Rebellion Of 1798 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1798; Ulster-Scots: ''The Hurries'') was a major uprising against

From 1778 onwards a number of local militias known as the

From 1778 onwards a number of local militias known as the

Since the early 18th century, the remains of the Catholic landowning class, once strongly Jacobite, had protected their position by adopting an "obsequious" attitude to the regime, cultivating the favour of the Hanoverian monarchs directly rather than that of a hostile Irish Parliament. The death of the

Since the early 18th century, the remains of the Catholic landowning class, once strongly Jacobite, had protected their position by adopting an "obsequious" attitude to the regime, cultivating the favour of the Hanoverian monarchs directly rather than that of a hostile Irish Parliament. The death of the

While Neilson, Drennan and the other Belfast radicals were Presbyterian, a second club set up the following month in

While Neilson, Drennan and the other Belfast radicals were Presbyterian, a second club set up the following month in

Tone had arrived in France without either instructions or accreditation from the United Irishmen, but almost single-handedly convinced the French Directory to alter its policy. His written "memorials" on the situation in Ireland came to the attention of Director

Tone had arrived in France without either instructions or accreditation from the United Irishmen, but almost single-handedly convinced the French Directory to alter its policy. His written "memorials" on the situation in Ireland came to the attention of Director

By 1797 reports began to reach Britain that a secret revolutionary army was being prepared in Ireland by Tone's associates. Naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore suggested that French-inspired agitators were trying to spread the revolution to England; the crisis however appeared to pass, and in October the Navy defeated an invasion fleet of France's client state, the

By 1797 reports began to reach Britain that a secret revolutionary army was being prepared in Ireland by Tone's associates. Naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore suggested that French-inspired agitators were trying to spread the revolution to England; the crisis however appeared to pass, and in October the Navy defeated an invasion fleet of France's client state, the

In

In

On 22 August, nearly two months after the main uprisings had been defeated, about 1,000 French soldiers under

On 22 August, nearly two months after the main uprisings had been defeated, about 1,000 French soldiers under

Small fragments of the great rebel armies of the Summer of 1798 survived for a number of years and waged a form of guerrilla or "

Small fragments of the great rebel armies of the Summer of 1798 survived for a number of years and waged a form of guerrilla or "

The intimate nature of the conflict meant that the rebellion at times took on the worst characteristics of a civil war, especially in Leinster. Catholic resentment was fuelled by the remaining Penal Laws still in force. Rumours of planned massacres by both sides were common in the days before the rising and led to a widespread climate of fear across the nation.

The intimate nature of the conflict meant that the rebellion at times took on the worst characteristics of a civil war, especially in Leinster. Catholic resentment was fuelled by the remaining Penal Laws still in force. Rumours of planned massacres by both sides were common in the days before the rising and led to a widespread climate of fear across the nation.

Contemporary estimates put the death toll from 20,000 (

Contemporary estimates put the death toll from 20,000 (

online

* Smyth, James. ''The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the late 18th century''. (Macmillan, 1992). * Todd, Janet M. ''Rebel daughters: Ireland in conflict 1798'' (Viking, 2003). * Whelan, Kevin. ''The Tree of Liberty: Radicals, Catholicism and the Construction of Irish Identity, 1760–1830''. (Cork University Press, 1996). * (attrib.) * Zimmermann, Georges Denis. ''Songs of Irish rebellion: Irish political street ballads and rebel songs, 1780–1900'' (Four Courts Press, 2002).

National 1798 Centre

– Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford

The 1798 Irish Rebellion

– BBC History

– Clare library

– Irish anarchist analysis

General Joseph Holt of the 1798 Rebellion in Wicklow

Fugitive Warfare – 1798 in North Kildare

Map of Dublin 1798

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Irish Rebellion Of 1798

British rule in Ireland

British rule in Ireland spanned several centuries and involved British control of parts, or entirety, of the island of Ireland. British involvement in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained indepen ...

. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, ...

, a republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

revolutionary group influenced by the ideas of the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

and French revolutions: originally formed by Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

radicals angry at being shut out of power by the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

establishment, they were joined by many from the majority Catholic population.

Following some initial successes, particularly in County Wexford

County Wexford ( ga, Contae Loch Garman) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was based on the historic Gaelic territory of Hy Kinsella (''Uí Ceinns ...

, the uprising was suppressed by government militia and yeomanry forces, reinforced by units of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, with a civilian and combatant death toll estimated between 10,000 and 50,000. A French expeditionary force landed in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the Taxus baccata, yew trees") is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Conn ...

in August in support of the rebels: despite victory at Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Developing around a 13th century castle of the de Barry family, de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal poi ...

, they were also eventually defeated. The aftermath of the Rebellion led to the passing of the Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Irela ...

, merging the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two chamb ...

into the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

.

Despite its rapid suppression, the 1798 Rebellion remains a significant event in Irish history. Centenary celebrations in 1898

were instrumental in the development of modern Irish nationalism, while several of the Rebellion's key figures, such as Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican socie ...

, became important reference points for later republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

. Debates over the significance of 1798, the motivation and ideology of its participants, and acts committed during the Rebellion continue to the present day.

Background

Since 1691 and the end of theWilliamite War

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called th ...

, the government of Ireland had been dominated by an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

minority establishment. Membership of the Irish Parliament became restricted to members of the established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

, who were expected to identify closely with the economic and political interests of England. The support of the Catholic gentry for the Jacobite side during the war had led to Parliament passing a series of Penal Laws, barring them from holding government or military positions and restricting Catholics' ability to purchase or inherit land. The proportion of land owned by Catholics, already reduced following earlier 17th century conflicts, continued to decline.

The effect of the Penal Laws was to destroy the political influence of the Catholic gentry, many of whom sought alternative opportunities in European militaries. The same laws, however, also discriminated against Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

and other Protestant Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

, who were increasingly important in trade and commerce and were particularly strongly represented in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

.

