Reichswehr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the

A similarly worded law on the formation of a provisional navy dated 16 April 1919 authorized it to “secure the German coasts, enable safe maritime traffic by clearing mines, acting as maritime police and otherwise assisting merchant shipping, ensure the undisturbed exercise of fishing, enforce the orders of the Reich government in conjunction with the Reichswehr, and maintain peace and order." The strength of the navy was to be 20,000 men.

From 1 October 1919 to 1 April 1920, the forces of the Provisional Reich Army were moved into the 400,000-strong ‘Transitional Army’ consisting of 20 brigades. At the same time, the old army’s units and duties were eliminated. After falling to 150,000 men in October 1920, the brigades were replaced by regiments, and the final army strength of 100,000 was reached by 1 January 1921. The Reichswehr was officially formed on that date, with the Defense Law of 23 March 1921 regulating the details. The soldiers’ oath was sworn to the Weimar Constitution.

A similarly worded law on the formation of a provisional navy dated 16 April 1919 authorized it to “secure the German coasts, enable safe maritime traffic by clearing mines, acting as maritime police and otherwise assisting merchant shipping, ensure the undisturbed exercise of fishing, enforce the orders of the Reich government in conjunction with the Reichswehr, and maintain peace and order." The strength of the navy was to be 20,000 men.

From 1 October 1919 to 1 April 1920, the forces of the Provisional Reich Army were moved into the 400,000-strong ‘Transitional Army’ consisting of 20 brigades. At the same time, the old army’s units and duties were eliminated. After falling to 150,000 men in October 1920, the brigades were replaced by regiments, and the final army strength of 100,000 was reached by 1 January 1921. The Reichswehr was officially formed on that date, with the Defense Law of 23 March 1921 regulating the details. The soldiers’ oath was sworn to the Weimar Constitution.

Two Reich Presidents held office during the Weimar Republic:

Two Reich Presidents held office during the Weimar Republic:

In March 1920 Germany’s political leadership did not use the Reichswehr against the

In March 1920 Germany’s political leadership did not use the Reichswehr against the

Seeckt was succeeded by

Seeckt was succeeded by

In 1931 and 1932, a series of actions by the Reichswehr and its leadership showed its increasing power and drift towards the Nazis:

* When the Harzburg Front, an anti-democratic alliance that included the Nazi Party, was formed in 1931, high-ranking members of the Reichswehr were present.

* In 1932 Defense Minister Groener, under pressure from several German states, outlawed the Nazi

In 1931 and 1932, a series of actions by the Reichswehr and its leadership showed its increasing power and drift towards the Nazis:

* When the Harzburg Front, an anti-democratic alliance that included the Nazi Party, was formed in 1931, high-ranking members of the Reichswehr were present.

* In 1932 Defense Minister Groener, under pressure from several German states, outlawed the Nazi

During 1933 and 1934 the Reichswehr began a secret program of expansion. In December 1933 the army staff decided to increase the active strength to 300,000 men in 21 divisions. On 1 April 1934, between 50,000 and 60,000 new recruits entered the force and were assigned to special training battalions. The original seven infantry divisions of the Reichswehr were expanded to 21, with military district headquarters increased to the size of a corps headquarters on 1 October 1934. These divisions used cover names to hide their divisional size, but during October 1935 they were dropped. Also during October 1934, the officers who had been forced to retire in 1919 were recalled. Those who were no longer fit for combat were assigned to administrative positions, thus releasing fit officers for front-line duties.

On 2 August 1934, the day Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died, Reichswehr Minister

During 1933 and 1934 the Reichswehr began a secret program of expansion. In December 1933 the army staff decided to increase the active strength to 300,000 men in 21 divisions. On 1 April 1934, between 50,000 and 60,000 new recruits entered the force and were assigned to special training battalions. The original seven infantry divisions of the Reichswehr were expanded to 21, with military district headquarters increased to the size of a corps headquarters on 1 October 1934. These divisions used cover names to hide their divisional size, but during October 1935 they were dropped. Also during October 1934, the officers who had been forced to retire in 1919 were recalled. Those who were no longer fit for combat were assigned to administrative positions, thus releasing fit officers for front-line duties.

On 2 August 1934, the day Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died, Reichswehr Minister

Axis History Factbook — Reichswehr

Feldgrau's overview of the Reichswehr

The Archives of technical Manuals 1900–1945 (includes the Reichswehr-regulations)

{{Authority control Military of the Weimar Republic Military history of Germany

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

and the first years of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. After Germany was defeated in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped into a peacetime army. From it a provisional Reichswehr was formed in March 1919. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, the rebuilt German army was subject to severe limitations in size and armament. The official formation of the Reichswehr took place on 1 January 1921 after the limitations had been met. The German armed forces kept the name 'Reichswehr' until Adolf Hitler's 1935 proclamation of the "restoration of military sovereignty", at which point it became part of the new .

