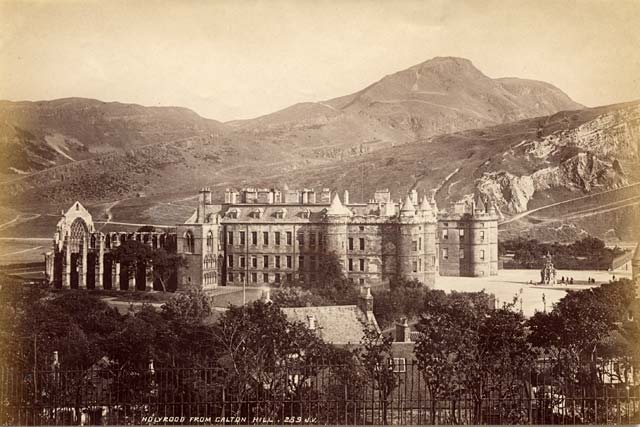

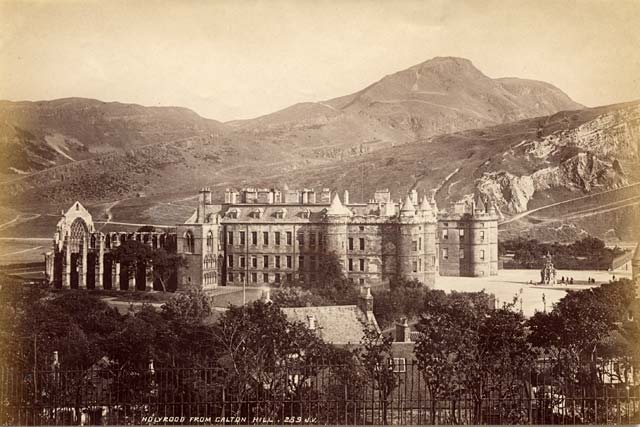

, Scottish peers were entitled to elect sixteen representative peers to the House of Lords. Each served for one Parliament or a maximum of seven years, but could be re-elected during future Parliaments. Upon the summons of a new Parliament, the Sovereign would issue a proclamation summoning Scottish peers to the Palace of Holyroodhouse

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh ...

. The elections were held in the Great Gallery, a large room decorated by eighty-nine of Jacob de Wet's portraits of Scottish monarchs, from Fergus Mór

Fergus Mór mac Eirc ( gd, Fearghas Mòr Mac Earca; English: ''Fergus the Great'') was a possible king of Dál Riata. He was the son of Erc of Dalriada.

While his historicity may be debatable, his posthumous importance as the founder of Scotl ...

to Charles II. The Lord Clerk Register

The office of Lord Clerk Register is the oldest surviving Great Officer of State in Scotland, with origins in the 13th century. It historically had important functions in relation to the maintenance and care of the public records of Scotland. To ...

would read out the Peerage Roll as indicates his presence when called. The Roll was then re–read, with each peer responding by publicly announcing his votes and the return being sent to the clerk of the crown at London. The same procedure was used whenever a vacancy arose.

The block voting

Block voting or bloc voting refers to electoral systems in which multiple candidates are elected at once and a group (voting bloc) of voters can force the system to elect only their preferred candidates. Block voting may be used at large (in a si ...

system was used, with each peer casting as many votes as there were seats to be filled. The system, however, permitted the party with the greatest number of peers, normally the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, to procure a disproportionate number of seats, with opposing parties sometimes being left entirely unrepresented. The Lord Clerk Register was responsible for tallying the votes. The return issued by the Lord Clerk Register was sufficient evidence to admit the representative peers to Parliament; however, unlike other peers, Scottish representatives did not receive writs of summons.

The position and rights of Scottish peers in relation to the House of Lords remained unclear during most of the eighteenth century. In 1711, The 4th Duke of Hamilton, a peer of Scotland, was made Duke of Brandon

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

in the Peerage of Great Britain

The Peerage of Great Britain comprises all extant peerages created in the Kingdom of Great Britain between the Acts of Union 1707 and the Acts of Union 1800. It replaced the Peerage of England and the Peerage of Scotland, but was itself r ...

