Reims, France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Reims ( ; ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the

Before the Roman conquest of northern

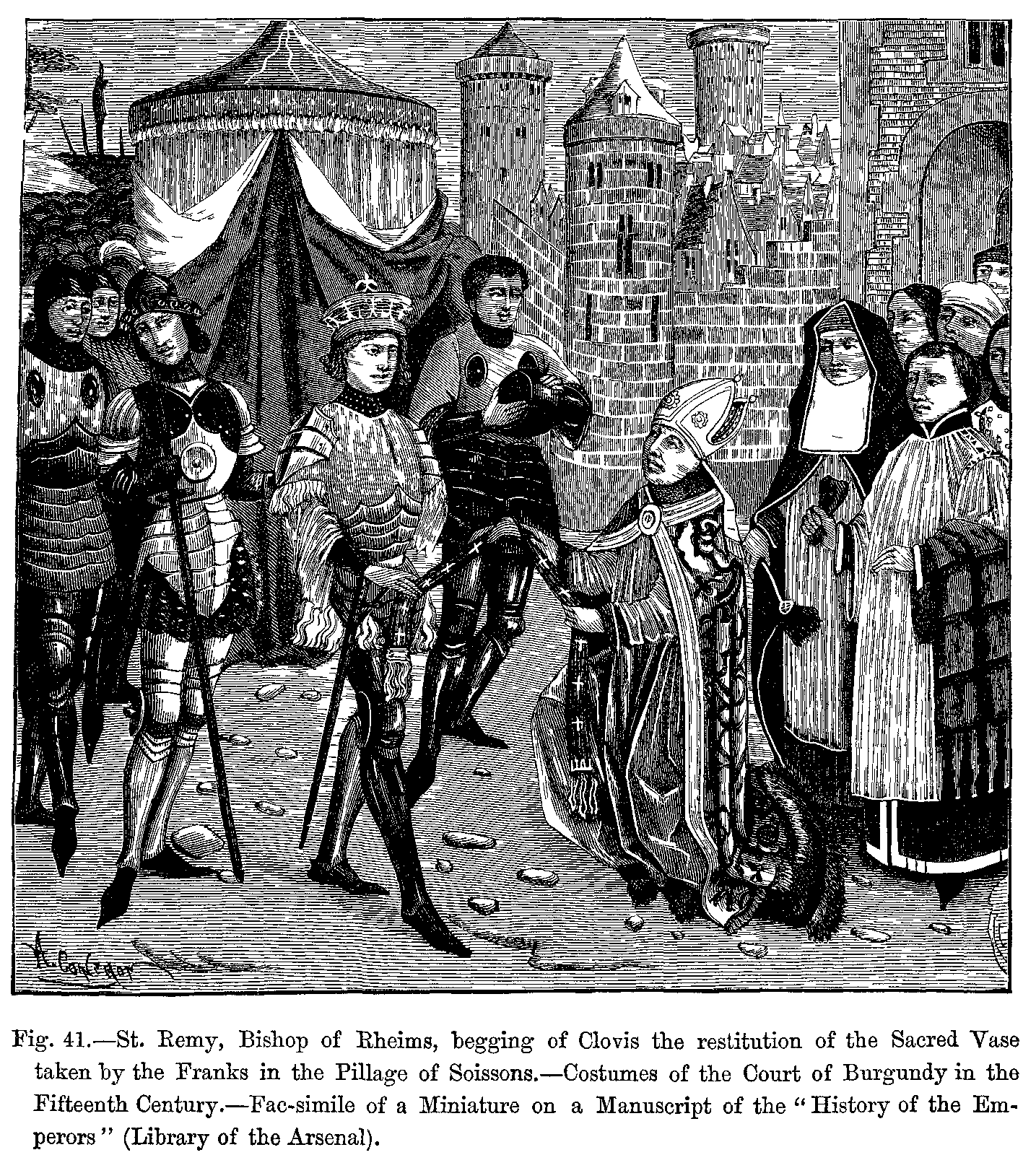

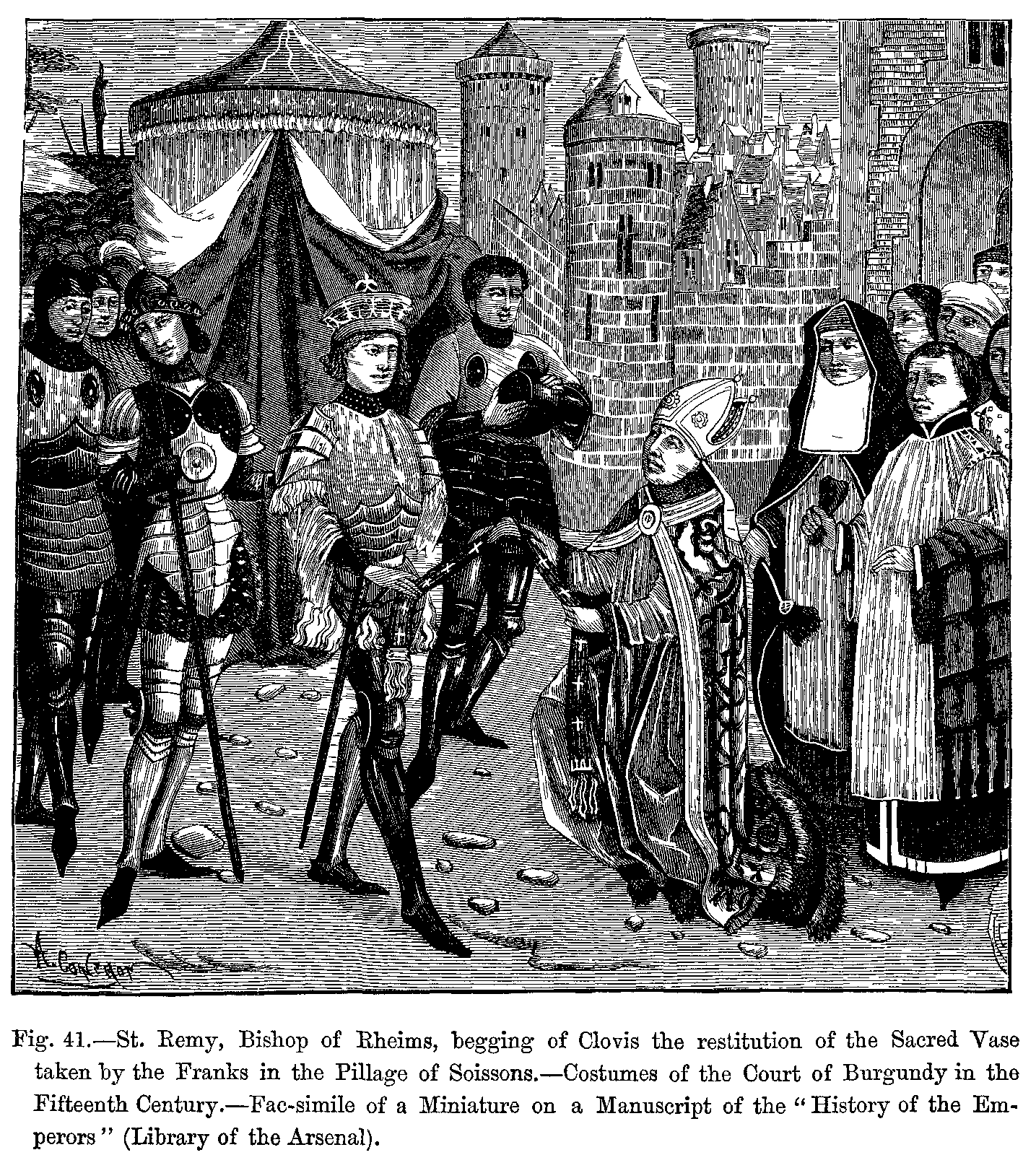

Before the Roman conquest of northern  In 496—ten years after Clovis, King of the Salian Franks, won his victory at Soissons (486)— Remigius, the bishop of Reims, baptized him using the oil of the sacred phial–purportedly brought from heaven by a dove for the baptism of Clovis and subsequently preserved in the Abbey of Saint-Remi. For centuries the events at the crowning of Clovis I became a symbol used by the monarchy to claim the divine right to rule.

Meetings of Pope Stephen II (752–757) with

In 496—ten years after Clovis, King of the Salian Franks, won his victory at Soissons (486)— Remigius, the bishop of Reims, baptized him using the oil of the sacred phial–purportedly brought from heaven by a dove for the baptism of Clovis and subsequently preserved in the Abbey of Saint-Remi. For centuries the events at the crowning of Clovis I became a symbol used by the monarchy to claim the divine right to rule.

