Reformation In The Kingdom Of Hungary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The Royal Council was the composite kingdom's most important decision-making body. It was dominated by the realm's high officers and the Roman Catholic bishops. They also controlled the Diets, or legislative assemblies. The peculiar administrative system of Transylvania had its origin in the co-existence of three privileged groups, known as "nations". The noblemen, known as the Hungarian nation, dominated the counties in central and western Transylvania. The Hungarian-speaking

The Royal Council was the composite kingdom's most important decision-making body. It was dominated by the realm's high officers and the Roman Catholic bishops. They also controlled the Diets, or legislative assemblies. The peculiar administrative system of Transylvania had its origin in the co-existence of three privileged groups, known as "nations". The noblemen, known as the Hungarian nation, dominated the counties in central and western Transylvania. The Hungarian-speaking  As the Ottomans could never conquer the entire kingdom, its territory was divided into three parts. The Habsburgs' realm, or

As the Ottomans could never conquer the entire kingdom, its territory was divided into three parts. The Habsburgs' realm, or

News of Luther's activity reached Hungary shortly after he published his ''Ninety-five Theses''. Merchants from Hermannstadt likely learnt of Luther's ideas at the

News of Luther's activity reached Hungary shortly after he published his ''Ninety-five Theses''. Merchants from Hermannstadt likely learnt of Luther's ideas at the  Laymen played a preeminent role in the dissemination and reception of reformist ideas. Both Luther's denial of priestly privileges and Zwingli's picture of the reform movement as a force transforming church and society alike endorsed lay participation. The first Protestant evangelists were "lay people of both sexes" who preached outside church buildings—in private homes or in public places. Most leaders of the towns with significant German population were receptive to anti-Catholic preaching. Pemfflinger expelled the Catholic parish priest and the Dominican friars from Hermannstadt around 1530. The wealthy mining town, Neusohl (

Laymen played a preeminent role in the dissemination and reception of reformist ideas. Both Luther's denial of priestly privileges and Zwingli's picture of the reform movement as a force transforming church and society alike endorsed lay participation. The first Protestant evangelists were "lay people of both sexes" who preached outside church buildings—in private homes or in public places. Most leaders of the towns with significant German population were receptive to anti-Catholic preaching. Pemfflinger expelled the Catholic parish priest and the Dominican friars from Hermannstadt around 1530. The wealthy mining town, Neusohl (

The Catholic

The Catholic

An experienced debater,

An experienced debater,  Religious discussions continued. In June 1557, the two Transylvanian church districts' joint synod completed a common confessional document, the Kolozsvár Consensus. It mirrored Luther's views on Eucharist, but in September the Protestant pastors of Partium adopted a Calvinist formula. The Saxon priests sent a copy of the Kolozsvár Consensus for a review to Melanchthon. The next Diet incorporated Melanchthon's assessment in a decree and outlawed Sacramentarians, but the ban could not stop the development of Reformed theology. Szegedi's student,

Religious discussions continued. In June 1557, the two Transylvanian church districts' joint synod completed a common confessional document, the Kolozsvár Consensus. It mirrored Luther's views on Eucharist, but in September the Protestant pastors of Partium adopted a Calvinist formula. The Saxon priests sent a copy of the Kolozsvár Consensus for a review to Melanchthon. The next Diet incorporated Melanchthon's assessment in a decree and outlawed Sacramentarians, but the ban could not stop the development of Reformed theology. Szegedi's student,

Religious innovations continued in eastern Hungary and the most radical preachers started to openly reject the dogma of Trinity early in the 1560s. One of them, Tamás Arany was banned from Debrecen by Péter Melius. Giorgio Biandrata stated that all discussions about Christ's nature are unbiblical because God did not want to reveal all theological secrets to humankind. He recognized that the Reformed congregations' autonomy facilitated the spread of radical views and convinced Ferenc Dávid to abandon trinitarian theology. Dávid endorsed a radical theology, but he did not embrace most radical reformers' political activism. In his publication of texts from Servetus's works, Dávid emphasized Christ's poverty, but also stated that Christ's example should be followed "to the extent that it was possible to do so". The Kolozsvár magistrates appreciated Dávid's social conservativism and ordered the local pastors to comply with Dávid's teaching. Between 1566 and 1570, Kolozsvár became predominantly antitrinitarian, with repressed Reformed and Catholic minority communities.

For Melius harshly criticized Dávid, King John Sigismund ordered them to discuss their views in public at Gyulafehérvár in April 1566. After the debate, John Sigismund praised Melius, and the Transylvanian clergy reassured their adherence to the dogma of Trinity. Dávid ignored their decision and refused to abandon antitrinitarianism. In February 1567, Melius held a synod in Debrecen, condemning Dávid and Dávid's followers for heresy. The synod adopted a strictly Reformed confession of faith, known as Debrecen Confession, and ordered the removal of altars,

Religious innovations continued in eastern Hungary and the most radical preachers started to openly reject the dogma of Trinity early in the 1560s. One of them, Tamás Arany was banned from Debrecen by Péter Melius. Giorgio Biandrata stated that all discussions about Christ's nature are unbiblical because God did not want to reveal all theological secrets to humankind. He recognized that the Reformed congregations' autonomy facilitated the spread of radical views and convinced Ferenc Dávid to abandon trinitarian theology. Dávid endorsed a radical theology, but he did not embrace most radical reformers' political activism. In his publication of texts from Servetus's works, Dávid emphasized Christ's poverty, but also stated that Christ's example should be followed "to the extent that it was possible to do so". The Kolozsvár magistrates appreciated Dávid's social conservativism and ordered the local pastors to comply with Dávid's teaching. Between 1566 and 1570, Kolozsvár became predominantly antitrinitarian, with repressed Reformed and Catholic minority communities.