. When he sought to sit in the House of Lords, he was denied admittance, the Lords ruling that a peer of Scotland could not sit in the House of Lords unless he was a representative peer, even if he also held a British peerage dignity. They reasoned that the Act of Union 1707 had established the number of Scots peers in the House of Lords at no more and no less than sixteen. In 1782, however, the House of Lords reversed the decision, holding that the Crown could admit anyone it pleases to the House of Lords, whether a Scottish peer or not, subject only to qualifications such as being of full age.

Under the Peerage Act 1963

The Peerage Act 1963 (c. 48) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that permits women peeresses and all Scottish hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and allows newly inherited hereditary peerages to be disclaimed.

Backgro ...

, all Scottish peers procured the right to sit in the House of Lords, and the system of electing representative peers was abolished. Scottish as well as British and English hereditary peer

The hereditary peers form part of the peerage in the United Kingdom. As of September 2022, there are 807 hereditary peers: 29 dukes (including five royal dukes), 34 marquesses, 190 earls, 111 viscounts, and 443 barons (disregarding subsid ...

s lost their automatic right to sit in the Upper House with the passage of the House of Lords Act 1999

The House of Lords Act 1999 (c. 34) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the House of Lords, one of the chambers of Parliament. The Act was given Royal Assent on 11 November 1999. For centuries, the House of Lords ...

. During the debate on the House of Lords Bill, a question arose as to whether the proposal would violate the Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

. In suggesting that the Bill did indeed violate the Articles of Union, it was submitted that, prior to Union, the Estates of Parliament, Scotland's old, pre-Union parliament, was entitled to impose conditions, and that one fundamental condition was a guarantee of representation of Scotland in both Houses of Parliament at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

. It was implied, furthermore, that the Peerage Act 1963 did not violate the requirement of Scottish representation, set out in the Article XXII of the Treaty of Union, by allowing all Scottish peers to sit in the House of Lords: as long as a minimum of sixteen seats were reserved for Scotland, the principles of the Article would be upheld. It was further argued that the only way to rescind the requirement of Article XXII would be to dissolve the Union between England and Scotland, which the House of Lords Bill did not seek to do.

Counsel for the Government held a different view. It was noted that the Peerage Act 1963 explicitly repealed the portions of the Articles of Union relating to elections of representative peers, and that no parliamentary commentators had raised doubts as to the validity of those repeals. As Article XXII had been, or at least purportedly, repealed, there was nothing specific in the Treaty that the bill transgressed. It was further asserted by the Government that Article XXII could be repealed because it had not been entrenched. Examples of entrenched provisions are numerous: England and Scotland were united "forever", the Court of Session was to remain "in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted", and the establishment of the

Counsel for the Government held a different view. It was noted that the Peerage Act 1963 explicitly repealed the portions of the Articles of Union relating to elections of representative peers, and that no parliamentary commentators had raised doubts as to the validity of those repeals. As Article XXII had been, or at least purportedly, repealed, there was nothing specific in the Treaty that the bill transgressed. It was further asserted by the Government that Article XXII could be repealed because it had not been entrenched. Examples of entrenched provisions are numerous: England and Scotland were united "forever", the Court of Session was to remain "in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted", and the establishment of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

was "effectually and unalterably secured". Article XXII, however, did not include any words of entrenchment, making it "fundamental or unalterable in all time coming".

Further, the Government pointed out that, even if the election of Scottish peers were entrenched, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

could amend the provision under the doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty

Parliamentary sovereignty, also called parliamentary supremacy or legislative supremacy, is a concept in the constitutional law of some parliamentary democracies. It holds that the legislative body has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over all ...

. Though the position of the Church of Scotland was "unalterably" secured, the Universities (Scotland) Act 1853 repealed the requirement that professors declare their faith before assuming a position. In Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

was entirely disestablished in 1869, though the Articles of Union with Ireland had clearly entrenched the establishment of that body. In December 1922, the Union with most of Ireland was dissolved upon the creation of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

, though Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and all of Ireland were supposedly united "forever." It was therefore suggested that Parliament could, if it pleased, repeal an Article of Union as well amend as any underlying principle.