Although ostensibly apolitical, the Reichswehr acted as a state within a state, and its leadership was an important political power factor in the Weimar Republic. The Reichswehr sometimes supported the democratic government, as it did in the Ebert-Groener Pact when it pledged its loyalty to the Republic, and sometimes backed anti-democratic forces through such means as the Black Reichswehr

Black Reichswehr (german: Schwarze Reichswehr) was the name for the extra-legal paramilitary formations promoted by the German Reichswehr army during the time of the Weimar Republic; it was raised despite restrictions imposed by the Versailles Tre ...

, the illegal paramilitary groups it sponsored in contravention of the Versailles Treaty. The Reichswehr saw itself as a cadre army that would preserve the expertise of the old imperial military and form the basis for German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germ ...

.

Structure of the Reichswehr

Arms limitations under the Treaty of Versailles

In Part V of the 1919 Versailles Peace Treaty, Germany had obligated itself to limit the size and armaments of its military forces so that they could be used only as border protection and for the maintenance of order within Germany. In accordance with the treaty's provisions, personnel strength was limited to a professional army of 100,000 men plus a 15,000-man navy. The establishment of a general staff was prohibited. Heavy weapons above defined calibers, armored vehicles, submarines and large warships were prohibited, as was any type of air force. The regulations were overseen by theMilitary Inter-Allied Commission of Control

The term Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control was used in a series of peace treaties concluded after the First World War (1914–1918) between different countries. Each of these treaties was concluded between the Principal Allied and A ...

until 1927.

Conscription into the German army had traditionally been for a period of 1 to 3 years. After they had completed their terms of service, the discharged soldiers created a large pool of trained reserves. The Versailles Treaty fixed the term of service for Reichswehr officers at 25 years and for all others at 12 in order to prevent such a buildup of reservists.

Founding

On 9 November 1918, at the beginning the German Revolution that led to the collapse of theGerman Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and the flight of Emperor Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empi ...

, a republic was proclaimed from Berlin. The next day, German Chancellor

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

and General Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener (; 22 November 1867 – 3 May 1939) was a German general and politician. His organisational and logistical abilities resulted in a successful military career before and during World War I.

After a confrontation wi ...

, acting in the name of the Supreme Army Command, concluded the Ebert-Groener Pact. In it Groener assured Ebert of the loyalty of the armed forces, and in return Ebert promised that the government would take prompt action against leftist uprisings, call a national assembly, keep the military command within the professional officer corps and, most importantly, retain the military’s traditional status as ‘state within a state’ – that is, it would continue to be largely independent of the civilian government.

As part of the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

, the new German government agreed to the speedy evacuation of occupied territories. The withdrawal on the western front began on 12 November and by 17 January 1919 the areas on the west bank of the Rhine were free of German military forces. The task was then to gradually disarm the units of the Imperial Army which still numbered several million soldiers. This was done at previously designated demobilization sites, usually the respective home garrisons. For the regiments with garrisons on the west bank of the Rhine, demobilization sites were designated in the interior of the Reich.

The Council of the People's Deputies

The Council of the People's Deputies (, sometimes translated as Council of People's Representatives or Council of People's Commissars) was the name given to the government of the November Revolution in Germany from November 1918 until February 19 ...

– the de facto government of Germany from November 1918 until February 1919 – and the Supreme Army Command intended to transfer the remaining units to a peacetime army following demobilization. On 6 March 1919 the Weimar National Assembly

The Weimar National Assembly (German: ), officially the German National Constitutional Assembly (), was the popularly elected constitutional convention and de facto parliament of Germany from 6 February 1919 to 21 May 1920. As part of its ...

passed the law on the formation of a provisional army to be made up of 43 brigades. It authorized the Reich President

''Reich'' (; ) is a German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word " realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emperor") and ' (li ...

"to dissolve the existing army and to form a provisional Reichswehr which, until the creation of a new armed force to be ordered by Reich law, would protect the borders of the Reich, enforce the orders of the Reich government, and maintain domestic peace and order."

A similarly worded law on the formation of a provisional navy dated 16 April 1919 authorized it to “secure the German coasts, enable safe maritime traffic by clearing mines, acting as maritime police and otherwise assisting merchant shipping, ensure the undisturbed exercise of fishing, enforce the orders of the Reich government in conjunction with the Reichswehr, and maintain peace and order." The strength of the navy was to be 20,000 men.