For Melius harshly criticized Dávid, King John Sigismund ordered them to discuss their views in public at Gyulafehérvár in April 1566. After the debate, John Sigismund praised Melius, and the Transylvanian clergy reassured their adherence to the dogma of Trinity. Dávid ignored their decision and refused to abandon antitrinitarianism. In February 1567, Melius held a synod in Debrecen, condemning Dávid and Dávid's followers for heresy. The synod adopted a strictly Reformed confession of faith, known as Debrecen Confession, and ordered the removal of altars,

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in the Kingdom of Hungary started around 1520 and resulted in the conversion of most Hungarians from Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

to a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

denomination by the end of the 16th century. Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

was a Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

an regional power in the late 15th century. It was a multhiethnic composite monarchy with a significant non-Catholic, predominantly Greek Orthodox, population.

Background

Reformation in Europe

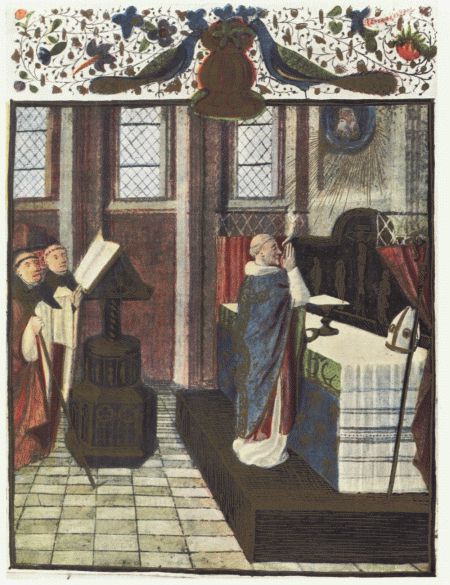

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

was the central element of devotional life in Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic ...

in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

. During the ceremony, bread and wine were served to commemorate Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

's Last Supper before his crucifixion. The 13th-century scholastic theologian, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, developed the idea of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of th ...

, stating that the substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis ...

of the bread and wine turned into the substance of the Body

Body may refer to:

In science

* Physical body, an object in physics that represents a large amount, has mass or takes up space

* Body (biology), the physical material of an organism

* Body plan, the physical features shared by a group of anima ...

and Blood of Christ during the liturgy of Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. Most faithful believed that prayers for the dead, indulgence grants from church authorities and works of mercy could shorten the afterlife sufferings of sinful people's souls. Laymen's desire to a godly way of life developed a contemplative method of piety around 1400. This '' Devotio Moderna'' enabled ordinary people to embrace the clerics' high standards without taking the holy orders. Those who challenged traditional doctrines had to face persecution by church authorities. People were also persecuted for witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

especially after late scholastic theologians developed the theoretical basis of the magicians' accusation not only of maleficium

Maleficium may refer to:

* ''Maleficium'' (sorcery), a Latin term meaning "evildoing", "wrongdoing", or "mischief", and describing malevolent, dangerous, or harmful magic

* ''Maleficium'' (album), a 1996 album by Morgana Lefay

* ''Maleficium'', ...

but also of idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of a cult image or "idol" as though it were God. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, the Baháʼí Faith, and Islam) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the A ...

. Witch-hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The Witch trials in the early modern period, classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and European Colon ...

and the hunt for " heretics" could go hand in hand, like in the western Alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

regions where Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

were brought to court for witchcraft.

An elaborate church organization secured the unity of Western Christianity. Clergymen— secular clerics and monks

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedicat ...

—were expected to remain celibate

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, th ...

(unmarried and chaste). Secular clerics were organized into diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, pro ...

s, each under a bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

's authority. A diocese included smaller territorial units, known as parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

. The monks lived a regulated life within religious communities, many of which formed international organizations. The pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

stood at the head of the church organization, but the co-existence of two, later three, rival lines of popes subverted the traditional order during the Western Schism (from 1378 to 1417). An Oxford theologian, John Wyclif

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of O ...

, challenged the traditional ecclesiastic system in the 1370s. He rejected the clergymen's privileges, teaching that all faithful chosen by God had a direct access to an eternal invisible Church. His followers, the Lollards, were outlawed, but a royal marriage between England and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

facilitated the spread of his teachings in Central Europe. A professor at the Prague University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, underg ...

, Jan Hus, accepted some of Wyclif's views and his sermons demanding a Church reform won popularity among the Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

. Hus was burned at the stake for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

in 1415. Soon a civil war, colored with ethnic tensions between Czechs and Germans, broke out in Bohemia. It was closed by the Peace of Kutná Hora that legalized moderate Hussitism, or Utraquism, in Bohemia in 1485.

From the early 15th century, manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

s containing Classical Greek philosophers' works were streaming to Catholic Europe from the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Humanist men of letters rediscovered Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Plato's believe in a reality beyond visible reality diverted them from the clear categories of scholastic theology. The study of Classical texts convinced them that some of the key documents of church history were forgeries or unworthy collections of poor texts. The spread of paper manufacturing and the introduction of printing machines with movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuatio ...

had a lasting impact on religious life. Bibles translated from Latin to vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

s were among the first books printed in Germany, Italy, Spain and Bohemia in the 1460s and 1470s. The Dutch humanist Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

completed a critical edition of the Latin translation of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

between 1516 and 1519. His translation challenged the textual basis of some Catholic doctrines, including the sacrament of penance and the intercession of saints

Intercession of the Saints is a Christian doctrine held by the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. The practice of praying through saints can be found in Christian writings from the 3rd century onward.

The 4th-century Apo ...

.

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

decided to complete the building of the St. Peter's Basilica and issued indulgence grants to finance the project in 1515. Around the same time, the German theologian Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

was delivering lectures on salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

at the Wittenberg University

Wittenberg University is a private liberal arts college in Springfield, Ohio. It has 1,326 full-time students representing 33 states and 9 foreign countries. Wittenberg University is associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

...