The Privileges Committee unanimously found that the Articles of Union would not be breached by the House of Lords Bill if it were enacted. The bill did receive Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

, and from 1999, hereditary peers have not had the automatic right to sit in Parliament.

Ireland

Irish representation in the Westminster parliament was outlined by articles IV and VIII of the agreement embodied in the

Irish representation in the Westminster parliament was outlined by articles IV and VIII of the agreement embodied in the Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Irela ...

, which also required the Irish Parliament to pass an act before the union providing details for implementation.

Irish peers were allowed to elect twenty-eight representative peers as Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but n ...

, each of whom could serve for life. The Chamber of the Irish House of Lords

The Irish House of Lords was the upper house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from medieval times until 1800. It was also the final court of appeal of the Kingdom of Ireland.

It was modelled on the House of Lords of England, with membe ...

, located in Parliament House on College Green in central Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, housed the first election, attended by the peers or their proxies. The government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

mistakenly circulated a list of the successful candidates before the vote. The Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper

The Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper was a civil servant within the Irish Chancery in the Dublin Castle administration. His duties corresponded to the offices of Clerk of the Crown and Clerk of the Hanaper in the English Chancery. Latterly, the o ...

in Ireland was responsible for electoral arrangements; each peer voted by an open and public ballot. After the Union, new elections were held by postal vote

Postal voting is voting in an election where ballot papers are distributed to electors (and typically returned) by post, in contrast to electors voting in person at a polling station or electronically via an electronic voting system.

In an el ...

within 52 days of a vacancy.Malcomson 2000 p.313 Vacancies arose through death or, in the case of Baron Ashtown

Baron Ashtown, of Moate in the County of Galway, is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1800 for Frederick Trench, with remainder to the heirs male of his father.

Trench had previously represented Portarlington from 1798 in th ...

in 1915, bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor ...

. No vacancy was created where a representative peer acquired a UK peerage, as when Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

was made Baron Scarsdale

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

in 1911.

The Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

of Great Britain—the presiding officer of the House of Lords—certified the vacancy, while the Lord Chancellor of Ireland directed the Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper to issue ballots to Irish peers, receive the completed ballots, determine the victor, and announce the result, which was then published in both ''The Dublin Gazette

''The Dublin Gazette'' was the gazette, or official newspaper, of the Dublin Castle administration, Irish Executive, Britain's government in Ireland based at Dublin Castle, between 1705 and 1922. It published notices of government business, inclu ...

'' and ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are ...

''. Roman Catholic peers could not vote or stand for election until the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

.Malcomson (2000) p. 311 The process of being recognised by the Westminster Committee of Privileges

The Commons Select Committee of Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to consider specific matters relating to privileges referred to it by the House.

It came into being on 7 January 2013 as one half of the replacements for the Committ ...

as an elector was more cumbersome and expensive than being recognised as a (British or Irish) peer, until the orders drawn up in 1800 were amended in 1857. Successive governments tried to prevent the election of absentee landlords

In economics, an absentee landlord is a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. The term "absentee ownership" was popularised by economist Thorstein Veblen's 1923 bo ...

. An exception was Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, who won election as a representative peer in 1908, despite never having claimed the right to be an elector; he had been refused a peerage of the United Kingdom by the Liberal government of the day.

The Acts of Union united the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

and Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

, whose bishops and archbishops had previously sat as Lords Spiritual in their respective Houses of Lords. In the united Parliament, there were at first four Irish prelates at any one time, one archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

and three diocesan bishops, who sat for a session before ceding their seats to colleagues on a fixed rotation of dioceses

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

. The rotation passed over any bishop already serving as an elected representative peer, as when Charles Agar sat as Viscount Somerton

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a Title#Aristocratic titles, title used in certain European countries for a nobility, noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-he ...

rather than as Archbishop of Dublin. The rotation was changed by the Church Temporalities Act 1833

The Church Temporalities Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. 4 c. 37), sometimes called the Church Temporalities (Ireland) Act 1833, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland which undertook a major reorganisation of the Ch ...