Meetings of Pope Stephen II (752–757) with  The archbishops held the important prerogative of the consecration of the kings of France – a privilege which they exercised (except in a few cases) from the time of Philippe II Augustus (anointed 1179, reigned 1180–1223) to that of

The archbishops held the important prerogative of the consecration of the kings of France – a privilege which they exercised (except in a few cases) from the time of Philippe II Augustus (anointed 1179, reigned 1180–1223) to that of  Louis VII granted the city a communal charter in 1139. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) ceded it to the English, who had made a futile attempt to take it by siege in 1360; French patriots expelled them on the approach of

Louis VII granted the city a communal charter in 1139. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) ceded it to the English, who had made a futile attempt to take it by siege in 1360; French patriots expelled them on the approach of  On 30 October 1908, Henri Farman made the first cross-country flight from Châlons to Reims. In August 1909 Reims hosted the first international aviation meet, the '' Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne''. Major aviation personages such as

On 30 October 1908, Henri Farman made the first cross-country flight from Châlons to Reims. In August 1909 Reims hosted the first international aviation meet, the '' Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne''. Major aviation personages such as

File:Reims OSM 01.png, alt=, Map of Rheims

File:Tombeau de Jovin Musée Saint-Remi 90208 01.jpg, alt=, Sarcophagus of Jovinus ( Musée Saint-Remi)

File:Clovis crop.jpg, alt=, Master of Saint Giles, ''The Baptism of Clovis'' (detail), ( National Gallery of Art)

File:Douai-Rheims New Testament (1582).jpg, alt=, The New Testament of the Douay–Rheims Bible was printed in Reims in 1582.

File:Statue de Louis XV Place Royale Reims 03.jpg, alt=, Monument to King Louis XV of France, at the center of Place Royale

File:(Top) - German officers sign unconditional surrender in Reims, France. (Bottom) - Allied force leaders at the signing. - NARA - 195337.jpg, alt=, German surrender of 7 May 1945 in Reims. Top: German officers sign unconditional surrender in Reims. Bottom: Allied force leaders at the signing.

Restaurants and bars are concentrated around Place Drouet d'Erlon in the city centre.

Reims, along with Épernay and Ay, functions as one of the centres of champagne production. Many of the largest champagne-producing houses, known as ''les grandes marques'', have their headquarters in Reims, and most open for tasting and tours. Champagne ages in the many caves and tunnels under Reims, which form a sort of maze below the city. Carved from

Restaurants and bars are concentrated around Place Drouet d'Erlon in the city centre.

Reims, along with Épernay and Ay, functions as one of the centres of champagne production. Many of the largest champagne-producing houses, known as ''les grandes marques'', have their headquarters in Reims, and most open for tasting and tours. Champagne ages in the many caves and tunnels under Reims, which form a sort of maze below the city. Carved from

Between 1925 and 1969, Reims hosted the '' Grand Prix de la Marne'' automobile race at the circuit of Reims-Gueux. The French Grand Prix took place here 14 times between 1938 and 1966.

, the football club '' Stade Reims'', based in the city, competed in the

Between 1925 and 1969, Reims hosted the '' Grand Prix de la Marne'' automobile race at the circuit of Reims-Gueux. The French Grand Prix took place here 14 times between 1938 and 1966.

, the football club '' Stade Reims'', based in the city, competed in the

Tourist office (L'Office de Tourisme de Reims) website

{{Authority control Champagne (province) Cities in France Communes of Marne (department) Gallia Belgica Remi Subprefectures in France

Aisne

Aisne ( , ; ; ) is a French departments of France, department in the Hauts-de-France region of northern France. It is named after the river Aisne (river), Aisne. In 2020, it had a population of 529,374.

Geography

The department borders No ...

.

Founded by the Gauls

The Gauls (; , ''Galátai'') were a group of Celts, Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age Europe, Iron Age and the Roman Gaul, Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). Th ...

, Reims became a major city in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. Reims later played a prominent ceremonial role in French monarchical history as the traditional site of the coronation of the kings of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

. The royal anointing

Anointing is the ritual, ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body. By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, ...

was performed at the Cathedral of Reims

Notre-Dame de Reims (; ; meaning "Our Lady of Reims"), known in English as Reims Cathedral, is a Catholic Church, Catholic cathedral in the Reims, French city of the same name, the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Reims, Archdiocese of R ...

, which housed the Holy Ampulla of chrism

Chrism, also called ''myrrh'', ''myron'', ''holy anointing oil'', and consecrated oil, is a consecrated oil used in the Catholic Church, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox, Assyrian C ...

allegedly brought by a white dove at the baptism of Frankish king Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

in 496. For this reason, Reims is often referred to in French as ("the Coronation City").

Reims is recognized for the diversity of its heritage, ranging from Romanesque to Art-déco. Reims Cathedral, the adjacent Palace of Tau, and the Abbey of Saint-Remi were listed together as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1991 because of their outstanding Romanesque and Gothic architecture and their historical importance to the French monarchy. Reims also lies on the northern edge of the Champagne wine region and is linked to its production and export.