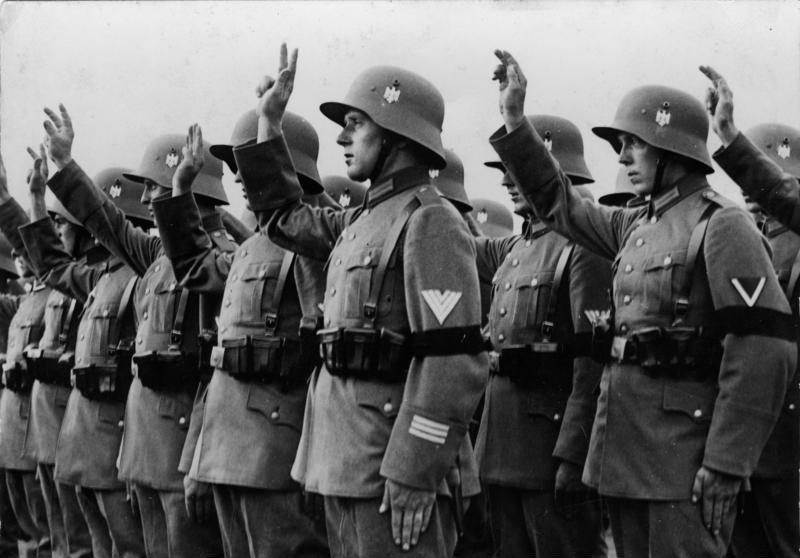

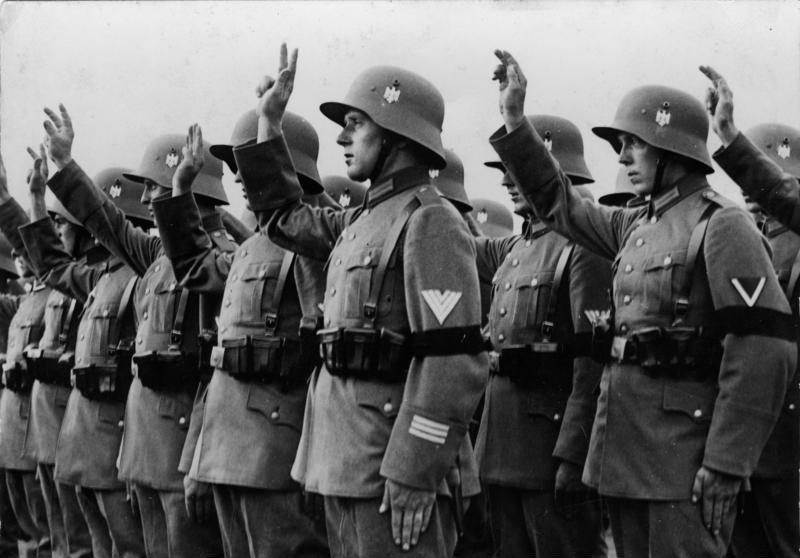

From 1 October 1919 to 1 April 1920, the forces of the Provisional Reich Army were moved into the 400,000-strong ‘Transitional Army’ consisting of 20 brigades. At the same time, the old army’s units and duties were eliminated. After falling to 150,000 men in October 1920, the brigades were replaced by regiments, and the final army strength of 100,000 was reached by 1 January 1921. The Reichswehr was officially formed on that date, with the Defense Law of 23 March 1921 regulating the details. The soldiers’ oath was sworn to the Weimar Constitution.

A similarly worded law on the formation of a provisional navy dated 16 April 1919 authorized it to “secure the German coasts, enable safe maritime traffic by clearing mines, acting as maritime police and otherwise assisting merchant shipping, ensure the undisturbed exercise of fishing, enforce the orders of the Reich government in conjunction with the Reichswehr, and maintain peace and order." The strength of the navy was to be 20,000 men.

From 1 October 1919 to 1 April 1920, the forces of the Provisional Reich Army were moved into the 400,000-strong ‘Transitional Army’ consisting of 20 brigades. At the same time, the old army’s units and duties were eliminated. After falling to 150,000 men in October 1920, the brigades were replaced by regiments, and the final army strength of 100,000 was reached by 1 January 1921. The Reichswehr was officially formed on that date, with the Defense Law of 23 March 1921 regulating the details. The soldiers’ oath was sworn to the Weimar Constitution.

Structure

The Reichswehr was divided into the (army) and the ''Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the ''Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the '' ...

'' (navy). The consisted of seven infantry and three cavalry divisions, with all units renumbered. The Reich’s territory was divided into seven military districts. There were two group commands, No. 1 in Berlin and No. 2 in Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel and the district of the same name and had 201,048 inhabitants in December 2020 ...

. The navy was allowed a limited number of certain types of ships and boats, with no submarines. It was divided into Naval Station Baltic Sea and Naval Station North Sea. Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty, the service period for enlisted men and non-commissioned officers in both the army and the navy was 12 years, with 25 years for officers.

The 1921 Defense Law ended the military sovereignty of the states but left Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

, Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

, and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

with limited independence. Bavaria was special in that Military District VII covered the entire territory of the state with the exception of the Palatinate, and only Bavarians served in the 7th (Bavarian) Division. Until 1924 this unit, as the Bavarian Reichswehr, enjoyed certain rights of autonomy with respect to the Reich government.

Reichswehr commanders

According to the Weimar Constitution, the Reich President had "supreme command over the entire armed forces of the Reich". In general, however, he could act only if there was a countersignature by a member of the government. In terms of authority, this was the Reich Minister of the Armed Forces. Two Reich Presidents held office during the Weimar Republic:

Two Reich Presidents held office during the Weimar Republic: Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

until 1925, followed by Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

. The first Reich Minister of the Armed Forces was Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske (9 July 1868 – 30 November 1946) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (''Reichswehrminister'') of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske has been a cont ...