, which merged many dioceses and degraded the archbishoprics of Tuam

Tuam ( ; ga, Tuaim , meaning 'mound' or 'burial-place') is a town in Ireland and the second-largest settlement in County Galway. It is west of the midlands of Ireland, about north of Galway city. Humans have lived in the area since the Bronz ...

and Cashel to bishoprics. No Irish bishops sat in Westminster as Lords Spiritual after the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1871, brought about by the Irish Church Act 1869

The Irish Church Act 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 42) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which separated the Church of Ireland from the Church of England and disestablished the former, a body that commanded the adherence of a small min ...

, although Robin Eames

Robert Henry Alexander Eames, Baron Eames, (born 27 April 1936) is an Anglican bishop and life peer, who served as Primate of All Ireland and Archbishop of Armagh from 1986 to 2006.

Early life and education

Eames was born in 1936, the son ...

was made a life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. In modern times, life peerages, always created at the rank of baron, are created under the Life Peerages ...

in 1995 while Archbishop of Armagh.

Following the establishment of the

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

in December 1922, Irish peers ceased to elect representatives, although those already elected continued to have the right to serve for life; the last of the temporal peers, Francis Needham, 4th Earl of Kilmorey

Captain Francis Charles Adelbert Henry Needham, 4th Earl of Kilmorey (26 November 1883 – 11 January 1961), styled Viscount Newry until 1915, was a Royal Navy officer and Anglo-Irish peer.

In 1916 he was appointed as an Irish representative ...

, by chance a peer from an Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

family, died in 1961. Disputes had arisen long before as to whether Irish representative peers could still be elected. The main Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 was silent on the matter, to some seeming to mean that the right had not been abolished, but the ancillary Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act 1922

The Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act 1922 (Session 2) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed on 5 December 1922. The Act dealt with a number of matters concerning the Irish Free State, which was established on ...

had abolished the office of Lord Chancellor of Ireland, whose involvement was required in the election process. The Irish Free State abolished the office of Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper in 1926, the last holder becoming Master of the High Court. After 1922 various Irish peers petitioned the House of Lords for a restoration of their right to elect representatives. In 1962, the Joint Committee on House of Lords Reform again rejected such requests. In the next year, when the Peerage Act 1963

The Peerage Act 1963 (c. 48) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that permits women peeresses and all Scottish hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and allows newly inherited hereditary peerages to be disclaimed.

Backgro ...

(which, among other things, gave all peers in the Peerage of Scotland

The Peerage of Scotland ( gd, Moraireachd na h-Alba, sco, Peerage o Scotland) is one of the five divisions of peerages in the United Kingdom and for those peers created by the King of Scots before 1707. Following that year's Treaty of Union, ...

the right to sit in the House of Lords) was being considered, an amendment similarly to allow Irish peers all to be summoned was defeated, by ninety votes to eight. Instead, the new Act confirmed the right of all Irish peers to stand for election to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

and to vote at parliamentary elections, which were rights they had always had.

In 1965, the 8th Earl of Antrim, another peer from Ulster, and other Irish peers, petitioned the House of Lords, arguing that the right to elect representative peers had never been formally abolished. The House of Lords ruled against them. Lord Reid, a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, based his ruling on the Act of Union, which stated that representative peers sat "on the part of Ireland." He reasoned that, since the island had been divided into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, there was no such political entity called "Ireland" which the representative peers could be said to represent. Lord Reid wrote, "A statutory provision is impliedly repealed if a later enactment brings to an end a state of things the continuance of which is essential for its operation." In contrast, Lord Wilberforce

Richard Orme Wilberforce, Baron Wilberforce, (11 March 1907 – 15 February 2003) was a British judge. He was a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary from 1964 to 1982.

Early life and career

Born in Jalandhar, India, Richard Wilberforce was the son of ...

, another Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, disagreed that a major enactment such as the Act of Union could be repealed by implication. He argued instead that since the posts of Lord Chancellor of Ireland and Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper had been abolished, there was no mechanism by which Irish peers could be elected. Here too, the petitioners lost.

The petitioners failed to raise the status of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

as part of the United Kingdom. Charles Lysaght

Charles Lysaght (born 23 September 1941) is an Irish lawyer, biographer, and occasional columnist.