Demands for political reform

By the middle of the 18th century, a number of factors combined to increase demands for political reform. Despite Ireland nominally being a sovereign kingdom governed by the monarch and its own Parliament, legislation such as theDeclaratory Act 1719

An Act for the better securing the dependency of the Kingdom of Ireland on the Crown of Great Britain (6. Geo. I, c. 5) was a 1719 Act of Parliament, Act passed by the Parliament of Great Britain which declared that it had the right to pass laws fo ...

meant it, in reality, had fewer privileges and freedoms than most of Britain's North American colonies. Merchants grew increasingly frustrated by commercial restrictions favouring England at Ireland's expense, adding to the list of grievances; it was claimed that Ireland was "debarred from the common and natural benefits of trade" while still being "obliged to support a large national ..and military establishment". Financial controversies such as "Wood's halfpence

William Wood (1671–1730) was a hardware manufacturer, ironmaster, and mintmaster, notorious for receiving a contract to strike an issue of Irish coinage from 1722 to 1724. He also struck the 'Rosa Americana' coins of British America during t ...

" in 1724 and the "Money Bill Dispute" of 1753, over the appropriation of an Irish treasury surplus by the Crown, alienated sections of the Protestant professional class, leading to riots in Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

.

This developing national consciousness led some members of the "Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

" to advocate greater political autonomy from Great Britain. The movement was led by figures like Charles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas, 1613 to 28 August 1648, was a professional soldier from Essex, who served as a Cavalier, Royalist cavalry leader during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Taken prisoner at the end of the First English Civil War in March 1646, ...

, a Dublin apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is a mostly archaic term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons, and patients. The modern chemist (British English) or pharmacist (British and North Ameri ...

exiled in 1749 for promoting the so-called "patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

" cause: Lucas returned 10 years later and was elected as an MP, beginning a period of increased "patriot" influence in Parliament. Some of the "patriots" also began seeking support from the growing Catholic middle class: in 1749 George Berkeley

George Berkeley (; 12 March 168514 January 1753) – known as Bishop Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne of the Anglican Church of Ireland) – was an Anglo-Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immate ...

, Bishop of Cloyne

The Bishop of Cloyne is an episcopal title that takes its name after the small town of Cloyne in County Cork, Republic of Ireland. In the Roman Catholic Church, it is a separate title; but, in the Church of Ireland, it has been united with oth ...

issued an address to the Catholic clergy, urging cooperation in the Irish national interest. In 1757 John Curry formed the Catholic Committee, which campaigned for repeal of the Penal Laws from a position of loyalty to the regime.

From 1778 onwards a number of local militias known as the

From 1778 onwards a number of local militias known as the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

were raised in response to the withdrawal of regular forces to fight in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Thousands of middle- and upper-class Anglicans, along with a few Presbyterians and Catholics, joined the Volunteers, who became central to the growing sense of a distinct Irish political identity. Although the Volunteers were formed to defend Ireland against possible French invasion, many of their members and others in the "patriot" movement became strongly influenced by American efforts to secure independence, which were widely discussed in the Irish press. Close links with recent emigrants meant that northern Presbyterians were particularly sympathetic to the Americans, who they felt were subject to the same injustices.

In 1782 the Volunteers held a Convention at Dungannon

Dungannon () is a town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is the second-largest town in the county (after Omagh) and had a population of 14,340 at the 2011 Census. The Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council had its headquarters in the ...

which demanded greater legislative independence; this heavily influenced the British executive to amend legislation restricting the Irish Parliament, confirmed by the Irish Appeals Act 1783

The Irish Appeals Act 1783 (23 Geo 3 c 28), commonly known as the Renunciation Act, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. By it the British Parliament renounced all right to legislate for Ireland, and declared that no appeal from the de ...

. With increased legislative independence secured, "Patriot" MPs such as Henry Grattan

Henry Grattan (3 July 1746 – 4 June 1820) was an Irish politician and lawyer who campaigned for legislative freedom for the Irish Parliament in the late 18th century from Britain. He was a Member of the Irish Parliament (MP) from 1775 to 18 ...

continued to press for greater enfranchisement, although the campaign quickly foundered on the issue of Catholic emancipation: although Grattan supported it, many "patriots" did not, and even the Presbyterians were "bitterly divided" on whether it should be immediate or gradual.

Against this background actual reform proceeded slowly. The Papists Act 1778

The Papists Act 1778 is an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain (18 George III c. 60) and was the first Act for Roman Catholic relief. Later in 1778 it was also enacted by the Parliament of Ireland.

Before the Act, a number of "Penal laws" ...

began to dismantle some earlier restrictions by allowing Catholics to join the army and to purchase land if they took an oath of allegiance to the Crown. In 1793 Parliament passed laws allowing Catholics meeting the property qualification to vote, but they could still neither be elected nor appointed as state officials.

Catholic opposition to the government

Since the early 18th century, the remains of the Catholic landowning class, once strongly Jacobite, had protected their position by adopting an "obsequious" attitude to the regime, cultivating the favour of the Hanoverian monarchs directly rather than that of a hostile Irish Parliament. The death of the

Since the early 18th century, the remains of the Catholic landowning class, once strongly Jacobite, had protected their position by adopting an "obsequious" attitude to the regime, cultivating the favour of the Hanoverian monarchs directly rather than that of a hostile Irish Parliament. The death of the Old Pretender

James Francis Edward Stuart (10 June 16881 January 1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender by Whigs, was the son of King James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland, and his second wife, Mary of Modena. He was Prince of Wales fro ...

in 1766, and Pope Clement XIII

Pope Clement XIII ( la, Clemens XIII; it, Clemente XIII; 7 March 1693 – 2 February 1769), born Carlo della Torre di Rezzonico, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 July 1758 to his death in February 1769. ...