, who was replaced by Otto Geßler

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a Classical liberalism, liberal German politician during the Weimar Republic. From 1910 until 1914, he was mayor of Regensburg and from 1913 to 1919 mayor of Nuremberg. He ...

after the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

in 1920. Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener (; 22 November 1867 – 3 May 1939) was a German general and politician. His organisational and logistical abilities resulted in a successful military career before and during World War I.

After a confrontation wi ...

took office in 1928, and his deputy Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last chancellor of Germany (before Adolf Hitler) during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by ...

replaced him in 1932. Schleicher continued to hold office on a provisional basis during his two-month chancellorship. Prior to Hitler's appointment as Reich chancellor, Hindenburg unilaterally – not at the chancellor's recommendation as required by the constitution – appointed Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German General Staff officer and the first Minister of War in Adolf Hitler's government. After serving on the Western Front in World War I, Blomberg was appointed chi ...

as Reich Minister of the Armed Forces.

The head of army command was initially Walther Reinhardt

Walther Gustav Reinhardt (; 24 March 1872 in Stuttgart – 8 August 1930 in Berlin) was a German officer who served as the last Prussian Minister of War and the first head of the army command (''Chef der Heeresleitung'') within the newly create ...

. After the Kapp Putsch, Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

took over the post and had both the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

(KPD) and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

banned in 1923. Wilhelm Heye

August Wilhelm Heye (31 January 1869, Fulda – 11 March 1947, Braunlage) was a German officer who rose to the rank of Generaloberst and became head of the Army Command within the Ministry of the Reichswehr in the Weimar Republic. One of his ...

followed him in 1926. Heye was succeeded in 1930 by Kurt Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord, who tendered his resignation on 27 December 1933. He was succeeded by Werner von Fritsch

Thomas Ludwig Werner Freiherr von Fritsch (4 August 1880 – 22 September 1939) was a member of the German High Command. He was Commander-in-Chief of the German Army from February 1934 until February 1938, when he was forced to resign after he ...

.

Social composition

Given the limited size of the army, careful selection of personnel was possible. Experienced leaders came from the ‘Old Army’ of the Empire. In 1925, 24% of the officers were from the former nobility, down from 30% in 1913. This continued the long-term trend of a reduction in the percentage of noble officers. Large parts of the officer corps held a conservative, monarchist worldview and rejected the Weimar Republic. Especially within the former nobility, however, the stance towardsNational Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

was not entirely uncritical.

The Reichswehr leadership and officer corps successfully resisted the democratization of the troops. Preference was given to recruits from the predominantly conservative rural areas of Germany. The Reichswehr leadership considered them not only physically superior to young men from the cities but also as able to stand up against the "temptations" of social democracy.

In 1926 Reichstag President Paul Löbe

Paul Gustav Emil Löbe (14 December 1875 – 3 August 1967) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), a member and president of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic, and member of the Bundestag of West Germany. He ...

proposed to make recruitment dependent on physical fitness only in order to make the composition of the Reichswehr reflect more closely that of society as a whole. The proposal led to fierce opposition from the Reichswehr and conservative circles, both of which believed that opening the Reichswehr to all social groups would lower its effectiveness. Löbe’s proposal did not pass.

The Reichswehr saw itself as a ‘ cadre army’ or ‘Leader army’ (‘’), which meant that every soldier was trained in the skills needed to gain higher levels of responsibility. This was to become a basic prerequisite for the rapid growth of the army after the proclamation of military sovereignty by the Nazi regime in 1935.

Officers in the Reichswehr

Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty, the Reichswehr was allowed 4,000 officers, while the could have 1,500 officers and deck officers. The actual Reichswehr officer corps numbered 3,718, down from 227,081 in 1918, of whom 38,118 were career officers. The officers transferred to the Reichswehr were almost all general staff officers. Of the approximately 15,000 men who had been promoted to officers during the war, the Reichswehr took on only a few, as these front-line officers were seen as alien to officer life in the mess hall, barracks and society. Democratically-minded officers were not accepted into the force. Radical nationalist officers were with few exceptions removed, especially after the Kapp Putsch. The political attitude of the officer corps was monarchist, although outwardly they posed as loyal to the Republic. Even though the German nobility, which was officially abolished in August 1919, had accounted for only 0.14% of the pre-war German population, an average of 23.8% of the officers in the Reichswehr were from noble backgrounds. The proportion of former noble officers in the individual branches of the armed forces varied greatly. In 1920 they made up 50% of the officers in the cavalry but only 5% in the infantry and 4% in the sappers. Of the approximately 1,000 non-commissioned officers promoted to officers in 1919, by 1928 only 117 remained, or 3.5% of the total officers in the Reichswehr. Since the Reich government did not bring the officer candidate recruitment process under state control, regimental commanders in the Reichswehr continued to be responsible for selecting officer candidates, as they had in the old Imperial Army. Those admitted came almost exclusively from circles traditionally close to the military. In 1926, 96% of the officer candidates came from the upper social classes and nearly 50% from officer families. The homogeneity of the Reichswehr officer corps was in fact greater than it had been during the Empire. In 1912/13 only 24% of officers had come from families of active or former officers.The Reichswehr in the Weimar Republic

By assuring Reich Chancellor Ebert of its loyalty in the November 1918 Ebert-Groener Pact, the military had ensured the survival of the new government. In the crisis-ridden early 1920s, the Republic used the Reichswehr primarily to fight insurgent left-wing forces, such as during theSpartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolutio ...

in Berlin in 1919.