Legal career

Lysaght was born in Dublin on 23 September 1941. He was educated at St Michael's College, Dublin and Gonzaga College. He read law an ...

suggests that if this fact had been foremost, Lord Wilberforce's arguments relating to the removal of the electoral mechanism for the election could be rebutted, as the Lord Chancellor of Ireland and the Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper did have successors in Northern Ireland. The reason for excluding the arguments relating to Northern Ireland from the petition "was that leading counsel for the petitioning Irish peers was convinced that the members of the Committee for Privileges were with him on what he considered was his best argument and did not want to alienate them by introducing another point." To prevent further appeals on the matter, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

repealed, as a part of the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1971, the sections of the Acts of Union relating to the election of Irish representative peers.

House of Commons

After the Union of England and Scotland in 1707, Scottish peers, including those who did not sit as representative peers, were excluded from theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

. Irish peers were not subject to the same restrictions. Irish members not nominated as representative peers were allowed to serve in Parliament as representatives of constituencies in Great Britain, although not in Ireland, provided they gave up their privileges as a peer. Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, for example, specifically requested an Irish peerage when made Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, so that he would not be debarred from sitting in the House of Commons on his return.

The Peerage Act 1963 allowed all Scottish peers to sit in the House of Lords; it also permitted all Irish peers to sit in the House of Commons for any constituency in the United Kingdom, as well as to vote in parliamentary elections, without being deprived of the remaining privileges of peerage.

Hereditary "representative peers"

During the passage of the House of Lords Bill in 1999, controversy surrounding House of Lords reform remained, and the Bill was conceived as a first stage of Lords reform. The "Weatherill" amendment—so called since it was proposed by former House of Commons SpeakerBernard Weatherill

Bruce Bernard Weatherill, Baron Weatherill, (25 November 1920 – 6 May 2007) was a British Conservative Party politician. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons between 1983 and 1992.

Family

He was the son of Bernard Bruce Weatherill ...

—provided for a number of hereditary peers to remain as members of the House of Lords, during the first stage of Lords reform. It could then be reviewed during the next stage of the reform, when the system of appointed life peerages came under examination. In exchange for the House not delaying the passage of the Bill into law, the Government agreed to this amendment, and it then became part of the House of Lords Act 1999

The House of Lords Act 1999 (c. 34) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the House of Lords, one of the chambers of Parliament. The Act was given Royal Assent on 11 November 1999. For centuries, the House of Lords ...

, and 92 hereditary peers were allowed to remain.

The ninety-two peers are made up of three separate groups. Fifteen 'office-holders' comprise Deputy Speakers and Deputy Chairmen, and are elected by the House, while seventy-five party and Crossbench members are elected by their own party or group. In addition, there are two royal appointments: the Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable of England, Lord Hi ...

, currently Lord Carrington

Peter Alexander Rupert Carington, 6th Baron Carrington, Baron Carington of Upton, (6 June 1919 – 9July 2018), was a British Conservative Party politician and hereditary peer who served as Defence Secretary from 1970 to 1974, Foreign Secret ...

, is appointed as the King's representative in Parliament, while the post of Earl Marshal

Earl marshal (alternatively marschal or marischal) is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England (then, following the Act of Union 1800, in the United Kingdom). He is the eig ...

remains purely hereditary; the office has been held since 1672 by the Dukes of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

and is responsible for ceremonies such as the State Opening of Parliament.

Notes

Sources

* * Farnborough, Thomas. Erskine. May, 1st Baron. (1863)Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third. Volume 1

' Boston: Crosby and Nichols. * *

Anglo-Irish Treaty, 6 December 1921. The National Archives of Ireland. Retrieved 2007-04-07

Briefing Paper: Membership of House of Lords

(pdf). House of Lords, 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-31 * ''Peerage'' (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. London: Cambridge University Press.

House of Lords, 18 October 1999. Retrieved 2007-04-07 {{DEFAULTSORT:Representative Peer Elections in Scotland Political history of Ireland Politics of Scotland * Peerages in the United Kingdom