's subsequent recognition of the Hanoverians, reduced government suspicions of Jacobite sympathies among Catholics. Most senior Catholic churchmen also expressed loyalty to the government, hoping to secure increased tolerance. These attitudes however "barely impinged on ..the mass of the population".

19th century historiography assumed that the rural, Catholic Ireland of the majority was largely quiet during the 18th century and unaffected by urban demands for reform. Outbreaks of rural violence by "Whiteboys

The Whiteboys ( ga, na Buachaillí Bána) were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in the ...

" from the 1760s onwards, directed against landlords and tithe proctors, were assumed by historians such as Lecky to have been driven by local, agrarian issues such as tenant farmers' rents rather than wider political consciousness.

More recently it has been argued that the persistence of Jacobite imagery among Whiteboy and other groups suggests that strong opposition to Protestant and British rule remained widespread in Gaelic-speaking rural Ireland. A further dimension was provided by a younger generation of Catholic gentry and "middlemen"

in counties like Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 N ...

, some of whom were radicalised by time spent in Revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, and who often emerged as local leaders in 1798.

Unrest had also grown in County Armagh

County Armagh (, named after its county town, Armagh) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the southern shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and ha ...

in the decade prior to the Rebellion involving clashes between groups of "Defenders

Defender(s) or The Defender(s) may refer to:

*Defense (military)

*Defense (sports)

**Defender (association football)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Defender'' (1989 film), a Canadian documentary

* ''The Defender'' (1994 f ...

", a Catholic secret society, and Protestant gangs of "Break of Day Men" or "Peep o' Day Boys

The Peep o' Day Boys was an agrarian Protestant association in 18th-century Ireland. Originally noted as being an agrarian society around 1779–80, from 1785 it became the Protestant component of the sectarian conflict that emerged in County Arm ...

". Originating as nonsectarian "fleets" of young men, the groups emerged in north Armagh in the 1780s before spreading southwards. Like "Whiteboyism" this activity is often depicted as economic in origin, triggered by competition between Protestants and Catholics in the lucrative linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

industry of the area. However, there is evidence that as time went on the Defenders developed an increasing political consciousness.

Formation of the Society of United Irishmen

The 1789French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

provided further inspiration to more radical members of the Volunteer movement, who saw it as an example of the common people cooperating to remove a corrupt regime. In early 1791, wool merchant Samuel Neilson

Samuel Neilson (17 September 1761 – 29 August 1803) was an Irish businessman, journalist and politician. He was a founding member of the Society of United Irishmen and the founder of its newspaper, the Northern Star (newspaper of the Society of ...

, a former Volunteer who had attended the Dungannon convention, made plans to set up a pro-French newspaper, the '' Northern Star''. He was joined from spring 1791 by a group from the Belfast Volunteers led by doctor William Drennan

William Drennan (23 May 1754 – 5 February 1820) was an Irish physician and writer who moved the formation in Belfast and Dublin of the Society of United Irishmen. He was the author of the Society's original "test" which, in the cause of ...

, who formed a secret political club called the "Irish Brotherhood". Inspired by events in France and the publication of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's ''Rights of Man

''Rights of Man'' (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the ...

'', they drew up a programme including the independence of Ireland on a republican model, parliamentary reform, and the restoration of all civic rights to Catholics.

While Neilson, Drennan and the other Belfast radicals were Presbyterian, a second club set up the following month in

While Neilson, Drennan and the other Belfast radicals were Presbyterian, a second club set up the following month in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

included a more representative mix of Anglicans, Presbyterians and Catholics from the city's professional classes. One member, barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

Theobald Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican socie ...

, suggested the name "Society of United Irishmen", which was adopted by the whole organisation. The Society initially took a constitutional approach, but the 1793 outbreak of war with France forced the organisation underground when Pitt's government acted to suppress the political clubs. Tone fled to America, and Drennan was arrested and charged with seditious libel; although acquitted, he took little further part in events. In response Neilson and others in the Belfast group began restructuring the United Irishmen on revolutionary lines.

In May 1795 the Belfast delegates approved a "New System" of organisation: this was based on cells or 'societies' of 20–35 men, with a tiered structure of baronial

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

, county, and provincial committees reporting to a single national committee, mirroring the structure of the Presbyterian church. In 1796 the New System was transformed into a military structure, each group of three 'societies' forming one company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

. Numbers grew rapidly; many Presbyterian shopkeepers and farmers joined in the North, while recruitment efforts among the Defenders

resulted in the admission of many new Catholic members across the country.

In the same period a group of new leaders were elected to the United "Directory" in Dublin, notably two radicals from the aristocracy, Arthur O'Connor and MP Lord Edward FitzGerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat who abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Independence, and as an Irish Parliamentarian, to embrace the caus ...

. Other members of the committee included lawyer Thomas Addis Emmet

Thomas Addis Emmet (24 April 176414 November 1827) was an Irish and American lawyer and politician. He was a senior member of the revolutionary Irish republican group United Irishmen in the 1790s. He served as Attorney General of New York from ...

, physician William McNevin, and Catholic Committee secretary Richard McCormick. To augment their growing strength, the United Irish leadership decided to seek military help from the current French revolutionary government, the Directory

Directory may refer to:

* Directory (computing), or folder, a file system structure in which to store computer files

* Directory (OpenVMS command)

* Directory service, a software application for organizing information about a computer network's u ...

. Tone travelled from the United States to France to press the case for intervention, landing at Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

in February 1796 following a stormy winter crossing.

The 1796 invasion attempt

Tone had arrived in France without either instructions or accreditation from the United Irishmen, but almost single-handedly convinced the French Directory to alter its policy. His written "memorials" on the situation in Ireland came to the attention of Director

Tone had arrived in France without either instructions or accreditation from the United Irishmen, but almost single-handedly convinced the French Directory to alter its policy. His written "memorials" on the situation in Ireland came to the attention of Director Lazare Carnot

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Count Carnot (; 13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) was a French mathematician, physicist and politician. He was known as the "Organizer of Victory" in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Education and early ...

