Redeemers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the

In the 1870s, Democrats began to muster more political power, as former Confederate Whites began to vote again. It was a movement that gathered energy up until the

In the 1870s, Democrats began to muster more political power, as former Confederate Whites began to vote again. It was a movement that gathered energy up until the

Online text by African American member of the United States Congress during Reconstruction era.

{{Reconstruction era 1870s establishments in the United States 1910 disestablishments in the United States Reconstruction Era American Civil War political groups History of civil rights in the United States History of the Southern United States Conservatism in the United States History of the Democratic Party (United States) Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Civil service reform in the United States Neo-Confederate organizations

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. They sought to regain their political power and enforce white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

. Their policy of Redemption was intended to oust the Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

s, a coalition of freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, " carpetbaggers", and " scalawags". They generally were led by the White yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

ry and they dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910.

During Reconstruction, the South was under occupation by federal forces, and Southern state governments were dominated by Republicans, elected largely by freedmen and allies. Republicans nationally pressed for the granting of political rights to the newly-freed slaves as the key to their becoming full citizens and the votes they would cast for the party. The Thirteenth Amendment (banning slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

), Fourteenth Amendment (guaranteeing the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

of former slaves and ensuring equal protection of the laws), and Fifteenth Amendment (prohibiting the denial of the right to vote on grounds of race, color, or previous condition of servitude), enshrined such political rights in the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

.

Numerous educated blacks moved to the South to work for Reconstruction. Some were elected to office in the Southern states, or were appointed to certain positions. The Reconstruction governments were unpopular with many White Southerners, who were not willing to accept defeat and continued to try to prevent black political activity by any means. While the elite planter class

The planter class, known alternatively in the United States as the Southern aristocracy, was a racial and socioeconomic caste of pan-American society that dominated 17th and 18th century agricultural markets. The Atlantic slave trade permitted ...

often supported insurgencies, violence against freedmen and other Republicans was usually carried out by other whites; the secret Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

chapters developed in the first years after the war as one form of insurgency.

In the 1870s, paramilitary organizations

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

, such as the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorism, terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party (United States), ...

in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

and Red Shirts in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Mis ...

and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

, undermined the Republicans, disrupting meetings and political gatherings. These paramilitary bands also used violence and threats of violence to undermine the Republican vote. By the presidential election of 1876

The following elections occurred in the year 1876.

Europe

* 1876 Dalmatian parliamentary election

* 1876 French legislative election

* 1876 Leominster by-election

* 1876 Spanish general election

North America Canada

* 1876 Prince Edward Isla ...

, only three Southern states – Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

, South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = "Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = G ...

, and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

– were "unredeemed", or not yet taken over by white Democrats. The disputed Presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes (the Republican governor of Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

) and Samuel J. Tilden (the Democratic governor of New York) was allegedly resolved by the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

, also known as the Corrupt Bargain or the Bargain of 1877. In this compromise, it was claimed, Hayes became president in exchange for numerous favors to the South, one of which was the removal of Federal troops from the remaining "unredeemed" Southern states; this was however a policy Hayes had endorsed during his campaign. With the removal of these forces, Reconstruction came to an end.