History

Before the Roman conquest of northern

Before the Roman conquest of northern Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

, Reims had served as the Remi tribe's capital, founded . In the course of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

's conquest of Gaul

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, and Switzerland). Gallic, Germanic, and Brittonic tribes fought to defend their homelands ag ...

(58–51 BC), the Remi allied themselves with the Romans, and by their fidelity throughout the various Gallic insurrections secured the special favour of the imperial power. At its height in Roman times the city had a population in the range of 30,000–50,000 or perhaps up to 100,000.

Reims was first called in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, which is hypothesized to derive from a Gaulish

Gaulish is an extinct Celtic languages, Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, ...

name meaning "Door of Cortoro-". The city later took its name from the Remi tribe ( or ). The modern French name is derived from the accusative case

In grammar, the accusative case ( abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: "me", "him", "he ...

of the latter, .

Christianity had become established in the city by 260, at which period Saint Sixtus of Reims founded the Diocese of Reims (which would be elevated to an archdiocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

around 750). The consul Jovinus, an influential supporter of the new faith, repelled the Alamanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River during the first millennium. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Roman emperor Caracalla of 213 CE, the Alemanni c ...

who invaded Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

in 336, but the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

captured the city in 406 and slew Bishop Nicasius; in 451 Attila the Hun put Reims to fire and sword.

In 496—ten years after Clovis, King of the Salian Franks, won his victory at Soissons (486)— Remigius, the bishop of Reims, baptized him using the oil of the sacred phial–purportedly brought from heaven by a dove for the baptism of Clovis and subsequently preserved in the Abbey of Saint-Remi. For centuries the events at the crowning of Clovis I became a symbol used by the monarchy to claim the divine right to rule.

Meetings of Pope Stephen II (752–757) with

In 496—ten years after Clovis, King of the Salian Franks, won his victory at Soissons (486)— Remigius, the bishop of Reims, baptized him using the oil of the sacred phial–purportedly brought from heaven by a dove for the baptism of Clovis and subsequently preserved in the Abbey of Saint-Remi. For centuries the events at the crowning of Clovis I became a symbol used by the monarchy to claim the divine right to rule.

Meetings of Pope Stephen II (752–757) with Pepin the Short

the Short (; ; ; – 24 September 768), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian dynasty, Carolingian to become king.

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude of H ...

, and of Pope Leo III (795–816) with Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

(died 814), took place at Reims; here Pope Stephen IV

Pope Stephen IV (; died 24 January 817) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from June 816 to his death on 24 January 817.

crowned Louis the Debonnaire in 816. King Louis IV gave the city and countship of Reims to the archbishop Artaldus in 940. King Louis VII (reigned 1137–1180) gave the title of duke and peer to William of Champagne, archbishop from 1176 to 1202, and the archbishops of Reims took precedence over the other ecclesiastical peers of the realm.

By the 10th century, Reims had become a centre of intellectual culture. Archbishop Adalberon (in office 969 to 988), seconded by the monk Gerbert (afterwards (from 999 to 1003) Pope Silvester II), founded schools which taught the classical "liberal arts

Liberal arts education () is a traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''skill, art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the fine arts. ''Liberal arts education'' can refe ...

". (Adalberon also played a leading role in the dynastic revolution which elevated the Capetian dynasty in the place of the Carolingians.)

The archbishops held the important prerogative of the consecration of the kings of France – a privilege which they exercised (except in a few cases) from the time of Philippe II Augustus (anointed 1179, reigned 1180–1223) to that of

The archbishops held the important prerogative of the consecration of the kings of France – a privilege which they exercised (except in a few cases) from the time of Philippe II Augustus (anointed 1179, reigned 1180–1223) to that of Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

(anointed 1825). The Palace of Tau, built between 1498 and 1509 and partly rebuilt in 1675, would later serve as the Archbishop's palace and as the residence of the kings of France on the occasion of their coronations, with royal banquets taking place in the ''Salle du Tau''.

Louis VII granted the city a communal charter in 1139. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) ceded it to the English, who had made a futile attempt to take it by siege in 1360; French patriots expelled them on the approach of

Louis VII granted the city a communal charter in 1139. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) ceded it to the English, who had made a futile attempt to take it by siege in 1360; French patriots expelled them on the approach of Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc ( ; ; – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the Coronation of the French monarch, coronation of Charles VII o ...

, who in 1429 had Charles VII consecrated in the cathedral. Louis XI

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the ...

cruelly suppressed a revolt at Reims, caused in 1461 by the salt tax

A salt tax refers to the direct taxation of salt, usually levied proportionately to the volume of salt purchased. The taxation of salt dates as far back as 300 BC, as salt has been a valuable good used for gifts and religious offerings since 605 ...

.