Cooperation with the Freikorps

Wherever the Treaty of Versailles tied the Reichswehr’s hands or its own manpower was insufficient, it left ‘national defense’ – e.g. border skirmishes against Polish and Lithuanian irregulars, or deployment against theRuhr Red Army

The Ruhr Red Army (13 March – 12 April 1920) was an army of between 50,000 and 80,000 left-wing workers who conducted what was known as the Ruhr Uprising (''Ruhraufstand''), in the Weimar Republic. It was the largest armed workers' uprising in ...

in the demilitarized Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

– to the Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, regar ...

, which although officially disbanded in 1920 continued to operate. The Reichswehr cooperated with nationalist Freikorps units when it took action against leftist governments in Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

and Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

in October and November 1923 during the so-called ‘ Reich executions’ – interventions against an individual state led by the central government to enforce national law. The Reichswehr generals also maintained close contacts with politically right-wing, anti-republican military associations such as the Stahlhelm and Kyffhäuserbund

The Kyffhäuserbund ( en, link=yes, Kyffhäuser League) is an umbrella organization for war veterans' and reservists' associations in Germany based in Rüdesheim am Rhein. It owes its name to the Kyffhäuser Monument (german: Kyffhäuserdenkmal ...

, although the Reichswehr officially described itself as "apolitical".

Passivity during the Kapp Putsch

In March 1920 Germany’s political leadership did not use the Reichswehr against the

In March 1920 Germany’s political leadership did not use the Reichswehr against the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

, a failed coup attempt against the Weimar Republic. It occurred after the government tried to demobilize two Freikorps brigades and one of them refused to disband. Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

, the chief of the ''Truppenamt

The ''Truppenamt'' or was the cover organisation for the German General Staff from 1919 through until 1935 when the General Staff of the German Army (''Heer'') was re-created. This subterfuge was deemed necessary in order for Germany to be seen ...

'' – the disguised general staff of the Reichswehr – had previously spoken out against taking action, reportedly saying that “Reichswehr does not fire on Reichswehr”. Seeckt however had no command authority. The Chief of Army Command, and thus the highest military officer, Walther Reinhardt

Walther Gustav Reinhardt (; 24 March 1872 in Stuttgart – 8 August 1930 in Berlin) was a German officer who served as the last Prussian Minister of War and the first head of the army command (''Chef der Heeresleitung'') within the newly create ...

, was in favor of using loyal Reichswehr units to suppress the putsch, but neither Reichswehr Minister Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske (9 July 1868 – 30 November 1946) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (''Reichswehrminister'') of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske has been a cont ...

nor the Reich government gave the order to deploy. (By contrast, the left-wing Ruhr Uprising, which began during the Kapp Putsch in the Ruhr and Saxony, was ruthlessly put down with the active involvement of the Reichswehr.) As a result of the Kapp putsch, the Reich Minister of Defense, Gustav Noske of the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

(SPD), was replaced by Otto Geßler

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a Classical liberalism, liberal German politician during the Weimar Republic. From 1910 until 1914, he was mayor of Regensburg and from 1913 to 1919 mayor of Nuremberg. He ...

of the German Democratic Party

The German Democratic Party (, or DDP) was a center-left liberal party in the Weimar Republic. Along with the German People's Party (, or DVP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It was formed in 1918 from the ...

(DDP).

Circumvention of the Treaty of Versailles

Reichswehr leadership began early on to circumvent the arms restrictions in the Versailles Treaty through a series of secret and illegal measures. They included the clandestine establishment of theBlack Reichswehr

Black Reichswehr (german: Schwarze Reichswehr) was the name for the extra-legal paramilitary formations promoted by the German Reichswehr army during the time of the Weimar Republic; it was raised despite restrictions imposed by the Versailles Tre ...

, unauthorized weapons testing in the Soviet Union, the establishment of a Leaders’ Assistant Training School which was intended to compensate for the forbidden General Staff training, and the maintenance of the General Staff in the newly created . Under the code name ‘Statistical Society’, plans for an armaments industry were worked out with the Reich Federation of German Industry. With the help of retired officers, sports schools for training infantrymen were founded, most of them near former military training areas, where exercise instructors for military sports were trained. This took place, especially in northern Germany, with the support of the Stahlhelm, a veterans’ organization that was part of the Black Reichswehr. Other aids in military training included the use of dummy tanks for exercise purposes.