History

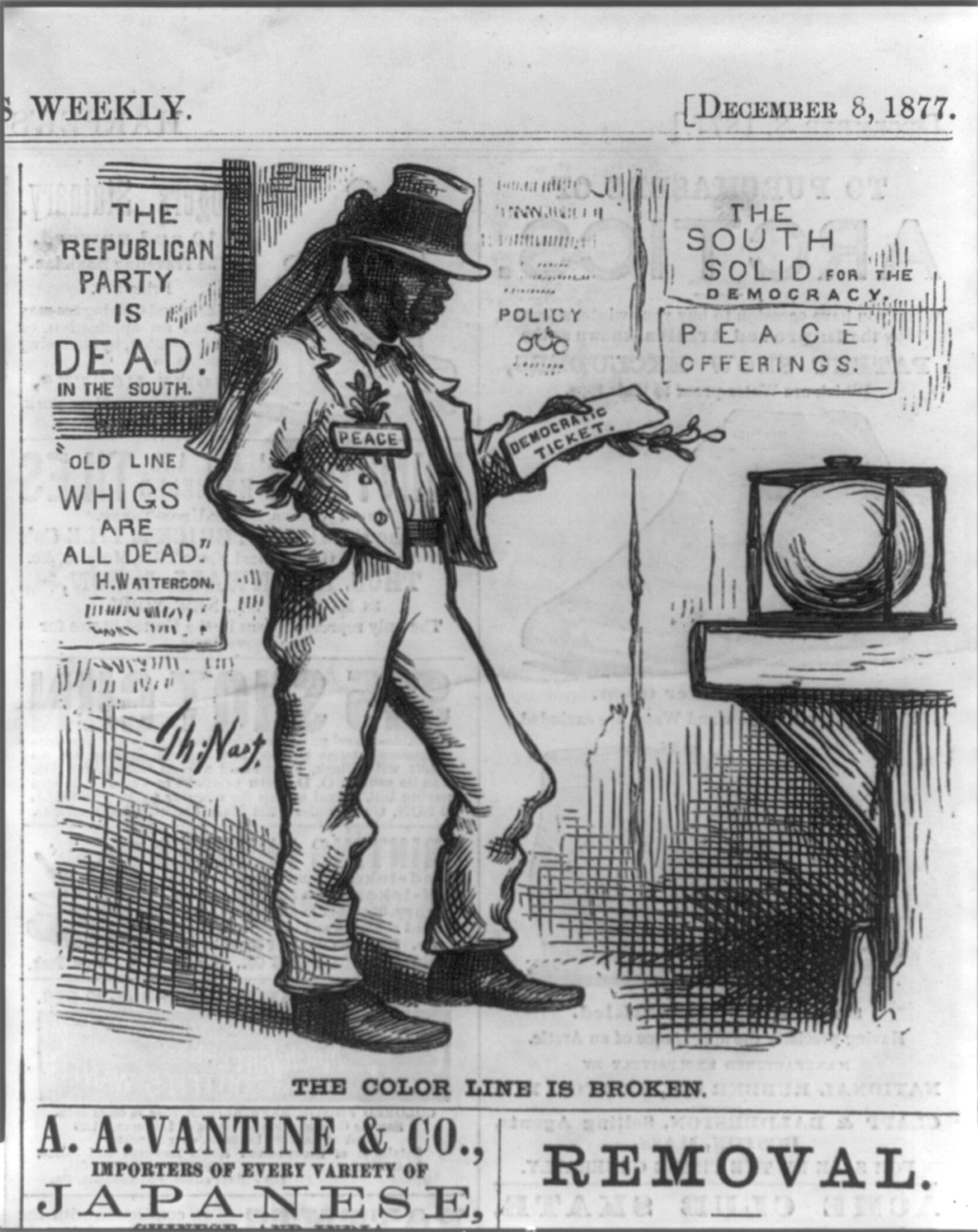

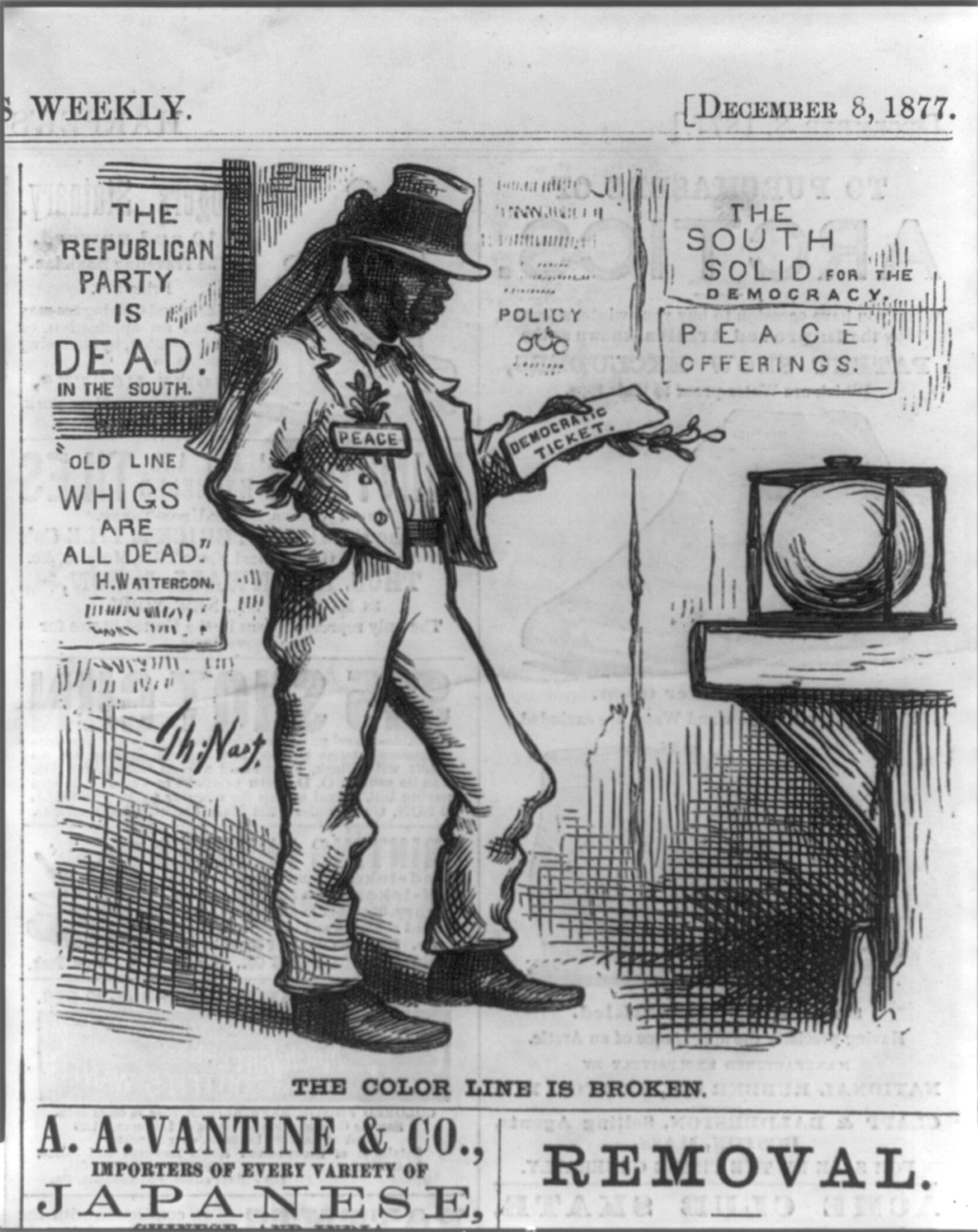

In the 1870s, Democrats began to muster more political power, as former Confederate Whites began to vote again. It was a movement that gathered energy up until the

In the 1870s, Democrats began to muster more political power, as former Confederate Whites began to vote again. It was a movement that gathered energy up until the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

, in the process known as the Redemption. White Democratic Southerners saw themselves as redeeming the South by regaining power.

More importantly, in a second wave of violence following the suppression of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

, violence began to increase in the Deep South. In 1868 White terrorists tried to prevent Republicans from winning the fall election in Louisiana. Over a few days, they killed some two hundred freedmen in St. Landry Parish in the Opelousas massacre. Other violence erupted. From April to October, there were 1,081 political murders in Louisiana, in which most of the victims were freedmen. Violence was part of campaigns prior to the election of 1872 in several states. In 1874 and 1875, more formal paramilitary groups affiliated with the Democratic Party conducted intimidation, terrorism and violence against black voters and their allies to reduce Republican voting and turn officeholders out. These included the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorism, terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party (United States), ...

and Red Shirts. They worked openly for specific political ends, and often solicited coverage of their activities by the press. Every election from 1868 on was surrounded by intimidation and violence; they were usually marked by fraud as well.

In the aftermath of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872 in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

, for instance, the competing governors each certified slates of local officers. This situation contributed to the Colfax Massacre of 1873, in which white Democratic militia killed more than 100 Republican blacks in a confrontation over control of parish offices. Three whites died in the violence.

In 1874 remnants of White militia formed the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorism, terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party (United States), ...