. His studies convinced him that indulgence grants were useless and summarized his views in his ''Ninety-five Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

'' on 31 October 1517. The Pope excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

him for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, but Luther publicly burned the papal bull in December 1520. Luther rejected the clerics' privileged status and denied that works of merit could influence salvation. Instead, he embraced the idea of , or justification by faith alone. Luther's co-worker, Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, summarized the principal theses of Evangelical theology in the Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, ''Confessio Augustana'', is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Re ...

in 1530. As the new theology gain popularity among the German princes, the principle ("whose realm, his religion") emerged, emphasizing the princes' right to regulate their subjects' spiritual life. Its application transformed Germany into a mozaic of predominantly Evangelical or Catholic principalities. The principle also established the secular rulers' claim to take responsibility for church administration and to seize church property. In 1529, the princes and free cities sympathizing with Luther's theology staged a protest against the anti-Lutheran decisions adopted at Imperial Diet of Speyer, hence the name "Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

" for 16th-century religious reformers and their followers.

Luther's theology did not satisfy all reformers' expectations. He never abandoned his devotion to the Eucharist and insisted on the baptism of children. Under the influence of the parish priest, Huldrych Zwingli, who did not regard the Eucharist more than a symbolic act, the city council of Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

outlawed the Mass in 1525. A Catholic priest's illegitimate son, Heinrich Bullinger, developed an interim formula to conciliate Luther's and Zwingli's views on Eucharist, describing it as a mark of the covenant between God and humankind. The most radical reformers

The Radical Reformation represented a response to corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Ra ...

rejected the doctrine of Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

(the believe in one God consisting of three persons, Father, Son

A son is a male offspring; a boy or a man in relation to his parents. The female counterpart is a daughter. From a biological perspective, a son constitutes a first degree relative.

Social issues

In pre-industrial societies and some current c ...

and Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

). A Navarrese

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

scholar, Michael Servetus, adopted this antitrinitarian theology in the hope of facilitating the union of Christianity, Islam and Judaism. In 1534 Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

radicals seized Münster, legalized polygyny

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any o ...

and ordered the redistribution of property, but the local bishop crushed the revolt in a year.

A French Protestant refugee who settled in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

regarded the Anabaptists as fanatics. To explain theological diversity, Calvin developed the idea of double predestination, stating that God had chosen some people for salvation, others for damnation. He rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation and regarded the sacramental bread as a symbol of Christ's heavenly body. Calvin's theology gave rise to the development of a new Protestant denomination, known as Reformed Christianity or Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

. Most German states and Scandinavia remained loyal to Luther's teachings, but English, French and Dutch translations of Calvin's works spread his ideas in Scotland, France and the Netherlands. Theological debates brought about the " Era of Confessionalization": the Calvinists summarized their theologies in confessional documents, including the 1563 Heidelberg Catechism

The Heidelberg Catechism (1563), one of the Three Forms of Unity, is a Protestant confessional document taking the form of a series of questions and answers, for use in teaching Calvinist Christian doctrine. It was published in 1563 in Heidelberg, ...

. Although Luther and Calvin rejected significant Catholic doctrines, they embraced Catholic demonology and never denied the Devil's authority. As even the most religious individuals were unable to continuously adhere to Christian moral standards, scapegoating was not alien to them. When feeling compunction about their immoral acts or thoughts, pious Christians tended to attribute them to the influence of others, accusing them of witchcraft. The new emphasis on a pure Christianity gave rise to the persecution of elements of popular religion, including amulets or traditional healing practices.

The Reformation movement exerted influence on religious life and theology throughout Europe, but it thrived particularly in regions under a weak central authority. Radical reformers' acts alarmed many people and the newly raised nostalgia for traditional church values gave an impetus to Catholic renewal, culminating in the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

. A courtier turned friar, Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola, Society of Jesus, S.J. (born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; eu, Ignazio Loiolakoa; es, Ignacio de Loyola; la, Ignatius de Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Spain, Spanish Catholic ...

, established a highly centralized religious order, the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

. Popularly known as Jesuits, the Society's members were rather missionaries or teachers than ordinary priests from the 1550s. The Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

(1545–1563) passed decrees to renew and reinforce Catholic theology and church life. In response to Luther's concept about a sinful humanity unable to fulfil divine law, the Council emphasized that humankind retained free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

after the Fall. The council's last session ordered the foundation of seminaries to secure the training of parish priests.

Early Modern Hungary

TheKingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

was a Central European regional power, encompassing about of land in the 15th century. It was a composite monarchy: the Hungarian kings

This is a list of Hungarian monarchs, that includes the grand princes (895–1000) and the kings and ruling queens of Hungary (1000–1918).

The Principality of Hungary established 895 or 896, following the 9th-century Hungarian conquest of the ...

also ruled Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, and two provinces, Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

(in the east) and Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja ...

(in the southwest), had their own peculiar administrative systems. Hungary was a multi-ethnic realm, with most Hungarian-speakers living in the central regions and ethnic minorities—among them Slovaks, Romanians and Serbs—inhabiting the periphery. Germans made up the majority of the townspeople. They had regular commercial contacts with the merchants of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

and many of them had family links with southern German and Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

n burghers. Although predominantly Catholic, Hungary was a multi-confessional country, with a significant Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

population. The Orthodox had their own churches and practiced their religion without major restrictions.

According to modern historians' estimations, the kingdom was home to 3–4 million people in the late 1490s. About 3,2–4,2% of the population were nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

. About 90,000 burghers lived in the royal free boroughs; these were fortified towns and cities with extensive autonomy. Conservative jurists argued that everybody else (those who were neither nobles nor burghers) were to be regarded serfs, but their approach ignored reality. Townspeople in the market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

s—unfortified settlements with the right to hold weekly markets—had a higher level of personal freedom than villagers. Rural communities were also divided. Artisans were rewarded with tax-exemption, but most peasants paid seignorial taxes to their lords.