Secret cooperation with the Soviet Union

In February 1923 the new Chief of the , Major General Otto Hasse, traveled to Moscow for secret negotiations. Germany was to support the development of Soviet industry andRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

commanders were to receive general staff training in Germany. In return, the Reichswehr was able to expand secretly in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles. It was given the opportunity to obtain artillery from the Soviet Union, to train aviation and tank specialists on Soviet soil, and to have chemical warfare agents manufactured and tested. A secret Reichswehr aviation school and testing facility was established at Lipetsk

Lipetsk ( rus, links=no, Липецк, p=ˈlʲipʲɪtsk), also romanized as Lipeck, is a city and the administrative center of Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the banks of the Voronezh River in the Don basin, southeast of Moscow. Populat ...

, where some 120 military pilots, 100 aerial observers, and numerous ground personnel were trained as the core of a future German air force. At Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering a ...

, tank specialists were trained, but not until 1930 and to a number of only about thirty. At the Tomka gas test site

Tomka gas test site (german: Gas-Testgelände Tomka) was a secret chemical weapons testing facility near a place codenamed Volsk-18 (Wolsk, in German literature), 20 km off Volsk, now Shikhany, Saratov Oblast, Russia created within the frame ...

near Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901,36 ...

, chemical warfare agents were jointly tested and developed.

In December 1926 the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann

Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann (26 July 1865 – 29 November 1939) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In the first quarter of the 20th century he played a leading role in both his party and in the young Weimar ...

disclosed the collaboration with the Soviet Union to the Reichstag, toppling the government under Wilhelm Marx

Wilhelm Marx (15 January 1863 – 5 August 1946) was a German lawyer, Catholic politician and a member of the Centre Party. He was the chancellor of Germany twice, from 1923 to 1925 and again from 1926 to 1928, and he also served briefly as the ...

. In 1931 Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (; 3 October 1889 – 4 May 1938) was a German journalist and pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German re-armament.

As editor-in-chief of the magazine ''Die ...

and Walter Kreiser were convicted of espionage in the ''Weltbühne'' Trial for a 1929 report in the weekly '' Weltbühne'' on the collaboration, which was by then already known.

The crisis in Bavaria and the Beer Hall Putsch

In response to unrest in Bavaria, Reich PresidentFriedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

transferred executive power to Reichswehr Minister Geßler in November 1923. True power thus rested with Hans von Seeckt, the head of the army command, who prevented a ‘Reich execution’ (see also Cooperation with the Freikorps, above) against the Bavarian government under Gustav Ritter von Kahr

Gustav Ritter von Kahr (; born Gustav Kahr; 29 November 1862 – 30 June 1934) was a German right-wing politician, active in the state of Bavaria. He helped turn post–World War I Bavaria into Germany's center of radical-nationalism but was the ...

. Kahr had been named State Commissioner when the Bavarian Minister President declared martial law. Kahr had designs to overthrow the Weimar Republic and was at first co-operating with Adolf Hitler but then broke with him before Hitler began the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

on 8 November. The Reichswehr’s Bavarian military district commander, Otto von Lossow

Otto Hermann von Lossow (15 January 1868 – 25 November 1938) was a Bavarian Army and then German Army officer who played a prominent role in the events surrounding the attempted Beer Hall Putsch by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in November 19 ...

, supported Kahr and refused to carry out orders from Geßler to suppress the unrest. Ebert and Seeckt then relieved him of his command, although Seeckt sympathized with the government in Munich. In February 1924 Seeckt relinquished the executive powers he had received through Ebert.

Seeckt and the events of 1924–1932

The 1925Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, during 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central an ...

ruled out any forcible change in Germany’s western borders, and in 1926 Germany joined the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. While war continued to be seen in the Reichswehr as a means to achieve political goals, government policy under the Locarno Treaties and the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

, which resolved the issue of German reparations payments to the victorious powers, was oriented more toward maintaining peace and international understanding. Seeckt and his officers were opposed to joining the League of Nations and saw their existence threatened by the pacifism of Germany’s left.

After the election of Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

as Reich President in 1925, his status as victor in the 1914 Battle of Tannenberg

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between Russia and Germany between 26 and 30 August 1914, the first month of World War I. The battle resulted in the almost complete destruction of the Russ ...

made him a figure with whom Reichswehr soldiers identified. Seeckt was forced to resign on 9 October 1926 because he had invited the son of the former emperor Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

to attend army maneuvers in the uniform of the old imperial First Foot Guards without first seeking government approval. It created a storm when the republican press publicized the transgression. Reichswehr Minister Otto Geßler

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a Classical liberalism, liberal German politician during the Weimar Republic. From 1910 until 1914, he was mayor of Regensburg and from 1913 to 1919 mayor of Nuremberg. He ...

told President von Hindenburg that Seeckt had to resign or he would himself resign. He was supported by the cabinet, so Hindenburg asked for and received Seeckt's resignation.

