Raymond Robins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

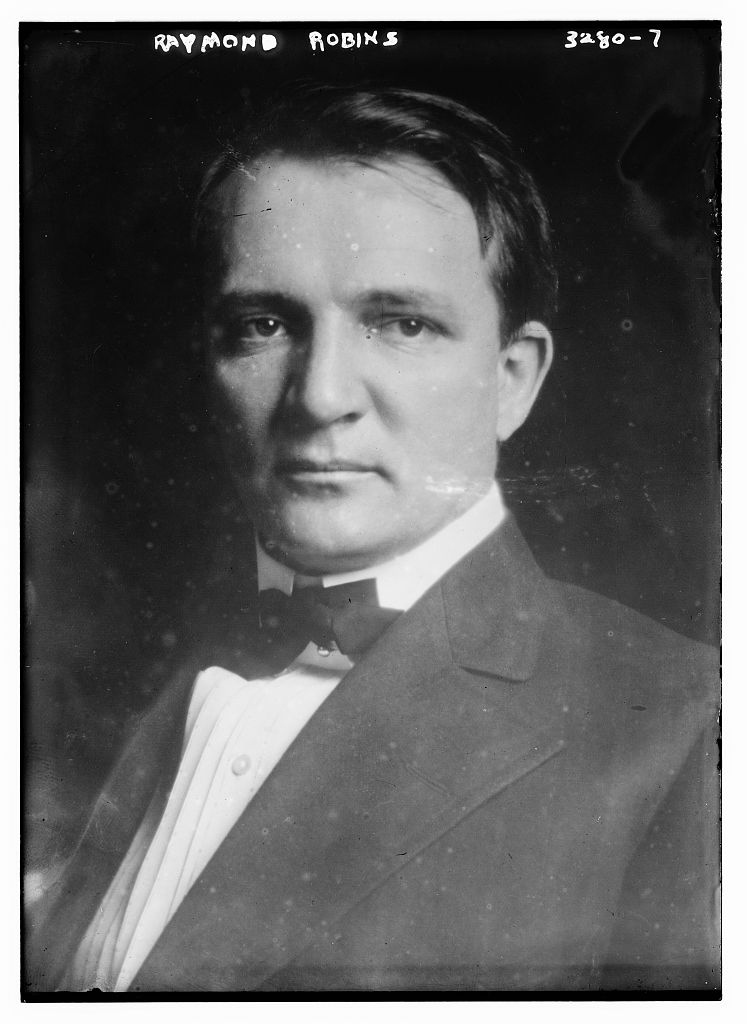

Raymond Robins (17 September 1873 – 26 September 1954) was an American

Raymond Robins (17 September 1873 – 26 September 1954) was an American

In 1905 Robins married Margaret Dreier, an independently wealthy labor activist who was president of the

In 1905 Robins married Margaret Dreier, an independently wealthy labor activist who was president of the

/ref> Robins served also as social service expert for the Men and Religion Forward Movement, in 1911–12, and made a world tour in its interests in 1913. He was leader of the National Christian Social Evangelistic campaign in 1915. He became identified with the

The Strange Case of Reynolds Rogers

/ref>

Raymond Robins

{{DEFAULTSORT:Robins, Raymond 1873 births 1954 deaths Economists from New York (state) Economists from Illinois American male non-fiction writers Illinois Progressives (1912) People with amnesia Members of the Chicago Board of Education

Raymond Robins (17 September 1873 – 26 September 1954) was an American

Raymond Robins (17 September 1873 – 26 September 1954) was an American economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

and writer. He was an advocate of organized labor and diplomatic relations between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

under the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s.

Biography

He was born on 17 September 1873 inStaten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

.

After financial troubles, his father left the children in care of his mother and left to do mining in Colorado. When his mother went into a mental asylum, his upbringing was left to relatives. He was educated privately. In the early 1890s, he worked as a coal miner in Tennessee and Colorado. After a bad legal experience in a land deal, he studied law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

at George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, preside ...

(then Columbian University) from where he graduated in 1896. He joined the Klondike gold rush in 1897, where he made some money, converted to Christianity, and became pastor for a Congregational church in Nome, Alaska

Nome (; ik, Sitŋasuaq, ) is a city in the Nome Census Area in the Unorganized Borough of Alaska, United States. The city is located on the southern Seward Peninsula coast on Norton Sound of the Bering Sea. It had a population of 3,699 recorded ...