, who, seeing an opportunity to destabilise Great Britain, asked for a formal invasion plan to be developed. By May, General Henry Clarke, head of the War Ministry's ''Bureau Topographique'', had drawn up an initial plan offering the Irish 10,000 troops and arms for 20,000 more men, with strict insistence that the United Irishmen attempt no rising until the French had landed. In June Carnot wrote to the experienced general Lazare Hoche

Louis Lazare Hoche (; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars. He won a victory over Royalist forces in Brittany. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on ...

asking him to act as commander and describing the plan as "the downfall of the most dangerous of our enemies. I see in it the safety of France for centuries to come."

A force of 15,000 veteran troops was assembled at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

under Hoche. Sailing on 16 December, accompanied by Tone, the French arrived off the coast of Ireland at Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mi ...

on 22 December 1796 after eluding the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

; however, unremitting storms, bad luck and poor seamanship all combined to prevent a landing. Tone remarked that "England ..had its luckiest escape since the Armada;" the fleet was forced to return home and the army intended to spearhead the invasion of Ireland was split up and sent to fight in other theatres of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

.

Counter-insurgency and repression

By 1797 reports began to reach Britain that a secret revolutionary army was being prepared in Ireland by Tone's associates. Naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore suggested that French-inspired agitators were trying to spread the revolution to England; the crisis however appeared to pass, and in October the Navy defeated an invasion fleet of France's client state, the

By 1797 reports began to reach Britain that a secret revolutionary army was being prepared in Ireland by Tone's associates. Naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore suggested that French-inspired agitators were trying to spread the revolution to England; the crisis however appeared to pass, and in October the Navy defeated an invasion fleet of France's client state, the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bona ...

, at Camperdown.

Tone had attempted to convince the increasingly influential general Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, who had recently mounted a successful campaign in Italy that another landing in Ireland was feasible. Bonaparte initially showed little interest: he was largely unfamiliar with the Irish situation and needed a war of conquest, not of liberation, to pay his army. However, by February 1798 British spies reported he was preparing a fleet in the Channel ports ready for the embarkation of up to 50,000 men. Their destination remained unknown, but the reports were immediately passed to the Irish government under the Viceroy, Lord Camden.

In early 1798, a series of violent attacks on magistrates in County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early 13th century, shortly after th ...

, County Kildare

County Kildare ( ga, Contae Chill Dara) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the county, ...

and King's County alarmed the authorities. They also received information that a faction of the United Irish leadership, led by Fitzgerald and O'Connor, felt they were "sufficiently well organised and equipped" to begin an insurgency without French aid; they were opposed by Emmet, McCormick and NcNevin, who favoured an approach protecting life and property and wanted to wait for a French landing. Camden came under increasing pressure from hardline Irish MPs, led by Speaker John Foster, to crack down on the disorder in the south and midlands and arrest the Dublin leadership.

Camden prevaricated for some time, partly as he feared a crackdown would itself provoke an insurrection: the British Home Secretary Lord Portland agreed, describing the proposals as "dangerous and inconvenient". The situation changed when United Irish documents on manpower were leaked by an informer, silk merchant Thomas Reynolds, suggesting nearly 280,000 men across Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

and Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

were preparing to join the "revolutionary army". The Irish government learned from Reynolds that a meeting of the Leinster "Directory" had been set for 10 March in the Dublin house of wool merchant Oliver Bond

Oliver may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and literature

Books

* ''Oliver the Western Engine'', volume 24 in ''The Railway Series'' by Rev. W. Awdry

* '' Oliver Twist'', a novel by Charles Dickens

Fictional characters

* Ariadne Oliver ...

, where a motion for an immediate rising would be voted on. Camden decided to move to arrest the leadership, arguing to London that he otherwise risked having the Irish Parliament turn against him. On the tenth, most of the moderates among the leadership such as Emmett, McNevin and Dublin City delegate Thomas Traynor were taken: several of the 'country' delegates arrived late to the meeting and escaped, as did McCormick. The only other senior member to escape was Fitzgerald himself, who went into hiding; the incident had the effect of strengthening Fitzgerald's faction and pushing the leadership towards rebellion.

The Irish government effectively imposed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

on 30 March, although civil courts continued sitting. Overall command of the army was transferred from Ralph Abercromby

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby (7 October 173428 March 1801) was a British people, British soldier and politician. He rose to the rank of lieutenant-general in the British Army, was appointed Gov ...

to Gerard Lake

Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (27 July 1744 – 20 February 1808) was a British general. He commanded British forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and later served as Commander-in-Chief of the military in British India.

Background

He was ...

, who supported an aggressive approach against suspected rebels.

A rising in Cahir

Cahir (; ) is a town in County Tipperary in Ireland. It is also a civil parish in the barony of Iffa and Offa West.

Location and access

For much of the twentieth century, Cahir stood at an intersection of two busy national roadways: the Dublin ...

, County Tipperary broke out in response, but was quickly crushed by the High Sheriff, Col. Thomas Judkin-Fitzgerald. Militants led by Samuel Neilson

Samuel Neilson (17 September 1761 – 29 August 1803) was an Irish businessman, journalist and politician. He was a founding member of the Society of United Irishmen and the founder of its newspaper, the Northern Star (newspaper of the Society of ...

and Lord Edward FitzGerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat who abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Independence, and as an Irish Parliamentarian, to embrace the caus ...

with the help of co-conspirator Edmund Gallagher dominated the rump United Irish leadership and planned to rise without French aid, fixing the date for 23 May.