Seeckt was succeeded by

Seeckt was succeeded by Wilhelm Heye

August Wilhelm Heye (31 January 1869, Fulda – 11 March 1947, Braunlage) was a German officer who rose to the rank of Generaloberst and became head of the Army Command within the Ministry of the Reichswehr in the Weimar Republic. One of his ...

, although it was primarily Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last chancellor of Germany (before Adolf Hitler) during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by ...

who gained additional power. Under his leadership, the Reichswehr intervened in politics more often in order to achieve its goals, with the result that the Republic and the Reichswehr moved closer together.

In February 1927 the Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control

The term Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control was used in a series of peace treaties concluded after the First World War (1914–1918) between different countries. Each of these treaties was concluded between the Principal Allied and A ...

, which until then had supervised disarmament, withdrew from Germany.

The 1928 decision to build the pocket battleship ''Deutschland

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

'', which was in compliance with the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles and was a matter of prestige, caused problems for the Social Democrat Reich Chancellor Hermann Müller because his party had campaigned against the ship, but his cabinet members voted for it in order to save the coalition government. For the Reichswehr leadership, the vote was a landmark political decision. The 1929 budget included the first installment for the ''Deutschland’s'' sister ship, the '' Admiral Scheer''.

The rapprochement between the Republic and the Reichswehr brought the greatest gains to the Reichswehr. It achieved an increase in the defense budget, and criticism of the increase was seen as an attack on the Reichswehr and thus on the state.

The end of the Weimar Republic

Because of Reich President Hindenburg’s support for the Reichswehr, the presidential cabinets from 1930 onward increased its power. ChancellorHeinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

was embraced as a former soldier by the Reichswehr, and he spared it from his unpopular austerity measures. Franz von Papen and General Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last chancellor of Germany (before Adolf Hitler) during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by ...

, the two Reich chancellors who followed Brüning, considered using the Reichswehr to abolish democracy. In addition, one of the presidential cabinets’ main objectives was a revision of the Treaty of Versailles in the interest of the Reichswehr.

In 1931 and 1932, a series of actions by the Reichswehr and its leadership showed its increasing power and drift towards the Nazis:

* When the Harzburg Front, an anti-democratic alliance that included the Nazi Party, was formed in 1931, high-ranking members of the Reichswehr were present.

* In 1932 Defense Minister Groener, under pressure from several German states, outlawed the Nazi

In 1931 and 1932, a series of actions by the Reichswehr and its leadership showed its increasing power and drift towards the Nazis:

* When the Harzburg Front, an anti-democratic alliance that included the Nazi Party, was formed in 1931, high-ranking members of the Reichswehr were present.

* In 1932 Defense Minister Groener, under pressure from several German states, outlawed the Nazi Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; literally "Storm Detachment") was the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its primary purposes were providing protection for Nazi ral ...

(SA) and Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe d ...

(SS). He did this in his capacity as acting Minister of the Interior, whereas his goal as Defense Minister was to integrate the SA into a non-partisan paramilitary force. Kurt von Schleicher, Groener’s subordinate at the Ministry of Defense, told him that by outlawing the SA he had lost the trust of the Reichswehr, and as a result he resigned as Defense Minister.

* On 13 September 1932, on the initiative of Generals Groener and von Schleicher, the Reich Board for Youth Training was founded for the military education of German youth. In July 1933, under Hitler’s chancellorship, it became part of the SA.

* In the so-called Prussian coup d'état of July 1932, violent unrest in Berlin, particularly a bloody clash between the SA and communists, led Chancellor Franz von Papen to use an emergency decree issued by President von Hindenburg under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution to temporarily transfer executive power in Berlin and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

to the Reichswehr.

According to historian Klaus-Jürgen Müller, the German military strove for Germany to obtain a "position of world power". He identified two tendencies that were united in this long-term goal but that advocated different methods. One "adventurous" direction, represented by Hans von Seeckt, espoused a German-Soviet war of revenge against Poland and France. The other, more "modern" direction, represented by Kurt von Schleicher, which prevailed at the end of the 1920s, relied on a combination of political, military and economic factors. Firstly, Germany's economic position was to be strengthened and France relegated to the role of a junior partner. The supremacy thus gained in Europe was to form the basis for a position of world power. Müller sees in this one of the "lines of continuity" of German development from the Empire to National Socialism and the cause of an "entente" between groups of the traditional military elites and the Hitler movement in 1933. Hitler was dependent on their support in seizing power, while the latter in turn needed Hitler's supporters as a "mass base".