The Royal Council was the composite kingdom's most important decision-making body. It was dominated by the realm's high officers and the Roman Catholic bishops. They also controlled the Diets, or legislative assemblies. The peculiar administrative system of Transylvania had its origin in the co-existence of three privileged groups, known as "nations". The noblemen, known as the Hungarian nation, dominated the counties in central and western Transylvania. The Hungarian-speaking

The Royal Council was the composite kingdom's most important decision-making body. It was dominated by the realm's high officers and the Roman Catholic bishops. They also controlled the Diets, or legislative assemblies. The peculiar administrative system of Transylvania had its origin in the co-existence of three privileged groups, known as "nations". The noblemen, known as the Hungarian nation, dominated the counties in central and western Transylvania. The Hungarian-speaking Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

, who were responsible for the defence of eastern Transylvania, were organized into autonomous districts, or seats. The third nation, the German-speaking Transylvanian Saxons, inhabited parts of southern and northern Transylvania. They were also organized into seats and they elected their supreme leader, the , or royal judge. Some Saxon parishes were affiliated to the Bishopric of Transylvania, but the parishes in the church districts, or deaneries, of Hermannstadt and Kronstadt (now Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , german: link=no, Hermannstadt , la, Cibinium, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'', hu, Nagyszeben ) is a city in Romania, in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles the Ci ...

and Brașov in Romania) were subject to the Archbishops of Esztergom

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

. Bearing the title of primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

, the archbishops were the heads of the Hungarian Catholic Church.

The Hungarian kings had extensive authority over church affairs. Papal decrees did not come into force without their assent and they controlled appointments to episcopal see

An episcopal see is, in a practical use of the phrase, the area of a bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Phrases concerning actions occurring within or outside an episcopal see are indicative of the geographical significance of the term, mak ...

s. The Hungarian bishops' wealth was legendary, but they employed underpaid vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

s to perform their spiritual duties. The landowners held , or right of patronage, over the churches in their domains. The Diet also established their right to instal parish priests before their candidate was sanctioned by the bishop. On occasions, aristocrats consulted with the local communities before practicing their patronage right. The royal free boroughs and the wealthy Upper Hungarian mining towns could freely elect and dismiss their parish priests. They preferred ethnic German clergy, but the town councils often appointed a junior cleric to take care of the spiritual needs of the local Hungarian- or Slovakian-speaking community. Jan Hus's theology spread in the villages and market towns of Szerém County (now in Serbia) and Hussite preachers completed the Bible's first Hungarian translation. A papal inquisitor James of the Marches was appointed to purge the Hungarian Hussites in 1436.

King Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several mi ...

() made his court a center of Humanism. A member of the Florentine Platonic Academy

The Academy (Ancient Greek: Ἀκαδημία) was founded by Plato in c. 387 BC in Classical Athens, Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years (367–347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum. The Academy ...

, Francesco Bandini, was the King's close advisor and Bandini's friend, Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of ...

, dedicated his treatise on salvation to Corvinus. Humanistic ideas influenced a narrow circle of intellectuals. Most Hungarians preferred the traditional forms of spirituality and the personal piety of the was alien to them. Historian László Kontler describes the 16th century as "a particularly exciting period in the history of the Hungarian culture". An educated nun, Lea Ráskay

Lea Ráskay, O.P., (; early 16th century, sometimes also spelled ''Ráskai'') was a Hungarian nun and scholar of the 16th century.

Life

Ráskay was likely a descendant of that old Hungarian aristocratic family which would have gotten its name ...

, wrote a collection of the lives of saints for nunneries in the 1510s and 1520s. Wealthy individuals and guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s granted large sums to finance the erection of splendid triptych altarpieces in several churches.

After the expansion of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

reached Hungary's southern frontier in the late 1380s, Hungary resisted Ottoman attacks for more than a century. In 1513, Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

declared a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

against the Ottomans. About 40,000 Hungarian peasants took the cross, although the landowners tried to prevent their serfs from joining the campaign. Inflamed by radical Franciscan friars, the crusaders accused their lords of obstructing the holy war and rose up in an open rebellion under the command of György Dózsa

György Dózsa (or ''György Székely'',appears as "Georgius Zekel" in old texts ro, Gheorghe Doja; 1470 – 20 July 1514) was a Székely man-at-arms (and by some accounts, a nobleman) from Transylvania, Kingdom of Hungary who led a peasa ...

. Their demands included the unification of the Hungarian bishoprics into one diocese and the redistribution of church property. After the Transylvanian voivode, or royal governor, John Zápolya, inflicted a crushing defeat on Dózsa's army on 15 July 1514, the peasant revolt was crushed and the Diet limited the peasants' right to free movement. As the Hungarian kings could no more defend Croatia against Ottoman raids effectively, the Croatian aristocrats approached the neighboring Habsburg rulers for support.

The Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

Suleiman the Magnificent () nearly annihilated the Hungarian army in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

on 29 August 1526. The twenty-year-old King Louis II () drowned in a stream fleeing from the battlefield. John Zápolya and Louis's brother-in-law, Ferdinand of Habsburg, laid claim to the throne. For both claimants were elected kings at two separate Diets, Hungary was plunged into civil war. Regarding Hungary as a vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back to ...

, Suleiman acknowledged John as the lawful king, but neither claimants could take control of the whole country. The two kings agreed to divide the country in the 1538 Treaty of Várad (Oradea

Oradea (, , ; german: Großwardein ; hu, Nagyvárad ) is a city in Romania, located in Crișana, a sub-region of Transylvania. The county seat, seat of Bihor County, Oradea is one of the most important economic, social and cultural centers in the ...

, Romania), but the childless John acknowledged Ferdinand's right to reunite Hungary after his death. Days before John died in 1540, his wife, Isabella Jagiellon, gave birth to a son, John Sigismund. John's principal advisor, the Paulician

Paulicianism ( Classical Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, ; grc, Παυλικιανοί, "The followers of Paul"; Arab sources: ''Baylakānī'', ''al Bayāliqa'' )Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the ...

monk, George Martinuzzi, persuaded John's partisans to elect the infant boy king. Ferdinand's troops stormed into John Sigismund's eastern Hungarian kingdom

The Eastern Hungarian Kingdom ( hu, keleti Magyar Királyság) is a modern term coined by some historians to designate the realm of John Zápolya and his son John Sigismund Zápolya, who contested the claims of the House of Habsburg to rule the ...