During the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

the city sided with the Catholic League (1585), but submitted to King Henri IV after the battle of Ivry

The Battle of Ivry was fought on 14 March 1590, during the French Wars of Religion. The battle was a decisive victory for Henry IV of France, leading French royal and English forces against the Catholic League by the Duc de Mayenne and Spani ...

(1590). At about the same time, the English College had been "at Reims for some years."

The city was stricken with plague in 1635, and again in 1668, followed by an epidemic of typhus in 1693–1694. The construction of the dates back to the same century.

The Place Royale was built in the 18th century. Some of the 1792 September Massacres took place in Reims.

In the invasions of the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition () (December 1812 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation (), a coalition of Austrian Empire, Austria, Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia, Russian Empire, Russia, History of Spain (1808– ...

in 1814, anti-Napoleonic allied armies captured and re-captured Reims. "In 1852, the Eastern Railways completed the Paris-Strasbourg main line with branch lines to Reims and Metz." In 1870–1871, during the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, the victorious Germans made it the seat of a governor-general and impoverished it with heavy requisitions. In 1874 the construction of a chain of detached fort

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from La ...

s started in the vicinity, the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

having selected Reims as one of the chief defences of the northern approaches to Paris. In the meantime, British inventor and manufacturer Isaac Holden had opened plants at Reims and Croix

Croix (French for "cross") may refer to:

Belgium

* Croix-lez-Rouveroy, a village in municipality of Estinnes in the province of Hainaut

France

* Croix, Nord, in the Nord department

* Croix, Territoire de Belfort, in the Territoire de Belfort depa ...

, which "by the 1870s ..were producing almost 12 million kilograms of combed wool a year ..and accounted for 27 percent of all the wool consumed by French industry."

On 30 October 1908, Henri Farman made the first cross-country flight from Châlons to Reims. In August 1909 Reims hosted the first international aviation meet, the '' Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne''. Major aviation personages such as

On 30 October 1908, Henri Farman made the first cross-country flight from Châlons to Reims. In August 1909 Reims hosted the first international aviation meet, the '' Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne''. Major aviation personages such as Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

, Louis Blériot and Louis Paulhan participated.

Hostilities in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

greatly damaged the city. German bombardment and a subsequent fire in 1914 did severe damage to the cathedral. The ruined cathedral became one of the central images of anti-German propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

produced in France during the war, which presented it, along with the ruins of the Ypres Cloth Hall and the University Library in Louvain, as evidence that German aggression targeted cultural landmarks of European civilization. Since the end of World War I, an international effort to restore the cathedral from the ruins has continued.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the city suffered additional damage. On the morning of 7 May 1945, at 2:41, General Eisenhower and the Allies received the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

in Reims. General Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; born Alfred Josef Baumgärtler; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German Wehrmacht Heer, Army ''Generaloberst'' (the rank was equal to a four-star full general) and War crime, war criminal, who served as th ...

, German Chief-of-Staff, signed the surrender at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force ( SHAEF) as the representative for German President Karl Dönitz.

The British statesman Leslie Hore-Belisha died of a cerebral haemorrhage while making a speech at the in February 1957.

Administration

Reims functions as asubprefecture

A subprefecture is an administrative division of a country that is below prefecture or province.

Albania

There are twelve Counties of Albania, Albanian counties or prefectures, each of which is divided into several Districts of Albania, district ...

of the department of Marne, in the administrative region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

of Grand Est

Grand Est (; ) is an Regions of France, administrative region in northeastern France. It superseded three former administrative regions, Alsace, Champagne-Ardenne and Lorraine, on 1 January 2016 under the provisional name of Alsace-Champagne-A ...

. Although Reims is by far the largest commune in its department, Châlons-en-Champagne

Châlons-en-Champagne () is a city in the Grand Est region of France. It is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Marne (department), Marne, despite being only a quarter the size of the city of Reims.

Formerly called Châlons ...

is the prefecture

A prefecture (from the Latin word, "''praefectura"'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain inter ...

. Reims co-operates with 142 other communes in the ''Communauté urbaine

(; French for "urban community") is the second most integrated form of intercommunality in France, after the ''Metropolis'' (). A is composed of a city ( commune) and its independent suburbs (independent communes).

The first communautés urba ...

du Grand Reims''.