, a Democratic paramilitary group originating in Grant Parish of the Red River area of Louisiana, with chapters arising across the state, especially in rural areas. In August the White League turned out six Republican office holders in Coushatta, Louisiana, and told them to leave the state. Before they could make their way, they and five to twenty black witnesses were assassinated by White paramilitary. In September, thousands of armed white militia, supporters of the Democratic gubernatorial candidate John McEnery

John McEnery (1 November 1943 – 12 April 2019) was an English actor and writer.

Born in Birmingham, he trained (1962–1964) at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, playing, among others, Mosca in Ben Jonson's '' Volpone'' and Gavest ...

, fought against New Orleans police and state militia in what was called the Battle of Liberty Place

The Battle of Liberty Place, or Battle of Canal Street, was an attempted insurrection and coup d'etat by the Crescent City White League against the Reconstruction Era Louisiana Republican state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orle ...

. They took over the state government offices in New Orleans and occupied the capitol and armory. They turned Republican governor William Pitt Kellogg out of office, and retreated only in the face of the arrival of Federal troops sent by President Ulysses S. Grant.

Similarly, in Mississippi, the Red Shirts formed as a prominent paramilitary group that enforced Democratic voting by intimidation and murder. Chapters of paramilitary Red Shirts arose and were active in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

and South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = "Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = G ...

as well. They disrupted Republican meetings, killed leaders and officeholders, intimidated voters at the polls, or kept them away altogether.

The Redeemers' program emphasized opposition to the Republican governments, which they considered to be corrupt and a violation of true republican principles. The crippling national economic problems and reliance on cotton meant that the South was struggling financially. Redeemers denounced taxes higher than what they had known before the war. At that time, however, the states had few functions, and planters maintained private institutions only. Redeemers wanted to reduce state debts. Once in power, they typically cut government spending; shortened legislative sessions; lowered politicians' salaries; scaled back public aid to railroads and corporations; and reduced support for the new systems of public education and some welfare institutions.

As Democrats took over state legislatures, they worked to change voter registration rules to strip most blacks and many poor whites of their ability to vote. Blacks continued to vote in significant numbers well into the 1880s, with many winning local offices. Black Congressmen continued to be elected, albeit in ever smaller numbers, until the 1890s. George Henry White

George Henry White (December 18, 1852 – December 28, 1918) was an American attorney and politician, elected as a Republican U.S. Congressman from North Carolina's 2nd congressional district between 1897 and 1901. He later became a banker ...

, the last Southern black of the post-Reconstruction period to serve in Congress, retired in 1901, leaving Congress completely white until 1929.

In the 1890s, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

defeated the Southern Bourbon Democrats and took control of the Democratic Party nationwide. The Democrats also faced challenges with the Agrarian Revolt, when their control of the South was threatened by the Farmers Alliance, the effects of Bimetallism, and the newly created People's Party.

Disenfranchising

Democrats worked hard to prevent populist coalitions. In the former Confederate South, from 1890 to 1908, starting with Mississippi, legislatures of ten of the eleven states passed disenfranchising constitutions, which had new provisions for poll taxes,literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered ...

s, residency requirements and other devices that effectively disenfranchised nearly all blacks and tens of thousands of poor Whites. Hundreds of thousands of people were removed from voter registration rolls soon after these provisions were implemented.

In Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, for instance, in 1900 fourteen Black Belt

Black Belt may refer to:

Martial arts

* Black belt (martial arts), an indication of attainment of expertise in martial arts

* ''Black Belt'' (magazine), a magazine covering martial arts news, technique, and notable individuals

Places

* Black B ...

counties had a total of 79,311 voters on the rolls; by June 1, 1903, after the new constitution was passed, registration had dropped to just 1,081. Statewide Alabama in 1900 had 181,315 blacks eligible to vote, but by 1903 only 2,980 were registered, although at least 74,000 were literate. From 1900 to 1903, the number of White registered voters fell by more than 40,000, although the white population grew overall.

By 1941, more poor Whites than blacks had been disenfranchised in Alabama, mostly due to effects of the cumulative poll tax; estimates were that 600,000 Whites and 500,000 blacks had been disenfranchised.Glenn Feldman, ''The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama'', Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, p. 136.

In addition to being disenfranchised, African Americans and poor Whites were shut out of the political process as Southern legislatures passed Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

imposing segregation in public facilities and places. The discrimination, segregation, and disenfranchisement lasted well into the later decades of the 20th century. Those who could not vote were also ineligible to run for office or serve on juries, so they were shut out of all offices at the local and state as well as federal levels.