Rebellion

The initial plan was to take Dublin, with the counties bordering Dublin to rise in support and prevent the arrival of reinforcements followed by the rest of the country who were to tie down other garrisons. The signal to rise was to be spread by the interception of themail coach

A mail coach is a stagecoach that is used to deliver mail. In Great Britain, Ireland, and Australia, they were built to a General Post Office-approved design operated by an independent contractor to carry long-distance mail for the Post Office. M ...

es from Dublin. However, last-minute intelligence from informants provided the Government with details of rebel assembly points in Dublin and a huge force of military occupied them barely one hour before rebels were to assemble. The Army then arrested most of the rebel leaders in the city. Deterred by the military, the gathering groups of rebels quickly dispersed, abandoning the intended rallying points, and dumping their weapons in the surrounding lanes. In addition, the plan to intercept the mail coaches miscarried, with only the Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

-bound coach halted at Johnstown, near Naas

Naas ( ; ga, Nás na Ríogh or ) is the county town of County Kildare in Ireland. In 2016, it had a population of 21,393, making it the second largest town in County Kildare after Newbridge.

History

The name of Naas has been recorded in th ...

, on the first night of the rebellion.

Although the planned nucleus of the rebellion had imploded, the surrounding districts of Dublin rose as planned and were swiftly followed by most of the counties surrounding Dublin. The first clashes of the rebellion took place just after dawn on 24 May. Fighting quickly spread throughout Leinster, with the heaviest fighting taking place in County Kildare

County Kildare ( ga, Contae Chill Dara) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the county, ...

where, despite the Army successfully beating off almost every rebel attack, the rebels gained control of much of the county as military forces in Kildare were ordered to withdraw to Naas

Naas ( ; ga, Nás na Ríogh or ) is the county town of County Kildare in Ireland. In 2016, it had a population of 21,393, making it the second largest town in County Kildare after Newbridge.

History

The name of Naas has been recorded in th ...

for fear of their isolation and destruction as at Prosperous. However, rebel defeats at Carlow

Carlow ( ; ) is the county town of County Carlow, in the south-east of Ireland, from Dublin. At the 2016 census, it had a combined urban and rural population of 24,272.

The River Barrow flows through the town and forms the historic bounda ...

and the hill of Tara

The Hill of Tara ( ga, Teamhair or ) is a hill and ancient ceremonial and burial site near Skryne in County Meath, Ireland. Tradition identifies the hill as the inauguration place and seat of the High Kings of Ireland; it also appears in Iri ...

, County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the sou ...

, effectively ended the rebellion in those counties. In County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by t ...

, news of the rising spread panic and fear among loyalists; they responded by massacring rebel suspects held in custody at Dunlavin Green

Dunlavin Green is an Irish ballad referring to the Dunlavin Green executions in 1798 of 36 suspected rebels.

Notable recordings

* 1956 – Patrick Galvin – Irish Songs of Resistance Part I

* 1975 - Gay Woods and Terry Woods - Backwoods

* ...

and in Carnew

Carnew () is a village in County Wicklow, Ireland. It is the most southerly town in Wicklow situated just a mile from the border with County Wexford. For historical reasons it has often been described as "a Protestant enclave".

Location

Car ...

. A baronet, Sir Edward Crosbie, was found guilty of leading the rebellion in Carlow and executed for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.

Spreading of the rebellion

In

In County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by t ...

, large numbers rose but chiefly engaged in a bloody rural guerrilla war with the military and loyalist forces. General Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the secession of the South. He returned to Ke ...

led up to 1,000 men in the Wicklow Mountains

The Wicklow Mountains (, archaic: ''Cualu'') form the largest continuous upland area in the Republic of Ireland. They occupy the whole centre of County Wicklow and stretch outside its borders into the counties of Dublin, Wexford and Carlow. Wh ...

and forced the British to commit substantial forces to the area until his capitulation in October.

In the north-east, mostly Presbyterian rebels led by Henry Joy McCracken

Henry Joy McCracken (31 August 1767 – 17 July 1798) was an Irish republican, a leading member of the Society of the United Irishmen and a commander of their forces in the field in the Rebellion of 1798. In pursuit of an independent and democrat ...

rose in County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population o ...

on 6 June. They briefly held most of the county, but the rising there collapsed following defeat at Antrim town

Antrim ( ga, Aontroim , meaning 'lone ridge') is a town and civil parish in County Antrim in the northeast of Northern Ireland, on the banks of the Six Mile Water, on the northeast shore of Lough Neagh. It had a population of 23,375 people in ...

. In County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, after initial success at Saintfield

Saintfield () is a village and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is about halfway between Belfast and Downpatrick on the A7 road. It had a population of 3,381 in the 2011 Census, made up mostly of commuters working in both south a ...

, rebels were defeated on the 11th at Portaferry

Portaferry () is a small town in County Down, Northern Ireland, at the southern end of the Ards Peninsula, near the Narrows at the entrance to Strangford Lough. It is home to the Exploris aquarium and is well known for the annual Gala Week Flo ...

and, led by Henry Munro, decisively in the longest battle of the rebellion at Ballynahinch Ballynahinch may refer to:

Northern Ireland

* Ballynahinch, County Armagh, a townland

*Ballynahinch, County Down, a town

Republic of Ireland

*Ballynahinch (barony), in County Galway

*Ballynahinch, County Galway, a townland in County Galway

* Bally ...

on the 12th.

The rebels had most success in the south-eastern county of Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 N ...

where forces primarily led by Fr. John Murphy seized control of the county, but a series of bloody defeats at the Battle of New Ross, Battle of Arklow

The second Battle of Arklow took place during the 1798 rebellion, Irish Rebellion of 1798 on 9 June when a force of United Irishmen from Wexford, estimated at 10,000 strong, launched an assault into County Wicklow, on the British-held town of A ...

, and the Battle of Bunclody

The battle of Bunclody or Newtownbarry as it was then called, was a battle in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which took place on 1 June 1798 when a force of some 5,000 rebels led by Catholic priest Fr. Mogue Kearns attacked the garrison at Bunclo ...

prevented the effective spread of the rebellion beyond the county borders. 20,000 troops eventually poured into Wexford and defeated the rebels at the Battle of Vinegar Hill

The Battle of Vinegar Hill (''Irish'': ''Cath Chnoc Fhíodh na gCaor'') was a military engagement during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 on 21 June 1798 between a force of approximately 13,000 government troops under the command of Gerard Lake and ...

on 21 June. The dispersed rebels spread in two columns through the midlands, Kilkenny

Kilkenny (). is a city in County Kilkenny, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region and in the province of Leinster. It is built on both banks of the River Nore. The 2016 census gave the total population of Kilkenny as 26,512.