Demographics

Economy

Rue de Vesle is the main commercial street (continued under other names), traversing the city from southwest to northeast through the Place Royale. The economy of Reims is driven by the wine and Champagne industries and innovation in the bio-economic field.Architecture

Reims Cathedral is an example of French Gothic architecture. The Basilica of Saint-Remi, founded in the 11th century "over the chapel of St. Christophe where St. Remi was buried", is "the largest Romanesque church in northern France, though with later additions." The Church of Saint-Jacques dates from the 13th to the 16th centuries. A few blocks from the cathedral, it stands in a neighbourhood of shopping and restaurants. The churches of Saint-Maurice (partly rebuilt in 1867), Saint-André, and Saint-Thomas (erected from 1847 to 1853, under the patronage of Cardinal Gousset, now buried within its walls) also draw tourists. The Protestant Church of Reims, built in 1921–1923 over designs by Charles Letrosne, is an example of flamboyant neo-Gothic architecture. The Hôtel de Ville, erected in the 17th century and enlarged in the 19th, features apediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

with an equestrian statue of Louis XIII (reigned 1610 to 1643).

Narcisse Brunette was the architect of the city for nearly 50 years in the 19th century. He designed the Reims Manège and Circus, which "combines stone and brick in a fairly sober classical composition."

Examples of Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French (), is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design that first Art Deco in Paris, appeared in Paris in the 1910s just before World War I and flourished in the United States and Europe during the 1920 ...

in Reims include the Carnegie library.

The Foujita Chapel, built in 1965–1966 over designs and with frescos by Japanese–French artist Tsuguharu Foujita, has been listed as a '' monument historique'' since 1992.

Culture

Reims was a candidate in the bid to become theEuropean Capital of Culture

A European Capital of Culture is a city designated by the European Union (EU) for a period of one calendar year during which it organises a series of cultural events with a strong pan-European dimension. Being a European Capital of Culture can ...

in 2028, however was eliminated in the preselection round.

Museums

The Palace of Tau contains such exhibits as statues formerly displayed by the cathedral, treasures of the cathedral from past centuries, and royal attire from coronations of French kings. The Musée Saint-Remi, formerly the Abbey of Saint-Remi, contains tapestries from the 16th century donated by the archbishop Robert de Lenoncourt (uncle of the cardinal of the same name), marble capitals from the fourth century AD, furniture, jewellery, pottery, weapons and glasswork from the sixth to eighth centuries, medieval sculpture, the façade of the 13th-century musicians' House, remnants from an earlier abbey building, and also exhibits of Gallo-Roman arts and crafts and a room of pottery, jewellery and weapons from Gallic civilization, as well as an exhibit of items from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic periods. Another section of the museum features a permanent military exhibition. The Automobile Museum Reims-Champagne, established in 1985 by Philippe Charbonneaux, houses a collection of automobiles dating from 1903 to the present day. The museum has five collections: automobiles, motorcycles and two-wheelers, pedal cars, miniature toys, and enamel plaques. The Museum of Fine Arts is housed in the former Abbey of Saint-Denis. Part of the former Collège des Jésuites has also become a contemporary art gallery: the FRAC Champagne-Ardenne. The Museum of the Surrender is the building in which on 7 May 1945, General Eisenhower and the Allies received the unconditional surrender of the GermanWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

.

Theaters

Venues include the Reims Opera House, built in 1873 and renovated in 1931–1932, and the Reims Manège and Circus, dating from 1865 and 1867. The Comédie de Reims was inaugurated in 1966.Libraries

Libraries in Reims include a Carnegie library which was built in the 1920s.Festivals and events

At the beginning of the year, the FARaway - Festival des Arts à Reims is a two-week event of music, dance, theatre, exhibitions, and installations at various cultural venues around the city. Every year in June, the ''Fêtes Johanniques'' commemorate the entrance of Joan of Arc into Reims in 1429 and the coronation of Charles VII of France in the cathedral. In August and September there are regular evening light shows called Regalia projected onto the Reims Cathedral. It has a duration of 15 minutes and is free of charge. Regalia is an open-air multimedia show telling the story of the French coronations in a dramatic and whimsical fashion. Pets are welcome. AChristmas market

A Christmas market is a street market associated with the celebration of Christmas during the four weeks of Advent. These markets originated in Germany, but are now held in many countries. Some in the U.S. have Phono-semantic matching, adapted ...

was held on the parvis of Reims Cathedral (Place du Cardinal-Luçon). It has since been moved in front of the Reims train station. In takes place in the month before Christmas, in 2023 this will be November 24th until December 24th. The Christmas market in Reims is the 3rd largest Christmas market in France. There are 150 different stalls each with various regional crafts, gifts, foods and specialities. This includes a famous poutine stand. The market last year was open on Mondays from 2pm to 8pm, Tuesday to Thursday from 10:30am to 10pm, Friday from 10:30am to 10pm, Saturday from 10am to 10pm, and Sundays from 10pm to 8pm. Access to the Christmas market is free and it is accessible to people with reduced mobility. Dogs are welcome if they are on a leash. Close by, there is a large traditional Christmas tree.