, providing Suleiman with a pretext to intervene. The Ottoman army invaded Hungary and seized the kingdom's capital, Buda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

, without resistance on 29 August 1541. Suleiman confirmed John Sigismund's right to rule the land to the east of the river Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

and the Ottoman troops conquered the kingdom's central regions.

Royal Hungary

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

, included the western and northern regions; Martinuzzi assumed authority in the eastern Hungarian kingdom as regent for John Sigismund; and Ottoman Hungary became an integral part of the Ottoman Empire. Two separate Diets, both regarded as the Hungarian Diets' legal successors, developed in Royal Hungary and in eastern Hungary. The latter Diet emerged from the joint assemblies of the representatives of the Three Nations of Transylvania and of the delegates of the nobility of the Partium (the eastern Hungarian counties along Transylvania's borders). The eastern Hungarian Diet established each nation's right to regulate its own internal affairs. Ottoman Hungary was divided into , or provinces, each under the rule of a . Most nobles fled from the territory and settled in the unoccupied territory.

Martinuzzi enabled Ferdinand's mercenaries to take control of the eastern Hungarian kingdom in June 1551, forcing Queen Isabella and her son into exile. Martinuzzi was murdered by Ferdinand's henchmen, but the unpaid mercenaries could not prevent Ottoman attacks. In 1556, the Diet recalled John Sigismund and his mother from their exile. She ruled the country on her son's behalf until her death in 1559. John Sigismund was the Sultan's loyal vassal and participated in several Ottoman military campaigns against Royal Hungary. During his reign, most Székelys were deprived of important elements of Székely liberties (such as tax exemption) which caused discontent in Székely Land. Ferdinand's successor, Maximilian

Maximilian, Maximillian or Maximiliaan (Maximilien in French) is a male given name.

The name " Max" is considered a shortening of "Maximilian" as well as of several other names.

List of people

Monarchs

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459� ...

(), and Suleiman's son, Selim II

Selim II ( Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى ''Selīm-i sānī'', tr, II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond ( tr, Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunk ( tr, Sarhoş Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire ...

(), restored peace in the Treaty of Adrianople in 1568. John Sigismund abandoned the title of king in his treaty with Maximilian in 1570, but continued to rule his realm using the title of Prince of Transylvania. John Sigismund acknowledged the Habsburg kings' suzerainty and their right to reunite Transylvania with Royal Hungary after his childless death.

John Sigismund died in early 1571. The Three Nations' delegates ignored Maximilian's claim to Transylvania and elected a wealthy aristocrat Stephen Báthory () ruler. Báthory was the Ottomans' candidate, but he swore fealty to Maximilian in secret. Báthory was elected the ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

in 1575, but he maintained peace with the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. Maximilian was succeeded by his son, Rudolph (). After Báthory was succeeded by his underage nephew, Sigismund Báthory (), factionalism developed and faction leaders conducted vendettas against their opponents in the Transylvanian principality. Ottoman raids into Royal Hungary resumed and Sultan Murad III

Murad III ( ota, مراد ثالث, Murād-i sālis; tr, III. Murad; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Saf ...

() declared war against Rudolph in 1593. Unexpected Ottoman defeats during the first phase of the Long Turkish War strengthened anti-Ottoman sentiments and Sigismund Báthory concluded an alliance with Rudolph in 1595. The Ottomans quickly regained the initiative and Transylvania plunged into anarchy. In 1601, Rudolph's troops occupied the principality and his lieutenant, Giorgio Basta, introduced the rule of terror. The royal officials' arbitrary actions caused discontent in both Royal Hungary and Transylvania. Sigismund Báthory's maternal uncle, Stephen Bocskai, stirred up a revolt and occupied significant territory in Royal Hungary. The Treaty of Vienna restored peace and the Habsburgs acknowledged the re-establishment of the Transylvanian principality.

Beginnings

News of Luther's activity reached Hungary shortly after he published his ''Ninety-five Theses''. Merchants from Hermannstadt likely learnt of Luther's ideas at the

News of Luther's activity reached Hungary shortly after he published his ''Ninety-five Theses''. Merchants from Hermannstadt likely learnt of Luther's ideas at the Leipzig Trade Fair

The Leipzig Trade Fair (german: Leipziger Messe) is a major trade fair, which traces its roots back for nearly a millennium. After the Second World War, Leipzig fell within the territory of East Germany, whereupon the Leipzig Trade Fair became o ...

in 1519. One Thomas Preisner gave the first documented public reading of Luther's theses in Leibitz (Ľubica

Ľubica ( hu, Leibic, german: Leibitz, rue, Любіца) is a large village and municipality in Kežmarok District in the Prešov Region of north Slovakia. It is now a mostly housing development district with many panel block houses.

History

In ...

, Slovakia) in 1521. In a year, the German townspeople were enthusiastically discussing Luther's views in the Upper Hungarian mining towns. King Louis's guardian, George, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, entered into correspondence with Luther. Most German courtiers of Louis's wife, Mary of Habsburg

Mary of Austria (15 September 1505 – 18 October 1558), also known as Mary of Hungary, was queen of Hungary and Bohemia as the wife of King Louis II, and was later governor of the Habsburg Netherlands.

The daughter of Queen Joanna and ...

, symphathized with the reformist ideas, but she did not abandon her Catholic faith. Her chaplain, Konrad Cordatus, made no secret of his adherence to Lutheran theology and she dismissed him after the Pope excommunicated Luther. The ''Königsrichter'', Markus Pemfflinger, supported the spread of Lutheran ideas in Hermannstadt where songs mocking the " Papists", or Catholics, gained popularity.