Kilken ...

, and finally towards Ulster. The last remnants of these forces fought on until their final defeat on 14 July at the battles of Knightstown Bog, County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the sou ...

and Ballyboughal, County Dublin

"Action to match our speech"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Dublin.svg

, map_alt = map showing County Dublin as a small area of darker green on the east coast within the lighter green background of ...

.

French intervention

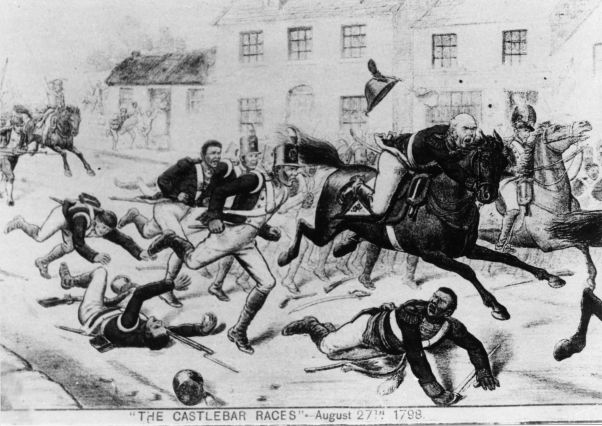

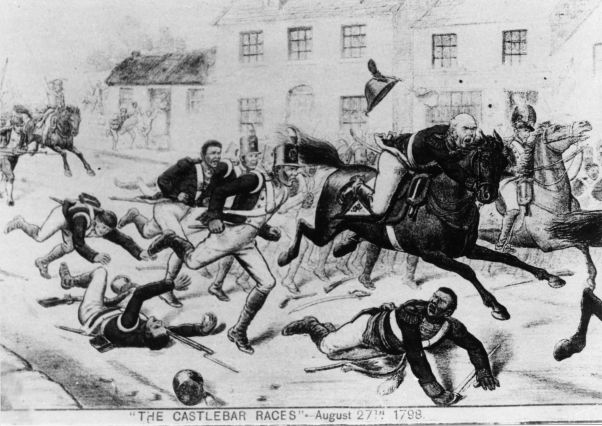

On 22 August, nearly two months after the main uprisings had been defeated, about 1,000 French soldiers under

On 22 August, nearly two months after the main uprisings had been defeated, about 1,000 French soldiers under General Humbert

General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert (22 August 1767 – 3 January 1823) was a French military officer who participated in several notable military conflicts of the late 18th and early 19th century. Born in the townland of La Coâre Saint-Nabord, ...

landed in the north-west of the country, at Kilcummin in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the Taxus baccata, yew trees") is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Conn ...

. Joined by up to 5,000 local rebels, they had some initial success, inflicting a humiliating defeat on the British in Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Developing around a 13th century castle of the de Barry family, de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal poi ...

(also known as the ''Castlebar races'' to commemorate the speed of the retreat) and setting up a short-lived "Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

" with John Moore as president of one of its provinces, Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

. This sparked some supportive uprisings in Longford and Westmeath which were quickly defeated. The Franco-Irish force won another minor engagement at the battle of Collooney

The Battle of Collooney, also called the Battle of Carricknagat, refers to a battle which occurred on 5 September during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 when a combined force of French troops and Irish rebels defeated a force of British troops outsi ...

before the main force was defeated at the battle of Ballinamuck, in County Longford

County Longford ( gle, Contae an Longfoirt) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was 46,6 ...

, on 8 September 1798. The Irish Republic had only lasted twelve days from its declaration of independence to its collapse. The French troops who surrendered were repatriated to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in exchange for British prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

, but hundreds of the captured Irish rebels were executed. This episode of the 1798 Rebellion became a major event in the heritage and collective memory of the West of Ireland and was commonly known in Irish as and in English as "The Year of the French".

Despite their general anti-clericalism and hostility to the Bourbon monarchy, the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and r ...

suggested to the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, ...

in 1798 restoring the Jacobite Pretender, Henry Benedict Stuart

Henry Benedict Thomas Edward Maria Clement Francis Xavier Stuart, Cardinal Duke of York (6 March 1725 – 13 July 1807) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, as well as the fourth and final Jacobite heir to publicly claim the thrones of Great Brit ...

, as Henry IX, King of the Irish. This was on account of General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert

General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert (22 August 1767 – 3 January 1823) was a French military officer who participated in several notable military conflicts of the late 18th and early 19th century. Born in the townland of La Coâre Saint-Nabord, ...

landing a force in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the Taxus baccata, yew trees") is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Conn ...

for the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and realising the local population were devoutly Catholic (a significant number of Irish priests supported the Rising and had met with Humbert, although Humbert's Army had been veterans of the anti-clerical campaign in Italy). The French Directory hoped this option would allow the creation of a stable French client state in Ireland, however, Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican socie ...

, the Protestant republican leader, scoffed at the suggestion and it was quashed.

On 12 October 1798, a larger French force consisting of 3,000 men, and including Wolfe Tone himself, attempted to land in County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrconne ...

near Lough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen, Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glaci ...

. They were intercepted by a larger Royal Navy squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

, and finally surrendered after a three-hour battle without ever landing in Ireland. Wolfe Tone was tried by court-martial in Dublin and found guilty. He asked for death by firing squad, but when this was refused, Tone cheated the hangman by slitting his own throat in prison on 12 November, and died a week later.