While Congress had actively intervened for more than 20 years in elections in the South which the House Elections Committee

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

judged to be flawed, after 1896, it backed off from intervening. Many Northern legislators were outraged about the disenfranchisement of blacks and some proposed reducing Southern representation in Congress, but they never managed to accomplish this, as Southern representatives formed a strong one-party voting bloc for decades.

Although educated African Americans mounted legal challenges (with many secretly funded by educator Booker T. Washington and his northern allies), the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

upheld Mississippi's and Alabama's provisions in its rulings in '' Williams v. Mississippi'' (1898) and ''Giles v. Harris

''Giles v. Harris'', 189 U.S. 475 (1903), was an early 20th-century United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld a state constitution's requirements for voter registration and qualifications. Although the plaintiff accused the state o ...

'' (1903).

Religious dimension

People in the movement chose the term "Redemption" from Christian theology. Historian Daniel W. StowellBlum and Poole (2005). concludes that White Southerners appropriated the term to describe the political transformation they desired, that is, the end of Reconstruction. This term helped unify numerous White voters, and encompassed efforts to purge southern society of its sins and to remove Republican political leaders. It also represented the birth of a new Southern society, rather than a return to its antebellum predecessor. Historian Gaines M. Foster explains how the South became known as the "Bible Belt

The Bible Belt is a region of the Southern United States in which socially conservative Protestant Christianity plays a strong role in society and politics, and church attendance across the denominations is generally higher than the nation's av ...

" by connecting this characterization with changing attitudes caused by slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

's demise. Freed from preoccupation with federal intervention over slavery, and even citing it as precedent, White Southerners joined Northerners in the national crusade to legislate morality. Viewed by some as a "bulwark of morality", the largely Protestant South took on a Bible Belt identity long before H. L. Mencken coined the term.

The "redeemed" South

When Reconstruction died, so did all hope for national enforcement of adherence to the constitutional amendments that the U.S. Congress had passed in the wake of theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

. As the last Federal troops left the ex-Confederacy, two old foes of American politics reappeared at the heart of the Southern polity – the twin, inflammatory issues of state rights and race. It was precisely on the ground of these two issues that the Civil War had broken out, and in 1877, sixteen years after the secession crisis, the South reaffirmed control over them.

"The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery", wrote W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

. The black community in the South was brought back under the yoke of the Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats with ...

, who had been politically undermined during Reconstruction. Whites in the South were committed to reestablish its own sociopolitical structure with the goal of a new social order enforcing racial subordination and labor control. While the Republicans succeeded in maintaining some power in part of the Upper South, such as Tennessee, in the Deep South there was a return to "home rule". Nowhere was this more true than Georgia, where an unbroken line of Democrats occupied the governor's office for 131 years, a period of dominance that only came to an end in 2003.

In the aftermath of the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

, Southern Democrats held the South's black community under increasingly tight control. Politically, blacks were gradually evicted from public office, as the few that remained saw the sway they held over local politics considerably decreased. Socially, the situation was worse, as the Southern Democrats tightened their grip on the labor force. Vagrancy

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, tem ...

and "anti-enticement" laws were reinstituted. It became illegal to be jobless, or to leave a job before the required contract expired. Economically, the blacks were stripped of independence, as new laws gave White planters the control over credit lines and property. Effectively, the black community was placed under a three-fold subjugation that was reminiscent of slavery.

Also, historian Edward L. Ayers argues that after 1877 the Redeemers were sharply divided and fought for control of the Democratic Party:

:For the next few years the Democrats seemed in control of the South, but even then deep challenges were building beneath the surface. Behind their show of unity, the Democratic Redeemers suffered deep divisions. Conflicts between upcountry and Black Belt, between town and country, and between former Democrats and former Whigs divided the Redeemers. The Democratic party proved too small to contain the ambitions of all the white men who sought its rewards, too large and unwieldy to move decisively.