The country's Hungarian- or Slavic-speaking population had no direct access to reformist literature for years. Most nobles were hostile towards Protestant ideas, because they were convinced Hungary could resist Ottoman invasions only with the Pope's support. István Werbőczy

István Werbőczy or Stephen Werbőcz (also spelled ''Verbőczy'' and Latinized to ''Verbeucius'' 1458? – 1541) was a Hungarian legal theorist and statesman, author of the Hungarian Customary Law, who first became known as a legal scholar ...

who represented Hungary at the Imperial Diet of Worms in 1521 entered into a public argument with Luther. Luther stated that the Hungarians should fight against their own sins rather than against the Ottomans whom he regarded as "God's scourge". The Hungarian noblemen took his words as an insult, denying their self-declared mission of serving at the bulwark of Christianity. The first anti-Lutheran edict was promulgated in Hungary on 24 April 1523; it ordered the persecution and execution of all Lutherans and the confiscation of their property. Ladislaus Szalkai Ladislaus or László Szalkai (1475-1526) was a Hungarian bishop, treasurer and chancellor.

Life

The son of a shoemaker from Mátészalka, he worked in the royal court from 1494, initially as a treasurer then as one of the royal secretaries. He was ...

, Archbishop of Esztergom, appointed commissioners to detect and destroy Evangelical literature, but the local magistrates obstructed them. In Sopron, a royal commission experienced that townspeople regularly gathered in taverns to discuss Luther's views and to criticize the Pope.

Anti-Lutheran legislation could not be enforced during the civil war that followed the Battle of Mohács. Six of the twelve Hungarian bishops perished at the battlefield. King Ferdinand appointed bishops to the vacant sees, but the Pope did not confirm them. Church property was unprotected; church buildings and monasteries were regularly sacked or expropriated. Neither king wanted to antagonize Protestant town leaders and aristocrats. Protestant itinerant preachers freely crossed the frontiers between Hungary and King Ferdinand's other realms. Some of them called themselves Neo-Utraquists to take advantage of the legal status of Utraquism in Bohemia. King John's most prominent supporters, mainly nationalist aristocrats, looked on Luther as a German innovator and remained unsympathetic towards him. John was a devout Catholic, but he was unwilling to persecute "heretics" after the Pope excommunicated him for his alliance with the Ottomans in 1529. Fear of social unrest hindered the spread of Protestant ideas, but no peasant movements followed the 1514 peasant war, because the serfs easily extracted exemptions from their lords in the wake of the Ottoman expansion.

Laymen played a preeminent role in the dissemination and reception of reformist ideas. Both Luther's denial of priestly privileges and Zwingli's picture of the reform movement as a force transforming church and society alike endorsed lay participation. The first Protestant evangelists were "lay people of both sexes" who preached outside church buildings—in private homes or in public places. Most leaders of the towns with significant German population were receptive to anti-Catholic preaching. Pemfflinger expelled the Catholic parish priest and the Dominican friars from Hermannstadt around 1530. The wealthy mining town, Neusohl (

Laymen played a preeminent role in the dissemination and reception of reformist ideas. Both Luther's denial of priestly privileges and Zwingli's picture of the reform movement as a force transforming church and society alike endorsed lay participation. The first Protestant evangelists were "lay people of both sexes" who preached outside church buildings—in private homes or in public places. Most leaders of the towns with significant German population were receptive to anti-Catholic preaching. Pemfflinger expelled the Catholic parish priest and the Dominican friars from Hermannstadt around 1530. The wealthy mining town, Neusohl (Banská Bystrica

Banská Bystrica (, also known by other alternative names) is a middle-sized town in central Slovakia, located on the Hron River in a long and wide valley encircled by the mountain chains of the Low Tatras, the Veľká Fatra, and the Kremnica Mo ...

, Slovakia), employed Evangelical town pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

s from 1530. Some senior magistrates tried to impede the Reformation, but they could rarely find Catholic priests to fill the vacant parishes. Town councils granted scholarships to young people for studies at Wittenberg and other academic centers of the Reformation, but professional Evangelical preachers were still rare. In the 1540s, a Croatian graduate from Wittenberg, Michael Radašin, was a most popular pastor in the mining towns. Some town councils were reluctant to pay a regular renumeration to the local clergy. The Neusohl town pastor, Martin Hanko, had to dedicate much time to the management of his pastorate's properties to support himself before the town agreed to exchange them for a fix salary. Some preachers' radicalism outraged the moderate townspeople. Wolfgang Schustel, had to leave Bartfeld ( Bardejov, Slovakia) for his strict views of public piety in 1531; his successor, Esaias Lang, was expelled for his Anabaptist sympathies. A moderate magistrate, Johannes Honter, prevented the town pastor from abolishing the rules of fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

in Kronstadt in 1539.

Individuals who did not speak German became receptive to Protestant ideas in the 1530s. Protestant preachers compared the Hungarians, suffering from Ottoman invasions, with the Jews in the Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

and Babilonian captivities, describing the Hungarians as a new chosen people, able to regain God's favor through demonstrating their faith. In contrast to this attractive explanation, Catholic clerics emphasized that the Ottoman plight had been brought to the Hungarian people as a punishment for their sins. Protestant men of letters actively participated in international scholarly networks. Many of them studied at German and Swiss universities or had direct contact to the most influential Protestant theologians.

Reformist aristocrats gave shelter to Protestant preachers in both kings' realms. Some of them entered into correspondence with Luther or Melanchthon on theological issues. A wealthy noblewoman, Katalin Frangepán, commissioned the humanist Benedek Komjáti to publish his Hungarian translation of the Epistles of St Paul

The Pauline epistles, also known as Epistles of Paul or Letters of Paul, are the thirteen books of the New Testament attributed to Paul the Apostle, although the authorship of some is in dispute. Among these epistles are some of the earliest extan ...