Aftermath

Small fragments of the great rebel armies of the Summer of 1798 survived for a number of years and waged a form of guerrilla or "

Small fragments of the great rebel armies of the Summer of 1798 survived for a number of years and waged a form of guerrilla or "fugitive

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

" warfare in several counties. In County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by t ...

, General Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the secession of the South. He returned to Ke ...

fought on until his negotiated surrender in Autumn 1798. It was not until the failure of Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Protes ...

's rebellion in 1803 that the last organised rebel forces under Captain Michael Dwyer

Michael Dwyer (1772–1825) was an insurgent captain in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, leading the United Irish forces in battles in Wexford and Wicklow., Following the defeat and dispersal of the rebel hosts, in July 1798 Dwyer withdrew into ...

capitulated. Small pockets of rebel resistance had also survived within Wexford and the last rebel group under James Corcoran

James Corcoran (c.1780 – 1804) was an Irish rebel leader who following the suppression of the United Irish insurrection of 1798, maintained a guerrilla resistance to the British Crown forces in counties Wexford and Kilkenny until his final ...

was not vanquished until February 1804.

The Act of Union, having been passed in August 1800, came into effect on 1 January 1801 and took away the measure of autonomy granted to Ireland's Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

. It was passed largely in response to the rebellion and was underpinned by the perception that the rebellion was provoked by the brutish misrule of the Ascendancy as much as the efforts of the United Irishmen.

Religious, if not economic, discrimination against the Catholic majority was gradually abolished after the Act of Union but not before widespread mobilisation of the Catholic population under Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

. Discontent at grievances and resentment persisted but resistance to British rule now largely manifested itself along anti-taxation lines, as in the Tithe War

The Tithe War ( ga, Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a campaign of mainly nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830 and 1836 in reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority f ...

of 1831–36.

Presbyterian radicalism was effectively tamed or reconciled to British rule by inclusion in a new Protestant Ascendancy, as opposed to a merely Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

one. By mid-1798 a schism between the Presbyterians and Catholics had developed, with radical Presbyterians starting to waver in their support for revolution.Blackstock, Alan: ''A Forgotten Army: The Irish Yeomanry''. History Ireland, Vol 4. 1996 The government capitalised on this by acting against the Catholics in the radical movement instead of the northern Presbyterians. Prior to the rebellion, anyone who admitted to being a member of the United Irishmen was expelled from the Yeomanry, however former Presbyterian radicals were now able to enlist in it, and those radicals that wavered in support saw it as their chance to reintegrate themselves into society. The government also had news of the sectarian massacre of Protestants at Scullabogue spread to increase Protestant fears and enhance the growing division. Anglican clergyman Edward Hudson claimed that "the brotherhood of affection is over", as he enlisted former radicals into his Portglenone Yeomanry corps. On 1 July 1798 in Belfast, the birthplace of the United Irishmen movement, it is claimed that everyman had the red coat of the Yeomanry on. However, the Protestant contribution to the United Irish cause was not yet entirely finished as several of the leaders of the 1803 rebellion were Anglican or Presbyterian.

Nevertheless, this fostering or resurgence of religious division meant that Irish politics was largely, until the Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political movement, political and cultural movement, cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nati ...

movement in the mid-19th century, steered away from the unifying vision of the egalitarian United Irishmen and based on sectarian fault lines with Unionist and Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the se ...

individuals at the helm of power in Ireland. After Robert Emmet's rebellion of 1803 and the Act of Union Ulster Presbyterians and other dissenters were likely bought off by British/English Anglican ruling elites with industry ship building wollen mill and as the 19th century progressed they become less and less radical and Republican/Nationalist in outlook.

Atrocities

The intimate nature of the conflict meant that the rebellion at times took on the worst characteristics of a civil war, especially in Leinster. Catholic resentment was fuelled by the remaining Penal Laws still in force. Rumours of planned massacres by both sides were common in the days before the rising and led to a widespread climate of fear across the nation.

The intimate nature of the conflict meant that the rebellion at times took on the worst characteristics of a civil war, especially in Leinster. Catholic resentment was fuelled by the remaining Penal Laws still in force. Rumours of planned massacres by both sides were common in the days before the rising and led to a widespread climate of fear across the nation.

Government

The aftermath of almost every British victory in the rising was marked by the massacre of captured and wounded rebels with some on a large scale such as at Carlow, New Ross, Ballinamuck and Killala. The British were responsible for particularly gruesome massacres at Gibbet Rath,New Ross

New Ross (, formerly ) is a town in southwest County Wexford, Ireland. It is located on the River Barrow, near the border with County Kilkenny, and is around northeast of Waterford. In 2016 it had a population of 8,040 people, making it the ...

and Enniscorthy

Enniscorthy () is the second-largest town in County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. At the 2016 census, the population of the town and environs was 11,381. The town is located on the picturesque River Slaney and in close proximity to the ...

, burning rebels alive in the latter two. For those rebels who were taken alive in the aftermath of battle, being regarded as traitors to the Crown, they were not treated as prisoners of war but were executed, usually by hanging. Local forces publicly executed suspected members of the United Irishmen without trial in Dunlavin in what is known as the Dunlavin Green executions

The Dunlavin Green executions was summary execution of 36 suspected United Irishmen rebels in County Wicklow, Ireland by the Irish Yeomanry shortly after the outbreak of the rebellion of 1798. There are several accounts of the events, reco ...

, and in Carnew

Carnew () is a village in County Wicklow, Ireland. It is the most southerly town in Wicklow situated just a mile from the border with County Wexford. For historical reasons it has often been described as "a Protestant enclave".

Location

Car ...

days after the outbreak of the rebellion.

In addition, non-combatant civilians were murdered by the military, who also carried out many instances of rape, particularly in County Wexford. Many individual instances of murder were also unofficially carried out by local Yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units or sub-units of the British Army, British Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Army Reserve, descended from volunteer British Cavalry, cavalry regiments. Today, Yeomanry units serve in a variety of ...

units before, during and after the rebellion as their local knowledge led them to attack suspected rebels. "Pardoned" rebels were a particular target.