. He moved to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1900. He engaged in social work

Social work is an academic discipline and practice-based profession concerned with meeting the basic needs of individuals, families, groups, communities, and society as a whole to enhance their individual and collective well-being. Social work ...

there 1902 to 1905, and was a member of the Chicago Board of Education

The Chicago Board of Education serves as the board of education (school board) for the Chicago Public Schools.

The board traces its origins to the Board of School Inspectors, created in 1837.

The board is currently appointed solely by the mayor ...

from 1906 to 1909.

In 1905 Robins married Margaret Dreier, an independently wealthy labor activist who was president of the

In 1905 Robins married Margaret Dreier, an independently wealthy labor activist who was president of the Women's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) (1903–1950) was a U.S. organization of both working class and more well-off women to support the efforts of women to organize labor unions and to eliminate sweatshop conditions. The WTUL played an important ...

.

In 1909, Robins attended a Labor Day

Labor Day is a federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday in September to honor and recognize the American labor movement and the works and contributions of laborers to the development and achievements of the United St ...

parade in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, after which he was interviewed by reporter and writer Marguerite Martyn

Marguerite Martyn (September 26, 1878 – April 17, 1948) was an American journalist and political cartoonist with the ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' in the early 20th century. She was noted as much for her published sketches as for her articles.

...

. He told her that "there are groups and groups of suffrage advocates, but when the women wage-earners become organized, you will see results from the cry of 'Votes for Women.'"Marguerite Martyn, "Agitator for Women's Suffrage and the Float in Labor Day Parade He Liked," ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch,'' September 10, 1909, Page 11/ref> Robins served also as social service expert for the Men and Religion Forward Movement, in 1911–12, and made a world tour in its interests in 1913. He was leader of the National Christian Social Evangelistic campaign in 1915. He became identified with the

Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

and served as chairman of the State Central Committee. In 1914, he was candidate for United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

for that party, and was temporary and permanent chairman of the Progressive National Convention in 1916.

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he was engaged in Y.M.C.A.

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

work and Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

work in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. In 1917, he headed the expedition for the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desi ...

to Russia, and worked unsuccessfully at establishing diplomatic relations between the United States and Russia, but some years later, in 1933, did manage to persuade Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to exchange ambassadors. On his return from the 1917 expedition, he presented an elaborate report on conditions in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, which occasioned much discussion on account of the report's alleged leaning toward the Soviet movement. Although not philosophically sympathetic with the outcome of the Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, he felt it was popular, and counter-revolutionary efforts were counter productive.

He died on 26 September 1954.

Family

The actress and writerElizabeth Robins

Elizabeth Robins (August 6, 1862 – May 8, 1952) was an actress, playwright, novelist, and suffragette. She also wrote as C. E. Raimond.

Early life

Elizabeth Robins, the first child of Charles Robins and Hannah Crow, was born in Louisville, ...

was his sister. In 1905, he married United States labor leader Margaret Dreier Robins

Margaret Dreier Robins (6 September 1868 – 21 February 1945) was an American labor leader and philanthropist.

Early life

She was born in Brooklyn, New York on 6 September 1868. Her parents, Theodor Dreier, a successful businessman, and Dorthea ...

.

Disappearance and amnesia

On 3 September 1932, Robins was traveling from the City Club inManhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, where he was supposed to meet with Herbert Hoover to discuss the urgent need for stronger enforcement of the Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

, a case Robins had been making over the past nine months on a 286-city tour. But Robins never showed up in the White House. After a two-month search, he was located in a boarding house in Whittier, North Carolina, under the name of Reynolds Rogers. Apparently because of his amnesia

Amnesia is a deficit in memory caused by brain damage or disease,Gazzaniga, M., Ivry, R., & Mangun, G. (2009) Cognitive Neuroscience: The biology of the mind. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. but it can also be caused temporarily by the use ...

, he did not recognize his wife, Margaret, until she had visited three times./ref>

See also

* Chinsegut Hill Manor HouseBibliography

*References

External links

* * * *Raymond Robins

{{DEFAULTSORT:Robins, Raymond 1873 births 1954 deaths Economists from New York (state) Economists from Illinois American male non-fiction writers Illinois Progressives (1912) People with amnesia Members of the Chicago Board of Education