State within the state

In spite of Wilhelm Groener’s 1918 assurance in the Ebert-Groener Pact of the military’s loyalty to the government, most military leaders refused to accept the democratic Weimar Republic as legitimate. The Reichswehr under the leadership of Hans von Seeckt operated largely outside of the control of the politicians. Members of the Reichswehr did not have the right to vote, were subject to internal Reichswehr jurisdiction, and were thus detached from the social and political world. Because of the Ebert-Groener Pact and the Reichswehr's direct subordination to the Reich President, it was able to ensure itself of extensive internal autonomy. It used this to refuse to obey the Reich government, as it did for example during the Kapp Putsch. The autonomy, which included the selection of personnel as well as its code of values and belief that it served the state rather than the form of government, combined with its own jurisdiction under the Reich President to make the Reichswehr a ‘state within a state’ that was difficult to control. In 1928 the Reichswehr created the , or Office of Ministerial Affairs, under Kurt von Schleicher, to lobby politicians. The German historian Eberhard Kolb wrote that “from the mid-1920s onwards the Army leaders had developed and propagated new social conceptions of a militarist kind, tending towards a fusion of the military and civilian sectors and ultimately a totalitarian military state.”The Reichswehr under Hitler

After becoming chancellor at the end of January 1933, Adolf Hitler presented his government program to the generals on 3 February. Among other things, he promised them that the Reichswehr would remain Germany's sole armed force and announced the reintroduction of conscription. The Reichswehr hoped for increased efforts to revise the Treaty of Versailles and the building of a strong military and firm state leadership. But it also feared that the Reichswehr would be supplanted by the 3 million member SA. SA leader Ernst Röhm and his colleagues thought of their force as the future army of Germany, replacing the smaller Reichswehr and its professional officers. The Reichswehr supported Hitler in taking power away from the SA in the summer of 1934. Röhm wanted to become Minister of Defense, and in February 1934 demanded that the much smaller Reichswehr be merged into the SA to form a true people's army. This alarmed both political and military leaders, and to forestall the possibility of a coup Hitler sided with conservative leaders and the military. In theNight of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

(30 June–2 July 1934) Röhm and the leadership of the SA were murdered along with many other political adversaries of the Nazis, including Reichswehr generals Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last chancellor of Germany (before Adolf Hitler) during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by ...

and Ferdinand von Bredow

Ferdinand von Bredow (16 May 1884 – 30 June 1934) was a German '' Generalmajor'' and head of the '' Abwehr'' (the military intelligence service) in the Reich Defence Ministry and deputy defence minister in Kurt von Schleicher's short-lived ca ...

. The Reichswehr officer corps acknowledged the murders without objection.

During 1933 and 1934 the Reichswehr began a secret program of expansion. In December 1933 the army staff decided to increase the active strength to 300,000 men in 21 divisions. On 1 April 1934, between 50,000 and 60,000 new recruits entered the force and were assigned to special training battalions. The original seven infantry divisions of the Reichswehr were expanded to 21, with military district headquarters increased to the size of a corps headquarters on 1 October 1934. These divisions used cover names to hide their divisional size, but during October 1935 they were dropped. Also during October 1934, the officers who had been forced to retire in 1919 were recalled. Those who were no longer fit for combat were assigned to administrative positions, thus releasing fit officers for front-line duties.

On 2 August 1934, the day Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died, Reichswehr Minister

During 1933 and 1934 the Reichswehr began a secret program of expansion. In December 1933 the army staff decided to increase the active strength to 300,000 men in 21 divisions. On 1 April 1934, between 50,000 and 60,000 new recruits entered the force and were assigned to special training battalions. The original seven infantry divisions of the Reichswehr were expanded to 21, with military district headquarters increased to the size of a corps headquarters on 1 October 1934. These divisions used cover names to hide their divisional size, but during October 1935 they were dropped. Also during October 1934, the officers who had been forced to retire in 1919 were recalled. Those who were no longer fit for combat were assigned to administrative positions, thus releasing fit officers for front-line duties.

On 2 August 1934, the day Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died, Reichswehr Minister Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German General Staff officer and the first Minister of War in Adolf Hitler's government. After serving on the Western Front in World War I, Blomberg was appointed chi ...

, who was originally to have helped ‘tame’ the Nazis, had the Reichswehr swear its oath personally to Hitler. Under the Weimar Republic the oath had been to the constitution.

On 1 March 1935, the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

was established and on 16 March universal conscription reintroduced, both of which violated the Treaty of Versailles. In the same act the Reichswehr was renamed the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

''. On 1 June 1935 the (the army contingent of the Reichswehr) was renamed ‘’ (‘army’) and the Reichsmarine became the ‘''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

''’ (‘war navy’).

See also

* *Ministry of the Reichswehr

The Ministry of the Reichswehr or Reich Ministry of Defence (german: Reichswehrministerium) was the defence ministry of the Weimar Republic and the early Third Reich. The 1919 Weimar Constitution provided for a unified, national ministry of defen ...

* Weimar paramilitary groups

Paramilitary groups were formed throughout the Weimar Republic in the wake of Imperial Germany's defeat in World War I and the ensuing German Revolution. Some were created by political parties to help in recruiting, discipline and in preparation ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Axis History Factbook — Reichswehr

Feldgrau's overview of the Reichswehr

The Archives of technical Manuals 1900–1945 (includes the Reichswehr-regulations)

{{Authority control Military of the Weimar Republic Military history of Germany