Wine and food

Restaurants and bars are concentrated around Place Drouet d'Erlon in the city centre.

Reims, along with Épernay and Ay, functions as one of the centres of champagne production. Many of the largest champagne-producing houses, known as ''les grandes marques'', have their headquarters in Reims, and most open for tasting and tours. Champagne ages in the many caves and tunnels under Reims, which form a sort of maze below the city. Carved from

Restaurants and bars are concentrated around Place Drouet d'Erlon in the city centre.

Reims, along with Épernay and Ay, functions as one of the centres of champagne production. Many of the largest champagne-producing houses, known as ''les grandes marques'', have their headquarters in Reims, and most open for tasting and tours. Champagne ages in the many caves and tunnels under Reims, which form a sort of maze below the city. Carved from chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

, some of these passages date back to Roman times.

The '' biscuit rose de Reims'' is a biscuit frequently associated with Champagne wine. Reims was long renown for its '' pain d'épices'' and ''nonnette''.

Sports

Between 1925 and 1969, Reims hosted the '' Grand Prix de la Marne'' automobile race at the circuit of Reims-Gueux. The French Grand Prix took place here 14 times between 1938 and 1966.

, the football club '' Stade Reims'', based in the city, competed in the

Between 1925 and 1969, Reims hosted the '' Grand Prix de la Marne'' automobile race at the circuit of Reims-Gueux. The French Grand Prix took place here 14 times between 1938 and 1966.

, the football club '' Stade Reims'', based in the city, competed in the Ligue 1

Ligue 1 (; ), officially known as Ligue 1 McDonald's France, McDonald's for sponsorship reasons, is a professional association football league in France and the highest level of the French football league system. Administered by the Ligue de ...

, the highest tier of French football. ''Stade Reims'' became the outstanding team of France in the 1950s and early 1960s and reached the final of the European Cup of Champions twice in that era.

In October 2018, the city hosted the second Teqball World Cup.

The city has hosted the Reims Marathon since 1984.

Transport

Reims is served by two main railway stations: Gare de Reims in the city centre, the hub for regional transport, and the new Gare de Champagne-Ardenne TGV southwest of the city with high-speed rail connections to Paris, Metz, Nancy and Strasbourg. There are two other railway stations for local services in the southern suburbs: Franchet d'Esperey and Reims-Maison-Blanche. The motorways A4 (Paris-Strasbourg), A26 (Calais-Langres) and A34 intersect near Reims.Public transport within the city consists of buses and a tramway, the latter opened in 2011. There is also a bikeshare program, Zébullo. The Canal de l'Aisne à la Marne is a waterway. There is also an airport, Reims – Prunay Aerodrome, but it had, as of 2020, no commercial airline flights.Parks and gardens

Among the parks and gardens of Reims are the Parc de Champagne, where a Monument to the Heroes of the Black Army is located. Next to the main train station, there is the Hautes Promenades, which is a park equipped with leisure facilities such as swings, hammocks, a carousel, in-ground trampolines, and a water park. Smaller gardens and parks are also peppered throughout Reims, such as Jardin Le Vergeur, Parc Léo-Lagrange, and the Parc Saint-Remi which next to the Basilica of Saint-Remi.Higher education

The Institut d'Etudes politiques de Paris, the leading French university in social and political sciences, also known as SciencesPo Paris, opened a new campus in the former in 2010. It hosts both the Europe-Africa and Europe-America Program with more than 1,500 students in the respective programs. Aside from its Jesuit architecture, the campus also features the oldest grape vines in France, which are harvested every year by the City of Reims and are not at the disposal of students or visitors. In 2012 the first Reims Model United Nations was launched, which gathered 200 international students from all the Sciences Po campuses. Daniel Rondeau, the ambassador of France toUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

and a French writer, is the patron of the event.

The URCA (Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne) was founded in 1548. This multidisciplinary university develops innovative, fundamental, and applied research. It provides more than 18,000 students in Reims (22,000 in Champagne-Ardenne) with a wide initial undergraduate studies program which corresponds to society's needs in all domains of the knowledge. The university also accompanies independent or company-backed students in continuing professional development training.

NEOMA Business School (former Reims Management School) is also one of the main schools in Reims. The Advanced Business School of Reims was created in 1928. It took the name Reims Management School in 2000.

Notable residents

Those born in Reims include: * Adolphe d'Archiac (1802–1868), geologist and paleontologist *Jean Baudrillard

Jean Baudrillard (, ; ; – 6 March 2007) was a French sociology, sociologist and philosopher with an interest in cultural studies. He is best known for his analyses of media, contemporary culture, and technological communication, as well as hi ...