According to the historian Guy Beiner

Guy Beiner (born in 1968 in Jerusalem) is an Israeli historian of the late-modern period. He was formerly a full professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beer Sheva, Israel. In September 2021, he was named the Sullivan Chair in Irish ...

, the Presbyterian insurgents in Ulster suffered more executions than any other arena of the 1798 rebellion, and the brutality with which the insurrection was quelled in counties Antrim and Down was long remembered in local folk traditions.

Rebel

County Wexford was the only area which saw widespread atrocities by the rebels during theWexford Rebellion

The Wexford Rebellion refers to the outbreak in County Wexford, Ireland in May 1798 of the Society of United Irishmen's rebellion against the British rule. It was the most successful and most destructive of all the uprisings that occurred throu ...

. Massacres of loyalist prisoners took place at the Vinegar Hill

Vinegar is an aqueous solution of acetic acid and trace compounds that may include flavorings. Vinegar typically contains 5–8% acetic acid by volume. Usually, the acetic acid is produced by a double fermentation, converting simple sugars to ...

camp and on Wexford bridge. After the defeat of a rebel attack at New Ross

New Ross (, formerly ) is a town in southwest County Wexford, Ireland. It is located on the River Barrow, near the border with County Kilkenny, and is around northeast of Waterford. In 2016 it had a population of 8,040 people, making it the ...

, the Scullabogue Barn massacre

The Scullabogue massacre was an atrocity committed in Scullabogue, near Newbawn, County Wexford, Ireland on 5 June 1798, during the 1798 rebellion. Rebels massacred up to 200 noncombatant men, women and children, most of whom were Protestant, ...

occurred, in which between 80 and 200Lydon, James F. ''The making of Ireland: from ancient times to the present'', pg 274 mostly Protestant men, women, and children were imprisoned in a barn which was then set alight.Dunne, Tom. ''Rebellions: Memoir, Memory and 1798''. The Lilliput Press, 2004; In Wexford town

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 ...

, on 20 June some 70 loyalist prisoners were marched to the bridge (first stripped naked, according to an unsourced claim by historian James Lydon) and piked to death.

Legacy

Contemporary estimates put the death toll from 20,000 (

Contemporary estimates put the death toll from 20,000 (Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the se ...

) to as many as 50,000 of which 2,000 were military and 1,000 loyalist civilians. Some modern research argues that these figures may be too high. Firstly, a list of British soldiers killed, compiled for a fund to aid the families of dead soldiers, listed just 530 names. Secondly, professor Louis Cullen, through an examination of depletion of the population in County Wexford between 1798 and 1820, put the fatalities in that county due to the rebellion at 6,000. Historian Thomas Bartlett therefore argues, "a death toll of 10,000 for the entire island would seem to be in order". Other modern historians believe that the death toll may be even higher than contemporary estimates suggest as the widespread fear of repression among relatives of slain rebels led to mass concealment of casualties.Marianne Elliott

Marianne Phoebe Elliott (born 27 December 1966) is a British theatre director and producer who works on the West End and Broadway. She has received numerous accolades including three Laurence Olivier Awards and four Tony Awards.

Initially ...

, "''Rebellion, a Television history of 1798''" (RTÉ 1998)

By the centenary of the Rebellion in 1898, conservative Irish nationalists and the Catholic Church would both claim that the United Irishmen had been fighting for "Faith and Fatherland", and this version of events is still, to some extent, the lasting popular memory of the rebellion. A series of popular "98 Clubs" were formed. At the bicentenary in 1998, the non-sectarian and democratic ideals of the Rebellion were emphasised in official commemorations, reflecting the desire for reconciliation at the time of the Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

which was hoped would end "The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

" in Northern Ireland.

According to R. F. Foster, the 1798 rebellion was "probably the most concentrated episode of violence in Irish history".

List of major engagements

See also

*Atlantic Revolutions

The Atlantic Revolutions (22 March 1765 – 4 December 1838) were numerous revolutions in the Atlantic World in the late 18th and early 19th century. Following the Age of Enlightenment, ideas critical of absolutist monarchies began to spread. A ...

* Battles during the 1798 rebellion

* Castle Hill convict rebellion

The Castle Hill convict rebellion was an 1804 convict rebellion in the Castle Hill area of Sydney, against the colonial authorities of the British colony of New South Wales. The rebellion culminated in a battle fought between convicts and the ...

in Sydney, Australia

* French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

* Irish issue in British politics

The issue of Ireland has been a major one in British politics, intermittently so for centuries. Britain's attempts to control and administer the island, or parts thereof, has had significant consequences for British politics, especially in the 19 ...

* List of Irish rebellions

This is a list of uprisings by Irish people against English and British claims of sovereignty over Ireland. These uprisings include attempted counter-revolutions and rebellions, though some can be described as either, depending upon perspective. ...

* Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, ...

* United Irish Uprising in Newfoundland

The United Irish Uprising in Newfoundland was a failed mutiny by Irish soldiers in the British garrison in St. John's, Newfoundland on 24 April 1800.

Background

In 1798, a failed rebellion against British rule in Ireland occurred. A larg ...

* List of monuments and memorials to the Irish Rebellion of 1798

A number of monuments and memorials dedicated to the Irish Rebellion of 1798 exist in Ireland and in other countries. Some of the monuments are in remembrance of specific battles or figures, whilst others are general war memorials.

Ireland

...

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * Aston, Nigel (2002) ''Christianity and Revolutionary Europe, 1750–1830'', Cambridge University Press . * Bartlett, Thomas, Kevin Dawson,Daire Keogh

Daire Kilian Keogh (born July 1964) is an academic historian and third-level educational leader, president of Dublin City University (DCU) since July 2020.

Keogh graduated in history, later taking a PhD while working part-time as a school tea ...

, ''Rebellion'', Dublin 1998

*

*

*