Historiography

In the years immediately following Reconstruction, most blacks and former abolitionists held that Reconstruction lost the struggle forcivil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

for black people because of violence against blacks and against white Republicans. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

and Reconstruction Congressman John R. Lynch cited the withdrawal of federal troops from the South as a primary reason for the loss of voting rights and other civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

by African Americans after 1877.

But by the turn of the 20th century, white historians, led by the Dunning School, saw Reconstruction as a failure because of its political and financial corruption, its failure to heal the hatreds of the war, and its control by self-serving Northern politicians, such as those around President Grant. Historian Claude Bowers

Claude Gernade Bowers (November 20, 1878 – January 21, 1958) was a newspaper columnist and editor, author of best-selling books on American history, Democratic Party politician, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's ambassador to Spain (1933� ...

said that the worst part of what he called "the Tragic Era" was the extension of voting rights to freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, a policy he claimed led to misgovernment and corruption. The freedmen, the Dunning School historians argues, were not at fault because they were manipulated by corrupt white carpetbaggers interested only in raiding the state treasury and staying in power. They agreed the South had to be "redeemed" by foes of corruption. Reconstruction, in short, was said to violate the values of "republicanism" and all Republicans were classified as "extremists". This interpretation of events, the hallmark of the Dunning School, dominated most U.S. history textbooks from 1900 to the 1960s.

Beginning in the 1930s, historians such as C. Vann Woodward

Comer Vann Woodward (November 13, 1908 – December 17, 1999) was an American historian who focused primarily on the American South and race relations. He was long a supporter of the approach of Charles A. Beard, stressing the influence of un ...

and Howard K. Beale attacked the "redemptionist" interpretation of Reconstruction, calling themselves "revisionists" and claiming that the real issues were economic. The Northern Radicals were tools of the railroads, and the Republicans in the South were manipulated to do their bidding. The Redeemers, furthermore, were also tools of the railroads and were themselves corrupt.

In 1935, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

published a Marxist analysis in his '' Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880''. His book emphasized the role of African Americans during Reconstruction, noted their collaboration with whites, their lack of majority in most legislatures, and also the achievements of Reconstruction: establishing universal public education, improving prisons, establishing orphanages and other charitable institutions, and trying to improve state funding for the welfare of all citizens. He also noted that despite complaints, most Southern states kept the constitutions of Reconstruction for many years, some for a quarter of a century.

By the 1960s, neo-abolitionist historians led by Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner focused on the struggle of freedmen. While acknowledging corruption in the Reconstruction era, they hold that the Dunning School over-emphasized it while ignoring the worst violations of republican principles — namely denying African Americans their civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

, including their right to vote.

Supreme Court challenges

Although African Americans mounted legal challenges, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Mississippi's and Alabama's provisions in its rulings in '' Williams v. Mississippi'' (1898), ''Giles v. Harris

''Giles v. Harris'', 189 U.S. 475 (1903), was an early 20th-century United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld a state constitution's requirements for voter registration and qualifications. Although the plaintiff accused the state o ...

'' (1903), and ''Giles v. Teasley

Giles may refer to:

People

* Giles (given name), male given name (Latin: ''Aegidius'')

* Giles (surname), family name

* Saint Giles (650–710), 7th–8th-century Christian hermit saint

* Giles of Assisi, Aegidius of Assisi, 13th-century com ...

'' (1904). Booker T. Washington secretly helped fund and arrange representation for such legal challenges, raising money from northern patrons who helped support Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was ...

.

When white primaries were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in '' Smith v. Allwright'' (1944), civil rights organizations rushed to register African-American voters. By 1947 the All-Citizens Registration Committee (ACRC) of Atlanta managed to get 125,000 voters registered in Georgia, raising black participation to 18.8% of those eligible. This was a major increase from the 20,000 on the rolls who had managed to get through administrative barriers in 1940.Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, ''Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act'', Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 70.

However, Georgia, among other Southern states, passed new legislation (1958) to once again repress black voter registration. It was not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dw ...

, the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration req ...

, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

that the descendants of those who were first granted suffrage by the Fifteenth Amendment finally regained the ability to vote.

See also

*Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

* Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era

Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era in the United States, especially in the Southern United States, was based on a series of laws, new constitutions, and practices in the South that were deliberately used to prevent black citizens from ...