. The aristocrats' right of patronage over village churches, was instrumental in the insemination of Protestant ideas among the peasantry. Tamás Nádasdy

Baron Tamás Nádasdy de Nádasd et Fogarasföld (I), called the ''Great Palatine'' (1498–1562), was Hungarian nobleman, great landowner and a statesman.

Early life

Born into the House of Nádasdy, he was the son of Ferenc I Nádasdy de Ná ...

, Péter Perényi

Péter Perényi de Nagyida (died around 1423), son of Simon of the Perényi branch of the Šubić clan, was the head (or ''ispán'') of Temes County from the end of the 14th century into the start of the 15th century. He also commanded Golubac ...

and Gáspár Drágffy were among the first barons to employ Protestant pastors in their castles. János Sylvester

János Sylvester sometimes known as János Erdősi (1504–1552) was a 16th-century Hungarian figure of the Reformation, and also a poet and grammarian, who was the first to translate the New Testament into Hungarian in 1541.

Life

He was bo ...

, a graduate from the Cracow and Wittenberg universities, completed and published his Hungarian translation of the New Testament at Sárvár—the center of the Nádasdy domains—in 1541. Nádasdy was a representative figure of religious transition. He employed both an Evangelical chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

and a Catholic court preacher; he offered asylum to Anabaptist refugees, but gave donations to the Paulician monks; he corresponded both with Melanchthon and the Pope; his wife, Orsolya Kanizsai, regularly used Calvinist terminology in her correspondence with him. Protestant aristocrats ceded the village churches to the local Protestant congregations, thus transformed the originally Catholic parishes to Evangelical pastorages. Available evidence suggests that women did not preach in churches, thus the development of Protestant church structure limited the role of women in evangelization.

Most ethnic Hungarian pastors were born in market towns and this background facilitated them to address the villagers' everyday concerns. Ethnic Hungarians were exposed to reformist ideas in a period of intensive debates among concurring Protestant ideologies. Two former Franciscan friars, Mátyás Dévai Bíró and Mihály Sztárai, and Sztárai's younger co-worker, István Szegedi Kiss, represented the "theological eclecticism" of their age. Dévai Bíró came under the influence of Luther and Melanchthon around 1530, but his deep loathing of the Mass made him an ardent opponent of the doctrine of transubstantiation, for which conservative Protestants regarded him as a "Sacramentarian

The Sacramentarians were Christians during the Protestant Reformation who denied not only the Roman Catholic transubstantiation but also the Lutheran sacramental union (as well as similar doctrines such as consubstantiation).

During the turbule ...

". He was a popular pastor, serving in aristocratic courts and market towns in both kings' realms. Sztárai moved to Ottoman Hungary and established Protestant congregations in more than 120 settlements. Radical reformers attacked him for his conservative views on liturgy, but his unclear teaching on the Eucharist astonished Evangelical theologians. Szegedi Kiss was influenced by Bullinger's Eucharistic theology. His theological treaties were taught in Western European Protestant universities.

Legalization

Evangelical Church

Bishop of Transylvania

:''There is also a Romanian Orthodox Archbishop of Alba Iulia and a Greek Catholic Archdiocese of Făgăraş and Alba Iulia.''

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia ( hu, Gyulafehérvári Római Katolikus Érsekség) is a Latin Church Cath ...

, János Statileo

János Statileo, also known as John Statilius (died in 1542), was the Roman Catholic bishop of Transylvania in the Kingdom of Hungary from 1534 to 1542. He took care of the education of his orphaned nephew, Antun Vrančić—the future archbishop ...

, died in 1542. The bishopric was left vacant, its revenues were confiscated and Queen Isabella established the new royal court at the bishops' castle in Gyulafehérvár ( Alba Iulia, Romania). The Queen appointed vicars to administer the bishopric, but the vacancy left the Transylvanian Catholics without a potent leadership. After the Ottomans captured Esztergom in 1543, the archbishopric's see was transferred to Nagyszombat (Trnava

Trnava (, german: Tyrnau; hu, Nagyszombat, also known by other alternative names) is a city in western Slovakia, to the northeast of Bratislava, on the Trnávka river. It is the capital of a ''kraj'' (Trnava Region) and of an '' okres'' (Trna ...

, Slovakia) in Royal Hungary.

Evangelical divine service first replaced Catholic liturgy in eastern Hungary in Kronstadt in October 1542. The Saxons of Bistritz ( Bistrița, Romania) destroyed the " idols" in their churches in late 1542, because they interpreted a Moldavian attack against the town as the sign of the wrath of God for their idolatry. George Martinuzzi wanted to bring the Saxon priests before court on charges of heresy, but moderate politicians convinced him and the Queen to hold a religious debate at the Diet in Gyulafehérvár in June 1543. The debate was undecided and the Saxon preachers left Gyulafehérvár unharmed. Johannes Honter published a small book, the ''Reformation Pamphlet'', about the transformation of church life in Kronstadt. Not unlike other reformators, Honter was convinced that the changes could not be regarded as innovations, but as steps towards the restoration of Western Christianity's ancient purity. He argued that many actually unimportant elements of Catholic church life were alien to Orthodox travellers visiting Kronstad, a flourishing commercial center on the Hungarian–Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

n border, and their frequent demands for an explanation raised doubts about fundamental Christian doctrines in uneducated people. The most senior Saxon cleric, Matthias Ramser, sent a copy of Honter's booklet to Luther, Melanchthon and Johannes Bugenhagen for a review. The three reviewers unanimously praised it for its clarity.