(1929–2007), cultural theorist and philosopher

* (born 1974), comedian

* Nicolas Bergier (1567–1623), scholar of Roman roads

Roman roads ( ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Em ...

* Brodinski (born 1987), musical artist and DJ

* Roger Caillois

Roger Caillois (; 3 March 1913 – 21 December 1978) was a French intellectual and prolific writer whose original work brought together literary criticism, sociology, poetry, ludology and philosophy by focusing on very diverse subjects such as ...

(1913–1978), intellectual

* Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), Minister of Finance from 1665 to 1683 under the reign of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

* (1817–1902), librarian of Reims, fervent republican

* Anne-Sophie Da Costa (1982), boxe

* Jean Del Val (1891–1975), actor

* Rose Delaunay (born 1857), opera singer

* Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Count d'Erlon (1765–1844), marshal of France

Marshal of France (, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to General officer, generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1793–1804) ...

and soldier in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's army

* Hugo Ekitike (born 2002), professional footballer

* Paul Fort (1872–1960), poet

* Nicolas Eugène Géruzez (1799–1865), critic

* Pauline Ferrand-Prévot (born 1992), world champion cyclist

* Nicolas de Grigny (1672–1703), organist and composer

* Maurice Halbwachs (1877–1945), philosopher and sociologist

* Kyan Khojandi (born 1982), comedian, actor and screenwriter

* Jean Lévesque de Burigny (1692–1785), historian

* Marie-Claire Jamet (born 1933), classical harpist

* Guillaume de Machaut

Guillaume de Machaut (, ; also Machau and Machault; – April 1377) was a French composer and poet who was the central figure of the style in late medieval music. His dominance of the genre is such that modern musicologists use his death to ...

(1300–1377), composer and poet (Machaut was most likely born in Reims or nearby; he spent most of his adult life there)

* Henri Marteau (1874–1934), violinist and composer

* Merolilan of Rheims, Irish cleric

* Olivier Métra (1830–1889), composer, conductor

* Maurice Pézard (1876–1923), archaeologist and assyriologist

* Robert Pires (born 1973), World Cup winner, footballer for Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

and for Villarreal CF

* Patrick Poivre d'Arvor (born 1947), television journalist and writer

* Jean-Baptiste de la Salle (1651–1719), Catholic saint, teacher and educational reformer

* Jules de Saint-Pol (1810–1855), general

* Émile Senart (1847–1928), indologist

* Adeline Wuillème (born 1975), foil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ma ...

fencer

* Yuksek (born 1977), electronic music producer, remixer, singer and DJ

Climate

Reims has anoceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen climate classification, Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

''Cfb''), influenced by its inland position. This renders that although the maritime influence moderates averages, it nevertheless is prone to hot and cold extremes in certain instances. Reims has a relatively gloomy climate due to the said maritime influence and the dominance of low-pressure systems for much of the year. In spite of this, the amount of precipitation is fairly limited.

Twin towns – sister cities

Reims is twinned with: *Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Italy (1954)

* Brazzaville

Brazzaville () is the capital (political), capital and largest city of the Republic of the Congo. Administratively, it is a Departments of the Republic of the Congo, department and a Communes of the Republic of the Congo, commune. Constituting t ...

, Congo (1961)

* Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

, England, United Kingdom (1962)

* Salzburg

Salzburg is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020 its population was 156,852. The city lies on the Salzach, Salzach River, near the border with Germany and at the foot of the Austrian Alps, Alps moun ...

, Austria (1964)

* Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

, Germany (1967)

* Arlington County, United States (2004)

* Kutná Hora, Czech Republic (2008)

* Nagoya

is the largest city in the Chūbu region of Japan. It is the list of cities in Japan, fourth-most populous city in Japan, with a population of 2.3million in 2020, and the principal city of the Chūkyō metropolitan area, which is the List of ...

, Japan (2018)

See also

*Archbishop of Reims

The Archdiocese of Reims or Rheims (; French language, French: ''Archidiocèse de Reims'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastic territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. Erected as a diocese around 250 by Sixtus of Reims, the diocese w ...

* Battle of Reims

* Biscuit rose de Reims

* Champagne (province)

Champagne () was a province in the northeast of the Kingdom of France, now best known as the Champagne wine region for the sparkling white wine that bears its name in modern-day France. The County of Champagne, descended from the early medie ...

* Champagne Riots

* Reims Aviation

Notes

References

Bibliography

External links

*Tourist office (L'Office de Tourisme de Reims) website

{{Authority control Champagne (province) Cities in France Communes of Marne (department) Gallia Belgica Remi Subprefectures in France