* Nadir of American race relations

* Phoenix Election Riot, in South Carolina

* White backlash

Notes

References

Secondary sources

* Ayers, Edward L. ''The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction'' (1993). * Baggett, James Alex. ''The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction'' (2003), a statistical study of 732 Scalawags and 666 Redeemers. * Blum, Edward J., and W. Scott Poole, eds. ''Vale of Tears: New Essays on Religion and Reconstruction''.Mercer University Press

Mercer University Press, established in 1979, is a university press operated by Mercer University. The press has published more than 1,600 books, releasing 35-40 titles annually with a 5-person staff.

Mercer is the only Baptist-related insti ...

, 2005. .

* Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. ''Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880'' (1935), explores the role of African Americans during Reconstruction

* Foner, Eric. ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877'' (2002).

* Garner, James Wilford. ''Reconstruction in Mississippi'' (1901), a classic Dunning School text.

* Gillette, William. ''Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869–1879'' (1979).

* Going, Allen J. "Alabama Bourbonism and Populism Revisited." '' Alabama Review'' 1983 36 (2): 83–109. .

* Hart, Roger L. ''Redeemers, Bourbons, and Populists: Tennessee, 1870–1896''. LSU Press

The Louisiana State University Press (LSU Press) is a university press at Louisiana State University. Founded in 1935, it publishes works of scholarship as well as general interest books. LSU Press is a member of the Association of American Uni ...

, 1975.

* Jones, Robert R. "James L. Kemper and the Virginia Redeemers Face the Race Question: A Reconsideration". '' Journal of Southern History'', 1972 38 (3): 393–414. .

* King, Ronald F. "A Most Corrupt Election: Louisiana in 1876." ''Studies in American Political Development

Studies in American Political Development (SAPD) is a political science journal founded in 1986 and presently published by Cambridge University Press. It is the flagship journal of the American political development (APD) subfield in political sc ...

'', 2001 15(2): 123–137. .

* King, Ronald F. "Counting the Votes: South Carolina's Stolen Election of 1876." '' Journal of Interdisciplinary History'' 2001 32 (2): 169–191. .

* Moore, James Tice. "Redeemers Reconsidered: Change and Continuity in the Democratic South, 1870–1900" in the ''Journal of Southern History'', Vol. 44, No. 3 (August 1978), pp. 357–378.

* Moore, James Tice. "Origins of the Solid South: Redeemer Democrats and the Popular Will, 1870–1900." ''Southern Studies'', 1983 22 (3): 285–301. .

* Perman, Michael. ''The Road to Redemption: Southern Politics, 1869-1879''. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1984. .

* Perman, Michael. "Counter Reconstruction: The Role of Violence in Southern Redemption", in Eric Anderson and Alfred A. Moss, Jr, eds. ''The Facts of Reconstruction'' (1991) pp. 121–140.

* Pildes, Richard H. "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", ''Constitutional Commentary'', 17, (2000).

* Polakoff, Keith I. ''The Politics of Inertia: The Election of 1876 and the End of Reconstruction'' (1973).

* Rabonowitz, Howard K. ''Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865-1890'' (1977).

* Richardon, Heather Cox. ''The Death of Reconstruction'' (2001).

* Wallenstein, Peter. ''From Slave South to New South: Public Policy in Nineteenth-Century Georgia'' (1987).

* Wiggins; Sarah Woolfolk. ''The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865—1881'' (1991).

* Williamson, Edward C. ''Florida Politics in the Gilded Age, 1877–1893'' (1976).

* Woodward, C. Vann. ''Origins of the New South, 1877–1913'' (1951); emphasizes economic conflict between rich and poor.

Primary sources

* Fleming, Walter L. ''Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial'' (1906), several hundred primary documents from all viewpoints * Hyman, Harold M., ed. ''The Radical Republicans and Reconstruction, 1861–1870'' (1967), collection of longer speeches by Radical leaders * Lynch, John R. ''The Facts of Reconstruction''(1913)Online text by African American member of the United States Congress during Reconstruction era.

{{Reconstruction era 1870s establishments in the United States 1910 disestablishments in the United States Reconstruction Era American Civil War political groups History of civil rights in the United States History of the Southern United States Conservatism in the United States History of the Democratic Party (United States) Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Civil service reform in the United States Neo-Confederate organizations