Experiencing the government's unwillingness to take anti-Protestant measures, the Saxon leaders concluded that religious issues could be treated as each nation's internal affairs. In April 1544, religious issues were re-considered at the Diet at Torda ( Turda, Romania) and the co-existence of the Catholic and Evangelical denominations was tacitly recognised: a decree warned travellers to respect the devotional customs of the town or village where they were staying. The Three Nations' representatives wanted to consolidate religious and the Diet prohibited further religious innovations. In November, the Saxon nation's general assembly ordered that all Saxon towns introduce Evangelical liturgy; next year, the villages were to follow suit. Evangelical Reformation spread from Kronstadt to the nearby Székely seats, primarily through the mediation of the town's Székely guards and two suburbs' Hungarian citizens. A Székely aristocrat, Pál Daczó, was the Evangelical pastors' most influential protector in Székely Land. Some Székely nobles remained devout Catholic, like the Apor family

The Apor family (different branches styled '' altorjai'' or '' zaláni'') is a family of ancient Hungarian nobility, which played a major role in Transylvanian history. It has several branches, which held different ranks over the years, includi ...

, securing the survival of Catholic enclaves. The Saxon magistrates supported the publication of Evangelical catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adult c ...

s in Romanian. They proposed liturgical changes, but most Romanian Orthodox priests

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

rejected them. Gáspár Drágffy's widow, Anna Báthory, convened northern Partium's Hungarian pastors to a synod in Erdőd (Ardud

Ardud ( hu, Erdőd, Hungarian pronunciation: ; german: Erdeed) is a town situated in Satu Mare County, Transylvania, Romania. It administers five villages: Ardud-Vii (), Baba Novac (), Gerăușa (), Mădăras () and Sărătura ().

History

It has ...

, Romania). They adopted twelve articles based on the Augsburg Confession in September 1545.

The spread of Calvinist theology and radical ideas disturbed both the Catholic and Evangelical aristocrats and magistrates. In 1548, the eastern Hungarian Diet repeated the ban on religious innovations, while the Diet of Royal Hungary outlawed the "Sacramentarians" and Anabaptists. At the latter Diet, the royal free boroughs were blamed for lenience with radical preachers. The Catholic bishops set up commissions to expel all Protestants from Royal Hungary, but the royal free boroughs' immunities prevented the commissioners from launching investigations within their walls. Knowing that King Ferdinand had practically legalized the Augsburg Confession at the 1530 Imperial Diet, the Evangelical communities compiled confessions of faith to demonstrate their congregations' full compliance with it. A schoolmaster from Bartfeld, Leonard Stöckel, completed the first such document in September 1549. His sharply criticized "sacramentarian" and radical theologies. It was adopted by five Upper Hungarian royal free boroughs.

The Ottomans were indifferent to Christian theological debates and reformist ideas spread undisturbed in Ottoman Hungary. As the Ottoman authorities wanted to pacify the conquered territory, they were keen to maintain religious peace. They regulated the local Christian communities' religious issues in "letters of approval". They did not disturb the Christians' church life, but the construction and restoration of churches was strictly controlled and the priests could not assemble to a synod without a special permission. According to contemporaneous reports, Ottoman officials favored Protestant pastors to Catholic clergy, with some of them going as far as attending Protestant church services. In contrast, a Reformed pastor serving at Tolna, Pál Thúri Farkas, noted that Ottoman officials regularly investigated the local Christians' views about the Islamic prophet, Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

, and the Christians could avoid punishment only if they pretended ignorance. The wealthy Fuggers' representative in Hungary, Hans Dernschwam, noted in 1554 that the poor Hungarians living in Buda "had no comfort other than the Word of God, which the Lutherans preach more openly than the Papists."

The eastern Hungarian Diet enacted the Saxon interpretation and declared religious issues as part of each nation's internal affairs in 1550. The principle was not questioned after Queen Isabella and her son were exiled to Poland in 1551. The Diet regularly urged both Catholics and Evangelicals to receive each other "with deference and friendliness". In 1551, Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = Counties of Romania, County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Subdivisions of Romania, Status

, subdivision_name2 ...

, Romania), a free royal borough with a mixed Saxon and Hungarian population, met with no official opposition when the town council introduced the Evangelical version of Reformation. The unification of Royal Hungary and eastern Hungary under the Habsburgs' rule provoked an Ottoman invasion in 1552. The Ottomans annexed the Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of T ...

and refugees from the region increased the Hungarian-speaking citizenry in Kolozsvár. The town pastor, Gáspár Heltai

Gáspár Heltai (born as Kaspar Helth) (''c''. 1490–1574) was a Transylvanian Saxon writer and printer. His name possibly derives from the village Heltau ( hu, Nagydisznód, today Cisnădie, Romania). Despite being a German native speaker he ...

, although himself a Saxon, published a series of religious books in Hungarian, including his own ''Dialogue''—a collection of novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

s and parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, w ...

s, illustrating Luther's moral theology.

Reformed Church

The aristocrats' willingness to expand their privileges and Ottoman expansion created favorable circumstances for the reception of Calvinist theology. Nobles started to regard the right to choose between concurring Christian denominations as an important element of their liberties. Bullinger addressed his to the Hungarians, praising them for their struggle against the Ottomans. His work gained popularity, facilitating the spread of his theological views. Tensions between concurring Protestant ideologies intensified and public theological debates were regularly held. That a congregation dismissed a pastor who had lost a debate was not uncommon, while a charismatic pastor could convince his flock to adhere to a new theology. An experienced debater,

An experienced debater, Márton Kálmáncsehi

Márton Kálmáncsehi Sánta, also known as Martin Kálmáncsehi (; Kálmáncsa, 1500 – Debrecen, December 1550), was the first pastor to publicly preach Calvinism, Calvinist ideas in Hungary (in the 1540s). He began his church career as a Canon ...

, was installed as the town pastor of Partium's wealthy market town, Debrecen

Debrecen ( , is Hungary's second-largest city, after Budapest, the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar County. A city with county rights, it was the largest Hungarian city in the 18th century and i ...

, in 1551. He had already been famed for his passionate sermons that outraged moderate Protestants. Rumour had it that he had baptized children with water from a trough for swine to illustrate what Christian freedom meant. As town pastor, he replaced the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...